Abstract

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are significant public health threats. Although STEC O157 are recognized foodborne pathogens, non-O157 STEC are also important causes of human disease. We characterized 10 O157:H7 and 15 non-O157 clinical STEC derived from British Columbia (BC). Eae, hlyA, and stx were more frequently observed in STEC O157, and 80 and 100% of isolates possessed stx 1 and stx 2, respectively. In contrast, stx 1 and stx 2 occurred in 80 and 40% of non-O157 STEC, respectively. Comparative genomic fingerprinting (CGF) revealed three distinct clusters (C). STEC O157 was identified as lineage I (LI; LSPA-6 111111) and clustered as a single group (C1). The cdi gene previously observed only in LII was seen in two LI O157 isolates. CGF C2 strains consisted of diverse non-O157 STEC while C3 included only O103:H25, O118, and O165 serogroup isolates. With the exception of O121 and O165 isolates which were similar in virulence gene complement to STEC O157, C1 O157 STEC produced more Stx2 than non-O157 STEC. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) screening revealed resistance or reduced sensitivity in all strains, with higher levels occurring in non-O157 STEC. One STEC O157 isolate possessed a mobile bla CMY-2 gene transferrable across genre via conjugation.

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli are Gram negative, facultative anaerobic bacteria found in mammalian gastrointestinal tracts. Escherichia coli possessing Shiga toxin genes (stx) (i.e., Shiga toxin-producing E. coli [STEC]) pose serious health risks through consumption of contaminated food [1–4]. Classical enterohemorrhagic E. coli encode stx, plasmid pO157 (hlyA), and the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE); however, LEE negative strains may also cause severe disease [3], the most notable example being E. coli O104:H4 [5].

In 2003, Karmali et al. [6] grouped STEC into seropathotypes based on serogroup occurrence in human disease, the capacity to cause outbreaks, and the association with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). STEC O157:H7 and O157:NM were identified as the most significant public health risk (seropathotype A), whereas non-O157 STEC are progressively of lower risk from groups B to E. Recent estimates suggest that STEC O157 causes 50 to 70% of human infections, meaning that 30 to 50% are caused by non-O157 STEC [7–10]. A US study examining high-risk non-O157 STEC in beef revealed that 1006 of 4133 samples were positive for STEC by PCR, though only 10 isolates possessed virulence gene combinations of known pathogens [11]. Outside North America, non-O157 STEC are well-recognized sources of human illness [12–14]. In line with increasing concern for non-O157 STEC, the US Department of Agriculture has amended food safety regulatory policy, declaring STEC of O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, and O145 serogroups as beef adulterants [15].

Reports of hypervirulent clades or lineages of STEC O157 linked to human disease have been made. SNP analysis of 96 loci amongst 500 strains identified nine clades, including clade 8 linked with severe disease and designated hypervirulent [16]. Octamer-based genome scanning and length polymorphisms have identified three lineages (L) of O157; LI strains are represented in both cattle and human clinical isolates, and LII are predominantly from cattle [17–20]. Subsequent research examining Stx2 production showed differences across and within lineages. Sequencing of the stx 2 flanking region demonstrates that LII has the transcriptional activator gene Q of L1 strains replaced by a pphA homologue. Further, LI and LI/II strains produced more Stx2 than LII, and LI strains of human origin produced more Stx2 than bovine LI [21].

In British Columbia (BC), Canada, the rate of STEC infections have remained above the Canadian average since 2004, ranging between 2.4 and 4.3 cases/100,000 individuals [22]. However, no data exist describing the salient genetic features of STEC causing disease in BC or examined levels of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in clinical isolates. To this end, we examined clinical STEC originating from BC using molecular and phenotypic methods to examine lineage, stx subtype, toxin production, presence of other virulence loci and plasmids, and AMR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Selection and Serotyping

From the BCCDC Public Health Microbiology and Reference Laboratory Enteric Pathogen Monitoring Program during 2009-2010, we randomly selected 10 O157:H7 and 15 non-O157 STEC for genotypic and phenotypic characterization. All strains were propagated on Luria Bertani (LB) agar or broth (Becton Dickinson [BD], Mississauga, ON) and archived at −80°C in LB broth with 20% glycerol (Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON). Serotyping of all strains was performed using antisera from the Statens Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark).

2.2. Pulsed-Field Gel Electorphoresis

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns were used to compare the genetic relatedness of isolates belonging to the same serogroup. Whole-cell isolation of DNA for PFGE analysis was prepared according to standard procedures [23]. Briefly, DNA-containing agarose plugs were subjected to endonuclease restriction using XbaI. Resulting fragments were separated using a CHEF DR III system (BioRad, Hercules, California). In each run, Salmonella Branderup standards were included every four lanes. PFGE pattern analysis was performed using Bionumerics v.6.0 software using standard comparison criteria [24].

2.3. Plasmid Analysis

Plasmid was extracted (QIAprep Spin Miniprep; Qiagen, Toronto, ON) and 15 μL-electrophoresed using Tris-acetate EDTA (TAE) buffer (70 V, 4-5 h). Escherichia coli EDL933 was used as a control. Plasmid size markers included the BAC-Tracker Supercoiled DNA Ladder (Epicentre, Markham, ON) and the Supercoiled DNA Ladder (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON).

