Abstract

Loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells was associated with decreased production of several T-helper 1 (TH1) and TH2 cytokines and increased production of interleukin 17 (IL-17), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), CCL4, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) by CD8+ T cells 21 days after simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in rhesus macaques. Shifting of mucosal TH1 to TH2 or T-cytotoxic 1 (TC1) to TC2 cytokine profiles was not evident. Additionally, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells showed upregulation of macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-basic) cytokines that have been linked to HIV disease progression.

TEXT

Early profound loss of intestinal memory CD4+ T cells is a hallmark of both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection (1–5). Our recent study showed that SIV selectively infects and eliminates dividing, non-SIV-specific “first responder” CD4+ T cells in acute infection (5). Our data also suggest that pathogenic SIVMAC251 infection in rhesus macaques (RMs) induces an increased level of peripheral blood (PB) T-cell activation and proliferation and higher-level expression of several cytokines/chemokines in plasma (6). Understanding cytokine/chemokine networks during acute HIV/SIV infection is important for developing effective vaccines and therapeutics (7). The reduction in the efficacy of T-helper 1 (TH1) cell function in PB during HIV infection has been proposed to occur due to a shift from TH1 to TH2 responses (8–10). However, this is controversial, as additional studies found evidence of a shift toward the TH0 phenotype (11) or no evidence of a shift from the TH1 to the TH2 cytokine profile (12). A shift in CD8+ T-cytotoxic 1 (TC1) to TC2 responses in PB has also been proposed to occur during HIV infection (10, 13). However, these studies are limited to PB, with little data on how cytokine/chemokine profiles in intestinal tissues are affected during acute HIV infection, despite the fact that intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs) are a major site of viral replication and CD4+ T-cell depletion (2, 14, 15). Here, we have compared the profiles of 28 different cytokines/chemokines produced by single-positive (SP) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from jejunum LPLs before and 21 days after SIVMAC251 infection in RMs to assess the dynamics of changes in cytokine/chemokine networks in intestinal tissues.

Five adult female RMs (Macaca mulatta), negative for SIV, HIV-2, type D retrovirus, and simian T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection, were treated with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera; 30 mg intramuscularly) and 4 weeks later inoculated with 500 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of SIVMAC251 intravaginally at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC). Excisional biopsy specimens of jejunum (6 to 10 cm long) were collected before and 21 days after SIV infection under the supervision of TNPRC veterinarians in accordance with the standards incorporated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (44) and with the approval of the Tulane Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All five SIV-infected macaques had high plasma viral loads [log10(6.55) to log10(7.43) viral RNA copies/ml of plasma] 21 days after SIV infection. Jejunum LPLs were isolated both before and 21 days after SIV infection as previously described (3, 16–18). Jejunum LPLs were first labeled with LIVE/DEAD stain (Invitrogen), followed by surface staining with anti-CD3 (SP34.2; BD Biosciences), anti-CD4 (L200; BD Biosciences), anti-CD8 (3B5; Invitrogen), anti-programmed cell death 1 (anti-PD-1) (J105; eBioscience), and anti-CD38 (OKT10; NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). Data were acquired using a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, CA) within 24 h of staining as reported previously (19).

