Abstract

The clinical pharmacokinetics and exposure-toxicity relationship were determined for EC145, a conjugate of folic acid and the Vinca alkaloid desacetylvinblastine hydrazide (DAVLBH), in cancer patients. EC145 plasma concentration and toxicity data were obtained from a first-in-man phase I study and analyzed by nonlinear mixed effect modeling with NONMEM. EC145 concentration-time profile after intravenous administration was well described by a 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process from the central compartment. BSA was identified as a significant covariate on EC145 clearance, accounting for 14.6% of interindividual variation on EC145 clearance. Population estimates for the clearance, steady-state volume of distribution, distribution, and elimination half-lives were 56.1 L/h, 26.1 L, 6 minutes, and 26 minutes, respectively. Constipation and peripheral neuropathy were the most common and clinically relevant toxicities. The clearance and area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) were significant predictors for the incidence of EC145-induced constipation but not peripheral neuropathy. In conclusion, EC145 is rapidly distributed and eliminated in cancer patients. BSA is a statistically significant covariate on EC145 clearance, but its clinical relevance remains to be defined. EC145-induced constipation occurs at a higher frequency in the patients with lower EC145 clearance, where the drug exposure tends to be higher.

Keywords: EC145, folate conjugate, clinical pharmacokinetics, exposure-toxicity relationship

The mammalian folate receptor (FR) is a family of homologous glycopolypeptides that bind folate compounds and antifolates with high affinity.1 The FR is overexpressed by a variety of human cancers, including cancers of the ovary, brain, lung, kidney, breast, and endometrium.2–5 Thus, the FR acts as a tumor marker and also a high-affinity tumor-specific receptor for folate-linked conjugates. Linkage of a drug to folic acid can enable tumor-specific delivery of either imaging or therapeutic agents into the tumors expressing the FR.6,7 Once the folate-drug conjugate binds to the FR, endocytosis occurs and the receptor changes conformation, releasing the drug within the acidic milieu of the endosome. The FR then recycles to the cell surface for another round of folate conjugate uptake. Eventually, the released drug diffuses across the endosomal membrane and exerts its pharmacological effects within the cell. Folate conjugate delivery systems have displayed enhanced tumor-specific killing and reduced unwanted cytotoxicity compared to their unconjugated drug counterparts, representing a promising treatment for human cancers with overexpression of the FR.6,8,9

EC145 is a water-soluble folate conjugate of desacetylvinblastine monohydrazide (DAVLBH), which is constructed with the DAVLBH drug moiety attached to a hydrophilic folate-peptide compound via an endosome-cleavable disulfide bond.8 DAVLBH is a Vinca alkaloid derivative that is capable of disrupting the formation of the mitotic spindle and thus inhibiting cell division and causing cell death. EC145 binds specifically to the FR with a high affinity.8 Preclinical studies have demonstrated that EC145 produces a highly potent and specific antitumor activity against FR-positive tumors, and it significantly improves the therapeutic index of DAVLBH.8,9

EC145 has been evaluated in a phase I trial in patients with refractory or metastatic solid tumors, where EC145 was administered as an intravenous bolus injection or a 1-hour infusion on days 1, 3, 5 (week 1) and 15, 17, 19 (week 3) of a 28-day cycle.10 Two modes of intravenous administration were tested in this trial to examine if the incidence of drug-induced toxicity (ie, fast onset ileus/severe constipation) was associated with a higher maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) resulting from an intravenous bolus injection. EC145 was generally well tolerated. Constipation and peripheral neuropathy were the most common and clinically significant toxicities, based on which the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was defined.10 The MTD for the bolus injection was found to be the same to the MTD for the 1-hour infusion mode. For the sake of patient convenience, the bolus injection mode was thus chosen for further clinical development. EC145 is currently being evaluated in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian, and endometrial cancers in phase II trials.

Optimal use of FR-targeted therapies requires an understanding of the mechanisms underlying the tumor uptake of folate conjugates, including the rate of receptor binding, FR saturation concentration, rate of FR recycling, and retention time of the conjugated drug in the tumor cell.11 In addition, knowledge of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (or toxicity) relationship of the folate conjugate in patients can provide important information for defining an optimal dosing regimen to achieve maximum clinical benefit. The present study represents the first-in-man clinical and pharmacological experience with EC145. In this report, a population pharmacokinetic model was developed to characterize the clinical pharmacokinetics of EC145 in patients with solid tumors and to identify covariates that influence the pharmacokinetics. In addition, the relationship of EC145 pharmacokinetics and its common and clinically relevant toxicities (ie, constipation and peripheral neuropathy) was examined.

METHODS

Clinical Trial and Patients

The pharmacokinetic and toxicity data used in the analysis were obtained from an open-labeled, dose-escalating phase I study (Endocyte Protocol EC-FV-01) that involved a total of 32 cancer patients treated with single-agent EC145. EC145 was administered as either an intravenous bolus injection on days 1, 3, 5 (ie, week 1) and days 15, 17, 19 (ie, week 3) of a 4-week cycle at the dose levels of 1.2, 2.5, and 4.0 mg, with a cohort of 3, 10, and 3 patients, respectively, or as a 1-hour infusion administered on days 1, 3, 5 (ie, week 1) and days 15, 17, 19 (ie, week 3) of a 4-week cycle at the dose levels of 2.5 and 3.0 mg, with a cohort of 10 and 6 patients, respectively.

