Abstract

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are a series of 8 goals and 18 targets aimed at ending extreme poverty by 2015, and there are 48 quantifiable indicators for monitoring the process. Most of the MDGs are health or health-related goals. Though the MDGs might sound ambitious, it is imperative that the world, and sub-Saharan Africa in particular, wake up to the persistent and unacceptably high rates of extreme poverty that populations live in, and find lasting solutions to age-old problems. Extreme poverty is a cause and consequence of low income, food insecurity and hunger, education and gender inequities, high disease burden, environmental degradation, insecure shelter, and lack of access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation. It is also directly linked to unsound governance and inequitable distribution of public wealth. While many regions in the world will strive to attain the MDGs by 2015, most of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with major human development challenges associated with socio-economic disparities, will not. Zambia’s MDG progress reports of 2003 and 2005 show that despite laudable political commitment and some advances made towards achieving universal primary education, gender equality, improvement of child health and management of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, it is not likely that Zambia will achieve even half of the goals. Zambia’s systems have been weakened by high disease burden and excess mortality, natural and man-made environmental threats and some negative effects of globalization such as huge external debt, low world prices for commodities and the human resource “brain drain”, among others. Urgent action must follow political will, and some tried and tested strategies or “quick wins” that have been proven to produce high positive impact in the short term, need to be rapidly embarked upon by Zambia and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa if they are to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

Keywords: Millennium Development Goals, health, extreme poverty, inequity, “quick wins”

Introduction

The Constitution of the World Health Organization states: “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being, without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition” [1]. It also defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”, and has as objective “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health” [1]. These broad statements suggest that health and ill health are dependent on a large number of factors, several of which are not in the health sector at all. Political, social, economic and environmental factors all determine health outcomes. However, the complex and multi-dimensional phenomenon of poverty is said to be the factor most strongly associated with ill health and premature death. Poverty is both the cause and the consequence of ill health: the low income of the poor cannot provide for adequate quantities of nutritious food and this low intake in turn leads to weakened, malnourished bodies incapable of adequate mental and physical productivity, and incapable of fighting off disease. For ease of comparison worldwide, poverty has been defined as the inability to afford US$1 for daily consumption per person [2]. Cognizant of the causes and consequences of poverty, the member states of the United Nations, meeting at the Millennium Summit held in 2000, signed the Millennium Declaration, a far-reaching document that was meant to chart the way for eradicating extreme poverty and for making the world a better place to live in by 2015 [3]. The Declaration was a pledge that outlined 8 broad goals (the Millennium Development Goals or MDGs) and set 18 targets to be monitored using 48 proposed quantifiable indicators. Although the goals are broad, some of the targets are quite ambitious, especially since the different regions of the world were at different stages of socio-economic development when the goals and targets were set. The following are the 8 MDGs: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; develop a global partnership for development. The goals will compare the 2015 deadline target values with those of 1990. Extreme poverty has been defined as “poverty that kills, by depriving people of the means to stay alive in the face of hunger, disease and environmental hazards” [3].

Health is at the core of the MDGs. It is widely accepted that although only three of the MDGs (Goals 4, 5 and 6) are health goals, the rest of them, as well as 8 of the 18 targets, and 18 of the 48 indicators are health-related. The significance of the MDGs lies in the linkages between the goals: they are a mutually-reinforcing framework to improve overall human development.

All the health and health-related MDGs could be successfully achieved largely by ensuring equitable and rights-based provision of appropriate, adequate, accessible and affordable nutrition, health information, health care, shelter, water and sanitation to the majority of the population. However, health inequalities (the differences or variations in the health-related quality of life) and inequities (the unfairness or unjustness in the distribution of differences) prevalent in the developing world, coupled with the devastating health consequences associated with environmental degradation from human activities, are impeding the attainment of the MDGs. Preliminary country reports world-wide indicate that developing countries might not achieve most of the MDGs. Zambia’s case study should highlight the difficulties and constraints that developing countries are facing in trying to achieve these universal goals.

Materials and Methods

The period between 2002 and 2003 was the mid point of the time interval covered by the MDG targets (1990 to 2015). Interim reports on the level of attainment of the MDGs in the different regions of the world have been briefly examined and that of Zambia described in greater detail. Comparisons have been made regarding whether or not a target has been met, or is on track, whether there is progress but slow, whether there is no progress or no change in the target, and if there are no data available. An attempt has then been made to link the shortcomings to various health inequities and to environmental insecurity. Finally, suggestions have been made on evidence-based quick wins that would greatly increase countries’ chances of achieving the Millennium Development Goals.

