Abstract

Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) is an important therapeutic target for treatment of pulmonary diseases. Previously, we identified novel N-benzoylindazole derivatives as potent, competitive, and pseudoirreversible HNE inhibitors. Here, we report further development of these inhibitors with improved potency, protease selectivity, and stability compared to our previous leads. Introduction of a variety of substituents at position 5 of the indazole resulted in the potent inhibitor 20f (IC50~10 nM), and modifications at position 3 resulted the most potent compound in this series, the 3-CN derivative 5b (IC50= 7 nM); both derivatives demonstrated good stability and specificity for HNE versus other serine proteases.

Molecular docking of selected N-benzoylindazoles into the HNE binding domain suggested that inhibitory activity depended on geometry of the ligand-enzyme complexes. Indeed, the ability of a ligand to form a Michaelis complex and favorable conditions for proton transfer between Hys57, Asp102 and Ser195 both affected activity.

Keywords: indazole, human neutrophil elastase, elastase inhibitor, inhibitor selectivity, molecular docking

Introduction

Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) is a member of the chymotrypsin superfamily of serine proteases involved in the response to inflammatory stimuli.1,2 HNE is stored in azurophilic granules of neutrophils and is very aggressive and cytotoxic, as its substrates include many components of the extracellular matrix.3 Due to the destructive potency of HNE, its extracellular activity is regulated under physiological conditions by endogenous inhibitors, such as α1-proteinase inhibitor (α1-PI) and α2-macroglobulin.4,5 When the appropriate balance between HNE and its inhibitors fails in favour of the protease, the excess HNE activity may lead to tissue damage and the consequent development of a variety of diseases. Among the pathologies associated with increased HNE activity are acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),6 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),7,8 cystic fibrosis (CF),8 and other disorders with an inflammatory component, such as atherosclerosis, psoriasis, and dermatitis.10-14 Recently HNE has also been implicated in the progression of non-small cell lung cancer progression.15 Thus, a number of clinical observations indicate that HNE represents a good therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and might be of value as therapeutic agents in lung cancer.15-20

The design of new HNE inhibitors has focused primarily on the development of different inhibitor-types, including mechanism-based inhibitors, acylating-enzyme inhibitors, transition-state analogs, and non-covalent inhibitors.16-20 Despite the large number of HNE inhibitors described in the literature, Sivelestat is the only non-peptidic inhibitor marketed, and it is limited to use in Japan and Korea for the treatment of acute lung injury, since its development in the USA was terminated in 2003.21,22 On the other hand, the neutrophil elastase inhibitor AZD9668 is currently being evaluated in clinical trials for patients with bronchiectasis and COPD.23,24

Recently, we discovered that N-benzoylpyrazoles and N-benzoylindazoles are potent HNE inhibitors25-27. In the present studies, we further optimize HNE inhibitors with an N-benzoylindazole scaffold and evaluate their biological activity. Introduction of a variety of substituents at the phenyl ring of the indazole nucleus and elaboration of the ester function at position 3 demonstrated that the cyclic amides, as well as the benzoyl fragment at position 1, are essential for activity. Studies on the most active derivatives, which were active in the low nanomolar range, showed that these compounds are competitive, pseudoirreversible inhibitors of HNE, with an appreciable selectivity towards HNE versus other kinases tested. We also utilized molecular modeling to evaluate binding of the compounds to the HNE active site and determined that both the ability of an inhibitor to form a Michaelis complex and favorable conditions for proton transfer between His57, Asp102, and Ser195 affected inhibitory activity. Thus, the N-benzoylindazole scaffold has great potential for the development of additional potent HNE inhibitors.

Chemistry

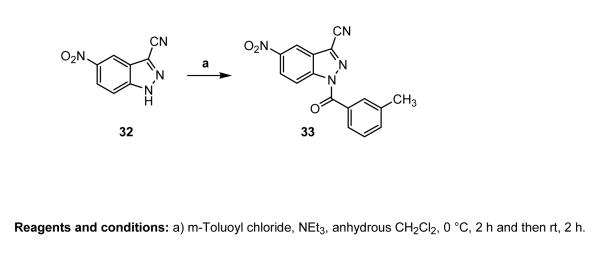

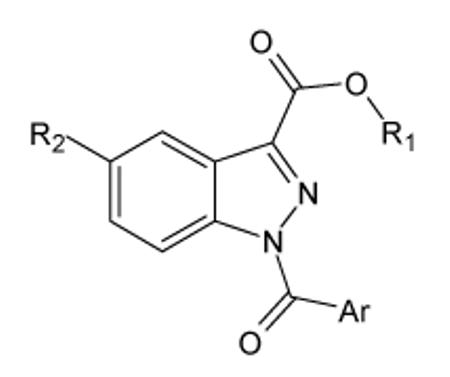

All final compounds were synthesized as reported in Schemes 1-6 and the structures were confirmed on the basis of analytical and spectral data. The synthetic pathway leading to the final benzoyl-1H-indazoles 5a-e and 8, which are substituted at position 3 of the indazole, is depicted in Scheme 1. Compounds 5a-d were obtained starting from the previously described precursors 3 and 4,28,29 following two different procedures: treatment with the appropriate benzoylchloride and Et3N in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5a-c) or treatment with m-toluic acid, Et3N, and ethyl cloroformate in anhydrous THF (5d). For synthesis of 5e, the (1H-indazol-3-yl)-methanol 130 was transformed into the ester derivative 2, which was treated with m-toluoyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 to obtain the final compound. The same precursor 130 was also used for the synthesis of compound 8. First, it was necessary to protect the alcohol function at position 3 with 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran (compound 6), followed by insertion of the benzoyl fragment at N-1, and finally removal of the protecting group with trifluoroacetic acid.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 6.

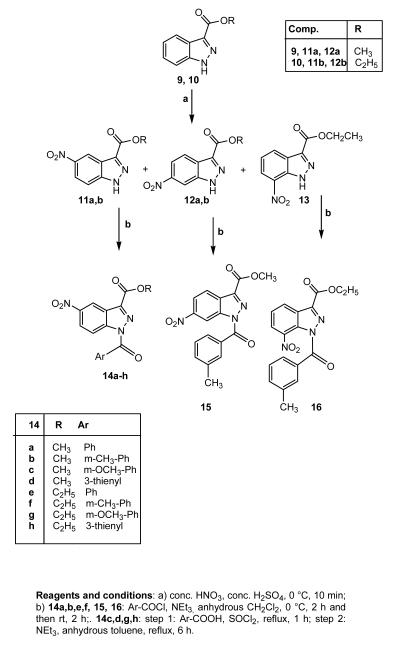

Scheme 2 shows the synthetic routes followed to obtain nitro-derivatives 14a-h (14e31), 15, and 16. Treatment of compounds 932 and 1031 with H2SO4/HNO3 1:1 v/v at 0 °C resulted in a mixture of the intermediates 11a,b,32 12a,b (12a33), and 1334 in different yields (60% for 11a,b, 10% for 12a,b and 5% for 13), which were separated by column chromatography and subsequently transformed into the final compounds 14a h, 15, and 16 following the same procedures, as described previously.

Scheme 2.

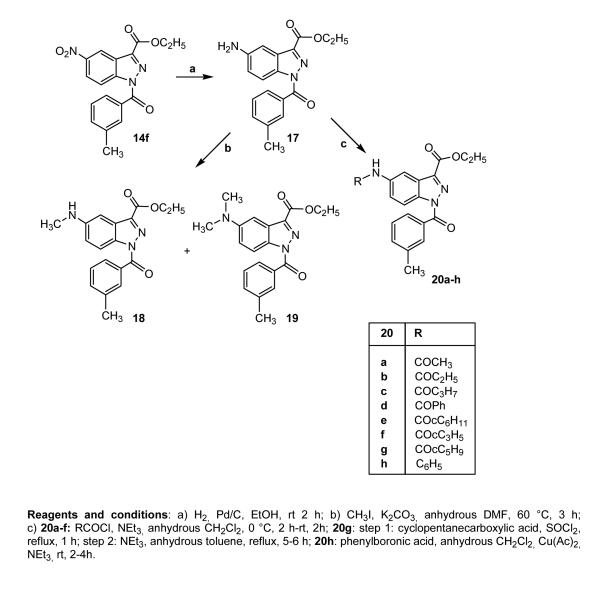

The 5-amino and 5-alkyl(aryl)amido derivatives 18, 19, and 20a-h were obtained starting from a common precursor, the 5-NO2 derivative 14f described above, which was transformed into the corresponding 5-amino 17 through catalytic reduction with a Parr instrument. Treatment of 17 with iodomethane, (cyclo)alkylcarbonyl chloride, or phenylboronic acid resulted in the final compounds 18, 19, 20a-g, and 20h, respectively.

