Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis comprises two genotypically defined groups, known as the cattle (C) and sheep (S) groups. Recent studies have reported phenotypic differences between M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis groups C and S, including growth rates, infectivity for macrophages, and iron metabolism. In this study, we investigated the genotypes and biological properties of the virulence factor heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin (HBHA) for both groups. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HBHA is a major adhesin involved in mycobacterium-host interactions and extrapulmonary dissemination of infection. To investigate HBHA in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, we studied hbhA polymorphisms by fragment analysis using the GeneMapper technology across a large collection of isolates genotyped by mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit–variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) and IS900 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP-IS900) analyses. Furthermore, we analyzed the structure-function relationships of recombinant HBHA proteins of types C and S by heparin-Sepharose chromatography and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analyses. In silico analysis revealed two forms of HBHA, corresponding to the prototype genomes for the C and S types of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. This observation was confirmed using GeneMapper on 85 M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains, including 67 strains of type C and 18 strains of type S. We found that HBHAs from all type C strains contain a short C-terminal domain, while those of type S present a long C-terminal domain, similar to that produced by Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium. The purification of recombinant HBHA from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis of both types by heparin-Sepharose chromatography highlighted a correlation between their affinities for heparin and the lengths of their C-terminal domains, which was confirmed by SPR analysis. Thus, types C and S of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis may be distinguished by the types of HBHA they produce, which differ in size and adherence properties, thereby providing new evidence that strengthens the genotypic differences between the C and S types of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

Genomic studies have revealed that Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis, the etiologic agent of Johne's disease, or paratuberculosis, has evolved into two distinct lineages related to host specificity. These are referred to as the cattle (C) type and the sheep (S) type (1, 2) and can be consistently distinguished by different genotyping tools available for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (3, 4). In addition to their genomic diversity (5–8), strains belonging to these two lineages exhibit phenotypic differences, including differences in pigmentation, growth rate (9–11), iron metabolic pathways utilized (12), cytokine induction profiles (13), and transcriptional profiles in a human macrophage model (14).

Since the very low growth rate of type S strains is a limiting factor for their characterization, their pathogenicity remains poorly understood. We can assume that the mechanisms of infection for types S and C have common traits, since both can cause paratuberculosis across different ruminant species. Indeed, despite the observed host preferences, bovine paratuberculosis may be due to S strains, and ovine paratuberculosis may be due to C strains (15). By use of a type C strain, it has been established that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis crosses the intestinal barrier through the M cells or epithelial cells present in the dome of Peyer's patches (16–18). During these early events in infection, bacterial adhesins must thus play a crucial role. One of the best-characterized mycobacterial adhesins is the heparin-binding hemagglutinin (HBHA), initially identified in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (19, 20). However, HBHA is also present in many other mycobacteria, both pathogenic and nonpathogenic (21–24).

HBHA is located on the surface of the mycobacterium and has been shown to mediate the binding of the bacillus to epithelial cells and fibroblasts (20). It interacts with sulfated glycoconjugates present on the surfaces of host cells (25). It also plays a role in the dissemination of M. tuberculosis from the lungs to deeper tissues (26). Probably due to its cellular location and its role in extrapulmonary dissemination, HBHA has shown promise as a diagnostic target for the detection of latent tuberculosis in humans (27, 28).

In this study, we identified and characterized the biochemical features of HBHA proteins produced by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains of type C and type S. We provide evidence that these major lineages of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis produce HBHA forms that differ in structure and activity. These findings add new information on the evolution of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and suggest that this adhesin is an adaptation factor for the mycobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and DNA manipulations.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Mycobacterial strains were grown at 37°C in Sauton medium or Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with 0.2% glycerol and albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment medium (ADC; Becton Dickinson, Le Pont-de-Claix, France). M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cultures were supplemented with 2 mg liter−1 mycobactin J (Allied Monitor). Bacteria were harvested at mid-log phase and were kept frozen (−80°C) in aliquots until use. Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) were grown in LB medium supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin or 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin as appropriate. Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and other molecular biology reagents were purchased from New England BioLabs, Roche, or Promega. PCRs were performed using a Techne TC-512 thermal cycler, and the PCR products were sequenced by Genome Express (Takeley, United Kingdom).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain(s)a | Genotype and/or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| M. avium | ||

| M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (n = 85) | ||

| K-10 (ATCC BAA-968) | Bovine isolate, C type | 45 |

| ATCC 19698T | Bovine isolate, C type | 46 |

| 85/14 | Ovine isolate, S type | 2 |

| LN20 | Porcine isolate, S type | 2 |

| Panel of 65 clinical isolates | C type, including various genotypes | 3 |

| Panel of 16 clinical isolates | S type, including various genotypes | 3 |

| M. avium subsp. avium (n = 3) | ||

| ATCC 25291T | Bird isolate | 46 |

| ST18 | Bird isolate | 46 |

| 1999.05332 | Bird isolate | 46 |

| M. avium subsp. silvaticum 6409 (ATCC 49884T) (n = 1) | Wood pigeon isolate | 47 |

| M. avium subsp. hominissuis (n = 55) | ||

| 104 | Human isolate | 46 |

| Panel of 54 clinical isolates | Various genotypes | 34 |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | Human isolate | 48 |

| M. bovis BCG | Vaccine strain | WHO |

| M. smegmatis mc2155 (ATCC 00084) | Lab strain | |

| E. coli strains | ||

| TOP10 | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Invitrogen |

A superscript “T” indicates a type strain.

Table 2.

Plasmids

| Plasmid(s) | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Original plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | lacZα gene, T7 and Sp6 promoters; Ampr Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pET vectors | T7 promoter, His tag coding sequence, lacI gene; Kanr [pET-24d(+) and pET-24a(+)] or Ampr [pET-22b(+)] | Novagen |

| Resulting plasmids | ||

| pET::mapS-HBHA | pET-22b(+)::hbhA M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (Ampr) | This study |

| pET::mapS-HBHAΔCter | pET-24a(+)::hbhA M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S with C-terminal deletion (aa 1–157) and N-terminal His tag (Kanr) | This study |

| pET::mapLN20-HBHA | pET-22b(+)::hbhA M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis LN20 (Ampr) | This study |

| pET::BCG HBHA | pET-24d(+)::hbhA M. bovis BCG (Kanr) | This study |

| pET::Sm-HBHA | pET-24d(+)::hbhA M. smegmatis mc2155 (Kanr) | 21 |

| pET::maa-HBHA | pET-24d(+)::hbhA M. avium subsp. avium 25291 (Kanr) | This study |

| pET::mapC-HBHA | pET-24d(+)::hbhA M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C 19698 (Kanr) | This study |

Antibiotic resistance is shown in parentheses (Kan, kanamycin; Tet, tetracycline; Amp, ampicillin; Str, streptomycin).

