Abstract

In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), assessment of language lateralization is important as anterior temporal lobectomy may lead to language impairments. Despite the widespread use of fMRI, evidence of its usefulness in predicting postsurgical language performance is scant.

We investigated whether preoperative functional lateralization is related to the preoperative language performance, peri-ictal aphasia, and can predict language outcome one year post-surgery.

We studied a total of 72 TLE patients (42 left, 30 right), by using three fMRI tasks: Naming, Verb Generation and Fluency. Functional lateralization indices were analyzed with neuropsychological scores and presence of peri-ictal aphasia.

The key findings are:

-

1)

Both left and right TLE patients show decreased left lateralization compared to controls.

-

2)

Lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery. In left TLE, decreased left lateralization correlates with better fluency performance. In right TLE, increased left lateralization during the Naming task correlates with better naming.

-

3)

Left lateralization correlates with peri-ictal aphasia in left TLE patients.

-

4)

Lateralization correlates with language performance after surgery. In a subgroup of left TLE who underwent surgery (17 left), decreased left lateralization is predictive of better naming performance at 6 and 12 months after surgery.

The present study highlights the clinical relevance of fMRI language lateralization in TLE, especially to predict language outcome one year post-surgery. We also underline the importance of using fMRI tasks eliciting frontal and anterior temporal activations, when studying left and right TLE patients.

Keywords: Temporal lobe epilepsy, Language lateralization, Functional MRI, Temporal lobectomy

Highlights

-

•

We used preoperative fMRI to predict language performance in 72 TLE patients.

-

•

Language lateralization is clinically important for left and right TLE patients.

-

•

Lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery.

-

•

Left lateralization correlates with peri-ictal aphasia in left TLE.

-

•

Left lateralization predicts language performance 1 year after surgery in left TLE.

1. Introduction

In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) leads to effective treatment of seizures in 60–80% of drug-refractory cases (Tassi et al., 2009, Wiebe et al., 2001). However, ATL may cause language impairments, as anterior-middle temporal areas are involved in language processing and, in particular, naming (Baldo et al., 2012, Hamberger et al., 2007, Lambon Ralph et al., 2012, Trebuchon-Da Fonsa et al., 2009). After surgery, approximately 30% of left TLE (LTLE) patients show a significant decline in naming abilities (Davies et al., 1998, Stafiniak et al., 1990), persisting for up to one year (Langfitt and Rausch, 1996). A decline in verbal fluency has also been reported in 12–17% of LTLE patients (Helmstaedter et al., 2003). Postoperative language deficits have been occasionally reported also in right TLE (RTLE) patients (Bonelli et al., 2012, Helmstaedter et al., 2003, Rausch et al., 2003, Schwarz and Pauli, 2009). One critical factor in estimating the risk of postoperative language decline is the degree to which language processes are lateralized, typically to the left hemisphere (Wada and Rasmussen, 1960). Functional MRI (fMRI) is helpful in determining language lateralization and estimating the risk of postoperative decline (Berl et al., 2005, Bonelli et al., 2012, Sabsevitz et al., 2003, Wood et al., 2011), and is widely considered to be a valid noninvasive alternative to intracarotid amobarbital (Wada test; Klöppel and Büchel, 2005, Dym et al., 2011).

fMRI studies confirm and extend Wada test findings, revealing that LTLE patients typically have less left-lateralized language with respect to healthy controls in both frontal and temporal regions (Adcock et al., 2003). As regards RTLE patients, some studies have reported normal left lateralization (Adcock et al., 2003, Thivard et al., 2005), while others reported decreased lateralization, associated with additional recruitment of right frontal (Maccotta et al., 2007, Wong et al., 2009) and right temporal areas (Berl et al., 2005, Powell et al., 2007), depending on the fMRI task employed.

A number of studies have examined the relationship between fMRI activations and preoperative language performance in TLE patients (Berl et al., 2005, Bonelli et al., 2011, Bonelli et al., 2012, Noppeney et al., 2005, Wong et al., 2009), but little attention has been given to the relationship with lateralization. Berl et al. (2005) showed that in LTLE patients decreased left lateralization during response naming is associated with better naming and fluency performance, whereas in RTLE patients greater left-lateralization predicts better fluency scores (Berl et al., 2005).

Language functions are affected in TLE especially during seizures (Privitera and Kim, 2010). In LTLE, ictal and postictal language impairments (peri-ictal aphasia) occur in 75–82% of LTLE patients (Gabr et al., 1989, Koerner and Laxer, 1988) and are associated with left language dominance on the Wada test (Ramirez et al., 2008). LTLE patients without peri-ictal aphasia are therefore more likely to have atypical (i.e. bilateral or right) language dominance, but no fMRI data are available to date to substantiate this hypothesis.

Despite the established clinical relevance of language fMRI in presurgical evaluation in TLE, only a few studies have investigated its role in predicting postsurgical deficits. In preoperative LTLE patients, fMRI left-lateralization during semantic decision (Sabsevitz et al., 2003) and fluency (Bonelli et al., 2012) tasks was predictive of naming decline after ATL. However, in these studies, language was only assessed the first 6 months after surgery, while functional reorganization may continue over a longer time. Moreover, these studies relied on single language tasks, making it impossible to establish whether a paradigm may be more useful than others to predict postoperative deficits.

Evidence linking language lateralization to pre- and postoperative performance is therefore rather limited. It remains to be established whether commonly used tasks, such as fluency and naming, show lateralization differences that reflect varying levels of language performance. Moreover, no data are available regarding the value of preoperative fMRI in predicting outcome one year after surgery, when cognitive performance is generally more stable (Helmstaedter et al., 2003, Stafiniak et al., 1990), but some patients still show word-finding difficulties (Langfitt and Rausch, 1996). Finally, if stronger left-lateralization is confirmed to correlate with both peri-ictal aphasia and greater postoperative naming decline, peri-ictal aphasia itself might become a clinical index of postsurgical risk.

To address these issues, we used three language tasks commonly used in clinical fMRI: Naming, Verb Generation (VGen) and Verbal Fluency. We studied a total of 72 patients with TLE (42 LTLE and 30 RTLE), testing whether preoperative fMRI lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery. Second, we tested the hypothesis that LTLE patients with peri-ictal aphasia have stronger left lateralization in comparison to those without peri-ictal aphasia. Most importantly, in a subgroup of LTLE patients who underwent surgery (17 LTLE) we tested whether decreased left lateralization is associated with a favorable fluency and naming outcome 6 and 12 months after surgery.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

We studied patients with refractory TLE undergoing presurgical structural and functional imaging between 2007 and 2012 at the Fondazione IRCSS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy. Data from 72 Italian, right-handed unilateral TLE patients (42 LTLE and 30 RTLE) were retrospectively analyzed (Table 1). All imaging and clinical data were acquired and managed according to standard clinical procedures approved by the local institutional review board. In all patients, the epileptogenic zone was localized to the temporal lobe by clinical data, inter-ictal and ictal video-EEG, structural MRI and neuropsychological assessment. Handedness was determined with a standardized questionnaire (Oldfield, 1971). The LTLE and RTLE groups did not differ in age, sex, years of education, age at onset of epilepsy, epilepsy duration or in the percentage of seizure-free outcome (Engel's class I) after surgery (all p-values > 0.1). Fifteen native Italian-speaking subjects (median age 32 years, range 25–45 years, 9 females, mean education 16 years, all right handed) with no history of neurological or psychiatric disease were recruited as controls.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of TLE patients.

| LTLE |

RTLE |

|

|---|---|---|

| (n = 42) | (n = 30) | |

| Median (SD) age, years | 39 (10.3) | 36 (9.7) |

| Age range, years min-max | 20–58 | 21–57 |

| Sex, M/F | 20/22 | 16/14 |

| Mean education (SD), years | 11.6 (3.6) | 11.5 (3.9) |

| Mean age at onset (SD), years | 17.3 (11.0) | 14.0 (7.9) |

| Mean epilepsy duration (SD), years | 21.2 (16.0) | 24.2 (13.6) |

| MRI: | ||

| – Hippocampal Sclerosis | 10 | 12 |

| – Hippocampal Sclerosis + temporal lobe atrophy and blurring | 14 | 9 |

| – Focal cortical dysplasia without Hippocampal Sclerosis | 1 | 2 |

| – Glial-neural tumors (e.g. ganglioglioma, DNET) | 9 | 3 |

| – Other (e.g. gliosis) | 7 | 2 |

| – MRI normal | 1 | 2 |

| No. of patients in class I after surgery a | 27/29 (93%) | 15/20 (75%) |

According to the Engel's classification (Engel et al., 1993). Follow-up period at least 3 months (median 31, range 6–77 months).

A subgroup of 46 patients underwent left (28) or right (18) ATL. The epileptogenic zone, as determined on the basis of anatomo-electro-clinical correlations, and comprising the whole extent of the anatomic lesion (when identified on MRI), was removed. A maximum of 6.0 cm of the anterior lateral right temporal lobe or 4.5 cm of the left temporal lobe was resected. The cortical resection was performed “en bloc”, including, whenever necessary, the mesial temporal structures.

