Abstract

pIP501 is a conjugative broad-host-range plasmid frequently present in nosocomial Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolates. We focus here on the functional analysis of the type IV secretion gene traG, which was found to be essential for pIP501 conjugative transfer between Gram-positive bacteria. The TraG protein, which localizes to the cell envelope of E. faecalis harboring pIP501, was expressed and purified without its N-terminal transmembrane helix (TraGΔTMH) and shown to possess peptidoglycan-degrading activity. TraGΔTMH was inhibited by specific lytic transglycosylase inhibitors hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose and bulgecin A. Analysis of the TraG sequence suggested the presence of two domains which both could contribute to the observed cell wall-degrading activity: an N-terminal soluble lytic transglycosylase domain (SLT) and a C-terminal cysteine-, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidases (CHAP) domain. The protein domains were expressed separately, and both degraded peptidoglycan. A change of the conserved glutamate residue in the putative catalytic center of the SLT domain (E87) to glycine resulted in almost complete inactivity, which is consistent with this part of TraG being a predicted lytic transglycosylase. Based on our findings, we propose that TraG locally opens the peptidoglycan to facilitate insertion of the Gram-positive bacterial type IV secretion machinery into the cell envelope.

INTRODUCTION

Conjugation machineries of both Gram-negative (G−) and Gram-positive (G+) bacteria are classified as type IV secretion systems (T4SS), which function as translocators and mediate the transport of DNA and/or proteins across the cell envelope (1–3). Nevertheless, it is expected, due to the different architectures of the G− and G+ bacterial cell envelopes, that the mechanism of conjugation in G− and G+ bacterial systems may differ (2, 4–15).

The antibiotic resistance plasmid pIP501 from Streptococcus agalactiae is a model plasmid for conjugation in G+ bacteria and has a very broad host range for conjugative plasmid transfer and mobilization. Its host range includes virtually all tested G+ bacteria, including the multicellular filamentous streptomycetes and Escherichia coli (13, 16). The pIP501 transfer (tra) region encompasses 15 open reading frames (ORFs) that are organized in an operon negatively autoregulated by the first gene product TraA, a biochemically characterized conjugative relaxase (17, 18). The pIP501 tra gene products formerly named Orf1 to Orf15 have been renamed as TraA to TraO, as for the majority of the Tra proteins putative functions have been ascribed. TraEpIP501 is a putative VirB4-like ATPase, TraGpIP501 shows similarities to VirB1-like lytic transglycosylases (LTs), and TraJpIP501 is a putative VirD4-like coupling protein (2, 4, 19). Based on protein-protein interaction studies of the 15 pIP501 Tra proteins by yeast two-hybrid assays and in vitro pulldown assays, a first model of a T4SS-like system of G+ bacterial origin was proposed (4). Furthermore, in vitro ATP binding and hydrolysis were shown for both TraEpIP501 and TraJpIP501 (M. Y. Abajy and E. Grohmann, unpublished data) as well as binding of single-stranded DNA for the putative coupling protein TraJpIP501 (K. Arends and E. Grohmann, unpublished data).

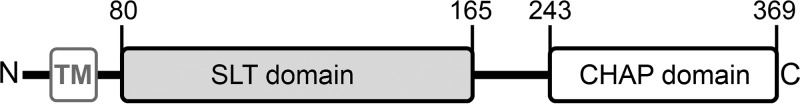

For the VirB1-like enzyme TraG, a modular architecture is anticipated (Fig. 1): at the N terminus of the protein, a putative transmembrane helix (TMH) is predicted which is followed by a soluble lytic transglycosylase (SLT) domain and an N-acetyl-d-glucosamine binding site (20, 21). LTs function as murein lyases by cleaving the β1,4 glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetylglucosamine (22–24). In addition to this, they also form a new glycosidic bond with the C6 hydroxyl group of the same muramic acid residue. Members are found in phages, type II and type III secretion systems, and T4SS (25). At its C terminus, TraG contains a C-terminal cysteine-, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidases (CHAP) domain corresponding to an amidase function. Many proteins with CHAP domains are involved in cell wall metabolism of bacteria; often, the CHAP domain is found in association with other peptidoglycan (PG)-cleaving domains. In these cases, the CHAP domain seems to have an endopeptidase specificity, thus opening the interlinks between several glycan strands (26, 27). The TraG CHAP domain also overlaps with an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (PRK08581) domain (20, 21), indicating the putative cleavage of cross-bridges that interlink murein strands in PG (28).

Fig 1.

Domain composition of TraG. TraG shows a modular structure. The VirB1 ortholog TraGpIP501 protein (GenBank sequence accession no. CAD44387.1) contains 369 amino acids. A transmembrane helix (TMH) is predicted at the N terminus (positions 20 to 36, HMMTOP), as well as a signal peptide with a putative cleavage site at positions 47 to 48 (SignalP 3.0). A specific lytic transglycosylase (SLT) domain is predicted at positions 80 to 165 (gray box); a cysteine-, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidases (CHAP) domain is putatively located at the C terminus (positions 243 to 369, white box). A peptidoglycan binding motif is predicted for the SLT domain (conserved domain search).

The PG layer of the cell wall imposes structural constraints for the assembly of macromolecular secretion systems, such as the T4SS multiprotein complex. The structure of the PG must be rearranged to accommodate such structures, without compromising the integrity of the bacterial cell (29, 30). To overcome this barrier and to facilitate T4SS assembly, one or more PG lyases are generally encoded in the transfer regions of conjugative plasmids (29, 30). The PG lyases involved in locally opening the PG for the assembly of macromolecular secretion systems such as T4SS or type III secretion systems are denominated specialized LTs (25, 31).

For G− bacterial systems, it was shown that VirB1-like proteins encoded by T4S genes are important, but some were found not to be essential for the T4SS to be functional, indicating that their function might be partially complemented by chromosomally encoded LTs (32–35). Transfer frequencies of the R1 plasmid were reduced between 5- and 10-fold in a gene 19 (virB1 homolog) deletion variant (31, 32, 35). virB1 mutants caused attenuated tumor formation in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (33), whereas HP0523 (Cag-gamma), the LT encoded by the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) from Helicobacter pylori, was found to be essential for CagA translocation into human host cells (36). Because of the thick multilayered PG sacculus in G+ bacteria and because of only a limited number of known muramidases encoded on the G+ bacterial chromosome, it was speculated that VirB1-like proteins could have an essential role in DNA/protein transport via T4SS (4). For G+ bacterial systems, Bantwal et al. (30) showed that the peptidoglycan hydrolase TcpG encoded by the tcp transfer locus of plasmid pCW3 is required but not essential for conjugative transfer in Clostridium perfringens. For Lactococcus lactis, a cell wall synthesis inhibitor with a CHAP domain has been shown to be essential for conjugative transfer of the chromosomally located sex factor (37).

