Abstract

Tissue-directed trafficking of dendritic cells (DCs) as natural adjuvants and/or direct vaccine carriers is highly attractive for the next generation of vaccines and immunotherapeutics. Since these types of studies would undoubtedly be first conducted using nonhuman primate models, we evaluated the ability of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) to induce gut-homing α4β7 expression on rhesus macaque plasmacytoid and myeloid DCs (pDCs and mDCs, respectively). Induction of α4β7 occurred in both a time-dependent and a dose-dependent manner with up to 8-fold increases for mDCs and 2-fold increases for pDCs compared to medium controls. ATRA treatment was also specific in inducing α4β7 expression, but not expression of another mucosal trafficking receptor, CCR9. Unexpectedly, upregulation of α4β7 was associated with a concomitant downregulation of CD62L, a marker of lymph node homing, indicating an overall shift in the trafficking repertoire. These same phenomena occurred with ATRA treatment of human and chimpanzee DCs, suggesting a conserved mechanism among primates. Collectively, these data serve as a first evaluation for ex vivo modification of primate DC homing patterns that could later be used in reinfusion studies for the purposes of immunotherapeutics or mucosa-directed vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

An ongoing research priority for multiple fields of immunology is to better understand the underlying mechanisms that regulate lymphocyte homing and retention. Although much is still unknown in this area of research, the role of retinoids in mucosal homing of lymphocytes has been identified by multiple groups. In a seminal study by Iwata et al. (1), it was shown that the vitamin A metabolite all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) produced by mucosal dendritic cells (DCs) is sufficient to induce the gut mucosa-homing molecules α4β7 and CCR9 on activated T cells and mediate gut homing and retention. Subsequent studies have confirmed this observation and linked α4β7 imprinting to accumulation of T cells in the gut mucosa (2, 3). Consistent with a pivotal role for ATRA in gut-homing imprinting, it was shown more recently that ATRA is also necessary for the induction of gut-homing receptors on B cells (3, 4). Collectively, these findings provided a mechanistic basis for older observations that vitamin A-deficient rats exhibit impaired migration of lymphocytes to the intestinal mucosa (5, 6). In an experimental biology setting, ATRA has also been applied as an effective adjuvant for expansion of antigen-specific mucosal CD8+ T cells, presumably by increasing dendritic cell presentation and/or trafficking to those tissues (7, 8).

In peripheral blood of primates, two major types of DCs predominate, myeloid DCs (mDCs), characterized by expression of the cell surface integrin, CD11c, and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) that express high levels of the interleukin 3 receptor alpha subunit (IL-3Rα) chain, CD123 (9–13). In addition, both subsets of DCs express high levels of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules and are devoid of common lineage (Lin) markers expressed on T cells (CD3), monocytes (CD14), B cells (CD20), and NK cells (CD16 and CD56). Although in general DCs are presumed to develop in the bone marrow and then egress to other tissues, the mechanisms regulating DC trafficking are not completely understood. Evidence from mouse studies indicates that retinoids are involved in the in vivo process of gut imprinting of DCs and that this process typically occurs in the bone marrow (14). Conversely, blocking retinoid receptors decreases the induction of gut homing by mucosal DCs and pharmacological inhibition of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) inhibits DC imprinting of gut tropism (1). Since access to tissues in humans is often limited, monitoring trafficking of DCs is ideal for nonhuman primate (NHP) models. To this end, we and others have previously shown that DCs traffic between bone marrow and blood and even to the gut mucosa, dependent on α4β7 (12, 13, 15–18). We further showed that these processes are significantly altered by viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). However, the mechanisms involved remain unclear and whether or not retinoids could be used experimentally to site-direct DC trafficking in humans and other primates is unknown. As an initial step to later in vivo studies, we sought to determine the efficacy of ATRA-dependent imprinting on macaque DCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) of Indian genetic background were analyzed. All macaques were free of simian immunodeficiency virus, simian retrovirus type D, simian T cell-lymphotrophic virus type 1, and herpes B virus and were housed at the New England Primate Research Center (NEPRC) and maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animals of the Harvard Medical School and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Fresh chimpanzee blood samples were obtained from captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (YNPRC), Emory University (supported by NIH grant RR000165). These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University. The NEPRC and YNPRC are fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Human (Homo sapiens) samples were collected from normal volunteer donors.