During presurgical evaluation, all patients underwent a preoperative battery of language fMRI tasks and standard neuropsychological assessment, which was repeated on the same patients 6 and 12 months after ATL. No patient underwent the Wada test.

2.2. Clinical assessment of peri-ictal language disturbances

For LTLE patients, the presence or absence of language disturbance during the ictal and postictal periods was evaluated by expert examiners through video-EEG recordings (21/42 cases): patients' spontaneous speech, naming of objects presented by the examiner (“what is this?” > a pen), their answers to simple questions (e.g. “where are we now?”) and to commands (e.g. “open your mouth”) were tested. Secondarily generalized seizures were not considered reliable because of the widespread diffusion of the epileptic discharge. When video-EEG data was not available, the presence or absence of language disturbances was evaluated through anamnestic information only if considered reliable (17/42 cases). Peri-ictal aphasia was identified when patients showed language deficits during the ictal phase only whenever contact with the external environment was maintained; otherwise, language was assessed during the post-ictal phase. Patients were considered not aphasic if they did not have any overt language deficits in the ictal and post-ictal phases. Patients without reliable data on language function during seizures were not considered (4/42 cases). All case histories were independently reviewed upon consensus of 3 neurologists (F.V., G.D., F.D.) blinded to the fMRI results.

Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests were used to determine whether LTLE patients with peri-ictal aphasia (n = 28) had a higher laterality index (LI, see below) than patients without peri-ictal aphasia (n = 10).

The sample of RTLE patients with peri-ictal language disturbance (n = 5), with lateralization data on a single fMRI task (n max = 4) and postoperative neuropsychological scores (n = 1) was too small to obtain reliable data, thus data were not reported.

2.3. Neuropsychological testing

Standard neuropsychological evaluation was performed before surgery and in the same patients at 6 and 12 months after surgery (Giovagnoli et al., 2005). This included the Boston Naming Test (Kaplan et al., 1983), letter and semantic verbal fluency tests. Normative data are available in Italian for the fluency tests (Novelli et al., 1986), but not for the Boston Naming Test, therefore a more conservative comparison has been made with a normative 60–64 year-old group with less than 12 years of education (Welch et al., 1996). Individual scores were compared to normative data using independent-sample t-tests.

In the subgroup of patients who underwent ATL, language performance change following surgery was calculated by subtracting the preoperative score from the postoperative score. Patients were classified as showing decline on the Boston Naming Test when change was equal to or larger than 5 points (Davies et al., 1998). A clinically meaningful decline on the fluency tasks was defined as a change of > 1 SD (Bonelli et al., 2012).

Preoperative scores of LTLE and RTLE patients, as well as changes in language scores at 6 and 12 months after surgery in LTLE only, were correlated with preoperative fMRI data.

2.4. MR data acquisition

Subjects were imaged on a Siemens Magnetom Avanto 1.5 T scanner, using an eight-channel phased-array head coil. Head movement was minimized with decompression cushions. A series of 100 functional volumes was acquired through a gradient-echo echo-planar sequence (TR = 4000 ms and TE = 52 ms). Twenty-five 4 mm oblique axial slices with 2 × 2 mm in-plane voxel size, aligned to the bicommissural plane, were acquired in interleaved order. Anatomical images were acquired with a magnetization-prepared gradient-echo volumetric T1-weighted sequence (1 mm3 isotropic voxels, TR = 1640 ms and TE = 2 ms). To confirm the attained coverage of the anterior-inferior temporal lobe, masks generated by SPM8's first level analysis function (see below) were summed across participants and the proportion of cases for which each voxel yielded measureable signal was calculated. As shown in Inline Supplementary Fig. S1, the lateral temporal gyri, particularly the superior and middle ones, were relatively free from dropout, however the most anterior ≈ 1 cm of the temporal pole was affected by dropout in the majority of cases.

Inline Supplementary Fig. S1.

Fig. S1.

Brain EPI sequence coverage map, presented as percent units over all participants and tasks. The lateral temporal gyri, particularly the superior and middle ones, were relatively free from dropout, however the most anterior ≈ 1 cm of the temporal pole was affected by dropout in the majority of cases.

2.5. fMRI tasks

Three language tasks were administered following a blocked design: Naming, Verb Generation (VGen) and Verbal Fluency (see Inline Supplementary Material for the description of each task). Stimuli were delivered visually using a back-projector and aurally using MRI-compatible headphones. All participants practiced each task before scanning.

Due to the retrospective nature of the present study, not all patients performed the three tasks; see Inline Supplementary Table S1 for details.

Inline Supplementary Table S1.

Table S1.

Number of LTLE and RTLE patients who performed the fMRI language tasks and who were also evaluated on neuropsychological language tests preoperatively, at 6-months and 12 months after surgery.

| LTLE (N = 42) |

RTLE (N = 30) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN | VG | FV | RN | VG | FV | |

| Preoperative | 30 | 27 | 21 | 15 | 17 | 15 |

| 6-month follow-up | 17 | 14 | 16 | – | – | – |

| 12-month follow-up | 17 | 14 | 15 | – | – | – |

2.6. Data analysis

FMRI data were analyzed using the SPM8 software (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging Department, London, UK) running under Matlab 7 (Mathworks, Natick, MA). After movement and slice-timing correction, functional images were co-registered with the corresponding anatomical scans, transformed into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and smoothed using an isotropic Gaussian kernel (FWHM 8 mm).

At the first level, condition-specific effects were estimated based on reference functions consisting of deconvolution of the task boxcars convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function. Six movement regressors were also included as nuisance covariates.

For the second-level group analysis, individual contrast images were entered into a one-sample t-test to examine the effects across each group (LTLE patients, RTLE patients and controls) and activations were reported at a significance level of p < 0.01 false-discovery rate (FDR) corrected, with an additional extent threshold of 10 voxels. Two-sample t-tests were then used to examine effects between groups, and activations were reported at a significance level of p < 0.005 uncorrected, with an extent threshold of 10 voxels.

2.7. Regions-of-interest (ROI) analysis

Anatomical ROIs corresponding to the inferior frontal gyrus, lateral temporal gyri (superior, medial and inferior temporal gyri, extending to the posterior temporal lobe) and temporal pole were selected from the Anatomical Automatic Labeling (AAL) atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) according to their relevance for language processing (Gaillard et al., 2004). In particular, the frontal area is a key-region in language lateralization, and the antero-medial temporal area is the target region for surgical resection.

For each ROI, the percentage of activated voxels was calculated at different thresholds: t > 1, t > 2, t > 3, t > 4 (e.g. Arora et al., 2009, Rosazza et al., 2009). Lateralization of fMRI activations was calculated using the laterality index (LI) formula: LI = [(xleft − xright) / (xright + xleft)]. Statistical analyses (including correlations, see below) were performed using the mid-range threshold t > 2, corresponding to voxel-level p < 0.05 uncorrected; as shown in the Results section, this threshold yielded an adequate compromise between detection of activity and minimization of spurious correlations. For t > 1 (corresponding to voxel-level p < 0.14) activations appeared excessively large and contaminated by artifacts, for t > 3 (corresponding to voxel-level p < 0.003) the voxel counts were insufficient to support the calculation of stable lateralization ratios (Inline Supplementary Fig. S2). The threshold t > 2 is also considered the most stable laterality measure in Arora et al. (2009). To explore the stability of the main findings with respect to threshold choice, the correlations at 6 and 12 months after surgery for LTLE patients were also calculated for t > 1 and > 3 (see below). Absolute values and LIs were analyzed with non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests, as data were not always normally distributed. A direct comparison between patients and controls was performed.

Inline Supplementary Fig. S2.

Fig. S2.

Results of the ROI-based analysis performed for the frontal and temporal regions for the three fMRI tasks. Measurements of the percentage of activated voxels for different threshold (t > 1, t > 2 and t > 3) are shown. Statistical analyses have been performed at t > 2. Mean and SE are reported.

2.8. Correlations between fMRI activations and neuropsychological performance

To examine the relationship between fMRI activations and language performance, robust linear regressions were performed between language scores and LIs (determined on the percentage of activated voxels at t > 2) in frontal and temporal ROIs and conducted separately for LTLE and RTLE patients. In order to restrict the analyses to the most informative correlations, the Boston Naming scores were used for the correlation analyses in all fMRI tasks, as the Boston Naming test shows the strongest language decline after surgery. In addition, for the Fluency fMRI task, the sum of the verbal fluency scores (semantic + letter fluency scores) collected outside the scanner was used for the correlation analysis, as it is the exact corresponding language score (Bonelli et al., 2012).

We tested for: 1. Correlations between LIs (from each of the three tasks) and their corresponding preoperative language scores for LTLE and RTLE patients; 2. Correlations between LIs and changes in the corresponding language scores 6 and 12 months after surgery only in LTLE patients. The RTLE group was too small to support reliable correlational analyses on postoperative data.