Here, we report our results on the functional characterization of traG. TraG exhibits a modular structure. At its N terminus, TraG contains an SLT domain and an N-acetyl-d-glucosamine binding site (20, 21). SLTs catalyze the cleavage of the β1,4-glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, as do “goose-type” lysozymes. However, in addition to this, they also form a new glycosidic bond with the C6 hydroxyl group of the same muramic acid residue. Members are found in phages, type II and type III secretion systems, and T4SS (25). At its C terminus, TraG contains a CHAP domain corresponding to an amidase function. Many proteins with CHAP domains are involved in cell wall metabolism of bacteria; often, the CHAP domain is found in association with other peptidoglycan-cleaving domains. In these cases, the CHAP domain seems to have an endopeptidase specificity, thus opening the interlinks between several glycan strands (26, 27). The TraG CHAP domain also overlaps with an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (PRK08581) domain (20, 21), indicating the putative cleavage of cross-bridges that interlink murein strands in PG (28).

A traG-knockout mutant showed that the protein is indispensable for pIP501 transfer between enterococci. In vivo localization of the TraG protein revealed an association of the protein with the Enterococcus cell envelope. TraG was expressed and purified without its TMH, and TraGΔTMH was demonstrated to possess PG cleavage activity on PG isolated from Enterococcus spp. and E. coli. Furthermore, we could demonstrate inhibition of TraG's activity by bulgecin A and hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose, known inhibitors of LTs, suggesting that the proposed SLT domain was inhibited. There was a residual activity observed with the LT inhibitors which is expected and consistent with the presence of a functionally independent CHAP domain in TraG. In accordance with the proposed two-domain structure of TraG, both domains, when assayed independently, demonstrated PG-degrading activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. If not stated otherwise, all E. faecalis strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Condalab, Madrid, Spain) at 37°C. BHI medium was supplemented, when required, with the following antibiotics: 50 μg fusidic acid (Fus)/ml and 20 μg chloramphenicol (Cm)/ml for E. faecalis JH2-2(pIP501); 1 mg spectinomycin (Spec)/ml, 10 μg tetracycline (Tet)/ml, and 20 μg erythromycin (Em)/ml for E. faecalis CK111(pCF10-101, pKAΔtraG); 50 μg Fus/ml, 20 μg Cm/ml, and 100 μg gentamicin (Gent)/ml for E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501, pKAΔtraG); and 1.5 mg streptomycin (Sm)/ml for E. faecalis OG1X. In the case of E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501, pKAΔtraG), BHI medium was amended with 200 μg X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)/ml. E. coli XL10 (Stratagene) and BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL (Stratagene) harboring derivatives of pMAL-c2x (New England BioLabs), pQTEV (38), or pBlueScript SK− (Stratagene) were grown in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg ampicillin (Ap)/ml and 50 μg Cm/ml at 37°C. E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen) harboring pEU327 or derivatives thereof was grown in LB medium amended with 100 μg Spec/ml, E. coli EC1000(pCJK47) was grown in BHI medium with 500 μg Em/ml, and E. coli EC1000(pKAΔtraG) was grown in BHI medium supplemented with 20 μg Gent/ml.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| XL10 | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac Hte [F′ proAB lac IqZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr) Amy Cmr] | Stratagene |

| BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL | F− ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) dcm+ Tetr gal λ (DE3) endA Hte [argU ileY leuW Cmr] | Stratagene |

| EC1000 | F− RepA+ araD139 (araABC-leu)7679 galU galK lacX74 rspL thi Kmr | 61 |

| BL21 Star-pLysS | F− omp T hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm rne 131 (DE3) pLysS (Camr) | Invitrogen |

| Top10 | F− mcr A Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | F− ϕ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZ YA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| One Shot Mach1-T1R | F− ϕ80(lacZ)ΔM15 Δlac X74 hsdR(rK− mK+) ΔrecA1398 endA1 tonA | Invitrogen |

| E. faecalis | ||

| JH2-2 | Rifr Fusr | 62 |

| OG1RF | Rifr Fusr | 63 |

| CK111 | OG1Sp upp4::P23repA4 Specr | 39 |

| OG1X | Smr | 64 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIP501 | tra+ Cmr MLSr | 65 |

| pMAL-c2x | Ptac lacIq malE lacZ Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pQTEV | Pt4 lacIq His7 Apr | 38 |

| pBlueScript SK− | pUC ori lacZ Apr | Stratagene |

| pCJK47 | oriTpCF10 P-pheS* pORI280 derivative Emr | 39 |

| pCF10-101 | pCF10ΔoriT2 | 39 |

| pKA | pCJK47 aacA-aphD at BglII site; Emr Gentr | This study |

| pKAΔtraG | pKA with traG up- and downstream regions at EcoRI/XbaI sites | This study |

| pIP501ΔtraG | pIP501 traG in-frame deletion | This study |

| pEU327 | E. coli/G+ bacterial shuttle plasmid, Specr xylA promoter | 42 |

| pEU327-traGΔTMH | pEU327 with traGΔTMH | This study |

Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Rifr, rifampin resistance; Fusr, fusidic acid resistance; Specr, spectinomycin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Gentr, gentamicin resistance; MLSr, macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance; tra+, transfer proficient.

Construction of a traG in-frame knockout mutant.

A pIP501 traG in-frame deletion mutant was obtained using an allelic exchange method described by Kristich et al. (39) with minor modifications. First, the pSK41 Gent resistance gene aacA-aphD encompassing both the promoter and terminator sequence (40) was amplified by PCR using primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The PCR product was cut with BglII and cloned into plasmid pCJK47/BglII, thus delivering the Gent resistance-encoding vector pKA.

Second, fragments of the pIP501 traG up- and downstream (1,017-bp and 1,038-bp, respectively) regions were amplified by PCR using primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material and subcloned into plasmid pBlueScript SK− (Stratagene) via EcoRI/BamHI and BamHI/XbaI, respectively. The fused up- and downstream regions were cut with EcoRI/XbaI and inserted into EcoRI/XbaI-cut plasmid pKA, thus delivering pKAΔtraG. Subsequently, the conjugative strain E. faecalis CK111(pCF10-101) (39) was transformed with the suicidal vector pKAΔtraG by electroporation (41). pKAΔtraG was maintained in E. faecalis CK111 by P23repA4 encoded in trans on the chromosome.

To transfer pKAΔtraG from E. faecalis CK111(pCF10-101, pKAΔtraG) to the recipient E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501), a biparental mating was performed. Transconjugants were selected on BHI medium supplemented with 50 μg Fus/ml, 20 μg Cm/ml, 100 μg Gent/ml, and 200 μg X-Gal/ml and screened for the integration of plasmid pKAΔtraG into pIP501 at homologous sites with primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Transconjugants in which pKAΔtraG had integrated up- or downstream of traG were grown on MM9YEG agar supplemented with 10 mM dl-p-chlorophenylalanine (39) (Sigma-Aldrich) and subsequently screened for traG in-frame deletion by PCR. The traG in-frame deletion (pIP501ΔtraG) was verified by PCR with flanking primer pairs binding outside the cloned region (see Table S1) and sequencing of the PCR product.