Results

Attainment of MDGs in the Different Regions of the World

In general, most regions of the world are progressing favourably with regards to meeting the targets of most of the goals [3–5]. Table 1 gives a summary of the trends in the attainment of the targets of the MDGs in some regions. These regions are Africa (sub-divided into Northern and sub-Saharan Africa), Asia (sub-divided into Eastern, South-eastern, Southern and Western), Oceania, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Commonwealth of Independent States, formerly the Russian Republics (subdivided into states in Europe and those in Asia). Results show that of all the regions reviewed, the sub-Saharan region is the only one that has not met any, or is on track to meeting any of the goals, as of 2004. The best trends in sub-Saharan Africa so far are associated with progress being made in achieving universal primary education (Goal 2), in promoting gender equality and empowering women (Goal 3), and in improving the proportion of people with access to safe drinking water in rural areas (Goal 7). However, the region is still lagging behind all the others, even in the attainment of these goals. Another promising trend in sub-Saharan Africa is the overall stability in the number of new HIV/AIDS cases, and this is the one goal in which the region seems to be doing better than some other regions.

Table 1.

Major trends in the attainment of the MDGs, by region, 2004

| Africa 840 million | Asia 3,738 million | Oceania | Latin America and the Caribbean | Commonwealth of Independent states 281 million | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| North | Sub Saharan | East | South East | Southern | Western | Europe | Asia | |||

| Goal 1: Eradicate Extreme Hunger | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Reduce poverty by half | On track | High no change | Met | On track | On track | Increase | ····· | Low minimal improvement | Increase | Increase |

| Reduce hunger by half | On track | Very high no change | On track | On track | Progress but lagging | Increase | Moderate no change | On track | Low, no change | Increase |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 2: Achieve Universal Primary Education | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Universal primary schooling | On track | Progress but lagging | Met | Lagging | Progress but lagging | High but no change | Progress but lagging | On track | Decline | On track |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 3: Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Equal girls enrollment in primary schools | On track | Progress but lagging | Met | On track | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | On track | On track | Met | On track |

| Equal girls enrollment in secondary school | Met | No significant change | ····· | Met | No significant change | No significant change | Progress but lagging | On track | Met | Met |

| Literacy parity between young women and men | Lagging | Lagging | Met | Met | Lagging | Lagging | Lagging | Met | Met | Met |

| Women’s equal representation in national parliaments | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | Decline | Progress but lagging | Very low, small progress | Very low, no change | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | Recent progress | Decline |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Reduce mortality of under five years olds by two thirds | On track | Very high, no change | Progress but lagging | On track | Progress but lagging | Moderate, no change | Moderate no change | On track | Low no change | Increased mortality |

| Measles immunization | Met | Low no change | Progress but lagging | On track | Progress but lagging | On track | Decline | Met | Met | Met |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 5: Improve Maternal Health | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Reduce maternal mortality by three quarters | Moderate level | Very high level | Low level | High level | Very high level | Moderate level | High level | Moderate level | Low | Low |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other Diseases | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Halt and reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS | ····· | Stable | Increase | Stable | Increase | ····· | Increase | Stable | Increase | Increase |

| Halt and reverse the spread of malaria | Low risk | High risk | moderate risk | moderate risk | moderate risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Hal and reverse the spread of TB | Low risk | High increasing | Moderate declining | High declining | High declining | Low declining | High increasing | Low declining | Moderate increasing | Moderate increasing |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 8: Global Partnership For Development | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Youth unemployment | High no change | High no change | Low increasing | Rapidly increasing | Low increasing | High increasing | Low increasing | Increasing | Low, rapidly increasing | Low, rapidly increasing |

|

| ||||||||||

| Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Reverse loss of forests | Less than 1% of forests | Decline | Met | Decline | Small decline | Less than 1% forest | Decline | Decline except Caribbean | Met | Met |

| Half the proportion without improved drinking water in urban areas | High access but little change | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | On track | Progress but lagging | Low access no change | Progress but lagging | High access but limited change | High access but limited change |

| Half the proportion without sanitation in urban areas | On track | Low access no change | Progress but lagging | On track | On track | Met | High access but no change | High access but no change | High access but no change | High access but no change |

| Half proportion without sanitation in rural areas | Progress but lagging | No significant change | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | Progress but lagging | No significant change | No significant change | Progress but lagging | No significant change | No significant change |

| Improve the lives of slum dwellers | On track | Rising number and proportion of slum dwellers | Progress but lagging | On track | Some progress | Rising number and proportion of slum dwellers | ····· | Progress but lagging | Low but no change | Low but no change |