Finally, to determine the predictive power of the fMRI LIs beyond the baseline language score, a series of linear regression analyses were performed (Binder et al., 2008, Bonelli et al., 2010). The first variables entered in all analyses were preoperative scores, then the fMRI LIs were added to test whether fMRI LIs add significant predictive value in language at 6- and 12- months after surgery.

3. Results

3.1. fMRI results

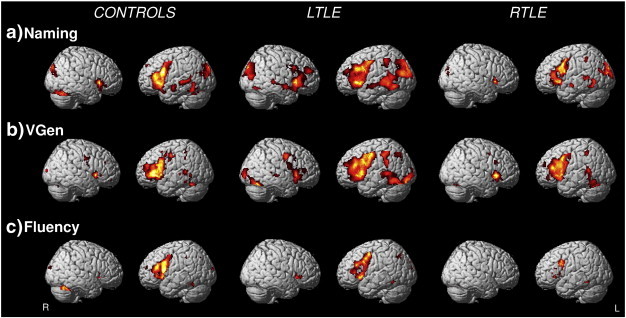

The overall activation pattern was left-lateralized in controls and patients for all tasks (Fig. 1 and see Inline Supplementary Table S2 for location of the activation peaks for fMRI contrasts of interest). Differences among tasks were mainly located in the temporal lobe. The Naming task (Fig. 1a) elicited activations in the anterior and posterior temporal regions, including the middle part of the superior temporal sulcus. In the VGen task (Fig. 1b) activations were observed mainly in the posterior lateral temporal regions and in the Fluency task (Fig. 1c) activations in the temporal lobe were limited.

Fig. 1.

Group average activation maps for healthy controls, LTLE and RTLE patients (p < .01, FDR corrected) during the Naming, Verb Generation (VGen) and Fluency tasks.

Inline Supplementary Table S2.

Table S2.

Location of the activation peaks for fMRI contrasts of interest. Voxel-level significance was set to p < 0.001 uncorrected. Cluster extent is expressed in 2x2x2 mm voxels.

| Group comparisons | Contrast | Peak coordinates MNI space (mm) | Z peak level | Cluster extent kE | q (FDR) cluster level | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | RN > VG | − 44, − 14, − 16 | 5.1 | 251 | 0.007 | Temporal Mid l |

| − 48, 36, 16 | 3.4 | 30 | ns | Frontal Inf Tri l | ||

| 44, − 16, − 14 | 3.6 | 43 | ns | Temporal Mid r | ||

| 56, − 2, − 14 | 3.2 | 10 | ns | Temporal Mid r | ||

| LTLE | RN > VG | − 50, − 14, − 10 | 4 | 157 | ns | Temporal Mid l |

| − 55, − 4, − 10 | 3.9 | 157 | 0.008 | Temporal Sup l | ||

| − 52, − 44, − 6 | 4.8 | 352 | 0.002 | Temporal Mid l | ||

| − 28, 30, 2 | 5.4 | 690 | < 0.001 | Insula l | ||

| − 48, 14, 18 | 3.8 | 428 | 0.001 | Frontal Inf Oper l | ||

| 56, 38, 12 | 3.9 | 99 | ns | Frontal Inf Tri r | ||

| 52, 12, − 18 | 3.6 | 338 | 0.002 | Temporal Pole Sup r | ||

| 60, − 4, − 10 | 4.75 | 338 | 0.002 | Temporal Sup r | ||

| RTLE | RN > VG | − 54, − 12, − 12 | 4.2 | 248 | 0.033 | Temporal Mid l |

| RTLE | VG > RN | 46, − 18, 10 | 3.6 | 43 | ns | Heschl r |

| 60, − 34, 26 | 3.6 | 82 | 0.05 | Temporal Sup r | ||

| 40, 18, 40 | 4.5 | 152 | 0.01 | Frontal Mid r | ||

| LTLE > RTLE | RN | − 52, − 44, − 2 | 3.1 | 31 | ns | Temp Mid l |

| 60, − 4, − 14 | 3.3 | 48 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| 56, 8, − 18 | 3.5 | 65 | ns | Temp Pole Mid r | ||

| 48, − 26, − 12 | 3.7 | 27 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| 38, 44, 20 | 3.2 | 24 | ns | Frontal Mid r | ||

| Controls > RTLE | RN | − 44, − 10, − 16 | 4.6 | 206 | ns | Temp Mid l |

| − 32, 26, 6 | 4.2 | 150 | ns | Hescl l | ||

| − 52, 14, 20 | 3.4 | 73 | ns | Front Inf Oper l | ||

| − 48, 30, 10 | 3.3 | 67 | ns | Front Inf Tri l | ||

| − 32, 16, − 14 | 3.4 | 64 | ns | Insula l | ||

| − 42, − 24, 2 | 3.2 | 154 | ns | Temp Sup l | ||

| − 54, − 32, − 6 | 2.7 | 64 | Ns | Temp Mid l | ||

| 48, − 26, − 10 | 3.3 | 52 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| Controls > LTLE | RN | − 40, 12, − 22 | 4.0 | 205 | ns | Temp pole sup l |

| − 48, − 10, − 10 | 3.7 | 361 | 0.03 | Temp Sup/Mid l | ||

| − 46, − 32, 4 | 3.2 | 21 | ns | Temp Sup l | ||

| − 34, 30, − 10 | 3.1 | 39 | ns | Frontal Inf Orb l | ||

| RTLE > LTLE | VG | − 55, − 45, − 12 | 2.8 | 38 | ns | Temp Mid l |

| 50, 40, − 12 | 3.3 | 41 | ns | Front Inf Orb r | ||

| 32, 58, − 6 | 3 | 41 | ns | Front Mid Orb R | ||

| 58, − 48, − 24 | 2.9 | 95 | ns | Temp Sup r | ||

| 48, − 52, 16 | 2.7 | 95 | ns | Temp Inf r | ||

| 66, − 28, 0 | 2.8 | 21 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| 66, − 40, − 6 | 2.7 | 6 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| RTLE > CTRL | VG | 42, 6, 44 | 4 | 499 | 0.018 | Frontal Mid r |

| 48, − 52, 14 | 3.7 | 269 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| 66, − 42, − 4 | 3.1 | 17 | ns | Temp Mid r | ||

| 52, − 60, − 12 | 3 | 113 | ns | Temp Inf r | ||

| Controls > RTLE | VG | − 50, 28, 10 | 3.6 | 75 | ns | Front Inf Tri l |

| − 42, 16, − 30 | 3.5 | 41 | ns | Temp Pole Mid l | ||

| − 52, − 4, − 12 | 3.0 | 25 | ns | Temp Sup l | ||

| 48, 14, − 22 | 2.6 | 5 | ns | Temp Pole Sup r | ||

| Controls > LTLE | VG | − 56, − 2, − 4 | 3.4 | 55 | ns | Temp Sup l |

| − 42, 48, 2 | 3.0 | 78 | ns | Front Mid Orb l | ||

| 42, 50, − 4 | 3.1 | 78 | ns | Front Mid orb r | ||

| 42, − 18, 10 | 4.0 | 276 | ns | Heschl r |

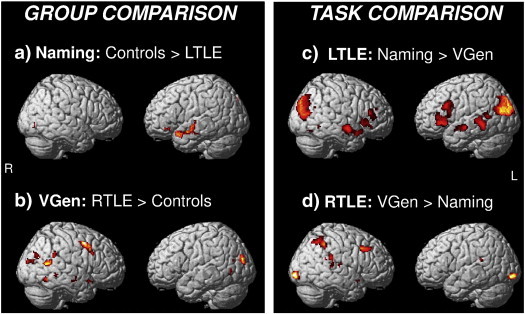

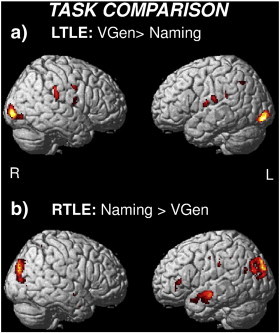

As regards differences between groups, during the Naming task the LTLE patients showed less activation than controls exclusively in the left anterior temporal lobe (Fig. 2a), while the contrast LTLE > controls did not reveal any significant difference. During the VGen task the RTLE patients showed greater activation than controls in the right hemisphere, in particular in the posterior temporal and middle frontal areas (Fig. 2b), while the contrast controls > RTLE revealed limited clusters of activation in the left frontal and temporal lobe.

Fig. 2.

Direct comparisons between groups and tasks (p < .005 uncorrected). a) During Naming, LTLE patients showed less activation than controls solely in the left anterior temporal lobe. b) During Verb Generation (VGen), RTLE patients showed greater activation than controls in the posterior temporal lobe, particularly on the right side. c) The Naming > VGen contrast for the LTLE group revealed bilateral differences in temporal and frontal activity. d) The VGen > Naming contrast for the RTLE group revealed greater right hemisphere activity in the posterior temporal region.

