Abstract

While the MerR-like transcriptional regulator BrlR has been demonstrated to contribute to Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm tolerance to antimicrobial agents known as multidrug efflux pump substrates, the role of BrlR in resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAP), which is based on reduced outer membrane susceptibility, is not known. Here, we demonstrate that inactivation of brlR coincided with increased resistance of P. aeruginosa to colistin, while overexpression of brlR resulted in increased susceptibility. brlR expression correlated with reduced transcript abundances of phoP, phoQ, pmrA, pmrB, and arnC. Inactivation of pmrA and pmrB had no effect on the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin, while inactivation of phoP and phoQ rendered biofilms more susceptible than the wild type. The susceptibility phenotype of ΔphoP biofilms to colistin was comparable to that of P. aeruginosa biofilms overexpressing brlR. BrlR was found to directly bind to oprH promoter DNA of the oprH-phoPQ operon. BrlR reciprocally contributed to colistin and tobramycin resistance in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and CF clinical isolates, with overexpression of brlR resulting in increased tobramycin MICs and increased tobramycin resistance but decreased colistin MICs and increased colistin susceptibility. The opposite trend was observed upon brlR inactivation. The difference in susceptibility to colistin and tobramycin was eliminated by combination treatment of biofilms with both antibiotics. Our findings establish BrlR as an unusual member of the MerR family, as it not only functions as a multidrug transport activator, but also acts as a repressor of phoPQ expression, thus suppressing colistin resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen associated with chronic colonization of a variety of different human tissues and medical instruments. The ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms within the airways of individuals with the genetic disease cystic fibrosis (CF) plays an important role in CF-associated chronic infections by allowing the bacteria to withstand host defenses and antimicrobial treatment (1, 2). Biofilms are complex communities of surface-associated microorganisms embedded within a self-produced extracellular matrix (3, 4). Biofilm communities exhibit increased tolerance to antimicrobial agents, often leading to persistent and chronic infections that are difficult to eradicate (5, 6). Overall, biofilms can be up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts (6). Biofilm tolerance is distinct from resistance mechanisms more commonly associated with planktonic cells, such as acquiring resistance through random mutation or uptake of plasmid-borne resistance markers (7, 8). This high-level tolerance observed in biofilms is thought to be multifactorial, requiring a combination of different mechanisms. Mechanisms contributing to high antimicrobial tolerance in biofilms are thought to include reduced metabolic and growth rates compared to planktonic cells (9–11), the presence of dormant persister cells that are not killed by exposure to antibiotics (12), restricted diffusion of certain types of antimicrobial agents into a biofilm (8, 13, 14), starvation-induced growth arrest (15), and the maturity or developmental stage of the biofilm (10, 16).

Recent evidence further suggested that bacteria within microbial communities employ a specific regulatory mechanism to resist the action of antimicrobial agents. Liao et al. demonstrated that in the human pathogen P. aeruginosa, biofilm tolerance is conferred, in part, by BrlR, a member of the MerR family of multidrug efflux pump activators (17, 18). BrlR was found to contribute to the high-level drug tolerance of biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa by affecting the MICs of and recalcitrance to killing by bactericidal antimicrobial agents, including tobramycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and norfloxacin (17). These antibiotics are substrates of multidrug efflux pumps and act by inhibiting either protein synthesis or DNA replication (19). It is thus not surprising that BrlR was recently reported to activate the expression of genes encoding the multidrug efflux pumps MexAB-OprM and MexEF-OprN (18). However, the contribution of BrlR to the tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAP) was not investigated.

The mode of action of CAP is based on the loss of the membrane barrier property (20, 21). Cationic antimicrobial peptides pass across the outer membrane by interacting with negatively charged lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The electrostatic interaction competitively displaces the divalent polyanionic cations and partly neutralizes LPS, leading to outer membrane permeabilization in a process termed self-promoted uptake (21). Once peptides have crossed the lipid bilayers, evidence suggests that the peptides partition into the cytoplasmic membrane through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, causing stress in the lipid bilayer and, ultimately, loss of the barrier property of the membrane (20, 22, 23). Colistin (also called polymyxin E) is a cationic antimicrobial peptide belonging to the polymyxin group of antibiotics (24). Resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides such as colistin can be mediated by the addition of positively charged 4-amino-arabinose to the lipid A moiety of LPS through the action of the arnBCADTEF operon. This modification reduces the negative charge of LPS, thus reducing the interaction between LPS and cationic antimicrobial peptides. In P. aeruginosa, activation of arnBCADTEF expression has been linked to two separate two-component regulatory systems, PhoPQ and PmrAB, which respond to limiting extracellular concentrations of divalent Mg2+ and Ca2+ (25–27). In contrast, peptide-mediated adaptive resistance requires the two-component systems (TCS) ParRS and CprRS, which lead to activation of the LPS modification system upon exposure to a wide range of antimicrobial peptides (28, 29).

Here, we asked whether BrlR contributes to the tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin, a cationic antimicrobial peptide. Inactivation of brlR correlated with increased resistance of biofilm cells to colistin, while overexpression of brlR resulted in increased susceptibility. The phenotype of susceptibility to colistin of P. aeruginosa overexpressing brlR correlated with reduced expression of phoP, phoQ, and arnC and was comparable to that of ΔphoP. Moreover, BrlR was found to directly bind to oprH promoter DNA of the oprH-phoPQ operon. Our findings establish BrlR as an unusual member of the MerR family of multidrug transport activators in that it acts as a repressor of PhoPQ activation and impairs tolerance of P. aeruginosa to colistin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

All the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was used as the parental strain. All planktonic cultures were grown in flasks at 220 rpm and 37°C using Vogel and Bonner citrate minimal medium (VBMM) (30), which contains the equivalent of 1 mM Mg2+ unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 60 μg/ml tetracycline, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 250 μg/ml carbenicillin for P. aeruginosa and 20 μg/ml tetracycline, 20 μg/ml gentamicin, and 50 μg/ml ampicillin for Escherichia coli.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | λ− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Invitrogen Corp. |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB (rB−mB−−) gal dcm rne131 (DE3) | Invitrogen Corp. |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | B. H. Holloway |

| ΔbrlR | PAO1 ΔbrlR (PA4878) | 17 |

| ΔphoP | PAO1 PW3128 phoP-F08::ISlacZ/hah | 59 |

| ΔphoQ | PAO1 PW3131 phoQ-C09::ISlacZ/hah | 59 |

| ΔpmrA | pmrA::xylE-Gmr | 45 |

| ΔpmrB | pmrB::xylE-Gmr | 45 |

| CF 1-2 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | 50 |

| CF 1-2 ΔbrlR | CF 1-2 harboring ΔbrlR (PA4878); Gmr | 17 |

| CF 1-8 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | 50 |

| CF 1-8 ΔbrlR | CF 1-8 harboring ΔbrlR (PA4878); Gmr | 17 |

| CF 1-13 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | 50 |

| CF 1-13 ΔbrlR | CF 1-13 harboring ΔbrlR (PA4878); Gmr | 17 |

| A1 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | This study |

| A2 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | This study |

| A7 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | This study |

| C2 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | This study |

| D5 | P. aeruginosa isolate from CF patient | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJN105 | Arabinose-inducible gene expression vector; pBRR-1 MCS araC-PBAD Gmr | 31 |

| pMJT1 | Arabinose-inducible gene expression vector; pUCP18 MCS araC-PBAD Amp/Carbr | 32 |

| pJN-bdlA-His6V5 | C-terminal His6V5-tagged bdlA cloned into pJN105 at EcoRI/SpeI | 60 |

| pJN-brlR | brlR cloned into pJN105 | 17 |

| pMJT-brlR-His6V5 | C-terminal His6V5-tagged brlR cloned into pMJT1 | 17 |

| pMJT-phoP | phoP cloned into pMJT1 | This study |

| pMJT-phoQ | phoQ cloned into pMJT1 | This study |

Strain construction.

