Abstract

In bacteria like Escherichia coli, the accumulation of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) or its analogs such as α-methyl glucoside-6-phosphate (αMG6P) results in stress that appears in the form of growth inhibition. The small RNA SgrS is an essential part of the response that helps E. coli combat glucose-phosphate stress; the growth of sgrS mutants during stress caused by αMG is significantly impaired. The cause of this stress is not currently known but may be due to either toxicity of accumulated sugar-phosphates or to depletion of metabolic intermediates. Here, we present evidence that glucose-phosphate stress results from depletion of glycolytic intermediates. Addition of glycolytic compounds like G6P and fructose-6-phosphate rescues the αMG growth defect of an sgrS mutant. These intermediates also markedly decrease induction of the stress response in both wild-type and sgrS strains grown with αMG, implying that cells grown with these intermediates experience less stress. Moreover, αMG transport assays confirm that G6P relieves stress even when αMG is taken up by the cell, strongly suggesting that accumulated αMG6P per se does not cause stress. We also report that addition of pyruvate during stress has a novel lethal effect on the sgrS mutant, resulting in cell lysis. The phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) synthetase PpsA, which converts pyruvate to PEP, can confer resistance to pyruvate-induced lysis when ppsA is ectopically expressed in the sgrS mutant. Taken as a whole, these results provide the strongest evidence thus far that depletion of glycolytic intermediates is at the metabolic root of glucose-phosphate stress.

INTRODUCTION

Though sugars are important sources of carbon and energy for bacteria, the excessive accumulation of sugar-phosphates can be detrimental to the cell, preventing growth (1) or causing death (2, 3). For example, in enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli, the intracellular buildup of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) or its analogs such as α-methyl glucoside-6-phosphate (αMG6P) results in a condition called glucose-phosphate stress that manifests as growth inhibition. Glucose and αMG are brought into the cell and phosphorylated by several sugar transporters, including glucose-specific enzyme IICB (EIICBGlc) (the major glucose transporter, encoded by ptsG) and mannose-specific enzyme IIABCD (EIIABCDMan) (the primary mannose transporter, encoded by manXYZ) (4–7). In E. coli, glucose-phosphate stress can be caused either by the addition of analogs like αMG (which can be taken up as αMG6P but not metabolized by the cell) (8) or by a block in glycolysis (for example, a mutation in pgi, which encodes phosphoglucose isomerase, and causes the accumulation of G6P) (9, 10).

While unchecked phosphosugar accumulation impedes growth, E. coli possesses a dedicated regulatory system for dealing with glucose-phosphate stress that consists of the transcriptional regulator SgrR and the small RNA (sRNA) SgrS (8, 11, 12). These two components play an essential role in the response to stress, as highlighted by the fact that sgrR and sgrS mutants are severely inhibited in growth under stress conditions (8, 13). During stress, SgrR, triggered by an unknown signal, activates transcription of sgrS (8, 12). SgrS prevents further uptake of stress-inducing sugar-phosphates, in part by halting production of the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) phosphotransferase system (PTS) transporters EIICBGlc and EIIABCDMan (8, 13–15). These transporters are part of the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system, a phosphorelay cascade that activates these and other sugar transporters and utilizes phosphoenolpyruvate as the initial phosphate donor. The sRNA accomplishes this task through negatively regulating expression of both ptsG and manXYZ mRNAs at the posttranscriptional level. SgrS base pairs with specific regions of the two mRNA transcripts, inhibiting translation by blocking the ribosome binding sites while also leading to degradation via the RNase E degradosome (13–16). SgrS-mRNA base pairing interactions are mediated by the protein Hfq, an RNA chaperone that helps stabilize RNA-RNA interaction (8, 16, 17). SgrS possesses a second function as an mRNA transcript encoding a small protein called SgrT. SgrT restricts the transport of sugars into the cell by inhibiting the activity of EIICBGlc by an unknown mechanism (18, 19).

At a molecular level, SgrS regulation of particular mRNA targets is well understood. In contrast, the cause of glucose-phosphate stress—that is, why cellular growth is inhibited by accumulation of sugar-phosphates—is unknown. It is thought that there are two possible causes. First, the accumulation of sugar-phosphates could itself be toxic to the cell somehow (perhaps due, for example, to the formation of toxic by-products such as methylglyoxal) (10, 11, 20–22). Second, the ensuing disruption of glycolytic metabolism could deplete important intermediates (9–11, 20). There is some evidence to support the latter notion that depletion of glycolytic intermediates is the cause of stress. Studies by H. Aiba's laboratory have suggested that accumulation of G6P or αMG6P is not the only way to induce the stress response. By monitoring levels of the SgrS target, ptsG mRNA, Morita et al. showed that high levels of fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) or fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) (caused by pfkA or fda mutations, respectively) also appear to induce stress, as evidenced by ptsG mRNA degradation under these conditions (10). Further, supplying glycolytic mutants with intermediates downstream of the metabolic block appeared to relieve stress: for instance, even with high G6P levels in a pgi mutant strain, addition of F6P or FBP stops ptsG transcript from being degraded (9). Similarly, in a pfkA mutant with accumulated F6P, addition of FBP (but not F6P) prevents ptsG mRNA degradation (9).

These changes in SgrS target mRNA stability under conditions of altered central metabolism imply that glucose-phosphate stress may be primarily caused by an imbalance in glycolytic intermediates. However, to date, the effects of glycolytic intermediates on induction of the glucose-phosphate stress response have not been directly examined. In the present study, we explore the potential cause of stress by examining the effects of glycolytic intermediates on the ability of an sgrS mutant to recover from αMG-induced stress. We provide the strongest evidence thus far that stress results from the depletion of glycolytic metabolites and not toxicity of glucose-phosphates per se. We find that glycolytic compounds such as G6P and F6P rescue the sgrS mutant from stress even when αMG accumulates, making it unlikely that stress is caused by toxicity of αMG. In contrast, addition of the final glycolytic compound, pyruvate, during stress results in a novel lysis phenotype of the sgrS mutant. Conversion of pyruvate to PEP plays an important part in the resistance to this fatal phenotype: overexpression of the PEP synthetase PpsA, which generates PEP from pyruvate, rescues the sgrS mutant from lysis. Thus, the ability to modulate glycolytic depletion—in particular, the balance of PEP and pyruvate levels—appears to play a key role in recovery from stress, and we discuss the implications of these findings for the physiology of glucose-phosphate stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain construction.

All E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains are derived from the Δlac wild-type strain DJ480 (D. Jin, National Cancer Institute). Strain CS123 carries the sgrS1 mutation and is unable to regulate ptsG or grow under glucose-phosphate stress conditions (23). Deletion-insertion alleles of the mgsA, pgi, ppsA, and uhpT loci were obtained from the Keio collection of single-gene mutations in wild-type background strain BW25113 (24) and contain kanamycin (kan) cassettes flanked by FLP recombination target (FRT) sites. These allele mutations were transferred into the indicated strains (Table 1) by P1 phage transduction, and mutations were verified by PCR using GoTaq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ΔmgsA::FRT-kan-FRT mutant allele was transferred into strains BAH100 (14, 25) and CL109 (26) derivatives of DJ480 and CS123 with an PsgrS-lacZ transcriptional reporter fusion (14, 25) located at the λattB chromosomal locus, to yield strains GR136 and GR137, respectively. ΔuhpT::FRT-kan-FRT and Δpgi::FRT-kan-FRT were similarly moved into strains BAH100 and CL109 to create, respectively, GR130 and GR131 (ΔuhpT::FRT-kan-FRT) and GR132 and GR133 (Δpgi::FRT-kan-FRT). ΔppsA::FRT-kan-FRT was introduced into strains DJ480, CS123, and GR101 (a derivative of CS123 with a pitA::FRT mutation) (26) to construct strains GR162, GR163, and GR164. For ectopic expression of the ppsA gene, wild-type ppsA cloned into the vector pCA24N under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible PT5-lac promoter was obtained from the ASKA library of E. coli open reading frame (ORF) clones in host background strain AG1 (ME5305) (27). Either pCA24N or pCA24N/ppsA was transformed by electroporation into strains CS168 (wild-type) (25) and JH111 (ΔsgrS mutant) (14), which both possess the lacIq tetR Specr allele (encoding the LacIq repressor) at the λattB site.