2.4. Virulence Typing

Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). Multiplex PCR was employed to detect the presence of stx 1, stx 2, eaeA, and hlyA [25]. All stx determinants were subtyped to identify stx 1, stx 1c, and stx 1d for stx 1 and stx 2, stx 2c, stx 2d, stx 2-O118, stx 2e, and stx 2g for stx 2 according to published methods [26, 27].

2.5. Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)

PCRs of 30 loci spanning the E. coli O157:H7 genome were used to fingerprint isolates as previously described [28]. Control strains included Sakai, ECI-272 and ECI-1717 for E. coli LI, I/II, and II, respectively, and K-12 (MG1655). Seven additional loci were used to increase genomic coverage and resolution (Table 1). For each locus, PCRs were repeated twice, with a positive result in either replicate being scored as presence (“1”) and a negative result in both replicates as absence (“0”).

Table 1.

The seven additional comparative genomic fingerprinting primers used in this study, their genomic location, and function of target region. The annealing temperature used for all primers was 55°C.

| Primer name | Forward sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse sequence (5′-3′) | O157:H7 strain: genome location (bp) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 | ACGGTTTCGCGCAGCTCCTCTT | GCCTGATGCGCACGGCATTCAA | EC4115: 2834437…2834633 | Phage replication initiation protein |

| B2 | GGTGCTCAAGCAGCGCCACAAA | TGCCGTTGCTTTGCCTGCCATT | EC4115: 1542851…1543021 | Putative capsid protein of prophage |

| C5 | TGGGAGGGTGCATGTAAGGCGT | TGGGGCATGAACTTGGGGGAGT | EC4115: 3295343…3295780 | Predicted excisionase |

| F1 | TCGCAGGTATGGGTGCTGCTGT | ACGACGAAGCTTACCCTGCTGC | EC4115: 5180205…5180308 | Hypothetical protein |

| E4 | TGCAAAGGCATGGGTCCCAACG | TGATGCGGCAGCTATGGTCGCA | Sakai: 2933058…2933350 | Transcriptional regulator, XRE family |

| E1 | AGTTCGCCAGTAGGCTTGCGCT | TTCGACGGGCAATTTCTGCCTGC | Sakai: 1929526…1929606 | Putative transcriptional regulator |

| C2 | AGGCATGCGACCTTTCTAACTGGCA | TCTTCAGCGGCTGCCTGATATGCT | Sakai: 1936190…1936337 | Hypothetical protein |

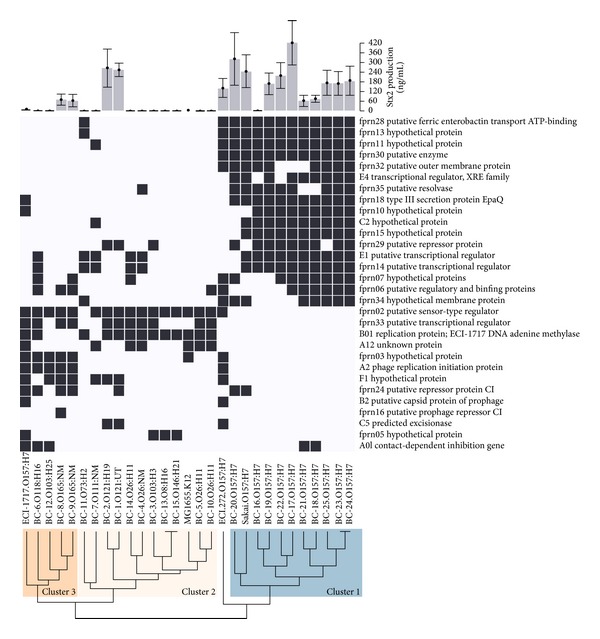

PCR reactions were performed as previously described [28]. Amplicons were visualized on a QIAxcel using the QIAxcel DNA Screening Kit (Qiagen). Binary PCR data were analyzed by constructing an Euclidean distance matrix and hierarchically clustering strains using complete linkage. Analyses were performed in R (http://www.r-project.org/) using the heatmap.2 method of the gplots package (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/index.html). The image was colored using the GNU Image Manipulation Program v2.6.11.

2.6. Lineage Typing of STEC O157

STEC O157:H7 EDL933 and Sakai and FRIK 2001 and ECI-1717 were used as LI and II controls, respectively. The LSPA was carried out according to Yang et al. [19] and analyzed as detailed by Sharma et al. [29].

2.7. AMR Profiling

AMR phenotypes were determined by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion assay. A 5 μL volume of 18 h culture grown in Mueller Hinton broth (MH; BD) was mixed with 5 mL of molten agar (44°C) and overlaid on MH agar. Discs (BD) were placed on the agar surface and incubated (24 h, 37°C), and zones of inhibition measured to the nearest millimeter. Susceptibility was interpreted using CLSI guidelines [30]. In total, 19 antimicrobials were screened: amikacin (AMK; 30 μg), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMX; 30 μg), ampicillin (AMP; 10 μg), cefoxitin (FOX; 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ; 30 μg), ceftiofur (TIO; 30 μg), chloramphenicol (CHL; 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5 μg), erythromycin (ERY; 15 μg), gentamicin (GEN; 10 μg), imipenem (IPM; 10 μg), kanamycin (BCN; 30 μg), nalidixic acid (NAL; 30 μg), neomycin (NEO; 5 μg), rifampicin (RIF; 5 μg), spectinomycin (SPT; 100 μg), streptomycin (STR; 10 μg), tetracycline (TET; 30 μg), and trimethoprim (TMP; 5 μg).

