Abstract

Successful tissue-engineering strategies for cartilage repair must maximize the efficacy of chondrocytes within their limited life span. To that end, the combination of exogenous growth factors with mechanical stimuli holds promise for development of clinically relevant cartilage tissue substitutes. The current study aimed to determine whether incorporation of transient exposure to growth factors into a hydrodynamic bioreactor system can improve the functional maturation of tissue-engineered cartilage. Chondrocyte-seeded polyglycolic acid scaffolds were cultivated within a wavy-walled bioreactor that imparts fluid flow-induced shear stress for 4 weeks. Constructs were nourished with 100 ng/mL insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) or 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) either for the first 15 days of the culture (transient) or throughout the entire cultivation (continuous). Transiently treated constructs were found to exhibit better functional properties than continuously nourished constructs. The limited development of engineered tissues continuously stimulated by IGF-1 or TGF-β1 was related to massive growth factor leftovers in the environments that downregulated the expression of the associated receptors. Treatment with TGF-β1 eliminated the formation of a fibrous capsule at the construct periphery possibly through suppression of Smad3 phosphorylation, yielding constructs with greater homogeneity. Furthermore, TGF-β1 reversely regulated Smad2 and Smad3 pathways in articular chondrocytes under hydrodynamic stimuli partially via Smad7. Collectively, transient exposure to growth factors is likely to maintain chondrocyte homeostasis, and thus promotes their anabolic activities under hydrodynamic stimuli. The present work suggests that robust hydrodynamically engineered neocartilage with a reduced fibrotic response and enhanced tissue homogeneity can be achieved through optimization of growth factor supplementation protocols and potentially through manipulation of intracellular signals such as Smad.

Introduction

Arthritis, a form of musculoskeletal disorders that involves joint inflammation and cartilage breakdown, affects 50 million Americans, resulting in costs of $128 billion annually.1 Articular cartilage is a lubricant substrate that serves as a cushion between the bones of diarthrodial joints, but only has a limited ability for self-healing due to its avascular nature. Tissue engineering is a promising technique for restoration of small cartilage defects, which typically involves cultivation of chondrocytes on three-dimensional biodegradable scaffolds or hydrogels within controlled environments of bioreactor systems.2 To be clinically relevant, cartilage substitutes must meet specific functional criteria related to their mechanical properties, biochemical composition, tissue ultrastructure, immunological compatibility, and integration capability. However, all of these properties of tissue-engineered cartilage are still inferior to those of native tissues.

Fluid flow plays a key role in cartilage development. In vivo, joint movement during normal walking or exercise not only alters pericellular concentrations of biomolecules, driving protein or ion flux in and out of the tissue, but forces the exchange of nutrients and waste between the interstitial fluid within cartilage and the surrounding synovial fluid. The individual contributions of diffusion and convection to protein transport within cartilage have been examined.3,4 These studies revealed that when cartilage is stimulated by fluid flowing at a velocity of 1 μm/s (flow velocity within cartilage at normal walking frequencies5), the efficiency of mass transfer of solutes is tremendously improved. Turbulent flow-induced shear environments can be established within a simple mechanically stirred bioreactor referred to as a spinner flask.6–8 Under mixing, oxygen and nutrients can efficiently be delivered to cells seeded within and/or on scaffolds. Yet, cultured cells can also be damaged when exposed to extremely high agitation rates (150–300 rpm).9 Therefore, it is important to find a balance between hydrodynamic parameters and cell/tissue growth. A wavy-walled bioreactor system (WWB, [Fig. 1A]) designed in our laboratory is an alternative version of the spinner flask whose circular wall is modified into a sinusoidal curve. The unique hydrodynamic environment within the WWB was characterized using computational fluid dynamics simulation, which was further validated by particle image velocimetry methods.10,11 Compared with the spinner flask, the WWB yields enhanced chondrocyte aggregation,12 increased cell-seeding efficiency,13 and improved cell proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition within constructs.14,15 An artificial neural network model was established to correlate hydrodynamic parameters with functional properties of neocartilage grown within the WWB and suggests an optimal agitation rate of 50 rpm.16

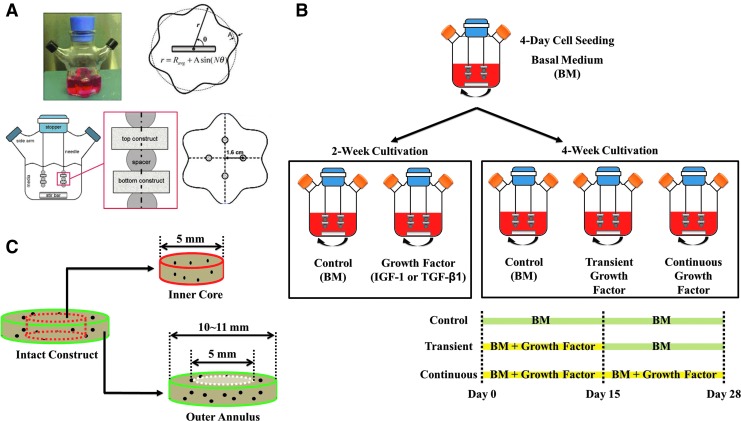

FIG. 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental design. (A) The inner wall of the wavy-wall bioreactor (WWB) can be expressed as a sinusoidal curve: r=Ravg+Asin(N θ) in which Ravg represents the average radius (3.35 cm), A is the wave amplitude (0.45 cm), N is the number of lobes (6), and r and θ are the cylindrical coordinates. A WWB system is equipped with two Teflon side-arm caps, a rubber stopper, a stir bar (Ø0.8 cm×4 cm long), and a stirrer. Four 6-inches-long, 21-gauge needles are inserted through the stopper at equidistant positions (r=1.6 cm). (B) Chondrocyte-seeded constructs were nourished with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) or transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and cultivated in the WWBs for 4 weeks. For transiently treated constructs, growth factor supplementation was discontinued at day 15 and culture media were switched to the basal medium (BM) for the rest of the cultivation. Bioreactors were collected at either day 14 or day 28. (C) Radial variations in construct properties between inner cores and outer annuli were evaluated by coring a 5-mm disc from each construct transiently nourished with IGF-1 or TGF-β1. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Growth factors and cytokines are required for cell growth and tissue development. However, Gooch et al. demonstrated that treatment with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) did not further improve ECM production by chondrocytes cultivated within the spinner flask.8 A possible explanation for this outcome is that these experiments employed a high serum (10%) content, which contains endogenous growth factors, antibodies, and binding proteins that may interfere with the function of exogenous growth factors.17 To resolve this issue, we recently developed a low-serum (2%) medium for the WWB cultivation of chondrocyte-seeded constructs that are morphologically and functionally similar to the high-serum samples.18