Table 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| E. coli strain or plasmid | Description or relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DJ480 | MG1655 ΔlacX74 | D. Jin (NCI) |

| CS123 | DJ480 sgrS1G176C,G178C | 23 |

| BAH100 | DJ480 λattB::PsgrS-lacZ | 14, 15 |

| CL109 | CS123 λattB::PsgrS-lacZ | 26 |

| GR100 | CS123 ΔpitA::FRT-kan-FRT | 26 |

| CS168 | DJ480 λattB::lacIq tetR Specr | 25 |

| CS104 | DJ480 ΔsgrS | 19 |

| JH111 | DJ480 ΔsgrS λattB::lacIq tetR Specr | 14 |

| GR101 | CS123 ΔpitA::FRT | 26 |

| GR130 | BAH100 ΔuhpT::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR131 | CL109 ΔuhpT::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR132 | BAH100 Δpgi::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR133 | CL109 Δpgi::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR136 | BAH100 ΔmgsA::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR137 | CL109 ΔmgsA::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR162 | DJ480 ΔppsA::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR163 | CS123 ΔppsA::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| GR164 | GR101 ΔppsA::FRT-kan-FRT | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCA24N | Cmr; lacIq; IPTG-inducible promoter PT5-lac | 27 |

| pCA24N/ppsA | pCA24N + ppsA | 27 |

sgrS1G176C,G178C, sgrS1 with a G-to-C change at position 176 and with a G-to-C change at position 178.

Media and growth conditions.

Bacteria were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (28) at 37°C unless stated otherwise. For experiments examining growth during glucose-phosphate stress, 0.5% αMG was added to induce stress, unless otherwise indicated. For measuring the effects of glycolytic intermediates on growth during stress, 0.1% of the sodium (G6P, F6P, and pyruvate) or barium (FBP) salt of the particular glycolytic compound was added, unless stated otherwise. To maintain plasmids, 25 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol was added to the medium. IPTG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added at a concentration of 0.5 mM to induce expression of the PT5-lac promoter.

Growth curve experiments were performed as described previously (26), with the mentioned modifications. Briefly, overnight cultures of strains were subcultured into new LB medium and normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.02. Once cultures reached an approximate OD600 of 0.1, αMG was added to induce stress. Each culture was then split in two, and the relevant glycolytic compound was added to one of the cultures. Growth was monitored for 7 h via OD600 measurements. When measuring the effects of glycolytic intermediates in growth curve experiments, 0.5% αMG was added before a culture was split into two at an OD600 of about 0.1. For experiments measuring the effects of pyruvate on cell viability during stress, cultures were grown as described above. At 140, 180, and 220 min (before, during, and after suspected cell lysis), OD600 measurements were taken, and the number of viable cells was also determined by dilution plating and counting the number of CFU/milliliter. To measure growth of mgsA and uhpT mutants, qualitative growth at 30°C for 24 h was measured in terms of colony size on solid LB agar medium containing αMG in the presence or absence of G6P or F6P. To examine the effects of ectopic ppsA expression, the colony size of strains was likewise measured during growth on solid LB agar medium with chloramphenicol (to maintain plasmids) and αMG in the presence or absence of pyruvate and with or without IPTG (to induce ppsA expression). For a negative control, strains not under stress (i.e., without αMG or pyruvate) were grown on solid LB medium containing chloramphenicol in either the absence or presence of IPTG.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Wild-type DJ480 (BAH100) and sgrS mutant CS123 (CL109) strains with the PsgrS-lacZ transcriptional fusion were grown overnight and subcultured in fresh LB medium as described above for growth experiments. At an OD600 of approximately 0.1, a lower concentration (0.01%) αMG was used to induce stress, due to the fact that PsgrS-lacZ expression is extremely sensitive and maximum expression is rapidly attained at higher αMG concentrations (25). The culture was then split in two, and a given glycolytic intermediate was added as described above for growth experiments. Samples were taken at 0 and 60 min, and the Miller assay was performed (28). Briefly, samples were suspended in Z-buffer and incubated at 28°C. 2-Nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (4 mg/ml) was used as a substrate, and 1 M Na2CO3 was used to stop the reaction (28).

[14C]αMG transport assays.

Wild-type (DJ480) or sgrS mutant (CS123) strains were grown overnight and subcultured in fresh LB medium as described above for growth experiments. Cultures were then subjected to radiolabeled uptake assays as described previously (29), with the following modifications. Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.1, placed on ice, pelleted at 4°C, washed once with 10 ml of M63 salts, and then washed again in 6 ml of M63 salts. The cells (0.3 ml) were diluted in 0.7 ml of M63 salts and kept on ice until the assay was started. The assay was initiated by shifting cells to room temperature and adding 10 μl of 10 μM radiolabeled [14C]αMG (methyl-α-d-glucopyranoside; 3 μCi/ml; American Radiolabeled Chemicals). Samples were then split in half, and 1.38 μM glucose-6-phosphate was added to one half only. Immediately following addition of [14C]αMG, aliquots of 0.1 ml were withdrawn at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min and then diluted in 4 ml of ice-cold M63 salts plus 0.02% glucose. These samples were vacuum filtered (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 25 mm; 0.45-μm pore size) and washed with 20 ml ice-cold 0.05% NaCl. Radioactivity of the cells was then counted via liquid scintillation.

RESULTS

Early glycolytic intermediates rescue the growth defect of an sgrS mutant during glucose-phosphate stress.

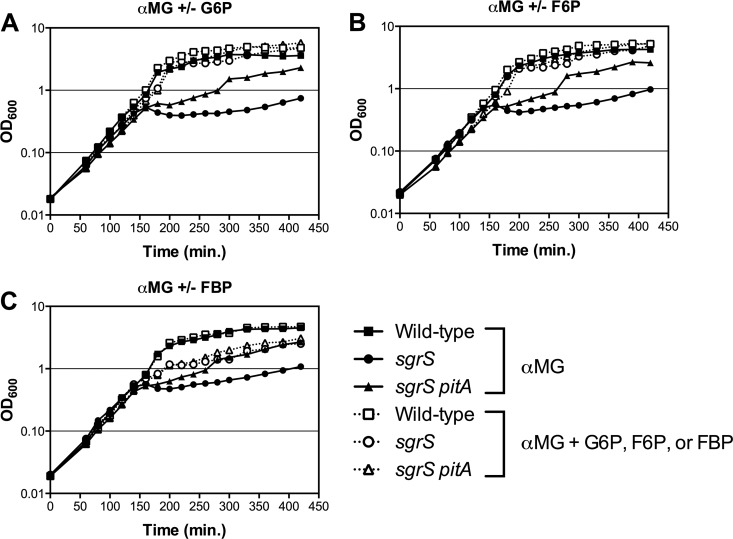

While the cause of glucose-phosphate stress is unknown, it may be due to depletion of glycolytic or other central metabolites downstream of the metabolic block. If this were the case, the addition of glycolytic compounds during stress might help rescue the growth defect of an sgrS mutant, which lacks a wild-type stress response and is unable to recover from stress. To test this hypothesis, we examined growth of an sgrS mutant (23) and wild-type E. coli during stress induced by αMG in the presence and absence of the glycolytic intermediates G6P, F6P, and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP). (These three compounds were chosen for initial study both because they are the first three intermediates in glycolysis and because they are able to be taken up by the cell [9, 21, 30, 31].) When the first glycolytic compound, G6P, was added along with αMG to induce stress, growth of the sgrS mutant was greatly enhanced compared to growth with αMG alone; in fact, the sgrS mutant grew at wild-type levels (Fig. 1A). Similarly, addition of F6P (Fig. 1B) or FBP (Fig. 1C) also resulted in increased growth of the sgrS mutant during stress, although FBP did not rescue growth to wild-type levels. (Wild-type E. coli, possessing a functional stress response, was unaffected by the presence of the glycolytic compounds [Fig. 1].) These results demonstrate that early glycolytic intermediates are in fact able to alleviate the glucose-phosphate stress-associated growth defect of an sgrS mutant.

