Abstract

In March 2013, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported human infections with an H7N9 influenza virus, and by 20 July 2013, the numbers of laboratory-confirmed cases had climbed to 134, including 43 fatalities and 127 hospitalizations. The newly emerging H7N9 viruses constitute an obvious public health concern because of the apparent severity of this outbreak. Here we focus on the hemagglutinins (HAs) of these viruses and assess their receptor binding phenotype in relation to previous HAs studied. Glycan microarray and kinetic analyses of recombinant A(H7N9) HAs were performed to compare the receptor binding profile of wild-type receptor binding site variants at position 217, a residue analogous to one of two positions known to switch avian to human receptor preference in H2N2 and H3N2 viruses. Two recombinant A(H7N9) HAs were structurally characterized, and a mutational study of the receptor binding site was performed to analyze important residues that can affect receptor preference and affinity. Results highlight a weak human receptor preference of the H7N9 HAs, suggesting that these viruses require further adaptation in order to adapt fully to humans.

INTRODUCTION

Annually, influenza viruses pose a serious global public health risk as they can infect up to 20% of the human population. In the United States alone, estimates of influenza-associated deaths range from 3,000 to 49,000 per annum (1). In the last century, three influenza virus subtypes have successfully adapted to the human population, causing four pandemics, H1N1 in 1918 and most recently 2009, H2N2 in 1957, and H3N2 in 1968 (2–4). Other subtypes are prevalent in domestic poultry in certain parts of the world (e.g., H5N1, H6N1, H7N2, and H9N2 [5]) and are considered to have pandemic potential by public health officials.

Indeed, a number of recent outbreaks in poultry involving viruses from H5, H7, and H9 subtypes have resulted in ∼800 human infections. However, their low transmissibility among humans has thus far prevented an epidemic (6–8). Since 1979 (9), there has been sporadic reporting of human H7 infections with both low-pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and high-pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H7 viruses of Eurasian and North American lineages (10–20). Until this year, the largest outbreak, an HPAI H7N7 virus in 2003 in the Netherlands, resulted in 89 human infections, including one fatality and three cases of possible human-to-human virus transmission (14).

On 31 March 2013, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first three reported cases of human infection with an avian influenza A(H7N9) virus to the World Health Organization (21). As of 20 July 2013, 134 cases of infection with the A(H7N9) virus were laboratory confirmed with cases being characterized by severe pulmonary disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) causing 43 fatalities (22). While there is no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission, reports of family clusters of H7N9 infection suggest the potential for virus spread between close contacts (23). Understanding the molecular properties of H7N9 influenza viruses and the contribution of each viral protein to human disease are critical requirements for guiding public health responses to current and future outbreaks. Here, we characterize the influenza virus coat protein hemagglutinin (HA), which binds to host cell surface glycan receptors containing sialic acid (SA) and subsequently mediates virus uptake, membrane fusion, and infection. HA is the primary antigen involved in the host immune response to viral infection.

Whereas human seasonal influenza viruses bind to host receptors containing α2-6-linked SA, avian influenza viruses predominantly bind to receptors containing α2-3-linked SA (24, 25). Previous studies on human-adapted H3N2 viruses identified a number of key receptor binding site (RBS) mutations that were responsible for switching avian/human receptor specificity. Two mutations, Gln226Leu and Gly228Ser correlated with a shift to human receptor specificity (25, 26). Interestingly, as of late June 2013, 84% of all HA sequences derived from H7N9 viruses isolated from humans and deposited in the GISAID database (http://www.gisaid.org) possessed a Gln217Leu change, which is equivalent to residue 226 in H3 HAs (Gln226Leu).

In an attempt to better understand the molecular characteristics of these recent HAs in relation to our previous work with the A/Netherlands/219/2003 A(H7N7) HA (NL219) and the recent A(H1N1)pdm09 virus HA (27, 28), we have determined the three-dimensional atomic structures of two 2013 A(H7N9) HAs: A/Shanghai/1/2013 (SH-1), which has Gln217, and A/Shanghai/2/2013 (SH-2), which possesses Leu217. We have analyzed the receptor specificity of these recombinant HA (recHA) proteins using both glycan microarrays and Bio-Layer Interferometry and compared differences in the RBS to the older A(H7N7) NL219 HA RBS. These results also led us to determine the structures of both HAs in complex with the glycan LS-tetrasaccharide b (LSTb). Our studies highlight the following: (i) an RBS with weaker binding to glycan microarrays than H7N7, which suggests that further adaptation and optimization to bind human receptors are required to fully switch these HAs to a specific human receptor preference, and (ii) a level of instability with these HAs, similar to what was observed with early A(H1N1)pdm09 HAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning.

DNA encoding residues 1 to 497 of the mature hemagglutinin (HA) ectodomain from influenza A/Shanghai/1/2013 (H7N9) (SH-1) and A/Shanghai/2/2013 (SH-2) viruses was cloned into the baculovirus transfer vector, pAcGP67-B (BD Biosciences), in frame with an N-terminal baculovirus GP67 signal peptide and a C-terminal thrombin cleavage site, a “foldon” sequence (29) and a hexahistidine tag at the extreme C terminus of the fusion protein to enable purification (30). For these studies, we also utilized previously described H7 HA proteins, A/New York/107/2003 (NY107) (31), A/Netherlands/219/2003 (NL219) and an HA mutant (Thr125Ala) lacking a glycosylation motif at Asn123 (NL219-T125A) (28). All mutations described here (Table 1), including the construct for A/Hangzhou/1/2013 (H7N9) (HGZ-1), were generated by mutagenizing wild-type constructs using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). Transfection and virus amplification were carried out according to the Baculovirus Expression System Manual (32).

Table 1.

Recombinant HA proteins and mutations used in this study

| Influenza virus strain | Virus subtype | GISAID database entry | Mutation(s)a | Name used here |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Shanghai/1/2013 | H7N9 | EPI439486 | None (WT) | SH-1 |

| A/Shanghai/2/2013 | H7N9 | EPI439502 | None (WT) | SH-2 |

| G219S | SH-2 G219S | |||

| A/Hangzhou/1/2013 | H7N9 | EPI440095 | None (WT) | HGZ-1 |

| A/Netherlands/219/2003 | H7N7 | EPI234814 | None (WT) | NL219 |

| T125A | ||||

| T125A, Q217L | ||||

| T125A, Q217I | ||||

| T125A, G177V Q217L | ||||

| T125A, T180A, Q217L | ||||

| T125A, G177V, T180A, Q217L | ||||

| T125A, G177V, T180A, Q217I | ||||

| T125A, Q217L, G219S | ||||

| T125A, Q217I, G219S | ||||

| G177V, T125A, Q217L, G219S | ||||

| T125A, T180A, Q217L, G219S | ||||

| T125A, G177V, T180A, Q217L, G219S | ||||

| T125A, G177V, T180A, Q217I, G219S | ||||

| A/New York/107/2003 | H7N2 | EPI141612 | None (WT) | NY107 |

| A/Hong Kong/1/1968 | H3N2 | EPI240947 | None (WT) | HK68 |

| A/California/7/2009 | H1N1pdm | EPI177294 | None (WT) | CA709 |

| A/Vietnam/1203/2004 | H5N1 | EPI361524 | None (WT) | Viet04 |

WT, wild type.

Protein expression and purification.

Soluble HA trimers were purified from the culture supernatant by metal affinity chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. For structural analyses, SH-1 and SH-2 HA proteins were subjected to thrombin digestion as described previously (31), buffer exchanged into 10 mM Tris-HCl and 50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0), and concentrated to 17 mg/ml for crystallization trials. At this stage, both the H7 HA proteins contained additional plasmid-encoded residues at both the N terminus (ADPG) and C terminus (SGRLVPR).

Ability to maintain functional trimers in solution.

Recombinant protein was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with biotinylated thrombin (Novagen) at a ratio of 3 units per mg recHA. The sample was then subjected to size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a suitable Superdex-200 column (GE Healthcare) with 50 mM Tris-HCl and 100 mM NaCl (pH 8) as the running buffer.

Crystallization, ligand soaking, and data collection.