2.8. Genotypic Characterization of AMR

Isolates were screened for the presence of class I, II, and III integrons [31, 32]. A multiplex PCR assay was used to detect the presence of CMY-2, CTX-M, OXA-1, SHV, and TEM β-lactamases [33]. DNA sequencing was used to confirm bla CMY-2 identity.

2.9. AMR Plasmid Association

Approximately 15 ng of plasmid was mixed with electrocompetent E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen). Following electroporation (MicroPulser, BioRad), cells were resuspended in SOC medium (Invitrogen), incubated (2 h, 37°C), plated on LB agar supplemented with AMP (100 μg/mL), CHL (30 μg/mL), or TET (30 μg/mL), and incubated (24 h, 37°C).

Plasmid mobility in MDR strains was evaluated by conjugation with E. coli K802 (NALR), S. Typhimurium MSC001 (NALR), and Citrobacter rodentium MRS0026 (AMPR, NALR). Due to intrinsic resistance to ampicillin, a nonpolar bla deletion was generated in C. rodentium MRS0026 (lambda-red system), rendering it AMP sensitive. Donors/recipients were grown for 18 h in LB broth (37°C) containing appropriate antimicrobials. For both, 400 μL was centrifuged (2000 rpm, 10 min), washed, and resuspended in 400 μL of fresh LB broth. Matings were incubated for 5 h at 37°C on a 400 μL agar slant within a 1.5 mL microfuge tube. The mixture was resuspended in 100 μL LB broth, plated on LB agar with antimicrobials, and incubated (24 h, 37°C). Transconjugants were streaked on LB agar and screened for AMR.

2.10. Quantification of Stx

The production of Stx2 was quantified using polymixin lysis as described in Ziebell et al. [34], with some modification. Bacterial overnight cultures grown at 37°C with shaking (150 RPM) were diluted 1 : 250 and used to inoculate 5 mL of fresh brain heart infusion (BHI) broth in 50 mL Falcon tubes. Subsequently, 0.5 mg/mL of polymixin was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Three experimental replicates were used to assess Stx2 toxin production. Total Stx was assessed using polymixin lysis [34], with slight modification. Cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL polymixin and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Stx2 production differences between clusters were assessed using the t-test function of R.

3. Results

3.1. STEC Serotypes, Clonality, and Virulence Profiles

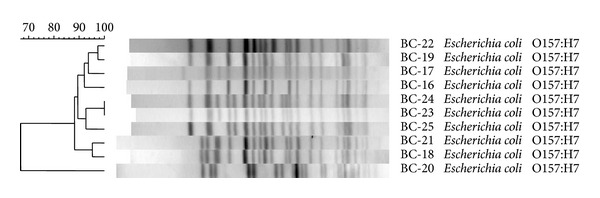

In total, 10 serogroups and 12 unique serotypes were represented in the STEC panel. All O157 serogroup isolates displayed the H7 flagellar antigen. Non-O157 serogroups included O26, O121, and O165 NM variants; the remaining isolates were unique serotypes (Table 2). PFGE of STEC O157 isolates showed two indistinguishable isolates (BC-20 and -21), with all strains being distinguishable despite having ≥88% similarity (Figure 1). In spite of similar pulsotypes, BC-20 and -21 were distinguishable based on differing plasmid profiles and AMR phenotypes. Plasmid profiling revealed that 96% of isolates possessed plasmids which varied in size and number. Overall, 21 of 25 (84%) strains possessed a plasmid similar in size to pO157, with all STEC O157 possessing it. Two non-O157 STEC (O26:H11 and O111:NM) were shown to have seven plasmids.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance, serotypes, PFGE, plasmid, and virulence profiles of clinical STEC isolated from British Columbia.

| Strain no. | Serotype | Virulence genes | XbaI PFGE profile | Plasmid profile (kb) | AMR phenotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| st x 1 a (subtype) | st x 2 (subtype) | ea eA | hl yA | |||||

| BC-13 | O8:H16 | + | + (stx 2) | − | + | ECXA1.2261 | 100, 16, 12, 8, 7 | BCNI, NEOI, SPTI, STRI |

| BC-14 | O26:H11 | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2513 | 93, 14, 7 | NEO, TETI |

| BC-5 | O26:H11 | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2515 | 93, 80, 14, 7, 6, 3.5, 2.5 | NEOI |

| BC-10 | O26:H11 | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2280 | 93, 14, 7 | NEOI, SPTI |

| BC-4 | O26:NM | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2516 | 93, 14, 7 | NEOI, SPTI |