Fig 1.

Early glycolytic intermediates rescue the α-methyl glucoside (αMG) growth defect of an sgrS mutant. The wild-type (DJ480; squares), sgrS (CS123; circles), and sgrS pitA (GR100; triangles) strains were grown in liquid LB medium with 0.5% αMG to induce glucose-phosphate stress and in either the absence (closed symbols, solid lines) or presence (open symbols, dotted lines) of 0.1% of the glycolytic intermediates glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) (A), fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) (B), or fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) (C). Compounds were added to the indicated cultures at an OD600 of approximately 0.1, and OD600 was monitored over time. One representative experiment is shown (n = 3).

We have previously shown that mutations in pitA, which encodes an inorganic phosphate transporter, partially rescue the αMG growth defect of an sgrS mutant through an unknown mechanism (26) (Fig. 1). The partial rescue of the sgrS growth defect by FBP (Fig. 1C) is reminiscent of the sgrS pitA phenotype. In an effort to learn more about these two forms of stress rescue, we also examined the effects of G6P, F6P, and FBP on the growth of an sgrS pitA mutant (26) during stress. In a manner similar to the sgrS mutant, addition of G6P (Fig. 1A) and F6P (Fig. 1B) further restored the growth of sgrS pitA during stress to wild-type levels. In contrast, FBP had a limited effect on sgrS pitA growth (Fig. 1C), suggesting that FBP addition and the pitA mutation could be rescuing growth of the sgrS mutant by similar means.

Hexose-phosphates such as G6P and F6P are known to enter E. coli through the UhpT transporter via an antiport exchange mechanism with inorganic phosphate (21, 30–32). To verify that growth rescue conferred on the sgrS mutant involves uptake of G6P or F6P via UhpT, the uhpT gene was deleted in the sgrS background and growth of the sgrS uhpT mutant and the sgrS parent (as well as the wild-type strain and uhpT mutants) was monitored on solid LB medium in the presence of αMG with and without G6P or F6P. As expected, both G6P and F6P rescued the growth of the sgrS parent with αMG (as previously seen in Fig. 1) but were unable to rescue the growth defect of the sgrS uhpT mutant, confirming that UhpT-mediated uptake of G6P or F6P is required for rescue of the sgrS growth defect (data not shown). (Both the wild type and the uhpT mutant, possessing a functional stress response, were able to recover from stress regardless of the presence of G6P and F6P [data not shown].) These results indicate that G6P and F6P must be taken up by the cell via the canonical sugar-phosphate transporter in order to mediate growth rescue of sgrS mutants from αMG. Moreover, mutation of pgi (encoding phosphoglucose isomerase, which converts G6P to F6P in the cytoplasm) abrogated rescue of the sgrS mutant by G6P but not F6P (data not shown), implying that metabolism of these compounds is also required for growth rescue.

Early glycolytic intermediates reduce induction of the glucose-phosphate stress response.

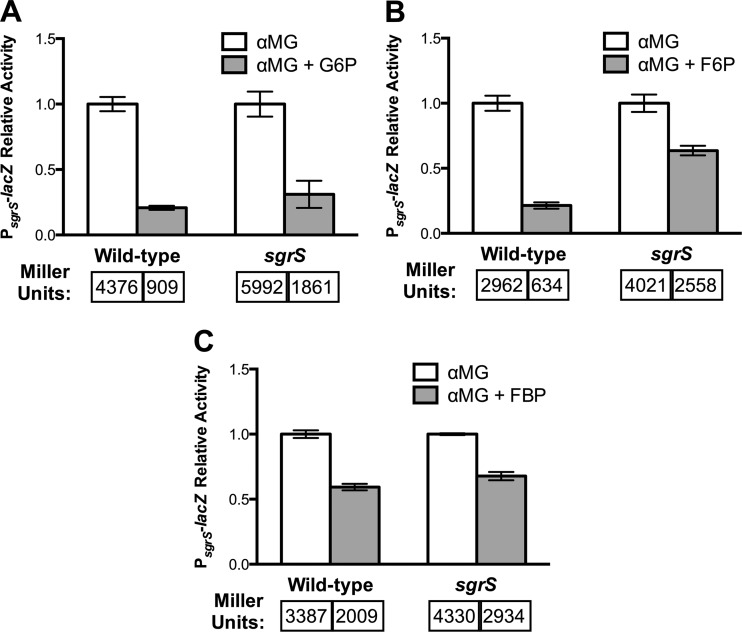

Because expression of sgrS is induced specifically in response to glucose-phosphate stress, it can be used as an indicator for the level of stress experienced by a particular strain. This is exemplified by the fact that sgrS mutants, having an impaired stress response, display a higher level of PsgrS-lacZ induction during stress than the wild type does (25, 26). On the basis of growth rescue of the sgrS mutant by addition of G6P, F6P, and FBP, we predicted this relief from stress would be further evidenced by a reduction in PsgrS-lacZ expression under stress conditions. To test this prediction, we measured PsgrS-lacZ activity in both the wild type and the sgrS mutant during αMG-induced stress in the presence and absence of the intermediates. The addition of G6P resulted in a drastic reduction in the level of PsgrS-lacZ induction during stress for both the wild-type strain and the sgrS mutant compared to growth with αMG alone (Fig. 2A). The addition of F6P also led to a decrease in PsgrS-lacZ expression for both the wild type and the sgrS mutant, although the effect was more pronounced for the wild type (Fig. 2B). Both strains exhibited lower levels of PsgrS-lacZ activity when FBP was present; in the case of sgrS, the effect of FBP was similar to that of F6P, while for the wild type, FBP was less effective than G6P and F6P at reducing PsgrS-lacZ induction (Fig. 2C). Altogether, the results indicate that early glycolytic intermediates reduced the level of stress experienced by both the wild type and the sgrS mutant in the presence of αMG, which is consistent with their rescue of the sgrS mutant growth defect (Fig. 1). These results also further support the notion that depletion of glycolytic intermediates leads to glucose-phosphate stress (and thus induction of the stress response).

Fig 2.