Complementation and overexpression of brlR and phoP were accomplished by inserting the respective genes in the pJN105 (31) or pMJT1 (32) vector under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. The plasmids were introduced into P. aeruginosa via conjugation or electroporation. Insertion was confirmed by PCR and sequencing. The primers used for strain construction are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Planktonic antibiotic susceptibility testing.

To determine the role of BrlR in antimicrobial susceptibility to colistin, P. aeruginosa strains grown planktonicall to exponential phase y in VBMM at 37°C were treated with colistin (30 μg/ml) for 30 min and subsequently homogenized, serially diluted, and spread plated onto LB agar. Viability was determined via CFU counts. Susceptibility is expressed as log reduction.

MIC determination.

The MIC of colistin was determined by performing a series of 2-fold dilutions in LB and VBMM containing 1% arabinose, using 96-well microtiter plates. The method was adapted from that of Andrews (33). Carbenicillin (250 μg/ml) or gentamicin (50 μg/ml) was added for plasmid maintenance. The antibiotic concentrations used ranged from 0.08 to 40 μg/ml for colistin and 0.09 to 100 μg/ml for tobramycin. The inoculum was ∼104 cells per well, and growth inhibition was observed following overnight incubation at 37°C. The MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that yielded no visible growth.

Biofilm formation.

For biofilm antibiotic susceptibility testing, biofilms were grown under flowing conditions in a flow tube reactor system (1 m long, size 13 silicone tubing; flow rate, 0.1 ml/min; Masterflex; Cole Parmer, Inc.) with an inner surface area of 25 cm2 (34–36). Biofilms were grown at 22°C in VBMM. To ensure overexpression of phoP and brlR, the respective strains were grown in the presence of 0.1% arabinose and 10 μg/ml carbenicillin or 2 μg/ml gentamicin.

Biofilm antibiotic susceptibility assays.

Biofilms grown for 1 day under flowing conditions were treated for 2 h under flowing conditions with tobramycin (150 μg/ml) and colistin (100 μg/ml). Higher antibiotic concentrations were used than for planktonic susceptibility assays to account for the known fact that biofilms are more tolerant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts (6, 37, 38). Combination treatment was carried out by treating biofilms with both colistin and tobramycin at the concentrations mentioned above. Following exposure of biofilms to the respective antimicrobial agents, the biofilms were harvested by squeezing the tubing, followed by the extrusion of the cell paste as previously described (39). The resulting suspension was then homogenized, serially diluted, and spread plated onto LB agar. Viability was determined via CFU counts. Susceptibility is expressed as log reduction. Under the conditions tested, a total of 5 × 108 CFU were detected, on average, per biofilm tube reactor following 1 day of biofilm growth prior to treatment (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

qRT-PCR.

Isolation of mRNA and cDNA synthesis was carried out as previously described (36, 40–42). Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the Eppendorf Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) and the KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA), with oligonucleotides listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. mreB was used as a control. The stability of mreB levels was verified by 16S RNA abundance using primers HDA1/HDA2 (43). Relative transcript quantitation was accomplished using the ep realplex software (Eppendorf AG) by first normalizing transcript abundance (based on the threshold cycle [Ct] value) to that of mreB, followed by determining transcript abundance ratios. Melting curve analyses were employed to verify specific single-product amplification.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Assays of BrlR binding to the promoter region of the oprH-phoPQ operon were performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Thermo Scientific), as previously described (44). Briefly, the biotinylated target DNA fragment PoprH (+1 to +206 relative to the translational start site) was amplified using the primer pair oprH-prom-F/oprH-prom-R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). A total of 0.05 pmol of target DNA was incubated for 30 min at room temperature with extracts obtained from P. aeruginosa overexpressing His6V5-tagged BrlR in 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, and 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC) as nonspecific competitor DNA. A total of 1.25 to 10 pmol of His6V5-tagged BrlR (as indicated by immunoblot analysis using purified His6V5-tagged BrlR) was used. Extracts obtained from P. aeruginosa harboring the empty vector (pMJT1) and a ΔbrlR mutant were used as negative controls. DNA gel shift assays were also carried out using extracts obtained from E. coli overexpressing His6V5-tagged BrlR. For specific competition, nonbiotinylated target DNA (0.05 to 0.5 pmol) was used. Samples were separated on a 5% native polyacrylamide-Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel, blotted onto a Hybond nylon membrane, and probed with anti-biotin antibodies, and bands were subsequently visualized according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical analysis.

Student's t test was performed for pairwise comparisons of groups, and multivariate analyses were performed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by an a posteriori test using Sigma Stat software.

RESULTS

Previous findings indicated the MerR-like transcriptional regulator BrlR plays a role in the high-level tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents known to be substrates of multidrug efflux pumps (17). To determine whether BrlR contributes to the tolerance of P. aeruginosa to the cationic antimicrobial peptide colistin, MIC studies were carried out. The MIC is an indicator of the antimicrobial tolerance of a microorganism and is defined by its ability to grow in the presence of an elevated level of an antimicrobial agent.

MICs were determined by 2-fold serial dilutions in VBMM using 96-well microtiter plates and an inoculum of ∼104 cells per well. The lowest antibiotic concentration yielding no visible growth for P. aeruginosa PAO1 was found to be 2.5 μg/ml (Table 2). Overexpression of brlR in P. aeruginosa (PAO1/pMJT-brlR) correlated with a colistin MIC decrease of up to 4-fold, while brlR inactivation rendered P. aeruginosa more tolerant to colistin, as evidenced by a 4-fold increase in the MIC up to 10 μg/ml (Table 2). Consistent with the observation that limiting concentrations of extracellular divalent cations, such as Mg2+, contribute to antimicrobial peptide resistance in P. aeruginosa (26, 45, 46), no difference in the MIC was noted between the wild-type and ΔbrlR strains when VBMM containing high Mg2+ concentrations (20 mM instead of 1 mM Mg2+) was used (data not shown). However, in the presence of high Mg2+ concentrations (20 mM), overexpression of brlR correlated with a 2-fold reduction in the colistin MIC (data not shown). The effect of a lower Mg2+ concentration on the colistin MIC was not tested, as under these conditions (e.g., 10 μM Mg2+), reduced growth rates were observed. The MIC of colistin for P. aeruginosa PAO1 was also determined in LB. The MIC for P. aeruginosa PAO1 was found to be 1.25 μg/ml. Under the conditions tested, inactivation or overexpression of brlR had a less pronounced effect on the colistin MIC than VBMM (Table 2). Compared to that of the wild type, the MIC of colistin for the strain expressing brlR (PAO1/pMJT-brlR) was 2-fold lower. Inactivation of brlR correlated with a 2-fold increase in the colistin MIC in P. aeruginosa (Table 2). While previous reports indicated brlR expression was biofilm specific (17, 18), the observed effect of brlR inactivation on the colistin MIC suggests brlR is expressed under planktonic conditions, with the medium composition (LB or VBMM versus VBMM-20 mM Mg2+) contributing to brlR expression. The findings are in agreement with the detection of brlR transcripts under planktonic conditions by Wurtzel et al. (47) using RNA-Seq.