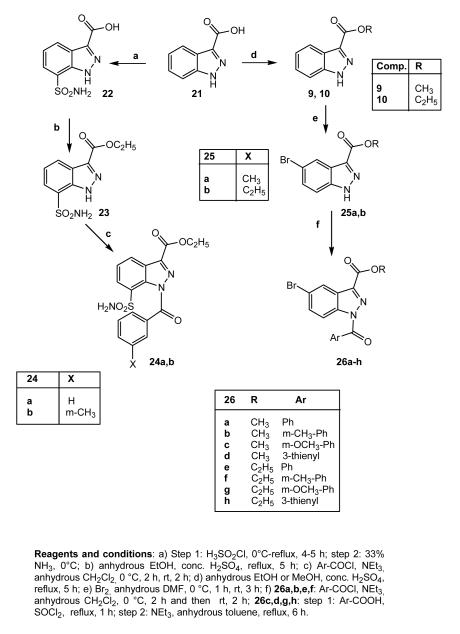

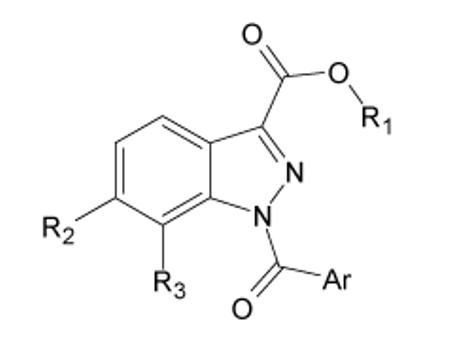

In Scheme 4, the synthetic pathways leading to the 7-sulfamoyl (24a,b) and 5-bromo (26a-h, 26e32) indazole derivatives are shown. Introduction of the sulfamoyl moiety was carried out by treatment of the commercially available 21 with chlorosulfonic acid and 33% aqueous ammonia (22). Esterification of 22 and further insertion of the benzoyl fragment resulted in the final compounds 24a,b. The substitution at position 7 (rather than at position 4) for these sulfamoyl derivatives was confirmed by performing spectral analyses on intermediate 23. For this compound, the substitution pattern was established on the basis of the 1H NMR spectrum showing a pseudo triplet for H-5 at δ 7.50, as the result of the 3JH,H couplings with H-4 and H-6 protons and definitively proved on the basis of heteronuclear correlation experiments. The g-HMBC spectrum clearly showed two cross-peaks for the 3JC,H couplings of C-7a at δ 135.2 with H-4 and H-6 protons and a cross-peak for the 3JC,H coupling of C-3a at δ 124.0 with H-5. The 5-bromo derivatives 26a-h shown in the same scheme were obtained from 25a,b28 following the two procedures described for 5a-c,e and for 14c,d,g,h.

Scheme 4.

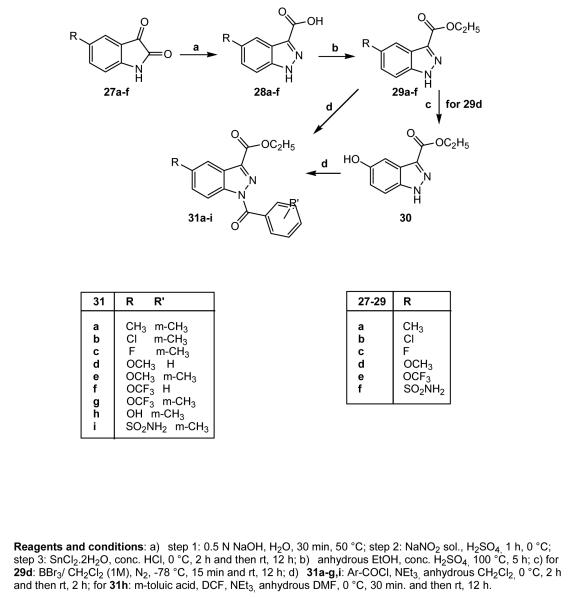

Many substituents at position 5 have been introduced following methods previously reported in the literature,35 which allowed us to obtain the indazole nucleus starting from the corresponding isatine. The synthetic route is shown in Scheme 5 using precursor isatines 27a-f (27a-e are commercially available; 27f36), which resulted in synthesis of compounds 28a-f (28a-c,37 28d,3828e39). Intermediates 28a-f were then subjected to esterification, forming 29a-f (29a-c,3729d38), which were finally converted into the desired compounds 31a-i. To obtain 31h, it was necessary to convert the OCH3 group of 29d into OH by treatment with BBr3 in CH2Cl2 under nitrogen at −78 °C, followed by treatment with m-toluic acid, Et3N, and diethylcyanophosphonate (DCF) in dimethylformamide (31h).

Scheme 5.

Lastly, the synthesis of 33 (Scheme 6) was performed, starting from precursor 3240 and using the same conditions as described for compounds 5a-c,e (see Scheme 1).

Biological Results and Discussion

Structure–Activity Relationship Analysis

All compounds were evaluated for their ability to inhibit HNE, and the results are reported in Tables 1-3, together with representative reference compounds from the previous series of N-benzoylindazole-derived HNE inhibitors (designated as compounds A through H here25. Keeping at positions 1 and 3 those substituents that produced the best results in the previous series,25 we first introduced a variety of groups at position 5 of the indazole nucleus, such as nitro, bromine, chlorine, (substituted)amino, etc. (Table 1). The introduction of substituents was generally favorable for HNE inhibitory activity and the most of the newly synthesized compounds showed 1 order of magnitude higher or a similar activity compared to the unsubstituted reference compounds A-H. In particular, introduction of a nitro group led to the most active compounds, which had IC50 values of 15-50 nM, irrespective of substituents Ar and R1 at positions 1 and 3, respectively (compounds 14a-h). Likewise, the presence of an amide (compounds 20a-c, 20f, and 20g) was beneficial for activity, and these derivatives had similar activity as the 5-nitro derivatives (IC50= 12-50 nM) (Table 1). Results for these 5-amidic derivatives (20a-g) suggested the importance of steric hindrance by the group linked to the amide CO, since the most bulky phenyl (20d) and cyclohexyl (20e) derivatives were less active by about one order of magnitude (IC50= 0.21 and 0.10 μM, respectively). Introduction of bromine resulted in increased potency for all compounds of this series (26a-h) compared to reference compounds A-H (Table 1). Compounds containing methyl (31a), chlorine (31b), fluorine (31c), methoxy (31d,e), or trifluoromethoxy (31g) at the same position increased HNE inhibitory activity by 2-3 fold compared to the reference compounds A and F, with the exception of 31f, which had an IC50= 60 nM. However, the 5-(substituted)amino derivatives 17-19 and 20h retained HNE inhibitory activity in the same activity range as reference compound A (Table 1). On the other hand, 5-OH (31h) and 5-SO2NH2 (31i) had low or no activity, respectively. Thus, the introduction of substituents at position 5 of the indazole nucleus is clearly beneficial for activity; however, there does not appear to be a generalizable correlation between activity and nature of the substituents. On the other hand, it is clear that acidic groups, such as OH and SONH2, are not tolerated at this position, since compounds 31h and 31i had low or no activity. Regarding the variety of other substituents and taking into account their different electronic and/or steric properties, we hypothesize that an electron withdrawing group within a given size is necessary to improve the potency. Aside from this characteristic, and with the exception of the limitations of an acid group mentioned above, compounds with other substituents retained similar levels of activity as their unsubstituted analogs.

Table 1.

HNE inhibitory activity of indazole derivatives 14a-h, 17-19, 20a-h, 26a-h and 31a-i

| Compd. | Ar | R1 | R2 | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14a | Ph | CH3 | NO2 | 0.03 ± 0.011 |

| 14b | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | NO2 | 0.015 ± 0.0018 |

| 14c | m-OCH3-Ph | CH3 | NO2 | 0.05 ± 0.021 |

| 14d | 3-thienyl | CH3 | NO2 | 0.05 ± 0.019 |

| 14e 22 | Ph | C2H5 | NO2 | 0.02 ± 0.018 |

| 14f | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NO2 | 0.02 ± 0.028 |

| 14g | m-OCH3-Ph | C2H5 | NO2 | 0.025 ± 0.015 |

| 14h | 3-thienyl | C2H5 | NO2 | 0.03 ± 0.031 |

| 17 | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NH2 | 0.33 ± 0.042 |

| 18 | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCH3 | 0.31 ± 0.11 |

| 19 | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | N(CH3)2 | 0.14 ± 0.23 |

| 20a | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOCH3 | 0.03 ± 0.037 |

| 20b | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOC2H5 | 0.018 ± 0.021 |

| 20c | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOnC3H7 | 0.05 ± 0.012 |

| 20d | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOPh | 0.21 ± 0.13 |

| 20e | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOcC3H5 | 0.10 ± 0.11 |

| 20f | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOcC3H5 | 0.012 ± 0.030 |

| 20g | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NHCOcC5H9 | 0.05 ± 0.029 |

| 20h | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | NH-Ph | 0.33 ± 0.052 |

| 26a | Ph | CH3 | Br | 0.08 ± 0.37 |

| 26b | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | Br | 0.08 ± 0.11 |

| 26c | m-OCH3-Ph | CH3 | Br | 0.21 ± 0.23 |

| 26d | 3-thienyl | CH3 | Br | 0.16 ± 0.21 |

| 26e 32 | Ph | C2H5 | Br | 0.05 ± 0.042 |

| 26f | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | Br | 0.08 ± 0.018 |

| 26g | m-OCH3-Ph | C2H5 | Br | 0.27 ± 0.088 |

| 26h | 3-thienyl | C2H5 | Br | 0.26 ± 0.12 |

| 31a | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | CH3 | 0.22 ± 0.052 |

| 31b | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | Cl | 0.15 ± 0.033 |

| 31c | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | F | 0.10 ± 0.019 |

| 31d | Ph | C2H5 | OCH3 | 0.08 ± 0.021 |

| 31e | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | OCH3 | 0.14 ± 0.027 |

| 31f | Ph | C2H5 | OCF3 | 0.06 ± 0.018 |

| 31g | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | OCF3 | 0.11 ± 0.028 |

| 31h | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | OH | 6.4 ± 1.1 |

| 31i | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | SO2NH2 | N.A.b |

| A 25 | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | H | 0.41 ± 0.11 |

| B 25 | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | H | 0.13 ± 0.051 |

| C 25 | m-OCH3-Ph | CH3 | H | 0.55 ± 0.21 |

| D 25 | m-OCH3-Ph | C2H5 | H | 0.8 ± 0.33 |

| E 25 | Ph | CH3 | H | 0.089 ± 0.031 |

| F 25 | Ph | C2H5 | H | 0.40 ± 0.19 |

| G 25 | 3-thienyl | CH3 | H | 0.31 ± 0.12 |

| H 25 | 3-thienyl | C2H5 | H | 0.93 ± 0.37 |

The IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

N.A., no inhibitory activity was found at the highest concentration of compound tested (50 μM).