Effects of early glycolytic intermediates on the induction of PsgrS-lacZ expression during growth in αMG. Wild-type (BAH100) and sgrS (CL109) strains with chromosomal PsgrS-lacZ fusions were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of approximately 0.1, at which point 0.01% αMG was added in the absence (white bars) or presence (gray bars) of 0.1% of the glycolytic intermediates G6P (A), F6P (B), or FBP (C). β-Galactosidase activity was measured at 60 min after the addition of αMG (and glycolytic intermediates, where relevant). Specific activities were normalized to growth in αMG alone to determine the relative activity reported. Specific activities (Miller units) are reported below the bars. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

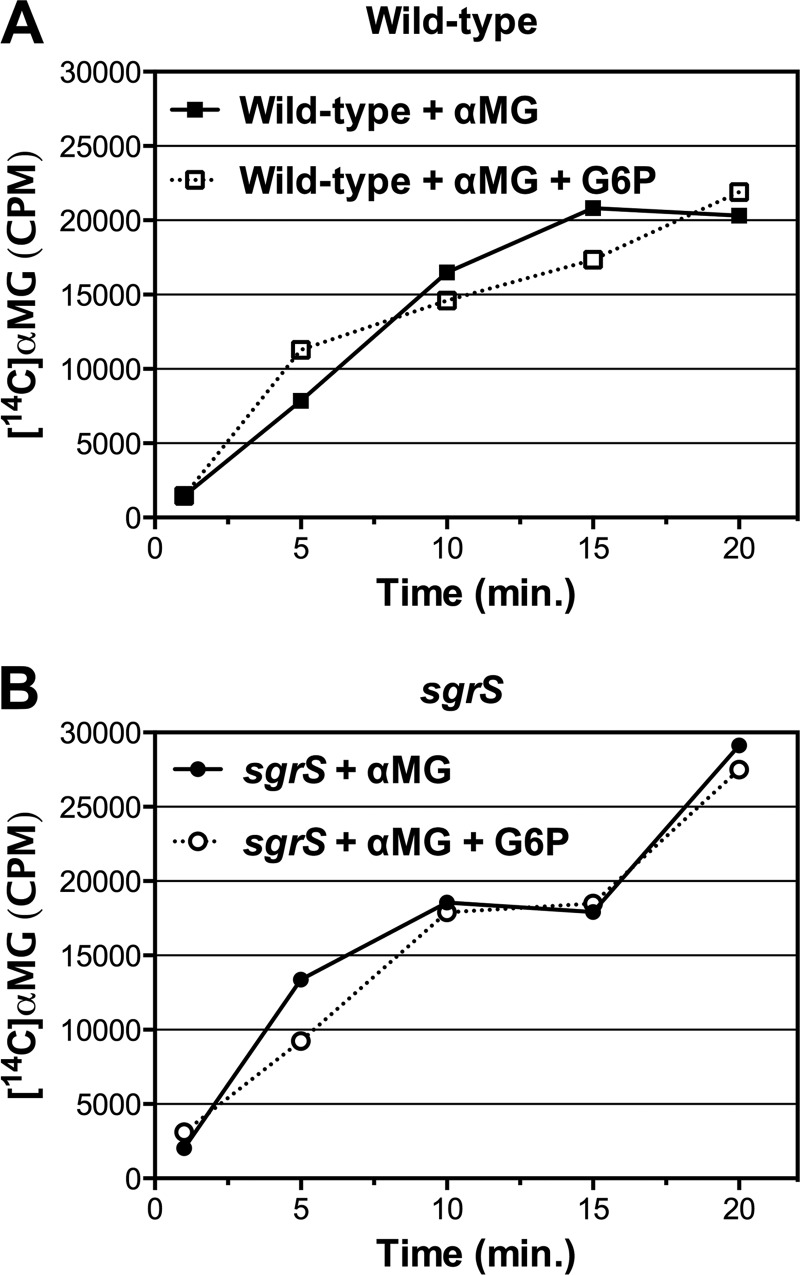

Glucose-6-phosphate does not affect cellular αMG uptake.

Our data suggest that the glycolytic intermediates themselves are able to alleviate αMG-induced stress through bypassing the glycolytic block (Fig. 1 and 2; data not shown). However, it was also possible that the intermediates reduce stress by somehow decreasing uptake of αMG. This was unlikely, given that αMG enters the cell primarily via EIICBGlc (5, 7), whereas the intermediates (at least G6P and F6P) enter via UhpT (21, 30–32). Nevertheless, to rule out this possibility, we monitored uptake of 14C-radiolabeled αMG by both the wild type and the sgrS mutant in the presence and absence of G6P. As expected, [14C]αMG uptake was not affected by G6P for either the wild-type strain or the sgrS mutant (Fig. 3), supporting the conclusion that reduced stress is not the result of lower levels of αMG6P accumulating in the cell. Taken together, the results in Fig. 1 to 3 demonstrate that intermediates early in the glycolytic pathway are able to relieve glucose-phosphate stress. Moreover, given that G6P does not decrease the uptake of the stressor αMG (Fig. 3), these observations also support the notion that glucose-phosphate stress induced by αMG is due to depletion of glycolytic intermediates and not toxicity of accumulated αMG6P per se.

Fig 3.

Effects of the glycolytic intermediate glucose-6-phosphate on the uptake of [14C]αMG. (A) Wild-type (DJ480; squares) or (B) sgrS (CS123; circles) strains were grown in liquid LB medium to an OD600 of 0.1, at which point [14C]αMG (10.0 μM; 3 μCi per sample) was added in either the absence (closed symbols, solid lines) or presence (open symbols, dotted lines) of G6P (1.38 μM). Cellular uptake of the radioactive [14C]αMG was measured at the indicated times. One representative example is shown (n = 3).

sgrS exhibits a novel lethal phenotype following the addition of pyruvate during glucose-phosphate stress.

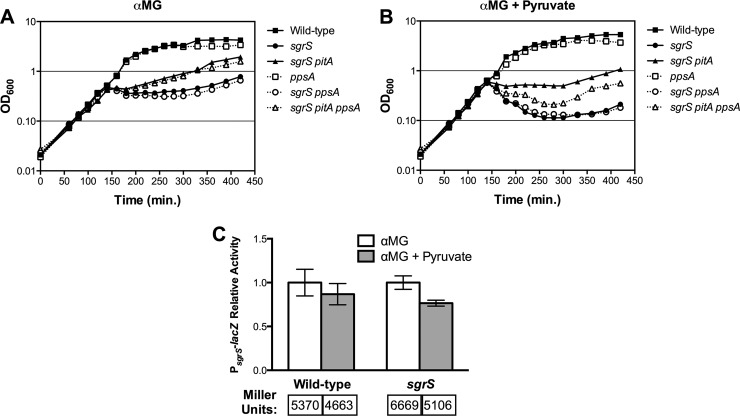

It is clear that upstream glycolytic compounds rescue the sgrS mutant from stress with αMG. To begin to examine the effects of intermediates lower in the pathway, we monitored the growth of the wild-type strain and of the sgrS and sgrS pitA mutants during αMG-induced stress in the absence (Fig. 4A) and presence (Fig. 4B) of pyruvate, the final compound in glycolysis. (The effects of other glycolytic compounds such as PEP, the penultimate glycolytic compound, were not examined, as E. coli is not known to possess transporters for PEP or the other untested glycolytic compounds.) The presence of pyruvate did not affect the growth of the wild type during stress, as was seen for the other intermediates tested (compare Fig. 4A and B). However, in contrast to other glycolytic intermediates, the addition of pyruvate to sgrS mutant cells during stress resulted in a dramatic decrease in the OD600 reminiscent of cell death (Fig. 4B). (As observed previously, growth of the sgrS mutant with only αMG inhibited growth but did not result in decreased OD600 [Fig. 4A].) Unlike the sgrS mutant, the sgrS pitA mutant largely was resistant to the pyruvate-induced decrease in OD600, although the OD600 at later time points was slightly lower in the presence of both pyruvate and αMG (Fig. 4B) compared to αMG alone (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Effects of pyruvate on growth and sgrS expression during glucose-phosphate stress. (A and B) Growth of wild-type (DJ480), sgrS (CS123), sgrS pitA (GR101), ppsA (GR162), sgrS ppsA (GR163), and sgrS pitA ppsA (GR164) strains. Strains were grown in liquid LB medium with 0.5% αMG to induce glucose-phosphate stress in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 0.1% pyruvate. Compounds were added to the indicated cultures at an OD600 of approximately 0.1, and OD600 was monitored over time. One representative experiment is shown (n = 3). (C) Expression of PsgrS-lacZ during growth with αMG in the absence and presence of pyruvate. Wild-type (BAH100) and sgrS (CL109) strains with chromosomal PsgrS-lacZ fusions were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of approximately 0.1, at which point 0.01% αMG was added with 0.1% pyruvate or without pyruvate. Specific activities were normalized to growth in αMG alone to determine the relative activity reported. Specific activities (Miller units) are reported below the bars. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Early glycolytic compounds alleviate stress as illustrated both by improved sgrS growth (Fig. 1) and decreased stress response induction (Fig. 2). Because pyruvate has the opposite effect on sgrS growth during stress, we also measured its effect on the level of stress experienced by the wild type and sgrS mutant in terms of PsgrS-lacZ induction. Unlike other intermediates of glycolysis, the addition of pyruvate to both the wild-type and sgrS cultures during stress had little to no effect on PsgrS-lacZ expression (Fig. 4C).