Cell processing.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from EDTA-treated blood by density gradient centrifugation over lymphocyte separation medium (LSM) (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and contaminating red blood cells were lysed using a hypotonic ammonium chloride solution. After isolation, all cells were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for subsequent assays or frozen in a 90% FCS-10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution.

Polychromatic flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry staining of mononuclear cells was carried out for cell surface molecules according to standard protocols (19). A vital stain (Live/Dead) and isotype-matched and/or fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls were included in all assays. All acquisitions were made on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). All antibodies were tested for cross-reactivity and were purchased from BD Biosciences unless otherwise indicated. Panels consisted of monoclonal antibodies to the following surface molecules: α4β7 (clone A4B7, allophycocyanin [APC] conjugate; NIH NHP Reagent Resource), CCR9 (clone 112509, fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] conjugate; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN), CD3 (clone SP34-2, APC-Cy7 conjugate), CD11c (clone S-HCL-3, APC or phycoerythrin [PE] conjugates), CD14 (clone TUK4, Alexa Fluor 700 conjugate; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), CD20 (clone L27, peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCp]-Cy5.5 conjugate), CD62L (clone SK11, PE conjugate), CD123 (clone 7G3, PE-Cy7 conjugate), and HLA-DR (clone Immu-357, PE-Texas Red conjugate; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA).

Statistical analyses.

All graphical and statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Wilcoxon matched-pair tests were used where indicated; P values of <0.05 were assumed to be significant.

Cell culture.

For each condition, PBMCs were suspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 PBMCs/ml in medium consisting of RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY) with 10% FCS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and supplemented with l-glutamine (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA), penicillin-streptomycin (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA), and 1 M HEPES buffer (Mediatech Inc.). All-trans-retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added for final concentrations of 0 (R10 control), 25, 100, and 200 nM, chosen based on previous observations (1, 3, 20). All cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 for up to 72 h as indicated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of DC subsets in primate blood.