Another solution to this problem could be the shortened supplementation of exogenous growth factors, which has recently been utilized to facilitate chondrogenesis of chondrocyte-19,20 or mesenchymal stem cell-laden21,22 hydrogels under static or dynamically compressive conditions. As Byers et al. suggested, it may be that cultured cells require substantial time of ∼2 weeks to adapt themselves to signaling cascades resulting from growth factor removal from the surroundings before exhibiting stronger anabolic potential for ECM synthesis.20 Yet, this beneficial effect has not been validated in hydrodynamic cultures. To extend our knowledge, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility of transient exposure of tissue-engineered cartilage to growth factors under continuous fluid shear stress induced within the WWB. Our central hypothesis was that hydrodynamic constructs transiently nourished with exogenous growth factors will exhibit improved tissue properties over those continuously treated with the same bioactive molecules. We chose IGF-1 and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), two of the key stimulating agents in cartilage development, as our model molecules. For each molecule, a minimal concentration was selected from their most commonly reported ranges of effective doses for neocartilage cultivation (IGF-1: 100–300 ng/mL; TGF-β1: 10–30 ng/mL23–25). By quantifying the amount of growth factors secreted into culture media and the level of expression of the corresponding surface receptors by cultured cells, we explored a possible mechanism that accounts for the transient phenomenon.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unless specified otherwise, reagents were purchased from VWR (West Chester, PA), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), or Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY).

Bioreactor and scaffold preparation

WWBs were modified from spinner flasks (Bellco Glass, Inc., Vineland, NJ) based on the configuration shown in Figure 1A. Three days before cell isolation, interiors of WWBs, needles, and stir bars were treated with Sigmacote® to prevent cell adherence. After evaporation of Sigmacote, assembled bioreactors were washed, air-dried, and steam-sterilized. Polyglycolic acid (PGA)(Biomedical Structures, Warwick, RI) discs (Ø10×2 mm thick, 85 mg/mL bulk density) were sterilized by a series of rinses in sterile 70% ethanol and deionized water, followed by a 30-min exposure to ultraviolet light.18 Two of the sterilized PGA discs were threaded onto each of the 21-gauge needles and separated by a silicone spacer, resulting in totally eight scaffolds per bioreactor. The WWBs were then filled with 120 mL of the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and allowed to stabilize overnight with a stir bar spinning at 50 rpm inside a humidified, 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell isolation, cell seeding, and construct cultivation

Articular chondrocytes were isolated from femoropatellar grooves of freshly slaughtered 2-week-old calves (Research 87, Marlborough, MA) by digestion with type II collagenase as previously described.26 Before each experiment, chondrocytes harvested from three donors were pooled together. Cell number and viability (>85%) were determined using a trypan blue exclusion assay. A small aliquot of cells in suspension was added to each of the sterilized WWBs at a density of 5 million live cells per scaffold. Cell seeding was carried out in the basal medium (BM: DMEM, 2% fetal bovine serum, 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium [ITS], 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 0.4 mM L-proline, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acid, 3.6 mg/mL sodium bicarbonate, 2.5 μg/mL fungizone, and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid) and allowed to proceed for 4 days under fluid agitation (50 rpm) until 95% of the cells achieved attachment.

At the end of the seeding process, media were completely replaced with fresh BM. This point was considered as day 0. Chondrocyte/PGA complexes were then cultured in the WWBs agitated at 50 rpm for 28 days and media were completely renewed every 3 days thereafter. In the groups nourished with growth factors, 100 ng/mL IGF-1 or 10 ng/mL TGF-β1(recombinant human proteins, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to fresh BM during medium exchanges either for the first 15 days of the culture (transient) or throughout the entire 4-week cultivation (continuous). Bioreactors were collected at designated time points (Fig. 1B) and engineered tissues were harvested for evaluation. Radial variations in tissue properties of constructs transiently nourished with exogenous growth factors were also investigated. A 5-mm central core was punched out of each of the 28-day constructs and properties of inner cores and outer annuli were compared (Fig. 1C). For the Smad study, constructs were also cultivated in the WWBs without fluid agitation (static).

Biomechanics

Equilibrium compressive moduli of constructs were determined using an unconfined compression test. During examination, a preload of 0.01 N was applied to samples until equilibrium was achieved. A stress relaxation test was carried out at strains of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25%, after which, samples were allowed to equilibrate. Equilibrium moduli were obtained from the slope of the plot of equilibrium force normalized to the cross-sectional area of the construct versus the strains.

Biochemistry

Before the biochemical assays, constructs were weighed (wet weight), frozen, lyophilized, and then digested with the papain enzyme. DNA weights were quantified using a PicoGreen dsDNA kit and the manufacturer's instructions were followed. Cell numbers were calculated by assuming 7.7 pg of DNA per chondrocyte. Sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) contents were assessed using a 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue dye-binding assay. Chondroitin sulfate (CS) was used to create a standard curve and a CS-to-GAG ratio of 1 was assumed. Total collagen amounts were determined using an orthohydroxyproline (OHP) colorimetric assay, assuming a 1:10 OHP-to-collagen ratio. For compositional analysis of collagen, papain-digested samples were further incubated with 1 mg/mL pancreatic elastase in a 1× Tris-buffered saline solution for 48 h at 4°C to cleave intra- and intermolecular crosslinkages of collagen. Type I and II collagen contents were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based detection kits (Chondrex, Redmond, WA). Results are presented in values normalized to the wet weight or DNA weight of constructs.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Concentrations of IGF-1 and active TGF-β1 in waste media and levels of IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) and TGF-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) in engineered tissues were quantified using DuoSet ELISA Developmental kits (R&D Systems) and the manufacturer's instructions were followed. For detection of IGF-1R and TGF-βRII, one half of each of harvested constructs was lysed and homogenized in a 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer plus protease inhibitors, followed by a 15-min centrifugation at 10,000g at 4°C. The supernatant was collected for ELISA and IGF-1R and TGF-βRII contents were estimated with recombinant human proteins, given the 97% and 91% similarity of amino acid sequence for IGF-1R and TGF-βRII, respectively. The other half was assessed to obtain the DNA amount. Data are presented in values normalized to the corresponding DNA weight.

Western blot

Proteins were isolated as described in the section of ELISA and the total protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit. Equal amounts of proteins were electrophoresed on 10% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then incubated with a blocking buffer for 1 h and purified rabbit antibodies against phospho-Smad2 (pSmad2), phospho-Smad3 (pSmad3), or Smad7 (1:1000) overnight. After several washes, the membranes were treated with IRDye 800CW secondary antibodies (1:5000, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h. Images were visualized using an infrared scanner (Odyssey, Li-Cor).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Constructs were fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned in 5-μm-thick slices. The slices were deparaffinized and stained for GAG and collagen using Safranin-O/fast green and Masson's trichrome methods, respectively.