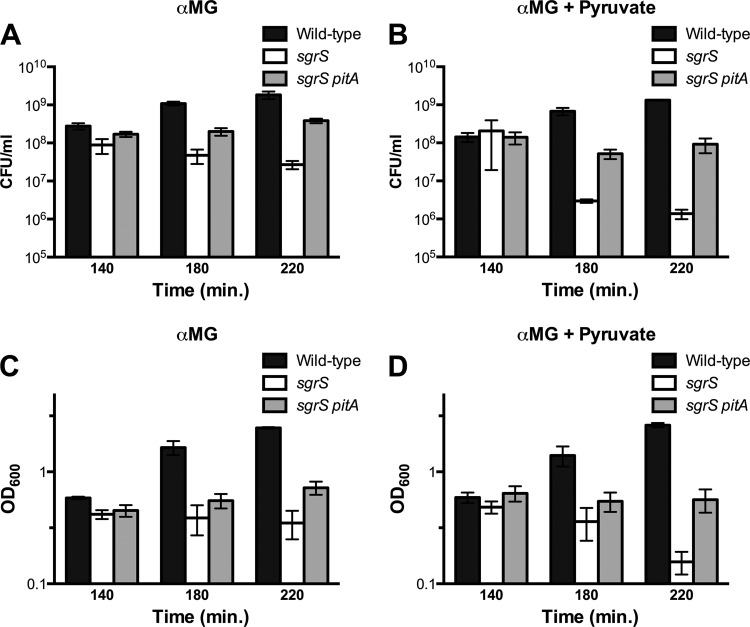

To determine whether the striking decrease in OD600 of the sgrS mutant grown with pyruvate and αMG was in fact due to cell death, we measured both cell viability (in CFU/ml) and the OD600 of the wild-type, sgrS, and sgrS pitA cultures grown with αMG with or without pyruvate. On the basis of the results shown in Fig. 4, we chose to monitor growth before (140 min), during (180 min), and after (220 min) the decrease in OD600 of the sgrS mutant. At 140 min (prior to the observed drop in OD600), all three strains displayed roughly equivalent CFU/ml and OD600 values, as expected (Fig. 5). Corresponding with the drop in OD600 (at 180 and 220 min [Fig. 5D]), the sgrS mutant grown with pyruvate and αMG exhibited over a 10-fold decrease in the CFU/ml (Fig. 5B). This was in contrast to sgrS mutant growth with only αMG, which was relatively stable (Fig. 5A and C). These results confirm that the addition of pyruvate during glucose-phosphate stress is lethal to sgrS mutant cells. In addition, the combination of decreased OD600 and CFU/ml is consistent with lysis of the sgrS mutant. As expected, wild-type cells continued growing after challenge with αMG regardless of the presence of pyruvate, as evidenced by increases in both OD600 (Fig. 5D versus C) and CFU/ml (Fig. 5B versus A). In addition, growth of the sgrS pitA mutant with or without pyruvate was largely stable over time for both OD600 (Fig. 5D versus C) and CFU/ml (Fig. 5B versus A), confirming its resistance to pyruvate-induced lysis.

Fig 5.

The addition of pyruvate results in loss of sgrS mutant viability during growth in αMG. (A and B) Growth of the wild-type (DJ480), sgrS (CS123), and sgrS pitA (GR100) strains in liquid LB medium. At an OD600 of approximately 0.1, 0.5% αMG was added to induce glucose-phosphate stress either without pyruvate (A) or with 0.1% pyruvate (B). Samples were taken at 140, 180, and 220 min, and the number of CFU/ml was determined. (C and D) Corresponding OD600 values for the cultures described above in panels A and B grown with αMG and either without pyruvate (C) or with pyruvate (D). OD600 values were measured at 140-, 180-, and 220-min time points. In each graph, error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

In exploring potential causes of sgrS mutant lysis in the presence of pyruvate and αMG, we noted that the loss in cell viability is reminiscent of that caused by accumulation of the toxic metabolite methylglyoxal (21). Methylglyoxal is produced from the glycolytic intermediate dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by the methylglyoxal synthase MgsA, and MgsA activity is stimulated by DHAP (22). Unregulated transport of hexose-phosphates (such as G6P and F6P) due to UhpT overexpression results in toxic levels of methylglyoxal, presumably caused by increased levels of DHAP (21, 22). It was possible that the combination of αMG and pyruvate somehow increased methylglyoxal production via MgsA, leading to the observed decrease in sgrS viability. We introduced an mgsA deletion mutation into the sgrS mutant background, reasoning that if mgsA were responsible for the lethal sgrS phenotype, deleting it should restore viability in the presence of αMG and pyruvate. However, growth of the sgrS mgsA mutant in the presence of pyruvate with αMG resulted in cell death similar to that of the sgrS parent (data not shown), indicating that methylglyoxal is not the cause of the lethality.

ppsA, which encodes PEP synthetase, contributes to sgrS pitA resistance to pyruvate-induced lysis during glucose-phosphate stress.

While pyruvate causes lysis of the sgrS mutant during stress, the sgrS pitA mutant is resistant to this lysis (Fig. 4 and 5). We observed previously that expression of ppsA, which encodes the PEP synthetase capable of converting pyruvate into PEP, is increased by approximately 2-fold in the sgrS pitA mutant compared to the sgrS parent during growth with αMG (26). Since pyruvate is somehow detrimental to growth of the sgrS mutant in αMG, we hypothesized that increased conversion of pyruvate to PEP by PpsA could allow the sgrS pitA mutant to resist lysis. To determine whether ppsA is required for sgrS pitA resistance to lysis, a ppsA insertion-deletion mutation (24) was introduced into the wild-type, sgrS, and sgrS pitA strains. Growth of the ppsA mutants and their parent strains in media with αMG and with (Fig. 4B) or without (Fig. 4A) pyruvate was then monitored. Unlike its sgrS pitA parent, the sgrS pitA ppsA mutant exhibited a large decrease in OD600 when grown with pyruvate during stress, demonstrating that ppsA plays a role in sgrS pitA resistance to lysis by pyruvate (Fig. 4B). However, the pyruvate growth defect of the sgrS pitA ppsA mutant was not as severe as that of the sgrS mutant, implying that other factors may contribute to sgrS pitA resistance (Fig. 4B). The ppsA mutation did not appear to contribute to sgrS pitA suppression in αMG alone, as the sgrS pitA ppsA mutant grows approximately as well as its sgrS pitA parent (Fig. 4A). The deletion of ppsA in the wild-type and sgrS backgrounds did not have an effect on growth during stress regardless of whether pyruvate was present (Fig. 4B) or absent (Fig. 4A).