Fluorescent DNA fragment analysis.

The hbhA gene polymorphism was investigated using a comprehensive collection of strains of the species Mycobacterium avium. The sizes of the PCR products corresponding to the region of the hbhA gene coding for the C-terminal domain of the protein were determined after the amplification of genomic DNA from 67 M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C strains, 18 M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strains, including strain LN20, 55 Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis strains, and 3 Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium strains selected according to their genotypes (data not shown). The regions of the hbhA genes coding for the C-terminal domains of the proteins were amplified with primer P7, labeled at its 5′ end with a 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) fluorophore, and primer P8 (Table 3) according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Applied Biosystems, USA). The fragments were amplified after a denaturation cycle of 5 min at 94°C by using only 23 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final elongation cycle at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were mixed with Hi-Di formamide and GeneScan 600 LIZ size standard (Applied Biosystems, USA). The results were visualized using ABI GeneMapper software, version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Table 3.

List of primers used in this studya

| Name | Targetb | Sequencec | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | mapS HBHA-F | ATATACATATGGCGGAAAACCCG | NdeI |

| P2 | mapS HBHA-R | ATATAAAGCTTTCACTTCTGGGTGACC | HindIII |

| P3 | HBHA-F | TATACATATGACCATGGCGGAAAACCCGAACATCG | NdeI |

| P4 | HBHA-R | ATATAAGCTTGGTACCCACGAGGTGGTTCACGCC | HindIII |

| P5 | HBHA ΔCT-F | ATATCATATGCACCACCACCACCACCACATGGCGGAAAACCCG | NdeI |

| P6 | HBHA ΔCT-R | ATATAAGCTTCTAGATGCCCACCAGCTTGGC | HindIII |

| P7 | 5′ FAM-HBHA CT-F | TCGCTCGCAGACCCGCGCGGTCGG | |

| P8 | HBHA CT-R | CTACCTACTTCTGGGTGACCTTCTTGGC | |

| P9 | HBHA CT-F | TATAGAATTCCGCCAAGCTGGTGGGCATCGAGCTGCCG | EcoRI |

Primers were designed on the basis of conserved hbhA sequences of Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium, Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (types S and C), Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Mycobacterium bovis BCG.

F, forward; R, reverse; ΔCT, deletion of the C-terminal domain; FAM, the fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein.

Underlining indicates restriction sites.

Plasmid constructions, sequencing, and production of recombinant HBHA (rHBHA) in E. coli.

The hbhA genes were amplified by PCR with synthetic oligonucleotides P1, P2, P3, and P4 (Sigma) (Table 3) from chromosomal DNA by using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). Chromosomal DNA was prepared from cultures of M. avium subsp. avium strain 25291, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C strains K-10 and ATCC 19698, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strains 19I, 269OV, M71/03, 21I, 85-14, and LN20, M. bovis BCG, and Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 (Table 1; also data not shown).

The fragments were amplified after a short denaturation cycle of 3 min at 95°C by using 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final elongation cycle at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products containing the HBHA-coding sequences, including the stop codons, were digested by NdeI and HindIII and were then inserted into pET-24a(+) (Novagen). These plasmids, listed in Table 2, were used to transform E. coli TOP10 for sequencing and E. coli BL21(DE3) for recombinant protein production. After transformation, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were grown at 37°C in 250 ml LB broth supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin. At an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and growth was continued for 4 h. The cultures were then centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The cells were washed twice in 20 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2)–0.05% Tween 80 and were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended with 15 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2)–0.05% Tween 80 and were sonicated twice for 5 min at 4°C using a Branson sonifier, model S-250D. The bacterial lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, filtered (pore size, 0.45 μm), and subjected to heparin-Sepharose chromatography as described below.

The gene coding for a truncated HBHA molecule, called mapS-HBHAΔCter, was generated by PCR using chromosomal DNA of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain 19I and oligonucleotides P5 and P6 (described in Table 3), designed to produce a hybrid protein carrying a His tag and lacking amino acids 158 to 205. The PCR product was digested by NdeI and HindIII and was then inserted into the pET expression vector (Novagen), generating pET::mapS-HBHAΔCter. This plasmid was used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) for recombinant protein production. The recombinant mapS-HBHAΔCter was purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose chromatography (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Purification of recombinant HBHA by heparin-Sepharose chromatography.

Recombinant HBHA produced in E. coli without a His tag was purified by heparin-Sepharose chromatography as described previously (24) using recombinant E. coli lysates prepared as described above. All chromatographic steps were carried out on the BioLogic chromatography system (Bio-Rad) at room temperature, and the absorbance at 280 nm was continuously monitored during purification using a HiTrap Heparin HP column (1 ml; 0.7 by 2.5 cm; GE Healthcare) prepacked with heparin-Sepharose. The column was washed with 100 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) until the absorbance at 280 nm was close to zero. The bound material was eluted by a 0 to 1 M NaCl linear gradient in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), using a flow rate of 0.6 ml min−1, and was automatically collected in 1-ml fractions. Whole-cell lysates, flowthrough material, and eluted fractions were analyzed by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) performed according to the method of Laemmli (29).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Mycobacterial whole-cell lysates and purified recombinant HBHA were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 12% running gels and 4% stacking gels. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman, Germany), and the membranes were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.05% Tween and were washed three times in PBS–0.05% Tween–1% BSA before incubation with the anti-HBHA monoclonal antibody 3921E4 (19, 30). After three washing steps with PBS–0.05% Tween, membranes were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) at a 1:2,000 dilution. The substrates nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate were used to develop the immunoblots.

Protein analysis.

Multiple amino acid alignments were performed with ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/).

Biotinylation of heparin.

Biotinylated heparin was prepared by following the procedure described by Osmond et al. (31). Briefly, 10 mg of low-molecular-weight heparin (Enoxaparin) was reductively aminated at 70°C under constant stirring, once with 200 mg of NaCNBH3 and then once with 100 mg of NaCNBH3 (Sigma), for 48 h for each step. The aminated heparin was then dialyzed against 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 7.4) and was coupled to 0.75 mg of sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-LC-biotin (Uptima) overnight at 4°C under constant stirring. Biotinylated heparin was dialyzed against H2O and was lyophilized for storage until use.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis.