| BC-11 | O73:H2 | − | + (stx 2) | + | + | NDb | 100 | BCNI, SPTI, STR, TETI, NEOI |

| BC-3 | O103:H3 | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2517 | 100, 93, 14, 7, 5 | BCN, NEO, SPTI, TET |

| BC-12 | O103:H25 | + | − | + | + | ECXA1.2262 | 93 | STR, NEOI |

| BC-7 | O111:NM | + | − | + | + | ND | 93, 80, 65, 14, 7, 6, 3.5 | NEOI |

| BC-6 | O118:H16 | + | − | + | + | ND | 93, 14, 7, 6 | BCNI, KANI, NEO, SPT, STR, TET |

| BC-2 | O121:H19 | − | + (stx 2) | + | − | ECXA1.2518 | None | NEOI, SPTI |

| BC-1 | O121:UT | − | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2518 | 93 | NEO, SPTI |

| BC-15 | O146:H21 | + (stx 1c) | − | − | + | ND | 80, 15, 12, 8 | NEOI |

| BC-8 | O165:NM | + | + (stx 2) | + | − | ECXA1.2514 | 93 | AMPI, NEOI, SPT, TETI |

| BC-9 | O165:NM | + | + (stx 2) | + | − | ECXA1.2514 | 93 | NEOI, TETI |

| BC-16 | O157:H7 | − | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.0023 | 93 | NEO |

| BC-17 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2426 | 93 | SPTI |

| BC-18 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2203 | 93, 80, 65 | CHL, NEOI, SPTI, STR, TET |

| BC-19 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.0001 | 93, 70 | TETI |

| BC-20 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2412 | 93, 70, 3.5 | AMC, AMP, FOX, CAZ, TIO, STRI |

| BC-21 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2412 | 93, 80, 65 | CHL, NEOI, STR, TET |

| BC-22 | O157:H7 | − | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2203 | 93, 80, 50, 30 | NEOI |

| BC-23 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.0854 | 93 | NEOI, SPTI |

| BC-24 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.1107 | 93 | NEO, SPTI |

| BC-25 | O157:H7 | + | + (stx 2) | + | + | ECXA1.2397 | 93 | NEOI, SPTI |

aAll were subtype stx 1 with a single exception; bnot determined; Idenotes reduced susceptibility.

Figure 1.

Clustering of STEC O157 by PFGE typing.

All E. coli O157:H7 were eaeA and hlyA positive whilst 13 and 12 of 15 non-O157 STEC were positive, respectively (Table 2). In non-O157 STEC, stx 1 was observed more frequently than stx 2, with 12 of 15 isolates encoding it and only six of 15 harboring stx 2. Only three non-O157 STEC (O8:H16 and O165:NM) possessed both Shiga toxin genes. In contrast, eight of 10 STEC O157 had both, with all possessing stx 2. Subtyping of stx revealed 19 of 20 STEC with Shiga toxin 1 subtyped as stx 1; the remaining isolate (O146:H21) encoded stx 1c. All STEC with Shiga toxin 2 had the stx 2 subtype. LSPA typing showed STEC O157 strains were LI (LSPA-6 111111).

3.2. Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting

All strains had unique CGF fingerprints, with the exception of two O157:H7 (BC-23 and BC-24) and two non-O157 (BC-13 and BC-15) isolates (Figure 2); the O157:H7 groupings mirrored those obtained by PFGE in that they generated identical strain clusters. The dendrogram in Figure 2 shows three clusters of STEC, with cluster (C) 1 consisting of O157:H7 LI strains, C2 of non-O157 STEC of serogroups O26, O146, O8, O121, O111, and O73, and the O103:H3 strain (BC-3), C3 including the O157:H7 LII control strain, all O165:NM and O118:H16 strains, and O103:H25 (BC-12), and C4 containing the O157:H7 LI/II control. C2 strains were positive for the fewest CGF loci, followed in an increasing order by C3, C4, and C1.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering and Stx2 production of 25 clinical STEC strains.

3.3. Stx2 Production

All O157:H7 strains produced Stx2, while only four of six non-O157 STEC encoding stx 2 did, including O121 (BC-1, BC-2) from C2 and O165:NM (BC-8, BC-9) from C3 (Figure 2). Both O121 strains produced levels of Stx2 similar to the STEC O157 Sakai strain. Of the strains that produced Stx2, C1 and C2 strains produced significantly more than C3 strains (P = 0.018 and P = 0.005, respectively). There was no significant difference in Stx2 production between C1 and C2 strains (P = 0.072).

