Abstract

Myotubularin (MTM1) and amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) are two proteins mutated in different forms of centronuclear myopathy, but the functional and pathological relationship between these two proteins was unknown. Here, we identified MTM1 as a novel binding partner of BIN1, both in vitro and endogenously in skeletal muscle. Moreover, MTM1 enhances BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation, depending on binding and phosphoinositide phosphatase activity. BIN1 patient mutations induce a conformational change in BIN1 and alter its binding and regulation by MTM1. In conclusion, we identified the first molecular and functional link between MTM1 and BIN1, supporting a common pathological mechanism in different forms of centronuclear myopathy.

Keywords: amphiphysin, BIN1, centronuclear myopathy, myotubular myopathy, MTM1, myotubularin

INTRODUCTION

Centronuclear myopathies (CNM) define a heterogeneous group of inherited muscular disorders characterized by muscle weakness, fibre atrophy and abnormal localization of nuclei and other organelles [1]. Mutations in the phosphoinositides phosphatase myotubularin (MTM1) lead to a significant decrease of the protein level [2] and cause the X-linked form of CNM, also called myotubular myopathy [3]. MTM1 dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) and PtdIns(3,5)P2 and produce PtdIns5P [4–6] and both phosphatase-dependent and independent functions of MTM1 are necessary for normal skeletal muscle function [7]. Mutations in amphiphysin 2 (AMPH2 or BIN1) cause an autosomal recessive form of CNM [8]. BIN1 is a protein belonging to the BAR (BIN/Amphiphysin/Rvs) domain protein family and involved in both curvature sensing and membrane bending [9, 10]. In addition to its N-BAR domain, BIN1 has a SH3 domain that binds proline-rich domain containing proteins. The muscle-specific isoform (isoform 8) contains an additional PI motif composed of a stretch of polybasic residues that binds phosphoinositides as PtdIns4,5P2 and promotes membrane tubulation [11].

In this study, we investigated the potential functional link between MTM1 and BIN1 to identify a common pathological mechanism underlying CNM.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

MTM1 and BIN1 interact in skeletal muscle

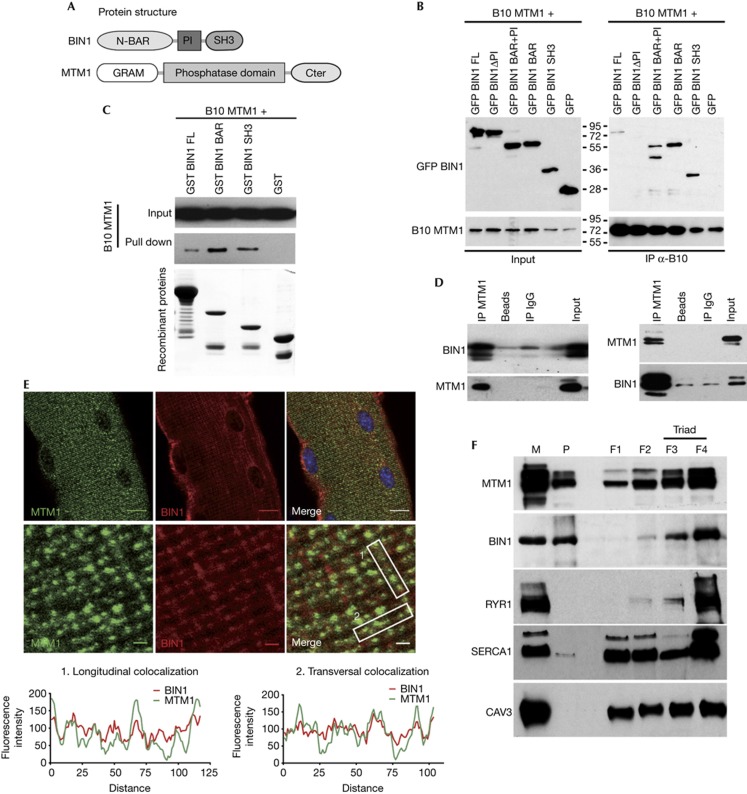

To address the potential molecular interaction between MTM1 and BIN1, several constructs expressing tagged BIN1 domains and full-length (FL) protein (Fig 1A) were used. GFP-tagged BAR+PI, BAR, SH3 and BIN1 FL co-immunoprecipitated with B10-MTM1 (Fig 1B). Similar results were obtained when the co-immunoprecipitation was performed in the reverse direction (supplementary Fig S1 online). Moreover, GST-tagged BIN1 full length, BAR and SH3, produced in bacteria, were able to pull down in vitro-translated B10-MTM1 (Fig 1C), suggesting that MTM1 interacts directly with BIN1. The stronger interaction observed after co-immunoprecipitation and pull-down with BAR and SH3 domains compared with BIN1 FL (Fig 1B,C; supplementary Fig S1 online) suggested MTM1 interaction depends on BIN1 conformation. Indeed, it has been proposed that BIN1 has a dual open/closed conformation controlled by the interaction of the SH3 domain with the BAR+PI domain of BIN1 and regulating its interaction with proteins like dynamin 2 [12]. No interaction of B10-MTM1 with GFP-BIN1ΔPI was detected after co-immunoprecipitation (Fig 1B; supplementary Fig S1 online). Because of its localization between the SH3 and the BAR domains, the PI motif could modulate the relative position of these two domains within the BIN1 protein, and by this way control MTM1 interaction. In addition, as BIN1 undergoes complex tissue-specific splicing events and the PI motif is mainly found in skeletal muscle isoforms of BIN1 [13, 14], we propose that the precise regulation of BIN1 conformation and its membrane tubulation properties is particularly important in this tissue.