IGF-1R, TGF-βRII, type I and II collagen molecules were stained immunohistochemically. Briefly, deparaffinized sections were incubated with a citrate buffer heated to 99°C for 25 min to retrieve antigens, followed by a 20-min cooling at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, the blocking buffer for 20 min, and primary rabbit anti-bovine antibodies (1:1500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight. Finally, the sections were treated with biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:200, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min and the streptavidin-conjugated horseradish–peroxidase complex (Vector Labs) for another 30 min, followed by incubation with the diaminobenzidine chromogen reagent until optimal staining was developed. Samples incubated with normal rabbit serum substituted for primary antibodies were used as negative controls and no nonspecific staining was observed (images are available upon request). Color images were captured under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Japan).

Statistical analyses

Statistical data were obtained from experiments repeated two (radial variations) or three (transient versus continuous) times with two to three replicates per group per time point per experiment and are presented as means±one standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance in conjunction with the Bonferroni post test for multiple comparisons (p<0.05).

Results

Tissue properties and morphologies

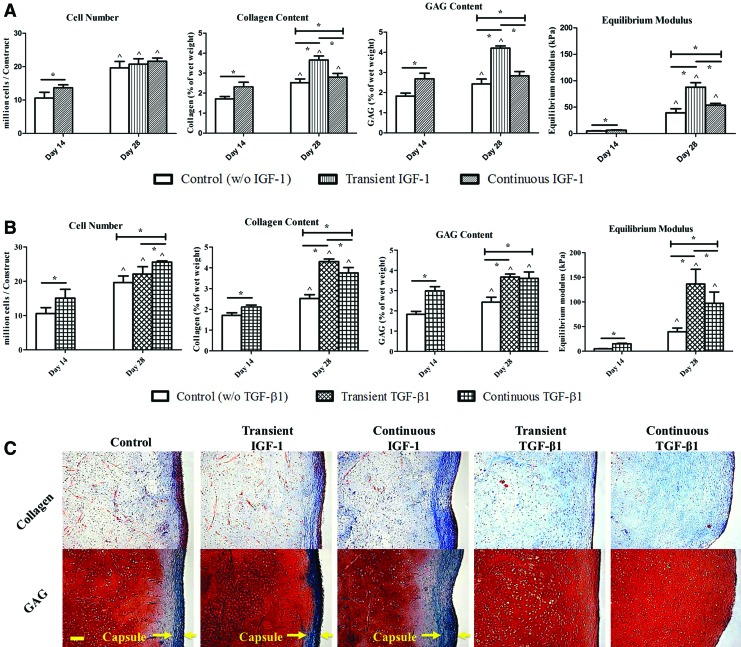

When stimulated by IGF-1 (Fig. 2A) or TGF-β1 (Fig. 2B), 14-day constructs exhibited increased cell proliferation and functional properties compared with the untreated samples (*p<0.05). At day 28, although treatment with exogenous growth factors did not necessarily result in a higher cell content, the nourished groups yielded neocartilage biochemically and mechanically stronger than those in the control group, while transient exposure to growth factors further enhanced construct properties in both IGF-1 and TGF-β1 cases (*p<0.05). Specifically, transient IGF-1 constructs had predominant collagen (3.66%±0.20% of wet weigh vs. 2.52%±0.19% [control] and 2.80%±0.18% [continuous]) and GAG (4.21%±0.11% of wet weight vs. 2.43%±0.25% [control] and 2.83%±0.21% [continuous]) accumulation and equilibrium moduli (87.82±8.48 kPa vs. 39.43±7.63 kPa [control] and 52.73±3.36 kPa [continuous]). Similar trends were recognized inTGF-β1 experiments in which, the highest biochemical contents (4.30%±0.13% of wet weight in collagen and 3.67%±0.15% of wet weight in GAG) and mechanical stiffness (136.43±29.99 kPa) were detected in the transient group although GAG contents of transient and continuous TGF-β1 constructs were not statistically different. However, the difference between transient and continuous TGF-β1 groups largely decreased.

FIG. 2.

(A, B) Cell number, total collagen content, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content, and equilibrium compressive modulus of IGF-1 (A) and TGF-β1 (B) constructs. ^Significant difference from the corresponding 14-day value; *statistical significance between the groups; p<0.05; n=7. (C) Histological images of 28-day constructs. Top row: collagen is stained blue. Bottom row: GAG and cytoplasm are stained red and green, respectively. Arrows indicate the structure of the fibrous capsule. Images were taken under the same optical conditions for each molecule. Scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

At the end of the cultivation, a fibrous outer capsule that is characterized by increased cell density and decreased GAG deposition and consists mainly of type I collagen was observed at the periphery of both control and IGF-1 constructs (Fig. 2C). Conversely, exposure toTGF-β1 eliminated the capsule formation regardless of the duration of the supplementation.