Table 2.

Overexpression of brlR in planktonic cells correlated with a 2-fold decrease in the MIC for colistin

| Growth medium | MIC (μg/ml) of colistin for strain: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | ΔbrlR | PAO1/pMJT-brlR | ΔphoP | ΔphoQ | |

| LB | 1.25 | 2.5 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63–1.25 |

| VBMM | 2.5 | 5–10 | 0.63–1.25 | 0.63 | 1.25–2.5 |

All strains were grown in VBMM containing 1.0% arabinose or LB medium.

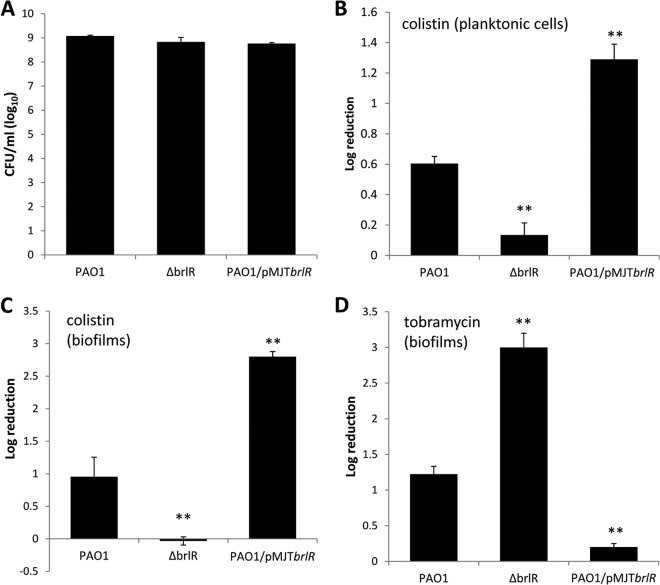

Given the marked difference in MICs between LB medium and VBMM, in particular with respect to differential brlR expression (Table 2), all subsequent experiments were carried out using VBMM. To further explore the role of BrlR in colistin resistance, we next determined the susceptibility to colistin of P. aeruginosa cells grown planktonically to exponential phase. On average, 8.9 × 109 CFU/ml was detected prior to treatment for P. aeruginosa PAO1, the ΔbrlR strain, and a strain overexpressing brlR (Fig. 1A). Inactivation of brlR rendered P. aeruginosa grown planktonically more resistant to colistin (30 μg/ml, equivalent to 10 times the MIC for wild-type PAO1) than the wild type (Fig. 1B). In contrast, overexpression of brlR rendered exponential-phase planktonic cells more susceptible to colistin, as indicated by the increase in log reduction for PAO1/pMJT-brlR compared to PAO1 (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Inactivation of brlR renders biofilms more susceptible to tobramycin but resistant to colistin. (A) Total CFU obtained from P. aeruginosa strains grown to exponential phase in VBMM prior to treatment. (B) Susceptibilities to colistin (30 μg/ml) of exponential-phase-grown P. aeruginosa wild type and strains with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR. Susceptibility was determined by viable counts (CFU) and is expressed as log reduction. (C and D) Susceptibilities of P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms and biofilms of strains with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR to colistin (100 μg/ml) (C) or tobramycin (150 μg/ml) (D). Biofilms were grown in tube reactors for 1 day under flowing conditions using VBMM as the growth medium. The biofilms were treated with colistin or tobramycin for 2 h under flowing conditions. Susceptibility was determined by viable counts (CFU). Experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. The error bars denote standard deviations. **, significantly different from the values for P. aeruginosa PAO1 (P ≤ 0.01).

Considering the effects of brlR inactivation and brlR overexpression on colistin resistance under planktonic growth conditions, we next asked whether BrlR also plays a role in the resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin. As biofilms are more tolerant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts (6, 37, 38), P. aeruginosa wild-type and mutant biofilms with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR were treated longer and with higher concentrations of colistin (40 times the colistin MIC [100 μg/ml] noted for the wild type) than for planktonic susceptibility assays. Treatment of wild-type biofilms with colistin for 2 h resulted in an ∼1-log-unit reduction in viability, while no viability reduction was observed for ΔbrlR mutant biofilms (Fig. 1C). In contrast, overexpression of brlR rendered biofilms significantly more susceptible than wild-type biofilms (Fig. 1C).

The findings suggest that BrlR contributes to colistin resistance of P. aeruginosa, probably by altering the MIC. However, it is interesting that the contribution of BrlR to colistin resistance was opposite to the previously described role of BrlR in the high-level tolerance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents. While inactivation of brlR rendered P. aeruginosa more resistant to colistin, previous results suggested that brlR inactivation coincided with biofilms being more susceptible to bactericidal antibiotics, including tobramycin and norfloxacin (17, 18). Considering that the latter observations were made using LB-grown rather than VBMM-grown biofilms, we next asked whether the different contributions of BrlR to tobramycin resistance in P. aeruginosa are due to differences in the growth media. Similar to previous results (17), however, ΔbrlR mutant biofilms were more susceptible to tobramycin, whereas biofilms overexpressing brlR were more resistant than the wild type (Fig. 1D).

Expression of brlR inversely correlates with expression of arnC, phoP, phoQ, pmrA, and pmrB.

To begin elucidating the mechanism by which BrlR modulates colistin resistance in P. aeruginosa, we asked whether BrlR contributes to the expression of the arnBCADTEF operon (26, 45, 46, 48). Compared to P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms, ΔbrlR mutant biofilms were characterized by a 5.4-fold increase in arnC transcript abundance, while overexpression of brlR correlated with decreased arnC expression, as determined using qRT-PCR (Table 3). In P. aeruginosa, four TCS have been shown to act upon the arn operon, namely, ParRS and CprRS, which are activated upon sensing antimicrobial peptides, and PmrAB and PhoPQ, which respond to limiting extracellular concentrations of divalent Mg2+ and Ca2+ (25–29). qRT-PCR confirmed that inactivation of brlR correlates with increased phoP and phoQ expression compared to wild-type biofilms, while decreased phoP and phoQ transcript abundance was detected in biofilms overexpressing brlR (Table 3). Likewise, expression levels of pmrA and pmrB were upregulated 15- and 28-fold, respectively, in ΔbrlR biofilms compared to wild-type biofilms (Table 3). The findings are in agreement with previous transcriptomic data indicating that brlR inactivation coincides with a 45-fold increase in arnC expression in biofilms and correlates with increased expression of phoP and phoQ, as well as pmrA and pmrB, compared to the wild-type biofilms (18). As no difference in parR, parS, cprR, and cprS expression was noted upon brlR inactivation by transcriptomic analysis (18), these systems were not pursued further. Our findings indicate that BrlR contributes to the repression of arnC, phoP, phoQ, pmrA, and pmrB transcript abundance, with absence of BrlR coinciding with increased transcript levels.