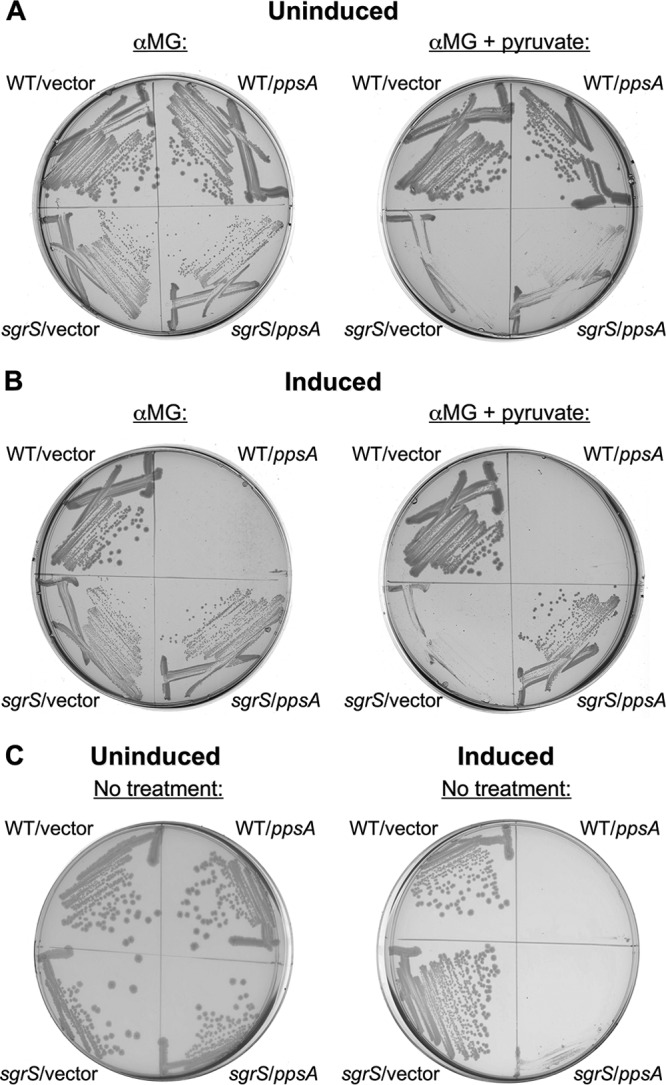

Overexpression of ppsA rescues sgrS from pyruvate-induced lysis during glucose-phosphate stress.

Increased expression of ppsA at least partly confers resistance of the sgrS pitA mutant to pyruvate-mediated lysis. Therefore, we hypothesized that ectopic expression of ppsA may also rescue sgrS from lysis by converting pyruvate into PEP. To test this, wild-type ppsA under the control of an IPTG-inducible Plac promoter in vector pCA24N (27) was introduced into the wild type (25) and ΔsgrS (14) derivatives. As previously observed (Fig. 4), the sgrS strain carrying a vector control was much more severely impaired in growth in the presence of both αMG and pyruvate (Fig. 6B, “sgrS/vector” on the right plate) than when grown with αMG alone (Fig. 6B, “sgrS/vector” on the left plate). On the other hand, the induction of Plac-ppsA expression restored the ability of sgrS to grow in the presence of αMG and pyruvate (Fig. 6B, “sgrS/ppsA” on the right plate) (although not to wild-type levels), thereby confirming that conversion of pyruvate to PEP by PpsA can prevent pyruvate-induced lysis. Interestingly, while deletion of ppsA did not further impair growth of the sgrS strain with αMG alone (Fig. 4A, compare the growth curves of sgrS and sgrS ppsA strains), ectopic expression of ppsA did appear to slightly improve growth of the sgrS mutant during αMG (only) stress (Fig. 6B, compare “sgrS/ppsA” and “sgrS/vector” on the left plate). As expected, the uninduced wild-type controls (containing the vector only or uninduced ppsA) grew well on αMG with (Fig. 6A) or without (Fig. 6A) pyruvate, while the sgrS strains without ppsA induction were defective in growth (Fig. 6A). The lack of growth in the wild-type strain overexpressing ppsA (Fig. 6B) is consistent with previous studies showing that while moderate levels of ppsA expression can improve the growth of wild-type E. coli, an excessive increase in expression inhibits growth (33). Indeed, during growth in the absence of glucose-phosphate stress (i.e., in media lacking either αMG or pyruvate), both wild-type and sgrS strains overexpressing ppsA exhibited this growth defect (Fig. 6C, compare the right plate to the left plate). In sum, mutating ppsA promotes pyruvate-induced lysis of the sgrS pitA mutant (Fig. 4), and overexpressing ppsA rescues sgrS from lysis (Fig. 6). These two results together demonstrate that pyruvate-induced lysis of sgrS during glucose-phosphate stress can be alleviated by conversion of pyruvate to PEP via PpsA. Collectively, the findings presented in this study are consistent with the notion that the depletion of glycolytic intermediates contributes to glucose-phosphate stress (Fig. 1 to 3), and the balance of PEP and pyruvate in particular is likely very important to survival during stress (Fig. 4 to 6).

Fig 6.

Ectopic expression of ppsA rescues sgrS from pyruvate-induced lysis during growth in αMG. (A and B) Growth of wild-type (CS168) and sgrS (JH111) strains carrying either vector pCA24N (“WT/vector” and “sgrS/vector”, respectively) or pCA24N containing a wild-type copy of ppsA (“WT/ppsA” and “sgrS/ppsA”, respectively) under the control of the Plac promoter. Strains were grown for 24 h on solid LB medium with either 0.5% αMG only (left plate) or 0.5% αMG plus 0.1% pyruvate (right plate), and Plac expression was either uninduced (A) or induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (B). (C) Growth of the strains described above for panels A and B for 24 h on solid LB medium only (i.e., untreated with αMG and pyruvate). Plac expression was either uninduced (left plate) or induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (right plate). In each case, one representative example is shown (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Stress resulting from inhibition of the glycolytic pathway and the ensuing accumulation of sugar-phosphates was first described decades ago. In spite of recent advances in our understanding of the targets and molecular mechanisms of the regulatory response to glucose-phosphate stress, the metabolic root of stress—in other words, the reason why it is stressful for cells to accumulate glucose-phosphates—has remained elusive. It has been posited that either the toxicity of accumulating sugar-phosphates or the depletion of glycolytic or other metabolic intermediates may lead to stress (9–11, 20). In this study, we present the most definitive evidence thus far that glucose-phosphate stress likely results from depletion of glycolytic intermediates, and not toxicity related to accumulated sugar-phosphates. We demonstrate that addition of early intermediates in glycolysis (G6P, F6P, or FBP) alleviates stress induced by αMG, both in terms of improved growth of an sgrS mutant during stress (Fig. 1) and reduced stress response induction for both the wild-type strain and the sgrS mutant (Fig. 2). These findings are in keeping with the manner in which glucose-phosphate stress is elicited: if the inability to operate the glycolytic pathway leads to depletion of its intermediates, circumventing that block (e.g., by adding back those intermediates) is essential in order to recover from stress. Importantly, the presence of G6P did not decrease the cellular uptake of αMG (Fig. 3). To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration thus far that the stress-associated growth defect can be rescued even under conditions where the stressor αMG accumulates in the cell. These results strongly support the idea that metabolic depletion of glycolytic intermediates, and not toxicity of αMG6P per se, is the underlying cause of glucose-phosphate stress.

