Introduction

The UK’s Conservative-led coalition came to power promising to shrink the deficit that rapidly increased due to bank-sector bailouts and falling tax revenues. It pursued this by a combination of tax rises (15% of the total austerity package) and spending cuts (85%),1 reducing expenditure by £85 billion from April 2010.2 Capital spending has been slashed and many public sector workers have lost their jobs; those still employed have experienced wage freezes. Despite these sweeping measures, the most recent budget estimates from the Office for Budget Responsibility2 show that the deficit rose from £121.0 billion in 2011/2012 to £123.2 billion in 2012/2013 (excluding the statistical artefact arising from the public sector absorption of Royal Mail’s pension assets in 2012). A major factor has been the failure to achieve economic growth (Web Appendix 1).

There is little disagreement that the government has failed to achieve its stated goals of economic recovery and debt reduction. But why? Is it because austerity was a mistake and increased spending was necessary? This view is held by many leading economists, such as Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz and David Blanchflower. They note how President Obama’s US$831 billion stimulus package has yielded a much faster recovery than the UK’s austerity measures. They have been joined by former advocates of austerity, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The Fund now acknowledges that ‘we underestimated the negative effect of austerity on jobs and spending power’, instead calling for public stimulus.3,4

Yet, other economic commentators interpret the data as warranting more austerity.5 They see failure reflecting too little of the austerity needed to spur market confidence and private sector investment. Two prominent economists have argued for ‘expansionary austerity’, claiming ‘austerity based on appropriate spending cuts is the best way to reduce a country’s public debt burden.’6 Another study that had underpinned the case for austerity has now been found to have contained simple mistakes in a spreadsheet and in fact shows the opposite.5 Those holding this view note that UK government spending, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), has actually risen, from 37.4% in 2007/2008 to 42.6% in 2009/2010 under the Labour government, then falling to a lower, yet elevated, level of 42.2% in 2012/2013 under the coalition. Thus, Jon Moulton, a venture capitalist and frequent media commentator, claims ‘it would have been better if the government had cut public spending harder and deeper at the start of Parliament and forced a large private sector to emerge’ and that the ‘UK needs an emergency budget full of shocks.’7,8 The journalist Peter Oborne writes that ‘Mr Osborne has talked of austerity ever since his “emergency Budget” almost three years ago. But at no stage has he delivered it, or anything like it.’8 Whichever view is correct, there is a seeming paradox: a government pursuing a policy of austerity is increasing its debt and deficit.9

One neglected aspect of the debate is on austerity’s health effects. If the economists cannot agree what to do, then the public health community should call attention to the health consequences of the alternatives and ensure that they are taken into account by our political representatives. To do so, we first ask what has actually happened to different types of government spending in the UK and the rest of Europe. We use comparable budgetary data between 2009 and 2011 from 25 EU countries taken from EuroStat’s Government Expenditure Dataset 2013 edition. We disaggregate expenditure by major budget sectors, such as health, education and defence, as well as areas of social protection, including housing, old-age pensions and social exclusion (a specific EU category relating to excluded minorities such as the Roma) (Web Appendixes 2 and 3). In order to compare the UK with the rest of Europe, monetary units were adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity.

UK austerity package is third largest in Europe

First, we examined spending cuts. Between 2009 and 2011, the UK’s public expenditure was cut by 2.2%, or about £245 per capita. Thus, the UK’s austerity package ranks the third largest in Europe, behind the larger real spending declines in Greece and Luxembourg. By contrast, Sweden, Poland and Germany substantially increased government spending in the 2009–2011 period.