IGF-1 and TGF-β1in waste culture media

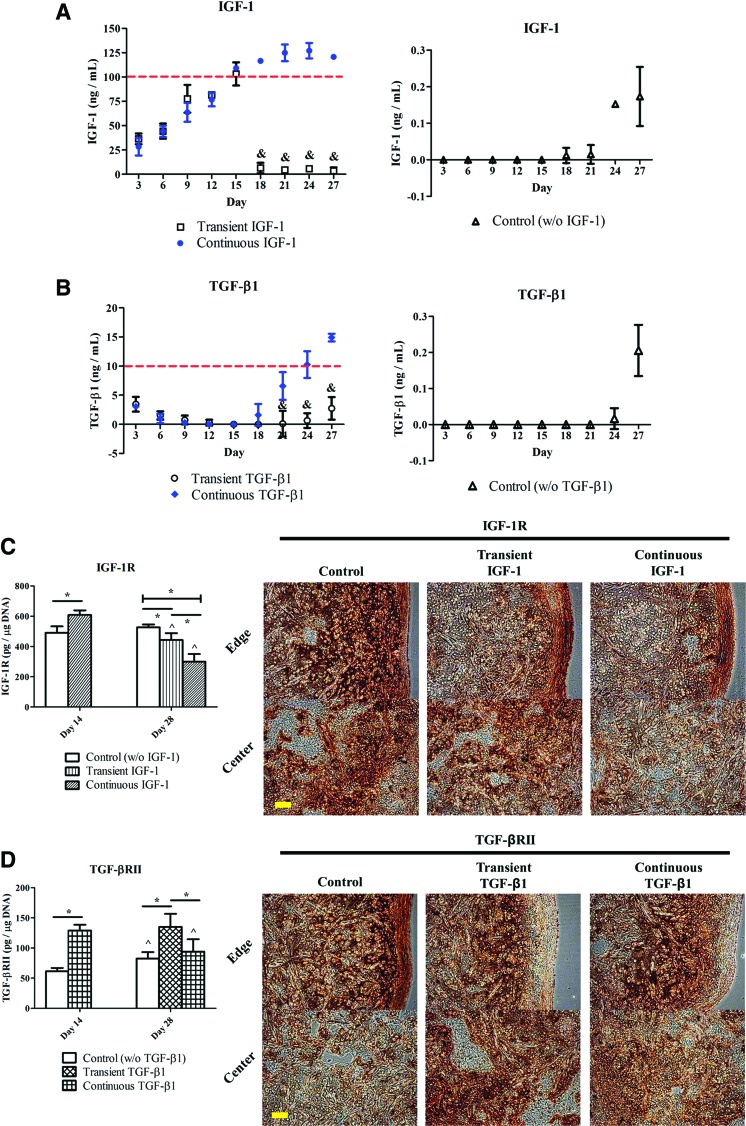

IGF-1 or active TGF-β1 in waste media was quantified every 3 days to obtain the uptake/release curves of each molecule. The IGF-1 concentration (Fig. 3A, left) in the continuous IGF-1 group rose over time and reached a steady-state level after 21 days in culture. Yet, the TGF-β1 level (Fig. 3B, left) in the continuous TGF-β1 group gradually decreased in the first 2 weeks of the cultivation, then began to rise at day 18, and continuously increased thereafter. The IGF-1 and TGF-β1 concentrations detected in the corresponding continuous groups at day 27 were 120.68±2.00 ng/mL and 14.90±0.65 ng/mL, respectively. In both transient groups, growth factor levels remained relatively low and constant after 2 weeks in culture (&p<0.05). The control group showed extremely low concentrations of IGF-1 (Fig. 3A, right) and TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B, right), which were only detectable toward the end of the 4-week cultivation.

FIG. 3.

(A, B) Quantification of IGF-1 (A) and TGF-β1 (B) in waste culture media in the IGF-1 and TGF-β1 experiments, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the concentrations of exogenous growth factors initially added to fresh media during medium exchanges in the continuous groups. &Significant difference from the continuous group at the same time point; p<0.05; n=6. (C, D) Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) (C) and TGF-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) (D) in the IGF-1 and TGF-β1 experiments, respectively. IGF-1R and TGF-βRII contents were estimated with the corresponding recombinant human proteins. IGF-1R and TGF-βRII are stained brown in the corresponding 28-day constructs. Images were taken under the same optical conditions for each molecule. ^Significant difference from the corresponding 14-day value; *statistical significance between the groups; p<0.05; n=6; scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

IGF-1R and TGF-βRII

Quantification of IGF-1R (Fig. 3C) and TGF-βRII (Fig. 3D) in the respective experiments indicated that, at day 14, chondrocytes nourished with either growth factor expressed more receptors than the untreated ones (*p<0.05). Figure 3C reveals that reduced IGF-1R expression was determined at day 28 in both transient (442.86±45.59 pg/μg DNA) and continuous (300.50±50.08 pg/μg DNA) IGF-1 groups compared with the corresponding group at day 14 (608.51±30.58 pg/μg DNA) (^p<0.05). At day 28, the IGF-1R level in the transient IGF-1 group was found to be significantly higher than that in the continuous IGF-1 group, while both values were compromised relative to the control group (526.08±19.65 pg/μg DNA) (*p<0.05). Immunohistochemistry confirmed that the untreated samples contained the most intense IGF-1R staining at day 28.

Figure 3D demonstrates that chondrocytes transiently exposed to TGF-β1 expressed TGF-βRII at a level of 135.10±21.61 pg/μg DNA at day 28, which remained similar to the corresponding 14-day value (129.14±9.65 pg/μg DNA), but was significantly higher than the other groups at the same time point (*p<0.05). Qualitatively, the control specimens were intensely stained for TGF-βRII in the region close to the edge of neocartilage, whereas both transient and continuous TGF-β1 specimens showed extremely weak TGF-βRII signals at the construct periphery, but higher toward the central portion of constructs.