Initial nanoscale crystallization trials were completed using a Topaz free interface diffusion (FID) crystallizer system (Fluidigm Corporation, San Francisco, CA). Crystals were observed in several conditions containing polyethylene glycol 3350 (PEG 3350) and PEG 4000. Following optimization, diffraction quality crystals for SH-1 HA were obtained at 20°C using a modified method for microbath under oil (33), by mixing the protein with a reservoir solution containing 0.2 M MgCl2, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and 16% PEG 4000. Similarly, SH-2 HA was crystallized in a solution containing 0.2 M CaCl2 and 20% PEG 3350. For receptor analog complexes, crystals were soaked overnight in the crystallization buffer containing 10 mM LSTb (V-Labs Inc., Covington, LA). Data sets were collected at the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source (APS) beamline 22 ID at 100K. Data were processed with the DENZO-SCALEPACK suite (34). Statistics on data collection are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for both SH-1 and SH-2 crystal structures and complexes

| Parameter | Value(s)a for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH-1 | SH-1/LSTb complex | SH-2 | SH-2/LSTb complex | |

| Data collection statistics | ||||

| Space group | P21 21 21 | P21 21 21 | P21 21 21 | P21 21 21 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | 154.30, 154.29, 154.93 | 154.01, 153.96, 153.52 | 154.02, 152.83, 155.30 | 154.36, 154.44, 154.06 |

| Cell angle (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.65 (2.72–2.65) | 50–3.10 (3.18–3.10) | 50–2.15 (2.21– 2.15) | 50–2.50 (2.57–2.50) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.085 (0.835) | 0.106 (0.884) | 0.104 (0.835) | 0.099 (0.809) |

| I/σ | 36.7 (2.4) | 23.7 (1.8) | 20.1 (3.2) | 25.7 (1.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.5 (97.7) | 99.9 (99.7) | 98.2 (90.5) |

| Redundancy | 7.0 (6.9) | 6.8 (5.9) | 7.0 (5.3) | 5.9 (3.5) |

| Refinement statistics | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.65 (2.72–2.65) | 50–3.10 (3.18–3.10) | 50–2.15 (2.21–2.15) | 50–2.50 (2.57–2.50) |

| No. of reflections (total) | 763,318 | 541,166 | 1,394,574 | 745,119 |

| No. of reflections (unique) | 107,646 | 66,487 | 201,333 | 125,200 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.211/0.244 | 0.200/0.243 | 0.238/0.259 | 0.217/0.246 |

| No. of atoms | 23,076 | 22,947 | 23,248 | 23,839 |

| RMSD | ||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.014 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.64 | 1.59 | 1.86 | 1.62 |

| MolProbity scoresb | ||||

| Favored (%) | 95.3 | 94 | 97 | 97 |

| Outliers (%) (no. of residues)c | 0.2 (6/2,952) | 0.5 (16/2,916) | 0.2 (6/2,930) | 0.2 (6/2,954) |

| PDB accession no. | 4LN3 | 4LN4 | 4LN6 | 4LN8 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell unless specified otherwise.

Data from Davis et al. (35).

For the outlier values, the numbers in parentheses are the number of outlier residues and the total number of residues.

Structure determination and refinement.

The structures of SH-1 and SH-2 were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser (36) using the previously published NL219 HA, Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession no. 4DJ6 (HA1, 95% identity for SH-1 and 96% for SH-2; HA2, 98% identity for SH-1 and 97% for SH-2) as search model (28). Two HA trimers occupy the asymmetric unit with an estimated solvent content of 56.4% and 56.2% based on a Matthews' coefficient (Vm) of 2.82 Å3/Da and 2.80 Å3/Da for SH-1 and SH-2, respectively. Rigid body refinement of the trimer led to an overall R/Rfree of 31.1/35.3 and 34.1/38.9 for SH-1 and SH-2, respectively. All model building and refinement were performed using Coot (37), Phenix (38), as well as REFMAC5 (39) using TLS (translation/libration/screw) refinement (40). Model validation was carried out using MolProbity (35). All statistics for data processing and refinement are presented in Table 2. As with our previous publication (28), unless specified otherwise, all residue numbering will be according to the mature H7 protein.

Glycan binding analyses.

Glycan microarray printing and recombinant HA analyses have been described previously (28, 31, 41–44). Table 3 lists glycans used in these experiments as well as a tabulated qualitative assessment of binding for each protein analyzed. For kinetic studies, biotinylated glycans, Neu5Ac(α2-3)Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc(β1-3)Gal(β1-4)GlcNAcb-biotin (3SLNLN-b) and Neu5Ac(α2-6)Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc(β1-3)Gal(β1-4)GlcNAcb-biotin (6SLNLN-b), obtained from the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (www.functionalglycomics.org) through the resource request program, were coupled to streptavidin-coated biosensors (Fortebio Inc.). Recombinant HA was diluted to 5.4 μM trimer in kinetics buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.02% Tween 20, 0.005% sodium azide, and 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin), and binding was analyzed by biolayer interferometry (BLI) on an Octet red instrument (Fortebio Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were analyzed using the system software and fitted to a 1:1 binding model.