Patients with histologically confirmed solid tumors refractory to standard therapy were eligible for participation in the trials. Additional eligibility criteria included the following: age >18 years; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2; adequate marrow function (absolute neutrophil count ≥1.5 × 109/L, platelet count ≥100 × 109/L, hemoglobin ≥9 g/dL); and adequate liver and kidney functions (serum transaminase ≤2.5 times of institution upper limit of normal (ULN), total bilirubin ≤1.3 × ULN, serum creatinine ≤1.5 × ULN, or creatinine clearance ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for patients with serum creatinine level above 1.5 × ULN). Patients may not have had previous anticancer treatment for at least 28 days prior to study entry. The study protocol was approved by the Investigational Review Board (IRB) in the study center, and written informed consent was obtained for all patients.

Pharmacokinetic Study

During cycle 1, serial blood samples were collected on days 1 and 3. For the intravenous bolus injection, blood samples were collected within 15 minutes prior to the injection and at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 minutes after the injection. For the 1-hour intravenous infusion, blood samples were collected within 15 minutes prior to the infusion and after the start of the infusion at 30, 60 (the end of the 1-hour infusion), 75, 90, 105, and 120 minutes. At each sampling time point, the first 1 mL of blood drawn from the venous catheter was discarded to avoid dilution of the sample with the solution in the catheter, and about 5 mL of blood was collected into a K3 EDTA tube. The plasma was separated by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 minutes and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Bioanalytical Methods

EC145 and DAVLBH were quantified in plasma using a validated high-performance liquid chromatographic method with tandem mass spectrometric detection (LC-MS/MS) as described below. EC145 and DAVLBH were extracted from plasma by automated cation exchange solid phase extraction (SPE) using a Strata-X-C plate (Strata-X-C, 96-well, 30 mg, Phenomenex, Torrance, California). Briefly, vindesine sulfate (VDS) and isotope-labeled EC145 were added as internal standards prior to the extraction. Five hundred microliters of each plasma sample was loaded to the SPE plate that had been preconditioned with methanol followed by 2% formic acid solution. The compounds were eluted with ammonium hydroxide in methanol solution. The elute was collected and evaporated to dryness. The residue was reconstituted in 100 µL of methanol solution containing 0.5% formic acid and subjected to the LC-MS/MS system. Chromatographic separation was achieved on an XBridge column (C18, 2.1 × 50 mm, 3.5 µm, Waters Corporation, Milford, Massachusetts) with a gradient 0.5% aqueous formic acid/methanol mobile phase. The analytes and internal standards were monitored using a Sciex 400 mass spectrometric detector (MDS Analytical Technologies, Concord, Ontario, Canada) with a TurboIonSpray probe in the position ionization mode. The following parent-to-product ion transitions were monitored: m/z, 959.1→295.2 for EC145; m/z, 769.5→355.2 for DAVLBH; m/z, 964.0→295.0 for isotope-labeled EC145; and m/z, 754.3→355.5 for VDS. The calibration curves for EC145 and DAVLBH were set over the concentration range of 10 to 2500 ng/mL and 4 to 1000 ng/mL, respectively. The lower limits of quantitation (LLOQ) were 10 and 4 ng/mL for EC145 and DAVLBH, respectively. The accuracy and within- and between-day precisions were within the acceptance criteria for bioanalytical assays.

Assessment of Toxicity

Toxicity was graded according to standard CTCAE (v3.0) toxicity criteria (ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCA-Ev3.pdf). Drug-related adverse events are those that are considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to the experimental therapy. For the evaluation of exposure-toxicity relationship, the grade of toxicity assigned to a patient was the worst grade of the toxicity experienced during the first cycle of treatment.

Noncompartmental Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Plasma EC145 concentration versus actual sampling time data for each individual patient were analyzed by a noncompartmental method using the software program WinNonlin version 5.2 (Pharsight Corporation, Cary, North Carolina). The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time of occurrence for maximum concentration (Tmax) were obtained by visual inspection of the plasma concentration-time curves after the drug administration. The total area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to the last measurable time point (AUClast) was calculated using the linear and logarithmic trapezoidal method for ascending and descending plasma concentrations, respectively. The total area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0-∝) was calculated as the sum of AUClast and the extrapolated area, which was calculated by the last observed plasma concentration divided by the terminal rate constant (λz), where λz was estimated by terminal log-linear phase of the plasma concentration-time curve.

Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis

The population pharmacokinetic model was developed in 2 steps: (1) basic (structural) model development, and (2) covariate model development. All analyses were performed with the first-order conditional method (FOCE) with interaction as implemented in the NONMEM program (version VI) (University of California, San Francisco, California). Xpose 4.0/R2.6.2 (Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden) was used for graphical diagnostics and covariate screen.