The BIAcore T100 system (GE Healthcare) was used for analysis of the molecular interactions between recombinant HBHA, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C HBHA (mapC-HBHA), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S HBHA (mapS-HBHA), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis L20 HBHA (mapLN20-HBHA), M. avium subsp. avium HBHA (maa-HBHA), BCG HBHA, M. smegmatis HBHA (ms-HBHA), or mapS-HBHAΔCter and heparin. Recombinant streptavidin (Pierce) was covalently bound on two flow cells (Fc) of a CM4 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) with HBS (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20 [pH 7.4]) as the running buffer. Standard amine coupling was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, generating an immobilization signal of 1,000 resonance units (RU). After three 60-s injections of 1 M NaCl–50 mM NaOH, 5 μg ml−1 of biotinylated heparin was injected at a flow rate of 2 μl min−1 for 90 s onto a streptavidin-coated Fc to obtain 30 RU. The other streptavidin-coated Fc was not modified and was used as a control surface. Binding was performed at 25°C, with 50 mM Tris-HCl–50 mM NaCl–0.05% Tween 20 (pH 7.2) as the running buffer. The protein solutions were injected over the two flow cells for 180 s at 30 μl min−1 at concentrations ranging from 1.2 to 300 or 900 nM. Dissociation was measured over 180 s. The surfaces were regenerated with a 1 M NaCl solution for 60 s, followed by a 100-IU/ml heparin solution for 60 s and a 120-s buffer wash. The signals obtained on the control surface and with the buffer injection were subtracted from the signal responses with the test samples. Constant affinities were calculated at equilibrium by the steady-state method and with BIAevaluation software, version 2.03.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed on 96-well Maxisorp microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) coated with 50 μl of a purified protein derivative from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (Johnin PPD [PPDj]) (National Veterinary Institute, Oslo, Norway) at 25 mg liter−1 in PBS or with recombinant BCG HBHA, mapS-HBHA, mapC-HBHA, or mapS-HBHAΔCter at 0.1 mg ml−1 in PBS at 4°C overnight. Plates were then washed three times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS/T) and were blocked for 1 h at 37°C with PBS/T containing 0.5% (wt/vol) gelatin (PBS/T/G). The sera tested have been described previously (32) and include a positive control from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis-infected cattle, a negative control, and a set of sera obtained from ruminants naturally infected by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis of type C or type S. Each serum sample was diluted at 1:100 in 50 μl PBS/T/G, and plates were incubated for 2.5 h at 37°C. Plates were then washed five times with PBS/T and were incubated for 90 min at 37°C with 50 μl peroxidase-conjugated anti-ruminant IgG (Chekit; Bommeli AG, Bern, Switzerland), diluted at 1:600 in PBS/T/G. Plates were washed five times with PBS/T, and 50 μl peroxidase substrate was added. After a 15-min incubation at 37°C, the plates were read photometrically at 414 nm. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of hbhA have been deposited in the GenBank databases under the following accession numbers: for M. tuberculosis, AF074390; for M. bovis BCG, 4696475; for M. smegmatis, DQ059383; for M. avium subsp. avium, JN129485; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C strain ATCC 19698, JX536267; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C strain K-10, JX536266; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain 19I, KC920678; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain 269OV, KC920679; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain M71/03, KC920680; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain 21I, KC920681; for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain 85/14, KC920682; and for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strain LN20, KC920683.

RESULTS

Variability of the C-terminal domain of HBHA.

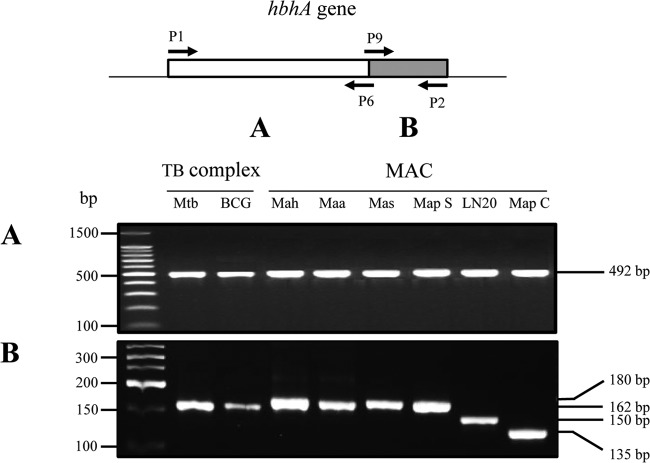

Comparative genomic data show that hbhA is highly conserved among mycobacterial species. Alignment of HBHA protein sequences reveals that the large N-terminal domains are highly conserved, while the C-terminal domains are heterogeneous between mycobacterial species (24, 33). To identify the hbhA genes in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strains, separate PCR analyses were performed on the 5′ and 3′ portions of the gene. The results indicate that the hbhA gene is present in S strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and that the sizes of the 5′ ends, coding for the N-terminal moieties of HBHA, are invariable among the samples analyzed (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the sizes of the PCR products targeting the 3′ end of the gene, coding for the C-terminal domain of HBHA, were variable; PCR products from type S strains were longer than those from type C strains. The hbhA gene amplified from type S strains was the same size as the M. avium subsp. avium and M. avium subsp. hominissuis hbhA genes. The shorter hbhA gene was observed only with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C strains. Isolate LN20, a strain intermediate between the S and C lineages according to deletion analysis (1), had an hbhA gene of a size intermediate between those for types C and S (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Interspecies and intraspecies variability of the hbhA gene. Shown are PCR amplification products of the DNA coding for the N-terminal domain (A) and the C-terminal domain (B) of HBHA, obtained by using genomic DNA of M. tuberculosis (Mtb), BCG, M. avium subsp. hominissuis (Mah) (1 sample representative of 28 strains analyzed), M. avium subsp. avium (Maa), M. avium subsp. silvaticum (Mas), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (Map S) (1 sample representative of 17 strains analyzed), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain LN20, and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C (Map C) (1 sample representative of 34 strains analyzed). The arrows in the diagram at the top indicate the positions and directions of primers P1, P2, P6, and P9, the sequences of which were deduced from the HBHA-encoding gene of M. tuberculosis. Positions on a 100-bp ladder (Promega) (A) and a low-molecular-weight DNA ladder (New England BioLabs) (B), used as molecular weight markers, are indicated on the left. The sizes of the PCR products are indicated on the right.

Specificity of the hbhA gene according to the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis lineage.

To extend the analysis of hbhA variability across M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis lineages, we performed fluorescent PCR fragment analyses on the 3′ portions of the genes from a representative panel of isolates, selected from a comprehensive collection of strains at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA). This panel (Table 1; also data not shown) consists of strains isolated from various animals (cattle, sheep, goats, red deer, rabbits) and humans of various geographical origins (data not shown). Furthermore, the isolates were selected based on distinct mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit–variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) and IS900 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiles as described previously (3). This panel was completed by 3 strains of M. avium subsp. avium isolated from birds and 55 human isolates of M. avium subsp. hominissuis described previously (34).