Figure 1.

MTM1 and BIN1 interact in vitro and in vivo and partially colocalize in skeletal muscle. (A) Representation of domains of BIN1 (isoform 8) and MTM1 proteins. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-B10 antibodies on lysates from COS-1 cells expressing B10-MTM1 and GFP-fused BIN1 domains. Top panel: immunoblot hybridized with anti-GFP antibodies. Bottom panel: immunoblot hybridized with anti-MTM1 antibodies. (C) MTM1 and BIN1 interact directly. GST (negative control), GST-BIN1, GST-BAR and GST-SH3 recombinant proteins were used to pull down B10-MTM1 produced by in vitro translation. Top panels: immunoblot hybridized with anti-B10 antibody. Bottom panel: Coomassie blue staining showing recombinant proteins used for the pull-down. (D) BIN1 and MTM1 interact in vivo. Co-immunoprecipitation assays on membrane-enriched fractions from mouse muscle homogenates using anti-MTM1 (left panel) or anti-BIN1 (right panel) antibodies. Immunoblots were hybridized with anti-BIN1 or anti-MTM1 antibodies. Non-conjugated beads and IgG were used as controls. (E) MTM1 and BIN1 partially localize on the same subcellular structure in isolated muscle fibres. Muscle fibres isolated from 5-week-old wild-type mouse were stained with anti-MTM1 and pan-isoform anti-BIN1 antibodies. Confocal planes in the middle of fibres. Scale bar, 10 μm (top panel), 1 μm (middle panel). Quantitative measurement of BIN1 and MTM1 fluorescence intensity (bottom panel). (F) MTM1 and BIN1 are both enriched at the triads. Subcellular fractionation of membranes from rabbit skeletal muscle on the basis of a discontinuous sucrose gradient, as in Amoasii et al [7]. Longitudinal sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes were enriched in fractions F1 and F2 (SERCA1), and triad membranes were enriched in fractions F3 and F4 (RYR1). Caveolin-3 was used as a sarcolemmal marker. BAR, BIN/Amphiphysin/Rvs; BIN1, amphiphysin 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; M, microsome; MTM1, myotubularin; P, pellet.

To test the existence of this interaction at the endogenous level, MTM1 was immunoprecipitated from muscle protein extracts. Several BIN1 specific bands were detected by western blot (Fig 1D), corresponding to the BIN1 isoforms already described in muscle [8]. Moreover, a doublet corresponding to muscle MTM1 (70 kDa; [15]) was also detected after BIN1 immunoprecipitation (Fig 1D), confirming that MTM1 and BIN1 interact at the endogenous level in the skeletal muscle. Immunofluorescence experiments performed on isolated murine muscle fibres showed that MTM1 and BIN1 partially colocalized on the same structures (Fig 1E). Partial colocalization in isolated muscle fibres of both proteins with triad markers RYR1 and DHPRα, as previously shown in murine muscle sections [13, 14, 16], and no extensive colocalization of BIN1 with sarcomeric actin and the Z-line marker α-actinin, point to a localization of BIN1 and MTM1 mainly at triads next to the Z-line, in the I-band of the sarcomere (supplementary Fig S2 online). Moreover, after subcellular fractionation of rabbit skeletal muscle, MTM1 and BIN1 were both enriched in RYR1 positive fractions (3 and 4) representing junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum and triads (Fig 1F). Overall, we propose that a fraction of MTM1 and BIN1 is in complex at the triad. Triads are structures composed by sarcoplasmic reticulum cisternae connected to a plasma membrane invagination, the T-tubule (supplementary Fig S2 online); they are involved in the excitation–contraction coupling in muscle cells. BIN1, on the basis of its role in membrane tubulation, was proposed to participate to T-tubule formation [11, 17]. In addition to a role at the triad, BIN1 could have a pleiotropic role in the organization/functioning of the sarcomere, as it was proposed to mediate interaction with proteins of the structure of the sarcomere, actin and myosin [18].