The structural model was built to fit multiple-dose EC145 plasma concentration-time profiles following intravenous bolus injection and 1-hour infusion from all patients simultaneously. EC145 concentration data were log-transformed in the data file. A 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process from the central compartment was chosen to fit EC145 concentration-time data. Mean population pharmacokinetic parameters, interindividual variability (IIV), residual error (intraindividual variability), and interoccasion variability (IOV) were assessed in the population pharmacokinetic model. IIV for each pharmacokinetic parameter was modeled with the exponential function. Residual error was modeled with a combination method including an additive and a proportional part. IOV was modeled with exponential function. The pharmacokinetic parameter values for individual patients were obtained by POSTHOC Bayesian estimation.

The covariate model building is a stepwise process. A screen for potential significant covariates was performed with a generalized additive model (GAM) using Xpose 4.0/R 2.6.2 software (Uppsala University).12 The potential covariates as listed in Table I as well as administration route and treatment day were screened on the Bayesian estimated pharmacokinetic parameters from the structure model, that is, CL, V1, V2, Q, where CL is the clearance, V1 and V2 are the volume of distribution for the central and for the peripheral compartment, respectively, and Q is the intercompartment clearance. When a covariate value was missing in a patient, this covariate value was replaced by the population median value. The frequency of missing covariates was < 10%. The potential covariates selected from GAM analysis were assessed in the covariate model as linear, exponential, or power function. Continuous covariates (eg, BSA) were centered around their median values, and dichotomous covariates were coded as 0 or 1 (eg, 0 indicates male, and 1 indicates female). Discrimination between hierarchical models was made by comparison of the NONMEM objective function value (OFV) and by visual inspection of the goodness-of-fit plots. The difference between the OFV for 2 hierarchical models is approximately χ2 distributed, where the degrees of freedom are based on the difference between the numbers of estimated parameters. A significant covariate was selected to be retained in the final model if addition of the covariate resulted in a decrease in OFV >3.875 (P < .05) during the forward covariate model building and removal of this covariate resulted in an increase in OFV >10.828 (P < .001) during the stepwise backward model reduction. In addition, the increase in precision of the parameter estimate (ie, reduction of % relative standard error of prediction) and reduction in interindividual variability were used as another indicator of the improvement of the goodness of fit.

Table I.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Median (Range) | |

|---|---|

| Baseline screening | |

| Sex (male/female)a | 19/13 |

| Race (white/black)a | 21/11 |

| Age, y | 59 (33–78) |

| Weight, kg | 73 (48–121) |

| Height, cm | 173 (155–185) |

| BSA,b m2 | 1.86 (1.44–2.49) |

| Pretreatment clinical chemistry | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) |

| CrCl,c mL/min | 83 (34–210) |

| ALT, IU/L | 24 (10–144) |

| Alk phos, IU/L | 107 (57–477) |

| AST, IU/L | 26 (14–92) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) |

| Serum albumin, mg/dL | 3.8 (1.9–4.5) |

| Hematocrit, % | 35 (28–43) |

| Total protein, mg/dL | 7.1 (5.8–8.8) |

| Serum folate, nmol/L | 14 (8.1–24) |

| RBC folate, nmol/L | 1020 (559–1576) |

| RBC count, ×109/L | 4.12 (2.97–4.93) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 279 (122–688) |

| Tumor typea | |

| Colorectal | 8 |

| Lung | 6 |

| Pancreas | 2 |

| Renal cell | 1 |

| Breast | 1 |

| Head and neck | 6 |

| Ovarian | 2 |

| Esophageal | 1 |

| Bladder | 1 |

| Thymoma | 1 |

| Appendiceal | 1 |

| Nerve sheath | 1 |

| Thyroid | 1 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartase aminotransferase; Alk phos, alkaline phosphatase; BSA, body surface area; RBC, red blood cell.

Data indicate number of patients.

Exposure-Toxicity Analysis

Relationships between (1) observed days 1 and 3 EC145 Cmax, (2) days 1 and 3 AUC estimated by noncompartmental analysis, and (3) EC145 clearance estimated from the final population pharmacokinetic model, and the incidence of the toxicities (ie, constipation and peripheral neuropathy) were examined. Because the worst grade of constipation and peripheral neuropathy was scored as a categorical variable (ie, 0, 1, 2, and 3), the probability (P) of each individual score of constipation or peripheral neuropathy might be linked to drug exposure by use of the logistic regression model.13 However, based on the data from a small population of 32 patients, a significant association between EC145 pharmacokinetic parameter and individual score of constipation or peripheral neuropathy was not found. Hence, in the final logistic regression model, constipation and peripheral neuropathy was treated as a dichotomous categorical variable (0 and 1), in which 0 represented absence of the toxicity (ie, constipation or peripheral neuropathy) and 1 represented occurrence of the toxicity (ie, constipation or peripheral neuropathy; including grade 1, 2, and 3). The logistic regression model was applied to predict the probability (P) of the occurrence of the toxicity with a single predictor (x) (ie, EC145 AUC or clearance), as described previously,14 where the drug effect was introduced in the model as a linear function (ie, slope × CL).

The exposure-toxicity relationship was analyzed with the Laplacian approximation of the loglikelihood method as implemented in the NONMEM program (version VI). An increase of OFV >3.84 (P < .05) with the exclusion of the drug effect from the model (ie, slope set as 0) was adopted to indicate the significant association between the pharmacokinetic parameter and incidence of the toxicity.