Source: Millennium Development Goals, 2004. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/mdg2004

Attainment of MDGs in Zambia: Progress Report

Zambia is a landlocked sub-Saharan country lying between 8º and 18º South (latitude) and 22º and 34º East (longitude). It covers a land area of 752,612 square kilometres and about 58% of its total land area is classified as having medium to high potential for agricultural production [8]. The 2005 population estimate is 11.4 million inhabitants, with 67% of the population below 15 years of age. At independence in 1964 and in the decade after, Zambia was one of the most prosperous countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with its wealth largely based on copper exports. Since the crash of copper prices in 1975, Zambia has slowly become one of the poorest and most heavily indebted countries in Africa [8, 9]. On reaching the completion point of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative of the international financial institutions in March 2005, Zambia has had its external debt written off by the G8 industrialized countries. However, internal debt remains extremely high and poverty levels are increasing for a variety of reasons.

The level of attainment of the MDGs has been monitored twice in Zambia, in 2003 and in 2005, and the 2005 draft report shows progress being made over the years. The trends in the reports are based on the data of 2000 and 2005 respectively, with 1990 as the baseline. Table 2 gives a synopsis of the main socio-economic indicators in Zambia. Thereafter, the level of attainment of each health-related MDG is presented in subsequent tables and figures.

Table 2.

Key Socio-Economic Indicators of Zambia

| Indicator | Value | Year | Latest Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population size (million) | 9.9 | 2000 | 11.4m (2005)* |

| Annual population growth rate (%) | 2.5 | 2000 | |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 50 | 2000 | 37.5 (2005) |

| Real GDP per capita (US$) | 354 | 2002 | 877 (2005) |

| Domestic debt as % of GDP | 26 | 2002 | |

| External debt as % of GDP | 190 | 2002 | |

| Debt service as % of exports of goods and services | 13.7 | 2002 | |

| Human development Index (value) | 0.38 | 2003 | |

| Human Development Index (rank out of 175) | 163 | 2003 | 166 (2005) |

| Population below national poverty line (%) | 73 | 1998 | 63.7 (2005) |

| Prevalence of HIV/AIDS (15–49 years) | 16 | 2002 | |

| Percentage of underweight children under 5 years (%) | 28 | 2002 | |

| Infant mortality (per 1,000 live births) | 95 | 2002 | |

| Under five mortality (1,000 live births) | 168 | 2002 | |

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000 live births) | 729 | 2002 | |

| Adult literacy (%) | 67 | 2000 | |

| Net enrolment in primary education (%) | 72 | 2002 | |

| Population without access to safe drinking water supply (%) | 51 | 2002 | |

| Population relying on traditional fuels for energy use (%) | 83 | 2000 |

Source: Zambia MDG report 2003:

Estimate

The 2005 projection of the total population is about 11.4 million inhabitants, and the life expectancy at birth is said to have dropped to below 40 years [9]. Zambia is a Highly Indebted Poor Country and has just had its foreign debt written off in June 2005. The proportion of the national budget allocated for health in 2005 is 11.8%, short of the 15% target agreed upon by all African Heads of State in Abuja in 2000.

Table 3 provides four levels of answers to questions concerning whether or not a target of a goal will be met (“likely”, “probably”, “potentially” or “unlikely”), and whether or not there is adequate national support for meeting the target (“strong”, “good”, “weak but improving” or “weak”). At a glance, there are more targets in 2005 that will likely be met or have the potential of being met, than there were in 2003. The most likely targets to be met are universal primary education, gender equality and women empowerment, and HIV/AIDS halting or reversal. Those that are unlikely to be met by 2015 are reduction of hunger, maternal mortality ratio and HIV/AIDS. National support (or political will) is strongest for the promotion of universal primary education and reduction of child mortality, but weakest in the reduction of hunger, reduction of maternal mortality, improvement of environmental sustainability and provision of water and sanitation.

Table 3.