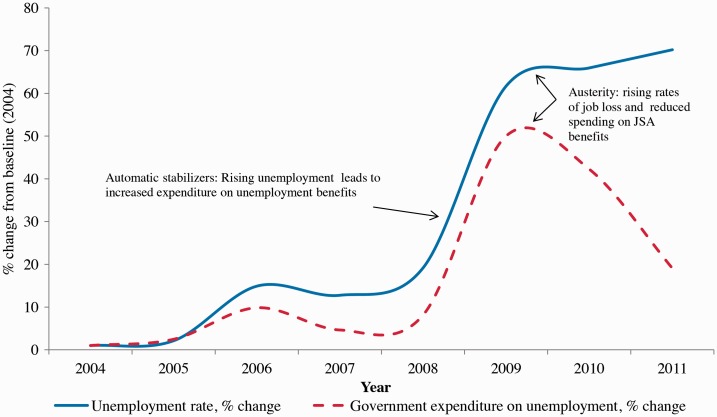

These data seem at odds with the figures showing growing public expenditure as a percentage of GDP, often cited by the advocates of greater austerity. However, expenditure as a percentage of GDP is misleading, because GDP (the denominator) has itself fallen, inflating the fraction of spending as a percentage of GDP. Additionally, had the government not pursued austerity policies, spending as a percentage of GDP would have risen even more because of the existence of ‘automatic stabilizers’ – an automatic rise in overall spending when more people qualify for unemployment benefits and poverty relief during recession (and vice versa when the economy recovers). These stabilizers are so-named because they act counter-cyclically to minimize fluctuations in real GDP. To illustrate this point, Figure 1 depicts actual unemployment rates versus spending on unemployment benefits in the UK. Those persons becoming unemployed normally qualify for unemployment benefits, leading spending to rise in parallel. However, as the figure shows, the recent budget cuts have broken this historical trend. At a time of elevated unemployment, there were substantial declines in unemployment benefits per capita, as spending failed to keep pace with increasing need.

Figure 1.

Change in social protection expenditure on unemployment and the unemployment rate (%), UK, 2004–2011. Expenditure on unemployment benefit is adjusted for inflation and purchasing power.

In summary, some of the statistics being used to justify greater austerity are simply misleading.

Austerity is disproportionately affecting persons with disabilities and the unemployed

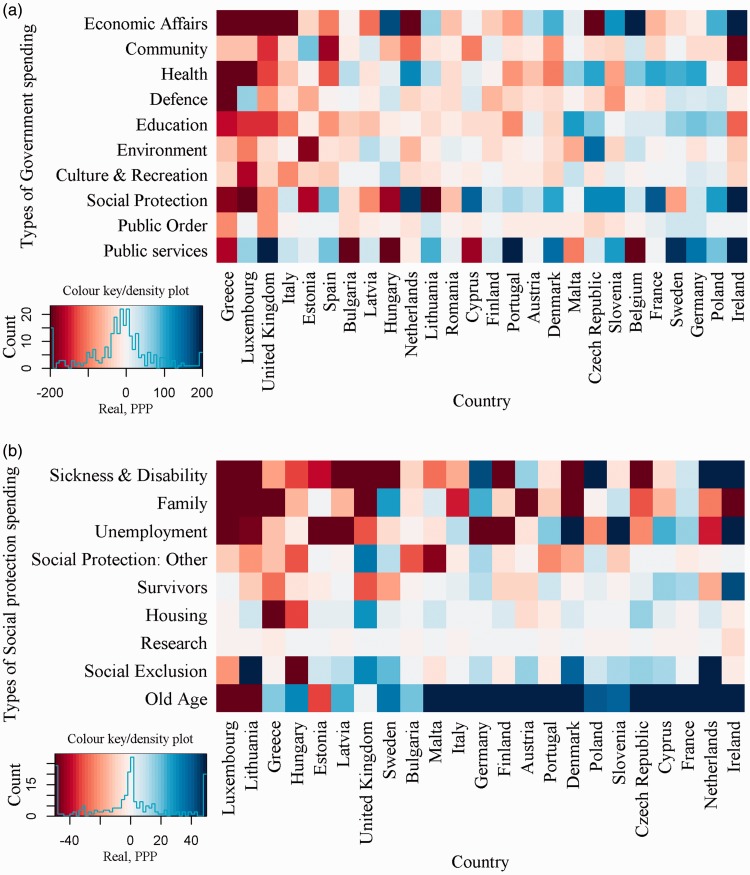

To assess which groups were most adversely affected by austerity measures, Figure 2(a) depicts the changes in each major component of government spending across Europe. The UK experienced reductions in almost all areas of government spending, except for foreign aid and interest payments on public debt (Web Appendix 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Total austerity packages by type of government spending, 26 EU countries, 2009–2011. Heatmap depicts reductions in sector-specific government expenditure (constant, purchasing power parity, per capita) across country-specific austerity period for which data are available. Types of government spending ordered from greatest cuts (in red, e.g. economic affairs) to lowest cuts (in blue, e.g. public services) overall. (b). Budget cuts to Social Protection Systems, 23 EU countries, 2009–2011. Heatmap depicts reductions in sector-specific government expenditure (constant, purchasing power parity, per capita) across country-specific austerity period for which data are available. Types of social spending ordered from greatest cuts (in red, e.g. sickness and disability benefits) to lowest cuts (in blue, e.g. old-age pensions) overall. Twenty-three countries are provided for which data are available.