RESULTS

Plasma Exposure to EC145 and DAVLBH

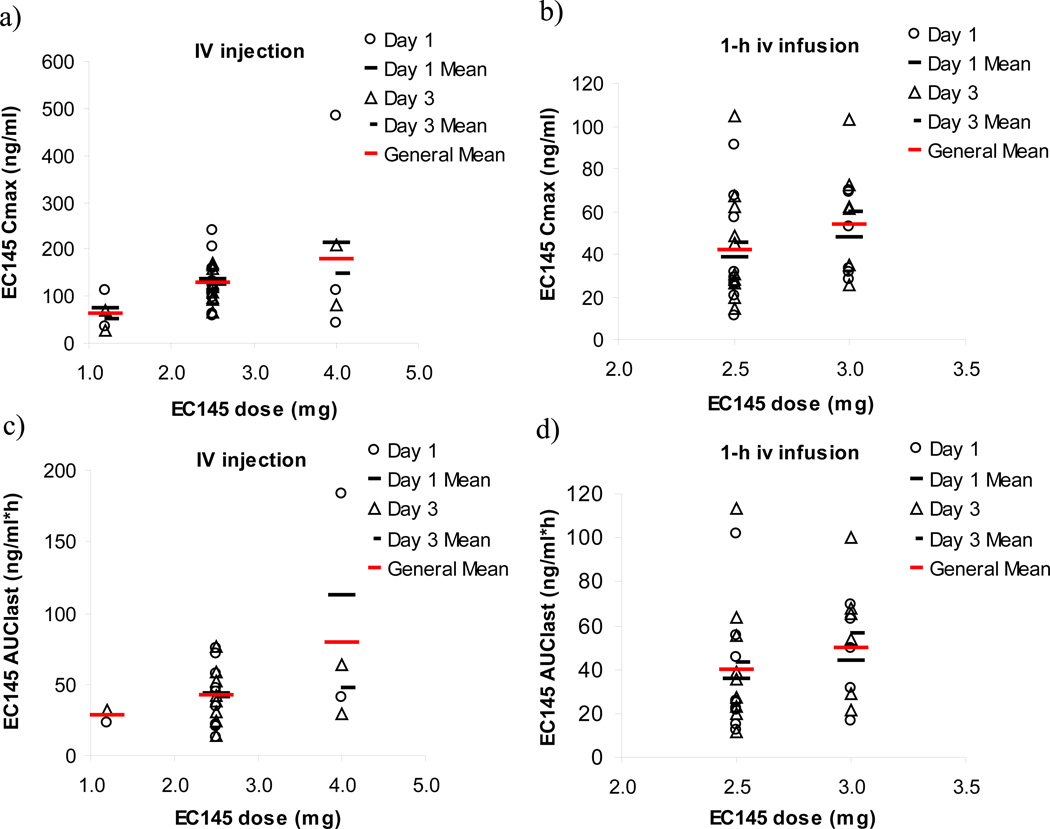

Following an intravenous injection at EC145 doses of 1.2, 2.5, and 4.0 mg, the mean values of the Cmax were 61, 129, and 179 ng/mL, respectively, and the mean values of AUClast were 28, 42, and 80 h*ng/mL, respectively (Figure 1). Following a 1-hour infusion of EC145 at doses of 2.5 and 3.0 mg, the Cmax was achieved at the end of infusion, with the mean values of 42 and 54, respectively, and the mean values of AUClast were 40 and 50 h*ng/mL, respectively (Figure 1). Compared to an intravenous bolus injection at the dose of 2.5 mg, a 1-hour infusion resulted in a lower Cmax (mean, 42 vs 129 ng/mL) but equivalent AUC (40 vs 42 h*ng/mL) (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in EC145 plasma exposure on days 1 and 3 (P > .05) at all dose levels evaluated (Figure 1). The Cmax and AUClast were increased in proportion to the increasing dose of EC145 from 1.2 to 4.0 mg (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationships between EC145 dose and Cmax (A and B) and AUC (C and D) following an intravenous bolus injection and a 1-hour infusion. Data are presented as individual patient parameters and mean values.

The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for DAVLBH was set at 4 ng/mL. The unlinked component, DAVLBH, was undetectable (below the LLOQ) in the pretreatment and posttreatment plasma samples in virtually all patients. This was consistent with in vitro observations that little EC145 was degraded to release free drug.15

Population Pharmacokinetic Model

The EC145 plasma concentration-time profile following intravenous administration was well described by a 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process from the central compartment. The present population analysis confirmed the linear pharmacokinetic characteristics of EC145 when the dose was escalated from 1.2 to 4.0 mg, as demonstrated by the noncompartmental analysis showing the Cmax and AUC were increased in proportion to the increasing dose of EC145 (Figure 1).