MTM1 enhances BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation

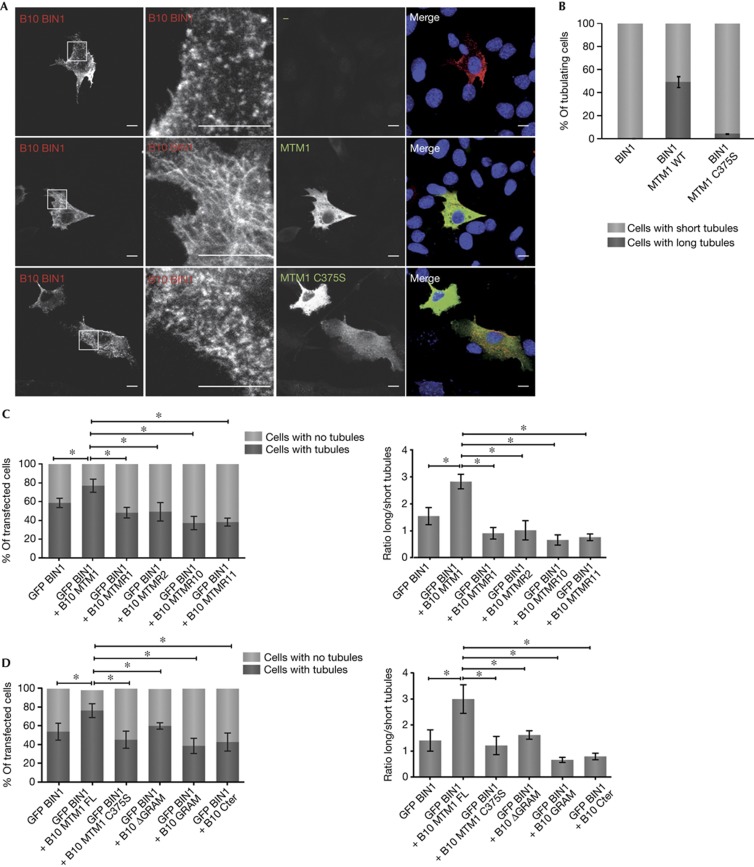

As BIN1 has been shown to trigger membrane tubulation in cells [8, 11], the impact of MTM1 on this function was tested in C2C12 myoblasts. In these cells, B10-BIN1 expression induced short membrane tubules (Fig 2A,B; supplementary Fig S3B online). Ectopic co-expression of MTM1 altered BIN1 tubulation pattern leading to longer and more reticulated tubules in about 50% of tubule-positive cells (Fig 2A,B; supplementary Fig S3A,B online). This impact was confirmed in COS-1 cells, in which co-expression of B10-MTM1 with GFP-BIN1 increased the number of tubulating cells and the length of the tubules (Fig 2C,D; supplementary Figs S4A and S5A online). These data suggest that MTM1 enhances the membrane tubulation function of BIN1.

Figure 2.

Impact of MTM1 on BIN1 membrane tubulation. (A) Ectopic expression of MTM1 enhances BIN1 membrane tubulation. C2C12 cells expressing B10-BIN1 alone (top panel) or with catalytically inactive p.C375S MTM1 (bottom panel) display short membrane tubules, although co-expression with wild-type MTM1 promotes longer membrane tubules (middle panel). Immunofluorescence was performed using anti-B10 and anti-MTM1 antibodies. Images represent confocal z-stack projections. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of C2C12 cells presenting short tubules versus cells presenting long tubules under different conditions. About 100 cells/experiment were counted in three independent experiments. (C) Quantification of COS-1 cells presenting tubules versus cells presenting no long tubules (left panel), and ratio long tubules/short tubules in cells (right panel) depending on BIN1 co-expression with different myotubularins. (D) Quantification of COS-1 cells presenting tubules versus cells presenting no tubules (left panel), and ratio long tubules/short tubules in cells (right panel) depending on BIN1 co-expression with different MTM1 domains. For (C) and (D), about 200 transfected cells (with/without tubules) and 20–30 tubules/cell in about 90 transfected cells (ratio long tubules/short tubules) were counted. The statistical significance was calculated on the basis of number of cells from one of two independent experiments; the second set looked similar. *P<0.05, considered significant. BIN1, amphiphysin 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MTM1, myotubularin; WT, wild type.

Catalytically inactive MTM1 mutants were then used to determine the importance of the phosphatase activity in the regulation of BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation. In contrast to wild-type MTM1, ectopic expression in C2C12 of p.C375S, p.D278A and p.R421Q MTM1 inactive mutants did not enhance BIN1 tubulation (Fig 2A,B; supplementary Table SI online). The majority of these mutants pulled down with the BAR domain of BIN1 (supplementary Fig S3C), suggesting that they fail to enhance BIN1 membrane tubulation due to a lack of catalytic activity rather than a decreased binding. The p.C375S MTM1 mutant was not able to pull down with GST-BIN1 BAR, contrary to other inactive MTM1 mutants tested (supplementary Fig S3C online). This suggests that the p.C375S mutation affects the interaction, for example through the regulation of MTM1 structure or oligomerization. The inability of the p.C375S MTM1 mutant to fully rescue all Mtm1-null mice phenotypes, as previously shown [7], could then be due either to lack of enzymatic activity or to decreased BIN1 binding.

To further study the regulation of BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation, MTM1 homologues that are catalytically active (MTMR1 and MTMR2) or inactive (MTMR10 and MTMR11) were then used. Ectopic expression of these MTM1 homologues in COS-1 cells also failed to enhance BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation (Fig 2C; supplementary Fig S4A; supplementary Table SI online), indicating that the catalytic activity of MTMR1 and MTMR2, that is similar to MTM1, is not sufficient. MTM1 homologues did not pull down with GST-BIN1 (supplementary Fig S4B online), suggesting that the binding of MTM1 to BIN1 is also important for the regulation of membrane tubulation. However, a difference in phosphoinositides sub-pools dephosphorylated by MTMR1/2 and MTM1 cannot be excluded.

To clarify the importance of binding, we mapped the binding domain of MTM1 to BIN1. GST-tagged MTM1 full length and ΔGRAM were able to pull down B10-BIN1, whereas binding of B10-BIN1 to GST-MTM1GRAM and GST-MTM1Cter was very weak (supplementary Fig S5B online), suggesting that BIN1 interacts with the phosphatase domain, between the GRAM and Cter domains (Fig 1A). The MTM1ΔGRAM protein has impaired catalytic activity (supplementary Fig S5C online), and does not significantly enhance BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation (Fig 2D; supplementary Fig S5A; supplementary Table SI online). Taken together, these results sustain the conclusion that MTM1 specifically enhances BIN1 membrane tubulation and that the enzymatic activity and to some extent the binding are needed for this role. MTM1 might therefore regulate BIN1-mediated membrane curvature at the triad via regulation of phosphoinositide levels or protein binding, but further analysis will be needed to address their actual role in triad formation and maintenance.