As regards differences between tasks, the Naming > VGen contrast for the LTLE group produced bilateral differences in the anterior-middle temporal regions (Fig. 2c), revealing a bilateral engagement of the temporal lobes for the Naming task, while the VGen > Naming contrast revealed limited activations in the occipital regions and in the perisylvian areas (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S4a). The VGen > Naming contrast for the RTLE group revealed right hemisphere activations in the posterior temporal region and in the middle frontal region (Fig. 2d). The reverse Naming > VGen contrast revealed a significant cluster of activation in the left anterior temporal lobe (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S4b).

Inline Supplementary Fig. S4.

3.2. ROI analysis and laterality index (LI)

As regards fMRI hemispheric activity, ROI analysis showed decreased left frontal activation in all patients and right hemisphere recruitment in particular in LTLE patients during the Naming task and in RTLE patients during the VGen task (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S2 and associated text in the Inline Supplementary Material).

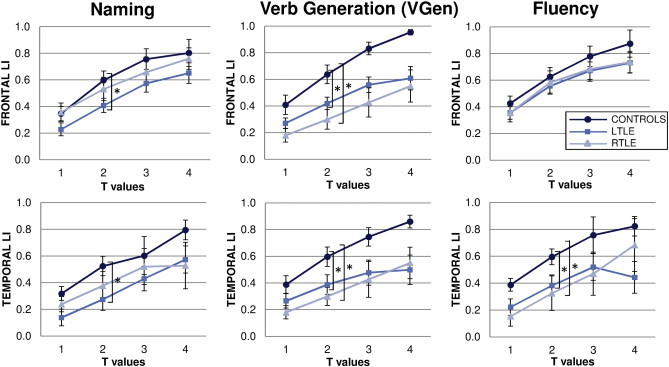

As regards lateralization, for the Naming task, the LIs showed decreased left-lateralization for LTLE patients in the frontal (t = − 1.96, p = .05) and temporal (t = 2.13, p < .05) ROIs compared to controls, which persisted at different thresholds (Fig. 3). The RTLE patients did not differ from controls.

Fig. 3.

Dependence of the laterality indices (LI) on the statistical threshold, shown separately for each ROI and task. The LI is threshold-dependent, but differences among groups are robust with respect to threshold choice; t > 2 was chosen for statistical analyses (see text for details). Superscript “*” denotes statistically significant difference between groups. LI showed a generally weaker left-lateralization for LTLE and to less extent for RTLE than controls in all tasks.

Similarly, on the VGen task, LTLE patients showed weaker left-lateralization in the frontal (t = 2.6, p < .05) and temporal (t = 2.1, p < .05) ROIs compared to controls. Surprisingly, RTLE patients displayed even weaker left-lateralization than controls in both frontal (t = 3.3, p < .005) and temporal (t = 2.9, p < .01) ROIs, independent of threshold choice.

For the Fluency task, patients did not differ from controls in the frontal ROI, whereas in the temporal ROI both LTLE and RTLE patients showed decreased left-lateralization (t = 2, p < .05 and t = 2.6, p < .05) persisting at all thresholds.

For both LTLE and RTLE patients, left lateralization was lower for the temporal than the frontal ROIs in the Naming task, while in the VGen task the LIs were similar between the frontal and temporal ROIs.

No correlations were found between fMRI LIs and age of onset of epilepsy in any task.

3.3. Language lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery

3.3.1. Neuropsychological performance

Before surgery, LTLE and RTLE patients generally had significantly lower scores than normative data on language tasks (Table 2).

Table 2.

Preoperative, 6 and 12-month follow-up performance on the language tests, the number and percentage (in bold) of LTLE and RTLE patients who showed a clinically significant decline after surgery. The number of patients who performed the tests (N) with mean and standard deviation (SD) of the scores is reported for each test. The p-values represent the comparison with respect to normative data.

| LTLE |

RTLE |

Normative data |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | p-value | N | Mean (SD) | p-value | Mean (SD) | |

| Boston Naming test | |||||||

| Preoperative | 41 | 43.6 ± 8.8 | < .02 | 27 | 46.7 ± 7.2 | n.s. | 49.8 ± 5.4 |

| 6 month follow-up | 26 | 39.6 ± 11.3 | < .0003 | 13 | 48.2 ± 7.6 | n.s. | |

| N (%) declining at 6 months | 10(38%) | 0 | |||||

| 12 month follow-up | 24 | 42.5 ± 11.2 | < .03 | 15 | 49.2 ± 7.2 | n.s. | |

| N (%) declining at 12 months | 5(21%) | 1(7%) | |||||

| Semantic Fluency | |||||||

| Preoperative | 39 | 33.4 ± 10.6 | < .0001 | 28 | 36.3 ± 9.0 | < .03 | 40.62 ± 7.8 |

| 6 months follow-up | 25 | 33.7 ± 12.1 | < .01 | 17 | 32.8 ± 9.7 | < .003 | |

| N (%) declining at 6 months | 4(16%) | 4(24%) | |||||

| 12 months follow-up | 22 | 33.8 ± 11.8 | < .01 | 18 | 34.4 ± 8.5 | < .01 | |

| N (%) declining at 12 months | 2(9%) | 3(18%) | |||||

| Phonemic Fluency | |||||||

| Preoperative | 39 | 26.1 ± 10.6 | < .0001 | 26 | 28.0 ± 11.4 | < .02 | 33.96 ± 9.1 |

| 6 month follow-up | 25 | 27.1 ± 9.7 | < .01 | 16 | 27.2 ± 12.9 | < .05 | |

| N (%) declining at 6 months | 2(8%) | 1(6%) | |||||

| 12 month follow-up | 22 | 30.2 ± 8.1 | .072 | 17 | 28.4 ± 11.6 | 0.07 | |

| N (%) declining at 12 months | 2(9%) | 2(12%) | |||||

3.3.2. Correlation between fMRI activations and preoperative performance

Linear regressions between fMRI language LIs and corresponding neuropsychological scores were performed for the three fMRI tasks (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between fMRI language LIs in the frontal and temporal ROIs (from the Naming, the Verb Generation (VGen) and the Fluency tasks) and the preoperative language scores. The Boston Naming scores were used in the correlation analyses for all fMRI tasks. In addition, for the Fluency fMRI task, the verbal fluency scores were used in the correlation analysis, as they are the exact corresponding language score. In bold the significant correlations.

| Frontal LI |

Temporal LI |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI tasks | Language score | N | r | p | r | p | |

| LTLE | Naming | Naming | 30 | − 0.05 | n.s. | − 0.23 | 0.23 |

| VGen | Naming | 27 | − 0.02 | n.s. | 0.13 | n.s. | |

| Fluency | Naming | 21 | − 0.36 | 0.1 | − 0.04 | n.s. | |

| Fluency | Fluency | 21 | − 0.48 | 0.02 | − 0.17 | n.s. | |

| RTLE | Naming | Naming | 15 | 0.63 | 0.01 | − 0.10 | n.s. |

| VGEN | Naming | 17 | − 0.46 | 0.1 | − 0.58 | 0.01 | |

| Fluency | Naming | 15 | 0.1 | n.s. | 0.57 | 0.03 | |

| Fluency | Fluency | 15 | 0.02 | n.s. | 0.31 | 0.26 | |

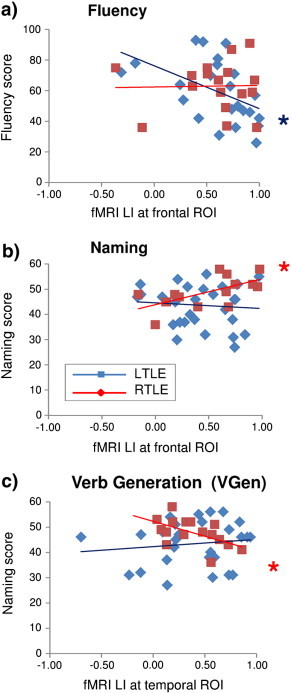

For RTLE patients, in the Naming task, LI in the frontal ROI correlated positively with the Boston Naming score (r = 0.64, p < 0.05), as well as in the Fluency task the temporal ROI correlated positively with the Boston Naming score (r = 0.57, p < 0.05), both evidence indicating that stronger lateralization towards the left hemisphere was associated with better language performance (see Inline Supplementary Figs. S3b and S4b). Instead, in the VGen task, LI in the temporal region correlated negatively with the Boston Naming score (r = − 0.55, p < 0.05), indicating that in this task stronger left-lateralization was associated with worse language performance (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S3c).

Inline Supplementary Fig. S3.

Fig. S3.

Correlation between fMRI laterality index (LI) at frontal and temporal ROIs and preoperative language scores for LTLE and RTLE patients. For LTLE patients, (a) decreased left lateralization in the Fluency task was associated to better fluency performance. For RTLE patients, better naming was related to (c) stronger left frontal lateralization in the Naming task and (d) bilateral temporal activation in the Verb Generation (VGen) task.

Fig. S4.

Direct comparisons between tasks (p < .005 uncorrected). a) The VGen > Naming contrast for the LTLE group reveals limited activations in the occipital and perisylvian areas. b) The Naming > VGen contrast for the RTLE group reveals a significant cluster of activation in the anterior temporal region.