Table 3.

HNE inhibitory activity of indazole derivatives 5a-e, 8, and 33

| Compd. | Ar | R1 | R2 | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | Ph | CN | H | 0.04 ± 0.011 |

| 5b | m-CH3-Ph | CN | H | 0.007 ± 0.0015 |

| 5c | Ph | CONH2 | H | 0.26 ± 0.042 |

| 5d | m-CH3-Ph | CONH2 | H | 12.5 ± 2.7 |

| 5e | m-CH3-Ph | CH2OCOCH3 | H | 6.4 ± 1.2 |

| 8 | m-CH3-Ph | CH2OH | H | N.A.b |

| 33 | m-CH3-Ph | CN | NO2 | 0.031 ± 0.018 |

| A 25 | m-CH3-Ph | COOC2H5 | H | 0.41 ± 0.11 |

The IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

N.A., no inhibitory activity was found at the highest concentration of compound tested (50 μM).

Evaluation of C-6 and C-7 substitutions (Table 2) showed that the 6-substituted nitroderivative 15 (IC50=20 nM) was as active as its 5-isomer 14b, while introduction of group at position 7 gave rise to inactive compounds 16, 24a, and 24b. Thus the C-6 position seems to be modifiable, while the total inactivity of 7-substituted derivatives confirms that the position neighboring the amidic nitrogen must be unsubstituted to allow free rotation of N-CO bond, which is consistent with our previous observations with other N-bezoylindazole derivatives.25

Table 2.

HNE inhibitory activity of indazole derivatives , 15, 16, and 24a,b.

| Compd. | Ar | R1 | R2 | R3 | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | NO2 | H | 0.02 ± 0.018 |

| 16 | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | H | NO2 | N.A.b |

| 24a | Ph | C2H5 | H | SO2NH2 | N.A. |

| 24b | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | H | SO2NH2 | N.A. |

| A 25 | m-CH3-Ph | C2H5 | H | H | 0.41 ± 0.11 |

| B 25 | m-CH3-Ph | CH3 | H | H | 0.13 ± 0.051 |

| F 25 | Ph | C2H5 | H | H | 0.40 ± 0.19 |

The IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

N.A., no inhibitory activity was found at the highest concentration of compound tested (50 μM).

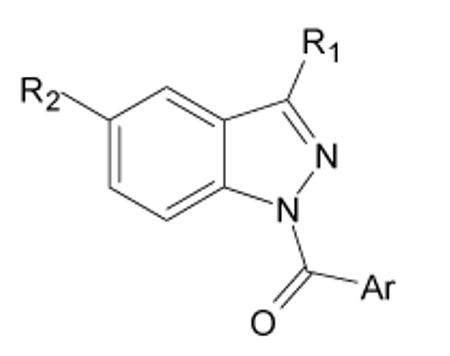

The next modifications were performed at position 3 (Table 3). The introduction of an hydroxymethyl (8) or an inverse ester (5e) was detrimental for activity, while the replacement of the ester function with a primary amide gave different results depending on the group at position 1 (5c and 5d). Conversely, a remarkable increase in potency was obtained by introducing a CN group, which resulted in the most active derivative of this series (5b) with an IC50 of 7 nM. To verify if an additive effect was possible to achieve by inserting in the same molecule both of the groups that separately led to increased activity (i.e., 5-nitro derivative 14c; 3-CN derivative 5b) we synthesized compound 33. However, no additive effects were observed, as 33 had similar inhibitory activity (IC50 = 31 nM) as the singly-substituted derivatives 14c and 5b.

Inhibitor Specificity

To evaluate inhibitor specificity, we analysed effects of the ten most potent N-benzoylindazoles on four other serine proteases, including human pancreatic chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1), human thrombin (EC 3.4.21.5), human plasma kallikrein (EC 3.4.21.34), and human urokinase (EC 3.4.21.73), and an aspartic protease, cathepsin D (EC 3.4.23.5). As shown in Table 4, none of the tested derivatives inhibited cathepsin D, and only compound 14a inhibited kallikrein. Compound 5b inhibited thrombin and urokinase at micromolar concentrations. Although all tested compounds inhibited chymotrypsin at nanomolar concentrations, compound 20f had the lowest activity for this enzyme. Moreover, only compound 20f had no inhibitory activity for urokinase (Table 4). Thus, compounds 5b and 20f appear to be the most specific HNE inhibitors.

Table 4.

Analysis of inhibitory specificity for selected indazole derivatives

| Compd. | Thrombin | Chymotrypsin | Kallikrein | Urokinase | Cathepsin D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM)a | |||||

| 5b | 1.9 ± 0.62 | 0.066 ± 0.019 | N.A.b | 6.6 ± 2.7 | N.A. |

| 14f | 0.48 ± 0.12 | 0.040 ± 0.012 | N.A. | 1.5 ± 0.65 | N.A. |

| 14g | 0.082 ± 0.033 | 0.021 ± 0.057 | N.A. | 0.48 ± 0.11 | N.A. |

| 20a | 0.31 ± 0.059 | 0.17 ± 0.049 | N.A. | 13.7 ± 3.6 | N.A. |

| 14h | 0.37 ± 0.12 | 0.046 ± 0.003 | N.A. | 25.3 ± 6.2 | N.A. |

| 14a | 0.83 ± 0.14 | 0.031 ± 0.008 | 11.2 ± 2.6 | 0.62 ± 0.17 | N.A. |

| 14b | 1.1 ± 0.35 | 0.015 ± 0.004 | N.A. | 0.44 ± 0.13 | N.A. |

| 15 | 0.64 ± 0.19 | 0.038 ± 0.012 | N.A. | 0.31 ± 0.018 | N.A. |

| 20b | 0.039 ± 0.011 | 0.14 ± 0.026 | N.A. | 14.8 ± 4.6 | N.A. |

| 20f | 0.16 ± 0.035 | 0.37 ± 0.045 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

The IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

N.A., no inhibition activity was found at the highest concentration of compound tested (50 μM).

Stability and Kinetic Features

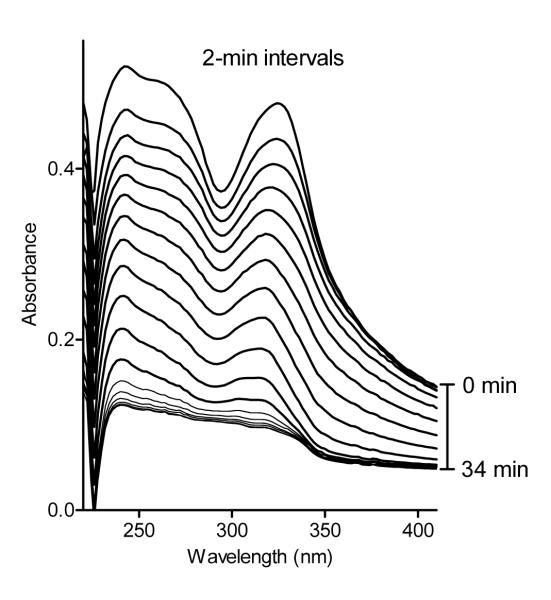

The most potent and specific N-benzoylindazoles were further evaluated for chemical stability in aqueous buffer using spectrophotometry to detect compound hydrolysis. As shown in Figure 1, the absorbance maxima at 242 and 322 nm for compound 5b decreased over time, indicating that this compound was hydrolyzed almost completely after 35 min in aqueous buffer with a t½ of 21.7 min. The other nine compounds had t½ values from 27.2 to 117.5 min (Table 5), indicating that the tested N-benzoylindazoles were more stable than our previously described HNE inhibitors with the N-benzoylpyrazole scaffold.25

Figure 1.

Analysis of changes in compound absorbance resulting from spontaneous hydrolysis. The changes in absorbance spectra of compound 5b (20 μM) were monitored over time with 2-min intervals in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5, 25 °C). Representative scans are from three independent experiments.

Table 5.

Half-life (t1/2) for the spontaneous hydrolysis of selected indazole derivatives

| Compd. | Max (nm)a | t½ (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 5b | 242 | 21.7 |

| 14f | 274 | 117.5 |

| 14g | 272 | 27.2 |

| 20a | 262 | 78.8 |

| 14h | 272 | 32.8 |

| 14a | 268 | 37.9 |

| 14b | 270 | 47.8 |

| 15 | 268 | 41.5 |

| 20b | 266 | 51.0 |

| 20f | 266 | 51.7 |

Absorption maximum used for monitoring spontaneous hydrolysis.

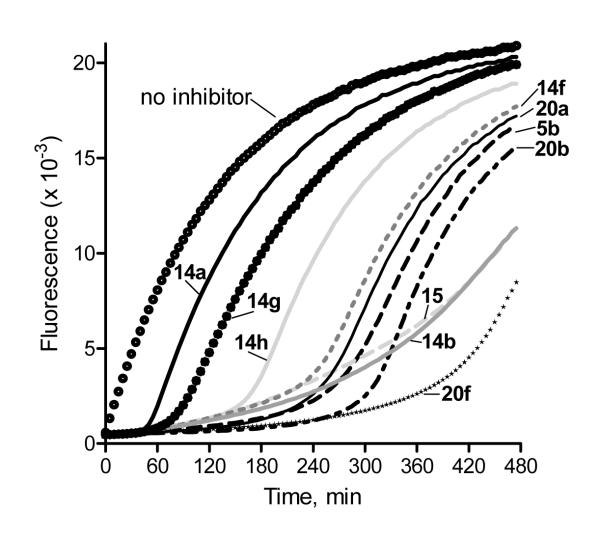

The relatively rapid rate of spontaneous hydrolysis allowed us to evaluate inhibitor reversibility over time. As shown in Figure 2, inhibition was maximal during the first 5 h for compounds 20b and 20f and during the first 4 h for compounds 5b, 14b, 14f, 15, and 20a at 5 μM concentrations. However, inhibition by compounds 14a, 14g, and 14h was soon reversed, and recovery of HNE activity was observed by ~1-2 h after treatment with up to 5 μM of these compounds (Figure 2). Although the rate of reversibility for the last three compounds (14a, 14g, and 14h) correlated with the rate of spontaneous hydrolysis, this was not the case for the other N-benzoylindazole derivatives tested. For example, hydrolysis of the acyl-enzyme complex for compound 5b was much slower than spontaneous hydrolysis of this nitrile derivative, and HNE was still inhibited to 80% of control level at 7 h after treatment (compare Figures 1 and 2). Thus, these results suggest that the active N-benzoylindazoles may be pseudoirreversible HNE inhibitors, which covalently attack the enzyme active site but can be reversed by hydrolysis of the acyl-enzyme complex, which is similar to the structurally-related N-benzoylpyrazole-derived HNE inhibitors.25

Figure 2.