Table 3.

Fold change in transcript levels of genes linked to colistin resistance relative to PAO1 biofilms

| Strain | Fold change in transcript levels relative to PAO1 biofilmsa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| arnC | phoP | phoQ | pmrA | pmrB | |

| ΔbrlR | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ± 0.8 | 27.8 ± 2.2 |

| PAO1/pMJT-brlR | −1.75 ± 0.1 | −2.1 ± 0.2 | −2.8 ± 0.1 | −1.6 ± 0.06 | −1.6 ± 0.06 |

All the strains were grown as biofilms, and qRT-PCR analysis was carried out in triplicate. Standard deviations are indicated.

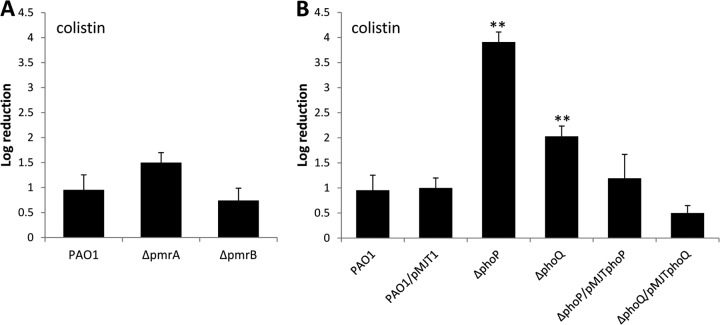

Inactivation of phoP and phoQ renders P. aeruginosa biofilms susceptible to colistin.

To determine whether PmrAB and PhoPQ contribute to the observed resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin in a BrlR-dependent manner, we next tested the susceptibilities of mutant biofilms with phoP, phoQ, pmrA, and pmrB inactivated to colistin using 40 times the MIC. It is interesting that phoP and phoQ are included in an operon with oprH. Macfarlane et al. (48) previously demonstrated that OprH does not contribute to colistin resistance, and therefore, we did not test an oprH mutant. Compared to wild-type biofilms, no significant difference in viability was noted in ΔpmrA and ΔpmrB mutant biofilms (Fig. 2A). The finding suggested that at the colistin concentration tested, the TCS PmrAB likely plays no role in the resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin. In contrast, inactivation of phoP rendered biofilms significantly more susceptible to colistin than wild-type biofilms (Fig. 2B). The susceptibility of ΔphoP mutant biofilms to colistin was comparable to the log reduction observed for biofilms overexpressing brlR (Fig. 1C). While the biofilm architecture of phoP mutant biofilms differed from that of wild-type biofilms (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the supplemental material), no significant difference in the biofilm CFU between wild-type and phoP mutant biofilms was noted (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Complementation of ΔphoP mutant biofilms with phoP restored the resistance phenotype to wild-type levels (Fig. 2B). Moreover, ΔphoQ mutant biofilms were more susceptible to colistin than the wild type but were less susceptible than ΔphoP mutant biofilms (Fig. 2B). The resistance of ΔphoQ to colistin was restored to wild-type levels by complementation with phoQ (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

Inactivation of phoP and phoQ, but not pmrA or pmrB, renders biofilms more susceptible to colistin. Biofilms grown for 1 day in biofilm tube reactors were treated for 2 h with colistin (100 μg/ml) under flowing conditions. Susceptibility was determined by viable counts (CFU). (A) Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms and biofilms of strains with pmrA and pmrB inactivated to colistin (100 μg/ml). (B) Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms, ΔphoP and ΔphoQ biofilms, and mutant biofilms complemented with phoP and phoQ in trans to colistin. Experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. The error bars denote standard deviations. **, significantly different from the values for P. aeruginosa PAO1 (P ≤ 0.01).

The observed difference in susceptibility to colistin between ΔphoP and ΔphoQ mutant biofilms was also apparent in the MIC assays (Table 2). While the MICs for a ΔphoP mutant strain showed a 2-fold decrease in the colistin MIC in LB medium and up to a 6-fold decrease in VBMM compared to the wild type, inactivation of phoQ only correlated with a 2-fold reduction in the colistin MIC.

BrlR binds to the promoter region of the oprH-phoPQ operon.

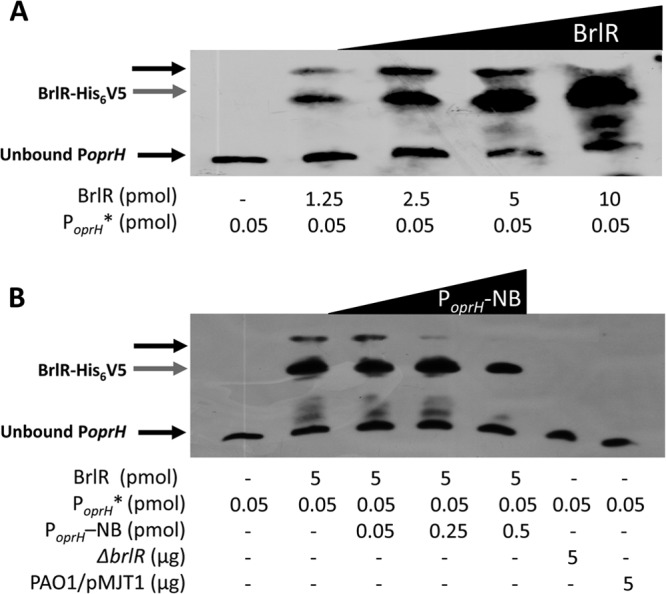

Our findings suggested PhoPQ, but not PmrAB, contributes to the resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin, with inactivation of phoP rendering biofilms as susceptible to colistin as brlR overexpression (Fig. 1C and 2B). Taking into account that multicopy expression of brlR coincided with reduced transcript abundances of phoP and phoQ and the PhoPQ-dependent gene arnC (Table 3), we hypothesized that BrlR is either directly or indirectly involved in repression of these transcripts. To determine whether the phoPQ operon is a direct target of BrlR, electrophoretic mobility shift assays were carried out using His6V5-tagged BrlR (BrlR-His6V5) and biotinylated promoter DNA, as previously described (18). BrlR DNA binding was dependent on both the BrlR and oprH promoter DNA concentrations. When the molar concentrations of BrlR were increased, binding to PoprH increased (Fig. 3A). When increasing amounts of the unlabeled specific competitor PoprH fragment were added to the gel mobility shift assay mixture, decreased BrlR binding to the labeled fragment was observed (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained when E. coli extracts overexpressing His6V5-tagged BrlR were used (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These results indicated that BrlR binds to the promoter region of the oprH-phoPQ operon. Taken together with the gene expression results, our findings indicate that BrlR is involved in transcriptional regulation of the oprH-phoPQ operon, acting as a repressor.