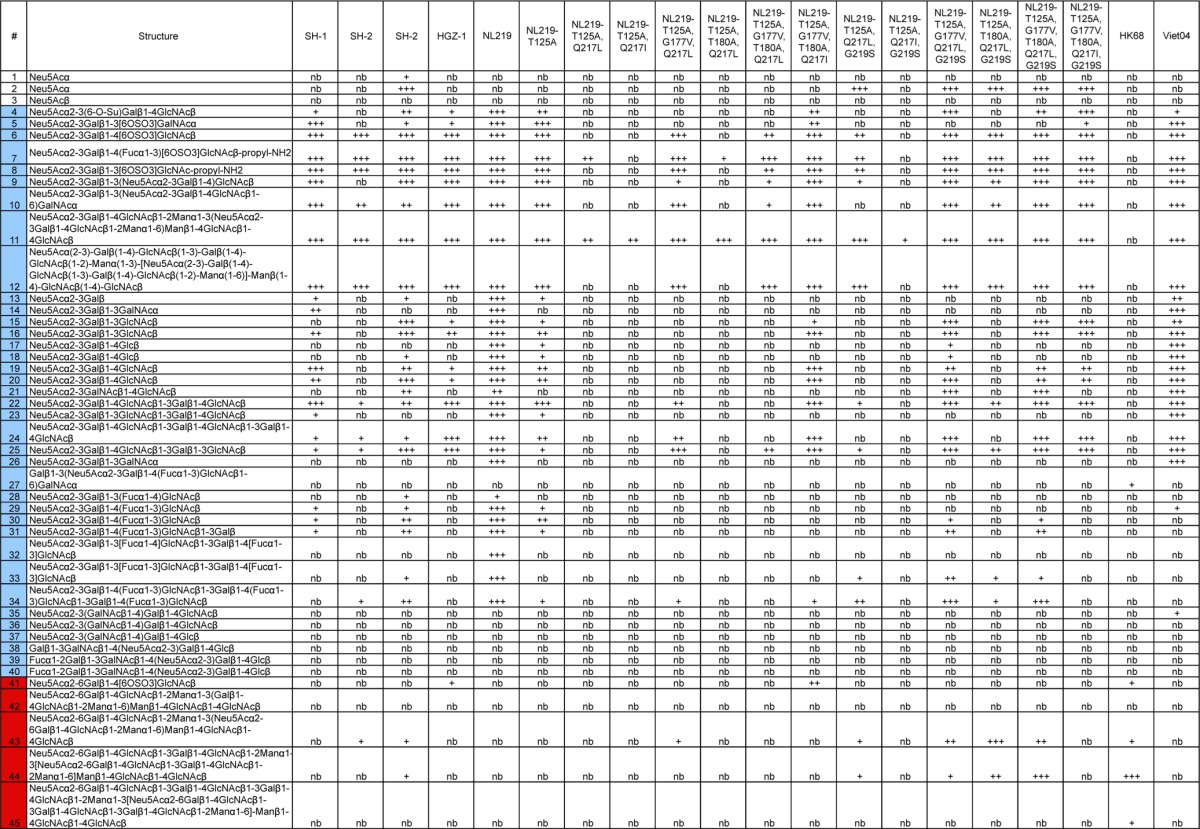

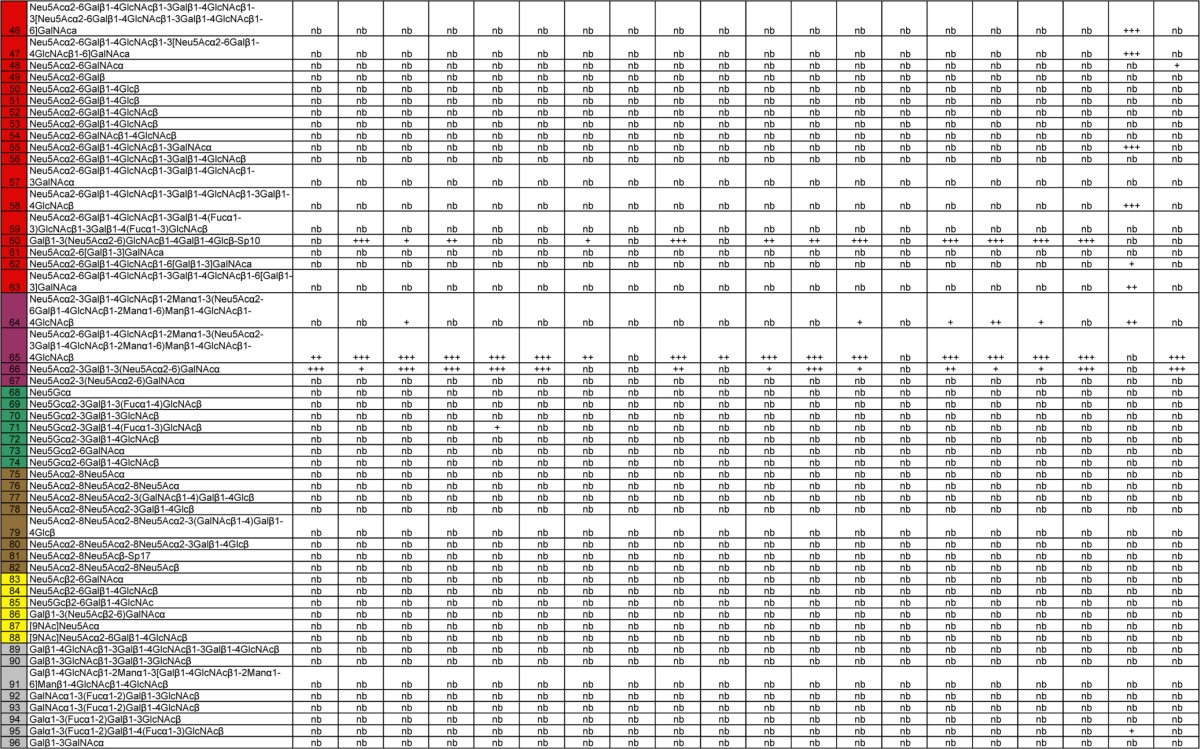

Table 3.

Glycan array differences between H7N9 wild-type and mutant recHAs analyzed in this studya

The leftmost column shows the glycan number. Different categories of glycans on the array are color coded in the leftmost column as follows: no color, sialic acid; blue, α2-3 sialosides; red, α2-6 sialosides, violet, mixed α2-3/α2-6 biantennaries; green, N-glycolylneuraminic acid-containing glycans; brown, α2-8-linked sialosides; yellow, β2-6-linked and 9-O-acetylated sialic acids; gray, asialo glycans. The structures of the glycans are shown next. The remaining columns show binding to the glycans. Significant binding of samples to glycans was qualitatively estimated based on the relative strength of the signal for the data. Symbols: +, relative fluorescence intensity of 3,001 to 9,999; ++, relative fluorescence intensity of 10,000 to 19,999; +++, relative fluorescence intensity of >20,000; nb, no binding or relative fluorescence intensity of <3,000.

Protein structure accession numbers.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of SH-1 and SH-2 HA and their LSTb complexes are available from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) PDB under accession nos. 4LN3, 4LN4, 4LN6, and 4LN8.

RESULTS

Recombinant HA production/stability.

Soluble recombinant HA (recHA) ectodomains were expressed in an established baculovirus expression system (30). In the absence of a trans-membrane domain, trimeric protein was obtained by fusing recHA to a C-terminal cassette containing a thrombin cleavage site and a trimerization domain (foldon) (29). By size exclusion chromatography (SEC), seasonal as well as avian virus HAs usually elute as trimeric species of ∼200 kDa upon removal of the trimerization domain (foldon) following proteolytic cleavage with thrombin (28, 31, 44). However, SH-2 influenza A(H7N9) virus recHA eluted as ∼70-kDa monomers, while SH-1 revealed a mixed trimer/monomer population (data not shown). This inability to maintain a trimeric state was also observed in previous studies with early A(H1N1)pdm09 virus recHAs, and although monomers were produced, the recHA protein was still able to form trimers in subsequent crystals, which enabled structural analysis (27).

Structural overview of SH-1 and SH-2 recHAs.

In order to study these HAs from a structural perspective, we expressed these proteins in a recombinant baculovirus expression system (30). While a trimeric fraction of SH-1 was obtained for crystallization studies, SH-2 was purified as a monomer. However, as with the early influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus recHAs (27), SH-2 still crystallized, and both three-dimensional trimeric HA structures were determined by X-ray crystallography to 2.65-Å (SH-1) and 2.15-Å (SH-2) resolution (Table 2).

The overall structures of SH-1 and SH-2 were similar to those of previously reported H7 HAs as well as to those of other subtypes (27, 28, 31, 43–50). To assess structural variation among these HAs, we compared the HA1/HA2 protomer of SH-1 and SH-2 to each other as well as to other published HAs. All Cα atoms in the HA1/HA2 protomer of SH-1 and SH-2 superimposed with each other to give root mean square deviations (RMSDs) of only 0.44 Å. Superimposition onto other HAs showed better structural homology to other H7 (NL219) and group 2 HAs compared to the group 1 examples analyzed (Table 4). Five asparagine-linked glycosylation sites are predicted in both SH-1 and SH-2 HA monomers. For SH-1 only, Asn28, Asn231 in HA1, and Asn82 in HA2 have interpretable carbohydrate electron density, whereas for SH2, Asn12, Asn28, and Asn231 in HA1 and Asn82 in HA2 have interpretable carbohydrate electron density (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, while Asn154 in HA2 is conserved in all subtypes, Asn82 is present only in H7, H10, and H15 subtypes.

Table 4.

Comparison of RMSD values for HA1 and HA2 domainsa

| Group | Host-subtypeb | Influenza virus strain | PDB accession no. | RMSD (Å) valuesc for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | HA1 RBS domain | HA2 domain | ||||

| 1 | Hu-H1N1 | A/Darwin/2001/2009 | 3M6S | 3.18/3.26 | 0.95/0.91 | 2.66/2.70 |

| Hu-H2N2 | A/Japan/305/1957 | 3KU5 | 3.13/3.28 | 1.09/1.07 | 2.93/2.96 | |

| Hu-H5N1 | A/Vietnam/1203/2004 | 2FK0 | 3.27/3.33 | 0.87/0.92 | 2.75/2.81 | |

| Sw-H9N2 | Swine/Hong Kong/9/1998 | 1JSD | 3.38/3.45 | 0.87/0.86 | 3.00/3.02 | |

| 2 | Hu-H3N2 | A/Hong Kong/1/1968 | 2HMG | 2.00/2.23 | 1.13/1.16 | 2.31/2.34 |

| Hu-H7N7 | A/Netherlands/219/2003 | 4DJ6 | 1.56/1.92 | 0.53/0.49 | 1.89/1.92 | |

| Av-H7N3 | A/turkey/Italy/2002 | 1TI8 | 1.48/1.84 | 0.64/0.58 | 1.92/1.94 | |

| Av-H14N5 | A/mallard/Astrakhan/263/1982 | 3EYK | 2.28/2.47 | 1.26/1.24 | 2.35/2.38 | |

| Mean RMSD between SH-1 and SH-2 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.38 | |||

For analyzing differences in different HA monomers, RMSD values were calculated after the Cα atoms of the HA2 domains were superposed by sequence and structural alignment onto the equivalent domains of SH-1/SH-2 HAs.