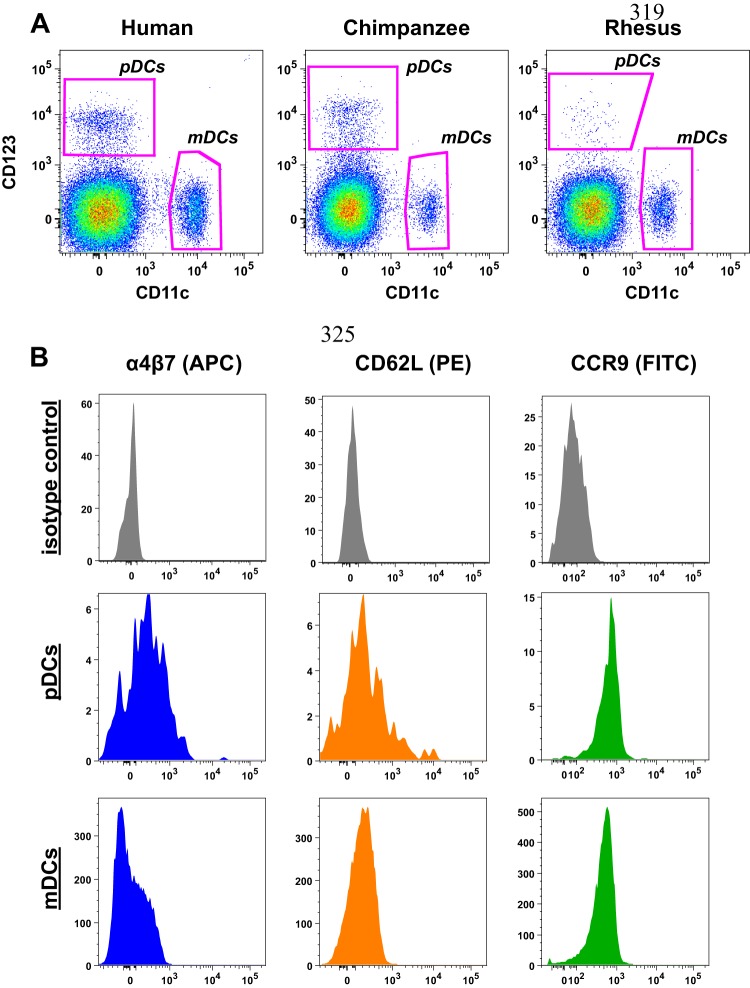

pDCs and mDCs were identified by mutually exclusive expression of CD123 and CD11c, respectively (Fig. 1A), among live rhesus macaque mononuclear cells, and were devoid of CD3, CD14, and CD20 but positive for HLA-DR. We have previously established this as the most effective gating strategy to identify DCs in rhesus macaques, and similar strategies are employed to identify pDCs and mDCs in humans and chimpanzees (Fig. 1) (9, 12, 13, 18, 21). Next, we measured basal expression of homing molecules on rhesus macaque DCs (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, expression of α4β7 was 10-fold greater on pDCs than on mDCs, with median fluorescence intensities of 210 and 20, respectively. By comparison, expression levels of CCR9 and CD62L, a marker of lymph node homing, were highly similar between the two DC subtypes (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2). These data could suggest that pDCs have a higher basal level of potential trafficking to the gut mucosa than do mDCs.

Fig 1.

Identification of primate dendritic cells among blood mononuclear cells. (A) Representative gating of CD123+ pDCs and CD11c+ mDCs identified among CD3− CD14− CD20− HLA-DR+ live mononuclear cells from rhesus macaques, humans, and chimpanzees. (B) Representative histograms demonstrating differences in expression of α4β7, CD62L, and CCR9 on pDCs compared to mDCs from rhesus macaques.

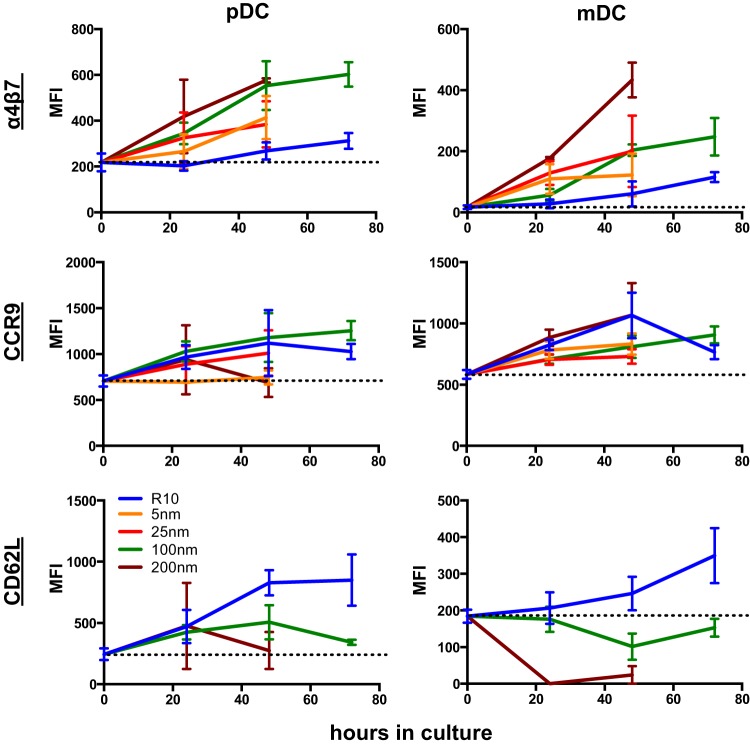

Fig 2.

ATRA alters homing molecule expression on rhesus macaque DCs in a dose-dependent manner. α4β7, CD62L, and CCR9 were measured on rhesus macaque pDCs and mDCs from parallel cultures with added exogenous ATRA in various concentrations and collected at multiple time points. Error bars represent means ± standard errors of the means of 6 macaques/independent experiments. Dashed lines indicate mean expression at time zero. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

ATRA treatment induces α4β7 expression on rhesus macaque DCs in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