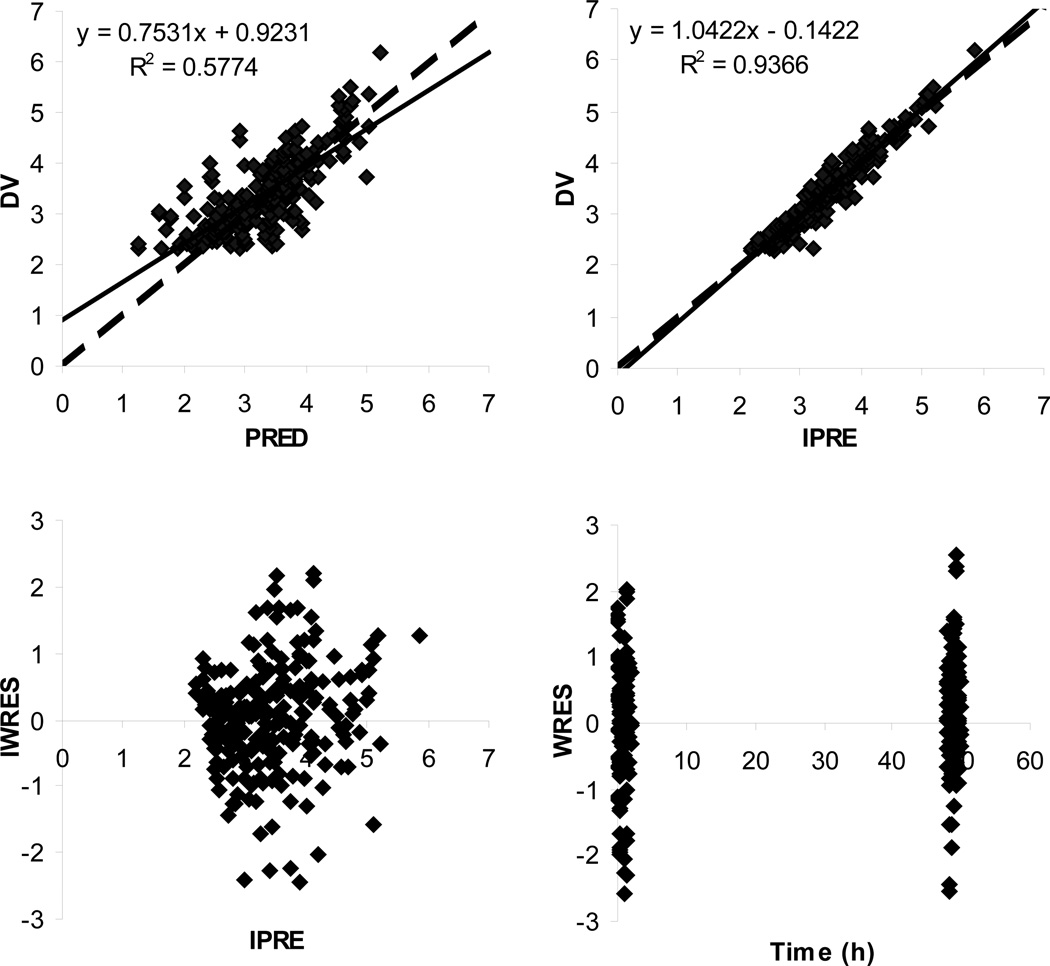

During the covariate model building, the following potential covariates selected from GAM analysis were tested: body surface area (BSA) and bilirubin on Q; creatinine clearance (CrCL) and race on V2; CrCL on V1; and BSA, race, and alkaline phosphatase on CL. With BSA being added as the covariate on Q (covariate model I), the OFV was decreased by 7.22 (P < .05) compared to the structure model; further additions of bilirubin on Q, CrCL and race on V2, CrCL on V1, or race on CL resulted in a negligible improvement in the fitting (with the decrease in OFV <3.875; P > .05). Based on the covariate model I, the addition of alkaline phosphatase on CL (covariate model II) resulted in a decrease of the OFV by 6.68 (P < .05), and further addition of BSA on CL (covariate model III) reduced the OFV by 8.92 (P < .05). Covariate model III was therefore selected as the full covariate model. During the stepwise backward model reduction, the removal of BSA from Q increased the OFV by 8.55 (P > .001); further removal of alkaline phosphatase from CL resulted in an increase of the OFV by 4.09 (P > .001); and further removal of BSA from CL resulted in an increase of the OFV by 11.16 (P < .001). Therefore, only BSA was retained in the final model as a significant covariate on the CL. The final pharmacokinetic model consisted of a 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process from the central compartment, with BSA being included as a significant covariate on EC145 CL. The goodness-of-fit plots from the final pharmacokinetic model are shown in Figure 2. The predicted concentrations were well correlated with the observations, and the residual plots indicated no prediction bias.

Figure 2.

Basic goodness-of-fit plots from the final 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process and with BSA being introduced as a significant covariate on CL. Observed and predicted concentrations are shown as log-transformed. The solid lines are linear regression lines, and the dashed lines are lines of identity. DV, observed concentration; PRED, population predicted concentration; IPRE, individual predicted concentration; WRES, weighted residue; IWRES, individual weighted residues.