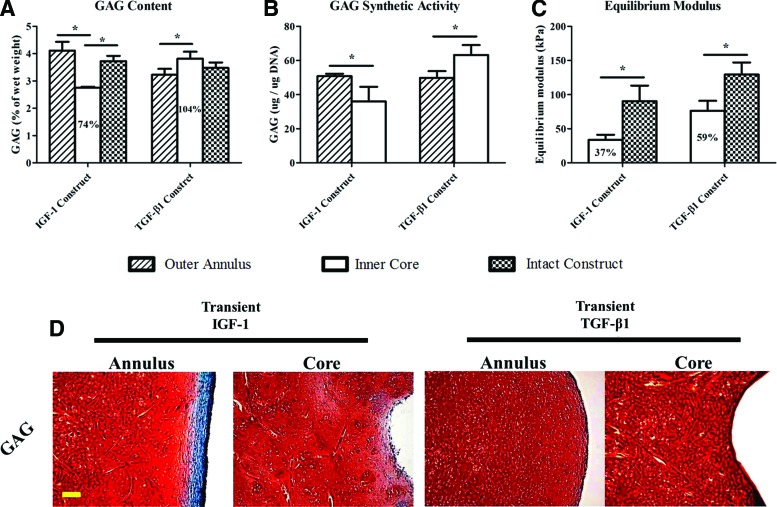

Radial variations

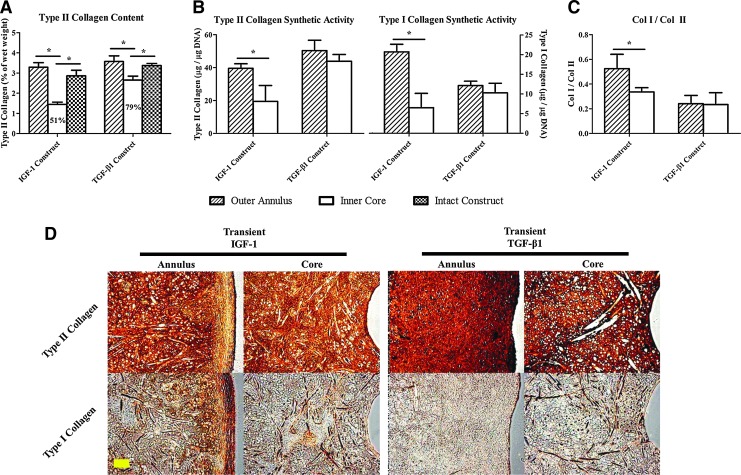

Evaluation of radial variations (transient constructs only) showed that IGF-1 (1.45%±0.11% of wet weight) and TGF-β1(2.65%±0.20% of wet weight) inner cores reached 51% and 79% of the collagen II contents achieved by the respective intact constructs and either inner core value was also lower than the corresponding outer annulus level (*p<0.05) (Fig. 4A). When values were normalized to the DNA weight (Fig. 4B), chondrocytes in the IGF-1 outer annuli produced a greater amount of collagen, including both type II (39.53±2.79 μg/μg DNA) and type I (20.72±1.93 μg/μg DNA) relative to those in the inner cores (*p<0.05), whereas comparable collagen synthetic activities were detected throughout TGF-β1 constructs. A significant difference in the collagen I-to-II ratio (Fig. 4C) between outer annuli and inner cores was identified in the IGF-1 group (annulus: 0.52±0.12; core: 0.34±0.03) (*p<0.05). TGF-β1 specimens were more intensely stained for type II collagen than IGF-1 specimens in both the outer annulus and inner core (Fig. 4D). Moreover, intense collagen I staining was observed in the IGF-1 outer annuli.

FIG. 4.

(A) Type II collagen content, (B) type II and type I collagen synthetic activities, and (C) collagen I to II ratio of outer annuli and inner cores of 28-day constructs transiently supplemented with IGF-1 or TGF-β1. Percentages represent the inner core values normalized to the corresponding intact construct values. *Statistical significance between the groups; p<0.05; n=4. (D) Immunohistochemical staining of type II and type I collagen in 28-day transient constructs. Collagen molecules are stained brown. Images were taken under the same optical conditions for each molecule. Scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

In GAG analysis, the TGF-β1 inner cores (3.82%±0.25% of wet weight) contained a GAG composition equivalent to that of the intact TGF-β1 constructs (3.48%±0.20% of wet weight), whereas the IGF-1 inner cores (2.75%±0.04% of wet weight) had a compromised GAG content in comparison with both the outer annulus (4.11%±0.33% of wet weight) and the intact construct(3.73%±0.19% of wet weight) values (*p<0.05) (Fig. 5A). While cells in the IGF-1 inner cores (36.03±8.53 μg/μg DNA) exhibited significantly weaker GAG synthetic potential than those in the outer annuli (50.80±1.44 μg/μg DNA), opposite behavior was recognized in the TGF-β1 group (*p<0.05) (Fig. 5B). Biomechanically, equilibrium moduli of IGF-1 (33.72±7.61 kPa) and TGF-β1 (76.40±14.44 kPa) inner cores matched 37% and 59% of the corresponding intact construct values, respectively (Fig. 5C). In histology, intense GAG staining was observed throughout the TGF-β1 constructs (Fig. 5D), while IGF-1 specimens confirmed that the capsule consisted mainly of type I collagen (Fig. 4D & 5D).

FIG. 5.

(A) GAG content, (B) GAG synthetic activity, and (C) equilibrium compressive modulus of outer annuli and/or inner cores of 28-day constructs transiently supplemented with IGF-1 or TGF-β1. Percentages represent the inner core values normalized to the corresponding intact construct values. *Statistical significance between the groups; p<0.05; n=4. (D) Histological staining of GAG in 28-day transient constructs. GAG and cytoplasm are stained red and green, respectively. Images were taken under the same optical conditions. Scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Smads

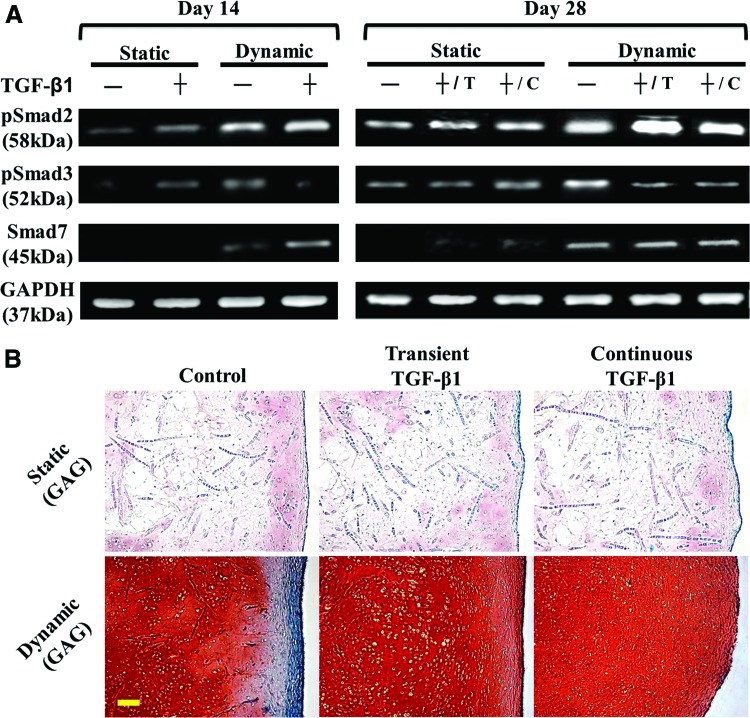

Regulation of major intracellular mediators in TGF-β signaling by TGF-β1 and hydrodynamic forces was evaluated. In this study, constructs were cultivated with or without TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of fluid agitation. Western blot results (Fig. 6A) revealed that, without TGF-β1, more Smad2 and Smad3 were phosphorylated under hydrodynamic stimuli at days 14 and 28. In both, the static and dynamic groups, TGF-β1-nourished samples demonstrated more intense pSmad2 than the untreated samples at the same time points. However, relative to the untreated groups, TGF-β1 increased pSmad3 signals under static conditions, but decreased its intensity in the presence of fluid shear at both time points. At day 28, the dynamic group with shortened TGF-β1 nourishment (+/T) did not surrender pSmad2 and pSmad3 in comparison with that under continuous TGF-β1 stimulation (+/C). Smad7 was only determined in the dynamic groups. Specifically, stronger Smad7 signals were detected in the TGF-β1-treated group at day 14, whereas similar intensity was observed among the groups at day 28.

FIG. 6.