MDG Progress report in Zambia: Status at a Glance

| Zambia’s Progress towards the Millennium Development Goals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals/Targets | Will target be met? | State of national support | ||

| 2005 | 2003 | 2005 | 2003 | |

|

Extreme Poverty Halve between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty. |

Potentially | Unlikely | Good | weak but improving |

|

Hunger Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger |

Unlikely | Unlikely | Weak | weak but improving |

|

Universal Primary Education Ensure that by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling |

Likely | Potentially | Strong | Strong |

|

Gender Equality and Women Empowerment Eliminate gender disparity in Primary and Secondary Education preferably by 2005 and to all levels of education no later than 2015 |

Likely | Probably | Good | Fair |

|

Child Mortality Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under five mortality rate |

Potentially | Potentially | Strong | Fair |

|

Maternal Mortality Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio |

Unlikely | Unlikely | Weak | weak but improving |

|

HIV/AIDS Have halted by 2015, and began to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS |

Likely | Potentially | Good | Fair |

|

Malaria and other major diseases Have halted by 2015, and began reversing the incidence of malaria and other major diseases |

Potentially | Potentially | Good | Fair |

|

Environmental Sustainability Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes and reverse the loss of environmental resources |

Unlikely | Unlikely | Weak | weak but improving |

|

Water and Sanitation Halve by 2015 the proportion without sustainable access to safe drinking water and sanitation. |

Potentially | Potentially | Weak | weak but improving |

Source: Zambia MDGs draft status reports 2003 and 2005

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Target 1: Reduce by half, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty

Although the proportion of the total population living in extreme poverty is slowly decreasing, extreme poverty in urban areas has more than doubled between 1990 and 2003. Extreme poverty seems be on the decrease in rural areas mainly because of the mass internal migration of the population from the rural to the urban areas, where most of those from the rural areas are skill-less, jobless, and live in spontaneous housing settlements with neither water nor sanitation.

Target 2 – Reduce by half, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

The indicator used for monitoring target 2 is the proportion of underweight children below the age of 5 years. Stunting denotes chronic under-nourishment while wasting denotes more acute under-nourishment. Table 5 shows that the level of chronic malnutrition in Zambian children has worsened since 1990 (40% to 47%), and this type of malnutrition is more difficult to correct.

Table 5.

Trends in proportion of underweight children under five in Zambia

| Indicator | 1990 | 2001/2 | 2015 MDG target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight children <5 years of age (%) | 25 | 28 | 12.5 |

| Stunted children <5years of age (%) | 40 | 47 | 20.0 |

| Wasted children <5 years of age (%) | 5 | 5 | 2.5 |

Source: Zambia MDGs report, 2003; LCMS, 2004

Goal 4: Reduce child mortality

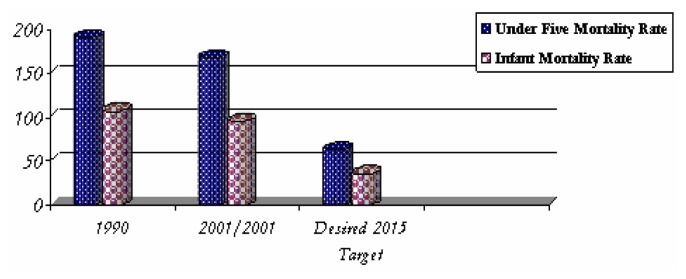

Target 5: Reduce by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate

The indicators for monitoring this target are infant and child (under five) mortality rates, as well as the proportion of one year old children immunized against measles.

Child (under-five) and infant (under-one) mortality rates have steadily improved over time. Intermittent supplemental measles immunization campaigns, heavily subsidized by donor partners and development agencies, have markedly improved measles coverage rates and drastically reduced measles-associated childhood deaths.

Table 6 and figure 1 show that both infant and underfive mortality rates in Zambia are getting better over the years, thanks to aggressive and sustained routine and supplemental childhood immunization programmers. The figure vividly demonstrates the marked reduction in measles-related deaths.

Table 6.

Trends in infant and child mortality indicators in Zambia

| Indicator | 1990 | 2001/2 | 2015 MDG target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-five mortality rate/1000 live births | 191 | 168 | 63* |

| Infant mortality rate/1000 live births | 107 | 95 | 35* |

| Proportion of 1 year-old children immunized against measles | No data | 99% | 99%** |

Source: ZDHS, 2001–2002

Central Board of Health HMIS data base 2005

Figure 1.

Trends in Infant and Child Mortality. Source: ZDHS 2001–2002.

Goal 5: Improve maternal health

Target 6: Reduce by three-quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio

Maternal health indicators are maternal mortality ratio and the proportion of deliveries attended by a skilled health care worker (nurse, midwife, clinical officer or doctor).

Maternal deaths have been on the increase since 1990 and Zambia now has one of the highest maternal mortality ratios in the sub-continent. Maternal deaths occur because of the “three delays”: delay in deciding when to seek medical attention; delay in getting to the health care facility; delay in getting the appropriate service required, including referral to a higher-level facility.