Evaluation of HNE inhibition by selected indazole derivatives over time. HNE was incubated with the indicated compounds at 5 μM concentrations, and kinetic curves monitoring substrate cleavage catalyzed by HNE from 0 to 7 h are shown. Representative curves are from three independent experiments.

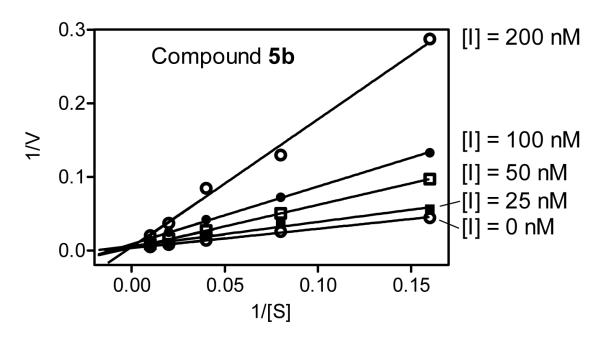

To better understand the mechanism of action of these N-benzoylindazole HNE inhibitors, we performed kinetic experiments with two of the most active compounds that had favorable specificity profiles (5b and 20f). As shown in Figure 3, the representative double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plot of fluorogenic substrate hydrolysis by HNE in the absence and presence of compound 5b indicates that this compound is a competitive HNE inhibitor. Similar results were observed for the kinetic analysis of compound 20f (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of HNE inhibition by compound 5b. Representative double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plot from three independent experiments.

Molecular Modeling

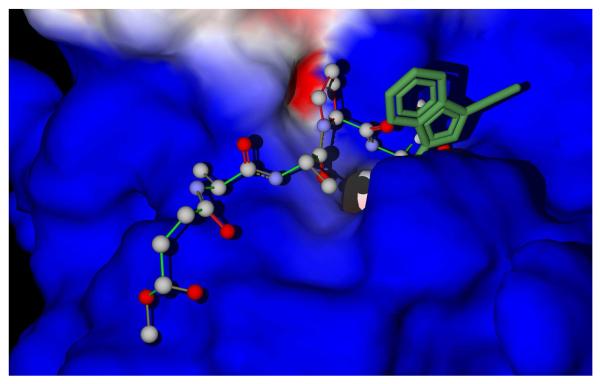

To evaluate complementarity of the inhibitors to the HNE binding site, we performed molecular docking studies of selected compounds (5b, 5d, 8, 14f, 26b, and 31h) into the HNE binding site using the HNE structure from the Protein Data Bank (1HNE entry) where the enzyme is complexed with a peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor.41 Previously, we used an approach where the HNE conformation was adopted to be rigid, and a limited refinement of docking poses was undertaken with flexibility of only three residues (His57, Asp102, and Ser195) representing the catalytic triad of serine proteases.25,27 In the present study, we applied a more sophisticated methodology and performed docking with 42 flexible residues in the vicinity of the HNE binding site (see Experimental) using Molegro software.

The search area for docking was defined as a sphere 10 Å in radius centered at the nitrogen atom of the 5-membered ring of the complexed inhibitor from the PDB file. This sphere embraced almost the entire peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor molecule and the nearest HNE residues, including the catalytic triad of His57, Asp102, and Ser195. The best docking poses obtained are located near the tail of the co-crystallized peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor (see in Figure 4 where the peptide and the pose of compound 5b are shown superimposed).

Figure 4.

Superimposed docking poses of compound 5b (dark-green) and peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor. The peptide inhibitor is shown with a ball-stick rendering. The surface corresponds to the initial enzyme structure from the PDB file.

Analysis of the docking poses was performed to determine the distances d1-d3 and angle O(Ser195)…C=O (α, Supplemental Figure 1S) important for the consideration of Michaelis complex formation and for easy proton transfer within the oxyanione hole.42-44 The geometric parameters of the lowest-energy enzyme-inhibitor complexes obtained by docking are presented in Table 6. Although the docking poses are not Michaelis complexes themselves, it is reasonable to regard their structures as approximations to the geometries of these complexes, keeping in mind that many residues were treated as flexible in the docking procedure. According to previous reports,42,43 it is optimal when the Michaelis complex formed with participation of an inhibitor’s amido moiety has the ligand carbonyl carbon atom located 1.8-2.6 Å from the Ser195 hydroxyl oxygen (distance d1), while the angle α is within 80-120°. As shown in Table 6, the highly active compounds 5b, 14f, and 26b in their best docking poses had shorter d1 values than the less active inhibitors 5d and 31h or inactive compound 8. Hence, the distance optimal for Michaelis complex is more attainable from these poses. Moreover, all active inhibitors were characterized by angle α in the optimal range (5b, 5d, and 31h) or close to this range (14f and 26b). On the other hand, angle α was too obtuse in the docking pose of inactive compound 8 (Table 6). A visual inspection of this pose (Supplemental Figure S2) indicated that an optimal value of α is hardly reachable from the calculated binding mode of 8 because the molecule is anchored by strong H-bonds formed between the oxymethyl group and backbone heteroatoms in Cys191 and Ser195. Thus, such an anchoring causes a very high energy barrier for reorienting 8 to form the Michaelis complex within the binding site.

Table 6.

Biological activities of HNE inhibitors and geometric parameters of the enzyme-inhibitor complexes predicted by docking

| Compd. | IC50 (μM)a | α | d1 | d2 | d3 | Lb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5b | 0.007 | 119.3 | 3.448 | 2.181; 3.755 | 3.142 | 5.323 |

| 5d | 12.5 | 105.5 | 4.348 | 5.702; 5.844 | 2.449 | 8.151 |

| 8 | N.A. | 169.4 | 4.590 | 1.796; 3.357 | 3.272 | 5.068 |

| 14f | 0.02 | 129.8 | 4.079 | 2.158; 3.749 | 3.119 | 5.277 |

| 26b | 0.08 | 75.5 | 3.874 | 1.730; 3.312 | 2.753 | 4.483 |

| 31h | 6.4 | 96.4 | 4.222 | 2.362; 3.959 | 3.303 | 5.665 |

HNE inhibitory activity.

Length of the channel for proton transfer calculated as d3+min(d2).

The three residues His57, Asp102, and Ser195 form a catalytic triad, which acts as general base and enhances nucleophilicity of Ser195 by the synchronous proton transfer from the OH group of Ser195 to Asp102 through the His57 imidazole moiety.41,45,46 Conformational changes of the enzyme in the process of Michaelis complex formation can destroy the channel of proton transfer because of possible unfavorable orientation of the residues in the catalytic triad. To evaluate conditions for synchronous proton transfer, we have calculated an effective length (L) of the channel as a sum of distances d2 and d3 (Supplemental Figure S1). The most active compounds (5b, 14f, and 26b) had shorter L values than the moderately active inhibitors 5d and 31h (Table 6). Although a relatively low L was obtained for inactive compound 8, the main reason of its inactivity is the unfavorable positioning of the ligand due to H-bond formation, as described above.

The results of this investigation, as well as those of our previous studies25,27, show that HNE inhibitory activity strongly depends on the geometric characteristics of ligand-enzyme complexes. The ability of a ligand to form a Michaelis complex and favorable conditions for proton transfer within the binding site affected inhibitor activity. Hence, both an inhibitor orientation with respect to Ser195 and the relative positioning of residues in the catalytic triad are important.

Conclusions

These results confirm that the N-benzoylindazole scaffold is an appropriate structure for development of potent HNE inhibitors and that, by maintaining a benzoyl substituent at N-1, which is essential for activity, it is possible to increase the potency by inserting substituents at the phenyl ring of the indazole. In particular, the best results were obtained introducing nitro, bromine, or acylamino groups at position 5, which resulted in corresponding HNE inhibitors with IC50 values of 12-50 nM. Furthermore, modifications at position 3 led to the most potent HNE inhibitor, 5b, with IC50=7 nM. Analysis of specificity showed that compounds 5b and 20f were relatively selective for HNE versus other proteases evaluated. Finally, molecular docking studies strongly suggested that the geometry of ligand-enzyme complexes was the main factor influencing interaction of inhibitors with the HNE binding site. Besides the ability of a compound to form a Michaelis complex, a suitable orientation of His57, Asp102, and Ser195 was also important for effective proton transfer from the oxyanione hole. Thus, the novel HNE inhibitors reported here represent potential leads for future optimization and in vivo studies.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

All melting points were determined on a Büchi apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded with an Avance 400 instrument (Bruker Biospin Version 002 with SGU). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, using the solvent as internal standard. Extracts were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure. Merck F-254 commercial plates were used for analytical TLC to follow the course of reaction. Silica gel 60 (Merck 70-230 mesh) was used for column chromatography. Microanalyses were performed with a Perkin-Elmer 260 elemental analyzer for C, H, and N, and the results were within ± 0.4 % of the theoretical values, unless otherwise stated. Reagents and starting materials were commercially available.