Western blot analysis of pIP501 T4SS proteins.

E. faecalis OG1RF, OG1RF(pIP501), and OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG) were grown at 37°C in BHI medium overnight. The cultures were centrifuged (4,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the pellet was washed in 5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) and resuspended in 0.75 ml lysis buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 [pH 7.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 μl of 1-mg/ml DNase I). The cells were broken by sonication (30% intensity, 30 s with 0.5-s pulses; Sonopuls HD2070; Bandelin). The lysate was kept on ice for 30 min and centrifuged (4,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C) to remove unlysed cells. Fifteen microliters of the supernatant was mixed with 6 μl of 4× SDS loading buffer. The samples were loaded onto 18% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, separated by electrophoresis, and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) using liquid transfer for 90 min at 90 mA (Mini Protean III system; Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked in RotiBlock blocking solution (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The pIP501 T4SS proteins, TraH, TraK, and TraM, were detected through immunodetection with primary polyclonal anti-TraHΔTMH, anti-TraKΔTMH, and anti-TraMΔTMH antibodies and a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Promega).

Complementation of pIP501ΔtraG.

To complement the markerless traG deletion in trans, the expression vector pEU327 (42) was selected. traG was amplified from pIP501 with TraG_SalI-fw and TraG_SalI-rev primers. To amplify traG with its own ribosomal binding site (RBS), TraG_RBS_SalI-fw and TraG_Sal1-rev primers were used (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The 1,109- and 1,132-bp PCR products were cut with SalI and inserted into pEU327/SalI. The ligation mixtures were transformed into E. coli DH5α, Top10 (Life Technologies), XL10 Gold (Promega), and BL21 Star-pLysS (Life Technologies), respectively, and incubated at 37°C. With all the E. coli strains tested, only a few tiny colonies were obtained on selective agar plates (100 μg Spec/ml for pEU327 and 34 μg Cm/ml for E. coli BL21 Star-pLysS). No growth of putative transformants was obtained after inoculation into fresh selective solid or liquid medium, respectively, not even after incubation for up to 7 days. The cloning experiment with the traG wild-type gene cloned into pEU327 was repeated applying E. coli DH5α and One Shot Mach1-T1R chemically competent E. coli cells (Invitrogen) as host and testing distinct incubation temperatures for the selective plates, namely, room temperature, 30°C, and 37°C. Transformants were tested for the insertion of traG. None of them contained traG. Cloning of traG into the expression vector pMSP3535VA (43) also failed. Finally, traG without the putative TMH was amplified from pIP501 with TraG_Δtmh_SalI-fw and TraG_SalI-rev primers. The 1,013-bp PCR product was cut with SalI and inserted into pEU327/SalI. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5α cells. Transformants obtained after 2 days of growth at 30°C were tested for the insertion of the traGΔTMH fragment by sequencing with pEU327_Test_SalI_fw and pEU327_Test_SalI_rev primers (see Table S1). Plasmid DNA of pEU327-traGΔTMH was electroporated into E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG).

Filter matings.

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 in fresh BHI medium and incubated until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 was reached. A 1:10 mixture of donor E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501) and E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG), respectively, and recipient (E. faecalis OG1X) cells were collected on a sterile nitrocellulose membrane filter (0.45 μm; Millipore). The membrane was incubated overnight cell-side-up on BHI agar at 37°C. Serial dilutions of the cells recovered by suspension in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were plated on BHI agar supplemented with 1 mg Sm/ml to enumerate recipients and 1 mg Sm/ml and 20 μg Cm/ml to enumerate transconjugants, respectively. To analyze complementation of the pIP501ΔtraG in-frame deletion in trans, matings were performed with E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG), E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG, pEU327-traGΔTMH), E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG, pEU327), and E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501) as donor, respectively, and E. faecalis OG1X as recipient. Transconjugants were selected on BHI agar supplemented with 1.5 mg Sm/ml, 20 μg Em/ml, and 20 μg Cm/ml. Recipients were selected on BHI agar amended with 1.5 mg Sm/ml. The matings were repeated three times.

Expression and purification of TraGΔTMH, SLTTraG, SLT(E87G)TraG, and CHAPTraG for biochemical studies.

All proteins were expressed as maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins and purified as described in the supplemental material (see Fig. S1). Prior to application in the muramidase assay, they were concentrated to 0.7 mg/ml (TraGΔTMH) and to 5 mg/ml for the protein domains.

l-[3H]lysine labeling of PG from E. faecalis.

Five milliliters of an E. faecalis JH2-2 overnight (o/n) culture was transferred to 100 ml Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) (supplemented with 25 μg rifampin [Rif]/ml). One milliliter l-[3H]lysine (1 mCi) was added, and the culture was grown at 37°C and 225 rpm to an OD540 of 0.5. Cells were harvested (7,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and washed with 8 ml 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 4°C. The pellet was vacuum dried and suspended in 8 ml 4% SDS. The following steps were performed as described under “PG isolation and purification” in the supplemental material. The labeled PG was lyophilized and stored at −80°C.

2,6-[3H]diaminopimelic acid labeling of PG from E. coli.

Five milliliters of an E. coli DH5α o/n culture was transferred to 100 ml M9 minimal broth, and 1 ml 2,6-[3H]diaminopimelic acid (1 mCi) was added. Incubation at 37°C continued until stationary phase was reached (OD600 of ca. 1.0). The protocol continued as described under “PG isolation and purification from E. coli DH5α” in the supplemental material.

Muramidase assay.

The muramidase assay is based on the measurement of the solubilization of l-[3H]lysine-labeled PG from E. faecalis and 2,6-[3H]diaminopimelic acid-labeled PG from E. coli (31). Labeled PG (approximately 5,000 cpm) was incubated with 3 μM respective protein in a total volume of 100 μl 20 mM Bis-Tris buffer (pH 5.3) for 30 min at 37°C. One percent cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) was added to precipitate the insoluble substrate. Samples were kept on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation (4 min at 17,000 × g and 4°C), 160 μl of the supernatant was added to 7 ml scintillation cocktail (Ionophor Gold scintillation cocktail; Fuji, Tokyo, Japan). Radioactivity was measured using the Wallac 1409 liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). Purified MBP and lysozyme from hen egg white were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Cy3 labeling of PG.

Cy3 labeling of PG was performed according to the method of Zahrl et al. (31) with modifications. Five hundred microliters PG from E. faecalis JH2-2 (1 mg PG in 500 μl distilled water) was incubated with 50 μl 1 M borate buffer (pH 9.6) and 5 μl Cy3 N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester (1 mg/ml in dimethyl formamide) for 60 min at room temperature. Excess Cy3 was removed by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 5 min at 4°C). Cy3-labeled PG was stored at −20°C.

Cy3 spot assay.