For both of the indicators used in assessing maternal health in Zambia, the trend has been a systematic worsening over the years (table 7, figure 2). In 1992, more than 50% of all deliveries took place in a health facility and was attended by trained medical staff. In 2002, only about 43% of deliveries were attended by a skilled health worker. Some reasons for pregnant women not going to health facilities to deliver include distance from the health facility, lack of financial resources for transportation and for payment for medical services rendered, as well as the unavailability of trained health care workers at the health facilities. As fewer deliveries take place in health facilities, and with fewer deliveries being carried out by a skilled health worker, it is not surprising that maternal mortality ratio is getting worse.

Table 7.

Trends in maternal mortality indicators in Zambia

| Indicator | 1990 | 2001/2 | 2015 MDG target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality ratio/100,000 live births | 649 | 729 | 162 |

| Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel | 51% | 43% | 80% |

Source ZDHS 2001–2002

Figure 2.

Trends in Assisted Deliveries and Deliveries in Health Facilities 1992–2002. Source: ZDHS 2001–2002.

Table 8 summarizes the health care worker dilemma which Zambia faces. The national average for medical doctor to population ratio is 1:17,589, but Lusaka province, in which the capital city of Lusaka is located, has the greatest number of all doctors, with a ratio of 1:6,247. Lusaka also has the greatest concentration of all cadres of health personnel. Copperbelt province, the only other urbanized province of the nine provinces in Zambia, also has better ratios than the seven rural provinces which have really catastrophic ratios of health worker to population. The national ratios for all cadres of health personnel to population are distressing across the board, and cannot possibly provide for adequate health services. Pharmacy and laboratory technicians are those in shortest supply. The strenuous demands on the health system for clinical and laboratory diagnosis, treatment and care for HIV/AIDS sufferers cannot be met with the levels of skilled human resources presently available. The additional national catastrophe of the “brain drain” of skilled health workers from Zambia to better endowed countries in the southern African sub-region, but especially to Britain, the USA and Canada, has almost completely ruined the service delivery in the public health system. The “brain drain” also depletes the number of tutors in health training institutions, further reducing the numbers of health workers being trained to replenish those lost to migration, retirement and death. It is little wonder therefore that the maternal mortality ratio in Zambia is one of the highest in the world, given the paucity of midwives in the rural areas.

Table 8.

Ratio of trained medical human resources to population, for urban provinces (Copperbelt & Lusaka), rural provinces (averages for 7 provinces) and for total population of Zambia, 2005

| Province | Dr:Pop | CO:Pop | RM:Pop | RN:Pop | ZEM:Pop | ZEN:Pop | Pharm. Staff:Pop | Lab. Staff:Pop | EHT:Pop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lusaka | 6,247 | 7, 544 | 12, 397 | 3,799 | 5, 243 | 1,577 | 319,847 | 15,527 | 27,573 |

| Copperbelt | 8,998 | 9, 719 | 14, 425 | 5, 091 | 3, 599 | 1,567 | 55,076 | 16,523 | 23,006 |

| Average Rural | 43,313 | 10,970 | 74, 713 | 17, 324 | 11, 541 | 2,863 | 169,160 | 49,582 | 13,099 |

| Provinces National | 17,589 | 9, 787 | 27, 714 | 8, 822 | 6, 099 | 2,293 | 123,509 | 27,249 | 15,150 |

Sources: Ministry of Health 2005 (Verbal Communication)

Dr = Medical Doctor; CO = Clinical Officer; RM = Registered Midwife RN = Registered Nurse; ZEM = Zambia Enrolled Midwife; ZEN = Zambia Enrolled Nurse; EHT = Environmental Health Technician

Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

Target 7: Have halted by 2015, and began to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