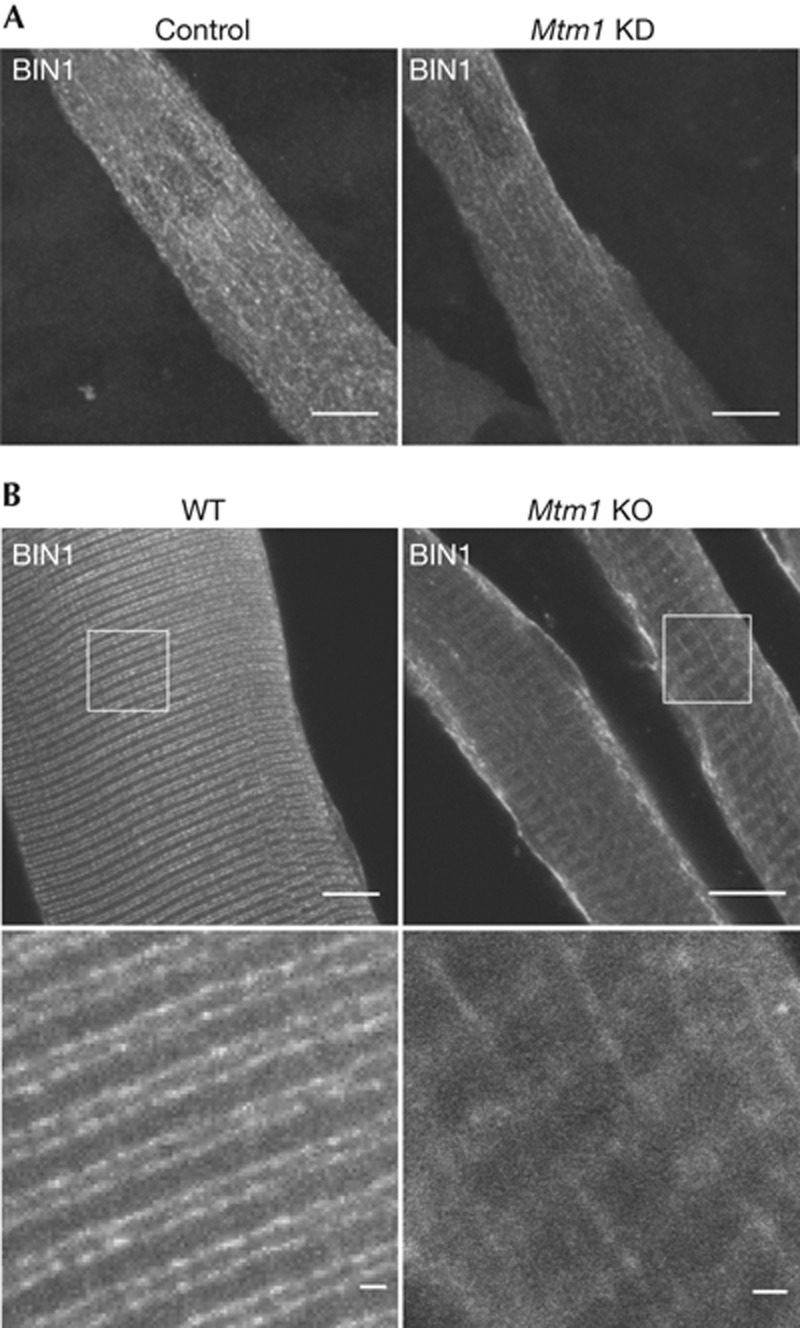

MTM1 regulates BIN1-membrane structures in muscle

It was previously reported that T-tubules are altered in the mature muscles from Zebrafish, mouse and human with impaired or mutated MTM1 [14, 19, 20]. We took advantage of C2C12 myotubes to follow BIN1 localization in normal and MTM1-depleted cells. BIN1-positive tubules were longitudinally oriented in normal cells as previously described [11, 21], but also in Mtm1 knockdown myotubes (Fig 3A), supporting that endogenous BIN1 tubules in immature muscle cells do not depend on MTM1. Conversely, both longitudinal and transversal pattern of BIN1 were observed in isolated muscle fibres from 5-week-old Mtm1 knockout mice whereas BIN1 was present only as a transversal doublet at the triads in wild-type fibres (Fig 3B). These findings point to a role of MTM1 for the transversal positioning of BIN1-positive membrane structures during maturation.

Figure 3.

MTM1 depletion impairs BIN1 tubule positioning in differentiated muscle fibres. (A) Knockdown of Mtm1 did not alter BIN1 membrane tubulation in cultured myotubes. Immunofluorescence using anti-BIN1 antibodies was performed on C2C12 myotubes, wild type or knocked down for MTM1. Images represent confocal z-stack projections. (B) Orientation of BIN1-positive structures is altered in Mtm1 KO isolated muscle fibres compared with WT fibres. Immunofluorescence using anti-BIN1 antibodies was performed on muscle fibres isolated from 5-week-old wild type and Mtm1 KO mice. Mtm1 KO fibres are atrophic. Confocal planes in the middle of fibres. Scale bars, 10 μm. BIN1, amphiphysin 2; KO, knockout; MTM1, myotubularin; WT, wild type.