Acetic Acid 1H-indazol-3-yl Methyl Ester (2)

A mixture of 130 (0.2 mmol), 1 mL of acetic acid, and 0.12 mL of conc. H2SO4 was heated at 100 °C for 2 h. After cooling, cold water was added, and the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in compound 2. Yield = 98%; oil; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.17 (s, 3H, CH3), 5.60 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.30 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.54 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.64 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.88 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz).

General Procedure for 5a-c, and 5e

To a cooled (0 °C) suspension of the appropriate substrate 2, 328, or 429 (0.42 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (1-2 mL), a catalytic amount of Et3N (0.05 mL) and the (substituted)-benzoyl chloride (1.26 mmol) were added. The solution was stirred at 0 °C for 1-2 h and then for 1-3 h at room temperature. The precipitate was removed by suction, and the organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The residue mixed in with ice-cold water (20 mL), neutralized with 0.5 N NaOH, and the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds 5a-c and 5d, which were purified by crystallization from ethanol (compounds 5a, b) or by column chromatography using cycloexane/ethyl acetate 2:1 (for 5c) or toluene/ethyl acetate 9.5:0.5 (for 5e) as eluent.

1-Benzoyl-1H-indazole-3-carbonitrile (5a)

Yield = 35%; mp = 156-157 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.63-7.74 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.88 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.00-8.03 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.10 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.52 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carbonitrile (5b)

Yield = 22%; mp = 135-136 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.43 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.48-7.57 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.68 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.81 (s, 2H, Ar), 7.87 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.09 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.51 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz). 1-Benzoyl-1-H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Amide (5c): Yield = 10%; mp = 204-206 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) 7.53-7.62 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.69-7.76 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.84 (exch br s, 1H, NH2), 7.94 (exch br s, 1H, NH2), 8.14 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.29 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.47 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz).

Acetic acid 1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazol-3-yl-Methyl Ester (5e)

Yield = 22%; mp = 135-136 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.16 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 2.48 (s, 3H, COCH3), 5.50 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.42-7.47 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.66 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.85 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.89 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.58 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Amide (5d)

To a cooled (−5 to −7 °C) suspension of m-toluic acid (0.62 mmol) in anhydrous THF (5 mL), 2.17 mmol of Et3N was added. The suspension was stirred for 30 min, and after warming up to 0 °C, ethyl chloroformate was added (0.68 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 1 h, and then 1.24 mmol of 328 was added. The reaction was carried out at room temperature for 12 h, and evaporation of the solvent resulted in the desired final compound, which was purified by column chromatography (cycloexane/ethyl acetate gradient 4:1 to 3:1). Yield = 10%; mp = 220 °C dec. (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.33 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.98 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.22 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.60 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.73 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.83 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.93 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.55 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 10.81 (exch br s, 2H, NH2).

3-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxymethyl)-1H-indazole (6)

To a mixture of a catalytic amount of ammonium cerium (IV) nitrate (CAN) in anhydrous CH3CN (2.5 mL), 0.53 mmol of 130 and 0.53 mmol of 3,4 dihydro-2H-pyran (commercially available) were added, and the suspension was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After evaporation of the solvent, water was added (20 mL), the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic layer was evaporated in vacuo, resulting in crude 6, which was purified by column chromatography using CH2Cl2/CH3OH 9.5:0.5 as eluent. Yield = 33%; oil; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.59-1.86 (m, 6H, cC5H9O), 3.60-3.78 (m, 1H, cC5H9O), 3.90-4.05 (m, 1H, cC5H9O), 4.83 (s, 1H, O-CH-O), 4.90-5.00 (m, 1H, C-CH2-O), 5.15-5.22 (m, 1H, C-CH2-O) 7.15-7.22 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.37-7.51 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.87-7.93 (m, 1H, Ar), 10.62 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

3-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxymethyl)-indazol-1-yl]-m-tolyl-methanone (7)

Compound 7 was obtained starting from intermediate 6 by reaction with m-toluoyl chloride, following the general procedure described for 5a-c and 5e. After evaporation of the solvent, the final compound was purified by column chromatography using toluene/ethyl acetate 9.5:0.5 as eluent. Yield = 50%; oil; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.60-1.88 (m, 6H, cC5H9O), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.55-3.65 (m, 1H, cC5H9O), 3.90-4.06 (m, 1H, cC5H9O), 4.84 (s, 1H, O-CH-O), 4.90-4.98 (m, 1H, C-CH2-O), 5.10-5.20 (m, 1H, C-CH2-O), 7.42 (s, 3H, Ar), 7.57-7.68 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.89 (s, 2H, Ar), 7.90-8.00 (m, 1H, Ar), 8.52-8.61 (m, 1H, Ar).

(3-Hydroxymethyl-indazol-1-yl)-m-tolylmethanone (8)

A mixture of 7 (0.09 mmol), trifluoroacetic acid (0.28 mL), and CH2Cl2 (1.72 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. Evaporation of the solvent resulted in compound 8, which was purified by column chromatography using CH2Cl2/CH3OH 9.9:0.1 as eluent. Yield = 87%; oil; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.20 (exch br s, 1H, OH), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 5.08 (s, 2H, CH2OH) 7.44 (s, 3H, Ar), 7.62 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.80-7.91 (m, 3H, Ar), 8.50-8.56 (m, 1H, Ar).

6-Nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (12b)

To a cooled and stirred solution of conc. H2SO4 and conc. HNO3 (1.5 mL, 1:1, v/v), 0.45 mmol of 10 was slowly added, and the mixture was kept under stirring at 0 °C for 10 min. After dilution with ice-cold water, the precipitate was filtered and washed with water (10-20 mL). Finally, compound 12b was purified by column chromatography using cycloexane/ethyl acetate 4:1 as eluent. Yield = 10%; mp = 120-121 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.54 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.64 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.46 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.6 Hz), 8.73 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.27 (s, 1H, Ar), 11,67 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

General Procedures for 14a,b, and 14f

Compounds 14a,b and 14f were obtained starting from 11a and 11b, respectively, following the general procedure described for 5a-c and 5e. For compound 14a, after dilution with cold water and neutralization with 0.5 N NaOH, the precipitate was filtered off and purified by crystallization from ethanol. For compound 14b and 14e, after dilution and neutralization with NaOH, the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL), and evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds, which were recrystallized from ethanol.

1-Benzoyl-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (14a)

Yield = 62%; mp = 156-157 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.13 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.60 (t, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.72 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.19 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.56 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.73 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.23 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz). 1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (14b): Yield = 52%; mp = 180-181 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph ), 4.13 (s, 3H, OCH3), 7.47-7.53 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.90 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.55 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.71 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.22 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz). 1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (14f): Yield = 76%; mp = 150-153 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.54 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.50 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.62 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.47-7.54 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.98 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.54 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.71 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.22 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz).

General Procedures for 14c,d, and 14g,h

The appropriate (hetero)arylcarboxylic acids (0.90 mmol) were dissolved in 2 mL of SOCl2 and heated at 80-90 °C for 1 h. After cooling, excess SOCl2 was removed under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in 3.5 mL of anhydrous toluene. A solution of 11a32 or 11b32 (0.45 mmol) and Et3N (0.50 mmol) in anhydrous toluene (3.5 mL) was added to this mixture, and it was stirred at 110 °C for 3-6 h. After cooling, the precipitate was removed by filtration, and the organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum. Addition of cold water to the residue and neutralization with 0.5 N NaOH resulted in the final compounds. Compounds 14c, 14g, and 14h were recovered by suction and recrystallized from ethanol, while the crude 14d was recovered by extraction with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL) and evaporation of the solvent. Compound 14d was finally crystallized from ethanol.

1-(3-Methoxybenzoyl)-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (14c)

Yield = 56%; mp = 151-152 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 3.93 (s, 3H, Ph-OCH3), 4.13 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 7.25 (dd, 1H, Ar, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 5.6 Hz), 7.50 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.71 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.78 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7,6 Hz), 8.56 (dd, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.72 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.22 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz).

5-Nitro-1-(thiophene-3-carbonyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (14d)

Yield = 54%; mp = 193-194 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.17 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.47 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.02 (m, 1H, Ar), 8.54 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.77 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.00 (s, 1H, Ar), 9,21 (s, 1H, Ar).

1-(3-Methoxybenzoyl)-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (14g)

Yield = 54%; mp = 193-194 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.53 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.93 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.61 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.25 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.6 Hz), 7.50 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.74 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.80 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.55 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.72 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9,22 (s, 1H, Ar).

5-Nitro-1-(thiophene-3-carbonyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (14h)

Yield = 48%; mp = 156-159 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.53 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.65 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.43-7.49 (m, 1H, Ar), 8.02 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.53 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.76 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 9.01 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 1.6 Hz), 9.2 (m, 1H, Ar).

General Procedures for 15 and 16

Compounds 15 and 16 were obtained starting from compounds 12a33 and 1334 following the same procedure described for 5a-c and 5e. After dilution with cold water and neutralization with 0.5 N NaOH, the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds, which were purified by column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 4:1 as eluent.

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-6-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (15)

Yield = 5%; mp = 180-181 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph ), 4.13 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.47-7.54 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.94-7.99 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.55 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.71 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 9.22 (m, 1H, Ar).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-7-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (16)

Yield = 17%; mp = 118-119 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.56 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.49-7.56 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.65 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.99 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.23 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.66 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz).

5-Amino-1-(3 methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (17)

Compound 14f (0.31 mmol) was subjected to catalytic reduction in EtOH (6 mL) for 2 h with a Parr instrument using 70 mg of 10% Pd/C as catalyst and the pressure kept constant at 30 psig. The catalyst was filtered off, and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum, resulting in the final compound, which was purified by crystallization from ethanol. Yield = 30%; mp = 131-133 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.48 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 3.94 (exch br s, 2H, NH2), 4.52 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.05 (dd, 1H, Ar, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.40-7.46 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.47 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.94 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.36 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz).