For LTLE patients, in the Fluency task, LI in the frontal ROI correlated negatively with fluency score (r = − 0.48, p < 0.05), indicating that decreased left-lateralization was associated with better fluency performance (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S3a).

3.4. Left lateralization correlates with peri-ictal aphasia in LTLE patients

LTLE patients without peri-ictal aphasia showed weaker left-lateralization than those with perictal aphasia (Table 4). The effect was significant for the frontal region in the Fluency and Naming tasks (Z = − 2.3, p < .05 and Z = − 1.9, p = 0.05, respectively) and there was a trend for the temporal region in the Fluency task (Z = − 1.87, p = .065). The number of LTLE patients who declined on naming at 6 and 12 months after surgery was higher in the group of aphasics than in the group of non-aphasics, even though the difference was not statistically significant. The two groups did not differ in age of onset and duration of epilepsy, and there were no differences in the preoperative neuropsychological language scores.

Table 4.

Language manifestation in LTLE patients (N = 42). Language manifestations were classified as a) peri-ictal aphasia or b) no peri-ictal aphasia. Patients were not considered when video-EEG was not available and anamnestic data unreliable (see text). For each group, the number and percentage of patients, the corresponding laterality index (LI) in the Fluency, Naming and Verb Generation (VGen) tasks, and the percentage of patients with naming decline at 6 and 12 months after surgery are reported.

| Language manifestation | No. of patients (%) | No. of patients with vEEG (%) | Fluency frontal LI (N) | Fluency temporal LI (N) | Naming frontal LI (N) | Naming temporal LI (N) | VGen frontal LI (N) | VGen temporal LI (N) | % of patients with naming decline at 6 and 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Peri-ictal aphasia | 28/42 (67%) | 16/21 (76%) | 0.65 (17) | 0.47 (17) | 0.50 (21) | 0.32 (21) | 0.45 (21) | 0.39 (21) | 47% 27% |

| b) No peri-ictal aphasia | 10/42 (24%) | 5/21 (24%) | 0.26 (7) | 0.25 (7) | 0.29 (8) | 0.32 (8) | 0.37 (5) | 0.41 (5) | 29% 17% |

| Removed | 4/42 (10%) | ||||||||

| a) vs. b) | p < 0.05 | p = .061 | p = 0.05 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

3.5. Decreased left lateralization correlates with better language outcome after surgery in LTLE

3.5.1. Neuropsychological performance

After surgery, LTLE patients showed a decline in naming abilities, relative to their preoperative scores. In particular, 38% of cases had clinically significant decreased scores at 6 months and 21% at 12 months after surgery. For the Fluency tests, 8–16% of LTLE patients showed a clinically significant decline at 6 months and 9% at 12 months after surgery, relative to their preoperative scores (see Table 2).

For RTLE patients, the group means before and after surgery were not significantly different for the language tasks. Interestingly, on the Semantic Fluency test, four RTLE patients (24% of cases) had clinically significant decreased scores at 6 months and 3 cases (21% of cases) at 12 months after surgery, relative to their preoperative scores. One RTLE patient significantly declined on all language tests administered at 6 and 12 months after surgery.

3.5.2. Correlation between preoperative fMRI activations and postsurgical language performance in LTLE

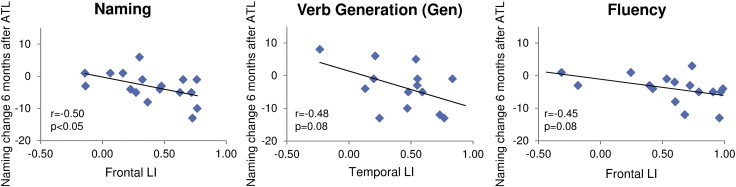

Linear regressions between fMRI LIs and changes in neuropsychological scores after 6 and 12 months from ATL were performed for the three tasks.

As reported in Table 5, in LTLE decreased left lateralization in the frontal ROI was significantly correlated with better naming outcome 6 months after ATL for the Naming task (r = − 0.50, p < 0.05), and there was a strong trend for the VGen task (r = − 0.48, p = 0.08) and the Fluency task (r = − 0.45, p = 0.08). In Fig. 4 the most important correlations are reported. Decreased left lateralization in the frontal ROI was significantly correlated with better fluency outcome 6 months after ATL for the Fluency task (r = − 0.52, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

For LTLE patients, correlations between fMRI language LIs in the frontal and temporal ROI (from the Naming, Verb Generation (VGen) and Fluency tasks) and post- vs. pre-operative changes on language scores, assessed 6 and 12 months after surgery. The Boston Naming outcome was used in the correlation analyses in all fMRI tasks, as the Boston Naming test shows the strongest language decline after surgery in LTLE patients. In addition, for the Fluency fMRI task, the verbal fluency outcome was used in the correlation analysis, as it is the exact corresponding language score. In bold the significant correlations and trends.

| Language outcome 6 months after ATL |

Language outcome 12 months after ATL |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI tasks | Language outcome | LI | N | r | p | N | r | p |

| Naming | Naming | Frontal | 17 | − 0.50 | 0.04 | 17 | − 0.66 | 0.004 |

| Temporal | − 0.26 | 0.29 | − 0.29 | 0.26 | ||||

| VGen | Naming | Frontal | 14 | − 0.46 | 0.10 | 14 | − 0.52 | 0.056 |

| Temporal | − 0.48 | 0.08 | − 0.58 | 0.04 | ||||

| Fluency | Naming | Frontal | 16 | − 0.45 | 0.08 | 15 | − 0.73 | 0.003 |

| Temporal | − 0.09 | n.s. | − 0.29 | n.s. | ||||

| Fluency | Fluency | Frontal | 16 | − 0.52 | 0.03 | 15 | − 0.37 | 0.16 |

| Temporal | − 0.32 | 0.2 | − 0.38 | 0.16 | ||||

Fig. 4.

Relationship between fMRI laterality indices (LIs) for the frontal and temporal ROIs and post- vs. pre-operative changes on naming scores, assessed 6 months after surgery in LTLE patients. These are the most important correlations, as reported in Table 5. In LTLE, decreased left-lateralization in the Naming tasks was associated with better naming performance 6 months after ATL and there was a strong trend for the VGen task and the Fluency task.

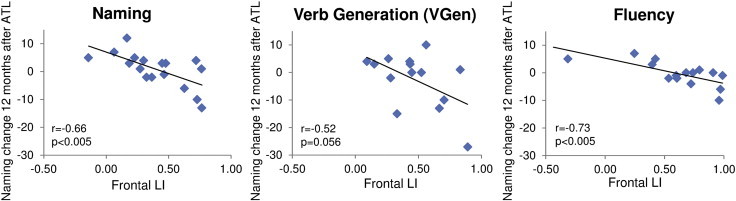

Twelve months after ATL, lateralization was related only to naming decline (Fig. 5): greater decline in naming was associated with stronger frontal left-lateralization in all fMRI tasks (Naming: r = − 0.66, p < .005; VGen: r = − 0.52, p = .056; Fluency: r = − 0.73, p < .005;) and stronger temporal left-lateralization in the VGen task (r = − 0.58, p < 0.05). Correlations at 6 and 12 months after surgery were confirmed also for t > 1 and t > 3 (see Inline Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 5.

Relationship between fMRI laterality indices (LIs) for the frontal and temporal ROIs and post- vs. pre-operative changes on naming scores, assessed 12 months after surgery in LTLE patients. These are the most important correlations, as reported in Table 5. In LTLE, decreased left lateralization in all fMRI tasks was associated with better naming 12 months after ATL.

Inline Supplementary Table S3.

Table S3.

Correlations between preoperative fMRI LIs and postsurgical language performance, assessed 6 and 12 months after surgery for LTLE patients, calculated for t > 1 and t > 3, in addition to t > 2, reported in Table 5 in the manuscript.

| Language outcome 6 months after ATL |

Language outcome 12 months after ATL |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI tasks | Language outcome | LI | r | p | r | p |

| t > 1 | ||||||

| Naming | Naming | Frontal | − 0.49 | 0.04 | − 0.78 | 0.000 |

| Temporal | − 0.26 | n.s. | − 0.21 | n.s. | ||

| VGen | Naming | Frontal | − 0.27 | n.s. | − 0.61 | 0.04 |

| Temporal | − 0.16 | n.s. | − 0.45 | 0.09 | ||

| Fluency | Naming | Frontal | − 0.57 | 0.03 | − 0.73 | 0.002 |

| Temporal | 0.14 | n.s. | − 0.30 | n.s. | ||

| Fluency | Fluency | Frontal | − 0.67 | 0.001 | − 0.30 | n.s. |

| Temporal | 0.05 | n.s. | − 0.20 | n.s. | ||

| t > 3 | ||||||

| Naming | Naming | Frontal | − 0.66 | 0.007 | − 0.69 | 0.003 |

| Temporal | − 0.27 | 0.28 | − 0.39 | 0.15 | ||

| VGen | Naming | Frontal | − 0.68 | 0.01 | − 0.54 | 0.045 |

| Temporal | − 0.51 | 0.06 | − 0.43 | 0.11 | ||

| Fluency | Naming | Frontal | − 0.56 | 0.03 | − 0.58 | 0.02 |

| Temporal | − 0.14 | n.s. | − 0.02 | n.s. | ||

| Fluency | Fluency | Frontal | − 0.51 | 0.04 | − 0.14 | n.s. |

| Temporal | − 0.37 | 0.14 | − 0.30 | n.s. | ||

While the RTLE group was too small to perform correlational analyses, four patients declined postoperatively on a single or multiple language tasks (Table 2). Three patients displayed atypical lateralization: two of them showed decreased left frontal lateralization during the Naming task, and a case who declined on all tasks showed left-frontal and right-temporal lateralization during the Naming task and a bilateral pattern during the VGen task. Their Engel's classification was class I for two patients and class II for the other two cases, without any particular event in their clinical history.

