Elevated serum cholesterol level is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease 1 and cholesterol lowering by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors or statins, has been shown to reduce cardiovascular events 2. The reduction in cardiovascular risks with statin therapy, whether for primary or secondary prevention, correlates almost linearly with the reduction in serum cholesterol levels 3. Indeed, for every 30 mg/dL decrease in low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), there is a concomitant 30% decrease in cardiovascular events 2. For patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome 4 or in patients with stable coronary artery disease 5, intensive lipid lowering therapy provides even greater clinical benefits, implying that the lower the LDL-C, the better is the outcome, especially for high-risk patients. Because most of the U.S. adult population with CHD has serum LDL-C levels between 135-145 mg/dL 6, in order to achieve an adult treatment panel (ATP) III/national cholesterol education panel (NCEP) guideline for LDL-C target goal of <100 mg/dL with an optional goal of <70 mg/dL, most high-risk patients with CHD will likely require at least a 40-50% reduction in LDL-C 2.

Depending upon the dose used, most statins can reduce serum cholesterol by 30-58% 7. This is compared to bile acid sequestrants or intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitors, which tend to lower serum cholesterol by only 15-18%. Thus, it is not surprising that statins have emerged as the principal cholesterol lowering therapy for patients at risk for cardiovascular disease. However, most statins, with the exception of the more potent statins such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, will require near maximum dosages in order to achieve a 40-50% LDL-C reduction. This is because the majority of statin's LDL-C lowering efficacy occurs at the starting dose with only a modest 4-6% further LDL-C reduction with doubling of the dose. However, titrating statins to higher doses in order to achieve LDL-C target goals increases their costs and potential side effects 8. It is because of these issues that most of the patients who begin statin therapy remain on their initial dose, and less than 30% of patients with CHD achieve a LDL-C target of <100 mg/dL 6, 9. Thus, there is a need for additional therapy to lower serum cholesterol levels, if treatment targets, especially for high-risk patients, are to be met.

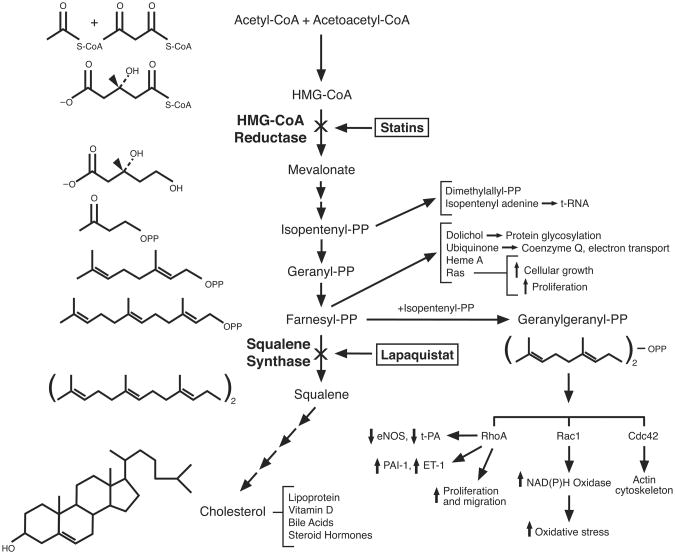

By blocking the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, statins inhibit the early rate-limiting step in cholesterol biosynthesis (Fig. 1). This leads to the upregulation of LDL receptors in the liver and increased clearance of serum cholesterol. However, by inhibiting cholesterol biosynthesis at such an early step, statins also decrease the production of mevalonate and isoprenoid intermediates such as isopentenylpyrophosphate, farnesylpyrophosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranylpyrophosphate (GGPP). Some of these isoprenoids serve as lipid attachments for signaling molecules belonging to the family of Ras and Rho GTPases, the inhibition of which, could mediate some of the non-cholesterol or pleiotropic effects of statins 10. However, these isoprenoid intermediates are also important precursors for signaling molecules that regulate protein synthesis (isopentenyl adenine), mitochondrial respiration (ubiquinone, coenzyme Q10), and glycosylation (dolichol). Thus, inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis by statins could be a double-edge sword. On the one hand, the inhibition of Rho GTPases may provide additional benefits beyond cholesterol reduction. Indeed, further cholesterol lowering using an intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitor, ezetimibe, failed to decrease atherosclerosis progression in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia compared to statins 11, suggesting that cholesterol lowering alone may not contribute to all of the clinical benefits observed with statin therapy. This issue will hopefully be addressed in terms of clinical outcomes in the on-going Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT), which will determine whether further cholesterol lowering by ezetimibe is beneficial compared to statin alone in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events 12. On the other hand, some of the unwanted side effects of statin therapy may be due to the inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis in skeletal muscle. Indeed, some in vitro studies suggest that myotoxicity induced by statins could be alleviated by the addition of isoprenoid intermediates, farnesol and geranylgeraniol 13. Because statin-induced myopathy and rhabdomyolysis are real safety concerns while statin pleiotropy remains a theoretical consideration, there is a need for therapeutic agents, which could decrease cholesterol biosynthesis without affecting isoprenoid metabolism. These newer therapies could also be used to determine whether there are any beneficial effects of statins beyond cholesterol lowering.