Ten European countries reduced spending on social protection during the economic downturn (Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Romania, Sweden and the United Kingdom) and 17 increased it. Health budgets tend to have the largest reductions, followed by housing and community funds (apart from ‘economic affairs’, which artefactually fell after massive bank bailouts packages of 2008, see Figure 2(a)). Although the UK government promised to protect health spending, real expenditure on the National Health Service (NHS) in 2012/2013 fell by approximately 3.5%, partly because the NHS handed back a £2.2 billion underspend in 2012/2013.10

Figure 2(b) shows the effect of austerity on different social protection programmes. Between 2009 and 2011, the UK increased spending slightly in three areas: Social Exclusion (mainly comprising Child and Working Tax Credits), Housing (increased numbers of persons at risk of homelessness) and Pensions (with population ageing). By contrast, spending in all other categories was reduced. These included average annual reductions of £22 per person in sickness and disability benefits, £28 per person in family support (including early childhood development programmes), and approximately £18 per person in unemployment benefits. Across Europe, declining sickness and disability benefits contributed most to overall budget cuts, followed by family support (including early childhood development programmes) and unemployment benefits.

As these findings demonstrate, governments faced with a financial crisis have choices. The UK government has chosen to cut social protection while others have not.

Current and future effects of austerity on health in the UK

While it is too early to see the full effects of austerity, two reports from the Institute of Health Equity and WHO indicate that austerity is likely to widen health inequalities.11,12 UK budget cuts are concentrated in the most deprived UK regions, where premature mortality is greater.13 Two main channels operate: (i) direct effect through cutting effective prevention and treatment programmes; and (ii) indirect effects of increasing unemployment, poverty, and homelessness and other socioeconomic risk factors, while cutting effective social protection programmes that mitigate their risks to health. Here, we describe UK examples of the latter indirect mechanisms, noting that the former, access to healthcare, is being reduced to a greater extent elsewhere in Europe.14

First, a key goal of austerity is to reduce public-sector employment; resulting job loss can be expected to increase depression and suicide rates.12 Between 2007 and 2009, suicides rose across the UK as unemployment increased. Between 2009 and 2010, the suicide rate declined temporarily, increasing again in 2011. According to the Office of National Statistics, there were over 500,000 public sector job losses between June 2010 and September 2012, of which over 35% were in the North of England (North-East, North-West and Yorkshire and the Humber).15 A total of 36,000 NHS jobs were cut in this period, costing over £435 million in severance packages; in total, a further 144,000 public-sector redundancies are expected in 2015–2016. The regional pattern of job losses correlates with suicide changes16; a 20% rise was observed in those regions most affected by austerity: the North-East, the North-West, and Yorkshire and the Humber, but a decline in London, where unemployment fell.13

Second, replacing the Disability Living Allowance with Personal Independence Payments will likely adversely impact people with disabilities. Imposition of a 12-month time limit on non-means-tested disability benefits (for those in the Work-Related Activity Group) will reduce payments by up to £4212 per year for approximately 280,000 persons; about 150,000 of persons living with disabilities currently live in poverty, and an estimated additional 50,000 adults are estimated to be at risk of poverty due to these cuts.17 The numbers eligible for benefits will be reduced as a result of tighter ‘fitness for work’ criteria, such as redefining those able to walk to include those who can manage 20 metres, rather than 50 previously.

Finally, cuts to the social housing budget and income support are coinciding with marked rises in homelessness.12 Under the Labour Government, homelessness was declining (see Web Appendix 4). The coalition government cut housing benefits by 10% for some groups and has capped housing allowances. UK homelessness trends have since reversed, increasing by over 40% (about 10,000 additional families). These large rises occur despite the coalition adopting a more stringent re-definition of homelessness which likely understates the increase. Rises appear concentrated where rents were already high, such as the East and South East (>30%), while numbers continued to decline in some areas of the North.