The typical population pharmacokinetic parameters and respective interindividual variability, estimated from the structural and final pharmacokinetic models, are presented in Table II. EC145 showed a systemic clearance of 56.1 L/h, with an interindividual variability (IIV) of 48% and interoccasion variability (IOV) of 8.0%. BSA was identified as a significant covariate on EC145 clearance. However, the addition of covariate BSA on CL accounted for only 14.6% of unexplained interindividual variability on EC145 clearance, suggesting other clinical covariates that were not tested in the present study may account for a larger proportion of the interindividual variability. EC145 is distributed and cleared from the body rapidly, with the population estimates for the distribution and elimination half-lives of 6 and 26 minutes, respectively. The population estimate of steady-state volume of distribution (Vss) of EC145 was 26 L, indicating a distribution in excess of blood volume.

Table II.

Population Pharmacokinetic Parameters of EC145, Expressed as the Estimate (with % relative standard error of estimation), and the Corresponding Interindividual Variability

| Structural Modela | Final Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Covariate | None | TVCL = THETA(1)·(BSA/1.87)THETA(7) |

| OFV | −248.138 | −258.339 |

| TVCL, L/h | 54.3 (9.9) | 56.1b (8.1) |

| TVV1, L | 16.7 (13.4) | 16.4 (12.6) |

| TVV2, L | 9.8 (21.0) | 9.7 (15.0) |

| TVQ, L/h | 30.9 (18.3) | 31.3 (16.9) |

| THETA(5)c | 0.239 (9.4) | 0.239 (9.3) |

| THETA(6)d | 0.002 (118) | 0.002 (11.3) |

| THETA(7) | − | 2.61 (21.1) |

| IIV of CL, % | 48 (26) | 41 (31) |

| IIV of V1, % | 64 (26) | 64 (27) |

| IIV of V2, % | 49 (140) | 48 (120) |

| IIV of Q, % | 32 (96) | 34 (95) |

| IOV of CL, % | 8.2 (86) | 8.0 (88) |

TV, typical value; CL, systemic clearance; V1, volume of distribution of the central compartment; V2, volume of distribution of peripheral compartment; Q, intercompartment clearance; IIV, interindividual variability (% CV); IOV, interoccasion variability.

The structural model is a 2-compartment model with a first-order elimination process from the central compartment.

Typical value for an individual with the median value of BSA (1.87), calculated from CL = THETA(1) · (BSA/1.87)THETA(7).

Additive component in residue error model.

Proportional component in residue error model.

Exposure-Toxicity Relationship

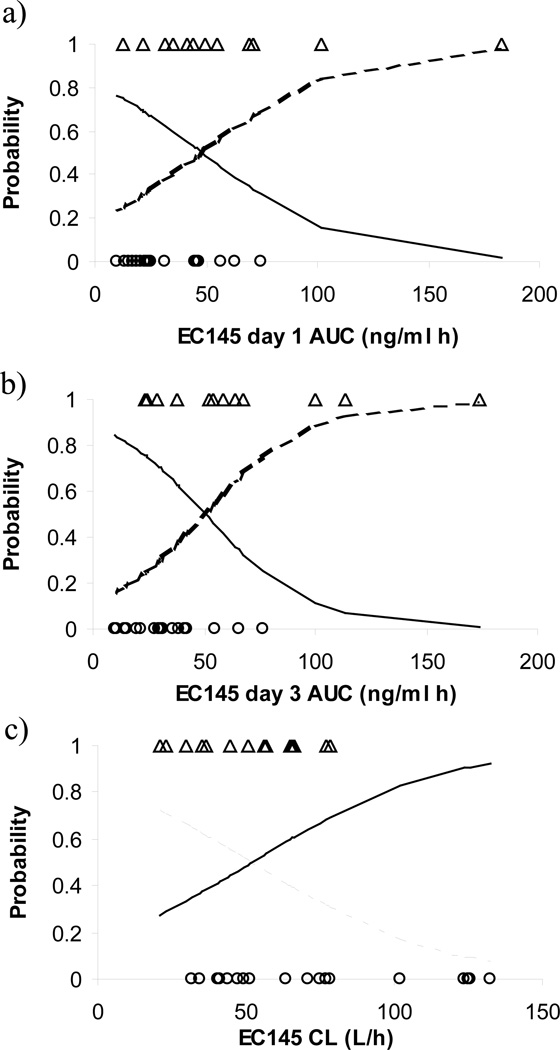

No hematological toxicities were observed following either a bolus intravenous injection or a 1-hour infusion of EC145 at the tested dose levels. At least one drug-related adverse event was reported in 12 (75.0%) of the 16 patients who received EC145 by bolus intravenous injection and in 14 (87.5%) of the 16 patients who received EC145 as a 1-hour intravenous infusion. No clinically important differences in the incidence of drug-related adverse events were observed between the bolus injection and 1-hour infusion routes of administration. Across all cycles, decreased gastrointestinal motility (ie, constipation) and peripheral sensory neuropathy were the most commonly reported drug-related toxicity (reported in >5 of the 32 patients). Table III presents the incidence of constipation and peripheral neuropathy during the first cycle of treatment in each cohort. Constipation appeared dose dependent, with more severe toxicity occurring at higher EC145 dose levels (Table III). Logistic regression analysis indicated that EC145 clearance (estimated from the final population pharmacokinetic model) as well as day-1 and -3 AUClast (estimated from noncompartmental analysis) were significant predictors for the incidence of constipation (Figure 3). Inclusion of CL, day-1 AUClast, or day-3 AUClast as a linear function on the probability of constipation reduced the OFV by 4.90 (P < .05), 4.57 (P < .05), and 7.67 (P < .05), respectively, compared to the model that excluded the drug effect. The values of slopes were estimated as −0.031, 0.031, and 0.042 for EC145 clearance, day-1 AUClast, and day-3 AUClast, respectively. No significant association was found between EC145 Cmax and the incidence of constipation. The incidence of peripheral neuropathy was not associated with the CL, AUC, or Cmax of EC145.