Fig 3.

BrlR binds to the promoter of the oprH-phoPQ operon. Shown are DNA gel mobility shift assays using cell extracts obtained from P. aeruginosa expressing His6V5-tagged BrlR (PAO1/pMJT-brlR-His6V5) in trans. Both the concentration of His6V5-tagged BrlR (1.25 to 10 pmol) (A) and the concentration of unlabeled competitor DNA (PoprH -NB; 0 to 0.5 pmol) (B) were varied. Cell extracts obtained from P. aeruginosa harboring the empty vector (PAO1/pMJT1) and a ΔbrlR mutant were used as negative controls. The PoprH DNA fragment is 208 bp long, and 0.05 pmol of the biotinylated DNA fragment was used (PoprH *). BrlR binding to PoprH was detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-biotin antibodies. The band for unbound PoprH is visible at the bottom of each image. The gray arrows indicate unbound His6V5-tagged BrlR. The black arrows near the top of the image indicate shifts. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and representative images are shown.

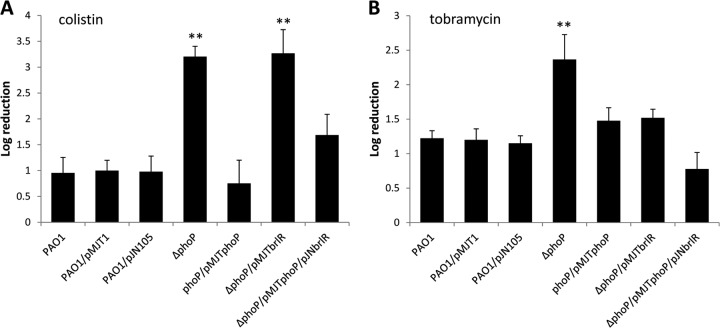

BrlR contributes to colistin resistance through PhoPQ.

We next hypothesized that if BrlR acted upon colistin resistance only through PhoPQ, expression of brlR in a ΔphoP mutant would not render the mutant more susceptible. To address this question, we generated a ΔphoP mutant strain overexpressing brlR. While complementation of the ΔphoP strain with phoP restored the resistance phenotype of ΔphoP biofilms to wild-type levels, multicopy expression of brlR in did not render ΔphoP biofilms more susceptible to colistin (Fig. 4A). Moreover, brlR expression did not significantly alter the biofilm architecture of ΔphoP biofilms (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). However, plasmid-borne expression of both brlR and phoP resulted in reduced susceptibility of ΔphoP/pMJTphoP/pJNbrlR biofilms compared to ΔphoP (Fig. 4A). No difference in susceptibility was noted for the vector controls (Fig. 4A). The findings indicated that BrlR-dependent susceptibility to colistin of P. aeruginosa biofilms required PhoP. While multicopy expression of brlR in the ΔphoP strain did not alter the susceptibility of ΔphoP biofilms to colistin, ΔphoP biofilms overexpressing brlR were more resistant to tobramycin than ΔphoP biofilms (Fig. 4B). Our data are in agreement with previous reports indicating a role of PhoPQ in aminoglycoside resistance under planktonic growth conditions (25, 49). Complementation restored the resistance phenotype of the ΔphoP strain to wild-type biofilm levels (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained for ΔphoP biofilms coexpressing phoP and brlR (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Expression of brlR in ΔphoP mutant biofilms has no effect on resistance to colistin. Biofilms of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and ΔphoP and complemented ΔphoP mutant strains (ΔphoP/pMJTphoP and ΔphoP/pMJTphoP/pJNbrlR) were grown in VBMM for 1 day under flowing conditions and subsequently treated with colistin (100 μg/ml) (A) and tobramycin (150 μg/ml) (B). Susceptibility was determined by viable counts (CFU). Experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. The error bars denote standard deviations. **, significantly different from the values for P. aeruginosa PAO1 (P ≤ 0.01).

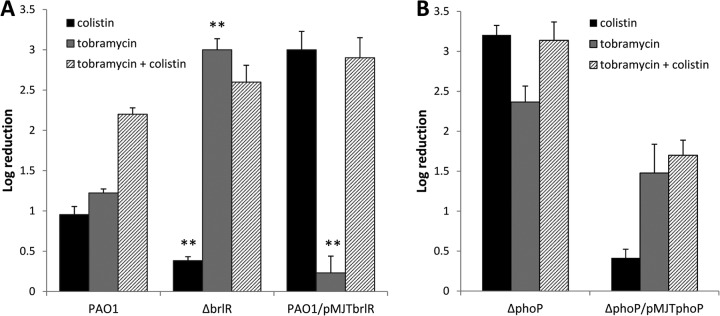

BrlR contributes to colistin and tobramycin resistance in a reciprocal manner.

Overall, our findings strongly support a dual nature of BrlR with respect to biofilm resistance, as overexpression of brlR resulted in enhanced susceptibility to colistin but reduced susceptibility to tobramycin (and the opposite upon brlR inactivation). Considering the reciprocal contribution of BrlR to colistin and tobramycin resistance, we next hypothesized that P. aeruginosa biofilms are equally susceptible to dual treatment with colistin and tobramycin regardless of the level of brlR expression.

Biofilms overexpressing brlR were equally susceptible to colistin alone and colistin together with tobramycin but resistant to tobramycin alone (Fig. 5A). Similarly, combination treatment rendered ΔbrlR biofilms significantly more susceptible than did treatment with colistin alone (Fig. 5A). The susceptibility to colistin and tobramycin noted for ΔbrlR biofilms was comparable to that observed following tobramycin treatment. Moreover, treatment with both antibiotics had an additive effect for P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms, which were found to be overall more susceptible to tobramycin and colistin than to treatment with either antibiotic alone (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained for complemented ΔphoP mutant biofilms (Fig. 5B). In contrast, however, no significant difference in susceptibility was noted when ΔphoP mutant biofilms were treated with either colistin or tobramycin alone or in combination (Fig. 5B). Our data suggested that while differential brlR expression affected the resistance of P. aeruginosa when treated with colistin or tobramycin alone, dual treatment with colistin and tobramycin alleviated the effect of brlR expression levels on resistance and resulted in superior killing of P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms. Moreover, our findings indicate that enhanced killing observed upon dual treatment is based on the differential expression of brlR, but not phoP.

Fig 5.

BrlR contributes to the resistance to colistin and tobramycin by P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms in a reciprocal manner. The susceptibilities of P. aeruginosa wild-type biofilms and biofilms with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR to 100 μg/ml colistin, 150 μg/ml tobramycin, or a combination of 150 μg/ml tobramycin and 100 μg/ml colistin were determined. One-day-old biofilms were treated for 2 h under flowing conditions. **, significantly different from the values for P. aeruginosa PAO1 under the same treatment (P ≤ 0.01). (B) Susceptibilities of ΔphoP biofilms and ΔphoP/pMJT-phoP biofilms following exposure to 100 μg/ml colistin, 150 μg/ml tobramycin, or a combination of 150 μg/ml tobramycin and 100 μg/ml colistin for 2 h under flowing conditions. The experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. The error bars denote standard deviations.