In summary, austerity policies can be expected to impact health in several ways, each difficult to reverse or avoid in the absence of strong social safety nets.11,18

Whither austerity?

In the UK, as with most of Europe, the burden of budget cuts is falling most greatly on disabled, low-income and unemployed persons. The government has argued that there is no alternative to austerity. Yet, several countries have averted deep budget cuts. There is no evidence that their economies have suffered as a result; indeed, ‘stimulus countries’ have benefited (see Web Appendix 1).

Historic evidence indicates the existence of viable alternatives to austerity. In the years immediately following the World War II, when the UK national debt exceeded 200% of GDP, the Labour Government created the modern welfare state. In 1948, it established the NHS and introduced family allowances, the precursor to universal child benefit. Public debt fell from its peak of 237.94% of GDP in 1947 to 131.1% a decade later. The little money available was invested in rebuilding infrastructure, health and education systems. It paved the way for healthier and more productive communities, leading to three decades of prosperity. Similarly, both the New Deal in the US and the Marshall Plan in Germany show that smart investment approaches can succeed times of hardship.19

Today, the politics of debt has been the polar opposite: an attack on universalism and the welfare state.20 Universal child benefit is now means-tested. Affordable higher education has been ended with large rises in tuition fees. Rather than investing in the engines of economic growth – health, education, public infrastructure and social protection – the sectors that helped spur recovery after World War II, the coalition government is pursuing further cuts.9 Yet, the counter-examples are not only historical; a contemporary one is Iceland’s rejection of austerity following a referendum.19 Although, as we note above, the intellectual foundations of austerity as an economic response to crises have been questioned, the evidence of its risks to health should be enough to give us pause.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This study was carried out with financial support from the Commission of the European Communities, Grant Agreement no. 278511. The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission’s views and in no way anticipates the Commission’s future policy in this area

Guarantor

AR

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Contributorship

AR, DS and MM conceived the analysis; AR and DS gathered the data and conducted the analysis, and wrote the first draft; AR, DS, MM and SB contributed to the writing of the paper

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation for the helpful comments from the reviewer.

Provenance

Submitted; peer-reviewed by Danny Dorling

References

- 1.Johnson P. Spending Review – Opening Remarks [June 2013], London: IFS, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office for Budget Responsibility Economic and Fiscal Outlook: March 2013, London: OBR, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3. thinkSPAIN. IMF: We underestimated the negative effects of austerity on unemployment and spending power. thinkSPAIN, 6 January 2013.

- 4.International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth, Washington, DC: IMF, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinhart CM, Rogoff KS. Growth in a time of debt. Am Econ Rev 2010; 100: 573–8 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alesina A, de Rugy V. There is Good and Bad Austerity, and Italy Chose Bad, New York, NY: Forbes Publishing, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moulton J. We're paying the price for not cutting harder. The Times, 21 March 2013.

- 8. Oborne P. Budget 2013: Labour made the mess, but the Tories are only making it worse. The Daily Telegraph, 20 March 2013.

- 9.Reeves A, Basu S, McKee M, Meissner C, Stuckler D. Does investment in the health sector promote or inhibit economic growth? Globalization & Health. in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HM Treasury. Budget 2013, London: The Stationery Office, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health 2012; 126(Suppl 1): S4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UCL Institute of Health Equity The Impact of the Economic Downturn and Policy Changes on Health Inequalities in London, London: UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor-Robinson D, Gosling R. Local authority budget cuts and health inequalities. BMJ 2011; 342: 564–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011; 378: 1457–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ONS Public Sector Employment, Q3 2012, London: ONS, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ 2012; 345: 13–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department for Work and Pensions Time limit contributory Employment and Support Allowance to one year for those in the Work-Related Activity Group: Impact Assessment, London: DWP, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012; 380: 1011–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuckler D, Basu S. The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills, London: Penguin, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKee M, Stuckler D. The assault on universalism: how to destroy the welfare state. BMJ 2011; 343: d7973–d7973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]