The Cy3 spot assay was performed according to the method of Zahrl et al. (31) with modifications. Eight-well glass slides were coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed with deionized water, and dried. Ten microliters deionized water and 1 μl Cy3-labeled PG (containing approximately 2 μg PG) were spotted onto the poly-l-lysine-coated wells and incubated at room temperature for 45 min in the dark. The slides were rinsed with deionized water for 2 min, dried at room temperature in the dark, and scanned with a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner with 532-nm excitation (GenePix Pro 4.1 software). Ten microliters Bis-Tris buffer (pH 5.3) was loaded onto the PG, and approximately 6 pmol of the respective protein, lysozyme, TraGΔTMH, and MBP, was added. The slides were incubated at 37°C for 2 h 30 min. To remove the digested material, the slides were rinsed with deionized water for 2 min and dried at room temperature. To quantitate the fluorescence signals, dry slides were scanned before and after incubation with the enzyme using an array scanner (Axon GenePix 4000B; photomultiplier tube [PMT] setting, 320; scan power, 33%), and images were obtained and analyzed using the GenePix Pro 4.1 program. Line scans from the images were produced using a 50-pixel (2-mm) window across the center of the PG spots. Relative PG-degrading activity of TraGΔTMH was calculated using the following formula: 100 − [(Fi532b/Fi532a) × 100], where Fi532a is the mean fluorescence intensity of Cy3-labeled PG, corresponding to a total of 460 pixels in a circle with a diameter of 1 mm, before incubation and Fi532b is the same value after incubation, respectively.

To test inhibitory effects of the specific lytic transglycosylase blockers bulgecin A (Hoffman-La Roche) and hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose (Seikagaku, Japan) on the PG hydrolysis activity of TraGΔTMH, the Cy3 spot assay was repeated with the exception that prior to addition of the respective protein the lytic transglycosylase blockers were added in concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 4 mM for hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose and 1 to 20 mM for bulgecin A. Data analysis and calculation of relative PG-degrading activities were done as described above.

Subcellular fractionation of E. faecalis JH2-2(pIP501) and immunolocalization of TraG.

Subcellular fractionation of E. faecalis JH2-2(pIP501) was performed according to the method of Buttaro et al. (44) with modifications. Briefly, E. faecalis JH2-2(pIP501) was grown at 37°C in BHI medium to an OD600 of 0.5. The culture was chilled on ice for 15 min, washed twice in an equal volume of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0), and resuspended (1:50 [vol/vol]) in lysis buffer (50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 [pH 7.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μg/ml DNase, 100 μg/ml RNase). The cells were broken by FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedicals) using lysing matrix E (1.4-mm ceramic spheres, 0.1-mm silica spheres, and 4-mm glass beads; MP Biomedicals). The lysate was centrifuged (1,500 × g, 20 min, 4°C) to remove unlysed cells. The supernatant was transferred and centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to collect the cell wall fraction. Membranes were harvested by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant at 163,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C (50 Ti rotor; OTD Combi ultracentrifuge; Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH) and resuspended in 50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 1% Triton X-100. The remaining supernatant contained the cytoplasmic fraction of proteins.

Subsequently, equal amounts of the cell wall, membrane, and cytoplasmic fraction were applied onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels, separated by electrophoresis, and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) using liquid transfer for 90 min at 90 mA (Mini Protean III system; Bio-Rad). The membrane containing the transferred proteins was initially blocked in RotiBlock blocking solution (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). TraG was then localized in the fractions (cell wall, membrane, and cytoplasm) by immunostaining of TraG with primary polyclonal anti-TraGΔTMH antibodies and a secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Promega).

RESULTS

TraG is an essential T4SS protein.

The indispensability of VirB1 and homologous proteins could not be demonstrated for T4SS originating from G− bacteria (31–35). However, due to the multilayered and cross-linked PG meshwork in G+ bacteria, we raised the question whether a specific PG degradation caused by the putative lytic transglycosylase TraG might be a crucial step during conjugative pIP501 DNA transfer in G+ bacteria. To investigate the potential indispensability of TraG in conjugative transfer, we constructed a pIP501ΔtraG in-frame deletion mutant using the PheS counterselection markerless exchange system (39). Ninety-seven percent of the TraG coding region was thereby deleted, except for the first 5 N-terminal codons and the last 6 C-terminal codons, to not alter transcription and translation of downstream tra genes.

We assessed the influence of the traG deletion on conjugative transfer of pIP501 by biparental matings. Assuming the indispensability of TraG, no transfer should occur in the traG-knockout mutant in a biparental mating in G+ bacteria, whereas transfer rates with an isogenic, traG-proficient pIP501 plasmid should be in the expected range of approximately 10−5 transconjugants per recipient. The biparental matings were performed with donor strains E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG) and isogenic E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501), respectively, and E. faecalis OG1X as recipient.

The isogenic E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501) originated from the same E. faecalis OG1RF strain that harbored the merodiploid pIP501-pKAΔtraG complex. Both the traG-knockout plasmid pIP501ΔtraG and pIP501 used for the biparental mating assay were obtained after excision and segregation of the suicide vector pKAΔtraG from the pIP501-pKAΔtraG complex.

Transfer rates of the traG deletion mutant were below the detection limit of the assay (<3.5 × 10−9 ± 2.4 × 10−9, mean value of three independent assays), whereas transfer rates with the isogenic strain E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501) were at least 20,000 times higher and in the expected range for pIP501 of 7.6 × 10−5 ± 5.7 × 10−5 transconjugants per recipient cell (mean value of three independent assays). As transfer frequencies were in the expected range for pIP501, we can exclude polar effects due to unwarranted suicide vector integration into pIP501. Unfortunately, we were not able to complement the traG knockout in E. faecalis pIP501ΔtraG by supplying the traG wild-type (wt) gene on an expression plasmid in trans. Despite several attempts, it was not possible to clone traG in E. coli/G+ bacterial shuttle vectors. A possible explanation is that TraG is toxic in E. coli even if basal expression is very low. In the natural plasmid context, expression of all pIP501 tra genes is tightly controlled by the first gene product of the tra operon, TraA (18). Furthermore, we tried to complement the traG deletion by supplying traGΔTMH in trans. We obtained transformants of pEU327-traGΔTMH in E. coli, and the plasmid DNA was subsequently electroporated into E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG). However, transfer activity of pIP501 could not be restored by supplying traGΔTMH in trans.

A complete transfer deficiency was observed for the traG-knockout strain (E. faecalis pIP501ΔtraG) and the complementation strain (E. faecalis pIP501ΔtraG, pEU-327-traGΔTMH), as well as for the negative control (E. faecalis pIP501ΔtraG, pEU-327), in three independently performed assays. Transfer frequencies of pIP501 were in the expected range of approximately 5 × 10−5 transconjugants/recipient under the same conditions.