Expression of brlR renders CF clinical isolates more susceptible to colistin but more resistant to tobramycin.

To further explore the reciprocal contribution of BrlR to colistin and tobramycin resistance, we made use of two sets of clinical isolates, with each set originating from a single cystic fibrosis patient. Set 1 comprised isolates A1, A2, A7, C2, and D5, while set 2 comprised isolates CF 1-2, CF 1-8, and CF 1-13. Analysis of the three cystic fibrosis isolates by Southern blotting using a 741-bp PstI-NruI fragment, derived from the upstream region of exotoxin A, demonstrated that the three isolates originated from the same parental strain (50). Whether the isolates comprising set 1 are derived from the same parental strain is unknown. However, numerous studies have shown that isolates obtained from an individual cystic fibrosis patient typically originate from a single parental strain (51–54), and it is therefore likely that the set 1 isolates are clonal. It is interesting that native brlR expression in these clinical isolates grown under surface-associated conditions was comparable to brlR transcript levels observed in P. aeruginosa biofilms as determined using qRT-PCR (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The only exceptions were isolates CF 1-2 and CF 1-13, which were previously shown to have 4- and 8-fold-increased brlR transcript levels, respectively, compared to wild-type biofilms (17) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). We next conjugated the plasmid pJN-brlR into each clinical isolate and subsequently determined the MICs of colistin and tobramycin for clinical isolates and clinical isolates expressing brlR from P. aeruginosa PAO1. A total of 8 clinical isolates were thus tested. As shown in Table 4, the MICs for colistin and tobramycin varied significantly among the clinical isolates tested. For instance, isolate C2 was found to have a colistin MIC of 40 μg/ml and a tobramycin MIC of 12.5 μg/ml, while isolate D5 was characterized by lower MICs of both, 0.625 μg/ml for colistin and 3.125 μg/ml for tobramycin. However, while the MICs differed significantly among the clinical isolates tested, a shift in the MICs upon plasmid-borne expression of brlR was observed in each of the clinical isolates. For clinical isolate C2, expression of brlR resulted in a 6-fold decrease in the MIC for colistin but a 4-fold increase in the MIC for tobramycin. For isolate D5, the colistin-MIC decreased 4-fold while the tobramycin-MIC increased 8-fold. Similar changes in the MIC were observed for all other clinical isolates tested, with brlR expression resulting in a decreased colistin MIC but an increased tobramycin MIC (Table 4).

Table 4.

MICs of colistin and tobramycin for clinical isolatesa

| Clinical isolateb | MIC (μg/ml) of colistin |

MIC (μg/ml) of tobramycin |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | pMJT-brlR | ΔbrlR | - | pMJT-brlR | ΔbrlR | |

| A1 | 5 | 2.5 | 6.25 | 25 | ||

| A2 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 6.25 | 50 | ||

| A7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 12.5 | 25 | ||

| C2 | ≥40 | 5 | 12.5 | 50 | ||

| D5 | 0.6 | 0.15 | 3.1 | 50 | ||

| CF 1-2 | 2.5 | 0.3–0.6 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 1.56 |

| CF 1-8 | 1.25 | 0.6 | 1.25 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 1.56 |

| CF 1-13 | 20 | 0.6 | ≥40 | 50 | ≥100 | 1.56 |

Multicopy expression of brlR resulted in a decrease in the colistin MIC but an increased tobramycin MIC for cystic fibrosis clinical isolates, while inactivation of brlR coincided with an increased colistin MIC but a decreased tobramycin MIC. MIC assays were carried out using LB. The values are based on a minimum of three experiments.

CF isolates A1, A2, A7, C2, and D5 were obtained from P. Singh; strains CF 1-2, 1-8, and 1-13 were originally described by Ogle et al. (50).

We also determined whether inactivation of brlR in a subset of clinical isolates correlated with a reciprocal shift in the MIC. To do so, we made use of three clinical isolates, namely, CF 1-2, CF 1-8, and CF 1-13. With the exception of CF 1-8, isolates with brlR inactivated demonstrated increased colistin MICs but decreased tobramycin MICs compared to the isogenic parental strains (Table 4). It is interesting that isolate CF 1-8 was shown to possess a nonsense mutation in the brlR gene, resulting in a truncated protein (17). The finding that brlR inactivation in CF 1-8 did not affect the MIC compared to the isogenic parental strain indicated that the truncation rendered BrlR nonfunctional. Our data suggest that BrlR contributes in a reciprocal manner to the tolerance to colistin and tobramycin, with BrlR conferring tolerance to tobramycin while rendering P. aeruginosa susceptible to colistin (and the opposite upon brlR inactivation).

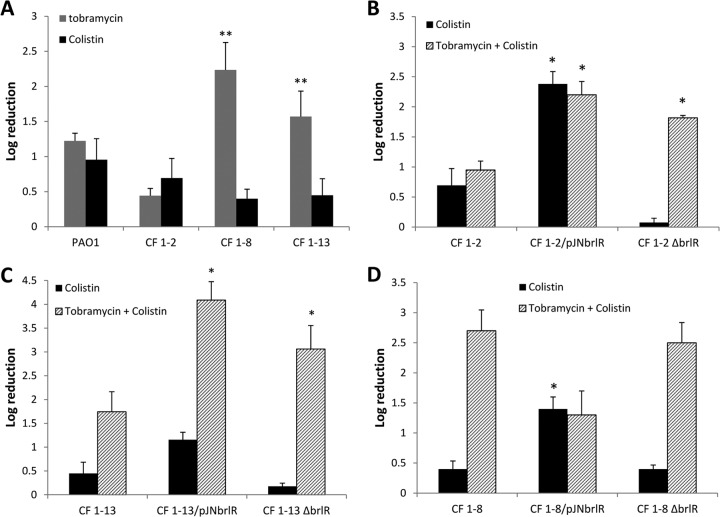

To further explore whether differential expression of brlR from P. aeruginosa and its reciprocal contribution to colistin and tobramycin resistance can be overcome by combination treatment in clinical isolates, biofilms formed by isolates CF 1-2, CF 1-8, and CF 1-13 and isogenic mutant strains with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR were treated with tobramycin, colistin, and a combination of colistin and tobramycin. Susceptibility was determined by viability assays. Biofilms formed by isolates CF 1-2 and CF 1-13 were as resistant to tobramycin and colistin as P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Fig. 6A). Combination treatment had little effect on the susceptibility of CF 1-2 and CF 1-13 biofilms compared to treatment with either antibiotic alone (Fig. 6B and C). Inactivation of brlR in isolate CF 1-2 correlated with reduced killing by colistin relative to the parental strain (Fig. 6B). Dual treatment of CF 1-2 ΔbrlR rendered biofilms of the isolate significantly more susceptible than did treatment with colistin alone. In contrast, brlR overexpression resulted in isolate CF 1-2 being more susceptible to colistin and combination treatment than the parental strain (Fig. 6B). Overall, dual treatment of CF 1-2 with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR was more effective than treatment of the parental strain (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained for isolate CF 1-13 with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR compared to the parental strain (Fig. 6C). The reciprocal contribution of BrlR to colistin and tobramycin resistance was less pronounced in biofilms formed by clinical isolate CF 1-8, likely because CF 1-8 harbors a nonsense mutation in the brlR gene (17). Thus, biofilms of CF 1-8 and CF 1-8 ΔbrlR were found to be equally susceptible to colistin but significantly more susceptible to tobramycin than P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms (Fig. 6A and D). However, similar to multicopy expression of brlR in CF 1-2 and CF 1-13, overexpression of brlR in CF 1-8 biofilms rendered the strain more susceptible to colistin than the parental strain, while combination treatment had an intermediate effect on antibiotic susceptibility (Fig. 6C). These observations are in agreement with the MIC data obtained for this isolate (Table 4).