(A) Western blot of phospho-Smad2 (pSmad2), phospho-Smad3 (pSmad3), Smad7, and GAPDH. Chondrocyte-seeded constructs were cultivated with (+) or without (−) TGF-β1 in the presence (dynamic) or absence (static) of fluid shear stress induced within the WWB. T: transient; C: continuous. (B) Staining of GAG in 28-day constructs cultured under the specified conditions. GAG and cytoplasm are stained pink/red and green, respectively. Images were taken with the same optical parameters for each loading condition. Scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Discussion

In this study, chondrocyte-seeded PGA scaffolds were cultured transiently or continuously with IGF-1 or TGF-β1 in the WWBs for 4 weeks. Our results reveal that IGF-1 and TGF-β1 effectively promoted the early development of neocartilage, suggesting that the early growth factor supply is required to enhance cell signaling and communication. Yet, engineered tissues did not largely benefit from continuous growth factor stimulation over time, especially in IGF-1 cultures (Fig. 2). This implies that prolonged exposure to IGF-1 may constrain the development of hydrodynamic constructs. Conversely, discontinuation of growth factors at day 15 eventually led to constructs with better functional properties. Our findings suggest that economical tissue-engineering approaches can be developed to produce robust neocartilage through the combination of hydrodynamic bioreactor systems and shortened supplementation of exogenous growth factors. A similar beneficial effect on chondrocyte growth has previously been documented.19,20 In contrast to the current work demonstrating this transient effect under continuous fluid agitation, however, the study reported by Lima et al. indicated that the advantage of TGF-β3 removal vanished in neocartilage cultivation with continuous deformational loading.19 It was speculated that the application of dynamic compressive forces could retain two-to-three-fold greater concentrations of growth factors inside a construct than free swelling conditions27 such that the localized growth factors reached the level, where cellular catabolic activities were elicited.19 Such detrimental results were eliminated by delayed compressive stimuli applied after the termination of the TGF-β3 supply, suggesting that preconditioning of chondrocytes with growth factors can facilitate construct development during subsequent exposure to deformational loading.19 Although the contexts of culture systems, for example, type of growth factor, scaffolding material and loading condition and profile are quite different in Lima's and our studies, making direct comparisons challenging, these findings elucidate the complexity of mechanotransductive signaling that cells may introduce in response to various external mechanical stimuli and their loading protocols.

We further explored the kinetics of growth factor uptake/release by stimulated cells in relation to the duration of exposure to IGF-1 or TGF-β1. Diverse time-dependent trends were identified in IGF-1 (Fig. 3A, left) and TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B, left) cultures, indicating that the need for each growth factor in chondrocytes is governed by differential mechanisms. The final growth factor concentrations in waste media measured in all of the groups were higher than those added to fresh media, suggesting that chondrocytes possess the ability to secrete endogenous IGF-128,29 and TGF-β30,31 for self-supplementation such that their desire for exogenous growth factors gradually decreases. It has also been demonstrated that both IGF-1 and TGF-β are shear-responsive factors, meaning their expression and synthesis can be promoted by fluid shear stress.32,33 This evidence may account for the elevated concentrationsof IGF-1 and TGF-β1in culture media and implies the unnecessity of continuous addition of these two molecules to hydrodynamic cultures.

The modulation of growth factor secretion into the surroundings by supplementation protocols also altered the expression of the associated receptors, that is, IGF-1R and TGF-βRII. The IGF-1R levels in both transient and continuous IGF-1 samples decreased over time (Fig. 3C), while a similar decline in TGF-βRII was noticed in the continuous TGF-β1 group (Fig. 3D). It is believed that overdoses of growth factors can suppress expression of their own receptors34,35 possibly through enhanced receptor degradation.36 Futureinquiries into changes in receptor numbers due to their interactions with other environmental factors such as ECM37 are necessary. Besides, rapid IGF-1 accumulation in culture media (Fig. 3A) and evident IGF-1R downregulation in cells (Fig. 3C) may also result from the inclusion of ITS, which contains 10 μg/mL insulin, as part of medium supplements. Rationally, insulin and IGF-1 are highly similar in the molecular structure, both of which are capable of cross-reacting with the insulin receptor and IGF-1R.38,39 Although each receptor attracts its own ligand with a 100-to-1000-fold higher affinity than that to the other heterologous molecules,39 it is possible that insulin present in BMinterfered with the binding between IGF-1 and IGF-1R such that the disturbed expression of both molecules was observed. The dose of ITS (1%) employed here has previously been shown by our group to be essential to support the WWB cultivation of neocartilage in the presence of a minimal content of serum.18 Taken together, the suppressed influence of continuous exposure to IGF-1 or TGF-β1 on construct development can be attributed to massive growth factor leftovers in the environments, which elicit a negative feedback response that inhibits cellular expression of specific surface receptors and probably accelerates subsequent catabolic activities.19,40 Furthermore, transient exposure to IGF-1 or TGF-β1 is likely to maintain chondrocyte homeostasis, and thus promotes their anabolic functions under hydrodynamic stimuli.

A type I collagen-based fibrous capsule existed in IGF-1 and control constructs, but was eliminated by nourishment with TGF-β1 (Fig. 2C). Therefore, we further investigated the influence of the presence of the capsule on tissue homogeneity and focused on constructs transiently supplemented with growth factors that were shown to have better properties. Superior homogeneity was observed in the constructs without a capsule (TGF-β1-treated), whereas the IGF-1 inner cores exhibited significantly decreased type II collagen and GAG contents (Fig. 4A & 5A). This reduction is likely due to compromised collagen and GAG synthetic activities of cells occupying the IGF-1 inner cores (Fig. 4B & 5B). This evidence implies that the capsule composed of abundant cells may form a nutrient sink blocking cells in the interior of the construct from receiving medium supplements, which reduces their functionality. Noteworthily, the increased collagen I production by cells in the IGF-1 outer annuli may be organized into the formation of the fibrous capsule (Fig. 4C). Conversely, cells in TGF-β1 constructs demonstrated uniform potential for collagen deposition throughout the constructs and slightly better GAG synthesis in the inner cores of the constructs. This outcome is consistent with the findings reported by Kelly et al. who evaluated the radial variations of compressively loaded chondrocyte-laden agarose gels.41 Moreover, greater homogeneity yielded better mechanical strength owned byTGF-β1 constructs, which had a relatively strong inner core (Fig. 5C).