Table III.

Incidence of the Most Common Toxicities, Constipation and Peripheral Neuropathy, During the First Cycle of Treatment With EC145 in Each Cohort

| Constipation | Peripheral Neuropathy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 |

| 1.2 mg, IV injection (n = 3) | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.33 | 0 |

| 2.5 mg, IV injection (n = 10) | 0.6 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2.5 mg, 1-hour infusion (n = 10) | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 3.0 mg, 1-hour infusion (n = 6) | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

| 4.0 mg, IV injection (n = 3) | 0.33 | 0 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0 |

IV, intravenous.

Figure 3.

Correlation between EC145 day-1 AUClast (A), day-3 AUClast (B), and clearance (C) and the incidence of constipation (≥grade 1) in patients receiving intravenous EC145 at the dose ranging from 1.2 to 4.0 mg. The solid and dashed lines represent the logistic regression model predicted probability of no constipation and constipation, respectively. The insertion of observed events of constipation (Δ) and no constipation (○) at probability levels of 1 and 0 is purely for illustration.

DISCUSSION

This report summarizes the clinical pharmacokinetics for the first-in-man investigation of EC145 in patients with refractory solid tumors. The EC145 pharmacokinetic profile is characterized by a rapid distribution and elimination phase, with the population estimates for the distribution and elimination half-lives of 6 and 26 minutes, respectively. This is in agreement with the rapid tissue distribution and elimination phenomenon that has been observed for EC145 and other folate conjugates (eg, folatemitomycin and 99mTc-EC20) in animal models.9,16,17 In vitro studies have shown that 3 distinct low molecular weight folate derivatives bound rapidly to a panel of FR-expressing cancer cells and approached receptor saturation within the initial 30 minutes of incubation, suggesting that FR binding is rapid when permeability barriers are absent.11 The short distribution half-life of EC145 observed in humans indicates that the uptake of the conjugate by the FR-expressing tissues in vivo is rapid. Such a rapid tissue distribution is generally desirable for receptor-targeted therapies because the conjugate can lose potency due to inactivation reactions (eg, hydrolysis, oxidation, reduction) in circulation as time to reach the targeted tissue increases.11 The rapid clearance of EC145 from circulation in humans may be a consequence of its rapid elimination by both the liver and kidney. Recent data in rats suggest that EC145 is eliminated by both the liver and kidney. Excretion through the kidney results in predominantly intact EC145 in the urine with little free DAVLBH, while elimination through the liver results in a large fraction of the EC145 molecule being metabolized with subsequent free DAVLBH being released into the bile (unpublished data). Such a rapid elimination is desirable for FR-targeted therapies because the conjugates that do not encounter a receptor should be rapidly removed from the body before they cause toxicity to the nontargeted tissues.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis suggests that EC145 has a systemic clearance of 56.1 L/h with an interindividual variability of 48% in cancer patients. BSA was identified as the statistically significant covariate on EC145 clearance. However, because the addition of the BSA covariate on the clearance accounted for only 14.6% of unexplained interindividual variability on EC145 clearance, a definitive understanding of the clinical relevance of BSA-based dosing on EC145 pharmacokinetics requires further investigation.

The EC-FV-01 phase I study suggests that EC145 clinical toxicity is significantly less than that exhibited during the administration of free Vinca alkaloid chemotherapeutic agents. This correlates well with the findings of preclinical animal studies.6,9 The occurrence of constipation and peripheral neuropathy, the most common and clinically relevant toxicities, may be attributable to the following hypothesized mechanisms. EC145 is metabolized in the liver, and the free DAVLBH enters the gastrointestinal tract via biliary excretion. The exposure of gastrointestinal tissue to free DAVLBH may cause the observed gastrointestinal toxicity. Similarly, it may be speculated that the peripheral neuropathy is secondary to DAVLBH-induced interference with microtubules, thus affecting axonal transport. Logistic regression analysis indicates that the EC145 AUC, but not Cmax, is a significant predictor for the incidence of constipation but not peripheral neuropathy (Figure 3). This supports the clinical observation that the drug-induced toxicity (ie, fast onset ileus/severe constipation) was not a Cmax phenomenon.