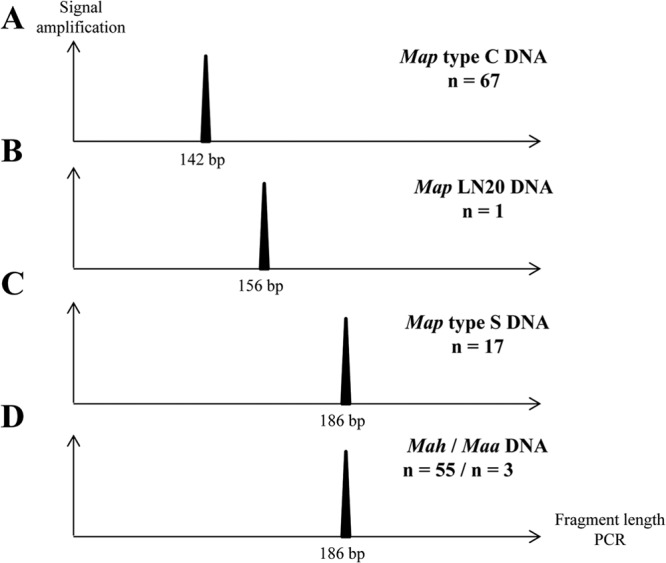

All strains of M. avium subsp. avium and M. avium subsp. hominissuis gave PCR products of 186 bp. All strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (except for LN20) yielded products of the same size, 186 bp (Fig. 2C and D). M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis LN20 was the only strain to yield a PCR product of 156 bp (Fig. 2B). For all 67 M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains of type C, fragments of 142 bp were amplified (Fig. 2A). These results confirm that within the subspecies M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, lineages S and C can be distinguished by the sizes of their hbhA genes.

Fig 2.

Distinct hbhA genes within the subspecies M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were examined with a large collection of isolates. The gene coding for the C-terminal domain of HBHA was amplified by PCR on genomic DNA using primers labeled at their 5′ ends with the fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein. Results were visualized using ABI GeneMapper software, version 4.0, with 600 LIZ size standards (Applied Biosystems, USA). The expected sizes of the PCR products are 142 bp with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C genomic DNA (A), 156 bp with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis LN20 genomic DNA (B), and 186 bp with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (C), M. avium subsp. avium, or M. avium subsp. hominissuis (D) genomic DNA. This analysis was performed on 67 strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C, 18 strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S, including strain LN20, 55 M. avium subsp. hominissuis strains, and 3 strains of M. avium subsp. avium. n, number of strains analyzed.

Size of native HBHA in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis.

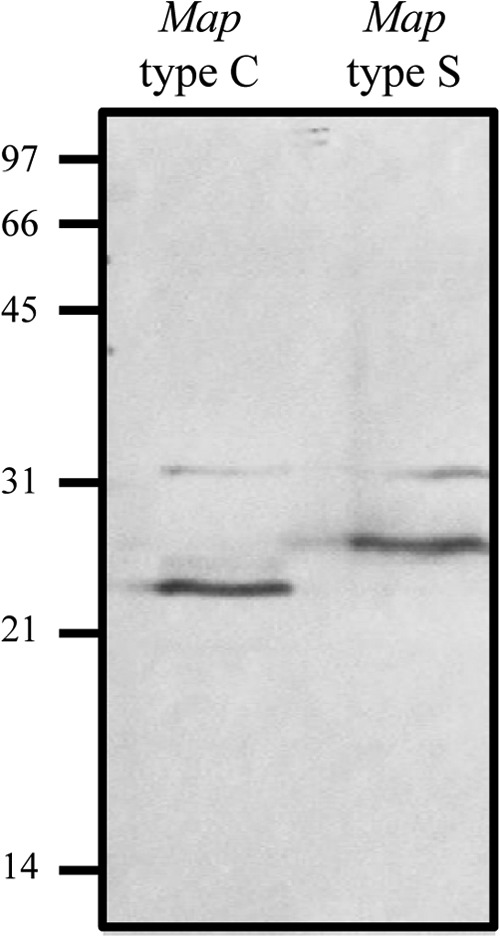

To determine whether the longer hbhA genes of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strains result in HBHA proteins longer than those of type C strains, immunoblot analyses were performed on the different strains. Whole-cell lysates of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C (strain K-10) and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (strain 85/14) were analyzed using monoclonal antibody 3921E4 (35). These analyses showed the different forms of HBHA produced in each lineage of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, with apparent molecular masses of 22 kDa for HBHA from type C and 28 kDa for HBHA from type S (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Immunoblot analysis of native HBHAs produced by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis types C and S. Whole-cell lysates of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C (left lane) and type S (right lane) strains were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated with the anti-HBHA monoclonal antibody 3921E4. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

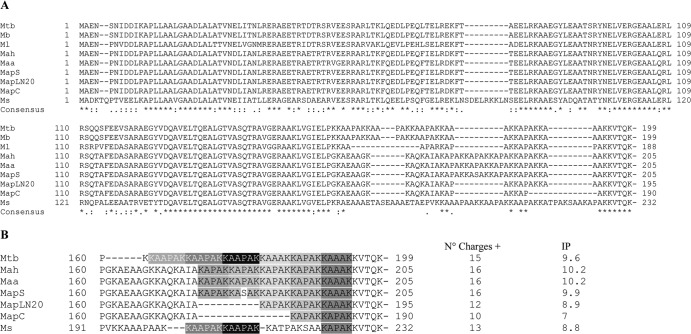

Sequence features of the HBHA homologues.

To determine the basis for the genetic variability of HBHAs from the different lineages, the hbhA gene of each lineage was sequenced, and deduced amino acid sequences were aligned with those of sequences already known for the M. tuberculosis complex and M. smegmatis (Fig. 4). The sequence data confirmed the findings from the PCR and immunoblot analyses. The HBHA of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (mapS-HBHA) consists of 205 amino acids, whereas that of type C (mapC-HBHA) has 190 amino acids. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain LN20 produces a 195-amino-acid HBHA molecule (mapLN20-HBHA). The sequence similarities among these HBHA proteins are high (89% similarity), as expected, up to residue 162, after which the sequences are more divergent. The divergences observed in the C-terminal regions of HBHA correspond mainly to deletions or differences in the lysine-rich repeats. In Fig. 4B, the sequences are presented as a succession of the repeats defined by Lebrun et al. (25). Interestingly, the divergences of HBHA correspond to different numbers of these repeats (Fig. 4B). Pethe et al. (36) and, recently, Lebrun et al. (25) have shown a direct correlation between the number of lysine-rich repeats (R2) and the strength of heparin binding of HBHA. Since the HBHA produced by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S contains 5 repeats, we hypothesized that its heparin-binding activity may be similar to that of HBHA produced by M. avium subsp. avium but greater than that for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C, which contains only 2 repeats.