General Procedures for 18 and 19

A mixture of 0.31 mmol of 17, 0.68 mmol of K2CO3, and 0.54 mmol of CH3I in 1 mL of anhydrous DMF was stirred at 50 °C for 3 h. After cooling, ice-cold water was added (10-15 mL), and the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The organic layer was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 3:1 as eluent.

5-Methylamino-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (18)

Yield = 34%; mp = 152-154 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.49 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 2.98 (s, 3H, NCH3), 4.02 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 4.53 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.99 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.30 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.40-7.47 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.96 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.35 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

5-Dimethylamino-1-(3 methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (19)

Yield = 28%; mp = 114-116 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.49 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 3.09 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 4.53 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.21 (d, 1H, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.40-7.48 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.97 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.41 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

General Procedures for 20a-f

To a cooled (0 °C) suspension of 17 (0.31 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (2 mL), a catalytic amount of Et3N and 0.93 mmol of the appropriate (cyclo)alkylcarbonyl or benzoylchloride were added. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h and then at room temperature for 2 h. Finally, the precipitates were recovered by vacuum filtration and recrystallized with ethanol.

5-Acetylamino-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20a)

Yield = 27%; mp = 155-158 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.39 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.12 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.43 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.44 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.49-7.57 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.80-7.86 (m, 3H, Ar), 8.38 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.65 (s, 1H, Ar), 10.32 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-propionylamino-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20b)

Yield = 95%; mp = 116-119 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.32 (t, 3H, COCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.51 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 2.51 (q, 2H, COCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.55 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.42-7.48 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.83 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.95 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.46 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 8.51 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

5-Butyrylamino-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20c)

Yield = 72%; mp = 122-125 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.07 (t, 3H, CH2CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.51 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.84 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.43 (t, 2H, COCH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.54 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.37 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.42-7.48 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.82 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.96 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.46 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 8.51 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz).

5-Benzoylamino-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20d)

Yield = 78%; mp = 196-198 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.52 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.42-7.47 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.55-7.60 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.94-8.00 (m, 5H, Ar), 8.04 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 8.58 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 9.2).

5-(Cyclohexanecarbonylamino)-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20e)

Yield = 64%; mp = 189-191 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.29-1.39 (m, 3H, cC6H11), 1.51 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.63 (t, 2H, cC6H11, J = 5.6 Hz), 1.70-1.80 (m, 1H, cC6H11), 1.85-1.95 (m, 2H, cC6H11), 2.00-2.2.05 (m, 2H, cC6H11), 2.28-2.38 (m, 1H, cC6H11), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J= 7.2 Hz), 7.3287.40 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.40-7.46 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.84 (d, 1H, Ar, J= 9.6 Hz), 7.96 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.45 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 8.51 (d, 1H, Ar, J= 8.4 Hz).

5-(Cyclopropanecarbonylamino)-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20f)

Yield = 82%; mp = 204-205 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 0.92 (m, 2H, cC3H11), 1.17 (m, 2H, cC3H11), 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.58 (m, 1H, cC3H11), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.53 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J= 7.2 Hz), 7.42-7.47 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.60 (exch br s, 1H, NH), 7.,85 (d, 1H, Ar), 7.95 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.44 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.50 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

5-(Cyclopentanecarbonylamino)-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20g)

Compound 20g was obtained starting from 17 following the same procedure described for 14c,d,g,h. After dilution with cold water, the mixture was neutralized with 0.5 N NaOH and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in a residue, which was purified by crystallization from ethanol. Yield = 20%; mp = 157-160 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.65-1.70 (m, 2H, cC5H9), 1.85-1.88 (m, 2H, cC5H9), 1.95-2.01 (m, 4H, cC5H9), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 2.73-2.80 (m, 1H, cC5H9), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.38-7.47 (m, 3H, 1H NH e 2H Ar), 7.85 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.95 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.46 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.50 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-phenylamino-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (20h)

A mixture of activated powdered 4A molecular sieves (500 mg), 0.30 mmol of 17, 5 mL of anhydrous CH2Cl2, 0.60 mmol of phenylboronic acid, 0.45 mol of Cu(Ac)2, and 0.60 mol of Et3N was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. Molecular sieves were removed by suction filtration, and the organic layer was washed with 33% aqueous ammonia (3 × 5 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compound, which was purified by flash chromatography using toluene/ethyl acetate 7:3 as eluent. Yield = 71%; mp = 123-125 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.45 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.46 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.50 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.03 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.34 (t, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.39-7.44 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.94 (s, 3H, Ar), 8.44 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.95 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

7-Sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid (22)

To 0.43 mmol of 21 (commercially available) cooled at 0 °C, 1 mL of chlorosulfonic acid was slowly added. The mixture was stirred at 80-90 °C for 4-5 h. After cooling, ice-cold water (15 mL) and 33% aqueous ammonia (5 mL) were added, resulting in a precipitate, which was recovered by suction. Yield = 10%; mp = 257 °C dec. (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 6.50 (exch br s, 1H, OH), 7.24 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.73 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 6.8 Hz), 8.10 (exch br s, 2h, NH2), 8.45 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz).

7-Sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (23)

A mixture of 22 (0.62 mmol) and a catalytic amount of conc. H2SO4 in anhydrous ethanol (7.5 mL) was heated at 100 °C for 5 h. After cooling, ice-cold water was added, and the precipitate was recovered by suction and recrystallized from ethanol. Yield = 48%; mp = 244 °C dec. (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.40 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.43 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2Hz), 7.50 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.71 (exch br s, 2H, SO2NH2), 7.90 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.34 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0Hz), 13.91 (exch br s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 14.4 (q), 60.9 (t), 122.7 (d), 124.0 (s), 125.7 (2 × d), 127.5 (s), 135.2 (s), 136.0 (s), 162.0 (s).

General Procedures for 24a,b

Compounds 24a,b were obtained starting from 23 following the general procedure described for 5a-c,e. After dilution with water and neutralization with 0.5 NaOH, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). Evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds, which were purified by flash chromatography using as eluents cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 2:1 for 24a and 1:2 for 24b.

1-Benzoyl-7-sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (24a)

Yield = 29%; mp = 139-140 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.38-1.42 (m, 3H, CH3), 4.45-4.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.61-7.70 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.72-7.80 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.90-8.05 (m, 1H, Ar), 8.15 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 6.8 Hz), 8.45 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.52 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-7-sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (24b)

Yield = 17%; mp = 176-178 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50-1.60 (m, 3H, CH3), 2.51 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.58-4.65 (m, 2H, CH2), 7.52 (s, 2H, Ar), 7.80-7.90 (m, 1H, Ar), 8.17 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.22-8.27 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.51 (d, 1H, Ar).

General Procedures for 26a,b and 26f

Compounds 26a,b and 26f were obtained starting from 25a,b32 following the same general procedure described for 5a-c,e. For compound 26a, after dilution with water and neutralization with NaOH, the crude precipitate was recovered by suction and crystallized by ethanol. The suspension of 26b and 26f was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL), and evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds, which were recrystallized from ethanol.

1-Benzoyl-5-bromo-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (26a)

Yield = 82%; mp = 143-146 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.08 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.55-7.60 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.65-7.71 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.77 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.12-8.17 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.47 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 6.4 Hz), 8.49 (s, 1H, Ar).

5-Bromo-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (26b)

Yield = 58%; mp = 121-123 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.07 (s, 3H, OCH3), 7.43-7.49 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.77 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.93 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.46 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.48 (s, 1H, Ar).

5-Bromo-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (26f)

Yield = 50%; mp = 116-117 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.43-7.49 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.76 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.95 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.45 (s, 2H, Ar).

General Procedures for 26c,d, and 26g,h

These compounds were obtained starting from compounds 25a32 or 25b32 following the general procedure described for 14c,d,g,h. For 26d and 26h, the precipitate was recovered by suction and recrystallized from ethanol; for compounds 26c and 26g, after dilution and neutralization with 0.5 N NaOH, the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL), and evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compounds, which were purified by crystallization from ethanol.

5-Bromo-1-(3-methoxybenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (26c)

Yield = 26%; mp = 105-108 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.07 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 7.21 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.47 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.68 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.76 (t, 2H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.45-8.53 (m, 2H, Ar).

5-Bromo-1-(thiophene-3-carbonyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Methyl Ester (26d)

Yield = 36%; mp = 136-138 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.12 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.43 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.75 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.99 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.46 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.50 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.94 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 3.2 Hz).

5-Bromo-1-(3-methoxybenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (26g)

Yield = 54%; mp = 115-117 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.21 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.47 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.72 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.77 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.46 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz).

5-Bromo-1-(thiophene-3-carbonyl)-1H-indazole 3 carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (26h)

Yield = 35%; mp = 106-108 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.53 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.60 (q, 2H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.40-7.7.45 (m, 1H, Ar), 7.75 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.00 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.45 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.50 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.96 (s, 1H, Ar).

5-Sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid (28f)

A mixture of 27f36 (0.31mmol) and 0.32 mmol of 0.5 N NaOH in 1 mL of water was stirred at 50 °C for 30 min. After cooling, a solution of NaNO2 (0.31 mol) in water (0.1 mL) followed by a solution of conc. H2SO4 (0.60 mmol) in 0.8 mL of cold water were added, maintaining the mixture reaction under stirring at 0 °C for 1 h. Finally, a cold solution of SnCl2 (0.74 mmol) in 0.5 mL of conc. HCl was added, and the mixture was stirred for further 2 h at 0 °C and 16 h at room temperature. The precipitate was recovered by suction. Yield = 38%; mp > 300 °C dec. (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 6.10 (exch br s, 1H, OH), 7.57 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.68 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.18 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.40 (exch br s, 2H, NH2), 13.95 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

General Procedures for 29e,f

Compounds 29e and 29f were obtained starting from 28e39 and 28f and following the same procedure described for compound 23.