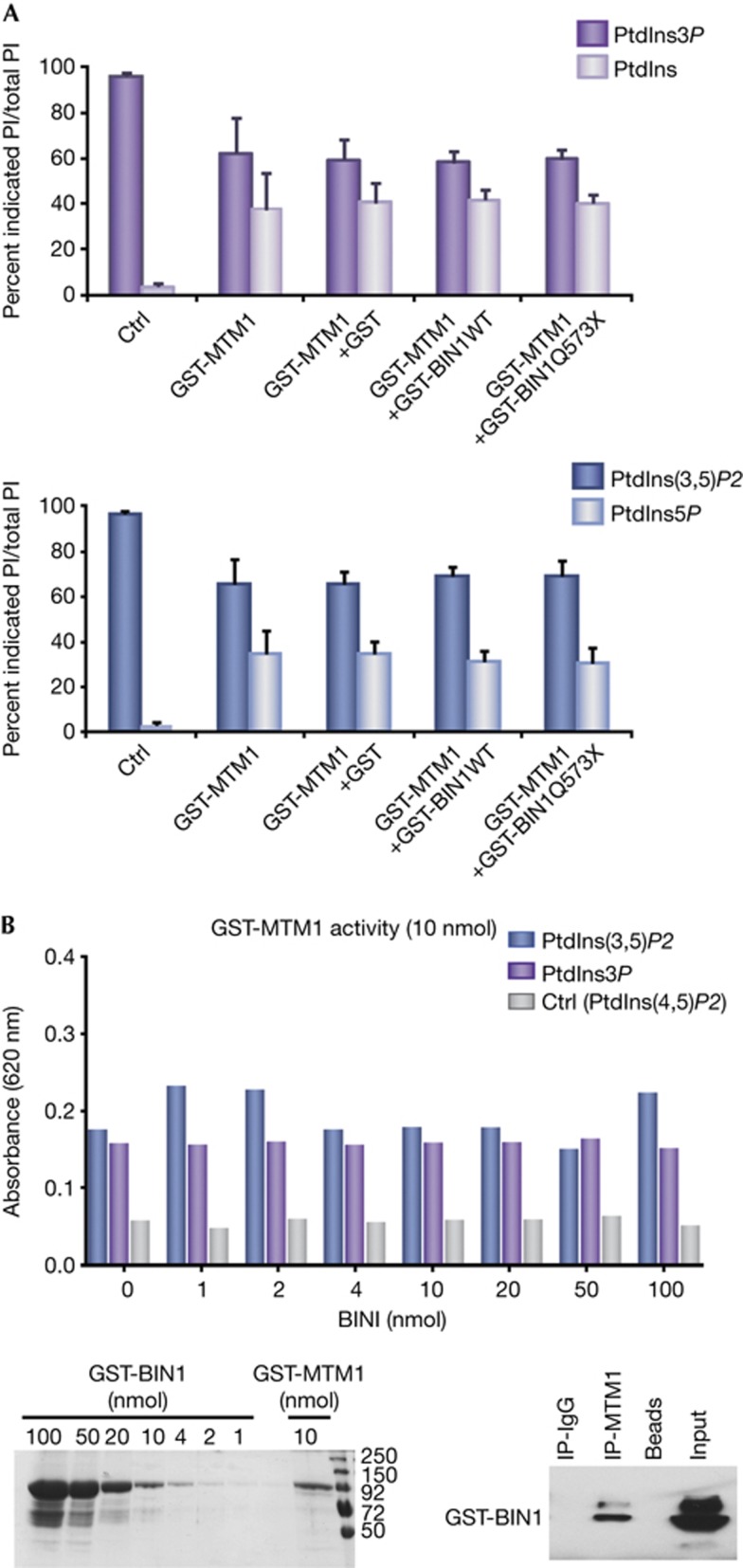

BIN1 does not regulate MTM1 phosphatase activity

To investigate if BIN1 impacts on MTM1 function, the phosphatase activity of MTM1 on its phosphoinositide substrates was tested in vitro in the presence or absence of BIN1. The recombinant GST-MTM1 produced PtdIns and PtdIns5P from PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P2, respectively, contrary to GST-BIN1 or GST alone (supplementary Fig S6A online). The addition of GST-BIN1 to GST-MTM1 did not alter the quantity of PtdIns or PtdIns5P produced relative to PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P2, respectively (Fig 4A). These results show that BIN1 has no impact on the phosphatase activity of MTM1 in vitro, which was confirmed by malachite green assay using a wide range of BIN1 concentration (Fig 4B). This absence of effect is not due to the lack of interaction of BIN1 with MTM1, as showed by co-immunoprecipitation performed after the malachite green assay (Fig 4B).

Figure 4.