These results are in agreement with previous findings that implied that depletion of glycolytic intermediates could be the cause of stress. Work by H. Aiba's laboratory suggested that glucose-phosphate stress induced in another manner (namely, sugar-phosphates accumulating due to mutations in glycolytic genes such as pgi or pfkA) can also be ameliorated by the addition of compounds downstream of the metabolic block (such as, respectively, F6P or FBP) (9, 10). Our current study demonstrates that glycolytic intermediates yield a dramatic improvement in growth of stressed sgrS mutants, which are defective for the stress response and strongly growth inhibited by the glucose analog αMG. Taken together, both Aiba's work and the current study are consistent with the notion that glucose-phosphate stress induced by two independent means (mutational block and glucose analog addition) is caused by glycolytic intermediate depletion. While both studies provide strong support for depletion causing stress, we nevertheless cannot formally rule out the possibility that glycolytic depletion contributes to glucose-phosphate stress by exacerbating the toxicity of sugar-phosphates through some as-yet-unknown mechanism.

While all three early glycolytic intermediates rescued sgrS mutants from stress, the extent of rescue varied. While G6P and F6P fully rescued growth in the presence of αMG, FBP exhibited a partial rescue of growth (Fig. 1). Similarly, G6P appeared to reduce stress-associated PsgrS-lacZ induction in the sgrS mutant better than F6P or FBP did, while G6P and F6P relieved stress in wild-type cells to a greater extent than FBP did (Fig. 2). To a certain extent, the intermediates appear to rescue to a degree corresponding to their position in glycolysis: G6P rescued better than F6P, which rescued better than FBP. While it is possible that these differences are due to efficiency of transport, it could also be that early glycolytic intermediates more efficiently reroute carbon metabolism to other pathways. For example, G6P feeds directly into both glycolysis and the pentose-phosphate pathway, and this may be beneficial for restoring the balance of central metabolites in stressed cells. Consistent with this idea, mutating either pgi (which encodes the first enzyme in the glycolytic pathway) (data not shown) or zwf (which encodes glucose 6-phosphate-1-dehydrogenase, the first enzyme in the pentose-phosphate pathway) (data not shown) in the sgrS background decreased rescue by G6P during growth with αMG. This is consistent with both glycolysis and pentose phosphate cycle being important for stress relief via G6P.

In striking contrast to early glycolytic metabolites, the addition of pyruvate during αMG-induced stress causes a novel lethal phenotype of an sgrS mutant, resulting in lysis instead of the growth inhibition typically observed during glucose-phosphate stress (Fig. 4 and 5). (Wild-type E. coli, possessing a functional stress response, was not affected by pyruvate.) We demonstrate in two different ways that the generation of PEP from pyruvate is an effective mechanism to resist lysis. First, ectopic overexpression of ppsA in the sgrS mutant prevented lysis in the presence of pyruvate and αMG (Fig. 6B). Second, a mutation in pitA, which partially suppresses the αMG growth defect of the sgrS strain (26) (Fig. 4), also promoted survival in the presence of αMG and pyruvate (Fig. 4). During stress, ppsA expression is increased approximately 2-fold in the sgrS pitA mutant compared to its sgrS parent (26), and here we show that conversion of pyruvate to PEP by PpsA was at least partially responsible for the increased pyruvate resistance of the sgrS pitA mutant (Fig. 4). This was demonstrated by decreased resistance to lysis in the sgrS pitA ppsA mutant compared to the sgrS pitA parent (Fig. 4). While ppsA expression alleviates pyruvate-induced lysis during glucose-phosphate stress, the cause of lysis is unclear. Pyruvate addition during stress may somehow lead to further depletion of glycolytic intermediates, perhaps PEP in particular, and further exacerbate stress. According to independent RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and microarray analyses, expression of ppsA is increased approximately 3- to 4-fold when wild-type E. coli is grown in the presence of αMG (M. Bobrovskyy, B. Tjaden, and C. Vanderpool, unpublished data), supporting our data that increasing PEP production may be an important strategy for recovery from stress.

If glucose-phosphate stress is related to the depletion of PEP levels, why would PEP depletion be stressful to the cell? PEP is essential for numerous metabolic functions, particularly in central carbon metabolism. With its dual roles in glycolysis and as the initiator of the PTS phosphorelay, PEP is the molecule that most directly links sugar transport to sugar catabolism. It is uniquely positioned to communicate information between the two; indeed, when PEP levels are increased via ppsA overexpression, there is some evidence that PEP is able to inhibit the activity of enzymes early in glycolysis such as Pgi (34). The uncurbed accumulation of sugar-phosphates (for example, in an sgrS mutant exposed to αMG) could therefore decrease the amount of available PEP in at least two distinct ways. First, the glycolytic block caused by nonmetabolizable αMG6P could prevent PEP formation during glycolysis. Second, the inability of the sgrS mutant to stop the activity of PTS sugar transporters EIICBGlc (encoded by ptsG) and EIIABCDMan (encoded by manXYZ) would further deplete PEP by its conversion to pyruvate during the PTS phosphorelay. This might also explain why ppsA expression is increased in the wild-type strain during stress caused by αMG. Furthermore, this depletion of PEP/generation of pyruvate could be why ectopic ppsA expression appears to help the sgrS mutant growth during αMG-induced stress (Fig. 6C) and why “spiking” the culture with even more pyruvate could stress the sgrS mutant to the point of lethality (Fig. 4 and 5). Adding pyruvate when PEP is already depleted may also exacerbate stress because of the role that the ratio of PEP to pyruvate plays in sugar transport. The ratio affects the activity of the EIICBGlc transporter by modulating the phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc (encoded by crr), the glucose-specific member of the PTS relay responsible for phosphorylating and activating EIICBGlc (35–37). A lower PEP-to-pyruvate ratio correlates with dephosphorylated EIIA and increased EIIAGlc transport activity (35). Again, the inability of the sgrS mutant to curb αMG transport would decrease PEP and increase pyruvate, and this would be further compounded by the addition of exogenous pyruvate.

While most types of sugar-phosphate stress are not well understood, other studies support a common theme of metabolite depletion as an underlying cause. The glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose renders E. coli unable to grow with fructose as the sole carbon source. This growth inhibition appears to be due to depleted PEP levels, as 2-deoxyglucose competes with fructose for PEP utilization to drive PTS transport, but unlike fructose, does not regenerate PEP via glycolysis because it cannot be metabolized by the cell (38). In fact, constitutive expression of the glyoxylate shunt is thought to suppress the growth defects of both in pfkA (which accumulates F6P) and ppsA mutants by generating PEP (39, 40). Similarly, galE mutants accumulate high levels of UDP-galactose and are defective in growth. However, this growth inhibition was found to be due not to the accumulated sugar-phosphates, but to depletion of UTP, which is required for formation of CTP. Therefore, supplying the galE mutant with pyrimidines was sufficient to restore growth even during growth in the presence of the sugar-phosphate (41).

Another recent study from our laboratory (an accompanying article [42]) looked at questions surrounding glucose-phosphate stress metabolism and physiology from a different angle. This study determined that the requirement for SgrS regulation of different targets during glucose-phosphate stress varies under different nutritional conditions. The results demonstrate clearly that stress-associated growth inhibition is more severe when cells are cultured in nutrient-poor minimal media than in rich media. Essentially, when stress is more severe (i.e., in minimal media), SgrS must regulate additional targets in order to promote stress recovery. Particularly relevant to our current study, the nutritional study showed that sgrS cells stressed in minimal media can be partially rescued by addition of amino acids. Rescue of sgrS mutant growth by amino acids differs from rescue by upper glycolytic intermediates in that it occurs only after a long lag (42), in contrast to the immediate growth recovery promoted by glycolytic intermediates (Fig. 1). This could be because conversion of amino acids to glycolytic intermediates would require induction of the full gluconeogenesis pathway, and the lag in rescue by amino acids may represent the time it takes for cells to produce sufficient gluconeogenic enzymes to convert amino acids to PEP and other necessary intermediates.