5-Trifluoromethoxy-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (29e)

Yield = 45%; mp = 179-181 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.53 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.57 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.70 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.11 (s, 1H, Ar), 12.87 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

5-Sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (29f)

Yield = 95%; mp = 290 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.15-1.25 (m, 3H, CH3), 4.24 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz) 7.62 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.72 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.08 (s, 1H, Ar), 9.05 (exch br s, 2H, NH2), 14.10 (exch br s, 1H, NH).

5-Hydroxy-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (30)

To a cooled (−78 °C) solution of 29d38 (1.08 mmol) in 1 mL of anhydrous CH2Cl2, 4.15 mL of BBr3 (1M in CH2Cl2) were added. The reaction was carried out under nitrogen, and after 10 min the mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 3 h. After dilution with water, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL), and the organic layers were evaporated to obtain compound 30, which was purified by flash column chromatography using cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1 as eluent. Yield = 14%; oil; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.51 (t, 3H, CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.53 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.11 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.47 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.61 (s, 1H, Ar).

General Procedures for 31a-g and 31i

Compounds 31a-g and 31i were obtained following the general procedure described for 5a-c and 5e starting from compounds 29a-f (29a-c37 and 29d38). Compounds 31a-g were recrystallized from ethanol, while compound 31i was purified by flash chromatography using toluene/ethyl acetate 99:1 as eluent.

5-Methyl-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31a)

Yield = 13%; mp = 88 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 2.57 (s, 3H, 5-CH3.), 4.54 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.43-7.45 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.50 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.93-7.97 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.07 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.45 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.4 Hz).

5-Chloro-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31b)

Yield = 27%; mp = 108 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.4387.49 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.63 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.95 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.28 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.52 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

5-Fluoro-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31c)

Yield = 23%; mp = 105 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.50 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.55 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.40-7.49 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.92-7.96 (m, 3H, Ar), 8.56 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 5.2 Hz).

1-Benzoyl-5-methoxy-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31d)

Yield = 21%; mp = 111-112 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.38 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.90 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.45 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.58-7.72 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.78-7.82 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.37 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz).

5-Methoxy-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31e)

Yield = 20%; mp = 89-90 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.37 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.42 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 3.90 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.44 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.48-7.53 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.58 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.78-7.82 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.35 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz).

1-Benzoyl-5-trifluoromethoxy-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31f)

Yield = 22%; mp = 91-92 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.51 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.56 (q, 2H, CH3CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.54-7.60 (m, 3H, Ar), 7.68 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 8.16-8.19 (m, 3H, Ar), 8.62 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-trifluoromethoxy-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31g)

Yield = 28%; mp = 112-113 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.51 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.48 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.56 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.43-7.50 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.54 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.96 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.16 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.61 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-sulfamoyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31i)

Yield = 28%; mp = 52-54 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.43 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.46 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.49 (q, 2H, CH2, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.41-7.47 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.83 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.91 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.46 (s, 1H, Ar), 8.53 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz).

5-Hydroxy-1-(3-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (31h)

To a cooled and stirred solution of m-toluic acid (0.52 mmol) and Et3N (0.05 mL) in anhydrous DMF (1-2 mL), diethylcyanophosphonate (DCF) (2.08 mmol) and 0.52 mmol of 30 were added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. After dilution with ice-cold water (10 mL), the suspension was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL), and evaporation of the solvent resulted in the final compound, which was purified by column chromatography using toluene/ethyl acetate 8:2 as eluent. Yield = 51%; mp = 145-146 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.49 (t, 3H, CH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.47 (s, 3H, Ph-CH3), 4.53 (q, 2H, CH3CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.23 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.42-7.45 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.65 (s, 1H, Ar), 7.96 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.46 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.2 Hz).

1-(3-Methylbenzoyl)-5-nitro-1H-indazole-3-carbonitrile (33)

Compound 33 was obtained starting from compound 3240 and following the general procedure described for 5a-c and 5e. The final compound was purified by flash chromatography using toluene/ethyl acetate 8:2 as eluent. Yield = 32%; mp = 140-143 °C (EtOH); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.50 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.55 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.90 (s, 2H, Ar), 8.62 (dd, 1H, Ar, J = 2.0 Hz, J = 9.6 Hz), 8.77 (d, 1H, Ar, J = 9.6 Hz), 8.89 (s, 1H, Ar).

HNE Inhibition Assay

Compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO at 5 mM stock concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO in the reactions was 1%, and this level of DMSO had no effect on enzyme activity. The HNE inhibition assay was performed in black, flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates. Briefly, a buffer solution containing 200 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.01% bovine serum albumin, and 0.05% Tween-20 and 20 mU/mL of HNE (Calbiochem) was added to wells containing different concentrations of each compound. Reactions were initiated by addition of 25 μM elastase substrate (N-methylsuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin, Calbiochem) in a final reaction volume of 100 μL/well. Kinetic measurements were obtained every 30 s for 10 min at 25 °C using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence microplate reader (Thermo Electron, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 355 and 460 nm, respectively. For all compounds tested, the concentration of inhibitor that caused 50% inhibition of the enzymatic reaction (IC50) was calculated by plotting % inhibition versus logarithm of inhibitor concentration (at least six points). The data are presented as the mean values of at least three independent experiments with relative standard deviations of <15%.

Analysis of Inhibitor Specificity

Selected compounds were evaluated for their ability to inhibit a range of proteases in 100 μL reaction volumes at 25 °C, as described previously.25 Briefly, analysis of chymotrypsin inhibition was performed in reaction mixtures containing 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 30 nM human pancreas chymotrypsin, test compounds, and 100 μM substrate (Suc-Ala–Ala-Pro-Phe-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin). Thrombin inhibition was evaluated in reaction mixtures containing 0.25 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1% PEG 8000, 1.7 U/ml human plasma thrombin, test compounds, and 20 μM substrate (benzoyl-Phe-Val-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin). Analysis of kallikrein inhibition was performed in reaction mixtures containing 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, 2 nM human plasma kallikrein, test compounds, and 50 μM substrate (benzyloxycarbonyl-Phe-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin). Analysis of urokinase inhibition assay was performed in reaction mixtures containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 30 U/mL human urine urokinase, test compounds, and 30 μM substrate (benzyloxycarbonyl-Gly-Gly-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin). Analysis of cathepsin D inhibition was performed in reaction mixtures containing 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 0.1 U/mL human spleen cathepsin D, test compounds, and 5 μM substrate (MOCAc-Gly-Lys-Pro-Ile-Leu-Phe-Phe-Arg-Leu-Lys(Dnp)-D-Arg-NH2). Cathepsin D assays were monitored with a Fluoroskan Ascent FL microtiter plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 340 and 390 nm, respectively. For all serine proteases (chymotrypsin, thrombin, kallikrein, and urokinase), activity was monitored at excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 460 nm, respectively. For all compounds tested, the concentration of inhibitor that caused 50% inhibition of the enzymatic reaction (IC50) was calculated by plotting % inhibition vs logarithm of inhibitor concentration (at least six points), and the data are the mean values of at least three experiments with relative standard deviations of <15%.

Analysis of Compound Stability

Spontaneous hydrolysis of selected indazole derivatives was evaluated at 25 °C in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.3. Kinetics of hydrolysis were monitored by measuring changes in absorbance spectra over time using a SpectraMax Plus microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Absorbance (At) at the characteristic absorption maxima of each N-benzoylpyrazole was measured at the indicated times until no further absorbance decreases occurred (A∞).43 Using these measurements, we created semilogarithmic plots of log(At – A∞) vs time and k’ values were determined from the slopes of these plots. Half-conversion times were calculated using t½ = 0.693/k’, as described previously.25

Molecular Modeling

For molecular modeling, we used HyperChem 7.0 (Hypercube Inc., Waterloo, ON, Canada) and Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD), version 4.2.0 (CLC bio, Denmark) software. Molecular structures of compounds 5b, 5d, 8, 14f, 26b, and 31h were generated in HyperChem and optimized with the use of the semi-empirical PM3 method. These structures were then saved in the Tripos Mol2 format and imported into the MVD program for docking into the HNE binding site.

The structure of HNE complexed with a peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor41 was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (1HNE entry of the database). The search area for docking poses was defined as a sphere with 10 Å radius centered at the nitrogen atom in the five-membered ring of the peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor. After removal of this peptide and co-crystallized water molecules from the program workspace, we set sidechain flexibility for 42 residues closest to the center of the search area (His40, Phe41, Cys42, Gly43, Ala55, Ala56, His57, Cys58, Val59, Ala60, Tyr94, Pro98, Asn99A, Leu99B, Asp102, Trp141, Gly142, Leu143, Leu167, Arg177, Val190, Cys191, Phe192, Gly193, Asp194, Ser195, Gly196, Ser197, Ala213, Ser214, Phe215, Val216, Arg217A, Gly218, Gly219, Cys220, Ser222, Leu223, Tyr224, Asp226, Ala227, Phe228). To simulate the receptor flexibility, the standard technique built in the Molegro program was employed, i.e. docking a ligand with softened potentials was followed by optimization of flexible sidechains with respect to the found pose. Further simultaneous minimization of these sidechains and the pose using non-softened potentials was applied [Molegro Virtual Docker. User manual, 2010]. Values of 0.9 and 0.7, respectively, were assigned to the “Tolerance” and “Strength” parameters of the MVD “Sidechain Flexibility” wizard. Fifteen docking runs were performed for each compound, with full flexibility of a ligand around all rotatable bonds and sidechain flexibility of the selected residues of the enzyme (see above).