The host is shown before the hyphen, and the subtype is shown after the hyphen. Abbreviations: Hu, human; Sw, swine, Av, avian.

RMSD values for SH-1 are listed first before the slashes, and RMSD values for SH-2 are listed after the slashes.

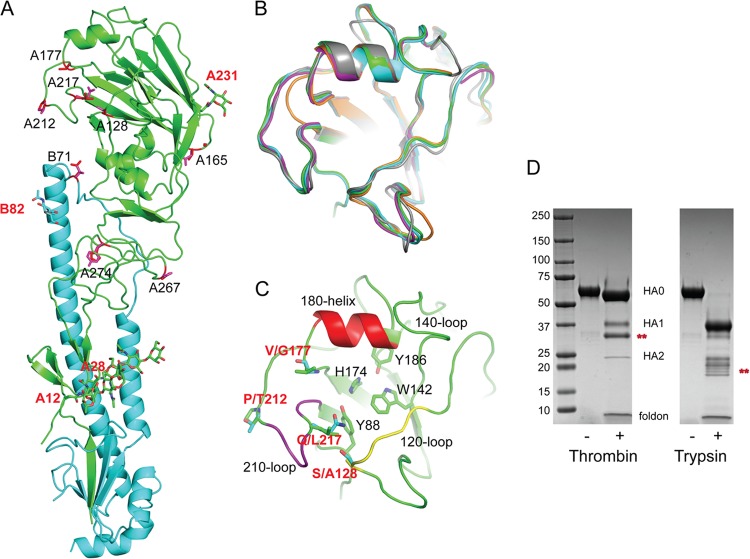

Fig 1.

Structural overview of SH-2 HA monomer. (A) One SH-2 monomer is shown with the HA1 chain colored in green and the HA2 chain in cyan. The locations of the glycosylation sites are labeled in red. The sequence differences between SH-1 and SH-2 are indicated in the figure as red sticks. (B) RBS overlap of SH-2 (green), SH-1 (cyan), NL219 (magenta) (PDB accession no. 4DJ6), NY107 (orange) (PDB accession no.3M5G), and human H3 (gray) (PDB accession no. 2HMG). All structural figures were generated with MacPyMol (62). (C) RBS of SH-2 with the three structural elements comprising this binding site, the 210-loop, 120-loop, and 180-helix, colored purple, yellow, and red, respectively. Conserved residues are shown as sticks. RBS residue differences between SH-1 and SH-2 are also shown as sticks and labeled in red. (D) SDS-PAGE of SH-2 recHA before (−) and after (+) treatment with thrombin and trypsin. Bands labeled with red asterisks are unaccounted for. The positions (in kilodaltons) of molecular mass standards are shown to the left of the gel.

The structure of the receptor binding site (RBS) from SH-1 and SH-2 is similar to all influenza A virus HAs (Fig. 1B). They are composed of three structural elements: a 180-helix (positions 178 to 186), 210-loop (positions 211 to 219), and 120-loop (positions 123 to 128) (Fig. 1C). At the base of the pocket, four highly conserved residues Tyr88, Trp143, His174, and Tyr186 (equivalent to Tyr98, Trp153, His183, and Tyr195 in H3 numbering) are present and conserved in these recent HAs (Fig. 1C). Similar to previous structural analyses of H7 HAs (31, 48), a two-amino-acid insertion in the nearby 140-loop produces an ∼6-Å movement of both the SH-1 and SH-2 140-loops toward the RBS compared to a group 2 A(H3N2) HA (Fig. 1B and C).

Fusion peptide cleavage site.

During infection and viral replication, HA is synthesized as a single-chain precursor (HA0) and is cleaved by a specific host protease into the infectious HA1 and HA2 form. While highly pathogenic viruses, such as H5N1 as well as certain H7 viruses, possess a polybasic cleavage site that can be cleaved by a number of other serine proteases, these current H7 HAs do not, and thus are considered LPAI with respect to their cleavage sites. However, previous work with an LPAI H7 virus HA from A/New York/107/2003 (NY107) highlighted the possibility that the HA1/HA2 cleavage site (Fig. 1A) could be processed by other proteases, such as thrombin (31). Although the current 2013 H7N9 HAs also appear to have a secondary thrombin cleavage site compared to the consensus cleavage pattern in the MEROPS database (http://merops.sanger.ac.uk), results found by processing SH-2 recombinant protein for structural analyses showed that this site is not efficiently cleaved with commercially available thrombin (Fig. 1D). While most SH-2 protein maintained its HA0 form after thrombin treatment, smaller HA1/HA2 bands were visible, in addition to a stronger band migrating between two, suggesting that another thrombin-sensitive site may be present. Trypsin also efficiently cleaved HA0 to HA1 and HA2, although multiple bands were visible below the HA2 band, suggesting additional degradation (Fig. 1D).

Glycan binding analyses.

Comparison of the SH-1 and SH-2 RBS with previously published H7 HAs (PDB accession nos. 3M5G and 4DJ6) (28, 31, 48) reveals an almost identical RBS (Fig. 1D). However, sequence differences were found in the H7N9 virus HAs that suggested a putative capacity for adaptation to the human population (22). With respect to the HA, sequence analysis highlighted Leu at residue 217, a position equivalent to residue 226 in H3N2 viruses. Glycan microarray analysis of these A(H7N9) viruses confirmed that while SH-1 bearing Gln217 bound to avian α2-3 receptor analogs, the A/Anhui/1/2013 virus which has the same HA sequence as SH-2 with a Leu217, revealed a mixed α2-3/α2-6 receptor preference (51, 52).

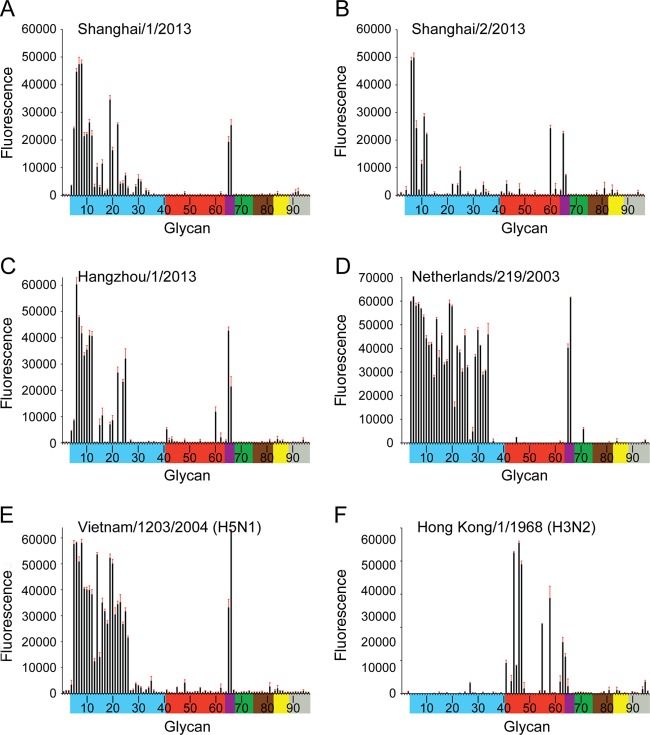

Glycan microarray analysis of recHAs provided further insight into the interactions of these influenza A(H7N9) viruses with host receptors. SH-1, SH-2, and HGZ-1 recHAs were expressed, and their binding profiles were compared to NL219 (H7), Viet04 (H5), and HK68 (H3). All three A(H7N9) HAs (Fig. 2A to C) had a more restricted binding profile to avian-type receptors compared to both the A(H7N7) NL219 (Fig. 2D) and A(H5N1) Viet04 (Fig. 2E) HA binding profiles. The strongest binding signals for SH-1 (with Gln217) were to α2-3 sulfated (glycans 5 to 8), α2-3 branched (glycans 9 to 12), and mixed α2-3/α2-6 branched sialosides (glycans 65 and 66) as well as to the linear sialyl lactosamines and dilactosamines (glycans 19, 20, and 22). SH-2, with Leu217, bound to a more restricted set of α2-3 glycans on the array including α2-3 sulfated (glycans 6 to 8), α2-3 branched (glycans 10 to 12), and mixed α2-3/α2-6 branched sialosides (glycans 65 and 66). A third recHA, HGZ-1 that differs from SH-2 only by an Leu217Ile substitution revealed a binding profile to avian-type receptors similar to SH-1. In contrast to the A(H3N2) HK68 recHA that bound specifically to human α2-6-type receptors (Fig. 2F), SH-1 yielded no signals, while both SH-2 and HGZ-1 revealed only very weak binding to human α2-6 receptors (glycans 41 to 64). Both recombinant proteins revealed a glycan binding preference to the internal structure, Galβ1-3(Neu5Acα2-6)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc (glycan 60; LSTb) (Fig. 2B and C), a glycan already highlighted in two prior studies on H7 viruses (31, 53).