Since DCs are prime targets for next-generation vaccines and immunotherapies, we wanted to evaluate methods to regulate DC mucosal homing. To do so, we measured the effects of culturing cells with increasing concentrations of ATRA over a 72-hour period on DC expression of α4β7, CCR9, and CD62L (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, even in control cultures of medium alone (R10), both DC subsets exhibited modest upregulation of all three homing molecules. This could suggest (i) some artificial culture-induced change or could suggest that (ii) in the absence of certain in vivo stimuli, the cells will naturally upregulate these markers as they mature. However, ATRA treatment induced a dose-dependent increase in α4β7 on both pDCs and mDCs, with the highest concentration, 200 nM, inducing the greatest increase in α4β7 expression over R10—8-fold for mDCs and 2-fold for pDCs. Upregulated expression of α4β7 was also time dependent, with expression increasing through the entire 72 h of culture, after which time cell viability began to decline (data not shown). α4β7 upregulation was also generalized for the bulk DC populations, rather than affecting only a subset (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). CCR9, which also generally increased over time in culture, was not affected by ATRA treatment. These data suggested that ATRA treatment was specific for imprinting of α4β7. Surprisingly, ATRA treatment also suppressed expression of the lymph node homing marker CD62L, with a 3-fold decrease in expression on pDCs and a 10-fold decrease on mDCs when comparing the 200 nM ATRA cultures to R10. These data are well in line with previous observations showing ATRA-induced α4β7 expression on monocyte-derived DCs (20) but are likely the first demonstration for primary primate DCs and the first to show suppression of CD62L.

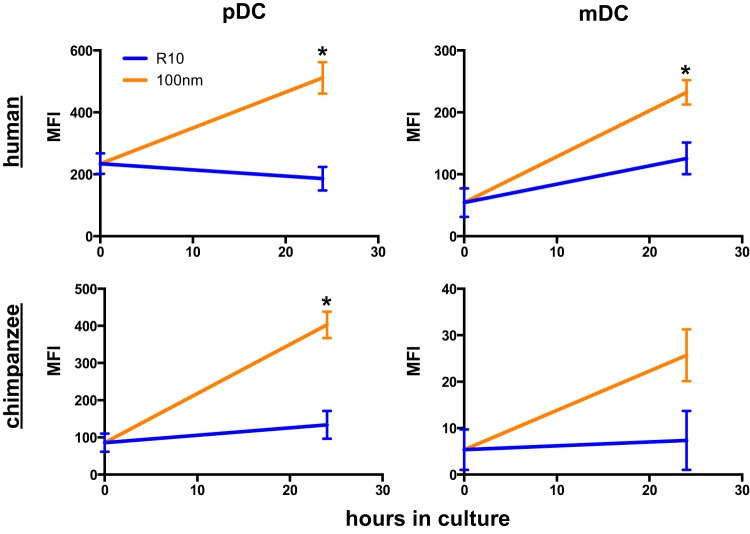

ATRA induces α4β7 expression on human and chimpanzee DCs.

Since preclinical use of gut-imprinted DCs in macaque models could also eventually be of interest in human therapeutics, we next wanted to evaluate whether ATRA treatment of human DCs would yield similar results. Human DCs were gated as shown in Fig. 1A and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. An approximately 2.5-fold increase in α4β7 expression was observed on both pDCs and mDCs when comparing the R10 control cultures to those with 100 nM ATRA (Fig. 3). These data indicated that a similar induction of α4β7 could be induced in human DCs. Finally, we repeated these experiments using PBMCs from normal chimpanzees to determine if the effects of ATRA treatment were generalized for primate species. As expected, 100 nM ATRA culture induced 4-fold increases in α4β7 expression on mDCs and pDCs from chimpanzees (Fig. 3). Collectively, these data suggest that ATRA-induced expression of α4β7 on DCs is conserved among primate species.

Fig 3.

ATRA induces upregulation of α4β7 on human and chimpanzee DCs. Mononuclear cells from human and chimpanzee blood samples were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of 100 nM ATRA, and expression of α4β7 was measured on pDCs and mDCs. *, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pair test; only significant values are shown. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