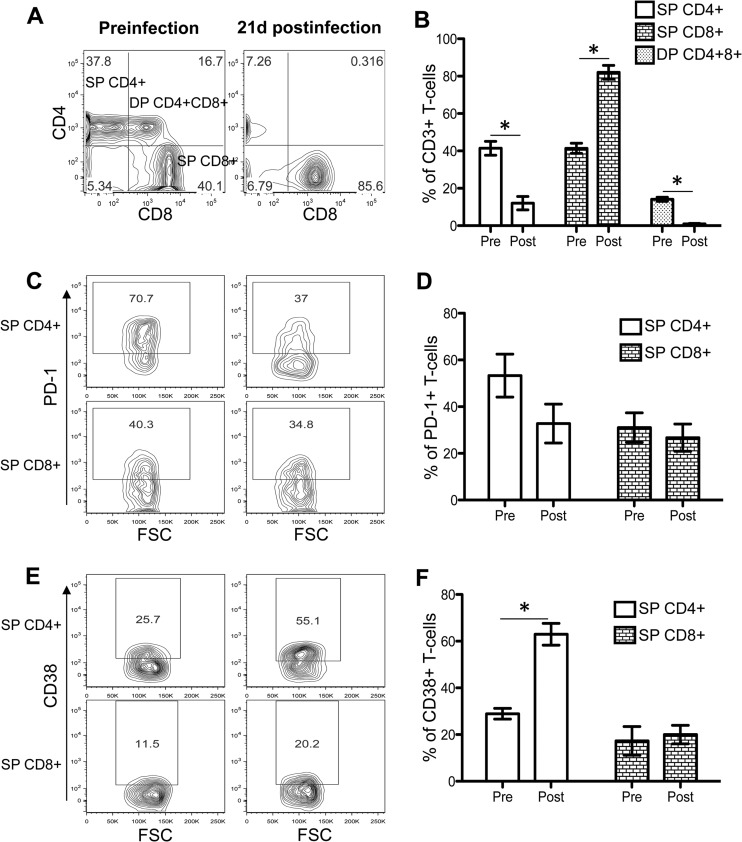

CD4+ T-cell depletion and increased CD38 expression in CD4+ T cells 21 days after SIV infection.

All RMs showed statistically significant reductions in jejunum double-positive (DP) CD4+ CD8+ (14.2% before infection versus 0.9% at 21 days postinfection) and SP CD4+ (41.4% before infection versus 12.0% at 21 days postinfection) T cells 21 days after SIV infection (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A and B). The increased expression of PD-1, a member of the CD28 family, is considered a measure of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell exhaustion (20, 21). In this study, we observed decreased PD-1 expression in SP CD4+ T cells, compared to levels for SP CD8+ T cells during acute infection (Fig. 1C and D). However, PD-1 expression differs by subsets of CD4+ T cells. PD-1 is highly expressed by CCR5+ CD4+ T cells as well as in central memory (CD28+ CD95+) CD4+ T cells (20). We have also previously shown that the majority of the intestinal SP CD4+ T cells are central memory T cells and express a higher percentage of CCR5 coreceptors than PB (16). These populations of CD4+ T cells are rapidly depleted during acute SIV infection, and the remaining cells express lower levels of PD-1. There was a slight decrease in PD-1 expression in SP CD8+ T cells (31.0% preinfection versus 26.7% 21 days after SIV infection) 21 days after SIV infection. However, the differences in PD-1 expression in intestinal CD4+ and CD8+ T cells between the preinfection time point and 21 days after SIV infection are not statistically significant.

Fig 1.

Distribution of single-positive (SP) CD4+ CD8+ and double-positive (DP) CD4+ CD8+ T cells in jejunum LPLs and their expression of phenotypic markers of activation and exhaustion. (A) Representative contour plots showing SP CD4+, CD8+, and DP CD4+ CD8+ T-cell population before and 21 days after SIV infection. Plots were generated by gating CD3+ T cells. (B) Mean percentages (± standard errors [SE]) of SP CD4+, CD8+, and DP CD4+ CD8+ T cells of five SIVMAC251-infected macaques before infection (pre) and 21 days after infection (post). Representative contour plots show PD-1 (C) and CD38 (E) phenotypic expression in SP CD4+ and SP CD8+ T-cell population before and after SIV infection, where cells were gated through CD3+ T cells. Mean percentages (± SE) of T-cell exhaustion (PD-1) (D) and activation (CD38) (F) markers are shown for SP CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of five SIVMAC251-infected macaques before and after SIV infection. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in respective cell populations, compared to preinfection levels (P < 0.05). FSC, forward-angle light scatter.

T-cell activation was also indirectly assessed by CD38 expression on T-cell surfaces. Increased surface expression of CD38 on CD8+ T cells is considered to be an indicator of immune activation and a strong prognostic marker of disease progression and death in HIV-infected patients (22). While we did observe increased expression of CD38 on CD4+ T cells 21 days after SIV infection, compared to preinfection levels (Fig. 1E and F), this was not observed on CD8+ T cells. Using other markers (increased expression of CD25, CD69, and HLA-DR), we have previously shown that intestinal SP CD8+ T cells from normal macaques are highly activated (16). These data raise the question of the utility of CD38 as a marker of immune activation on intestinal CD8+ T cells of rhesus macaques.

Isolation, sorting, and stimulation of jejunum SP CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from jejunum lamina propria.