Fig 2.

Glycan microarray binding analysis of wild-type H7 and H5 and H3 recombinant HAs. To assess the effect of position 217 on receptor specificity, SH-1 with Q217 (A), SH-2 with L217 (B), and HGZ-1 with I217 (C) recombinant HAs were analyzed by glycan microarray. Glycans on the microarray are grouped according to SA linkage: α2-3 SA (blue), α2-6 SA (red), α2-6/α2-3 mixed SA (purple), N-glycolyl SA (green), α2-8 SA (brown), β2-6 and 9-O-acetyl SA (yellow), and asialo glycans (gray). The reddish brown error bars in each panel reflect the standard error in the signal for six independent replicates on the array. The structures of each of the numbered glycans are found in Table 3. Specific glycan structures that were used in biosensor assays are represented on the array as glycan 22 (α2-3) and glycan 56 (α2-6).

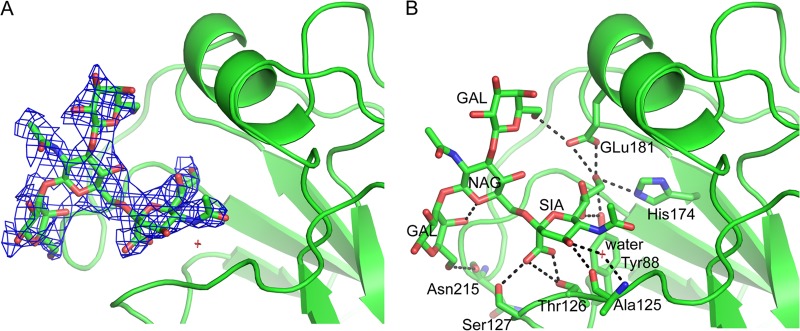

To analyze binding to this glycan, SH-1 and SH-2 complexes with LSTb were obtained for crystallization studies and their structures were solved to 3.1 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively. Although extra density was apparent in the SH-1 RBS, sialic acid could not be modeled into the density with confidence. This observation is in line with SH-1 glycan microarray results that showed no binding signals for this glycan or any other human α2-6 sialosides on the array. Also in line with microarray results (Fig. 2B), the final model for structure of the SH-2/LSTb complex contained density for much of the ligand in the RBS (Fig. 3A). Within the RBS, SA forms multiple hydrogen bonds with the side chains of Tyr88, Ala125, Thr126, Ser127, His174, and Glu181 (Fig. 3B). LSTb is further stabilized in this pocket by interaction of the linear Gal with Glu181 (180-helix), while the branched Gal interacts directly with the main-chain oxygen of Asn215 on the 210-loop (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

LSTb binding to SH-2. (A) The 2fo-fc electron density map (contoured at 1σ and shown in blue) for LSTb bound to SH-2. (B) Interactions of the LSTb glycan with the SH-2 RBS. SH-2 is shown as cartoons, while LSTb and interacting HA residues are shown as sticks. Black dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

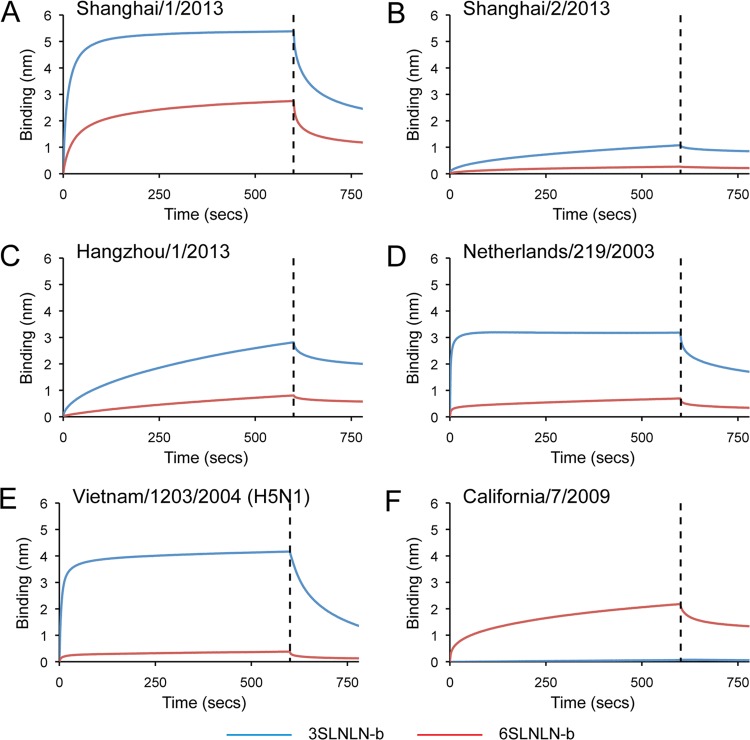

Glycan binding specificity to recombinant protein was further analyzed by biolayer interferometry (BLI) using an Octet red system (ForteBio Inc.). SH-1, SH-2, and HGZ-1 recombinant HA binding to biotinylated glycans (3SLNLN-b and 6SLNLN-b) preloaded onto streptavidin-coated biosensors was assessed (Fig. 4A, B, and C) and compared to NL219 (Fig. 4D), Viet04 (Fig. 4E), and CA709 (Fig. 4F) recHAs. While results confirm data with whole virus (51, 52) that SH-2 has weaker overall binding to avian-type receptors than SH-1 (Fig. 4A and B and Table 5), the relative instability of the SH-2 trimer as highlighted in the expression results described above may also play a role in the weak binding observed in this real-time assay. SH-1 itself also bound the human, 6SLNLN-b glycan, albeit with a 7- to 8-fold-higher off-rate (koff) compared to SH-2. Such a high off-rate could explain the lack of signals observed for this specific glycan on the array (glycan 57), which may be reduced due to the postincubation washes required to process the slides prior to scanning.

Fig 4.

The binding kinetics of recHA proteins to specific biotinylated glycans (3SLNLN-b and 6SLNLN-b) immobilized onto biosensors were analyzed by BLI. Results for binding to the human-type receptor (red) and avian-type receptor (blue) are shown. Black vertical dashed lines indicate the switch in the experiment from collecting association to dissociation data.

Table 5.

Kinetic results for glycan binding to H7, H1, and H5 RecHAsa

| HA | Glycan | Apparent KD (μM) | kon (ms−1) | kobs (mean ± SE) (×10−2 s−1) | koff (mean ± SE) (×10−2 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH-1 | 3SLNLN-b | 2.33 | 8,503 | 6.6 ± 0.06 | 2.0 ± 0.04 |

| 6SLNLN-b | 12.88 | 1,693 | 3.1 ± 0.02 | 2.8 ± 0.07 | |

| SH-2 | 3SLNLN-b | 2.36 | 2,825 | 2.2 ± 0.03 | 0.67 ± 0.014 |

| 6SLNLN-b | 1.25 | 2,648 | 2.1 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.010 | |

| HGZ-1 | 3SLNLN-b | 6.76 | 1,312 | 1.6 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.45 |

| 6SLNLN-b | 272.02 | 33 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.56 | |

| NL219 | 3SLNLN-b | 0.27 | 67,905 | 32.0 ± 0.47 | 1.83 ± 0.04 |

| 6SLNLN-b | 1.31 | 19,106 | 11.0 ± 0.27 | 2.51 ± 0.07 | |

| Viet04 | 3SLNLN-b | 0.44 | 27,208 | 12.7 ± 0.13 | 1.19 ± 0.003 |

| 6SLNLN-b | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CA709 | 3SLNLN-b | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 6SLNLN-b | 3.16 | 3,927 | 3.3 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.02 |

Abbreviations: KD, dissociation constant; kon, association rate; kobs, observed rate; koff, dissociation rate; ND, not determined due to low binding and/or no binding.