Fig 4.

Alignment of HBHA sequences from different mycobacterial species. (A) The amino acid sequences of M. tuberculosis HBHA were aligned with those of its homologues from other mycobacterial species by using the ClustalW program with the BLOSUM64 matrix allowing gaps. Asterisks represent identical residues; colons, conserved substitutions; periods, semiconserved substitutions. (B) Multiple alignment of the C-terminal heparin-binding domain of HBHA. The lysine-rich hexa-repeats (R1) (white letters on a gray ground) and penta-repeats (R2) (black letters on a gray ground) defined by Lebrun et al. (25) are indicated. The numbers of charges distributed throughout the C-terminal domains of different HBHA homologues (amino acids 158 to 232) and their isoelectric points (IP) are given to the right of the sequences. Mb, M. bovis; Ml, M. leprae; Ms, M. smegmatis; C, consensus.

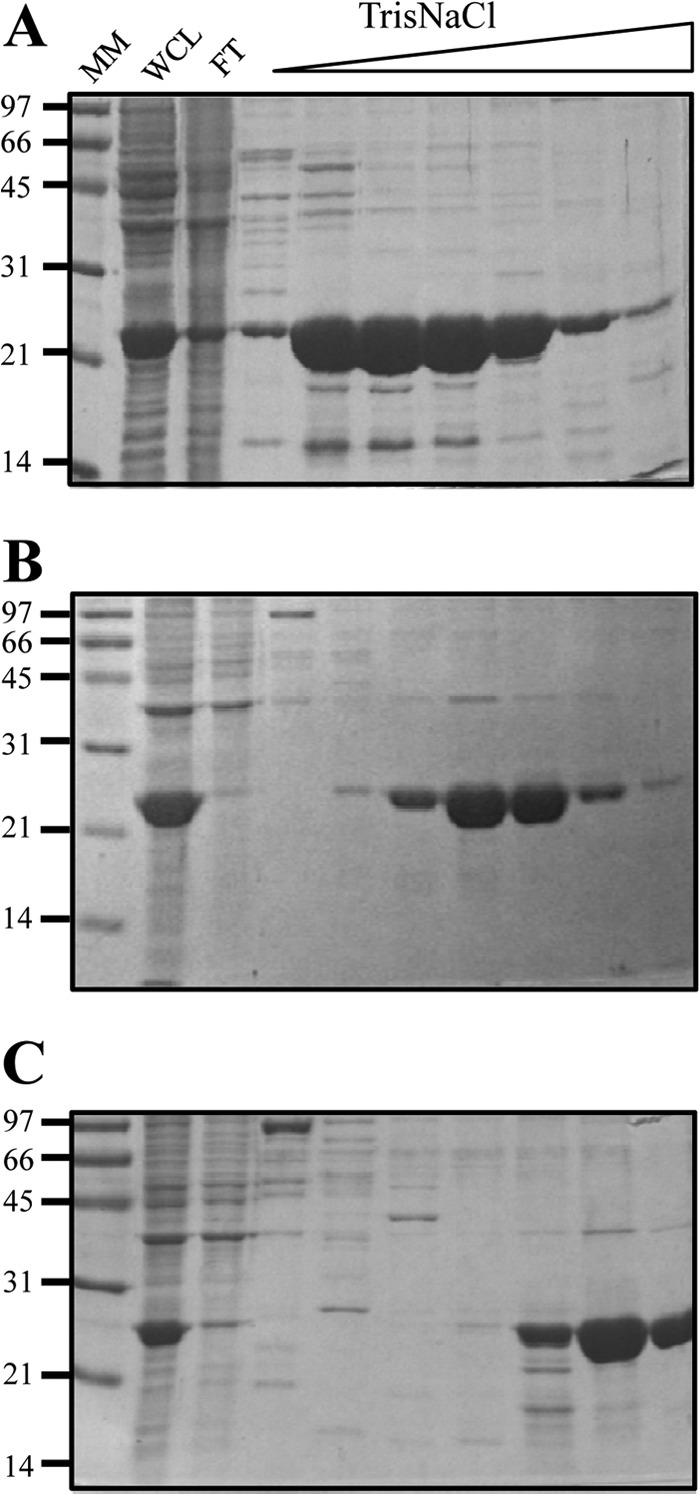

Capacity of map-HBHA to bind to heparin-Sepharose.

Recombinant HBHA proteins produced in E. coli were analyzed by heparin-Sepharose chromatography. As described previously (24), mapC-HBHA bound weakly to heparin-Sepharose and was eluted at 200 mM NaCl in a NaCl gradient from 0 to 1 M (Fig. 5A). The presence of a third R2 motif in mapLN20-HBHA strengthened the interaction with heparin, as demonstrated by delayed elution at 410 mM NaCl (Fig. 5B). The highest affinity was observed for mapS-HBHA, which contains 5 R2 repeats. This HBHA variant was eluted only when the NaCl concentration was increased to 600 mM (Fig. 5C). Together, these results indicate that a genetic difference between the lineages of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis translates into different lengths of the HBHA protein and into differences in binding activity with sulfated glycoconjugates.

Fig 5.

Differences between rHBHA proteins from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C, LN20, and type S in the strength of binding to heparin-Sepharose. Lysates of E. coli expressing recombinant HBHA of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C (A), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis LN20 (B), and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S (C) were sonicated. The soluble material was subjected to heparin-Sepharose chromatography and was eluted using a 0 to 1 M NaCl gradient. SDS-PAGE analyses were performed on whole-cell lysates (WCL), flowthrough (FT), and elution fractions of rHBHA. The positions of molecular mass markers (MM), expressed in kilodaltons, are indicated on the left.

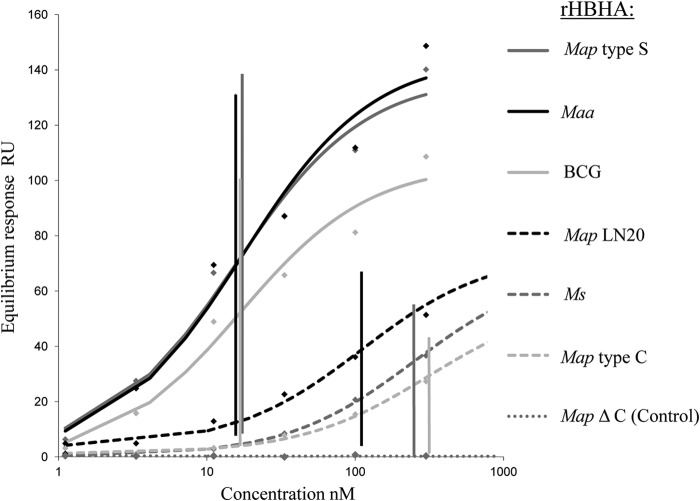

SPR analysis of the HBHA-heparin interactions.

