Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to compare diet soda drinkers, regular soda drinkers, and individuals who do not regularly consume soda on clinically significant eating disorder psychopathology, including binge eating, overeating, and purging.

Method

Participants (n=2077) were adult community volunteers who completed an online survey that included the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire and questions regarding binge eating behaviors, purging, current weight status, and the type and frequency of soda beverages consumed.

Results

Diet soda drinkers (34%, n=706) reported significantly higher levels of eating, shape, and weight concerns than regular soda drinkers (22%, n=465), who in turn reported higher levels on these variables than non-soda drinkers (44%, n=906). Diet soda drinkers were more likely to report binge eating and purging than regular soda drinkers, who were more likely to report these behaviors than non-soda drinkers. Consumption of any soda was positively associated with higher BMI, though individuals who consumed regular soda reported significantly higher BMI than diet soda drinkers, who in turn reported higher weight than those who do not consume soda regularly.

Conclusions

Individuals who consume soda regularly reported higher BMI and more eating psychopathology than those who do not consume soda. These findings extend previous research demonstrating positive associations between soda consumption and weight.

Introduction

Obesity is a major public health concern in the United States (1). While a number of environmental and genetic factors have been identified as contributors to weight gain (1), sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) have been a recent focus of scrutiny because they represent the largest source of added sugars in the American diet (2). Recent estimates suggest that adults receive 5% to 8% of daily caloric intake from SSBs (3), and soda consumption alone rose 135% between 1977 and 2001 (4). Individuals who consume SSBs do not compensate for calories by reducing food intake (5), and a number of studies and reviews have shown that SSB consumption is associated with weight gain in children and adults (6-8).

The negative impact of SSB intake on health has lead to public health campaigns advocating for reduced consumption of SSBs and increased intake of non-caloric beverages (e.g., 9, 10). Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes have also been proposed in a number of cities and states in an attempt to reduce consumption (11). Replacement of caloric beverages with non-caloric options may be an important component of weight reduction (12). However, artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) may also pose some health risks. ASB consumption may dysregulate hunger cues and increase desire for sugary foods (13, 14). Furthermore, consumption of ASBs has also been associated with weight gain (14, 15) as well as higher risk for the development of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (16).

While previous research has examined the impact of SSBs and ASBs on weight and some diet-related diseases, few studies have investigated the relationship between SSB/ASB consumption and other forms of disordered eating. Therefore, this study aimed to compare diet soda drinkers, regular soda drinkers, and non-soda drinkers on several clinically significant variables related to disordered eating and weight. Based on previous research findings indicating SSBs/ASBs are associated with weight gain and can be associated with dysregulation of hunger cues, we predicted that (1) regular soda drinkers would have higher BMI levels than diet soda drinkers and non-soda drinkers; (2) diet soda drinkers would report higher levels of eating disorder psychopathology (such as shape and weight concerns) than regular soda drinkers and non-soda drinkers; and (3) diet soda drinkers would report more objective binge episodes and purging behaviors as compared to regular soda drinkers.

Method

Participants

Participants were 2077 community volunteers who responded to an online advertisement about a study relating to eating and health behaviors. Craigslist advertisements for the online study were posted in various cities in the United States. Participants completed several self-report questionnaires through the secure online survey software website SurveyMonkey after providing informed consent. The study was approved by Yale University’s institutional review board. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was: 77.6% white, 6.3% Hispanic, 5.8% Asian, 5.8% African American, and 4.5% other or missing data. The mean BMI was 30.78 kg/m2 (sd = 9.2) and mean age was 34.4 years (sd = 12.0).

Assessments and Measures

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (17) is the self-report version of the Eating Disorder Examination interview (18) and assesses eating disorder features including objective and subjective binge episodes and purging behaviors, and produces dietary restraint, and eating, shape, and weight concern subscales. The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire has received psychometric support, including adequate test-retest reliability (19), and strong convergence with the Eating Disorder Examination interview (20, 21).