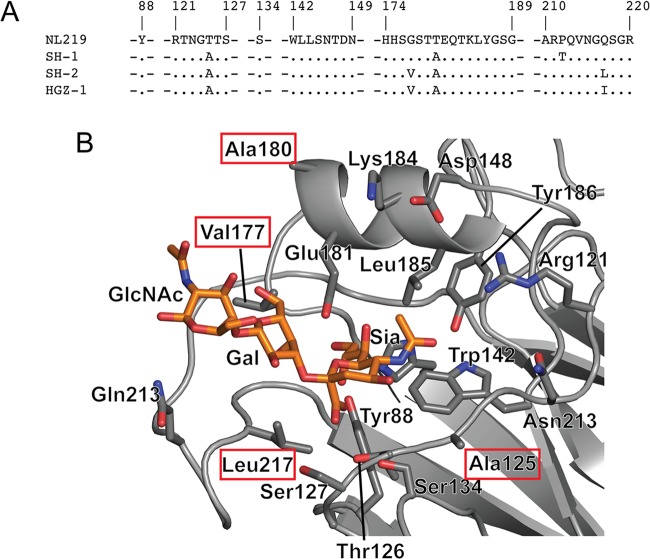

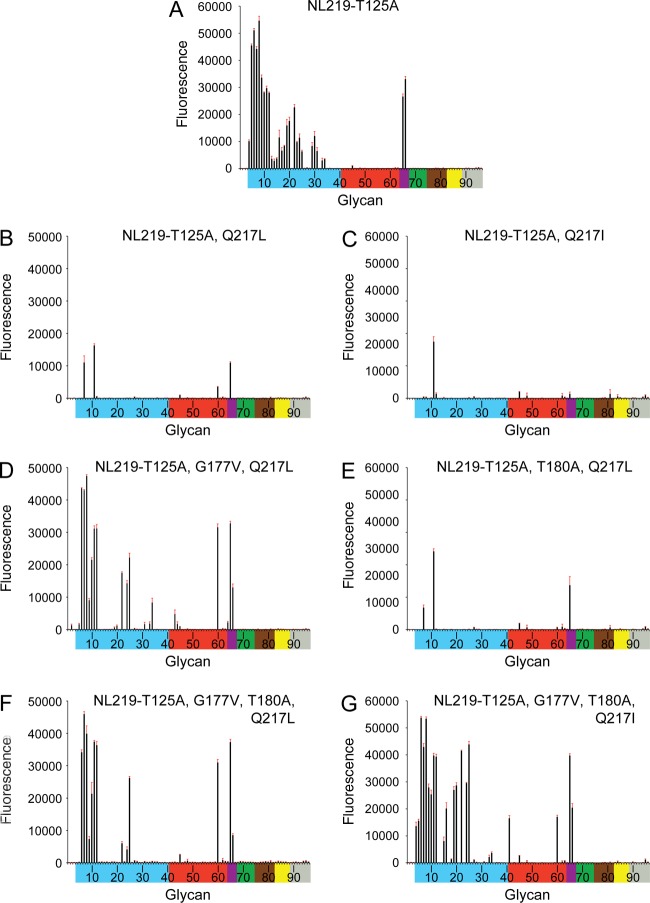

To probe the structural features of these recent H7 HAs in binding human receptors, a comparison of the HA RBS sequence of NL219 to SH-2 highlighted only 4 substitutions (Thr125Ala, Gly177Val, Thr180Ala, and Gln217Leu) in the RBS sequence (Fig. 5A and B). These four differences together with the Gln217Ile change seen in HGZ-1 were introduced in different combinations (Table 1) and assessed for receptor binding using glycan microarrays. In agreement with the previous study (28), results showed that loss of the glycosylation site (NL219-T125A) did reduce binding to avian α2-3-type receptors on the array (Fig. 6A and 3D). However, introduction of the Gln217Leu (NL219-T125A and Q217L; SH-2-like) and Gln217Ile (NL219-T125A and Q217I; HGZ-1-like) substitutions on the NL219-T125A framework both drastically reduced binding of avian receptors (Fig. 6B and 4C). While only one glycan, an α2-3 biantennary sialoside (glycan 11) bound to the NL219-T125A Q217I recHA, moderate binding was observed to a further two glycans, a fucosylated/sulfated sialoside (glycan 7), an α2-3/α2-6 branched sialoside (glycan 65), and the internal α2-6 LSTb glycan (glycan 60) for the NL219-T125A Q217L (SH-2-like) recHA. Introduction of a further Gly177Val (NL219-T125A, G177V, and Q217L) or a Thr180Ala (NL219-T125A, T180A, and Q217L) only produced an improvement in binding to the array with the Gly177Val substitution (Fig. 6D and 4E). The binding profile for this HA resembled that of SH-2 (Fig. 6B), with restricted α2-3 binding (glycans 6 to 8, 10 to 12, and 65 and 66) together with the α2-6 LSTb glycan (glycan 60). The last two combinations of mutations, the NL219-T125A, G177V, T180A, and Q217L combination and the NL219-T125A, G177V, T180A, and Q217I combination generated the SH-2 and HGZ-1 RBS on the NL219 framework. Similar to results with the wild-type proteins, NL219-T125A, G177V, T180A, and Q217L (Fig. 6F) and NL219-T125A, G177V, T180A, and Q217I (Fig. 6G) yielded signals for essentially the same glycans as SH-2 (Fig. 2B) and HGZ-1 (Fig. 2C), respectively.

Fig 5.

Receptor binding site differences between NL219 and SH-2. (A) The RBS residues of SH-1, SH-2, and HGZ-1 are compared to the RBS residues in NL219. Residues that are identical to those in NL219 are shown as periods. Gaps introduced to maximize alignment are indicated by dashes. (B) The four differences between NL219 and SH-2 are shown in red boxes on the SH-2 RBS structure with a Neu5Ac(α2-3)Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc (3SLN) glycan modeled into the RBS.

Fig 6.

Glycan microarray binding analysis of NL219 H7 RBS mutant recombinant HAs. To assess the effects of the RBS sequence differences between NL219 and SH-2 on receptor binding, mutations were introduced on the NL219 framework, and recombinant HAs were analyzed by glycan microarray. Glycans on the microarray are grouped and colored as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

Effect of Gly219Ser substitution on glycan binding.