To quantify the specific interactions between the different recombinant HBHA forms and heparin, we employed the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) method. In addition to mapC-HBHA, mapS-HBHA, and mapLN20-HBHA, produced in E. coli and purified by heparin-Sepharose chromatography, HBHA proteins from M. smegmatis (ms-HBHA), M. avium subsp. avium (maa-HBHA), and M. bovis BCG (BCG HBHA) were used as controls for low and high affinity for heparin, as described previously (21, 25, 36). Additionally, recombinant mapS-HBHAΔCter, lacking the C-terminal domain, was used as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 6, and as expected, recombinant mapS-HBHAΔCter did not interact with the heparin sensor chip, demonstrating that the N-terminal domain of HBHA is not involved in heparin binding. In contrast, the other HBHA molecules bound to the sensor chip with various affinities. These proteins could be classified into two groups: (i) HBHA proteins with low heparin-binding affinity, including ms-HBHA, mapC-HBHA, and mapLN20-HBHA, with KD (equilibrium dissociation constants) around 249, 314, and 110 nM, respectively, and (ii) HBHA proteins with high heparin-binding affinity, comprising BCG HBHA, maa-HBHA, and mapS-HBHA, for which the KD were close to 20 nM. These results concurred with the qualitative results obtained by affinity chromatography and strengthen the relationship between the length of the C-terminal domain and the binding function of HBHA with sulfated glycoconjugates.

Fig 6.

Quantification by SPR analysis of the heparin-binding activities of the rHBHA proteins of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C, LN20, and type S. SPR analysis of the binding of recombinant HBHA to heparin was performed on a BIAcore T100 system (GE Healthcare). Biotinylated heparin was immobilized on a streptavidin-coated CM4 sensor chip. Recombinant HBHA proteins purified by heparin-Sepharose chromatography were injected over a range of concentrations at a flow rate of 30 μl min−1. Recombinant mapS-HBHAΔCter was used as a negative control. KD were determined by the equilibrium method. The KD results (nM) are indicated at the intersections of the vertical lines with the concentration axis.

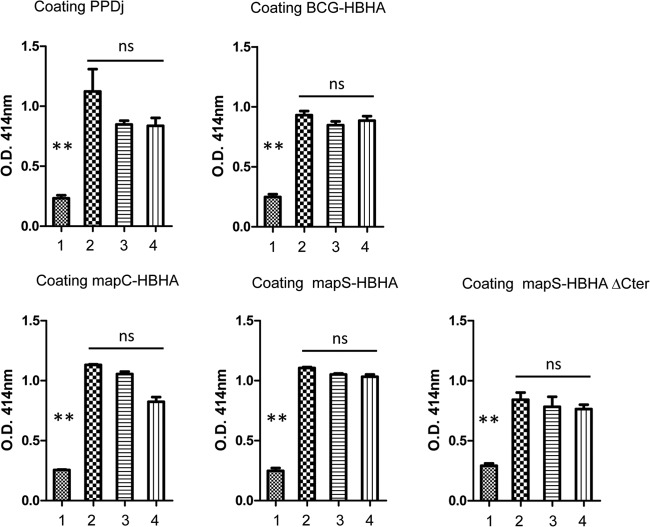

Sera from animals with Johne's disease react with HBHA produced by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis.

To investigate whether the antigenic properties of HBHA differed according to the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis lineage, we performed ELISA based on mapC-HBHA versus mapS-HBHA by using sera from animals with clinical infections by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C or type S strains. As shown in Fig. 7, the sera from animals infected with a type C or a type S strain reacted similarly with both forms of HBHA. In addition, all the serum samples in this panel responded similarly to BCG HBHA and mapS-HBHAΔCter, as well as to PPDj. These results indicate that the differences in HBHA sequences did not affect the antigenic properties of HBHA and that this B-cell response is not specific with respect to mycobacterial species and subspecies.

Fig 7.

Reactivity of a serum panel with the rHBHA proteins from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains of types C and S. ELISA were performed with plates coated with either PPDj, recombinant BCG HBHA, mapS-HBHA, mapS-HBHAΔCter, or mapC-HBHA. The panel of sera tested included a M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis-negative commercial antiserum (lane 1), a M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis-positive commercial serum (lane 2), and sera obtained from ruminants infected by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C (lane 3) or type S (lane 4). Each serum sample was diluted at 1:100 in 50 μl PBS/T/G and was incubated for 2.5 h at 37°C. The plates were then washed and were incubated for 90 min at 37°C with 50 μl peroxidase-conjugated anti-ruminant IgG diluted at 1:600 in PBS/T/G. After washing, the plates were developed with 50 μl of a peroxidase substrate for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl 1 N HCl, and the plates were read photometrically at 490 nm. The results shown are averages for triplicate samples from one experiment representative of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with Tukey's multiple comparison tests. **, P < 0.001; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

During the early stages of infection, pathogenic microorganisms interact with cell surface receptors of eukaryotic target cells that are normally required for their physiological processes, such as signal transduction, cell-cell interactions, and cell-matrix interactions. In mycobacteria, two major adhesins, named HBHA and laminin binding protein (LBP), have been reported (20, 21, 37–39) to mediate these interactions with sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) molecules, such as heparan sulfate (HS-GAG), present on the surfaces of various types of eukaryotic cells (40). This study focused on the HBHA expressed in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, and we identified HBHA expressed by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S strains and compared its biochemical properties to those for type C strains.

Surprisingly, in silico analysis showed that the C-terminal part of HBHA identified in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis diverged according to the lineage (type C versus type S). Until now, the HBHA molecules reported for the subspecies M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis belonged to type C (23, 24). The variability between mapC-HBHA and mapS-HBHA is restricted to the C-terminal domain of the protein. However, this difference in structure may be important for the function of these adhesins, because this domain is responsible for the binding of HBHA to HS-GAG (25, 36). These observations add new evidence to the distinctness of type S versus type C strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and are consistent with the previously described biphasic scenario for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis evolution (2).