3.4. AMR

All isolates were sensitive to AMK, CIP, GEN, IMP, NAL, RIF, and TMP (Tables 2 and 3). However, 11 of 25 were resistant to at least one antibiotic while reduced susceptibility (RSC) was observed in all remaining strains, particularly to NEO (n = 16), SPT (n = 12), TET (n = 5), BCN (n = 3), and STR (n = 3). The most common resistance was to NEO (n = 6), STR (n = 5) and TET (n = 4). CHL resistance and resistance/RSC to BCN were infrequently observed. Three O157 and two non-O157 STEC were resistant to ≥3 antibiotics, though only O165:NM (BC-8) possessed resistance/RSC to three different classes. Six multidrug resistant (MDR) profiles were observed, including NEO-STR, NEO-SPT, and BCN-NEO-TET in non-O157 STEC (Table 4). These were observed less frequently (0 to 40%) in the 10 O157:H7 isolates. Whilst four of 10 O157:H7 STEC were resistant/RSC to one antibiotic, only three of 15 non-O157 were singularly resistant. Interestingly, BC-20 possessed resistance to AMP, CAZ, and TIO, suggesting the presence of a beta-lactamase affording resistance to extended spectrum cephalosporins (ESC).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) amongst Shiga toxin-producing E. coli.

| Antimicrobial agents | STEC AMR susceptibility (%) | % AMR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Reduced susceptibility | Resistant | Non-O157 STEC (n = 15) | O157 STEC (n = 10) | |

| Aminoglycosides | |||||

| Amikacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kanamycin | 84 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| Neomycin | 0 | 76 | 24 | 27 | 20 |

| Streptomycin | 72 | 8 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Penicillin | |||||

| Ampicillin | 92 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Carbapenem | |||||

| Imipenem | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalosporin | |||||

| Ceftazidime | 96 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Macrolide | |||||

| Erythromycin | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Quinolones | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nalidixic acid | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenicol | |||||

| Chloramphenicol | 92 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 20 |

| Ansamycin | |||||

| Rifampicin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Spectinomycin | |||||

| Spectinomycin | 44 | 48 | 8 | 13 | 0 |

| Tetracylines | |||||

| Tetracycline | 64 | 20 | 16 | 13 | 20 |

| Sulfonamide | |||||

| Trimethoprim | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 4.

Multidrug resistant and reduced susceptibility STEC phenotype patterns.

| Common antibiogram profiles | AMR | |

|---|---|---|

| No. non-O157 STEC (%) | No. O157 STEC (%) | |

| NEO, STR | 10 (67) | 2 (20) |

| NEO, SPT | 9 (60) | 4 (40) |

| BCN, NEO, TET | 3 (20) | 0 |

| SPT, STR, TET | 2 (13) | 0 |

| CHL, STR, TET | 0 | 2 (20) |

| AMP, CAZ, AMC, FOX, CFT | 0 | 1 (10) |

3.5. Molecular AMR Characterization and Mobility

No integrons were detected in any isolate. In BC-20, the presence of bla CMY-2 was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. Transformants were shown to possess a similar 70 kb plasmid and resistance profile and were positive for bla CMY-2. Mating experiments showed that resistance was transferable to E. coli, S. Typhimurium, and C. rodentium through conjugation. Transformations and conjugations were performed using other MDR STEC (Table 5). With the exception of E. coli O118:H16 (BC-6), all strains readily transferred resistance.

Table 5.

AMR phenotype of transformants and transconjugants derived from STEC plasmid DNA and matings, respectively.

| Serotype (strain ID) | Transferred AMR phenotype | Transformants | Transconjugants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | E. coli K802NR | C. rodentium DBS100 | C. rodentium MCS026a | S. Typhimurium MCS001 | ||

| O103:H3 (C) | BCN, NEO, TET | + | + | + | n/ab | + |

| O118:H16 (F) | SPT, STR, TET | − | − | − | n/a | − |

| O157:H7 (3) | CHL, STR, TET | + | + | − | n/a | n/a |

| O157:H7 (5) | AMP, CAZ, AMC, FOX, TIO | +c | +c | n/a | + | + |

| O157:H7 (6) | CHL, STR, TET | + | + | − | n/a | n/a |

a C. rodentium MCS026 was constructed by deleting bla in C. rodentium DBS100.

bNot applicable.

cReduced susceptibility.

4. Discussion

Boerlin et al. [35] reported an association between clinical EHEC serotypes and stx 2 and eae and, to a lesser extent, hlyA. More recently, it was reported that lineage and isolation origin correlate with Stx2 production [21]. Specifically, human LI isolates produce more toxin than cattle LI and LII strains. Also, high-toxin producing LI strains encode stx 2 whereas LII strains possess stx 2c, and LI/II have both. In this study, all E. coli O157:H7 isolates belonged to LI (LSPA-6 111111) and carried the stx 2 subtype. This is consistent with observations made by Sharma et al. [29] who reported 91.6% of clinical strains in Alberta typed as LSPA-6 111111 and elsewhere [17–19]. However, it was recently shown by Franz et al. [36] and Mellor et al. [37] that the majority of clinical STEC O157 in The Netherlands, Argentina, and Australia, respectively, are LI/II strains. As such our study provides further evidence demonstrating that disease-causing STEC O157 in North America differ from STEC causing disease on other continents. When Shiga toxin production was examined, while levels of Stx2 associated with O157 strains were variable, these strains clustered together by CGH and generally produced more Stx2 than non-O157 STEC strains possessing stx 2. Interestingly, STEC O157 BC-17 produced higher levels of toxin than the Sakai strain.