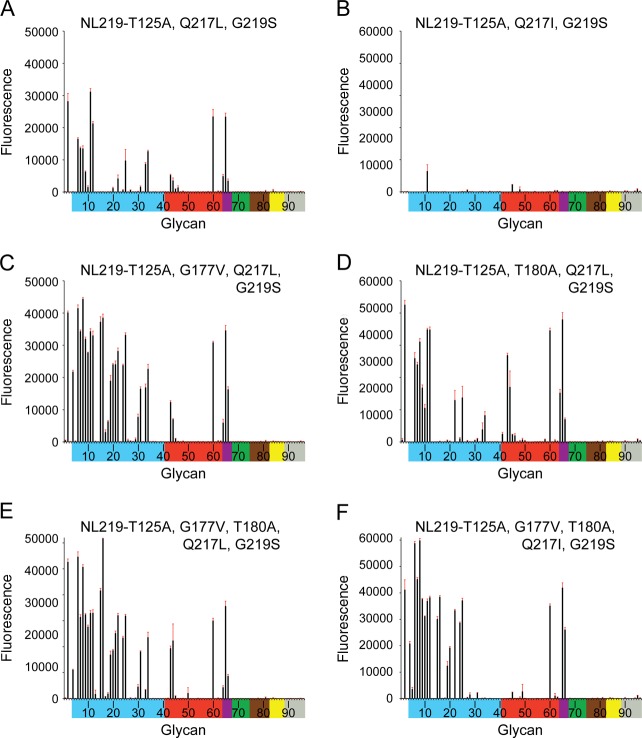

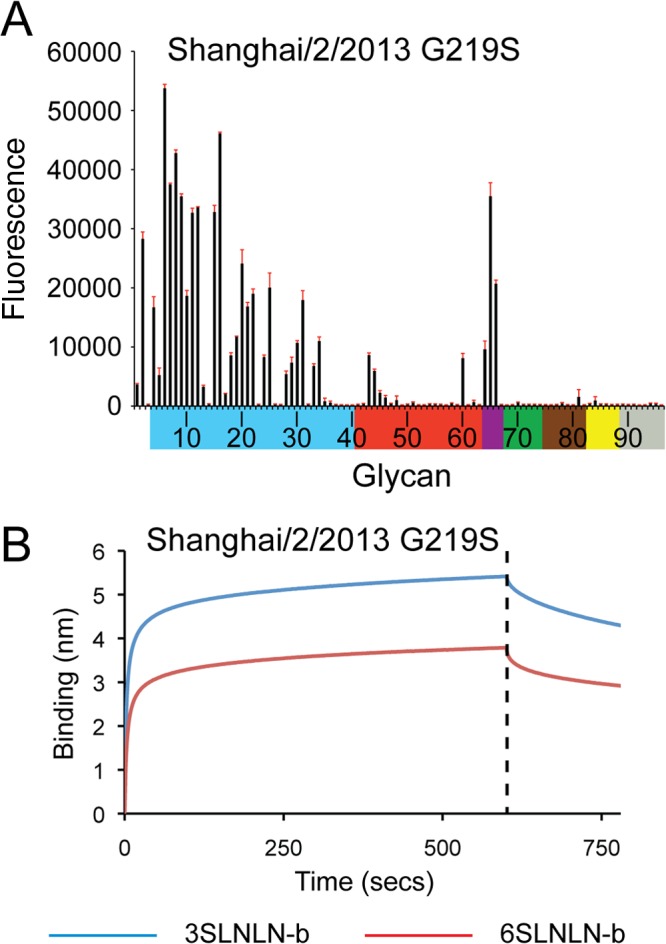

Knowing the Gln217Leu change to be equivalent to the Gln226Leu change seen in H2N2 and H3N2 adaptation to humans (25, 26), a Gly219Ser substitution (equivalent to Gly228Ser in H3 numbering) was also analyzed to assess whether these two combined changes on the SH-2 framework would produce a more significant switch to human receptor binding. A Gly219Ser substitution was introduced on the six mutation clones described in the previous section, and these were also subjected to glycan microarray analyses. Comparing the six NL219 mutations (Fig. 6B, C, D, E, F, and G) to their counterparts with the Gly219Ser substitution (Fig. 7A, B, C, D, E, and F) revealed a general overall increase in binding signals. However, there was no significant α2-3/α2-6 switch in receptor specificity. This was also reflected in SH-2 G219S recHA's binding to the glycan microarray as well as analysis by BLI (Fig. 8A and B and Table 6).

Fig 7.

Glycan microarray binding analysis of NL219 H7 RBS mutant recombinant HAs. To assess the effect of residue Gly219Ser substitution on the RBS, this substitution was introduced into each of the mutation clones shown in Fig. 6B to G, and their recombinant HAs were analyzed by glycan microarray. Glycans on the microarray are grouped and colored as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

Fig 8.

Glycan microarray binding and kinetic analysis of SH-2 G219S. (A and B) Glycan binding to recombinant HA was analyzed by glycan microarray (A) and BLI (B). Glycans on the microarray are grouped and colored as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

Table 6.

Kinetic results for glycan binding to SH-2 G219S recHA

| Glycan | Apparent KD (μM) | kon (ms−1) | kobs (mean ± SE) (×10−2 s−1) | koff (mean ± SE) (×10−2 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3SLNLN-b | 0.14 | 27,652 | 15.4 ± 0.27 | 0.38 ± 0.006 |

| 6SLNLN-b | 0.30 | 21,828 | 12.5 ± 0.20 | 0.64 ± 0.01 |

DISCUSSION

Subtype H7 influenza viruses continue to circulate globally, with more than 200 reports of human infections. As with H5N1, H7 viruses currently circulate as LPAI as well as HPAI viruses. In addition, H7 HA has also successfully combined with more than one neuraminidase (NA) subtype to infect humans, and this broad compatibility between H7 and multiple NA subtypes increases its pandemic potential. Past H7 human cases resulted in mainly a conjunctival tropism and only one death (14), suggesting its infection pattern to be different from other subtypes. However, the 2013 H7N9 outbreak with its high mortality rate were all respiratory cases, highlighting a different tropism. Despite almost 80 years of active influenza research, little is known about the exact molecular determinants required for efficient interspecies transmission and pathogenicity. HA is a critical molecule, being the major protein on the virus surface and responsible for viral attachment and entry. It is also the major antigenic determinant to which a host elicits an immune response and thus constitutes an important molecule for study and surveillance.

In this study, we have analyzed three RBS variants, all from fatal cases that occurred during the 2013 H7N9 outbreak in China. Two of these were analyzed from a structural perspective, and their overall structures were found to be similar to the structures of other avian H7 HAs (Fig. 1) and of group 2 HAs in general (28). While this article was being prepared for publication, a report describing 2013 H7N9 HA structures was published (54). Comparison of the published structure (PDB 4BSF) with structures reported here reveals highly similar structures, and all Cα atoms for the monomers superimpose with an RMSD of only 0.72 Å.

From previous work, NL219 complexes with avian receptor analogs revealed the role played by Gln217 (226 in H3 numbering) in providing additional hydrogen bonding to the galactose vicinal to the SA in the bound glycan (28). Similarly, SH-1 with Gln217 binds to avian receptors on the glycan microarray, although binding was weaker than results for NL219 binding (Fig. 2A and D). Interestingly, despite this weak binding to α2-6 glycans on the glycan microarray, Shanghai/1/13 recHA did show a significant binding response to 6SLNLN-b by BLI. Although this discrepancy may be due to the high observed off-rate, it is interesting to note that although Shanghai/1/13 HA has the avian 217Q, it also possesses a serine instead of an avian conserved alanine at position 128. A serine at this position was previously reported to confer increased binding to α2-6 SA in an Indonesian H5N1 swine isolate (55).

HGZ-1 with an Ile217 substitution yielded results similar to those for SH-1, but it also had weak binding signals to the α2-6 glycans on the array (Fig. 2C). This 217 substitution is of interest, as although it is not recognized as a residue for adaptation to humans, it has been the consensus residue at the equivalent position 226 for circulating A(H3N2) human influenza viruses since 2004. However, only 3 of the 21 human viruses from the 2013 outbreak with this HA region sequenced and deposited in the GISAID database (as of 21 June 2013) possessed Ile217. The bulk of the sequences (16 entries in the GISAID database) were the Leu217 variant.

Glycan microarray analysis of SH-2, a Leu217 variant, revealed a weaker avian α2-3 receptor preference compared to that of SH-1 and very weak binding to human α2-6 sialosides. The observed weak binding to human α2-6 receptors is in contrast to results with A(H7N9) viruses such as Anhui/1/2013, which has the same HA sequence as SH-2 and Hangzhou/1/2013 but showed more pronounced binding to α2-6 receptors (51, 52). Here, one needs to consider the increased valency of a virus with multiple HAs on its surface, which can show enhanced binding to weak-affinity ligands through increased avidity on the glycan microarray. While recHA is prepared for microarray analysis by forming complexes that yield a maximum of four trimers per complex, virions have approximately 400. Thus, recHA has lower avidity in these experiments, and only strong binders are usually visualized. This can complement virus experiments to help discriminate glycans that elicit weak and strong interactions.

It is also important to note that insect cells differ from mammalian cells in that they do not produce complex glycans (56). In addition, the closer a glycosylation site is to the RBS, the greater the potential of these glycan differences to affect receptor binding (57). Despite these differences, previously published results for glycan microarrays comparing recHA to virus binding demonstrate good agreement for high-affinity interactions (27, 28, 42). Thus, the weak binding to human α2-6 sialosides reported here is due to their weak interaction with the A(H7N9) RBS and is not a function of the assay. Indeed, this weak binding was also confirmed by kinetic analysis using BLI, a biosensor assay that detects real-time binding of the recombinant HA to biotinylated glycans (Fig. 4B).