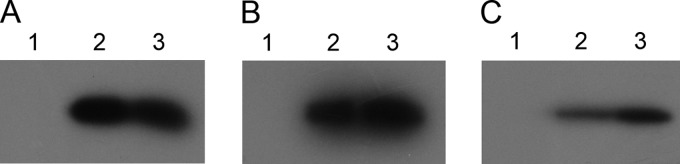

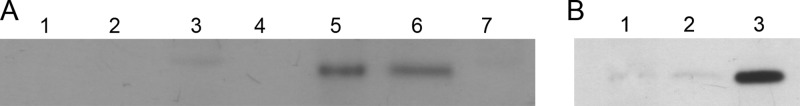

To ensure that the excision of traG by allelic exchange did not alter transcription and translation of downstream tra genes in pIP501ΔtraG that could have caused the failure of complementation, we performed immunoblot assays with protein lysates obtained from E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501) and E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG). Three genes located downstream of traG in the pIP501 tra operon were selected for immunodetection with the respective polyclonal anti-Tra antibodies, namely, traH, traK, and traM. The expression level of all three genes was unaltered in the traG-knockout mutant (Fig. 2), proving that deletion of 97% of the traG coding region exerts no negative effect on expression of the downstream genes in the pIP501 tra operon.

Fig 2.

Expression of traG downstream genes in the pIP501 tra operon is not affected by traG deletion. Immunodetection of proteins TraH (A), TraK (B), and TraM (C) using polyclonal antibodies against the respective proteins showed comparable expression levels for all three proteins in lysates from E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501 wt) and E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG). The plasmid-free E. faecalis OG1RF strain was used as a negative control. Lanes 1, E. faecalis OG1RF lysate; lanes 2, E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501 wt) lysate; lanes 3, E. faecalis OG1RF(pIP501ΔtraG) lysate.

Therefore, the inability of TraGΔTMH to complement the traG knockout could most probably be caused by an incorrect folding of TraGΔTMH due to the missing putative TMH or by a misled location of TraGΔTMH within the enterococcal cell or both.

TraG localizes to the E. faecalis cell envelope.

T4SS of G− bacteria are multiprotein complexes that span the cell envelope (6, 7). It is likely that, due to its indispensability for conjugative pIP501 transfer and its predicted PG-degrading activity, TraG localizes within the cell envelope. In silico predictions postulated TraG being predominantly localized in the cell wall fraction (PSORTb v.3.0.2 [45]) with a TMH (amino acid [aa] positions 17 to 36, CAD44387, HMMTOP [46]) and a possible signal peptide (putative cleavage site between aa 47 and 48, CAD44387, SignalP3.0 [47]). To localize TraG in vivo, an exponentially growing culture of E. faecalis JH2-2(pIP501) was fractionated into cell wall, membrane, and cytoplasmic fractions according to the method of Buttaro et al. (44) with modifications. As expected, TraG was exclusively found in the cell envelope fractions (cell wall and membrane, Fig. 3A). Other results from our lab confirmed that the cell wall fractions were not contaminated with cytoplasmic proteins, since the pIP501 Tra protein TraN, under the same conditions, was exclusively found in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 3B). This is in agreement with the in silico prediction for the cytoplasmic localization of TraN in G+ bacteria (N. Goessweiner-Mohr, K. Arends, E. Grohmann, and W. Keller, unpublished data).

Fig 3.

(A) TraG subcellular localization. TraG localizes to the cell envelope of E. faecalis JH2-2 harboring pIP501. The localization of TraG in the cell fractions was detected by immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-TraG antibodies. Plasmid-free E. faecalis JH2-2 was applied as a negative control. Lane 1, cell wall fraction; lane 2, membrane fraction; lane 3, cytoplasmic fraction; lane 4, empty well; lane 5, cell wall fraction; lane 6, membrane fraction; lane 7, cytoplasmic fraction; lanes 1 to 3 represent samples from E. faecalis JH2-2 cells without pIP501; lanes 5 to 7 contain samples from pIP501-harboring cells. (B) TraN subcellular localization. TraN localizes to the cytoplasmic fraction and thus serves as a negative control for the localization of TraG to the cell envelope. Lane 1, cell wall fraction; lane 2, membrane fraction; lane 3, cytoplasmic fraction.

TraGΔTMH degrades peptidoglycan and is inhibited by hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose and bulgecin A.

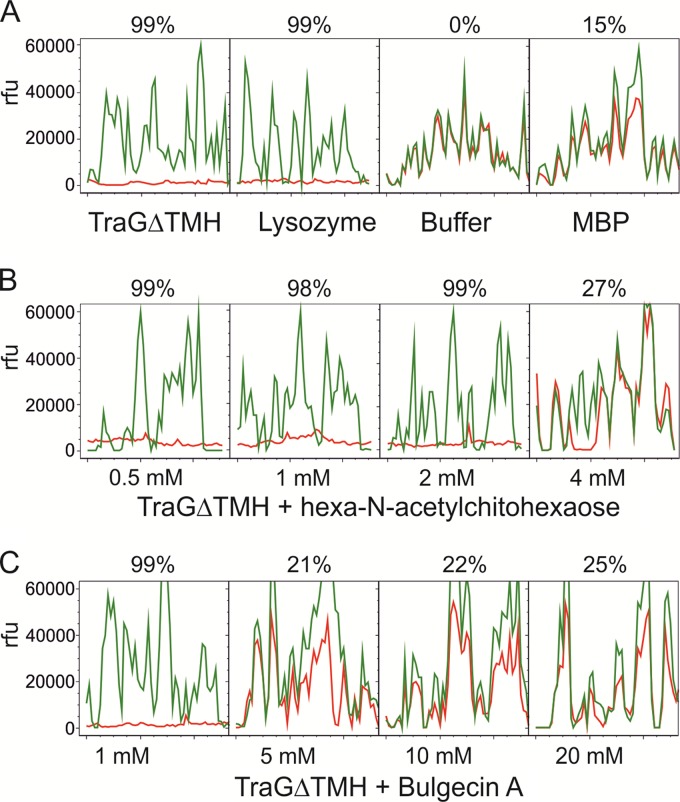

To demonstrate the sequence-inferred PG-degrading activity of TraG in vitro, we performed an assay as described by Zahrl et al. (31) using Cy3-labeled PG from E. faecalis JH2-2. PG-hydrolyzing activity was calculated by comparing fluorescence levels of Cy3 PG spots on a glass surface before and after enzyme treatment (for details, see Materials and Methods). To visualize PG degradation, line scans through the PG spots before and after treatment were superimposed (Fig. 4). PG degradation was observed in the case of TraGΔTMH and lysozyme (99%), whereas for purified MBP, which was used as a negative control in all of the performed assays, no or only minimal background activity (as in this case, 15%) was seen (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Cy3 PG degradation by TraGΔTMH. Cy3-labeled PG was measured before (green lines) and after (red lines) digestion. Line scans are shown for a window of 50 pixels (2 mm). rfu, relative fluorescence units. Values above each box indicate the reduction of the fluorescence in each Cy3 PG spot and therefore reflect enzymatic activity (for details, see Materials and Methods). (A) Cy3 PG was digested with the indicated proteins or incubated with buffer alone. (B and C) Inhibition of TraGΔTMH with indicated concentrations of hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose and bulgecin A, respectively.