BIN1 does not alter MTM1 phosphoinositide phosphatase activity. (A) PtdIns and PtdIns5P reaction products were quantified by thin layer chromatography relative to the levels of remaining MTM1 substrates PtdIns3P (top panel) and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (bottom panel), in the absence of protein (ctrl) and in the presence of the recombinant GST-MTM1 alone or together with GST, GST-BIN1 wild type and GST-BIN1 p.Q573X. PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 were added in excess in order to detect either an increase or decrease in activity, explaining the 50% of dephosphorylation observed with GST-MTM1 at the termination of enzymatic reactions. Three independent experiments. Error bars ±s.e.m. (B) Malachite green assay. Top panel: dephosphorylation of PtdIns3P, PtdIns(3,5)P2 (substrates) and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (ctrl) was in presence of 10 nmol of GST-MTM1 and increasing concentration of BIN1. Bottom panel, left: Coomassie blue staining showing recombinant proteins used. Bottom, right: co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-MTM1 antibodies performed after malachite green assay. Three independent experiments. BIN1, amphiphysin 2; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; MTM1, myotubularin; PtdIns3P, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate; WT, wild type.

Patient mutations alter BIN1 conformation

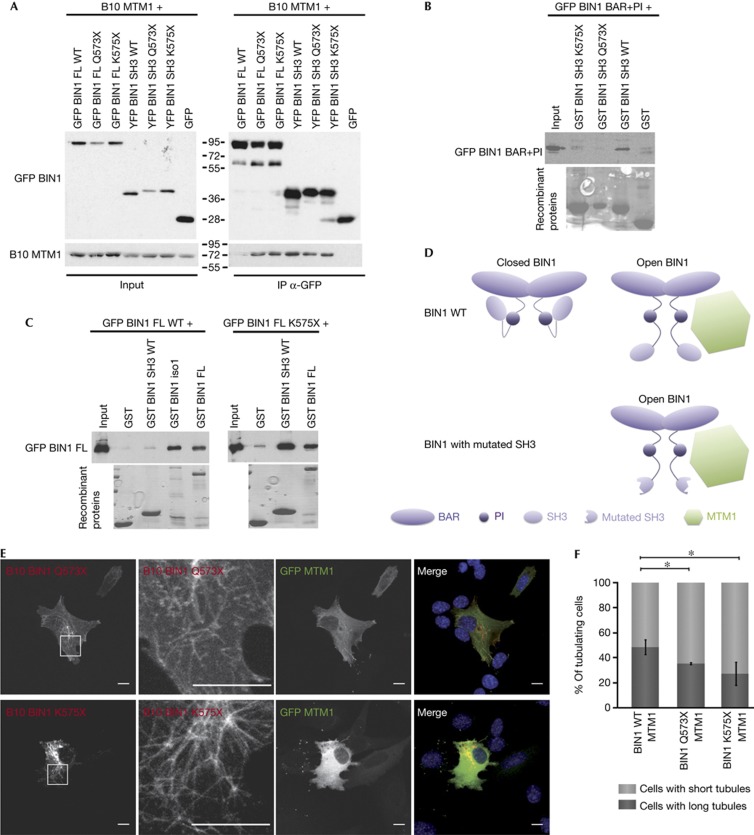

To get more insight on the pathological relevance of the MTM1–BIN1 interaction in CNM, we addressed the impact of several BIN1 patient mutations on MTM1 binding. The mutations p.K35N and p.D151N located in the BAR domain of BIN1 did not alter the co-immunoprecipitation of B10-MTM1 either with GFP-BIN1 full length or with GFP-BAR (supplementary Fig S7A online). On the contrary, B10-MTM1 co-immunoprecipitated more efficiently with GFP-BIN1 full length encompassing patient mutations in the SH3 domain (p.Q573X and p.K575X) than with wild-type GFP-BIN1 (Fig 5A). Similar results were observed after reverse co-immunoprecipitation (supplementary Fig S7B online). As the p.Q573X and p.K575X mutations did not alter the affinity of the individual SH3 domain for MTM1 compared with wild type (Fig 5A; supplementary Fig S7B online), the difference in binding observed with the full-length protein is more likely due to a difference in conformation between wild-type and mutant BIN1. Accordingly, the ability of GST-SH3 to pull down the GFP-BAR+PI domain was abolished by the p.Q573X and p.K575X mutations (Fig 5B). Moreover, wild-type GST-SH3 pulled down more efficiently p.K575X GFP-BIN1 full length, compared with wild-type GFP-BIN1 (Fig 5C), suggesting that the site interacting with the SH3 domain is more accessible on the p.K575X BIN1 protein than on the wild-type protein. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the p.Q573X and p.K575X SH3 mutations promote a constitutively open conformation of BIN1, by altering the interaction between the SH3 and the BAR+PI domains (Fig 5D), and that this open conformation binds more efficiently to MTM1. Nevertheless, p.Q573X BIN1, as wild-type protein, did not alter MTM1 phosphatase activity (Fig 4).

Figure 5.