3.6. Multifactorial prediction of language outcome

Linear regression analyses were performed with postoperative language outcome as dependent variable (6- and 12-month outcome in separate analyses) and with preoperative score, fMRI frontal and temporal LIs as independent variables for all three fMRI tasks (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Multifactorial prediction models of language outcome in LTLE patients. The fMRI LIs are significant predictors of language outcome at 6 and 12 months after ATL.

| R2 |

Model p-value |

Predictor p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | |||

| Naming | ||||

| 6-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.83 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.91 | < .0001 | < .005 | = .05 |

| 12-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.63 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.82 | < .0001 | < .005 | n.s. |

| Verb generation | ||||

| 6-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.43 | < .008 | < .008 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.79 | < .002 | n.s | n.s |

| 12-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.38 | < .02 | < .02 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.80 | < .003 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Fluency | ||||

| 6-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.87 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.89 | < .0001 | n.s. | n.s. |

| 12-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative Boston Naming test score | 0.86 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI and temporal LI | 0.93 | < .0001 | < .05 | n.s. |

| Fluency | ||||

| 6-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative fluency score | 0.66 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI | 0.76 | < .0001 | < .03 | |

| 12-month language outcome | ||||

| Preoperative fluency score | 0.79 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| Add fMRI frontal LI | 0.84 | < .0001 | = .08 | |

In the group of patients who performed the Naming task (n = 17), the preoperative language score (Boston Naming test) accounted for 83% and 63% of the variance in outcome at 6- and 12-months after surgery, respectively. When the fMRI LIs were included as well, these values increased to 91 and 82%, with frontal LI making a significant contribution at 6 and 12 months (p < .0005), and the temporal LI only at 6 months (p = .05).

In the group of patients who performed the VGen task (n = 14), the preoperative language score (Boston Naming test) accounted for 43% and 38% of the variance in outcome at 6- and 12-months after surgery, respectively. When the fMRI LIs were included as well, these values increased to 79 and 80%, although fMRI LI did not make significant contributions.

In the group of patients who performed the Fluency task (n = 16), the preoperative language score (Boston Naming test) accounted for 87% and 86% of the variance in outcome at 6- and 12-months after surgery, respectively. When the fMRI LIs were included as well, these values increased to 89 and 93%, with frontal LI making a significant contribution at 12 months (p < .05).

When the Fluency task was associated to its corresponding fluency scores, the preoperative score accounted for 66% and 79% of the variance in outcome at 6- and 12-months after surgery, respectively. When the fMRI frontal LI was included as well, these values increased to 76 and 84%, with frontal LI making a significant contribution at 6 months (p < .05) and with a strong trend at 12 months (p = .08). Here, the temporal LI was not included, as the frontal areas are the only regions typically considered informative for a fluency task.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to characterize the language fMRI activation pattern in patients with LTLE and RTLE, investigating whether lateralization is related to naming and fluency performance before surgery, to peri-ictal aphasia, and whether it can predict language outcome 6 and 12 months after surgery. The findings can be summarized in four main points:

-

1)

Both LTLE and RTLE patients show decreased left-lateralization with respect to controls;

-

2)

Lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery;

-

3)

Left lateralization correlates with peri-ictal aphasia in LTLE patients;

-

4)

Decreased left lateralization correlates with better language performance after surgery in a subgroup of LTLE patients.

4.1. Reduced left lateralization in LTLE and RTLE patients

LTLE and RTLE patients showed decreased left-lateralization for language compared to controls (Fig. 3); this was most evident in LTLE patients during the Naming task, and in RTLE patients during the VGen task.

In LTLE patients, atypical (decreased) lateralization has been widely reported in Wada test and fMRI studies (Adcock et al., 2003, Powell et al., 2007, Springer et al., 1999, Thivard et al., 2005). Chronic epileptic activity as well as its pathological cause are known to have deleterious effects on left hemisphere language processing and can induce a partial shift of language-related areas to the right hemisphere (Berl et al., 2005, Janszky et al., 2003, Weber et al., 2006a).

Here, the three fMRI tasks produced different lateralization patterns in LTLE patients compared to controls, with important implications for presurgical planning. In particular, the Naming and VGen tasks revealed decreased left lateralization in both frontal and temporal regions in LTLE patients compared to controls (Fig. 3), due to a combination of reduced ipsilateral and greater contralateral activations (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S2), which, to our knowledge, has not been reported in literature (e.g. Adcock et al., 2003, Powell et al., 2007, Thivard et al., 2005).

RTLE patients showed decreased left lateralization in particular during the VGen task, where right posterior temporal activations were observed (Fig. 2b and d). Patients with RTLE have generally received less attention in previous studies, since language dominance is expected to be lateralized to the left hemisphere and right ATL is deemed to pose minor risks. However, Wada test studies have occasionally reported increased incidence of atypical language dominance in RTLE patients as compared to normal subjects, ranging from approximately 7% to 30% of cases (Deblaere et al., 2004, Helmstaedter et al., 1997, Lehéricy et al., 2000, Rutten et al., 2002); this finding was also confirmed by some fMRI studies (Springer et al., 1999, Thivard et al., 2005). Paradoxical recruitment of right frontal and temporal regions has also been observed in fMRI studies (Berl et al., 2005, Cunningham et al., 2008, Vitali et al., 2011, Wong et al., 2009). In contrast to LTLE, atypical language dominance in RTLE is suggestive of higher risk of postsurgical language deficits. In our study, four RTLE patients declined one year after surgery (Table 2) and three of them displayed atypical dominance in the Naming task. This suggests that the assessment of language lateralization may be also indicated for this group.

4.2. Lateralization correlates with language performance before surgery

In LTLE, decreased left frontal lateralization during the verbal (letter and semantic) fluency task was associated with better verbal (letter and semantic) fluency performance (Table 3 and see Inline Supplementary Fig. S3a). This correlation is expected, given that the shift towards the right hemisphere decreases the interference between language areas and left hemispheric epileptic focus. This is also consistent with the only, to our knowledge, existing fMRI evidence of decreased inferior frontal lateralization correlating with better verbal IQ (Berl et al., 2005).

In RTLE patients, increased frontal left-lateralization during the Naming task and increased temporal left-lateralization during the Fluency task was associated with better preoperative naming performance (Table 3 and see Inline Supplementary Fig. S3b). These correlations, opposite to that observed in LTLE, are expected, given that left lateralization keeps the language areas away from interference by the right hemispheric epileptic focus (see Inline Supplementary Fig. S4b). However, during the VGen task, decreased left lateralization was observed (Fig. 2b and d) and associated with better preoperative naming performance (Table 3 and see Inline Supplementary Fig. S3c). The right posterior temporal regions are normally involved in semantic-lexical processing (Binder et al., 2009, Hickok and Poeppel, 2007, Tomasino et al., 2011), but here are more activated in RTLE patients than in controls: this might be a compensatory mechanism related to language, recruited to cope with the pathology. Alternatively, it might be related to a more general attentional-executive dysfunction (Bocquillon et al., 2009, Messas et al., 2008, Stella and Maciel, 2003). This increased activation is not expected in RTLE, given that a shift toward the right hemisphere should increase interference by epileptic activity. A possible explanation of this apparently paradoxical phenomenon is that interference is actually minimal, as the temporal activations are very posterior, close to the planum temporalis and supramarginal gyrus: increased ipsilateral activation may be more efficient than shift to the contralateral hemisphere.

The sample of RTLE patients who completed the language tests after ATL was too small to perform correlation analyses, therefore further research is necessary to establish the most suitable task for predicting postsurgical deficits.

4.3. Left lateralization correlates with peri-ictal aphasia in LTLE patients

LTLE patients without peri-ictal aphasia had significantly decreased frontal lateralization, while those with peri-ictal aphasia had typical left frontal lateralization. This suggests that in LTLE patients with peri-ictal aphasia, the left hemispheric focus keeps interfering with the frontal areas, whereas in patients without peri-ictal aphasia, recruitment of contralateral regions eludes this interference. In the latter group, a more bilateral activation pattern tended to be associated with lower risk of naming performance decline (Table 4). Previous studies have shown that ictal and postictal language dysfunction is correlated to language dominance, as determined by the Wada test (Gabr et al., 1989, Janszky et al., 2003, Koerner and Laxer, 1988, Privitera et al., 1996). To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a relationship between fMRI lateralization and peri-ictal language disturbances.