To investigate a possible lytic transglycosylase activity of TraGΔTMH, we repeated the Cy3 spot assay in the presence of the specific lytic transglycosylase blockers hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose and bulgecin A, respectively. For hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose, which binds to the active center of LTs but is not a substrate for these enzymes (48–50), concentrations from 0.5 mM to 4 mM were tested: the addition of 4 mM inhibitor reduced TraGΔTMH activity, resulting in a residual activity of 27% (Fig. 4B). For bulgecin A, concentrations between 1 mM and 20 mM were added (Fig. 4C). Concentrations of 5 to 20 mM bulgecin A resulted in 21 to 25% residual TraGΔTMH activity (no PG degradation occurred with the MBP control in this experiment; data not shown). Since bulgecin A, a specific glycopeptide inhibitor of LTs (51), is known to bind to the active site of LTs and is frequently used as a ligand in crystallographic studies revealing the structure and function of LTs (52, 53), our data suggest binding (at 5 mM bulgecin A) of the inhibitor to the predicted SLT domain, leaving the CHAP domain uninhibited. To accurately quantify PG degradation activity of TraGΔTMH and its domains, a radioactive muramidase assay was performed.

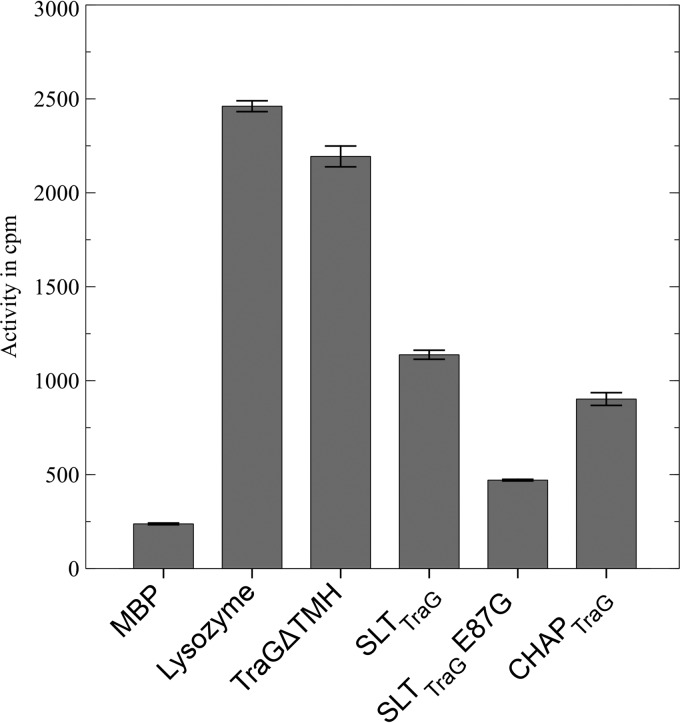

TraG SLT and CHAP domains degrade PG independently of each other.

To further analyze whether the residual TraGΔTMH activity correlates with a putative PG-degrading activity of the CHAP domain, we expressed and purified both domains independently. PG hydrolase activity of TraGΔTMH and its N-terminal SLT and C-terminal CHAP domain was investigated by a radioactive muramidase assay in which solubilized cell wall components were measured with two different substrates (PG from G+ and G− bacteria, respectively). TraGΔTMH showed high muramidase activity (1,955.6 cpm after subtracting background activity of 215.5 cpm) when using l-[3H]lysine-labeled PG from E. faecalis JH2-2 and was comparable to the activity of lysozyme from hen egg white (2,438 cpm) under the same conditions. SLTTraG still exhibited 46% (900.07 cpm) of TraGΔTMH enzyme activity (1,955.6 cpm), and CHAPTraG exhibited 34% of TraGΔTMH activity. A single-amino-acid change in the putative catalytic center of TraGSLT (E87G) resulted in a 74% reduction of muramidase activity as measured for the SLT(E87G)TraG domain in comparison to SLTTraG (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

TraGΔTMH and mutant protein muramidase activity on l-[3H]lysine-labeled PG from E. faecalis JH2-2. Activities (in cpm) are given as average values of three independent measurements with standard deviations. MBP and lysozyme (from hen egg white) were applied as negative and positive controls, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we demonstrated the essential function of the VirB1-like PG hydrolase TraG in conjugative plasmid transfer of broad-host-range plasmid pIP501. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that indispensability of a VirB1-like PG hydrolase could be shown for T4SS-mediated DNA/protein transport. Bantwal and coworkers constructed deletion mutants of the pCW3 virB1 homolog, tcpG. The pCW3ΔtcpG mutants showed ca.-1,000-fold-reduced conjugative plasmid transfer capacity (30) whereas the pIP501ΔtraG variant did not show any residual transfer activity in intraspecies transfer between different E. faecalis strains. Bantwal et al. (30) explained the residual pCW3 transfer activity by putative functional redundancy between PG hydrolases produced by C. perfringens, with chromosomally encoded enzymes able to catalyze the PG degradation required for conjugative transfer, albeit at lower efficiency. For E. faecalis, only scarce information on genomic PG hydrolases is available; most literature deals with the two autolysins, AtlA and Atn, and their role in autolysis of E. faecalis cells as well as in DNA-dependent Enterococcus biofilm development (54–56). No putative role in controlled local opening of the PG has been proposed for these enzymes.

Both TraG domains, the SLTTraG and the CHAPTraG domains, have been expressed separately and shown to possess PG degradation activity on PG from E. faecalis (Fig. 5). PG degradation activity of the SLTTraG domain is in agreement with lytic transglycosylase activity of several putative lytic transglycosylases encoded by G− bacterial T4SS, P19 from the conjugative resistance plasmid R1, VirB1 encoded by the Ti plasmid of A. tumefaciens, VirB1 from the small chromosome of Brucella suis, and HP0523 encoded by the cag pathogenicity island of H. pylori (31); AtlA from the Neisseria gonorrhoeae T4SS-secreting DNA (57); and TcpG encoded by the G+ bacterial T4SS from C. perfringens plasmid pCW3 (30).

We mutated the putative catalytic residue of SLTTraG, the glutamate at position 87 (GenBank sequence accession no. CAD44387.1), by replacement with glycine, generating SLT(E87G)TraG and introducing a BamHI restriction site to facilitate screening for mutants. Surprisingly, the mutant protein retained about 26% of its LT activity compared to SLTTraG. Supposedly, the mutated catalytic active glutamate at position 87 (GenBank CAD44387.1) in TraG could be partially complemented by a second putative ES motif at positions 100 to 101 (GenBank CAD44387.1) (positions 48 to 49, HMM logo, http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/family/PF13702.1#tabview=tab4 [58]), thus explaining the strongly reduced, but not completely abolished, activity of SLT(E87G)TraG.