One of the major outcomes of this study is the discovery that, in contrast to mapC-HBHA, mapS-HBHA was 98.6% similar to the HBHA proteins expressed by M. avium subsp. avium and M. avium subsp. hominissuis. These results suggest that for this locus, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type S more closely resembles other subspecies of M. avium than M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type C, as has also been observed for some other markers used to study Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) evolution (2, 41). Furthermore, while typing methods such as gyrA and gyrB single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typing have suggested that type S strains can be subdivided into subtypes called I and III (3), this study showed no difference between the hbhA genes of subtype I and III strains. Additionally, a single strain of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (LN20), originally isolated from a pig in Quebec, Canada, presented an HBHA molecule of intermediate size. Interestingly, this observation correlates with the analysis of Alexander et al. (1) showing certain intermediate features of strain LN20.

This study also revealed that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis HBHA molecules also differ in biochemical properties according to lineage (S versus C). Further studies should be undertaken to decipher the consequences of these two forms of HBHA expressed in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in terms of attachment to epithelial cells (21) and host and/or organ specificity (42). Indeed, the particularity of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis is to have a tropism for the intestine and, within the subspecies M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, a preferred host range, such as sheep for S strains and cattle for C strains. Since HS-GAG structures differ according to both hosts and organs (42), it is possible that mycobacterial pathogens use heparin-binding domain variability to define their host preference or anatomic tropism.