SP CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were sorted from jejunum LPLs (2.5 × 107 to 5.0 × 107 cells) by use of nonhuman primate magnetic cell separation microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS). In brief, CD20+ B cells were isolated first from jejunum LPLs by positive selection using anti-CD20 MAbs. The unlabeled cells were further sorted by negative selection for either SP CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by use of anti-CD8 or anti-CD4 MACS magnetic cell separation microbeads, respectively, in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. Usage of either anti-CD8 or anti-CD4 microbeads in the first step during cell sorting would also deplete the DP CD4+ CD8+ T-cell population. Between 2.5 × 106 and 10.0 × 106 sorted cells for each population (SP CD4+ and SP CD8+ T cells) were obtained from the jejunum LPLs and were found to be 93 to 96% pure by flow cytometry assays using anti-CD3, -CD4, and -CD8 MAbs (data not shown). Sorted SP CD4+ and SP CD8+ T cells (5 × 105 sorted cells/well) were stimulated with either anti-CD3/28 MAbs (CD3: 6G12, obtained from the NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource, used at 10 μg/ml, or CD28: CD28.2, obtained from BD Biosciences, used at 1 μg/ml) or Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; 2 μg/ml; Toxin Technologies) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 along with the appropriate medium control. For anti-CD3/28 MAb stimulation, plates were first coated overnight at 4°C with anti-CD3 MAbs diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Purified anti-CD28 MAbs were added to the cell culture at the time point of cell stimulation. Cell culture supernatants were collected 72 h after stimulation. The concentrations of cytokines/chemokines in the cell culture supernatants were quantified using a Cytokine Monkey magnetic 28-plex panel (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The 28 analytes detected by this panel are as follows: interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-12, IL-15, IL-17, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1; CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α) (CCL3), MIP-1β (CCL4), RANTES (CCL5), eotaxin (CCL11), macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC; CCL22), monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG; CXCL9), IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10), interferon-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC; CXCL11), epidermal growth factor (EGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-basic), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The multiplex plate was read using the Bio-Plex 200 suspension array Luminex system (Bio-Rad) as reported previously (23). Graphical presentation and statistical analysis of the data were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0f; GraphPad). Eighteen out of 28 cytokines/chemokines had detectable changes in either anti-CD3/28- or SEB-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2 to 4). For the majority of chemokines and cytokines, the responses detected in either anti-CD3/28- or SEB-stimulated cultures were similar; however, SEB-stimulated cultures had lower-level responses. SEB has been used as T-cell superantigen and provides useful information on T-cell signaling pathways. However, SEB stimulation is not always comparable to anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, which is considered to be a more physiologically relevant mode of T-cell activation (24, 25). Cells stimulated with anti-CD3/28 MAbs or SEB did not induce measurable responses for 10 different cytokines/chemokines (IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-4, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, TNF-α, CCL22, EGF, and G-CSF).

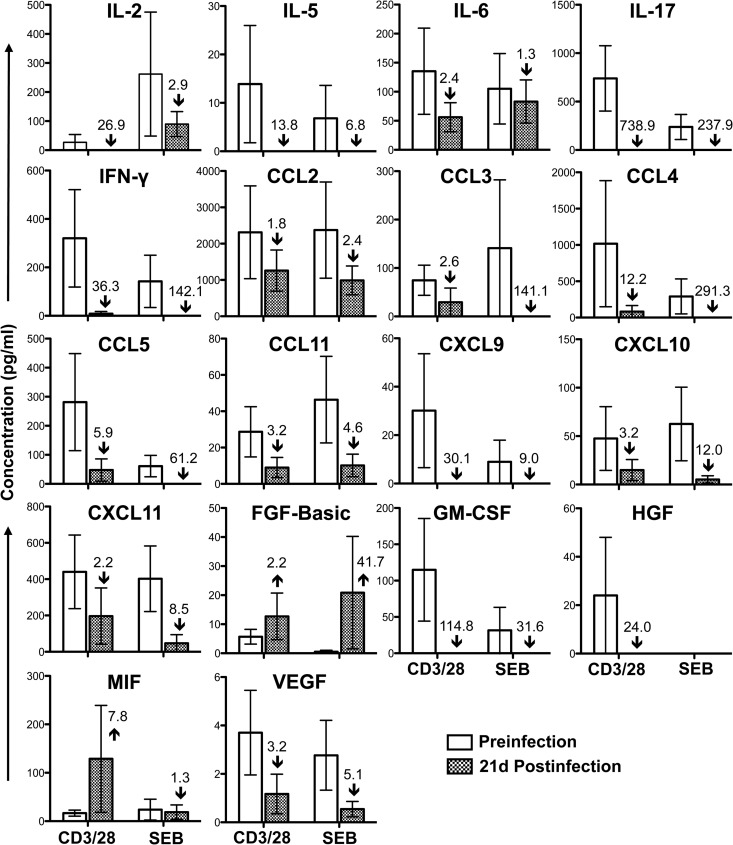

Fig 2.