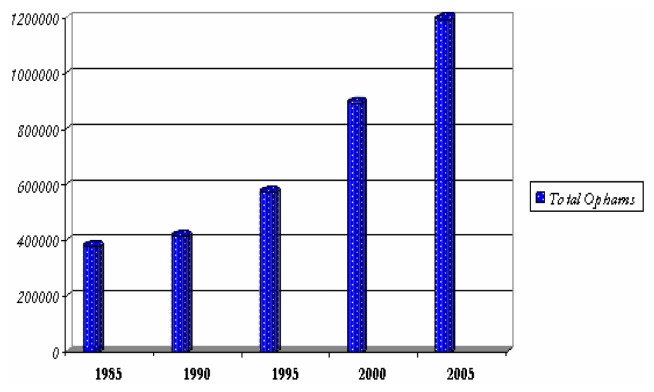

There are three indicators for this target, namely HIV prevalence rate among 15–24 year old pregnant women, rate of condom use and number of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. The Zambia Demographic and Health Survey of 2001–2002 [7] found the average HIV prevalence rate in persons aged 15–49 years to be 16%, with females having a higher prevalence rate (18%) than males (13%), both in urban and in rural areas. Overall prevalence in the urban areas is higher (25%) than in rural areas (13%). Epidemiological sentinel surveillance of pregnant women aged 15–24 years indicated that the HIV prevalence rate in this age group was 19%. Figure 3 shows the prevalence rates by sex and by residence. Males and females in urban areas are using slightly more condoms with non-regular sexual partners than men and women living in rural areas [9–11], and figure 4 shows the differences observed. The number of orphaned children has risen dramatically since 1995 (figure 5) and the latest estimates suggest that there are about one million orphans in Zambia. Between half and two thirds of them are children orphaned by HIV/AIDS [10, 11]. Many of these orphans are also HIV positive and till now have seldom had access to anti-retroviral therapy. However, Zambia subscribed to the UN’s “3 by 5” initiative for scaling up treatment of HIV-positive persons who qualify, and was providing antiretroviral treatment (ART) on a fee-for-service basis. In July 2005, Government declared that ART would be free for all who qualify.

Figure 3.

HIV prevalence rate by sex and by residence (urban/rural). Source: ZDHS 2001–2002

Figure 4.

Condom Use with Non Regular Sexual Partner during Most Recent Sexual Act. Source: Joint Review of the national HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Intervention Strategic Plan 2002–2005

Figure 5.

Total Number of Orphaned children in Zambia: 1985–2005. Source: Joint Review of the national HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Intervention Strategic Plan 2002–2005

There is very little change in the proportion of males and females in both urban and rural areas regarding the use of a condom with a non-regular sexual partner. It would even seem that rural males and females used less condoms in 2003 compared to 2000. It is therefore clear that risky sexual behaviour is still prevalent, although this might be due to the high poverty level and the lack of financial resources to buy anything, condoms included.

The number of orphaned children has risen dramatically since 1995 and the latest estimates suggest that there are over one million orphans in Zambia and between half and two thirds of them are children orphaned by HIV/AIDS [10, 11]. Many of these orphans are also HIV positive and seldom have access to anti -retroviral therapy. With the death of parents and grandparents, the traditional custodians of orphans, and with the severe poverty levels that prevail, the extended family system is breaking down and more and more orphans are becoming street children, with no fixed abode. Female orphans frequently engage in sex work to survive.

Target 8: To halt and begin to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases by 2015

The four indicators for this target include prevalence and death rates associated with malaria, proportion of population at risk of malaria that use effective malaria prevention and treatment measures, and prevalence and death rates associated with tuberculosis.

Malaria continues to be the leading cause of ill health and presently accounts for 47% of the overall disease burden in Zambia, especially prevalent in pregnant women and children under 5 years of age [12]. It is also continuously among the top five causes of death over the years, accounting for 50,000 deaths each year, and for 20% of maternal mortality. The second leading cause of ill health is tuberculosis, classified as non-pneumonia respiratory infection, and it now known that about 60% of all the TB cases in Zambia are HIV-positive [9,10]. In 2004, the leading causes of death were AIDS-related (pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, diarrhoea and TB), followed by malaria which would have been the leading cause of death in the absence of AIDS. Malaria is still the leading cause of death in children in Zambia and its overall fatality rate is increasing (Table 10).

Table 10.

Trends in malaria indicators in Zambia

| Indicator | 1990 | 2002 | 2015 MDG target |

|---|---|---|---|

| New malaria cases per 1000 | 255 | 377 | Less than 121 |

| Malaria fatality rates per 1000 | 11 | 48 | |

| Households with ITN* (%) | - | 14 |

Source: Zambia Demographic and Health Survey, 2001–2002.

ITN: Insecticide –Treated bed Net

The numbers of new cases and the deaths from malaria have been increasing over the years. Although there are no accurate data on the total number of households that presently own and use insecticide treated bed nets (ITN), anecdotal evidence indicates that a lot of families, both in the urban and rural areas, are using ITNs. These are now distributed free of charge to pregnant women and children below the age of five, the most vulnerable age groups, during supplemental immunization days and during campaigns.

Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

Target 9: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmers and reverse the loss of environmental resources

Table 11 shows that Zambia’s forests have declined sharply since 2001 and this is mainly because of wood harvesting for fuel (mainly as charcoal), for timber and for agriculture and human habitation [12]. It is said that the rate of deforestation has progressed from about 300,000 hectares per annum to the presently reported 800,000 hectares per annum. It is feared that at this rate of deforestation, Zambia might have no forests left in the next two decades.