TraGΔTMH PG-degrading activity was significantly reduced by the specific lytic transglycosylase inhibitors bulgecin A and hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose (48, 49, 51), suggesting a possible lytic transglycosylase activity for TraG. For IpgF, the lytic transglycosylase from the plasmid-encoded type III secretion system of Shigella sonnei (59, 60), a similar observation was made with hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose. It completely inhibited IpgF at a concentration of 4 mM. Zahrl et al. (31) showed that, in contrast, lysozyme was not affected by the presence of hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose, which is in accordance with the observation that this substance is not a substrate for lysozyme and solely inhibits lytic transglycosylases (48, 49). Zahrl et al. (31) also tested bulgecin A, which has also been described as an inhibitor of lytic transglycosylases (51), and found that a concentration of 20 mM was sufficient to completely inhibit IpgF. TraGΔTMH, however, was not totally inhibited by bulgecin A. Its activity was reduced to around 21 to 25% residual activity at 5 mM and higher (up to 20 mM) bulgecin A concentrations, which could be due to binding of bulgecin A to the SLT domain but not to the CHAP domain. This observation is consistent with the SLT and CHAP domains of TraG representing independent domains, with both displaying PG-degrading activity.

TraGΔTMH was also able to degrade 2,6-[3H]diaminopimelic acid-labeled PG from E. coli DH5α, albeit with less activity. For TraGΔTMH, 2,398 cpm of soluble PG fragments was measured; for lysozyme, we obtained 6,712 cpm, thus resulting in 38% activity for TraGΔTMH compared to lysozyme. These data are in agreement with the broad host range of pIP501, which was, in addition to self-transfer to virtually all Gram-positive bacteria, shown to transfer in and be stably maintained in E. coli (16). The reduced TraGΔTMH PG degradation activity observed for E. coli PG might be compensated for by other LTs encoded on the E. coli chromosome.