4.4. Decreased left lateralization correlates with better language performance after surgery in a subgroup of LTLE patients

The neuropsychological assessment revealed that after surgery 38% of LTLE patients declined in naming performance at 6 months, and 21% at 12 months (Table 2), in line with previous reports (Bonelli et al., 2012, Langfitt and Rausch, 1996). Fluency was less affected by surgery: ~ 9% of LTLE and ~ 18% of RTLE patients showed a significant decline in verbal fluency 12 months after ATL, in line with previous studies (Bonelli et al., 2012, Helmstaedter et al., 2003). However, a previous study revealed that the decline in verbal fluency persists at least for up to 10 years after surgery for ~ 17% of LTLE and RTLE patients (Helmstaedter et al., 2003). In RTLE patients, postoperative attentional-executive deficits are also reported, which may also contribute to language deficits (Helmstaedter et al., 2003, Rausch et al., 2003). The decline in verbal fluency has generally been less considered than the decline in naming, but it suggests a cognitive loss, persisting several years after surgery and it is worth examining more closely.

As regards the prediction of language decline, in LTLE patients stronger preoperative left lateralization was predictive of naming decline at 6 and 12 months after ATL with all fMRI tasks (Table 5, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Left lateralization on the Fluency task was also predictive of poorer fluency outcome only at 6 months.

fMRI lateralization was shown to have a consistent predictive power beyond the baseline language score in each fMRI task (Table 6), as reported by Binder et al. (2008). Preoperative performance accounted for ~ 68% of the variance in postoperative language performance at 6 and 12 months after surgery in the three fMRI tasks, and fMRI explained an additional ~ 16% of this variance.

The correlation at 6 months confirms the results by Sabsevitz et al. (2003) and Bonelli et al. (2012), showing that if language is lateralized to the left hemisphere, it is likely to be compromised after ATL, while if lateralization is decreased and language is supported by both left and right hemispheres, left ATL should not lead to significant language deficits. Our investigation extends these findings through the use of three fMRI paradigms, showing that all the three fMRI tasks can predict naming deficits at 12 months after ATL. In addition, our results suggest that the fMRI Naming task, which elicits anterior temporal activations and is more related to naming, has a more consistent predictive value, considering the correlations at 6 and 12 months (Table 5) and its significant predictive power beyond the neuropsychological baseline score (Table 6). Importantly, correlations at 6 and 12 months after surgery remained significant also when different thresholds were used (see Inline Supplementary Table S3), demonstrating that the results are robust with respect to threshold choice. Finally, here we considered a longer clinical follow-up, exceeding all previous investigations we are aware of.

4.5. Clinical implications and limitations

The key findings of this study reveal the clinical importance of decreased left language lateralization, which differs for LTLE and RTLE patients.

In LTLE, the shift toward the right hemisphere is an efficient means of preserving language by relocating it away from the epileptic focus. For the first time decreased left lateralization has been shown to be a global benefit in LTLE, being related to better preoperative language performance (in the Fluency task), to less peri-ictal language disturbances, and to better postoperative language performance, 6 and 12 months after surgery. The presence of peri-ictal language dysfunction in LTLE may indicate left dominance, associated to higher risk of postoperative deficits.

In RTLE, the occasionally-observed shift toward the right hemisphere, close to the epileptic focus and surgical resection, is suggestive of higher risk of postsurgical language deficits. Generally, postoperative language deficits, when observed, are not as marked as in LTLE patients and are also less predictable (Rausch et al., 2003). Therefore, language fMRI is suggested even in presurgical evaluation of RTLE patients.

This study shows that lateralization can vary according to the fMRI task employed, as previously reported (Gaillard et al., 2004), therefore at least two fMRI tasks are recommended to assess language lateralization in LTLE and RTLE patients. In particular, fMRI tasks such as Naming are useful to explore the network supporting naming processes because they elicit both frontal and anterior temporal areas.

An important question regards whether frontal or temporal activity is a more reliable substrate in the prediction of postsurgical language deficits. In our study frontal regions predicted naming deficits for all fMRI tasks, while temporal regions predicted naming deficits only in the VGen task. In addition, frontal regions predicted fluency deficits, and generally appeared more stable than temporal regions in predicting language outcome. A possible explanation for this observation is that frontal activity is more easily detected in comparison to activity in antero-lateral temporal regions, which can be masked by susceptibility artifacts, therefore frontal lateralization is statistically more robust than temporal lateralization. Another possible explanation is that the Naming task included an auditory condition, which could be better suited to activate bilateral temporal networks. Overall, frontal regions appear more stable to predict language deficits, but also result to be in close connection with temporal areas (Maccotta et al., 2007). Our results suggest that temporal activations in particular in the more anterior area should be considered carefully in the preoperative assessment, even if no study has demonstrated yet that resection of activated voxels is correlated with language decline.

The present study has a number of limitations. First, our findings relate to a relatively small sample of patients and require confirmation in larger groups. We only included right handed participants, and the sample size did not allow us to fully investigate the influence of other potentially important factors, such as age of onset and duration of epilepsy. This limitation is common with other studies in this area (e.g., Powell et al., 2007, Sabsevitz et al., 2003). Second, patients and controls did not differ in age (p > 0.1), while controls had higher educational level than patients (p < .001). Even if we cannot exclude an influence of this factor on fMRI language tasks, education level did not have effects on medial temporal lobe activation in an episodic memory task (Yousem et al., 2009). Third, we did not record in-scanner behavioral data, since the Fluency and VGen tasks were performed silently and the Naming task was only assessed qualitatively in terms of whether patients performed the task verbalizing the required words. However, Weber et al. (2006b) showed that task performance affected volume of activation but much less lateralization; moreover, this limitation is in common with several studies (Binder et al., 2008, Bonelli et al., 2012, Sabsevitz et al., 2003, Wong et al., 2009). Another limitation is the signal distortion and dropout in the anterior inferior temporal lobes, in particular the temporal poles and basal cortex overlying the petrous bone. Due to this limitation, our results on temporal pole activations should be interpreted with caution and future work using optimized acquisition schemes is necessary (Binney et al., 2010). Further, the surgeon planned the extent of resection taking into account the fMRI maps and this might have influenced the results (Binder et al., 2011). Finally, correlation between post-operative outcome and resected volumes was not investigated; future work will need to evaluate the effects of resection volume, measured on segmented post-operative structural scans, on post-operative performance.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the importance of preoperative fMRI in predicting language outcome one year after ATL and highlights the clinical relevance of decreased language lateralization. In LTLE decreased left lateralization seems to be an effective compensatory mechanism which protects language functions by shifting them away from interictal and ictal epileptic activity before surgery, and protects from postsurgical naming deficits for up to one year after surgery.

In RTLE the occasionally-observed decreased left-lateralization may lead to an increased risk of postsurgical deficits. Finally, our results suggest that all fMRI tasks have a good predictive value for naming performance at 12 months for LTLE patients. The use of more than one fMRI task eliciting frontal as well as anterior temporal activations such as the Naming task is strongly advised, when studying both LTLE and RTLE patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the volunteers for participating in our study and Gisella Cabiddu for the help with data acquisition. We are grateful for the two anonymous reviewers for the insightful advice provided on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the study.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2013.07.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Supplementary material.