The docking poses corresponding to the lowest-energy binding mode of each inhibitor were evaluated for the ability to form a Michaelis complex between the hydroxyl group of Ser195 and the carbonyl group in the amido moiety of an inhibitor. For this purpose, values of d1 [distance O(Ser195)…C between the Ser195 hydroxyl oxygen atom and the carbonyl carbon atom of the amido moiety] and α [angle O(Ser195)…C=O, where C=O is the carbonyl group of an inhibitor amido moiety] were determined for each docked compound44 (Supplemental Figure S1). In addition, we estimated the possibility of proton transfer from Ser195 to Asp102 through His57 (the key catalytic triad of serine proteases41,45,46) by calculating distances d2 between the NH hydrogen in His57 and carboxyl oxygen atoms in Asp102. The distance between the hydroxyl proton in Ser195 and the pyridine-type nitrogen in His57 is also important for proton transfer. However, because of easy rotation of the hydroxyl about the C–O bond in Ser195, we measured distance d3 between the oxygen in Ser195 and the basic nitrogen atom in His57. The effective length L of the channel for proton transfer was calculated as L=d3+min(d2).

Supplementary Material

Scheme 3.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number GM103500, an equipment grant from the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust, and the Montana State University Agricultural Experimental Station.

Abbreviation used

- HNE

human neutrophil elastase

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- His

histidine

- Asp

aspartic acid

- Ser

serine

- Cys

cysteine

- S.D.

standard deviation

- N.A.

not active

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Chemical and physical characteristics and spectral data for all the remaining new intermediates 5c, 5e, 14f-h, 20c, 20d-f, 26f-h, 31c-g, 31i. Elemental analyses for all final new compounds. Supplemental Figures S1 and S2 and their legends.

This material is available free of charge via the internet at htpp://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Travis J, Dubin A, Potempa J, Watorek W, Kurdowska A. Neutrophil proteinases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991;624:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou X, Dai Q, Huang X. Neutrophils in acute lung injury. Front. Biosci. 2012;17:2278–2283. doi: 10.2741/4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha S, Watorek W, Karr S, Giles J, Bode W, Travis J. Primary structure of human neutrophil elastase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:2228–2232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockley RA. Neutrophils and protease/antiprotease imbalance. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;160:49–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heutinck KM, ten Berge IJ, Hack CE, Hamann J, Rowshani AT. Serine proteases of the human immune system in health and disease. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:1943–1955. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannino DM. Epidemiology and global impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Semin. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2005;26:204–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, CherniacK RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Parè PD. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Donnell R,A, Peebles C, Ward JA, Daraker A, Angco Broberg, P., Pierrou S, Lund J, Holgate ST, Davies DE, Delany DJ, Wilson SJ, Djukanovic R. Relationship between peripheral airway dysfunction, airway obstruction and neutrophilic inflammation in COPD. Thorax. 2004;59:837–842. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straubaugh SD, Davis PB. Cystic fibrosis: a review of epidemiology and pathology. Clin. Chest Med. 2007;28:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dollery CM, Owen CA, Sukhova GK, Krettek A, Shapiro SD, Libby P. Neutrophil elastase in human atherosclerotic plaques: production by macrophages. Circulation. 2003;107:2829–2836. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072792.65250.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen PA, Sallenave J-M. Human neutrophil elastase: mediator and therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B. 2008;40:1095–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawabata K, Moore AR, Willoughby DA. Impaired activity of protease inhibitors towards neutrophil elastase bound to human articular cartilage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1996;55:248–252. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiedow O, Wiese F, Streit V, Kalm C, Cristopher E. Lesional elastase activity in psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis. Invest. Dermatol. 1992;99:306–309. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanrajani PJ. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: clinical presentation and a brief review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Ora. Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2009;108:187. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moroy G, Alix AJ, Sapi J, Hornebeck W, Bourguet E. Neutrophil elastase as a target in lung cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:565–579. doi: 10.2174/187152012800617696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohbayashi H. Novel neutrophil elastase inhibitors as a treatment for neutrophil-predominant inflammatory lung diseases. IDrugs. 2002;5:910–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong J, Groutas WC. Recent developments in the design of mechanism-based and alternate substrate inhibitors of serine proteases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004;4:1203–1216. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly E, Greene CM, McElvaney NG. Targeting neutrophil elastase in cystic fibrosis. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2008;12:145–157. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groutas WC, Dou D, Alliston KR. Neutrophil elastase inhibitors. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2011;21:339–354. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.551115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjö P. Neutrophil elastase inhibitors: recent advances in the development of mechanism-based and nonelectrophilic inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2012;4:651–660. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwata K, Doi A, Ohji G, Oka H, Oba Y, Takimoto K, Igarashi W, Gremillion DH, Shimada T. Effect of neutrophil elastase inhibitor (Sivelestat sodium) in the treatment of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory di stress (ARDS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern. Med. 2010;49:2423–2432. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawabata K, Suzuki M, Sugitani M, Imaki K, Toda M, Miyamoto T. ONO-5046, a novel inhibitor of human neutrophil elastase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;177:814–820. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stockley R, De Soyza A, Gunawardena K, Perrett J, Forsman-Semb K, Entwistle N, Snell N. Phase II study of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor (AZD9668) in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir. Med. 2013;107:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelmeier C, Aquino TO, O’Brien CD, Perrett J, Gunawardena KA. A randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study of AZD9668, an oral inhibitor of neutrophil elastase, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with tiotropium. COPD. 2012;9:111–120. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.641803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crocetti L, Giovannoni MP, Schepetkin IA, Quinn MT, Khlebnikov AI, Cilibrizzi A, Dal Piaz V, Graziano A, Vergelli C. Design, synthesis and evaluation of N-bezoylindazole derivatives and analogues as inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:4460–4472. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khlebnikov AI, Schepetkin IA, Quinn MT. Structure-activity relationship analysis of N-benzoylpyrazoles for elastase inhibitory activity: a simplified approach using atom pair descriptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:2791–2802. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Quinn MT. N-benzoylpyrazoles are novel small molecule inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4928–4938. doi: 10.1021/jm070600+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stadlbauer W. Product class 2: 1H- and 2H-indazoles. Science of Synthesis. 2002;12:227–324. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piozzi F, Ronchi AU. Synthesis of substituted 3-indazole ketones. Gazzetta Chimica Italiana. 1963;93:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foloppe N, Fisher LM, Francis G, Howes R, Kierstan P, Potter A. Identification of a buried pocket for potent and selective inhibition of Chk1: prediction and verification. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:1792–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shatalov GV, Preobrazhenskii SA, Mikhant’ev BI. New highly active monomers with pyrazole and indazole rings. Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved., Khim. Khim. Tekhnol. 1977;20:2928–293. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bistocchi GA, De Meo G, Pedini M, Ricci A, Brouilhet H, Boucherie S, Rabaud M, Jacquignon P. N1-substituted 1H-indazole-3-ethyl carboxylates and 1H-indazole-3-hydroxamic acids. Il Farmaco. 1981;36(5):315–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchstaller HP, Wilkinson K, Burek K, Nisar Y. Synthesis of 3-indazolecarboxylic esters and amides via Pd-catalyzed carbonylation of 3-iodoindazoles. Synthesis. 2011;19:3089–3098. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie W, Herbert B, Schumacher R, Ma J, Nguyen TM, Gauss CM, Yehim A. 1H-indazoles, benzothiazoles, 1,2-benzoisoxazoles, 1,2-benzoisothiazoles, and choromones and preparation and uses thereof. PCT Int. Appl. 2005 WO111038A2. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder HR, Thompson CB, Hinman RL. The synthesis of an indazole analog of DL-tryptophan. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:2009–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Somasekhara S, Dighe VS, Suthar GK, Mukherjee SL. Chlorosolfonation of isatins. Current Science. 1965;34(17):508. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buu-Hoi NP, Hoeffinger JP, Jacquignon P. Indazole-3-carboxylic acids and their derivatives. J. Het. Chem. 1964;1(5):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schumacher R, Danca MD, Ma J, Herbert B, Nguyen TM, Xie W, Tehim A. Preparation of azabicyclic derivatives of indazoles, benzothiazoles, benzoisothiazoles, benzisoxazoles, pyrazolopyridines, isothiazolopyridines for therapeutic use as α7-nACh receptor activators. PCT Int. Appl. 2007 WO 2007038367 A1 20070405. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie W, Herbert B, Ma J, Nguyen TM, Schumacher R, Gauss CM, Tehim A. Indoles, 1H-indazoles, 1,2-benzisoxazoles, and 1,2-benzisothiazoles, and preparation and uses thereof. PCT Int. Appl. 2005 WO 2005063767 A2 20050714. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savitskaya NV, Tarasevich ES, Shchukina MN. Some derivatives of 5-nitro and 5-amino-3-indazolecarboxylic acid. Zhurnal Obshchei Khimii. 1961;31:3255–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navia MA, McKeever BM, Springer JP, Lin TY, Williams HR, Fluder EM, Dorn CP, Hoogsteen K. Structure of human neutrophil elastase in complex with a peptide chloromethyl ketone inhibitor at 1.84 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:7–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgi HB, Dunitz JD, Lehn JM, Wipff G. Stereochemistry of reaction paths at carbonyl centers. Tetrahedron. 1974;30:1563–1572. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vergely I, Laugaa P, Reboud-Ravaux M. Interaction of human leukocyte elastase with a N-aryl azetidinone suicide substrate: conformational analyses based on the mechanism of action of serine proteinases. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(96)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters MB, Merz KM. Semiempirical comparative binding energy analysis (SE-COMBINE) of a series of trypsin inhibitors. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006;2:383–399. doi: 10.1021/ct050284j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dodson G, Wlodawer A. Catalytic triads and their relatives. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:347–352. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]