Fig 6.

BrlR contributes to resistance to colistin and tobramycin by P. aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates in a reciprocal manner. (A) Susceptibility determination of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and clinical CF isolates CF 1-2, CF 1-8, and CF 1-13 grown as biofilms (1 day). The biofilms were treated with 150 μg/ml tobramycin or 100 μg/ml colistin for 2 h under flowing conditions. **, significantly different (P ≤ 0.01) from PAO1. (B to D) Determination of susceptibilities of 1-day-old biofilms formed by isolates CF 1-2, CF 1-8, and CF 1-13 and isogenic strains with brlR inactivated or overexpressing brlR. The biofilms were treated with 100 μg/ml colistin or a combination of 150 μg/ml tobramycin and 100 μg/ml colistin for 2 h under flowing conditions. *, significantly different from the values for the parental strain (P ≤ 0.01). Experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. The error bars denote standard deviations.

Taken together, the data strongly support a role of BrlR in reciprocally contributing to biofilm susceptibility to colistin and tobramycin, with dual treatment overcoming the difference in susceptibility due to differential brlR expression.

DISCUSSION

A hallmark of biofilms is their profound tolerance to antimicrobial agents. In addition to previously described mechanisms contributing to the antibiotic tolerance of biofilms, including slow growth and diffusion limitation, P. aeruginosa biofilms also employ a specific regulatory mechanism involving the transcriptional regulator BrlR to resist the action of antimicrobial agents known to be multidrug efflux pump substrates (17). In particular, BrlR has been demonstrated to contribute to biofilm tolerance to norfloxacin, tobramycin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and trimethoprim by activating the expression of at least two multidrug resistance pumps, thus affecting the MIC and recalcitrance to killing by bactericidal antimicrobial agents (17, 18). However, the protective role of BrlR appears to be absent in P. aeruginosa biofilms with respect to the cationic antimicrobial peptide colistin. Instead, overexpression of brlR resulted in increased susceptibility to colistin, with BrlR acting as a repressor of phoPQ expression while inactivation of brlR made these mutants substantially more resistant. Expression of the phoPQ operon is activated in response to limiting extracellular concentrations of divalent Mg2+ and Ca2+ (25–27) and, outside of autoregulation of the oprH-phoPQ operon by PhoP itself (26), little is known about the regulation of this TCS. The finding that BrlR functions as a repressor of phoPQ gene expression provides a novel level of control of the regulation of the PhoPQ TCS. The PhoPQ system in P. aeruginosa is unique compared to more thoroughly characterized homologs. Unlike the Salmonella PhoPQ system, which directly or indirectly regulates over 200 genes, the P. aeruginosa PhoPQ regulon comprises fewer than 20 genes (26, 55). Moreover, while the Salmonella PhoPQ acts through PmrAB to regulate downstream gene expression, evidence suggests that in P. aeruginosa, PmrAB activation is independent of PhoPQ (26, 56), and both PhoPQ and PmrAB activate the expression of the arnBCADTEF operon responsible for the addition of 4-amino-arabinose to LPS (26, 45). However, under the conditions tested, no evidence of PmrAB contributing to the resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilms to colistin was noted in this study. Instead, only PhoPQ was found to be required for biofilm resistance to colistin. To our knowledge, this is the first description of PhoPQ mediating colistin resistance in P. aeruginosa biofilms. Thus, while PmrAB likely acts independently of PhoPQ under planktonic conditions, our observations suggest that under biofilm growth conditions, PmrAB either plays no role in colistin resistance or, alternatively, that PhoPQ and PmrAB do not act independently in P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides, including colistin, are frequently used in the treatment of pulmonary lung infections in CF patients colonized by P. aeruginosa (57). Previous findings suggested colistin-tobramycin combination treatments result in increased killing of P. aeruginosa biofilms compared to treatment with either antibiotic alone (58). Here, we likewise observed enhanced killing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms and biofilms of clinical isolates CF 1-2 and CF 1-13 upon dual treatment compared to monotherapy. While it is unclear why BrlR would directly or indirectly repress genes responsible for resistance to antimicrobials such as colistin while contributing to tolerance to antibiotics that are multidrug efflux pump substrates (17, 18), the reciprocal role of BrlR in repressing colistin resistance while enhancing resistance to tobramycin provides a genetic basis for the superior killing by tobramycin and colistin when used in combination.