Self-reported data were collected on type and frequency of beverages consumed, height, current weight, and demographics. Beverage consumption questions were: (1) “What type of soda do you usually drink?” and the response options were diet and regular; and (2) “How many sodas do you drink per day?” and response options asked participants to indicate the number of 12 ounce cans, 20 ounce bottles, and 2-liter bottles. If the participant indicated they consumed zero servings of soda per day, they were categorized as a non-soda drinker.

Statistical Analyses

ANOVAs and chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether soda groups differed on demographic variables. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine whether clinically relevant variables differed among adults who report consuming diet soda, regular soda, and no soda on a daily basis. Follow-up ANOVAs examined whether the soda groups differed on Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire subscale scores, frequency of binge eating, purging, and overeating episodes, and BMI. Chi-square tests examined whether soda groups differed on the presence of clinically significant binge eating or purging. Finally, a series of ANCOVAs was conducted to control for age, gender, and race. All analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (SPSS 19, Chicago, IL) and were based on a .05 significance level.

Results

Approximately one-third of the sample (34.0%, n=706) indicated they consumed diet soda,22.4% (n=465) indicated they consumed regular soda, and 43.6% (n=906) of individuals indicated they do not consume soda. On average, soda drinkers reported consuming 34.0 (sd=40.8) ounces of soda daily, or nearly three 12-ounce cans of soda per day.

Psychological and Behavioral Features Associated with Soda Consumption

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the participants within the soda consumption groups. Diet soda drinkers were significantly older than regular soda drinkers. Women were more likely than men to consume diet soda, while men were more likely than women to report consuming regular soda. African American participants were more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to consume regular soda, Caucasian groups were more likely to consume diet soda, and Asian participants were more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to report they did not consume soda on a regular basis.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Regular Soda (n=465) | Diet Soda (n=706) | No Soda (n=906) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | ||

| Agea | 33.4 | 10.9 | 35.4 | 12.0 | 34.2 | 12.4 | 3.5 | .03 | |

| χ2 | p | ||||||||

| Gender | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | 22.0 | <.001 | ||||

| Male | 33.6 (89) | 30.2 (80) | 36.2 (96) | ||||||

| Female | 20.8 (375) | 34.6 (625) | 44.6 (806) | ||||||

| Race | 67.8 | <.001 | |||||||

| White | 19.6 (334) | 36.8 (626) | 43.6 (745) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 32.9 (46) | 27.9 (39) | 39.3 (55) | ||||||