BIN1 CNM mutations in the SH3 domain impair its conformation and its binding and regulation by MTM1. (A) Mutations affect MTM1 co-immunoprecipitation. Co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-GFP antibodies on lysates from COS-1 cells co-transfected with B10-MTM1 and GFP-BIN1 full length or SH3 domain presenting p.Q573X and p.K575X mutations. The truncated SH3 domains migrate higher than wild type as shown previously [8]. Top panel: immunoblot hybridized with anti-GFP antibodies. Bottom panel: immunoblot hybridized with anti-MTM1 antibodies. (B) Mutations alter the binding of SH3 to BAR+PI domains. Recombinant GST-SH3 wild type and mutants (p.Q573X and p.K575X) were used to pull down GFP-BAR+PI expressed in COS-1 cells. Immunoblots were hybridized with anti-GFP antibody (top panel). Recombinant proteins stained in Ponceau red (bottom panel). (C) p.K575X full-length BIN1 binds more strongly to the SH3 domain compared with wild-type BIN1. Recombinant GST-SH3, GST-BIN1 and GST-BIN1 iso1 (without the PI motif) were used to pull down wild type and p.K575X GFP-BIN1 full-length protein expressed in COS-1 cells. Immunoblots were hybridized with anti-GFP antibody (top panel). Recombinant proteins stained in Ponceau Red (bottom panel). (D) Open and closed conformation model of wild type and SH3-mutated BIN1, and consequences on MTM1 interaction. BIN1 homodimerizes via its BAR domain. BIN1 can have a closed conformation through the interaction between the SH3 and BAR+PI domains. The open conformation promotes the interaction of BIN1 with MTM1, via both BAR and SH3 domains. Mutations in the SH3 domain trigger a constitutive open conformation. (E) Patient mutations affect the regulation of BIN1 membrane tubulation. Confocal z-stack projections of C2C12 cells co-transfected with cDNAs encoding GFP-MTM1 and p.Q573X or p.K575X B10-BIN1. Immunofluorescence was performed using anti-B10 antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of C2C12 cells with short tubules versus cells with long tubules. About 100 cells/experiment were counted in three independent experiments. Error bars means ±s.e.m.; *P<0.05 data are considered significant. BAR, BIN/Amphiphysin/Rvs; BIN1, amphiphysin 2; FL, full length; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; MTM1, myotubularin; WT, wild type.

Mutations alter the regulation of BIN1 by MTM1

The consequences of p.Q573X and p.K575X BIN1 mutations on the regulation of BIN1 membrane tubulation by MTM1 were then tested. Expression of GFP-MTM1 enhanced membrane tubulation mediated by BIN1 mutants in ∼35% to 25% of cells (Fig 5E,F), which is less than observed in the case of wild-type BIN1 (about 50% of cells, Fig 2A,B). The increased MTM1 binding promoted by the BIN1 SH3 mutations might impair the MTM1 positive role on BIN1 membrane tubulation. Alternatively, these SH3 mutations might impact the membrane tubulation properties of BIN1 independently of MTM1, although previous experiments in transfected COS-1 cells did not detect a strong alteration [8].

In this study, we identified MTM1 as a novel binding partner of BIN1 in skeletal muscle and as a regulator of the membrane tubulation properties of BIN1 in muscle cells. Several BIN1 mutations causing CNM alter the conformation of BIN1 and its binding and regulation by MTM1. Altogether, these data provide a first molecular link between two forms of CNM and support that alteration of the MTM1–BIN1 complex is of pathological relevance. As mutations in the BAR domain strongly impair membrane tubulation [8], and as we showed here that mutations in the SH3 domain impact on the regulation of BIN1-mediated membrane remodelling by MTM1, we propose that alteration of BIN1-mediated membrane tubulation account for the primary defects leading to the disease in the muscle, both in BIN1- and MTM1-related CNM.

METHODS

Muscle subcellular fractionation, in vitro lipid phosphatase assay and malachite green assay were performed according to Saito et al [22], Tronchère et al [6] and Taylor and Dixon [23], respectively. Supplementary Methods online: full description of materials and detailed protocols for the above, constructs, cell culture and transfections, production of GST-fusion proteins, western blot, statistics.

Co-immunoprecipitation assays. COS-1 cells were lysed 24 h after co-transfection (Lipofectamine 2000, Invitrogen) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitors (cOmplete EDTA free, Roche). Mouse muscle homogenates were performed on membrane extracts using alkaline carbonate extraction developed by Okamoto et al [24] using 100 mM sodium carbonate, pH11.5. Buffer was adjusted to 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH7.5 and 300 mM and immunoprecipitations were performed overnight on protein G-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) using mouse anti-B10 and anti-GFP antibodies (IGBMC) or mouse anti-MTM1 (1G1, IGBMC) and anti-BIN1 (C99D, Sigma-Aldrich). After several washes, bound proteins were analysed by western blot.

Pull-down assays. Whole-cell homogenates from transfected COS-1 cells obtained as above, or B10-MTM1 produced in vitro by coupled transcription/translation kit (TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate Systems, Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, were incubated overnight with purified GST-fusion proteins coupled to glutathione beads. After several washes, bound proteins were analysed by western blot.

Immunofluorescence. C2C12 cells (transfected myoblast or differentiated myotubes) or COS-1 were fixed in 4% PFA. Isolated fibres were dissected from entire muscles, fixed in 4% PFA, incubated 30 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 0.1 M glucose and afterwards overnight in PBS 30% sucrose. Immunofluorescence was performed on permeabilized cells or fibres, with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies in PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 3% fetal calf serum for cells or in PBS, 50 mM NH4Cl, 0.2% donkey serum, 0.1% Triton X-100 for fibres. Images were obtained by epi-fluorescence microscopy or confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP2RS, 1,024 × 1,024 pixel images, zoom × 2, three lines average).