Cytokine/chemokine profile in jejunum CD3+ CD4+ T cells during acute SIVMAC251 infection. Bar graphs show 18 different cytokine/chemokine measurements taken before and 21 days (21d) after SIV infection from culture supernatants of sorted single-positive CD4+ T cells stimulated with either anti-CD3/CD28 monoclonal antibodies or Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB). Medium control values were subtracted from all values before the analysis (n = 5). The number and arrow in each bar for the postinfection time point show the mean fold increase (upward arrow) or decrease (downward arrow) compared to the preinfection level.

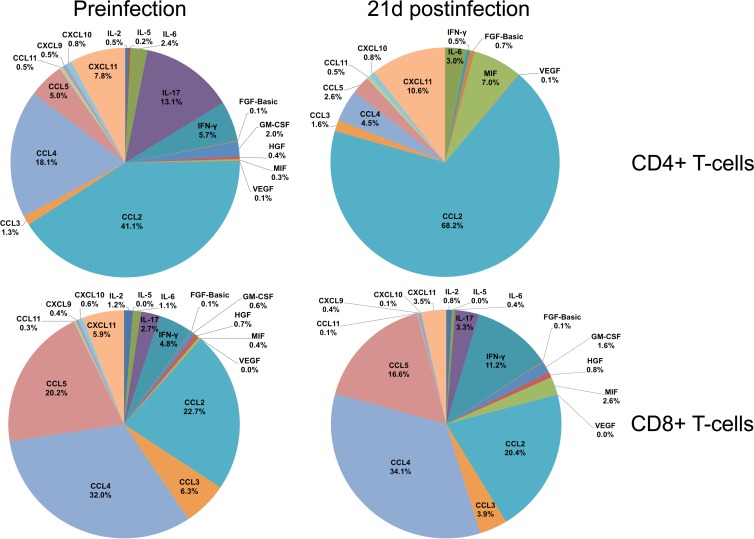

Fig 4.

Relative contribution of cytokine/chemokine expression during acute SIVMAC251 infection. The pie charts illustrate the relative percentage contribution of each cytokine/chemokine from culture supernatants of sorted single-positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 monoclonal antibodies before and 21 days after SIV infection. Medium control values were subtracted from all values before the analysis (n = 5). Note that cytokines having 0.01 to 0.04% overall contribution are represented as 0% in the pie chart.

Cytokine/chemokine responses in CD4+ T cells during acute SIV infection.

The majority of cytokines/chemokines expressed by intestinal SP CD4+ T cells prior to infection were downregulated during acute SIV infection. IL-2 (growth factor), IL-5, IL-6 (proinflammatory cytokine), IL-17, IFN-γ, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, GM-CSF, HGF, and VEGF showed at-least-1.5-fold reductions after infection, suggesting an overall dysfunction of intestinal CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of a shift from TH1 (primarily IFN-γ) to TH2 (primarily IL-5) cytokine responses or vice versa in intestinal SP CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2).

Chemokines (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11) that play major roles in immune activation and recruitment of immune cells, including T cells, granulocytes, and monocytes, were downregulated, which is suggestive of a failing immune response. For example, CXCL9 is associated with immune activation and CD8+ T-cell recruitment (26, 27), and CXCL11 induces recruitment of CD4+ T cells and is an important regulator of HIV pathogenesis (28).

Growth factors, including IL-2, GM-CSF, HGF, and VEGF, were downregulated. IL-2 and GM-CSF were found to play important roles in differentiation and recruitment of immune cells (29). Similarly, HGF and VEGF stimulate vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, besides being associated with HIV neuropathogenesis (30).

However, MIF and FGF-basic cytokines were upregulated by CD4+ T cells during acute infection. The growth factor FGF-basic and proinflammatory cytokine MIF were elevated more than 2-fold and 7-fold, respectively, after stimulation with anti-CD3/28 MAb 21 days after SIV infection, compared to preinfection levels (Fig. 2). FGF-basic modulates normal processes of angiogenesis, wound healing, and tissue repair and has been shown to be elevated in HIV-infected patients and patients with neurological symptoms (31–33). Increased MIF in plasma during acute HIV infection is thought to play an important role in promoting HIV transcription and viral replication (34, 35). In summary, significant loss of LPL CD4+ T cells, substantially decreased production of several TH1 and TH2 cytokines, and an increased production of FGF-basic and MIF proteins are all suggestive of poor prognosis of the intestinal effector function of CD4+ T cells during acute SIV infection (Fig. 1 and 2). However, none of these cytokine responses between the preinfection period and 21 days after SIV infection were found to be statistically significant (P > 0.05) by a 2-tailed paired t test.