Figure 1. Cholesterol Biosynthesis.

Diagram of cholesterol biosynthesis pathway showing the chemical structure of some of the intermediates. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy 3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase by statins and inhibition of squalene synthase by lapaquistat are shown. Isoprenoids (isopentenyl-PP, gernayl-PP, farnesyl-PP, and geranylgeranyl-PP) are important modulators of various signaling pathways involving Rho GTPases (RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42). Note that squalene synthase is the first committed step towards cholesterol biosynthesis, which would not deplete cellular levels of isoprenoids. PP: pyrophosphate; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; t-PA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; ET-1: endothelin-1; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

Squalene synthase catalyzes the first committed step, which leads exclusively to the formation of cholesterol, by converting and dimerizing FFP to squalene (Fig. 1). In animal studies, squalene synthase inhibitors (SSIs) reduce hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis and upregulate LDL receptors, without depleting cellular levels of isoprenoids. Indeed, cellular levels of isoprenoids such as FPP are usually elevated due to higher HMG-CoA reductase activity from the lack of feedback inhibition, and increased backup of isoprenoid intermediates that leads to squalene. Furthermore, SSIs do not cause myotoxicity 13, and when co-administered with statins, decreased statin-induced myotoxicity 14. These initial findings provide the basis for the clinical development of SSIs as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to statins for patients who cannot achieve cholesterol target goals due to either statin intolerance, lack of sufficient statin potency, or both. However, it should be noted that most of the SSIs in clinical development have not progressed beyond clinical Phase I/II trials and many have been abandoned due to hepatotoxicity. Only one SSI, lapaquistat acetate, has progressed to Phase II/III clinical trials, and has accumulated sufficient efficacy and safety data for comparison with placebo and statins.

In this issue of Circulation (REF), Stein et al. summarizes the Phase II/III results from lapaquistat clinical program, which was halted due to safety concerns and lack of commercial viability (15). Although pooling of the data from 12 different clinical trials that range from 6 to 96 weeks in duration could lead to unforeseen bias and random errors, the analysis of the trials taken together consisted of more than 6,000 patients, most of whom were given the 50 and 100 mg daily dose of lapaquistat acetate, with or without statin therapy. Furthermore, for easier comparison, the efficacy for 3 monotherapy and 5 statin co-administration studies were reported separately. The trials included patients with heterozygous or homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, and all patients had LDL-C of >100 mg/dL and triglyceride (TG) of <400 mg/dL on entry. With the exception of one study where LDL-C was calculated, the LDL-C was directly measured using ultracentrifugation, which is important especially in patients with elevated TG where calculated LDL-C could be erroneous. In addition, patients were excluded, who have baseline alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels of >1.5 times upper limit of normal (ULN) or a creatinine phosphokinase (CK) levels of >3 times ULN. Overall completion rate was about 90% for both the placebo and lapaquistat acetate groups.

Compared to placebo, lapaquistat acetate 50 mg and 100 mg decreased LDL-C by 18% and 23%, respectively, at 12 weeks, and when co-administered with statins, decreased LDL-C by an additional 14% and 19%, respectively, at 24 weeks. Lapaquistat also significantly reduced non-HDL-C, TC, apolipoprotein B, VLDL-C, and TG when compared to placebo or to co-administration with statins. Interestingly, high-sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP), a nonspecific inflammatory marker, was also reduced by lapaquistat acetate in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that changes in serum cholesterol or TG levels may somehow modulate inflammatory status. The incidence of adverse events leading to withdrawal was fairly similar for all treatment groups with statin monotherapy group being slightly lower overall. This was somewhat surprising given that lapaquistat acetate was expected to cause less muscle-related side effects. However, the lack of difference in adverse events between the treatment groups could be simply due to the overall low rate of adverse events observed in the statin group, with or without lapaquistat acetate. Nevertheless, from an adverse event or muscle-related side effect perspective, there was no particular advantage of lapaquistate acetate compared to statin therapy.

Hepatotoxicity was the primary reason for halting the late-stage clinical development of lapaquistat 100 mg. In contrast, patients receiving lapaquistat 50 mg did not exhibit any signs of hepatotoxicity compared to patients receiving placebo. However, lapaquistat 50 mg was considered not commercially viable, when compared to existing therapies such as bile acid sequestrant and cholesterol absorption inhibitors, which could lower LDL-C to a comparable extent. The incidence of elevated transaminases (ALT and AST > 3xULN on 2 successive occasions) in patients taking lapaquistat 100 mg was between 2 to 3%, which was substantially higher compared to those taking placebo or statin monotherapy (<0.3%). In 2 patients, the elevation of ALT was accompanied by increases in total bilirubin levels, thereby fulfilling the FDA-defined “Hy's Law” for the likelihood of progression to hepatic failure 16. Thus, the decision to terminate further clinical development of lapaquistat acetate for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia was based upon the findings that compared to statin monotherapy, lapaquistat's LDL-C lowering efficacy was quite modest, the incidence of hepatotoxicity exceeded that of any commercially-available statins at their highest dose 8, and there was no observable reduction in the incidence of muscle-related side-effects.