A well-tolerated intravenous bolus dose of 2.5 mg was recommended as the phase II trial dose. At the dose of 2.5 mg, intravenous injection resulted in a 3-fold higher Cmax (mean, 129 vs 42 ng/mL) but equivalent AUC (42 vs 40 h*ng/mL) compared to the 1-hour infusion. An intravenous injection was recommended for use in the phase II trial because EC145 Cmax was not associated with the drug-related toxicities (ie, constipation or peripheral neuropathy) and also because optimal folate-targeted therapy might be achieved by maximizing FR loading with the FR conjugate given at a concentration required for FR saturation in a dose-dense manner. The choice of the conjugate-dosing frequency depends, in a large part, on the FR recycling rate in tumors. Previous studies suggest that FR recycling rates can vary among different tumors but generally with a recycling frequency of 12 to 24 hours.11 Maximum tumor-to-normal tissue ratios are generally achieved when a saturating dose is administered at a slightly lower frequency than the frequency of FR recycling in the tumor.11 When significantly subsaturating doses of folate conjugates are administered, optimal tumor targeting can still occur at high dosing frequency.11 Importantly, preclinical studies have demonstrated that EC145 is more efficacious against FR-positive tumors when administered at low but more frequent doses, while it is least effective when given at high and less frequent doses.9 Based on these findings, a dose-dense regimen has been proposed for the ongoing phase II trial, in which the same cumulative dose found to be well tolerated in humans (2.5 mg × 6 doses per month) is divided into smaller doses of 1.0 mg given daily as an intravenous bolus injection (ie, Monday through Friday) for 3 weeks of a 4-week cycle (with a total dose of 15 mg per month). The clinical efficacy of this dense-dosing regimen is yet to be determined.

In conclusion, EC145 pharmacokinetics is characterized by a rapid distribution and elimination in cancer patients. BSA was identified as a statistically significant covariate on EC145 clearance. EC145 clearance and AUC, but not Cmax, were significant predictors for the incidence of constipation, a most common and clinically relevant EC145-induced toxicity. A dose-dense regimen is recommended for phase II trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Endocyte Inc (West Lafayette, Indiana). We thank the patients enrolled in this study.

Financial disclosure: Patrick J. Klein, David Morgenstern, Christopher P. Leamon, and Richard A. Messmann are currently employed at Endocyte Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antony AC. The biological chemistry of folate receptors. Blood. 1992;79(11):2807–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker N, Turk MJ, Westrick E, Lewis JD, Low PS, Leamon CP. Folate receptor expression in carcinomas and normal tissues determined by a quantitative radioligand binding assay. Anal Biochem. 2005;338(2):284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toffoli G, Cernigoi C, Russo A, Gallo A, Bagnoli M, Boiocchi M. Overexpression of folate binding protein in ovarian cancers. Int J Cancer. 1997;74(2):193–198. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970422)74:2<193::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitman SD, Frazier KM, Kamen BA. The folate receptor in central nervous system malignancies of childhood. J Neurooncol. 1994;21(2):107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01052894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross JF, Chaudhuri PK, Ratnam M. Differential regulation of folate receptor isoforms in normal and malignant tissues in vivo and in established cell lines: physiologic and clinical implications. Cancer. 1994;73(9):2432–2443. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2432::aid-cncr2820730929>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leamon CP, Reddy JA, Vlahov IR, et al. Preclinical antitumor activity of a novel folate-targeted dual drug conjugate. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(5):659–667. doi: 10.1021/mp070049c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viola-Villegas N, Rabideau AE, Cesnavicious J, Zubieta J, Doyle RP. Targeting the folate receptor (FR): imaging and cytotoxicity of Rel conjugates in FR-overexpressing cancer cells. Chem Med Chem. 2008;3(9):1387–1394. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leamon CP, Reddy JA, Vlahov IR, et al. Comparative preclinical activity of the folate-targeted Vinca alkaloid conjugates EC140 and EC145. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(7):1585–1592. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy JA, Dorton R, Westrick E, et al. Preclinical evaluation of EC145, a folate-vinca alkaloid conjugate. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4434–4442. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sausville E, LoRusso P, Quinn M, et al. A phase I study of EC145 administered weeks 1 and 3 of a 4-week cycle in patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S):2577. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulos CM, Reddy JA, Leamon CP, Turk MJ, Low PS. Ligand binding and kinetics of folate receptor recycling in vivo: impact on receptormediated drug delivery. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(6):1406–1414. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. Xpose: an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;58(1):51–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(98)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie R, Mathijssen RH, Sparreboom A, Verweij J, Karlsson MO. Clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan and its metabolites in relation with diarrhea. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72(3):265–275. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.126741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Karlsson MO, Brahmer J, et al. CYP3A phenotyping approach to predict systemic exposure to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(23):1714–1723. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlahov IR, Santhapuram HK, Kleindl PJ, Howard SJ, Stanford KM, Leamon CP. Design and regioselective synthesis of a new generation of targeted chemotherapeutics. Part 1: EC145, a folic acid conjugate of desacetylvinblastine monohydrazide. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(19):5093–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leamon CP, Reddy JA, Vlahov IR, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of EC72: a new folate-targeted chemotherapeutic. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(4):803–811. doi: 10.1021/bc049709b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leamon CP, Parker MA, Vlahov IR, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of EC20: a new folate-derived, (99m)Tc-based radiopharmaceutical. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13(6):1200–1210. doi: 10.1021/bc0200430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]