The genetic and phenotypic evidence presented in this study reveals that the stress associated with accumulation of glucose-phosphates has a basis in depletion of glycolytic intermediates, and possibly PEP in particular. Nevertheless, given that depletion of PEP seems to be the likely cause of stress, the ability to balance the ratio of PEP to pyruvate in the cell may be the key to the metabolic recovery from glucose-phosphate stress. Thus, future studies directly measuring the levels of glycolytic intermediates and metabolic flux during stress, as well as genetic manipulation of other pathways related to PEP and pyruvate metabolism, could provide additional insight into how cells successfully overcome glucose-phosphate stress. Such studies could also provide clues as to the unknown signal that activates SgrR and the stress response, which has been hypothesized to be a small molecule related to glycolysis (12). Since the ratio of PEP to pyruvate appears to be at the heart of glucose-phosphate stress, the levels of PEP, which are uniquely positioned to communicate between glucose transport and metabolism, would make an ideal method for sensing and responding to stress. Moreover, given that the ways in which stress is induced in the laboratory (i.e., glycolytic mutations and glucose analogs) are relatively artificial, further characterization of the metabolic root of stress may ultimately lead to a better understanding of the elusive roles of the glucose stress response in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the E. coli National BioResource Project at the National Institute of Genetics (Japan) for supplying us with Keio collection mutants and ASKA plasmids. We are also very appreciative of assistance from members of C. K. Vanderpool's laboratory, and we particularly want to thank Divya Balasubramanian for invaluable technical support.

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society Research scholar grant ACS2008-01868 and National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM092830. G. R. Richards was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health award F32GM096509.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Englesberg E, Anderson RL, Weinberg R, Lee N, Hoffee P, Huttenhauer G, Boyer H. 1962. l-Arabinose-sensitive, l-ribulose 5-phosphate 4-epimerase-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 84:137–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irani MH, Maitra PK. 1977. Properties of Escherichia coli mutants deficient in enzymes of glycolysis. J. Bacteriol. 132:398–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarmolinsky MB, Wiesmeyer H, Kalckar HM, Jordan E. 1959. Hereditary defects in galactose metabolism in Escherichia coli mutants. II. Galactose-induced sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 45:1786–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott J, Arber W. 1978. E. coli K-12 pel mutants, which block phage lambda DNA injection, coincide with ptsM, which determines a component of a sugar transport system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 161:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meadow ND, Fox DK, Roseman S. 1990. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: glycose phosphotransferase system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59:497–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erni B, Zanolari B, Kocher HP. 1987. The mannose permease of Escherichia coli consists of three different proteins. Amino acid sequence and function in sugar transport, sugar phosphorylation, and penetration of phage lambda DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 262:5238–5247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson PJ, Giddens RA, Jones-Mortimer MC. 1977. Transport of galactose, glucose and their molecular analogues by Escherichia coli K12. Biochem. J. 162:309–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanderpool CK, Gottesman S. 2004. Involvement of a novel transcriptional activator and small RNA in post-transcriptional regulation of the glucose phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1076–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimata K, Tanaka Y, Inada T, Aiba H. 2001. Expression of the glucose transporter gene, ptsG, is regulated at the mRNA degradation step in response to glycolytic flux in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 20:3587–3595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita T, El-Kazzaz W, Tanaka Y, Inada T, Aiba H. 2003. Accumulation of glucose 6-phosphate or fructose 6-phosphate is responsible for destabilization of glucose transporter mRNA in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 278:15608–15614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanderpool CK. 2007. Physiological consequences of small RNA-mediated regulation of glucose-phosphate stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderpool CK, Gottesman S. 2007. The novel transcription factor SgrR coordinates the response to glucose-phosphate stress. J. Bacteriol. 189:2238–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita T, Mochizuki Y, Aiba H. 2006. Translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by bacterial small noncoding RNAs in the absence of mRNA destruction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:4858–4863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice JB, Vanderpool CK. 2011. The small RNA SgrS controls sugar-phosphate accumulation by regulating multiple PTS genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:3806–3819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamoto H, Koide Y, Morita T, Aiba H. 2006. Base-pairing requirement for RNA silencing by a bacterial small RNA and acceleration of duplex formation by Hfq. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1013–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morita T, Maki K, Aiba H. 2005. RNase E-based ribonucleoprotein complexes: mechanical basis of mRNA destabilization mediated by bacterial noncoding RNAs. Genes Dev. 19:2176–2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang A, Wassarman KM, Rosenow C, Tjaden BC, Storz G, Gottesman S. 2003. Global analysis of small RNA and mRNA targets of Hfq. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1111–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanderpool CK, Balasubramanian D, Lloyd CR. 2011. Dual-function RNA regulators in bacteria. Biochimie 93:1943–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadler CS, Vanderpool CK. 2007. A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:20454–20459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards GR, Vanderpool CK. 2011. Molecular call and response: the physiology of bacterial small RNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1809:525–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadner RJ, Murphy GP, Stephens CM. 1992. Two mechanisms for growth inhibition by elevated transport of sugar phosphates in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2007–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopper DJ, Cooper RA. 1971. The regulation of Escherichia coli methylglyoxal synthase; a new control site in glycolysis? FEBS Lett. 13:213–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadler CS, Vanderpool CK. 2009. Characterization of homologs of the small RNA SgrS reveals diversity in function. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:5477–5485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun Y, Vanderpool CK. 2011. Regulation and function of Escherichia coli sugar efflux transporter A (SetA) during glucose-phosphate stress. J. Bacteriol. 193:143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards GR, Vanderpool CK. 2012. Induction of the Pho regulon suppresses the growth defect of an Escherichia coli sgrS mutant, connecting phosphate metabolism to the glucose-phosphate stress response. J. Bacteriol. 194:2520–2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. 2005. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12:291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Alles LF, Zahn A, Erni B. 2002. Sugar recognition by the glucose and mannose permeases of Escherichia coli. Steady-state kinetics and inhibition studies. Biochemistry 41:10077–10086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonna LA, Ambudkar SV, Maloney PC. 1988. The mechanism of glucose 6-phosphate transport by Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:6625–6630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maloney PC, Ambudkar SV, Anatharam V, Sonna LA, Varadhachary A. 1990. Anion-exchange mechanisms in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 54:1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winkler HH. 1966. A hexose-phosphate transport system in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 117:231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chao YP, Patnaik R, Roof WD, Young RF, Liao JC. 1993. Control of gluconeogenic growth by pps and pck in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6939–6944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogawa T, Mori H, Tomita M, Yoshino M. 2007. Inhibitory effect of phosphoenolpyruvate on glycolytic enzymes in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 158:159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogema BM, Arents JC, Bader R, Eijkemans K, Yoshida H, Takahashi H, Aiba H, Postma PW. 1998. Inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli by non-PTS substrates: the role of the PEP to pyruvate ratio in determining the phosphorylation state of enzyme IIAGlc. Mol. Microbiol. 30:487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barabote RD, Saier MH., Jr 2005. Comparative genomic analyses of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:608–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tchieu JH, Norris V, Edwards JS, Saier MH., Jr 2001. The complete phosphotranferase system in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:329–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornberg H, Lambourne LT. 1994. The role of phosphoenolpyruvate in the simultaneous uptake of fructose and 2-deoxyglucose by Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:11080–11083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roehl RA, Vinopal RT. 1976. Lack of glucose phosphotransferase function in phosphofructokinase mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 126:852–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinopal RT, Fraenkel DG. 1974. Phenotypic suppression of phosphofructokinase mutations in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of the glyoxylate shunt. J. Bacteriol. 118:1090–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ, Trostel A, Le P, Harinarayanan R, Fitzgerald PC, Adhya S. 2009. Cellular stress created by intermediary metabolite imbalances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19515–19520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Vanderpool CK. 2013. Physiological consequences of multiple-target regulation by the small RNA SgrS in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 195:4804–4815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]