Virulence profiles in non-O157 isolates displayed more variability than O157 STEC. Buvens and Piérard [38] reported a progressive decrease of O-island (OI) 122 components (nleB, nleE) when examining seropathotypes A to D. Further, OI-122 and the presence of stx 2, eae, and espP were present at higher rates in non-O157 causing HUS. Although we did not screen for the presence of OI-122, only five non-O157 STEC possessed both stx 2 and eae. Interestingly, while three of these isolates lacked hlyA, four were the only non-O157 STEC to show significant Stx2 production.

This CGF scheme was developed for O157:H7 STEC [28]. Overall, it performed well, though in one case two STEC from unrelated serogroups (BC-9 and BC-15) were indistinguishable, possessing only three of 30 loci. Previous studies reported low frequencies of O157:H7-specific elements in non-O157 STEC, suggesting independent acquisition of non-O157:H7 traits and that these traits not be included in our CGF scheme [39–41]. Generally, non-O157:H7 strains sharing more elements with O157:H7 STEC grouped into seropathotypes associated with more severe human disease.

Seropathotyping [6] has been useful in assigning risk but is broad in scope. Here O26:H11 (BC-14) was found to differ at 10% of CGF loci from the other O26:H11 strains (BC-5, BC-10). Thus, similar to O157:H7, non-O157 STEC may contain distinct lineages differing in genomic content and their capacity to cause disease. While the resolution provided by seropathotyping and the O157 CGF are helpful in differentiating among strains, complete genome sequence analysis of non-O157 STEC will be required to identify lineage-specific loci among them and the existence of unique “genopathotypes.”

Previous research found only LII O157:H7 STEC possessed cdi [42], which is common in uropathogenic E. coli [43]. In this collection, we observed two LI strains to be positive for cdi. This implies that these isolates have either recently acquired this gene or the original study was not sufficiently broad to capture LI diversity.

At this time, antibiotic administration for human STEC infection is contraindicated in the treatment of STEC infections in North America [44], though conflicting reports of clinical outcomes and antibiotic administration have been made. Antibiotic usage for treatment has been linked to diminished clinical outcomes [45, 46] or had little influence on patient outcomes [47, 48]. In contrast, early administration of fosfomycin was reported to improve clinical outcomes [49]. Recent data from the E. coli O104:H4 outbreak support administration of antibiotics, with fewer seizures, deaths, and surgeries required for antibiotic-treated patients [50]. Further, treated individuals experienced shorter symptom duration and shed the pathogen for significantly less time, thus posing a lower risk of secondary disease transmission [51]. For these reasons, AMR data observed in clinical STEC strains is needed to provide appropriate therapeutic guidance to physicians should the current contraindication be rescinded.

With the recognition of STEC as a significant source of human disease, increased reports of AMR have been made in recent years [14, 52–58]. In this study, though clinical STEC were sensitive to many drugs, RSC in all examined strains examined or resistance in 11 of 25 strains to at least one antibiotic was observed. Similar sensitivity to AMK, various β-lactams, CIP, and TMP has been reported in STEC of diverse origin [53, 54, 56]. Although the sample size in our study is small, levels of AMR were high considering the clinical origins of the strains. For example, in the US higher AMR levels were reported in cattle (34%) and food (20%) compared to clinical (10%) isolates [59]. Similarly, in Spain STEC O157 resistant to one or more antimicrobials were recovered in 53% of bovine and 57% of beef isolates, but only 23% of clinical isolates were resistant [52]. In Alberta, Canada, whilst 34% of bovine isolates were resistant to one of more antimicrobials, only 10% of clinical isolates were resistant with the most commonly observed resistances being to STR, sulfisoxazole, and TET [29]. Although resistance to sulfisoxazole was not screened in our study, NEO, STR, and TET were the most frequently occurring AMR phenotypes.

Notably, BC-20 possessed a plasmidic bla CMY-2. Considering the highly promiscuous nature of plasmid harbouring observed bla CMY-2 in this study and previously reported plasmids encoding it [60, 61], it is not surprising that generic E. coli and STEC O157 possessing a similar plasmid have been recovered from cattle hides, carcasses, processing environments, and ground beef in Canada [62, 63]. Our observation of a clinical STEC possessing RSC to critically important therapeutic agents suggests caution in the administration of ceftriaxone and other therapeutic ESCs that may be considered for treatment of STEC infections.

5. Conclusions

We observed a small collection of clinical STEC in BC to be of variable genomic content. STEC O157 were LI strains producing significant amounts of Stx2. Based on CGF, increased genomic variation was observed in non-O157 STEC strains, with isolates clustering into two distinct groups. CGF and Stx2 assays suggest that serogroups O121 and O165 were more similar to STEC O157 in genetic content than other non-O157 and that these isolates may produce high levels of Stx. However, further work examining clinical O121 and O165 serogroup strains is required to substantiate this assertion. Although this may make these serogroups of greater public health concern than other non-O157 STEC, surveillance data is required to examine the frequency and disease severity that these serogroups cause in human STEC infections. Despite the clinical origins of the non-O157 strains, the genetic variability revealed by our CGF strategy highlights the need for more detailed genetic information, such as that offered by whole genome sequencing. Lastly, we also observed high levels of AMR and RSC in this clinical collection, including a highly mobile bla CMY-2-encoding plasmid conferring resistance to clinically relevant treatment options. Considering recent evidence suggesting that antimicrobial therapy may lead to reduced severity of clinical outcomes, further data examining AMR in STEC seem prudent.