Despite the structural and biochemical differences between mapC-HBHA and mapS-HBHA, B-cell responses to the two different forms were identical. However, T-cell responses to these different HBHA forms were not investigated. It has been shown that in humans, the native HBHA purified from BCG can be used to detect individuals latently infected by M. tuberculosis (27, 43), and that important effector functions of the HBHA-specific T cells require the protein to be methylated. Furthermore, protective immunogenicity induced by HBHA has been shown to depend also on a precise methylation pattern (28, 44). Investigation of the T-cell responses in animals infected by strains of each type thus requires establishment of the exact methylation patterns of the HBHA produced by each lineage and the availability of mapC-HBHA and mapS-HBHA in their correctly methylated forms. We have observed recently that lysine residues 168 and 153 of native mapC-HBHA are methylated (24), but the precise methylation patterns and other translational modifications remain to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F.B., L.H.L., C.C.B., and T.C. were supported by the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) and by the EMIDA Mycobactdiagnosis project. K.S. was funded by the Scottish Government Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander DC, Turenne CY, Behr MA. 2009. Insertion and deletion events that define the pathogen Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 191:1018–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turenne CY, Collins DM, Alexander DC, Behr MA. 2008. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. avium subsp. avium are independently evolved pathogenic clones of a much broader group of M. avium organisms. J. Bacteriol. 190:2479–2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biet F, Sevilla IA, Cochard T, Lefrancois LH, Garrido JM, Heron I, Juste RA, McLuckie J, Thibault VC, Supply P, Collins DM, Behr MA, Stevenson K. 2012. Inter- and intra-subtype genotypic differences that differentiate Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis strains. BMC Microbiol. 12:264. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellanos E, Romero B, Rodriguez S, de Juan L, Bezos J, Mateos A, Dominguez L, Aranaz A. 2010. Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis types II and III isolates by a combination of MIRU-VNTR loci. Vet. Microbiol. 144:118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellanos E, Aranaz A, Gould KA, Linedale R, Stevenson K, Alvarez J, Dominguez L, de Juan L, Hinds J, Bull TJ. 2009. Discovery of stable and variable differences in the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis type I, II, and III genomes by pan-genome microarray analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:676–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohmann K, Strommenger B, Stevenson K, de Juan L, Stratmann J, Kapur V, Bull TJ, Gerlach GF. 2003. Characterization of genetic differences between Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis type I and type II isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5215–5223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh IB, Bannantine JP, Paustian ML, Tizard ML, Kapur V, Whittington RJ. 2006. Genomic comparison of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis sheep and cattle strains by microarray hybridization. J. Bacteriol. 188:2290–2293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh IB, Whittington RJ. 2005. Deletion of an mmpL gene and multiple associated genes from the genome of the S strain of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis identified by representational difference analysis and in silico analysis. Mol. Cell. Probes 19:371–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins DM, Gabric DM, de Lisle GW. 1990. Identification of two groups of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis strains by restriction endonuclease analysis and DNA hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1591–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Lisle GW, Collins DM, Huchzermeyer HF. 1992. Characterization of ovine strains of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis by restriction endonuclease analysis and DNA hybridization. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 59:163–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittington RJ, Marsh IB, Saunders V, Grant IR, Juste R, Sevilla IA, Manning EJ, Whitlock RH. 2011. Culture phenotypes of genomically and geographically diverse Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates from different hosts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1822–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janagama HK, Kumar S, Bannantine JP, Kugadas A, Jagtap P, Higgins L, Witthuhn B, Sreevatsan S. 2010. Iron-sparing response of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis is strain dependent. BMC Microbiol. 10:268. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janagama HK, Jeong K, Kapur V, Coussens P, Sreevatsan S. 2006. Cytokine responses of bovine macrophages to diverse clinical Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis strains. BMC Microbiol. 6:10. 10.1186/1471-2180-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motiwala AS, Janagama HK, Paustian ML, Zhu X, Bannantine JP, Kapur V, Sreevatsan S. 2006. Comparative transcriptional analysis of human macrophages exposed to animal and human isolates of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis with diverse genotypes. Infect. Immun. 74:6046–6056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittington RJ, Taragel CA, Ottaway S, Marsh I, Seaman J, Fridriksdottir V. 2001. Molecular epidemiological confirmation and circumstances of occurrence of sheep (S) strains of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in cases of paratuberculosis in cattle in Australia and sheep and cattle in Iceland. Vet. Microbiol. 79:311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bermudez LE, Petrofsky M, Sommer S, Barletta RG. 2010. Peyer's patch-deficient mice demonstrate that Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis translocates across the mucosal barrier via both M cells and enterocytes but has inefficient dissemination. Infect. Immun. 78:3570–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momotani E, Whipple DL, Thiermann AB, Cheville NF. 1988. Role of M cells and macrophages in the entrance of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis into domes of ileal Peyer's patches in calves. Vet. Pathol. 25:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigurdardóttir OG, Bakke-McKellep AM, Djonne B, Evensen O. 2005. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis enters the small intestinal mucosa of goat kids in areas with and without Peyer's patches as demonstrated with the everted sleeve method. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menozzi FD, Bischoff R, Fort E, Brennan MJ, Locht C. 1998. Molecular characterization of the mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin, a mycobacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:12625–12630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menozzi FD, Rouse JH, Alavi M, Laude-Sharp M, Muller J, Bischoff R, Brennan MJ, Locht C. 1996. Identification of a heparin-binding hemagglutinin present in mycobacteria. J. Exp. Med. 184:993–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biet F, Angela de Melo Marques M, Grayon M, Xavier da Silveira EK, Brennan PJ, Drobecq H, Raze D, Vidal Pessolani MC, Locht C, Menozzi FD. 2007. Mycobacterium smegmatis produces an HBHA homologue which is not involved in epithelial adherence. Microbes Infect. 9:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy VM, Kumar B. 2000. Interaction of Mycobacterium avium complex with human respiratory epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1189–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sechi LA, Ahmed N, Felis GE, Dupre I, Cannas S, Fadda G, Bua A, Zanetti S. 2006. Immunogenicity and cytoadherence of recombinant heparin binding haemagglutinin (HBHA) of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis: functional promiscuity or a role in virulence? Vaccine 24:236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefrancois LH, Bodier CC, Lecher S, Gilbert FB, Cochard T, Harichaux G, Labas V, Teixeira-Gomes AP, Raze D, Locht C, Biet F. 2013. Purification of native HBHA from Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. BMC Res. Notes 6:55. 10.1186/1756-0500-6-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebrun P, Raze D, Fritzinger B, Wieruszeski JM, Biet F, Dose A, Carpentier M, Schwarzer D, Allain F, Lippens G, Locht C. 2012. Differential contribution of the repeats to heparin binding of HBHA, a major adhesin of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 7:e32421. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pethe K, Alonso S, Biet F, Delogu G, Brennan MJ, Locht C, Menozzi FD. 2001. The heparin-binding haemagglutinin of M. tuberculosis is required for extrapulmonary dissemination. Nature 412:190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masungi C, Temmerman S, Van Vooren JP, Drowart A, Pethe K, Menozzi FD, Locht C, Mascart F. 2002. Differential T and B cell responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin in infected healthy individuals and patients with tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 185:513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Temmerman S, Pethe K, Parra M, Alonso S, Rouanet C, Pickett T, Drowart A, Debrie AS, Delogu G, Menozzi FD, Sergheraert C, Brennan MJ, Mascart F, Locht C. 2004. Methylation-dependent T cell immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin. Nat. Med. 10:935–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rouse DA, Morris SL, Karpas AB, Probst PG, Chaparas SD. 1990. Production, characterization, and species specificity of monoclonal antibodies to Mycobacterium avium complex protein antigens. Infect. Immun. 58:1445–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osmond RI, Kett WC, Skett SE, Coombe DR. 2002. Protein-heparin interactions measured by BIAcore 2000 are affected by the method of heparin immobilization. Anal. Biochem. 310:199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biet F, Bay S, Thibault VC, Euphrasie D, Grayon M, Ganneau C, Lanotte P, Daffe M, Gokhale R, Etienne G, Reyrat JM. 2008. Lipopentapeptide induces a strong host humoral response and distinguishes Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis from M. avium subsp. avium. Vaccine 26:257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locht C, Raze D, Rouanet C, Genisset C, Segers J, Mascart F. 2008. The mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin: a virulence factor and antigen useful for diagnostics and vaccine development, p 305–322 In Daffé M, Reyrat JM. (ed), The mycobacterial cell envelope. ASM Press; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thibault VC, Grayon M, Boschiroli ML, Hubbans C, Overduin P, Stevenson K, Gutierrez MC, Supply P, Biet F. 2007. New variable number tandem repeat markers for typing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. avium strains: comparison with IS900 RFLP and IS1245 RFLP typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2404–2410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouse DA, Morris SL, Karpas AB, Mackall JC, Probst PG, Chaparas SD. 1991. Immunological characterization of recombinant antigens isolated from a Mycobacterium avium lambda gt11 expression library by using monoclonal antibody probes. Infect. Immun. 59:2595–2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pethe K, Aumercier M, Fort E, Gatot C, Locht C, Menozzi FD. 2000. Characterization of the heparin-binding site of the mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14273–14280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki K, Matsumoto S, Hirayama Y, Wada T, Ozeki Y, Niki M, Domenech P, Umemori K, Yamamoto S, Mineda A, Matsumoto M, Kobayashi K. 2004. Extracellular mycobacterial DNA-binding protein 1 participates in mycobacterium-lung epithelial cell interaction through hyaluronic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 279:39798–39806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Melo Marques MA, Mahapatra S, Nandan D, Dick T, Sarno EN, Brennan PJ, Vidal Pessolani MC. 2000. Bacterial and host-derived cationic proteins bind α2-laminins and enhance Mycobacterium leprae attachment to human Schwann cells. Microbes Infect. 2:1407–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefrançois LH, Pujol C, Bodier CC, Teixeira-Gomez AP, Drobecq H, Rosso ML, Raze D, Dias AA, Hugot JP, Chacon O, Barletta RG, Locht C, Vidal Pessolani MC, Biet F. 2011. Characterization of the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis laminin-binding/histone-like protein (Lbp/Hlp) which reacts with sera from patients with Crohn's disease. Microbes Infect. 13:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wadström T, Ljungh A. 1999. Glycosaminoglycan-binding microbial proteins in tissue adhesion and invasion: key events in microbial pathogenicity. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bannantine JP, Wu CW, Hsu C, Zhou S, Schwartz DC, Bayles DO, Paustian ML, Alt DP, Sreevatsan S, Kapur V, Talaat AM. 2012. Genome sequencing of ovine isolates of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis offers insights into host association. BMC Genomics 13:89. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maccarana M, Sakura Y, Tawada A, Yoshida K, Lindahl U. 1996. Domain structure of heparan sulfates from bovine organs. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17804–17810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Temmerman ST, Place S, Debrie AS, Locht C, Mascart F. 2005. Effector functions of heparin-binding hemagglutinin-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in latent human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 192:226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parra M, Pickett T, Delogu G, Dheenadhayalan V, Debrie AS, Locht C, Brennan MJ. 2004. The mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin is a protective antigen in the mouse aerosol challenge model of tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 72:6799–6805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Bannantine JP, Zhang Q, Amonsin A, May BJ, Alt D, Banerji N, Kanjilal S, Kapur V. 2005. The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:12344–12349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorel MF, Krichevsky M, Levy-Frebault VV. 1990. Numerical taxonomy of mycobactin-dependent mycobacteria, emended description of Mycobacterium avium, and description of Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium subsp. nov., Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis subsp. nov., and Mycobacterium avium subsp. silvaticum subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 40:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mijs W, de Haas P, Rossau R, Van der Laan T, Rigouts L, Portaels F, van Soolingen D. 2002. Molecular evidence to support a proposal to reserve the designation Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium for bird-type isolates and ‘M. avium subsp. hominissuis' for the human/porcine type of M. avium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1505–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, III, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]