| African American | 44.4 (60) | 14.8 (20) | 40.7 (55) | ||||||

| Asian | 25.2 (33) | 29.7 (35) | 48.1 (63) | ||||||

Scheffe post-hoc test: Significant difference between diet soda and regular soda

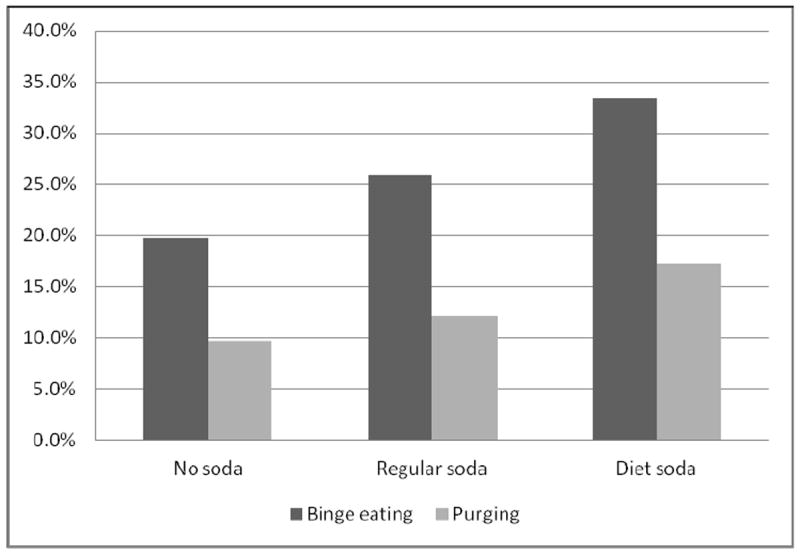

Diet soda drinkers, regular soda drinkers, and individuals who do not consume soda were compared on a number of psychological and behavioral variables associated with disordered eating. The MANOVA comparing soda type on clinical variables (i.e., EDEQ subscales and eating and purging episodes) was highly significant (F (14, 4096) = 11.21, p = <.001; Wilks’ Lambda = 0.928). Follow-up ANOVAs indicated significant group differences on all clinically relevant variables. Table 2 presents results of these univariate comparisons and Scheffe post-hoc analyses. Because the homogeneity of variances assumption was violated, the Welch-Swattherwaite test is reported. ANCOVAs were conducted to control for age, gender, and race. The pattern of group differences persisted after controlling for demographic variables. Regular soda drinkers also had significantly higher BMI than diet soda drinkers, and diet soda drinkers had significantly higher BMI than individuals who reported consuming no soda. In regards to the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire subscales, diet soda drinkers reported higher levels of dietary restraint, and higher eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns than both regular soda drinkers and those who do not consume soda. Furthermore, regular soda drinkers reported higher eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns than participants who do not consume soda. Diet soda drinkers reported more frequent objective binge episodes and objective overeating episodes during the past 28 days than both regular soda drinkers and those who reported not consuming soda. Finally, we examined whether rates of clinically significant binge eating and purging – defined as reporting binge eating or purging at a frequency of once per week or more – differed across soda groups. This frequency threshold for determining clinical significance corresponds with DSM-5 frequency thresholds for the diagnoses of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (22, 23). Diet soda drinkers were significantly more likely to report clinically significant binge eating (χ2 (2, n=2072) = 37.8, p<.001) and purging (χ2 (2, n=2072) = 21.1, p<.001) than were the regular soda and non-soda drinkers.

Table 2.

Psychological and behavioral characteristics of participants

| Regular Soda (n=465) | Diet Soda (n=706) | No Soda (n=906) | ANOVA | ANCOVA1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | df | F | P | η2 | F | p | ηp2 | |

| BMIabc | 33.8 | 10.6 | 31.4 | 9.0 | 28.7 | 8.0 | 2069 | 52.6 | .000 | .048 | 42.4 | .000 | .045 |

| Soda ounces per dayabc | 36.2 | 55.3 | 32.6 | 29.4 | 0 | 0 | 2055 | 305.4 | .000 | .229 | 258.1 | .000 | .226 |

| EDE-Q2 | |||||||||||||

| Dietary Restraint abc | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2074 | 36.9 | .000 | .034 | 35.0 | .000 | .038 |

| Eating Concern ac | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2074 | 33.3 | .000 | .031 | 30.7 | .000 | .033 |

| Weight Concern abc | 3.3 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 2074 | 32.5 | .000 | .030 | 28.7 | .000 | .031 |

| Shape Concern abc | 3.9 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 2074 | 31.5 | .000 | .029 | 27.2 | .000 | .030 |

| # Objective Binge ac Episodes within the past month | 2.7 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 2062 | 14.8 | .000 | .014 | 10.9 | .000 | .012 |

| # Subjective Binge c Episodes within the past month | 2.6 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 2069 | 5.3 | .005 | .005 | 2.9 | .055 | .003 |

| # Overeating episodes a,c with the past month | 3.5 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 2066 | 9.6 | .000 | .009 | 7.0 | .001 | .008 |

| # purges within the past c month | 2.1 | 7.4 | 3.4 | 10.1 | 2.0 | 9.4 | 2067 | 4.6 | .010 | .004 | 5.1 | .006 | .006 |

ANCOVA controlling for race, gender, and age.

Eating Disorder Examination - Questionnaire

Scheffe post-hoc test: Significant difference between diet soda and regular soda

Scheffe post-hoc test: Significant difference between regular soda and no soda

Scheffe post-hoc test: Significant difference between diet soda and no soda

Figure 1 displays the rates of clinically significant (i.e., >= once weekly) binge eating and purging within soda groups.

Figure 1.

Rates of clinically significant binge eating and purging within soda groups.