References

- 1.Karmali MA. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli . Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1989;2(1):15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Advisory Committee on Microbiological Safety of Food. Report on Verocytotoxin-Producing Escherichia coli . 1995, http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/acmsfvtecreport.pdf.

- 3.Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli . Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1998;11(1):142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(4):603–609. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.040739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, et al. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11(9):671–676. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karmali MA, Mascarenhas M, Shen S, et al. Association of genomic O island 122 of Escherichia coli EDL 933 with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli seropathotypes that are linked to epidemic and/or serious disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(11):4930–4940. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.4930-4940.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fey PD, Wickert RS, Rupp ME, Safranek TJ, Hinrichs SH. Prevalence of non-O157:H7 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in diarrheal stool samples from Nebraska. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2000;6(5):530–533. doi: 10.3201/eid0605.000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park CH, Kim HJ, Hixon DL. Importance of testing stool specimens for Shiga toxins. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(9):3542–3543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3542-3543.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson LH, Giercke S, Beaudoin C, Woodward D, Wylie JL. Enhanced surveillance of non-O157 verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in human stool samples from Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2005;16(6):329–334. doi: 10.1155/2005/859289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks JT, Sowers EG, Wells JG, et al. Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983–2002. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;192(8):1422–1429. doi: 10.1086/466536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosilevac JM, Koohmaraie M. Prevalence and characterization of non-O157 shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from commercial ground beef in the United States. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77(6):2103–2112. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02833-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreoletti O, Budka H, Buncic S. Scientific opinion of the panel on biological hazards on a request from EFSA on monitoring of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC) and identification of human pathogenic VTEC types. The EFSA Journal. 2007;579:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bettelheim KA. The non-O157 Shiga-toxigenic (verocytotoxigenic) Escherichia coli; under-rated pathogens. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2007;33(1):67–87. doi: 10.1080/10408410601172172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Käppeli U, Hächler H, Giezendanner N, Beutin L, Stephan R. Human infections with non-o157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Switzerland, 2000–2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(2):180–185. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Agriculture. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in certain raw beef products. 2011, http://www.fsis.usda.gov/Frame/FrameRedirect.asp?main=http://www.fsis.usda.gov/OPPDE/rdad/FRPubs/2010-0023FRN.htm.

- 16.Manning SD, Motiwala AS, Springman AC, et al. Variation in virulence among clades of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with disease outbreaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(12):4868–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710834105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Nietfeldt J, Benson AK. Octamer-based genome scanning distinguishes a unique subpopulation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains in cattle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(23):13288–13293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Nietfeldt J, Ju J, et al. Ancestral divergence, genome diversification, and phylogeographic variation in subpopulations of sorbitol-negative, β-glucuronidase-negative enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183(23):6885–6897. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6885-6897.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Kovar J, Kim J, et al. Identification of common subpopulations of non-sorbitol-fermenting, β-glucuronidase-negative Escherichia coli O157:H7 from bovine production environments and human clinical samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(11):6846–6854. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6846-6854.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Laing C, Steele M, et al. Genome evolution in major Escherichia coli O157:H7 lineages. BMC Genomics. 2007;8, article 121 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Laing C, Zhang Z, et al. Lineage and host source are both correlated with levels of shiga toxin 2 production by Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(2):474–482. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01288-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. British Columbia annual summary of reportable diseases. 2011, http://www.bccdc.ca/util/about/annreport/default.htm.