Our data strongly suggest that TraG is a PG-degrading protein that is indispensable for the intraspecies conjugative transfer of pIP501 in E. faecalis. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that indispensability of a VirB1-homologous protein has been shown for conjugative plasmid transfer.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gary Dunny for the gift of strains E. coli EC1000 and E. faecalis CK111 and plasmids pCF10-101 and pCJK47. The skillful technical assistance of Christine Bohn is highly acknowledged. Support during data collection at beamline X33 at DESY by the EMBL staff is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by grants MISSEX and Concordia microbial dynamics from BMWi/DLR to E.G. and by a grant from the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF project P19794-B12) to W.K. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under BioStruct-X (grant agreement no. 283570).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02263-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Francia MV, Fujimoto S, Tille P, Weaver KE, Clewell DB. 2004. Replication of Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responding plasmid pAD1: location of the minimal replicon and oriV site and RepA involvement in initiation of replication. J. Bacteriol. 186:5003–5016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Martinez CE, Christie PJ. 2009. Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:775–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, de la Cruz F. 2009. The diversity of conjugative relaxases and its application in plasmid classification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:657–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abajy MY, Kopec J, Schiwon K, Burzynski M, Doring M, Bohn C, Grohmann E. 2007. A type IV-secretion-like system is required for conjugative DNA transport of broad-host-range plasmid pIP501 in Gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:2487–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter CJ, Bantwal R, Bannam TL, Rosado CJ, Pearce MC, Adams V, Lyras D, Whisstock JC, Rood JI. 2012. The conjugation protein TcpC from Clostridium perfringens is structurally related to the type IV secretion system protein VirB8 from Gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 83:275–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandran V, Fronzes R, Duquerroy S, Cronin N, Navaza J, Waksman G. 2009. Structure of the outer membrane complex of a type IV secretion system. Nature 462:1011–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fronzes R, Schafer E, Wang L, Saibil HR, Orlova EV, Waksman G. 2009. Structure of a type IV secretion system core complex. Science 323:266–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes CS, Aoki SK, Low DA. 2010. Bacterial contact-dependent delivery systems. Annu. Rev. Genet. 44:71–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Cruz F, Frost LS, Meyer RJ, Zechner EL. 2010. Conjugative DNA metabolism in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:18–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rêgo AT, Chandran V, Waksman G. 2010. Two-step and one-step secretion mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria: contrasting the type IV secretion system and the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Biochem. J. 425:475–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smillie C, Garcillan-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EPC, de la Cruz F. 2010. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:434–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallden K, Rivera-Calzada A, Waksman G. 2010. Microreview: type IV secretion systems: versatility and diversity in function. Cell. Microbiol. 12:1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grohmann E, Muth G, Espinosa M. 2003. Conjugative plasmid transfer in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:277–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grohmann E. 2006. Mating cell-cell channels in conjugating bacteria, p 21–38 In Baluska F, Volkmann D, Barlow PW. (ed), Cell-cell channels. Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, TX [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Staddon JH, Dunny GM. 2007. Specificity determinants of conjugative DNA processing in the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10 and the Lactococcus lactis plasmid pRS01. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1549–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurenbach B, Bohn C, Prabhu J, Abudukerim M, Szewzyk U, Grohmann E. 2003. Intergeneric transfer of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pIP501 to Escherichia coli and Streptomyces lividans and sequence analysis of its tra region. Plasmid 50:86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopec J, Bergmann A, Fritz G, Grohmann E, Keller W. 2005. TraA and its N-terminal relaxase domain of the Gram-positive plasmid pIP501 show specific oriT binding and behave as dimers in solution. Biochem. J. 387:401–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurenbach B, Kopéc J, Mägdefrau M, Andreas K, Keller W, Bohn C, Abajy MY, Grohmann E. 2006. The TraA relaxase autoregulates the putative type IV secretion-like system encoded by the broad-host-range Streptococcus agalactiae plasmid pIP501. Microbiology 152:637–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arends K, Schiwon K, Sakinc T, Hubner J, Grohmann E. 2012. Green fluorescent protein-labeled monitoring tool to quantify conjugative plasmid transfer between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:895–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Tasneem A, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zhang N, Bryant SH. 2009. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D205. 10.1093/nar/gkn845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Omelchenko MV, Robertson CL, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zhang N, Zheng C, Bryant SH. 2011. CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D225. 10.1093/nar/gkq1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Höltje J, Mirelman D, Sharon N, Schwarz U. 1975. Novel type of murein transglycosylase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 124:1067–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mett H, Keck W, Funk A, Schwarz U. 1980. Two different species of murein transglycosylase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 144:45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel H, Kazemier B, Keck W. 1991. Murein-metabolizing enzymes from Escherichia coli: sequence analysis and controlled overexpression of the slt gene, which encodes the soluble lytic transglycosylase. J. Bacteriol. 173:6773–6782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koraimann G. 2003. Lytic transglycosylases in macromolecular transport systems of Gram-negative bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:2371–2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bateman A, Rawlings ND. 2003. The CHAP domain: a large family of amidases including GSP amidase and peptidoglycan hydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:234–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Layec S, Decaris B, Leblond-Bourget N. 2008. Characterization of proteins belonging to the CHAP-related superfamily within the Firmicutes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajimura J, Fujiwara T, Yamada S, Suzawa Y, Nishida T, Oyamada Y, Hayashi I, Yamagishi J, Komatsuzawa H, Sugai M. 2005. Identification and molecular characterization of an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase Sle1 involved in cell separation of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1087–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dijkstra AJ, Keck W. 1996. Identification of new members of the lytic transglycosylase family in Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bantwal R, Bannam TL, Porter CJ, Quinsey NS, Lyras D, Adams V, Rood JI. 2012. The peptidoglycan hydrolase TcpG is required for efficient conjugative transfer of pCW3 in Clostridium perfringens. Plasmid 67:139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahrl D, Wagner M, Bischof K, Bayer M, Zavecz B, Beranek A, Ruckenstuhl C, Zarfel G, Koraimann G. 2005. Peptidoglycan degradation by specialized lytic transglycosylases associated with type III and type IV secretion systems. Microbiology 151:3455–3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayer M, Eferl R, Zellnig G, Teferle K, Dijkstra A, Koraimann G, Högenauer G. 1995. Gene 19 of plasmid R1 is required for both efficient conjugative DNA transfer and bacteriophage R17 infection. J. Bacteriol. 177:4279–4288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mushegian AR, Fullner KJ, Koonin EV, Nester EW. 1996. A family of lysozyme-like virulence factors in bacterial pathogens of plants and animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:7321–7326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohne J, Yim A, Binns AN. 1998. The Ti plasmid increases the efficiency of Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a recipient in virB-mediated conjugal transfer of an IncQ plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:7057–7062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayer M, Iberer R, Bischof K, Rassi E, Stabentheiner E, Zellnig G, Koraimann G. 2001. Functional and mutational analysis of p19, a DNA transfer protein with muramidase activity. J. Bacteriol. 183:3176–3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer W, Püls J, Buhrdorf R, Gebert B, Odenbreit S, Haas R. 2001. Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for CagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stentz R, Wegmann U, Parker M, Bongaerts R, Lesaint L, Gasson M, Shearman C. 2009. CsiA is a bacterial cell wall synthesis inhibitor contributing to DNA translocation through the cell envelope. Mol. Microbiol. 72:779–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheich C, Niesen FH, Seckler R, Bussow K. 2004. An automated in vitro protein folding screen applied to a human dynactin subunit. Protein Sci. 13:370–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2007. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 57:131–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rouch DA, Byrne ME, Kong YC, Skurray RA. 1987. The aacA-aphD gentamicin and kanamycin resistance determinant of Tn4001 from Staphylococcus aureus: expression and nucleotide sequence analysis. Microbiology 133:3039–3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bae T, Kozlowicz B, Dunny GM. 2002. Two targets in pCF10 DNA for PrgX binding: their role in production of Qa and prgX mRNA and in regulation of pheromone-inducible conjugation. J. Mol. Biol. 315:995–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eichenbaum Z, Federle M, Marra D, de Vos W, Kuipers O, Kleerebezem M, Scott J. 1998. Use of the lactococcal nisA promoter to regulate gene expression in gram-positive bacteria: comparison of induction level and promoter strength. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2763–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buttaro BA, Antiporta MH, Dunny GM. 2000. Cell-associated pheromone peptide (cCF10) production and pheromone inhibition in E. faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4926–4933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, Dao P, Sahinalp SC, Ester M, Foster LJ, Brinkman FSL. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tusnady GE, Simon I. 2001. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17:849–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340:783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song H, Inaka K, Maenaka K, Matsushima M. 1994. Structural changes of active site cleft and different saccharide binding modes in human lysozyme co-crystallized with hexa-N-acetyl-chitohexaose at pH 4.0. J. Mol. Biol. 244:522–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung AK, Duewel HS, Honek JF, Berghuis AM. 2001. Crystal structure of the lytic transglycosylase from bacteriophage lambda in complex with hexa-N-acetylchitohexaose. Biochemistry 40:5665–5673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Straaten KE, Barends TRM, Dijkstra BW, Thunnissen AM. 2007. Structure of Escherichia coli lytic transglycosylase MltA with bound chitohexaose: implications for peptidoglycan binding and cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 282:21197–21205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Templin MF, Edwards DH, Höltje J. 1992. A murein hydrolase is the specific target of bulgecin in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:20039–20043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:259–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fibriansah G, Gliubich FI, Thunnissen AM. 2012. On the mechanism of peptidoglycan binding and cleavage by the endo-specific lytic transglycosylase MltE from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 51:9164–9177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guiton PS, Hung CS, Kline KA, Roth R, Kau AL, Hayes E, Heuser J, Dodson KW, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. 2009. Contribution of autolysin and sortase A during Enterococcus faecalis DNA-dependent biofilm development. Infect. Immun. 77:3626–3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas VC, Hiromasa Y, Harms N, Thurlow L, Tomich J, Hancock LE. 2009. A fratricidal mechanism is responsible for eDNA release and contributes to biofilm development of Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1022–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubee V, Chau F, Arthur M, Garry L, Benadda S, Mesnage S, Lefort A, Fantin B. 2011. The in vitro contribution of autolysins to bacterial killing elicited by amoxicillin increases with inoculum size in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:910–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kohler PL, Hamilton HL, Cloud-Hansen K, Dillard JP. 2007. AtlA functions as a peptidoglycan lytic transglycosylase in the Neisseria gonorrhoeae type IV secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 189:5421–5428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schuster-Böckler B, Schultz J, Rahmann S. 2004. HMM Logos for visualization of protein families. BMC Bioinformatics 5:7. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allaoui A, Ménard R, Sansonetti P, Parsot C. 1993. Characterization of the Shigella flexneri ipgD and ipgF genes, which are located in the proximal part of the mxi locus. Infect. Immun. 61:1707–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Rusniok C, Nedjari H, d'Hauteville H, Kunst F, Sansonetti P, Parsot C. 2000. The virulence plasmid pWR100 and the repertoire of proteins secreted by the type III secretion apparatus of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 38:760–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leenhouts K, Buist G, Bolhuis A, Kiel J, Mierau I, Dabrowska M, Venema G, Kok J. 1996. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacob A, Hobbs S. 1974. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J. Bacteriol. 117:360–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dunny GM, Brown B, Clewell DB. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:3479–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ike Y, Craig RA, White BA, Yagi Y, Clewell D. 1983. Modification of Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromones after acquisition of plasmid DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:5369–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evans R, JR, Macrina F. 1983. Streptococcal R plasmid pIP501: endonuclease site map, resistance determinant location, and construction of novel derivatives. J. Bacteriol. 154:1347–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.