Table 11.

Trends in forest resources in Zambia, 1990–2003

| Indicator | 1990 | 1996 | 2001 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of land covered by forest | 59.8 (1992) | 59.1 | 59.6 | 45 |

Source: Zambia MDGs draft status report 2005

Target 10: Reduce by half by 2015 the proportion without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation

Provision of safe drinking water and basic sanitation for the population is one of the targets that will potentially be met. This is shown in the steady increase over the years of the proportion of rural households that have access to clean water and hygienic toilet systems. Unfortunately, the urban areas have not witnessed a similar increase and this is largely attributed to the mushrooming of spontaneous habitations in peri-urban areas, with neither water nor sanitation. The phenomenon of the “urban poor” is acute.

It is also important to note that the open pit copper mines in the Central and Copperbelt provinces of Zambia have contributed to some environmental contamination of ground water and food stuffs [14]. Samples of garden vegetables (Chinese cabbage, pumpkin leaves, green beans leaves, and cassava leaves) grown in the mining town of Kabwe, were found to contain relatively high lead, cadmium and zinc levels, exceeding the Codex Food safety thresholds. However, the sample size of the plants studied was too small to provide conclusive evidence that consumption of those vegetables would lead to significant levels of heavy metal toxicity. Nevertheless, the potential risk to the environment (soil, water and air) of the numerous open pit copper and other mines in Zambia cannot be over emphasized.

Discussion

Zambia’s MDG progress reports for 2003 and 2005 highlight major challenges faced by the country where 67% of the population is classified as “poor”, i.e. living on US$1 a day (74% in rural and 52% in urban areas), and 46%% classified as “extremely poor”, i.e. surviving on less than $1 a day [8]. As has been seen in the monitoring of the progress report indicators, most, if not all of the indicator attainment levels are worse off in rural than in urban areas. It is well known that the rural areas are less endowed with all those socio-economic factors and determinants that impact on health and well being. These include well-staffed schools, well-equipped and well-staffed health care facilities, electricity, potable water, roads, adequate transportation and communication facilities, and food. The non-availability or inadequacy of these services is the greatest contributor to the inequities seen in the attainment of the health-related MDGs. Zambia is challenged by the “triple jeopardy” of high HIV sero-prevalence, food insecurity (alternate years of drought and floods, but also untapped agricultural potential) and weakened capacity for governance due mainly to the gross insufficiency of human resources nation-wide, but much worse in the rural areas, to high disease burden and excess mortality and to the negative effects of globalization. Harmful traditional beliefs and practices with regards to health, nutrition, agriculture, education and environmental management are compounding the problem.

In order for Zambia to convert the possibility of attainment of the MDGs from a pipe dream to a reality, there are opportunities to seize and best practices and “quick wins” to emulate. Opportunities such as the relatively calm political climate prevailing in the country, the strong political will and commitment to attain the MDGs, the availability of substantial donor funding for fighting HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, as well as for education and agriculture, the affluence of non-governmental organizations working in diverse areas of socio-economic development and the increasingly important emergence of public-private partnerships in solving the nation’s problems. Some of the “quick wins” that are known to work, as proposed in the U.N Millennium project report [3], are the following:

Allocate more funds to health, education and agriculture to ensure scaling up of all that works well to eradicate poverty.

Eliminate school and uniforms fees to enable all children, especially girls, attend and complete school.

Provide children with free school meals and take home rations, to prevent malnutrition and anaemia.

De-worm school children annually for improved health and educational outcomes.

Design community nutrition programmes that support breastfeeding and use of local indigenous foods as supplements.

In malaria-endemic areas, carry out combined activities such as distribution of free, insecticide-treated bed nets to children and pregnant women, intermittent preventive treatment of pregnant women, and indoor residual spraying.

Eliminate user fees (and all hidden costs) for basic health care.

Scale up treatment for AIDS, sexually transmitted infections, TB and malaria.

Scale up activities and messages for prevention of STIs and HIV.

Provide clean water, electricity, sanitation for all communities.

Provide farmers with affordable soil nutrients and technical skills for diversified farming and increased food production.

Train community leaders and members in health promotion, health, farming and infrastructure management so as to rapidly increase pool of skilled persons in rural communities.

Urgent action must follow political will and the above-listed activities that have been proven to produce high impact in the short term, need to be rapidly embarked upon, if Zambia is to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

Table 4.