- 23.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, et al. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2006;3(1):59–67. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed- field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1995;33(9):2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paton AW, Paton JC. Detection and characterization of shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfb(O111), and rfb(O157) Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36(2):598–602. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.598-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephan R, Hoelzle LE. Characterization of shiga toxin type 2 variant B-subunit in Escherichia coli strains from asymptomatic human carriers by PCR-RFLP. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2000;31(2):139–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beutin L, Miko A, Krause G, et al. Identification of human-pathogenic strains of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from food by a combination of serotyping and molecular typing of Shiga toxin genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(15):4769–4775. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00873-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laing C, Pegg C, Yawney D, et al. Rapid determination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 lineage types and molecular subtypes by using comparative genomic fingerprinting. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(21):6606–6615. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00985-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma R, Stanford K, Louie M, et al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 lineages in healthy beef and dairy cattle and clinical human cases in alberta, Canada. Journal of Food Protection. 2009;72(3):601–607. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.3.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twentieth informal supplement M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010;30:1–153. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu H, Davies J, Miao V. Molecular characterization of class 3 integrons from Delftia spp. Journal of Bacteriology. 2007;189(17):6276–6283. doi: 10.1128/JB.00348-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Broersma K, Miao V, Davies J. Class 1 and class 2 integrons in multidrugresistant gram-negative bacteria isolated from the Salmon River, British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2011;57(6):460–467. doi: 10.1139/w11-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mataseje LF, Bryce E, Roscoe D, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in Canada 2009-10: results from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67(6):1359–1367. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziebell K, Steele M, Zhang Y, et al. Genotypic characterization and prevalence of virulence factors among Canadian Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(14):4314–4323. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02821-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boerlin P, McEwen SA, Boerlin-Petzold F, Wilson JB, Johnson RP, Gyles CL. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37(3):497–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.497-503.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franz E, Van Hoek AHAM, Van Der Wal FJ, et al. Genetic features differentiating bovine, food, and human isolates of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in The Netherlands. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012;50(3):772–780. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05964-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellor GE, Sim EM, Barlow RS, et al. Phylogenetically related Argentinean and Australian Escherichia coli O157 isolates are distinguished by virulence clades and alternative Shiga toxin 1 and 2 prophages. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(13):4724–4731. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00365-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buvens G, Piérard D. Virulence profiling and disease association of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 and non-O157 isolates in Belgium. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2012;9(6):530–535. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid SD, Herbelin CJ, Bumbaugh AC, Selander RK, Whittam TS. Parallel evolution of virulence in pathogenic Escherichia coli . Nature. 2000;406(6791):64–67. doi: 10.1038/35017546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogura Y, Ooka T, Asadulghani A, et al. Extensive genomic diversity and selective conservation of virulence-determinants in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains of O157 and non-O157 serotypes. Genome Biology. 2007;8(7, article R138) doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyle JL, Cummings CA, Parker CT, et al. Escherichia coli serotype O55:H7 diversity supports parallel acquisition of bacteriophage at Shiga toxin phage insertion sites during evolution of the O157:H7 lineage. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194(8):1885–1896. doi: 10.1128/JB.00120-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steele M, Ziebell K, Zhang Y, et al. Genomic regions conserved in lineage II Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(10):3271–3280. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02123-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoki SK, Pamma R, Hernday AD, Bickham JE, Braaten BA, Low DA. Microbiology: contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli . Science. 2005;309(5738):1245–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong CS, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, Watkins SL, Tarr PI. The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(26):1930–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dundas S, Todd WTA, Stewart AI, Murdoch PS, Chaudhuri AKR, Hutchinson SJ. The central Scotland Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak: risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome and death among hospitalized patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33(7):923–931. doi: 10.1086/322598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin DL, MacDonald KL, White KE, Soler JT, Osterholm MT. The epidemiology and clinical aspects of the hemolytic uremic syndrome in Minnesota. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(17):1161–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010253231703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell BP, Griffin PM, Lozano P, Christie DL, Kobayashi JM, Tarr PI. Predictors of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children during a large outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1, article E12) doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda K, Ida O, Kimoto K, Takatorige T, Nakanishi N, Tatara K. Effect of early fosfomycin treatment on prevention of hemolytic uremic syndrome accompanying Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. Clinical Nephrology. 1999;52(6):357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menne J, Nitschke M, Stingele R, et al. Validation of treatment strategies for enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic uraemic syndrome: case-control study. British Medical Journal. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4565.e4565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nitschke M, Sayk F, Härtel C, et al. Association between azithromycin therapy and duration of bacterial shedding among patients with shiga toxin-producing enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O104:H4. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(10):1046–1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mora A, Blanco JE, Blanco M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 and non-O157 strains isolated from humans, cattle, sheep and food in Spain. Research in Microbiology. 2005;156(7):793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srinivasan V, Nguyen LT, Headrick SI, Murinda SE, Oliver SP. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O157:H7- from different origins. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2007;13(1):44–51. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fratamico PM, Bhagwat AA, Injaian L, Fedorka-Cray PJ. Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from swine feces. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2008;5(6):827–838. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gow SP, Waldner CL. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors stx1, stx2, and eae in generic Escherichia coli isolates from calves in western Canadian cow-calf herds. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2009;15(1):61–67. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buvens G, Bogaerts P, Glupczynski Y, Lauwers S, Piérard D. Antimicrobial resistance testing of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli and first description of TEM-52 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in serogroup O26. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54(11):4907–4909. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00551-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cergole-Novella MC, Pignatari ACC, Castanheira M, Guth BEC. Molecular typing of antimicrobial-resistant Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains (STEC) in Brazil. Research in Microbiology. 2011;162(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li M-C, Wang F, Li F. Identification and molecular characterization of antimicrobial-resistant shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from retail meat products. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2011;8(4):489–493. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng J, Zhao S, Doyle MP, Joseph SW. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O157:NM isolated from animals, food, and humans. Journal of Food Protection. 1998;61(11):1511–1514. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.11.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allen KJ, Poppe C. Occurrence and characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins mediated by β-lactamase CMY-2 in Salmonella isolated from food-producing animals in Canada. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 2002;66(3):137–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mataseje LF, Baudry PJ, Zhanel GG, et al. Comparison of CMY-2 plasmids isolated from human, animal, and environmental Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. from Canada. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2010;67(4):387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aslam M, Service C. Antimicrobial resistance and genetic profiling of Escherichia coli from a commercial beef packing plant. Journal of Food Protection. 2006;69(7):1508–1513. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.7.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aslam M, Diarra MS, Service C, Rempel H. Antimicrobial resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolates recovered from a commercial beef processing plant. Journal of Food Protection. 2009;72(5):1089–1093. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.5.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]