It is likely that the failure of lapaquistat acetate will end further clinical development of SSIs for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. There are still several early-phase candidates in on-going clinical development, which target more distal pathways in cholesterol biosynthesis such as squalene monooxygenase, oxidosqualene cyclase, and lanosterol synthase 17. However, some of these agents, which inhibit oxidosqualene cyclase and lanosterol synthase, are associated with the development of cataracts. Thus, it remains to be determined whether any of these candidates will have efficacy and safety advantages over lapaquistat acetate, and more importantly, over statins. This begs the question as to whether there is a need for further development of inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis. Despite the inability to reach cholesterol target goals in some patients, the overwhelming clinical benefits and the overall safety profile of statins make it hard to justify using any other agents as first-line therapy for cholesterol reduction in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease. If adjunctive therapy is required to reach LDL-C target goals, perhaps the addition of fibrates or niacin, which have been shown to reduce cardiovascular events, could be used 18, 19. For patients who are intolerant of statin therapy because of potential side effects, adjunctive or monotherapy with bile acid sequestrants or intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitors may offer the best strategy for achieving targeted LDL-C goals. However, it is not known whether achieving further LDL-C reduction by non-statins, alone or in combination with statins, will result in further decrease in cardiovascular events. For example, is reaching LDL-C target goals by any means with non-statins more important in terms of cardiovascular risk reduction than how one achieves LDL-C target goals with statins? If not, then this would suggest that statin therapy is hard to beat when it comes to cardiovascular risk reduction. Whether this is due to cholesterol lowering, statin pleiotropy, or both remains to be determined. Unfortunately, because of safety concerns, the clinical development of lapaquistat acetate did not progress far enough to address this issue.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL052233).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sytkowski PA, Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB. Changes in risk factors and the decline in mortality from cardiovascular disease. The framingham heart study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1635–1641. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ. Implications of recent clinical trials for the national cholesterol education program adult treatment panel iii guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Illingworth DR. Management of hypercholesterolemia. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:23–42. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, Gotto AM, Greten H, Kastelein JJ, Shepherd J, Wenger NK. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1425–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson TA, Griffiths GG, Varas C, Gause D, Sung JC, Ballantyne CM. Impact of evidence-based “clinical judgment” on the number of american adults requiring lipid-lowering therapy based on updated NHANES III data. National health and nutrition examination survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1361–1369. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, Bays HE, McKenney JM, Miller E, Cain VA, Blasetto JW. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR* trial) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:152–160. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer HB., Jr Benefit-risk assessment of rosuvastatin 10 to 40 milligrams. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:23K–29K. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson TA, Laurora I, Chu H, Kafonek S. The lipid treatment assessment project (L-TAP): A multicenter survey to evaluate the percentages of dyslipidemic patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy and achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:459–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao JK, Laufs U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kastelein JJ, Akdim F, Stroes ES, Zwinderman AH, Bots ML, Stalenhoef AF, Visseren FL, Sijbrands EJ, Trip MD, Stein EA, Gaudet D, Duivenvoorden R, Veltri EP, Marais AD, de Groot E. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1431–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Califf RM, Lokhnygina Y, Cannon CP, Stepanavage ME, McCabe CH, Musliner TA, Pasternak RC, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, Harrington RA, Braunwald E. An update on the improved reduction of outcomes: Vytorin efficacy international trial (IMPROVE-IT) design. Am Heart J. 2010;159:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flint OP, Masters BA, Gregg RE, Durham SK. Inhibition of cholesterol synthesis by squalene synthase inhibitors does not induce myotoxicity in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;145:91–98. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimoto T, Ishikawa E, Anayama H, Hamajyo H, Nagai H, Hirakata M, Tozawa R. Protective effects of a squalene synthase inhibitor, lapaquistat acetate (TAK-475), on statin-induced myotoxicity in guinea pigs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;223:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein EA, Bays H, O'Brien D, Pedicano J, Piper E, Spezzi A. Lapaquistat Acetate: Development of a Squalene Synthase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2011:xx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.975284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reuben A. Hy's law. Hepatology. 2004;39:574–578. doi: 10.1002/hep.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlton-Menys V, Durrington PN. Human cholesterol metabolism and therapeutic molecules. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:27–42. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.035147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. Jama. 1975;231:360–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Fye CL, Anderson JW, Elam MB, Faas FH, Linares E, Schaefer EJ, Schectman G, Wilt TJ, Wittes J. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans affairs high-density lipoprotein cholesterol intervention trial study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:410–418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]