Discussion

Results indicated that diet soda drinkers reported significantly more binge episodes, purging behaviors, higher levels of eating restraint, and higher concerns about body shape, weight, and eating as compared to the regular soda drinkers and non-soda drinkers. However, BMI was significantly higher among regular soda drinkers as compared to diet soda drinkers and those who do not consume soda. These results offer additional support for previous research indicating a positive relationship between BMI and consumption of SSBs (5-7). Furthermore, our findings contribute to the existing body of research indicating that both ASBs and SSBs have negative impact on health. Though research has focused on beverage consumption and the impact on weight and some diet-related diseases, this study specifically examined the relationship between consumption of ASBs/SSBs and characteristics associated with eating disorders.

The study is strengthened by the large sample size that was recruited from a range of cities in the United States and the use of validated measures to assess behavioral and psychological variables associated with disordered eating behaviors. There are several limitations to this study. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevents drawing conclusions about causality. Furthermore, the data on soda consumption and BMI were all self-reported. Another possible limitation is the use of a convenience sample drawn from internet volunteers. However, perceived anonymity has been shown to produce more candid responses regarding eating pathology (24), suggesting the method of data collection (i.e., questionnaires presented over the internet to anonymous volunteers) may also serve as a strength of this study.

Future studies should investigate the relationship between other SSBs/ASBs, binge eating behaviors, and associated psychological characteristics. Longitudinal investigations would permit analysis of specific health risks associated with beverage selection and consumption patterns. Such investigations would provide additional data on the potential adverse health effects associated with soda consumption, including high BMI and compensatory behaviours, and possible long-term complications such as Type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

M. A. Bragg originated the study idea, helped with the design data analysis, and led the writing. M. A. White acquired the data, assisted with the design and data analysis, and provided critical feedback on drafts of the manuscript.

Biographies

Marie Bragg, MS, MPhil, is a doctoral student at Yale University pursuing a degree in Clinical Psychology. Her current research focuses on how professional athletes and sports organizations are used to promote unhealthy foods and beverages.

Marney A. White, Ph.D., M.S. is a clinical psychologist and an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and of Epidemiology and Public Health (Chronic Diseases) at the Yale University School of Medicine. Her research focuses on binge eating disorder and the interaction of cigarette smoking with eating disorder symptomatology and weight problems.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation. [June 1, 2012];2012 Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Accelerating-Progress-in-Obesity-Prevention.aspx.

- 2.Guthrie JF, Morton JF. Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:43–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Park S. Consumption of Sugar Drinks in the United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011 Aug;71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swithers SE, Davidson TL. A role for sweet taste: calorie predictive relations in energy regulation by rats. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:161–173. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–08. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu Frank B. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:667–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scaperotti J, De Leon C. New Campaign Asks Yonkers if They’re “Pouring on the Pounds”. [June 2012];2009 Aug 31; Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2009/pr057-09.shtml.

- 10. [June 2012];Kick the Can home page. Available at: http://www.kickthecan.info/

- 11.Strum R, Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Soda Taxes, Soft Drink Consumption, And Children’s Body Mass Index. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):1052–1058. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laska MN, Murray DM, Lytle LA, Harnack LJ. Longitudinal Associations Between Key Dietary Behaviors and Weight Gain Over Time: Transitions Through the Adolescent Years. Obesity. 2012;201:118–125. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson TL, Swithers SE. A Pavlovian approach to the problem of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:933–935. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler SP, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hunt KJ, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. Fueling the Obesity Epidemic? Artificially Sweetened Beverage Use and Long-term Weight Gain. Obesity. 2008;16:1894–1900. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Wang Y, Lima JA, Michos ED, Jacobs DR. Diet Soda Intake and Risk of Incident Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Diabetes Care. 2009;32:688–694. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn C, Wilson T. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. Eating Disorder Examination; pp. 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Self-Report Questionnaire Version (EDE-Q) Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:349–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<349::aid-eat15>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. [July 2012];Proposed revisions: Bulimia Nervosa. (5). 2012 Apr 17; Available at: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=25.

- 23.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. [July 2012];Proposed revisions: Binge eating disorder. (5). 2012 Apr 17; Available at: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=372.

- 24.Lavender JM, Anderson DA. Effect of perceived anonymity in assessments of eating disordered behaviors and attitudes. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:546–551. doi: 10.1002/eat.20645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]