In summary, we demonstrate that in P. aeruginosa, resistance to the cationic antimicrobial peptide colistin is reciprocally regulated by PhoPQ and the transcriptional regulator BrlR. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that BrlR is an unusual member of the MerR family of multidrug efflux pump activators. While members of this family have been demonstrated to function solely as activators, BrlR functions as both an activator of muldtidrug efflux pump genes (18) and a repressor of PhoPQ activation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. E. W. Hancock at the University of British Columbia for providing ΔpmrA and ΔpmrB mutant strains and P. Singh at the University of Washington for providing cystic fibrosis clinical isolates.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI080710).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00834-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donlan RM, Costerton JW. 2002. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:167–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner VE, Iglewski BH. 2008. P. aeruginosa biofilms in CF infection. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 35:124–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey ME, O'Toole GA. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsek MR, Singh PK. 2003. Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:677–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart PS, Costerton JW. 2001. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet 358:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drenkard E. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microbes Infect. 5:1213–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert P, Collier PJ, Brown MR. 1990. Influence of growth rate on susceptibility to antimicrobial agents: biofilms, cell cycle, dormancy, and stringent response. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10:1865–1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anwar H, Strap JL, Chen K, Costerton JW. 1992. Dynamic interactions of biofilms of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa with tobramycin and piperacillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1208–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderl JN, Zahller J, Roe F, Stewart PS. 2003. Role of nutrient limitation and stationary-phase existence in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1251–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keren I, Kaldalu N, Spoering A, Wang Y, Lewis K. 2004. Persister cells and tolerance to antimicrobials. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campanac C, Pineau L, Payard A, Baziard-Mouysset G, Roques C. 2002. Interactions between biocide cationic agents and bacterial biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1469–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderl JN, Franklin MJ, Stewart PS. 2000. Role of antibiotic penetration limitation in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1818–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, McKay G, Siehnel R, Schafhauser J, Wang Y, Britigan BE, Singh PK. 2011. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334:982–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connell JL, Wessel AK, Parsek MR, Ellington AD, Whiteley M, Shear JB. 2010. Probing prokaryotic social behaviors with bacterial “lobster traps”. mBio 1:e00202–10. 10.1128/mBio.00202-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao J, Sauer K. 2012. The MerR-like transcriptional regulator BrlR contributes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 194:4823–4836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao J, Schurr MJ, Sauer K. 2013. The MerR-like regulator BrlR confers biofilm tolerance by activating multidrug-efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 195:3352–3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Nishino T. 2000. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3322–3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock RE, Rozek A. 2002. Role of membranes in the activities of antimicrobial cationic peptides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hancock R. 1997. Peptide antibiotics. Lancet 349:418–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Fujii N, Miyajima K, Yamada K-I, Kirino Y, Anzai K. 1997. Membrane permeabilization mechanisms of a cyclic antimicrobial peptide, tachyplesin I, and its linear analog. Biochemistry 36:9799–9806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Harada M, Fujii N, Miyajima K. 1997. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, with outer and inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1327:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK, Saravolatz LD. 2005. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1333–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macfarlane ELA, Kwasnicka A, Ochs MM, Hancock REW. 1999. PhoP-PhoQ homologues in Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulate expression of the outer-membrane protein OprH and polymyxin B resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 34:305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McPhee JB, Bains M, Winsor G, Lewenza S, Kwasnicka A, Brazas MD, Brinkman FSL, Hancock REW. 2006. Contribution of the PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB two-component regulatory systems to Mg2+-induced gene regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188:3995–4006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moskowitz S, Ernst R, Miller S. 2004. PmrAB, a two-component regulatory system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that modulates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and addition of aminoarabinose to lipid A. J. Bacteriol. 186:575–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández L, Jenssen H, Bains M, Wiegand I, Gooderham WJ, Hancock REW. 2012. The two-component system CprRS senses cationic peptides and triggers adaptive resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independently of ParRS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:6212–6222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández L, Gooderham WJ, Bains M, McPhee JB, Wiegand I, Hancock REW. 2010. Adaptive resistance to the “Last Hope” antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by the novel two-component regulatory system ParR-ParS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3372–3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweizer HP. 1991. The agmR gene, an environmentally responsive gene, complements defective glpR, which encodes the putative activator for glycerol metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 173:6798–6806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman JR, Fuqua C. 1999. Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the arabinose-inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene 227:197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneko Y, Thoendel M, Olakanmi O, Britigan BE, Singh PK. 2007. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J. Clin. Invest. 117:877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews JM. 2001. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:5–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauer K, Camper AK, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Davies DG. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 184:1140–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sauer K, Cullen MC, Rickard AH, Zeef LAH, Davies DG, Gilbert P. 2004. Characterization of nutrient-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 186:7312–7326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrova OE, Sauer K. 2009. A novel signaling network essential for regulating Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000668. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank KL, Reichert EJ, Piper KE, Patel R. 2007. In vitro effects of antimicrobial agents on planktonic and biofilm forms of Staphylococcus lugdunensis clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:888–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Mah T-F. 2008. Involvement of a novel efflux system in biofilm-specific resistance to antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 190:4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauer K, Camper AK. 2001. Characterization of phenotypic changes in Pseudomonas putida in response to surface-associated growth. J. Bacteriol. 183:6579–6589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allegrucci M, Sauer K. 2007. Characterization of colony morphology variants isolated from Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 189:2030–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allegrucci M, Sauer K. 2008. Formation of Streptococcus pneumoniae non-phase-variable colony variants is due to increased mutation frequency present under biofilm growth conditions. J. Bacteriol. 190:6330–6339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Southey-Pillig CJ, Davies DG, Sauer K. 2005. Characterization of temporal protein production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 187:8114–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McBain AJ, Bartolo RG, Catrenich CE, Charbonneau D, Ledder RG, Rickard AH, Symmons SA, Gilbert P. 2003. Microbial characterization of biofilms in domestic drains and the establishment of stable biofilm microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:177–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrova OE, Sauer K. 2010. The novel two-component regulatory system BfiSR regulates biofilm development by controlling the small RNA rsmZ through CafA. J. Bacteriol. 192:5275–5288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McPhee JB, Lewenza S, Hancock REW. 2003. Cationic antimicrobial peptides activate a two-component regulatory system, PmrA-PmrB, that regulates resistance to polymyxin B and cationic antimicrobial peptides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 50:205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulcahy H, Charron-Mazenod L, Lewenza S. 2008. Extracellular DNA chelates cations and induces antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000213. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wurtzel O, Yoder-Himes DR, Han K, Dandekar AA, Edelheit S, Greenberg EP, Sorek R, Lory S. 2012. The single-nucleotide resolution transcriptome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in body temperature. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002945. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macfarlane ELA, Kwasnicka A, Hancock REW. 2000. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PhoP-PhoQ in resistance to antimicrobial cationic peptides and aminoglycosides. Microbiology 146:2543–2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicas TI, Hancock RE. 1980. Outer membrane protein H1 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement in adaptive and mutational resistance to ethylenediaminetetraacetate, polymyxin B, and gentamicin. J. Bacteriol. 143:872–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogle JW, Janda JM, Woods DE, Vasil ML. 1987. Characterization and use of a DNA probe as an epidemiological marker for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 155:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Struelens MJ, Schwam V, Deplano A, Baran D. 1993. Genome macrorestriction analysis of diversity and variability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains infecting cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2320–2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, Saenphimmachak C, Hoffman LR, D'Argenio DA, Miller SI, Ramsey BW, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, Burns JL, Kaul R, Olson MV. 2006. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:8487–8492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolz C, Kiosz G, Ogle JW, Vasil ML, Schaad U, Botzenhart K, Döring G. 1989. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cross-colonization and persistence in patients with cystic fibrosis. Use of a DNA probe. Epidemiol. Infect. 102:205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huse HK, Kwon T, Zlosnik JEA, Speert DP, Marcotte EM, Whiteley M. 2010. Parallel evolution in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over 39,000 generations in vivo. mBio 1(4):e00199-10. 10.1128/mBio.00199-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monsieurs P, De Keersmaecker S, Navarre WW, Bader MW, De Smet F, McClelland M, Fang FC, De Moor B, Vanderleyden J, Marchal K. 2005. Comparison of the PhoPQ regulon in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Evol. 60:462–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soncini FC, Groisman EA. 1996. Two-component regulatory systems can interact to process multiple environmental signals. J. Bacteriol. 178:6796–6801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poole K. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front. Microbiol. 2:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herrmann G, Yang L, Wu H, Song Z, Wang H, Høiby N, Ulrich M, Molin S, Riethmüller J, Döring G. 2010. Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 202:1585–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, Will O, Kaul R, Raymond C, Levy R, Chun-Rong L, Guenthner D, Bovee D, Olson MV, Manoil C. 2003. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14339–14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrova OE, Sauer K. 2012. PAS domain residues and prosthetic group involved in BdlA-dependent dispersion response by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 194:5817–5828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.