Trends in proportion of population living in extreme poverty in Zambia

| Indicator | 1990 | 2003 | 2015 MDG target |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Total population living in extreme poverty | 58 | 46 | 29 |

| % Urban population living in extreme poverty | 32 | 74 | 16 |

| % Rural population living in extreme poverty | 81 | 52 | 40 |

LCMS, 2004

Table 9.

Top Five Causes of Morbidity and Mortality in Zambia, 1999–2004

| Disease | Incidence (Cases/1000 pop) | In-Patient CFR*(deaths/100 Admissions) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1999 | 2002 | 2004 | 1999 | 2002 | 2004 | |

| Malaria | 311.9 | 387.8 | 383.2 | 36.3 | 26.5 | 33.0 |

| Respiratory Infections: Non Pneumonia | 125.8 | 148.0 | 152.9 | 28.6 | 17.4 | 48.1 |

| Diarrhoea Non Bloody | 59.8 | 80.0 | 74.7 | 69.6 | 53.9 | 62.5 |

| Eye Infections | 38.8 | 42.7 | 39.7 | 17.8 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| Respiratory Infections: Pneumonia | 33.5 | 45.0 | 43.7 | 120.1 | 58.0 | 68.7 |

CFR= Case Fatality Ratio

Source: CBoH HMIS data base 2005

Table 12.

Trends in the indicators for safe drinking water and basic sanitation

| Percentage of households with access to an improved water source* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Indicator | 1991 | 1996 | 2000 | 2003 |

| All Zambia | 50 | 47 | 49.1..... | 53 |

| Rural | 20 | 28 | 31.2 (2001) | 37 |

| Urban | 90 | 85.3 | 89.8 (2001) | 86 |

|

| ||||

| Percentage of households with access to improved sanitation** | ||||

|

| ||||

| Indicator | 1991 | 1996 | 2000 | 2003 |

|

| ||||

| All Zambia | 24 | 18 | 14.9 | 65 |

| Rural | 6 | 2 | 2.9 (2001) | 57 |

| Urban | 47 | 45.9 | 44.8 (2001) | 80 |

Source: Zambia MDGs draft status report 2005

Data for 1991, 1996, and 2000 collected as “access to safe drinking water” which by definition is similar to 2003 on “access to an improved water source”

Data for 1991 1996, and 2000 collected as “access to sanitary means of excreta disposal” which is defined as access to flush toilet (whether private or communal) and ventilated pit latrines. This differs from the 2003 data on “improved sanitation” based on the UN (2003) definition which assumes that facilities such as a sewer or septic tank system, poor-flush latrines, simple pit or ventilated improved pit latrines are likely to be adequate, provided that they are not public or shared. Therefore, the 2003 data may not be comparable to that of the previous years.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Basic documents. WHO; Geneva: 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Poverty and health: a strategy for the African region (AFR/RC52/11) WHO; Brazzaville: 2003. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations. Millennium Development Goals. 2004. www.un.org/millenniumgoals/mdg2004.

- 4.U.N Millennium Project. Investing in development: a practical plan to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. UNDP; New York: 2005. pp. 1–95. Overview. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagstaff A., Claeson M. The Millennium Development Goals for Health: Rising to the challenges. Chapter 2. The World Bank; Washington D.C: 2004. pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans D., Edejer T. T. Choosing interventions that are cost effective: an aid to policy. African Health Monitor. 2005;5:227–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Health and the Millennium Development Goals. 2003. www.hlfhealthmdgs.org.

- 8.Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health and ORC Macro. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2001–2002. ORC Macro; Calverton: 2003. pp. 150–240. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Central Statistical Office. Living Conditions Monitoring Survey Report 2002/2003. GRZ; 2004. pp. 44–167. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health and MEASURE Evaluation. Zambia Sexual Behaviour Survey, 2003. Lusaka: 2004. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council. The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Zambia: Where are we now? Where are we going? Lusaka: 2004. pp. 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council. Joint Review of the national HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Intervention Strategic Plan 2002 2005. Lusaka: 2004. pp. 6–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health. Draft 5-year Strategic Plan: A road map for RBM impact in Zambia 2006–2010. Lusaka: 2005. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of the Republic of Zambia. Zambia Millennium Development Goals: status report 2003. GRZ; 2003. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Government of the Republic of Zambia. Zambia Millennium Development Goals: draft status report 2005. 2005:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copperbelt Environmental Project. Determination of the Extent of Contamination in the Vicinity of the Kabwe Mine; Kabwe Scoping Study Phase One Completion Report. Water management. ZCCM-IH Kitwe; 2004. [Google Scholar]