Membrane tubulation analysis. In C2C12, only cells presenting membrane tubules were analysed and tubules were considered short when they were shorter or equal to twice their diameter (supplementary Fig S3B online). About 100 cells/experiment were counted, in at least three independent experiments. In COS-1 cells, about 200 transfected cells (with/without tubules) were counted in two independent experiments. For tubule length measurement in COS-1 cells, ImageJ software was used; tubules were considered long if their length range between ≈5 μm and ≈15 μm and short for a length between ≈0.5 μm and ≈1 μm. Twenty to thirty tubules per cell were counted in about 90 transfected cells (ratio long tubules/short tubules) in two independent experiments.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge J. Böhm, L. Davignon, M. Koch, P. Kessler, J-D. Fauny for technical assistance. This study was supported by INSERM, CNRS, UdS, Collège de France, FRM, E-rare program, ANR and AFM. B.R. was supported by a fellowship from ARC.

Authors contributions: B.R., K.H., C.G., H.T., V.T. performed the experiments and analysed the data. B.R. and J.L. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Romero NB, Bitoun M (2011) Centronuclear myopathies. Semin Pediatr Neurol 18: 250–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Kress W, Mandel JL (2001) Diagnosis of X-linked myotubular myopathy by detection of myotubularin. Ann Neurol 50: 42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Hu LJ, Kretz C, Mandel JL, Kioschis P, Coy JF, Klauck SM, Poustka A, Dahl N (1996) A gene mutated in X-linked myotubular myopathy defines a new putative tyrosine phosphatase family conserved in yeast. Nat Genet 13: 175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau F, Laporte J, Bodin S, Superti-Furga G, Payrastre B, Mandel JL (2000) Myotubularin, a phosphatase deficient in myotubular myopathy, acts on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate pathway. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2223–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GS, Maehama T, Dixon JE (2000) Inaugural article: myotubularin, a protein tyrosine phosphatase mutated in myotubular myopathy, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8910–8915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronchere H, Laporte J, Pendaries C, Chaussade C, Liaubet L, Pirola L, Mandel JL, Payrastre B (2004) Production of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate by the phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase myotubularin in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 279: 7304–7312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoasii L et al. (2012) Phosphatase-dead myotubularin ameliorates X-linked centronuclear myopathy phenotypes in mice. PLoS Genet 8: e1002965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot AS et al. (2007) Mutations in amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) disrupt interaction with dynamin 2 and cause autosomal recessive centronuclear myopathy. Nat Genet 39: 1134–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann B, Koch D, Kessels MM (2011) Let's go bananas: revisiting the endocytic BAR code. EMBO J 30: 3501–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter BJ, Kent HM, Mills IG, Vallis Y, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT (2004) BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science 303: 495–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Marcucci M, Daniell L, Pypaert M, Weisz OA, Ochoa GC, Farsad K, Wenk MR, De Camilli P (2002) Amphiphysin 2 (Bin1) and T-tubule biogenesis in muscle. Science 297: 1193–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima C, Hashimoto A, Yabuta I, Hirose M, Hashimoto S, Kanaho Y, Sumimoto H, Ikegami T, Sabe H (2004) Regulation of Bin1 SH3 domain binding by phosphoinositides. Embo J 23: 4413–4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MH, David C, Ochoa GC, Freyberg Z, Daniell L, Grabs D, Cremona O, De Camilli P (1997) Amphiphysin II (SH3P9; BIN1), a member of the amphiphysin/Rvs family, is concentrated in the cortical cytomatrix of axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier in brain and around T tubules in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 137: 1355–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint A et al. (2011) Defects in amphiphysin 2 (BIN1) and triads in several forms of centronuclear myopathies. Acta Neuropathol 121: 253–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Blondeau F, Gansmuller A, Lutz Y, Vonesch JL, Mandel JL (2002) The PtdIns3P phosphatase myotubularin is a cytoplasmic protein that also localizes to Rac1-inducible plasma membrane ruffles. J Cell Sci 115: 3105–3117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoasii L et al. (2013) Myotubularin and PtdIns3P remodel the sarcoplasmic reticulum in muscle in vivo. J Cell Sci 126: 1806–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq A, Robinson IM, McMahon HT, Skepper JN, Su Y, Zelhof AC, Jackson AP, Gay NJ, O'Kane CJ (2001) Amphiphysin is necessary for organization of the excitation-contraction coupling machinery of muscles, but not for synaptic vesicle endocytosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev 15: 2967–2979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando P, Sandoz JS, Ding W, de Repentigny Y, Brunette S, Kelly JF, Kothary R, Megeney LA (2009) Bin1 SRC homology 3 domain acts as a scaffold for myofiber sarcomere assembly. J Biol Chem 284: 27674–27686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qusairi L et al. (2009) T-tubule disorganization and defective excitation-contraction coupling in muscle fibers lacking myotubularin lipid phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 18763–18768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JJ, Vreede AP, Low SE, Gibbs EM, Kuwada JY, Bonnemann CG, Feldman EL (2009) Loss of myotubularin function results in T-tubule disorganization in zebrafish and human myotubular myopathy. PLoS Genet 5: e1000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugier C et al. (2011) Misregulated alternative splicing of BIN1 is associated with T tubule alterations and muscle weakness in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Med 17: 720–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Seiler S, Chu A, Fleischer S (1984) Preparation and morphology of sarcoplasmic reticulum terminal cisternae from rabbit skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 99: 875–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GS, Dixon JE (2003) PTEN and myotubularins: families of phosphoinositide phosphatases. Methods Enzymol 366: 43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Schwab RB, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP (2001) Analysis of the association of proteins with membranes. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter 5:Unit 5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.