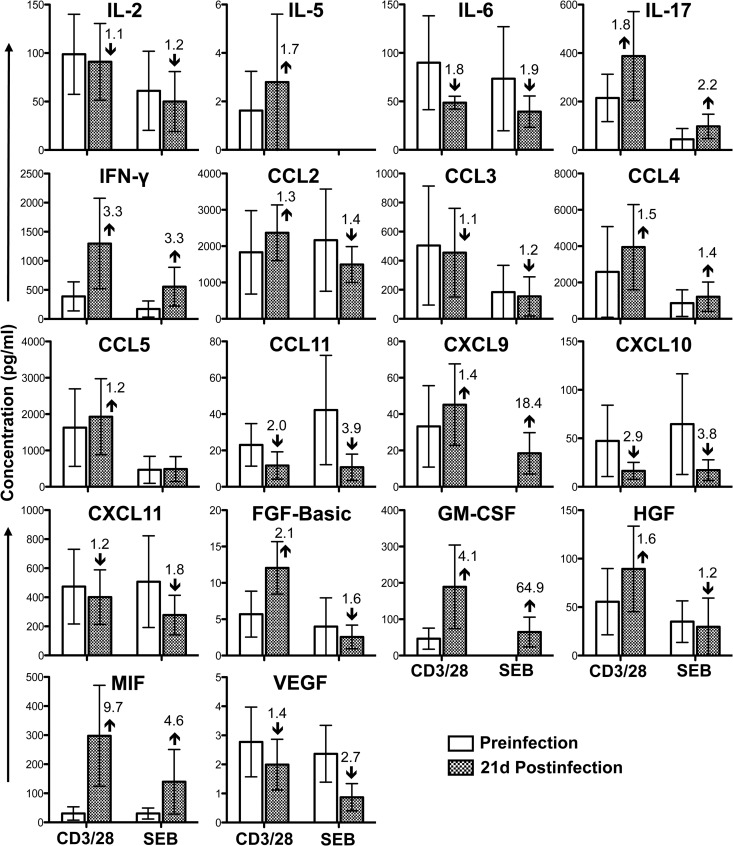

Cytokine/chemokine responses in CD8+ T cells during acute SIV infection.

CD8+ T-lymphocyte cytokine responses were either maintained (IL-2, CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL11, and VEGF; less-than-1.5-fold change in anti-CD3/28 MAb-stimulated cultures, compared to preinfection levels), decreased (IL-6, CCL11, and CXCL10; more-than-1.5-fold reduction in anti-CD3/28 MAb-stimulated cultures, compared to preinfection levels), or increased (IL-5, IL-17, IFN-γ, CCL4, FGF-basic, GM-CSF, HGF, and MIF; more-than-1.5-fold increase in anti-CD3/28 MAb-stimulated cultures, compared to preinfection levels) during acute SIV infection (Fig. 3). These data do not support a shift from TC1 to TC2 in jejunum SP CD8+ T cells, as both IL-5 and IFN-γ cytokine levels increased more than 1.5-fold during acute infection, compared to preinfection levels (Fig. 3). Upregulation of different cytokines/chemokines by CD8+ T cells is indicative of immune activation in CD8+ T cells, despite the absence of surface CD38 expression in this population during acute infection. These data further bring into question the utility of CD38 as a marker of immune activation in intestinal CD8+ T cells in rhesus macaques and warrant further investigation. The increased expression of IL-17 produced by CD8+ T cells also suggests an influx of TC17 cells during acute SIV infection that might play a role in regulating functional immune responses and intestinal homeostasis. IL-17 also plays a vital role in pathogen clearance and mediates proinflammatory responses by inducing the production of several cytokines, including GM-CSF, which was upregulated at least 4-fold from preinfection levels. Additionally, increased IFN-γ expression produced by CD8+ T cells may play an important role in inhibiting HIV pathogenesis (36, 37). However, as with CD4+ T cells, upregulation of MIF is likely to be detrimental to progression of disease (35).

Fig 3.

Cytokine/chemokine profile in jejunum CD3+ CD8+ T cells during acute SIVMAC251 infection. Bar graphs show 18 different cytokine/chemokine measurements taken before and 21 days (21d) after SIV infection from culture supernatants of sorted single-positive CD8+ T cells stimulated with either anti-CD3/CD28 monoclonal antibodies or Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB). Medium control values were subtracted from all values before the analysis (n = 5). The number and arrow in each bar for the postinfection time point show the mean fold increase (upward arrow) or decrease (downward arrow) compared to the preinfection level.