The capsule formation at the construct periphery is believed to result from the direct contact of chondrocytes with medium supplements that induce fibrotic processes.18,42 TGF-β is thought to be one of the molecules capable of facilitating fibrosis of different tissues and organs.42–44 A solid capsule is commonly recognized in cultures under hydrodynamic stimuli probably because chondrocytes located at the edge of constructs have a flattened, elongated shape, and thus become fibroblast-like6 such that more collagen I, but less GAG are produced.45,46 We also reported that sufficient fibrosis-promoting factors are necessary for the capsule formation even in hydrodynamic cultivation.18 However, the present study demonstrates that treatment with TGF-β1 eliminated the capsule in hydrodynamic constructs. One explanation is that elongated cells at the periphery of TGF-β1 constructs expressed a minimal level of TGF-βRII (Fig. 3D), the molecule associated with the initial binding of TGF-β and triggering subsequent intracellular reactions,35 so they were blocked from receiving TGF-β1 signals, and thus acted like normal chondrocytes. Supportively, a recent study showed that high doses of TGF-β (10 ng/mL) can suppress collagen I synthesis by fibroblasts via upregulation of CUX1.47 To further explain this observation, we investigated predominant cytoplasmic mediators in TGF-β signaling, among which, both Smad2 and Smad3 are receptor-regulated proteins and Smad7 is an inhibitory factor.48,49 We found that TGF-β1 or shear stress alone increased the phosphorylation of both Smad2 and Smad3 (Fig. 6A), leading to enhanced cartilage growth and capsule formation (Fig. 6B [statistical data of static cultures are available upon request]). Compared with stress alone, incorporation of TGF-β1 into the dynamic system amplified pSmad2 signals, but lowered pSmad3 intensity, yielding improved cartilage quality, but a reduced capsule structure. Evaluation of Smad7 indicated that the reduction in pSmad3was likely due to the direct action of Smad7 on Smad3 signaling in the early dynamic cultivation, but might be governed by other mechanisms in the later stage. In addition, discontinuation of TGF-β1 did not rescue the capsule in dynamic constructs, suggesting that this fibrotic process is irreversible. Previously, Brown et al. identified the diverse roles Smad2 and Smad3 play in epithelial cells and fibroblasts.50 We herein suggest that Smad2 and Smad3 primarily dominate chondrocyte- and fibroblast-specific phenotypes, respectively, in articular chondrocytes and both pathways are potently promoted by TGF-β or fluid shear stress. However, TGF-β reversely regulatesSmad2 and Smad3 signaling pathways in the presence of hydrodynamic stimuli partially through Smad7. Table 1 summarizes fluid shear/TGF-β-regulated Smad expression in relation to chondrocyte and cartilage development.

Table 1.

Summary of Potential Smad Regulation on Chondrocyte Activities in Response to Fluid Shear Stress and/or TGF-β1

| Culture conditions (control) | Extracellular stimulation | Intracellular regulation (versus control) | Cell/tissue responses (versus control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static | Fluid shear stressor TGF-β1 | pSmad2 ↑ pSmad3 ↑ |

Cartilage matrix ↑ Capsule formation ↑ |

| Hydrodynamic | TGF-β1 | pSmad2 ↑ pSmad3 ↓ Smad7*↑ |

Cartilage matrix ↑ Capsule formation ↓ |

Smad7 inhibits phosphorylation of Smad3 in the early development of tissue-engineered cartilage. ↑, enhanced synthesis; ↓, reduced synthesis.

TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1.

The present work demonstrates a cost-efficient tissue-engineering strategy for cartilage repair by combining transient exposure to exogenous growth factors with a hydrodynamic culture system. With this system, we identified a potential mechanism related to homeostasis between growth factor secretion and receptor expression to explain enhanced anabolic activities of chondrocytes cultured under transient stimulation of exogenous IGF-1 or TGF-β1. We also uncovered differential homogeneities of engineered constructs due to the presence of a fibrous capsule. Finally, we gained a preliminary understanding of chondrogenesis and fibrosis of chondrocytes governed by Smad2 and Smad3, respectively. Since the current study is limited to a single drug dose and one fluid agitation rate, future investigations are required to determine how varied combinations of growth factor concentration and shear stress magnitude impact the transient phenomenon, capsule formation, and Smad regulation. The strategy reported here holds promise for tissue-engineering applications that utilize allogeneic chondrocytes harvested from healthy young donors. These juvenile cells may be preferred because they are thought to possess a stronger ability to regenerate cartilage tissues51 and can be isolated without causing further damage to patients. Collectively, our findings provide valuable insights for controlling/engineering intracellular signals such as Smad to maximize chondrocyte-specific activities and minimize fibroblast-related behaviors to fabricate clinically relevant cartilage tissue replacements with a reduced fibrotic response and enhanced homogeneity.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation [NSF0602608].