The data presented here describe a phenomenon whereby exogenous ATRA can specifically induce α4β7 expression while suppressing CD62L expression on both pDCs and mDCs. With a burgeoning interest in DC-based vaccines and immunotherapeutics, the possibility of site-directing delivery of such modalities is highly appealing. Although these experiments demonstrate only in vitro effects, they are highly significant since this is the first evidence that DC homing repertoires can be “directed,” and also “redirected” as evidenced by downregulation of CD62L. Furthermore, these data indicate that ATRA-induced α4β7 expression is conserved among three primate species, suggesting that this methodology could eventually be applied to clinical trials. Future studies will be necessary to better understand the mechanisms of homing molecule expression in response to ATRA treatment and to assess effects on functional capacity—retinoids can modulate dendritic cell stimulatory capacity (22). Thus, additional in vitro work is likely required before assessing in vivo efficiency of experimentally induced homing. Such studies will undoubtedly utilize more costly, labor-intensive NHP model studies, underscoring the importance of the conservation of this mechanism among species. Collectively, these assessments are an important first step in developing new technologies for tissue-directed vaccines and immunotherapeutics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful thanks are expressed to Jacqueline Gillis and Michelle Connole for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by an amfAR research grant, grant number 108547-53-RGRL (to R.K.R.), and NIH NEPRC base grant P51 OD011103.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00419-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. 2004. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity 21:527–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Wurbel MA, Malissen B, Marquez G, Agace W. 2003. Selective generation of gut tropic T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): requirement for GALT dendritic cells and adjuvant. J. Exp. Med. 198:963–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mora JR, Bono MR, Manjunath N, Weninger W, Cavanagh LL, Rosemblatt M, Von Andrian UH. 2003. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer's patch dendritic cells. Nature 424:88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K, Jang MH, Yang BG, Jung YJ, Nishiyama M, Sato S, Tsujimura T, Yamamoto M, Yokota Y, Kiyono H, Miyasaka M, Ishii KJ, Akira S. 2008. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat. Immunol. 9:769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjersing JL, Telemo E, Dahlgren U, Hanson LA. 2002. Loss of ileal IgA+ plasma cells and of CD4+ lymphocytes in ileal Peyer's patches of vitamin A deficient rats. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott MR, Mark DA, Befus AD, Baliga BS, Suskind RM, Bienenstock J. 1982. Impaired intestinal localization of mesenteric lymphoblasts associated with vitamin A deficiency and protein-calorie malnutrition. Immunology 45:1–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePaolo RW, Abadie V, Tang F, Fehlner-Peach H, Hall JA, Wang W, Marietta EV, Kasarda DD, Waldmann TA, Murray JA, Semrad C, Kupfer SS, Belkaid Y, Guandalini S, Jabri B. 2011. Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature 471:220–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan X, Sande JL, Pufnock JS, Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. 2011. Retinoic acid as a vaccine adjuvant enhances CD8+ T cell response and mucosal protection from viral challenge. J. Virol. 85:8316–8327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. 2004. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat. Immunol. 5:1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellman I, Steinman RM. 2001. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell 106:255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messaoudi I, Estep R, Robinson B, Wong SW. 2011. Nonhuman primate models of human immunology. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14:261–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves RK, Fultz PN. 2008. Characterization of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in bone marrow of pig-tailed macaques. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves RK, Fultz PN. 2007. Disparate effects of acute and chronic infection with SIVmac239 or SHIV-89.6P on macaque plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Virology 365:356–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng T, Cong Y, Qin H, Benveniste EN, Elson CO. 2010. Generation of mucosal dendritic cells from bone marrow reveals a critical role of retinoic acid. J. Immunol. 185:5915–5925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barratt-Boyes SM, Wijewardana V, Brown KN. 2010. In acute pathogenic SIV infection plasmacytoid dendritic cells are depleted from blood and lymph nodes despite mobilization. J. Med. Primatol. 39:235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown KN, Trichel A, Barratt-Boyes SM. 2007. Parallel loss of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells from blood and lymphoid tissue in simian AIDS. J. Immunol. 178:6958–6967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown KN, Wijewardana V, Liu X, Barratt-Boyes SM. 2009. Rapid influx and death of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lymph nodes mediate depletion in acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000413. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Wong FE, Kang G, Li Q, Johnson RP. 2012. SIV infection induces accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the gut mucosa. J. Infect. Dis. 206:1462–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Johnson RP. 2010. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection induces expansion of alpha4beta7+ and cytotoxic CD56+ NK cells. J. Virol. 84:8959–8963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardo D, Mann ER, Al-Hassi HO, English NR, Man R, Lee GH, Ronde E, Landy J, Peake ST, Hart AL, Knight SC. 2013. Lost therapeutic potential of monocyte-derived DC through lost tissue homing; stable restoration of gut specificity with retinoic acid. Clin. Exp. Immunol. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1111/cei.12118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Fultz PN, Johnson RP. 2011. Potential confusion of contaminating CD16+ myeloid DCs with anergic CD16+ NK cells in chimpanzees. Eur. J. Immunol. 41:1070–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedford PA, Knight SC. 1989. The effect of retinoids on dendritic cell function. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 75:481–486 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.