Increased CXCL10 RNA levels in plasma and lymph nodes has been associated with rapid HIV disease progression and viral replication (38–40). CXCL10 also acts as a chemoattractant for monocytes/macrophages, T cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells. However, in this study, intestinal CXCL10 was decreased 2.9- to 3.2-fold in both jejunum CD4+ and CD8+ T cells 21 days after infection, compared to preinfection levels. This occurred despite the increased levels of intestinal IFN-γ and IL-17 produced by CD8+ T cells, which have a role in upregulating CXCL10. This suggests either that the regulation of CXCL10 expression in jejunum differs from that in PB and lymph nodes during SIV/HIV infection or that the major sources of CXCL10 in the intestine are cells other than SP CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

CCL11, which was shown to inhibit HIV replication in vitro (41) and is important in recruitment of eosinophils, was also downregulated during SIV infection in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. However, the chemokine CCL4 was upregulated, and expression of CD8+-specific CCL4 may play an important role in immune response against SIV/HIV by inhibiting SIV/HIV replication and killing of virus-infected cells (36, 37). Three growth factors, namely, FGF-basic, GM-CSF, and HGF, were also upregulated in CD8+ T cells, and as with CD4+ cells, the increase in FGF-basic is indicative of a poor prognosis. Increased levels of HGF during HIV infection are often associated with secondary infection complications such as Kaposi's sarcoma (42). Conversely, GM-CSF is thought to be involved in inducing immune responses by recruiting and stimulating antigen-presenting cells (29) and has been used as a promising adjuvant in HIV vaccine studies (43). In summary, CD8+ showed evidence of upregulation of cytokines, indicating a functional immune response; however, none of these described differences in cytokine responses were found to be statistically significant (P > 0.05) by a 2-tailed paired t test. When the data are displayed by SIV infection time point and T-cell phenotype, the relationship between SIV infection and overall contribution of cytokines/chemokines expression becomes more apparent (Fig. 4). Intestinal CD4+ T cells demonstrated marked reduction of IL-2, IL-17, IFN-γ, CCL4, and CCL5 and increased production of FGF-basic and MIF cytokines/chemokines 21 days after SIV infection, compared to their preinfection levels (Fig. 4). In contrast, marked increases in IL-17, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and MIF cytokines/chemokines in CD8+ T cells were observed 21 days after SIV infection (Fig. 4).

In conclusion, loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells was associated with downregulation of several TH1 and TH2 cytokines in CD4+ T cells during acute SIV infection. In isolated populations of CD4 and CD8+ T cells, no evidence of a TH1-to-TH2 shift for CD4+ T cells or a TC1-to-TC2 shift for CD8+ T cells (or vice versa) was found in gut-associated lymphoid tissue during acute SIV infection. The experimental design does not address cytokine/chemokine changes for other populations or at time points beyond the acute infection period. Decreased CD4+-specific and increased CD8+ T-cell-specific cytokine/chemokine responses suggest that CD8+ T cells are actively mounting functional immune responses and potentially mitigating some of the impact of the loss of functional TH cells. The absence of surface PD-1 expression upregulation suggests that intestinal CD8+ T cells are not exhausted. Despite upregulation of several essential effector cytokines/chemokines (IL-17, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF) by CD8+ T cells, upregulation of FGF-basic, HGF, and MIF chemokines may provide poor prognosis in SIV/HIV infection either by favoring HIV/SIV replication or by other, unknown mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maury Duplantis, Mary Barnes, and all animal care staff of the Division of Veterinary Medicine at the Tulane National Primate Research Center for their technical assistance and Geeta Ramesh for her critical comments on the manuscript.