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cheng Y.J. Hootman J.M. Murphy L.B. Langmaid G.A. Helmick C.G. Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2007 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darling E.M. Athanasiou K.A. Articular cartilage bioreactors and bioprocesses. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:9. doi: 10.1089/107632703762687492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia A.M. Lark M.W. Trippel S.B. Grodzinsky A.J. Transport of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 through cartilage: contributions of fluid flow and electrical migration. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:734. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia A.M. Frank E.H. Grimshaw P.E. Grodzinsky A.J. Contributions of fluid convection and electrical migration to transport in cartilage: relevance to loading. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;333:317. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou J.S. Mow V.C. Lai W.M. Holmes M.H. An analysis of the squeeze-film lubrication mechanism for articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1992;25:247. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90024-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vunjak-Novakovic G. Freed L.E. Biron R.J. Langer R. Effects of mixing on the composition and morphology of tissue-engineered cartilage. AIChE. 1996;J42:850. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vunjak-Novakovic G. Obradovic B. Martin I. Bursac P.M. Langer R. Freed L.E. Dynamic cell seeding of polymer scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:193. doi: 10.1021/bp970120j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooch K.J. Blunk T. Courter D.L. Sieminski A.L. Bursac P.M. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Freed L.E. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and mechanical environment interact to modulate engineered cartilage development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:909. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papoutsakis E.T. Fluid-mechanical damage of animal cells in bioreactors. Trends Biotechnol. 1991;9:427. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(91)90145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilgen B. Sucosky P. Neitzel P.G. Barabino G.A. Flow characterization of a wavy-walled bioreactor for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95:1009. doi: 10.1002/bit.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilgen B. Barabino G.A. Location of scaffolds in bioreactors modulates the hydrodynamic environment experienced by engineered tissues. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;98:282. doi: 10.1002/bit.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bueno E.M. Bilgen B. Carrier R.L. Barabino G.A. Increased rate of chondrocyte aggregation in a wavy-walled bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88:767. doi: 10.1002/bit.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bueno E.M. Laevsky G. Barabino G.A. Enhancing cell seeding of scaffolds in tissue engineering through manipulation of hydrodynamic parameters. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:516. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueno E.M. Bilgen B. Barabino G.A. Wavy-walled bioreactor supports increased cell proliferation and matrix deposition in engineered cartilage constructs. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1699. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bueno E.M. Bilgen B. Barabino G.A. Hydrodynamic parameters modulate biochemical, histological, and mechanical properties of engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:773. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilgen B. Uygun K. Bueno E.M. Sucosky P. Barabino G.A. Tissue growth modeling in a wavy-walled bioreactor. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:761. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedrich N. Haring R. Nauck M. Lüdemann J. Rosskopf D. Spilcke-Liss E. Felix S.B. Dörr M. Brabant G. Völzke H. Wallaschofski H. Mortality and serum nsulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and IGF binding protein 3 concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1732. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y.-H. Barabino G.A. Requirement for serum in medium supplemented with insulin-transferrin-selenium for hydrodynamic cultivation of engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2025. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima E.G. Bian L. Ng K.W. Mauck R.L. Byers B.A. Tuan R.S. Ateshian G.A. Hung C.T. The beneficial effect of delayed compressive loading on tissue-engineered cartilage constructs cultured with TGF-β3. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:1025. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers B.A. Mauck R.L. Chiang I.E. Tuan R.S. Transient exposure to transforming growth factor beta 3 under serum-free conditions enhances the biomechanical and biochemical maturation of tissue-engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1821. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang A.H. Stein A. Tuan R.S. Mauck R.L. Transient exposure to transforming growth factor beta 3 improves the mechanical properties of mesenchymal stem cell-laden cartilage constructs in a density-dependent manner. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3461. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim M. Erickson I.E. Choudhury M. Pleshko N. Mauck R.L. Transient exposure to TGF-β3 improves the functional chondrogenesis of MSC-laden hyaluronic acid hydrogels. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;11:92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauck R.L. Nicoll S.B. Seyhan S.L. Ateshian G.A. Hung C.T. Synergistic action of growth factors and dynamic loading for articular cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:597. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blunk T. Sieminski A.L. Gooch K.J. Courter D.L. Hollander A.P. Nahir A.M. Langer R. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Freed L.E. Differential effects of growth factors on tissue-engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:73. doi: 10.1089/107632702753503072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pei M. Seidel J. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Freed L.E. Growth factors for sequential cellular de- and re-differentiation in tissue engineering. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:149. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed L.E. Marquis J.C. Nohria A. Emmanual J. Mikos A.G. Langer R. Neocartilage formation in vitro and in vivo using cells cultured on synthetic biodegradable polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:11. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauck R.L. Hung C.T. Ateshian G.A. Modeling of neutral solute transport in a dynamically loaded porous permeable gel: implications for articular cartilage biosynthesis and tissue engineering. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:602. doi: 10.1115/1.1611512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlechter N.L. Russell S.M. Spencer E.M. Nicoll C.S. Evidence suggesting that the direct growth-promoting effect of growth hormone on cartilage in vivo is mediated by local production of somatomedin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clemmons D.R. Busby W.H. Garmong A. Schultz D.R. Howell D.S. Altman R.D. Karr R. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 proteolysis in articular cartilage and joint fluid results in enhanced concentrations of insulin-like growth factor 1 and is associated with improved osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:694. doi: 10.1002/art.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villiger P.M. Lotz M. Differential expression of TGF-β isoforms by human articular chondrocytes in response to growth factors. J Cell Physiol. 1992;151:318. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041510213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung W.-H. Lee K.-M. Fung K.-P. Lui P.P.-Y. Leung K.-S. TGF-β1 is the factor secreted by proliferative chondrocytes to inhibit neo-angiogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negishi M. Lu D. Zhang Y.-Q. Sawada Y. Sasaki T. Kayo T. Ando J. Izumi T. Kurabayashi M. Kojima I. Masuda H. Takeuchi T. Upregulatory expression of furin and transforming growth factor-β by fluid shear stress in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:785. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau K.-H.W. Kapur S. Kesavan C. Baylink D.J. Up-regulation of the Wnt, estrogen receptor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and bone morphogenetic protein pathways in C57BL/6J osteoblasts as opposed to C3H/HeJ osteoblasts in part contributes to the differential anabolic response to fluid shear. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krupp M. Lane M.D. On the mechanism of ligand-induced down-regulation of insulin receptor level in the liver cell. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebken J. Feydt A. Brinckmann J. Notbohm H. Muller P. Batge B. Ligand-induced downregulation of receptors for TGF-β in human osteoblast-like cells from adult donors. J Endocrinol. 1999;161:503. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1610503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosmakos F.C. Roth J. Insulin-induced loss of the insulin receptor in IM-9 lymphocytes. A biological process mediated through the insulin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:9860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeuchi Y. Nakayama K. Matsumoto T. Differentiation and cell surface expression of transforming growth factor-β receptors are regulated by interaction with matrix collagen in murine osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schumacher R. Mosthaf L. Schlessinger J. Brandenburg D. Ullrich A. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 binding specificity is determined by distinct regions of their cognate receptors. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dupont J. Khan J. Qu B.-H. Metzler P. Helman L. Leroith D. Insulin and IGF-1 induce different patterns of gene expression in mouse fibroblast NIH-3T3 cells: identification by cDNA microarray analysis. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4969. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morales T.I. Roberts A.B. Transforming growth factor beta regulates the metabolism of proteoglycans in bovine cartilage organ cultures. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly T.-A.N. Ng K.W. Ateshian G.A. Hung C.T. Analysis of radial variations in material properties and matrix composition of chondrocyte-seeded agarose hydrogel constructs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:73. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ignotz R.A. Massagué J. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobaczewski M. Bujak M. Li N. Gonzalez-Quesada C. Mendoza L.H. Wang X.-F. Frangogiannis N.G. Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107:418. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng X.M. Huang X.R. Chung A.C.K. Qin W. Shao X. Igarashi P. Ju W. Bottinger E.P. Lan H.Y. Smad2 protects against TGF-β/Ssmad3-mediated renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1477. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guh J.Y. Yang M.L. Yang Y.L. Chang C.C. Chuang L.Y. Captopril reverses high-glucose-induced growth effects on LLC-PK1 cells partly by decreasing transforming growth factor-beta receptor protein expressions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:1207. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V781207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darling E.M. Athanasiou K.A. Rapid phenotypic changes in passaged articular chondrocyte subpopulations. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:425. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fragiadaki M. Ikeda T. Witherden A. Mason R.M. Abraham D. Bou-Gharios G. High doses of TGF-β potently suppress type I collagen via the transcription factor CUX1. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1836. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi Y. Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Derynck R. Zhang Y.E. Smad-dependent and smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown K.A. Pietenpol J.A. Moses H.L. A tale of two proteins: differential roles and regulation of Smad2 and Smad3 in TGF-β signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran-Khanh N. Hoemann C.D. Mckee M.D. Henderson J.E. Buschmann M.D. Aged bovine chondrocytes display a diminished capacity to produce a collagen-rich, mechanically functional cartilage extracellular matrix. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1354. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.05.009.1100230617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]