References

- Adcock J.E., Wise R.G., Oxbury J.M., Oxbury S.M., Matthews P.M. Quantitative fMRI assessment of the differences in lateralization of language-related brain activation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. NeuroImage. 2003;18:423–438. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora J., Pugh K., Westerveld M., Spencer S., Spencer D.D., Todd Constable R. Language lateralization in epilepsy patients: fMRI validated with the Wada procedure. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2225–2241. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo J.V., Arévalo A., Patterson J.P., Dronkers N.F. Grey and white matter correlates of picture naming: evidence from a voxel-based lesion analysis of the Boston Naming test. Cortex. 2012;49:658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berl M.M., Balsamo L.M., Xu B., Moore E.N., Weinstein S.L., Conry J.A. Seizure focus affects regional language networks assessed by fMRI. Neurology. 2005;65:1604–1611. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184502.06647.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder J.R., Sabsevitz D.S., Swanson S.J., Hammeke T.A., Raghavan M., Mueller W.M. Use of preoperative functional MRI to predict verbal memory decline after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1377–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder J.R., Desai R.H., Graves W.W., Conant L.L. Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:2767–2796. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder J.R., Gross W.L., Allendorfer J.B., Bonilha L., Chapin J., Edwards J.C. Mapping anterior temporal lobe language areas with fMRI: a multicenter normative study. NeuroImage. 2011;54:1465–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binney R.J., Embleton K.V., Jefferies E., Parker G.J., Ralph M.A. The ventral and inferolateral aspects of the anterior temporal lobe are crucial in semantic memory: evidence from a novel direct comparison of distortion-corrected fMRI, rTMS, and semantic dementia. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20:2728–2738. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquillon P., Dujardin K., Betrouni N., Phalempin V., Houdayer E., Bourriez J.L., Derambure P., Szurhaj W. Attention impairment in temporal lobe epilepsy: a neurophysiological approach via analysis of the P300 wave. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:2267–2277. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli S.B., Powell R.H., Yogarajah M., Samson R.S., Symms M.R., Thompson P.J., Koepp M.J., Duncan J.S. Imaging memory in temporal lobe epilepsy: predicting the effects of temporal lobe resection. Brain. 2010;133:1186–1199. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli S.B., Powell R., Thompson P.J., Yogarajah M., Focke N.K., Stretton J. Hippocampal activation correlates with visual confrontation naming: fMRI findings in controls and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2011;95:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli S.B., Thompson P.J., Yogarajah M., Vollmar C., Powell R.H., Symms M.R. Imaging language networks before and after anterior temporal lobe resection: results of a longitudinal fMRI study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:639–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.M., Morris G.L., Drea L.A., Kroll J.L. Unexpected right hemisphere language representation identified by the intracarotid amobarbital procedure in right-handed epilepsy surgery candidates. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2008;13:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K.G., Bell B.D., Bush A.J., Hermann B.P., Dohan F.C., Jr., Jaap A.S. Naming decline after left anterior temporal lobectomy correlates with pathological status of rested hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1998;39:407–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere K., Boon P.A., Vandemaele P. MRI language dominance assessment in epilepsy patients at 1.0 T: region of interest analysis and comparison with intracarotid amytal testing. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00234-004-1196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dym R.J., Burns J., Freeman K., Lipton M.L. Is functional MR imaging assessment of hemispheric language dominance as good as the Wada test?: a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2011;261:446–455. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr., Van Ness P.C., Rasmussen T.B. In: Surgical Treatment of Epilepsies. Engel J., editor. Raven Press; New York: 1993. Outcome with respect to epileptic seizures; pp. 609–621. [Google Scholar]

- Gabr M., Lüders H., Dinner D., Morris H., Wyllie E. Speech manifestations in lateralization of temporal lobe seizures. Annals of Neurology. 1989;25:82–87. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard W.D., Balsamo L., Xu B., McKinney C., Papero P.H., Weinstein S. fMRI language task panel improves determination of language dominance. Neurology. 2004;63:1403–1408. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141852.65175.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli A.R., Erbetta A., Villani F., Avanzini G. Semantic memory in partial epilepsy: verbal and non-verbal deficits and neuroanatomical relationships. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:1482–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger M.J., Seidel W.T., Goodman R.R., Williams A., Perrine K., Devinsky O. Evidence for cortical reorganization of language in patients with hippocampal sclerosis. Brain. 2007;130:2942–2950. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C., Kurthen M., Linke D.B., Elger C.E. Patterns of language dominance in focal left and right hemisphere epilepsies: relation to MRI findings, EEG, sex, and age at onset of epilepsy. Brain and Cognition. 1997;33:135–150. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1997.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C., Kurthen M., Lux S., Reuber M., Elger C.E. Chronic epilepsy and cognition: a longitudinal study in temporal lobe epilepsy. Annals of Neurology. 2003;54:425–432. doi: 10.1002/ana.10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G., Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janszky J., Jokeit H., Heinemann D., Schulz R., Woermann F.G., Ebner A. Epileptic activity influences the speech organization in medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2003;126:2043–2051. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E., Goodglass H., Weintraub S. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. Boston Naming Test. [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel S., Büchel C. Alternatives to the Wada test: a critical view of functional magnetic resonance imaging in preoperative use. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2005;18:418–423. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000170242.63948.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner M., Laxer K.D. Ictal speech, postictal language dysfunction, and seizure lateralization. Neurology. 1988;38:634–636. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambon Ralph M.A., Ehsan S., Baker G.A., Rogers T.T. Semantic memory is impaired in patients with unilateral anterior temporal lobe resection for temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2012;135:242–258. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfitt J.T., Rausch R. Word-finding deficits persist after left anterotemporal lobectomy. Archives of Neurology. 1996;53:72–76. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550010090021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehéricy S., Cohen L., Bazin B., Samson S., Giacomini E., Rougetet R. Functional MR evaluation of temporal and frontal language dominance compared with the Wada test. Neurology. 2000;54:1625–1633. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccotta L., Buckner R.L., Gilliam F.G., Ojemann J.G. Changing frontal contributions to memory before and after medial temporal lobectomy. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:443–456. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messas C.S., Mansur L.L., Castro L.H. Semantic memory impairment in temporal lobe epilepsy associated with hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2008;12:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.10.014. (Feb) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noppeney U., Price C.J., Duncan J.S., Koepp M.J. Reading skills after left anterior temporal lobe resection\: an fMRI study. Brain. 2005;128:1377–1385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli G., Papagno C., Capitani E., Laiacona M., Cappa S.F., Vallar G. Tre test clinici di ricerca e produzione lessicale. Taratura su soggetti normali. Archivio di Psicologia Neurologia Psichiatria. 1986;47:477–506. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell H.W., Parker G.J., Alexander D.C., Symms M.R., Boulby P.A., Wheeler-Kingshott C.A. Abnormalities of language networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. NeuroImage. 2007;36:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera M., Kim K.K. Postictal language function. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera M., Kohler C., Cahill W., Yeh H.S. Postictal language dysfunction in patients with right or bilateral hemispheric language localization. Epilepsia. 1996;37:936–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M.J., Schefft B.K., Howe S.R., Hwa-Shain Y., Privitera M.D. Interictal and postictal language testing accurately lateralizes language dominant temporal lobe complex partial seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:22–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch R., Kraemer S., Pietras C.J., Le M., Vickrey B.G., Passaro E.A. Early and late cognitive changes following temporal lobe surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;60:951–959. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000048203.23766.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosazza C., Minati L., Ghielmetti F., Maccagnano E., Erbetta A., Villani F. Engagement of the medial temporal lobe in verbal and nonverbal memory: assessment with functional MR imaging in healthy subjects. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2009;30:1134–1141. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten G.J., Ramsey N.F., van Rijen P.C., Alpherts W.C., van Veelen C.W. FMRI determined language lateralization in patients with unilateral or mixed language dominance according to the Wada test. NeuroImage. 2002;17:447–460. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabsevitz D.S., Swanson S.J., Hammeke T.A., Spanaki M.V., Possing E.T., Morris G.L. Use of preoperative functional neuroimaging to predict language deficits from epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2003;60:1788–1792. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068022.05644.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz M., Pauli E. Postoperative speech processing in temporal lobe epilepsy: functional relationship between object naming, semantics and phonology. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2009;16:629–633. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer J.A., Binder J.R., Hammeke T.A. Language dominance in neurologically normal and epilepsy subjects: a functional MRI study. Brain. 1999;122:2033–2046. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafiniak P., Saykin A.J., Sperling M.R., Kester D.B., Robinson L.J., O'Connor M.J., Gur R.C. Acute naming deficits following dominant temporal lobectomy: prediction by age at 1st risk for seizures. Neurology. 1990;40:1509–1512. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.10.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella F., Maciel J.A. Attentional disorders in patients with complex partial epilepsy. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2003;61:335–338. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2003000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassi L., Meroni A., Deleo F., Villani F., Mai R., Russo G.L. Temporal lobe epilepsy: neuropathological and clinical correlations in 243 surgically treated patients. Epileptic Disorders. 2009;11:281–292. doi: 10.1684/epd.2009.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivard L., Hombrouck J., du Montcel S.T., Delmaire C., Cohen L., Samson S. Productive and perceptive language reorganization in temporal lobe epilepsy. NeuroImage. 2005;24:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasino B., Marin D., Maieron M., Ius T., Budai R., Fabbro F., Skrap M. Foreign accent syndrome: a multimodal mapping study. Cortex. 2011;49:18–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebuchon-Da Fonsa A., Guedj E., Alario F.X., Laguitton V., Mundler O., Chauvel P., Liegeois-Chauvel C. Brain regions underlying word finding difficulties in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2009;132:2772–2784. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N., Landeau B., Papathanassiou D. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali P., Dronkers N., Pincherle A., Giovagnoli A.R., Marras C., D'Incerti L. Accuracy of pre-surgical fMRI confirmed by subsequent crossed aphasia. Neurological Science. 2011;32:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0426-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada J., Rasmussen T. Intracarotid injection of sodium amytal for the lateralization of cerebral speech dominance Experimental and clinical observations. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1960;17:266–282. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B., Wellmer J., Reuber M., Mormann F., Weis S., Urbach H., Ruhlmann J., Elger C.E., Fernández G. Left hippocampal pathology is associated with atypical language lateralization in patients with focal epilepsy. Brain. 2006;129:346–351. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]