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P20 GM103458-09 and R21 AI080395 (to B.P.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Chase A, Zhou Y, Siliciano RF. 2006. HIV-1-induced depletion of CD4+ T cells in the gut: mechanism and therapeutic implications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27:4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, Rosenzweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner AA. 1998. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280:427–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Das A, Lackner AA, Veazey RS, Pahar B. 2008. Intestinal double-positive CD4+CD8+ T cells of neonatal rhesus macaques are proliferating, activated memory cells and primary targets for SIVMAC251 infection. Blood 112:4981–4990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Rasmussen T, Pahar B, Poonia B, Alvarez X, Lackner AA, Veazey RS. 2007. Massive infection and loss of CD4+ T cells occurs in the intestinal tract of neonatal rhesus macaques in acute SIV infection. Blood 109:1174–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Xu H, Pahar B, Lackner AA, Veazey RS. 2013. Divergent kinetics of proliferating T cell subsets in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: SIV eliminates the “first responder” CD4+ T cells in primary infection. J. Virol. 87:7032–7038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Wang X, Morici LA, Pahar B, Veazey RS. 2011. Early divergent host responses in SHIVsf162P3 and SIVmac251 infected macaques correlate with control of viremia. PLoS One 6:e17965. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katsikis PD, Mueller YM, Villinger F. 2011. The cytokine network of acute HIV infection: a promising target for vaccines and therapy to reduce viral set-point? PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002055. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clerici M, Hakim FT, Venzon DJ, Blatt S, Hendrix CW, Wynn TA, Shearer GM. 1993. Changes in interleukin-2 and interleukin-4 production in asymptomatic, human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals. J. Clin. Invest. 91:759–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gazzinelli RT, Makino M, Chattopadhyay SK, Snapper CM, Sher A, Hugin AW, Morse HC., III 1992. CD4+ subset regulation in viral infection. Preferential activation of Th2 cells during progression of retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency in mice. J. Immunol. 148:182–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein SA, Dobmeyer JM, Dobmeyer TS, Pape M, Ottmann OG, Helm EB, Hoelzer D, Rossol R. 1997. Demonstration of the Th1 to Th2 cytokine shift during the course of HIV-1 infection using cytoplasmic cytokine detection on single cell level by flow cytometry. AIDS 11:1111–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maggi E, Mazzetti M, Ravina A, Annunziato F, de Carli M, Piccinni MP, Manetti R, Carbonari M, Pesce AM, del Prete G, Romagnani S. 1994. Ability of HIV to promote a TH1 to TH0 shift and to replicate preferentially in TH2 and TH0 cells. Science 265:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graziosi C, Pantaleo G, Gantt KR, Fortin JP, Demarest JF, Cohen OJ, Sekaly RP, Fauci AS. 1994. Lack of evidence for the dichotomy of TH1 and TH2 predominance in HIV-infected individuals. Science 265:248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voth R, Rossol S, Klein K, Hess G, Schutt KH, Schroder HC, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Muller WE. 1990. Differential gene expression of IFN-alpha and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with AIDS related complex and AIDS. J. Immunol. 144:970–975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, Nguyen PL, Khoruts A, Larson M, Haase AT, Douek DC. 2004. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:749–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pahar B, Lackner AA, Piatak M, Jr, Lifson JD, Wang X, Das A, Ling B, Montefiori DC, Veazey RS. 2009. Control of viremia and maintenance of intestinal CD4(+) memory T cells in SHIV(162P3) infected macaques after pathogenic SIV(MAC251) challenge. Virology 387:273–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pahar B, Lackner AA, Veazey RS. 2006. Intestinal double-positive CD4+CD8+ T cells are highly activated memory cells with an increased capacity to produce cytokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan D, Das A, Liu D, Veazey RS, Pahar B. 2012. Isolation and characterization of intestinal epithelial cells from normal and SIV-infected rhesus macaques. PLoS One 7:e30247. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veazey RS, Rosenzweig M, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Johnson RP, Lackner AA. 1997. Characterization of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of normal rhesus macaques. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 82:230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pahar B, Gray WL, Phelps K, Didier ES, deHaro E, Marx PA, Traina-Dorge VL. 2012. Increased cellular immune responses and CD4+ T-cell proliferation correlate with reduced plasma viral load in SIV challenged recombinant simian varicella virus-simian immunodeficiency virus (rSVV-SIV) vaccinated rhesus macaques. Virol. J. 9:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong JJ, Amancha PK, Rogers K, Ansari AA, Villinger F. 2013. Re-evaluation of PD-1 expression by T cells as a marker for immune exhaustion during SIV infection. PLoS One 8:e60186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanjako D, Ssewanyana I, Mayanja-Kizza H, Kiragga A, Colebunders R, Manabe YC, Nabatanzi R, Kamya MR, Cao H. 2011. High T-cell immune activation and immune exhaustion among individuals with suboptimal CD4 recovery after 4 years of antiretroviral therapy in an African cohort. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorgi JV, Liu Z, Hultin LE, Cumberland WG, Hennessey K, Detels R. 1993. Elevated levels of CD38+ CD8+ T cells in HIV infection add to the prognostic value of low CD4+ T cell levels: results of 6 years of follow-up. The Los Angeles Center, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6:904–912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramesh G, Benge S, Pahar B, Philipp MT. 2012. A possible role for inflammation in mediating apoptosis of oligodendrocytes as induced by the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Neuroinflammation 9:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz RH. 1990. A cell culture model for T lymphocyte clonal anergy. Science 248:1349–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang LP, Byun DG, Demeure CE, Vezzio N, Delespesse G. 1995. Default development of cloned human naive CD4 T cells into interleukin-4- and interleukin-5-producing effector cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:3517–3520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamat A, Misra V, Cassol E, Ancuta P, Yan Z, Li C, Morgello S, Gabuzda D. 2012. A plasma biomarker signature of immune activation in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One 7:e30881. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padovan E, Spagnoli GC, Ferrantini M, Heberer M. 2002. IFN-alpha2a induces IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 production in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and enhances their capacity to attract and stimulate CD8+ effector T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:669–676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foley JF, Yu CR, Solow R, Yacobucci M, Peden KW, Farber JM. 2005. Roles for CXC chemokine ligands 10 and 11 in recruiting CD4+ T cells to HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 174:4892–4900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haddad D, Ramprakash J, Sedegah M, Charoenvit Y, Baumgartner R, Kumar S, Hoffman SL, Weiss WR. 2000. Plasmid vaccine expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor attracts infiltrates including immature dendritic cells into injected muscles. J. Immunol. 165:3772–3781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sporer B, Koedel U, Paul R, Eberle J, Arendt G, Pfister HW. 2004. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is increased in serum, but not in cerebrospinal fluid in HIV associated CNS diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75:298–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ascherl G, Sgadari C, Bugarini R, Bogner J, Schatz O, Ensoli B, Sturzl M. 2001. Serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 2 are increased in HIV type 1-infected patients and inversely related to survival probability. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 17:1035–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presta M, Dell'Era P, Mitola S, Moroni E, Ronca R, Rusnati M. 2005. Fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16:159–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanin V, Delbue S, Marcuzzi A, Tavazzi E, Del Savio R, Crovella S, Marchioni E, Ferrante P, Comar M. 2012. Specific protein profile in cerebrospinal fluid from HIV-1-positive cART-treated patients affected by neurological disorders. J. Neurovirol. 18:416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delaloye J, De Bruin IJ, Darling KE, Reymond MK, Sweep FC, Roger T, Calandra T, Cavassini M. 2012. Increased macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) plasma levels in acute HIV-1 infection. Cytokine 60:338–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regis EG, Barreto-de-Souza V, Morgado MG, Bozza MT, Leng L, Bucala R, Bou-Habib DC. 2010. Elevated levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in the plasma of HIV-1-infected patients and in HIV-1-infected cell cultures: a relevant role on viral replication. Virology 399:31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freel SA, Lamoreaux L, Chattopadhyay PK, Saunders K, Zarkowsky D, Overman RG, Ochsenbauer C, Edmonds TG, Kappes JC, Cunningham CK, Denny TN, Weinhold KJ, Ferrari G, Haynes BF, Koup RA, Graham BS, Roederer M, Tomaras GD. 2010. Phenotypic and functional profile of HIV-inhibitory CD8 T cells elicited by natural infection and heterologous prime/boost vaccination. J. Virol. 84:4998–5006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freel SA, Picking RA, Ferrari G, Ding H, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Kirchherr JL, Soderberg KA, Weinhold KJ, Cunningham CK, Denny TN, Crump JA, Cohen MS, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF, Tomaras GD. 2012. Initial HIV-1 antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in acute HIV-1 infection inhibit transmitted/founder virus replication. J. Virol. 86:6835–6846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durudas A, Milush JM, Chen HL, Engram JC, Silvestri G, Sodora DL. 2009. Elevated levels of innate immune modulators in lymph nodes and blood are associated with more-rapid disease progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected monkeys. J. Virol. 83:12229–12240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lane BR, King SR, Bock PJ, Strieter RM, Coffey MJ, Markovitz DM. 2003. The C-X-C chemokine IP-10 stimulates HIV-1 replication. Virology 307:122–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milush JM, Stefano-Cole K, Schmidt K, Durudas A, Pandrea I, Sodora DL. 2007. Mucosal innate immune response associated with a timely humoral immune response and slower disease progression after oral transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus to rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 81:6175–6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath PD, Wu L, Mackay CR, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. 1996. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 85:1135–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier JA, Mariotti M, Albini A, Comi P, Prat M, Comogilio PM, Soria MR. 1996. Over-expression of hepatocyte growth factor in human Kaposi's sarcoma. Int. J. Cancer 65:168–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson HL, Montefiori DC, Villinger F, Robinson JE, Sharma S, Wyatt LS, Earl PL, McClure HM, Moss B, Amara RR. 2006. Studies on GM-CSF DNA as an adjuvant for neutralizing Ab elicited by a DNA/MVA immunodeficiency virus vaccine. Virology 352:285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Research Council 2001. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]