Attempts were also made to probe the RBS to elucidate the residue changes that affect receptor binding. Of the changes introduced, the Thr125Ala and Gly177Val substitutions had the most pronounced effect on receptor binding. While T125Ala reduced overall glycan binding compared to NL219 (Fig. 2D and 4A), glycan binding to the Gln217Leu variants was recovered only when the Gly177Val substitution was introduced (Fig. 6D). Introduction of a hydrophobic residue may force a glycan to bind only in certain conformations, which may explain the restricted binding preference for sulfated and linear α2-3 sialosides. However, the reason for the improved binding cannot be explained from the structure alone, since comparison of the SH-1 (Gly177) and SH-2 (Val177) structures revealed little change in the surrounding region.

The only strong signals seen for binding to α2-6 sialosides were to the internal sialoside, LSTb, which suggests that this type of glycan has good affinity for this HA. The significance of this glycan is unknown, since LSTb has been found only in human milk (58). However, it was also a feature highlighted in a recent study with the A(H7N2) HA, NY107 for which an LSTb/complex structure was reported (31). The additional LSTb complexes reported here were consistent with the glycan microarray data. The SH-2/LSTb complex highlights the role of the 210-loop forming interactions with the branched Gal of LSTb, thus improving the binding preference for this particular glycan. With the weak observed signals for α2-6-linked SA, an additional Gly219Ser mutation (Gly228Ser in H3 numbering) was introduced to assess whether the double mutation would improve binding to α2-6 glycans. On the NL219 framework, there was an improvement in overall binding signals to both α2-3 and α2-6 glycans, which is consistent with recent reports (Fig. 7) (59, 60). However, there was no obvious switch in receptor specificity. When the same Gly219Ser mutation was incorporated onto the SH-2 framework, a similar result was observed (Fig. 8) (60).

Despite its weak binding to human receptor analogs, data presented here and elsewhere (52, 54, 59–61) agree that the virus HA has acquired an ability to bind some human α2-6 receptors that may have contributed to the recent outbreak and human infections in China. To date, there has been no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission in the human population, and thus, further changes in the RBS are required to initiate sustained human infection and transmission. It is unknown whether an HA with increased overall binding to glycans increases its pathogenicity. Further, it remains unknown what additional HA RBS changes are necessary to effect a switch to human receptor binding. Of critical importance is the continued surveillance of A(H7N9) influenza viruses as they circulate in avian populations and possibly other animal reservoirs to monitor any further changes that may adversely affect receptor specificity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Creation of the cDNA for this work was supported in part by BARDA contract HHSO100201000061C with Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics. Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Glycan microarray slides were produced under contract for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention using a glycan library generously provided by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) (www.functionalglycomics.org) funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM62116.

We thank the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) and in particular the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for depositing their A(H7N9) HA sequences to the GISAID database. We thank Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics for sharing the A(H7N9) HA genes that were used as the templates during cloning. We thank the staff of SER-CAT sector 22 for their help with data collection. We also thank the CFG for supplying glycans for direct binding experiments through their resource request program.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Thompson MG, Shay DK, Zhou H, Bridges CB, Cheng PY, Burns E, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. 2010. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza - United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59:1057–1062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, Shu B, Lindstrom S, Balish A, Sessions WM, Xu X, Skepner E, Deyde V, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Gubareva L, Barnes J, Smith CB, Emery SL, Hillman MJ, Rivailler P, Smagala J, de Graaf M, Burke DF, Fouchier RA, Pappas C, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Lopez-Gatell H, Olivera H, Lopez I, Myers CA, Faix D, Blair PJ, Yu C, Keene KM, Dotson PD, Jr, Boxrud D, Sambol AR, Abid SH, St. George K, Bannerman T, Moore AL, Stringer DJ, Blevins P, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Ginsberg M, Kriner P, Waterman S, Smole S, Guevara HF, Belongia EA, Clark PA, Beatrice ST, Donis R, Katz J, Finelli L, Bridges CB, Shaw M, Jernigan DB, Uyeki TM, Smith DJ, Klimov AI, Cox NJ. 2009. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 325:197–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawaoka Y, Bean WJ, Webster RG. 1989. Evolution of the hemagglutinin of equine H3 influenza viruses. Virology 169:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholtissek C, Rohde W, Von Hoyningen V, Rott R. 1978. On the origin of the human influenza virus subtypes H2N2 and H3N2. Virology 87:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown IH. 2010. Summary of avian influenza activity in Europe, Asia, and Africa, 2006-2009. Avian Dis. 54:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Bartelds AI, Wilbrink B, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. 2003. The 2002/2003 influenza season in the Netherlands and the vaccine composition for the 2003/2004 season. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 147:1971–1975 [In Dutch.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peiris M, Yuen KY, Leung CW, Chan KH, Ip PL, Lai RW, Orr WK, Shortridge KF. 1999. Human infection with influenza H9N2. Lancet 354:916–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, Perdue M, Swayne D, Bender C, Huang J, Hemphill M, Rowe T, Shaw M, Xu X, Fukuda K, Cox N. 1998. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science 279:393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster RG, Geraci J, Petursson G, Skirnisson K. 1981. Conjunctivitis in human beings caused by influenza A virus of seals. N. Engl. J. Med. 304:911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banks J, Speidel E, Alexander DJ. 1998. Characterisation of an avian influenza A virus isolated from a human–is an intermediate host necessary for the emergence of pandemic influenza viruses? Arch. Virol. 143:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004. Update: influenza activity–United States and worldwide, 2003-04 season, and composition of the 2004-05 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53:547–552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004. Update: influenza activity–United States, 2003-04 season. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53:284–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Editorial Team 2007. Avian influenza A/(H7N2) outbreak in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill. 12(22):pii=3206 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=3206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Schutten M, Van Doornum GJ, Koch G, Bosman A, Koopmans M, Osterhaus AD. 2004. Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:1356–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirst M, Astell CR, Griffith M, Coughlin SM, Moksa M, Zeng T, Smailus DE, Holt RA, Jones S, Marra MA, Petric M, Krajden M, Lawrence D, Mak A, Chow R, Skowronski DM, Tweed SA, Goh S, Brunham RC, Robinson J, Bowes V, Sojonky K, Byrne SK, Li Y, Kobasa D, Booth T, Paetzel M. 2004. Novel avian influenza H7N3 strain outbreak, British Columbia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2192–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M, Natrop G, van der Nat H, Vennema H, Meijer A, van Steenbergen J, Fouchier R, Osterhaus A, Bosman A. 2004. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza A virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in the Netherlands. Lancet 363:587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz J, Manvell RJ, Banks J. 1996. Avian influenza virus isolated from a woman with conjunctivitis. Lancet 348:901–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Nair P, Acheson P, Baker A, Barker M, Bracebridge S, Croft J, Ellis J, Gelletlie R, Gent N, Ibbotson S, Joseph C, Mahgoub H, Monk P, Reghitt TW, Sundkvist T, Sellwood C, Simpson J, Smith J, Watson JM, Zambon M, Lightfoot N. 2006. Outbreak of low pathogenicity H7N3 avian influenza in UK, including associated case of human conjunctivitis. Euro Surveill. 11(18):pii=2952 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puzelli S, Di Trani L, Fabiani C, Campitelli L, De Marco MA, Capua I, Aguilera JF, Zambon M, Donatelli I. 2005. Serological analysis of serum samples from humans exposed to avian H7 influenza viruses in Italy between 1999 and 2003. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tweed SA, Skowronski DM, David ST, Larder A, Petric M, Lees W, Li Y, Katz J, Krajden M, Tellier R, Halpert C, Hirst M, Astell C, Lawrence D, Mak A. 2004. Human illness from avian influenza H7N3, British Columbia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2196–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization 2013. Avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, Chen J, Jie Z, Qiu H, Xu K, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu W, Gao Z, Xiang N, Shen Y, He Z, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Zhao X, Zhou L, Li X, Zou S, Zhang Y, Yang L, Guo J, Dong J, Li Q, Dong L, Zhu Y, Bai T, Wang S, Hao P, Yang W, Han J, Yu H, Li D, Gao GF, Wu G, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Shu Y. 2013. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:1888–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, Chen Z, Li F, Wu H, Xiang N, Chen E, Tang F, Wang D, Meng L, Hong Z, Tu W, Cao Y, Li L, Ding F, Liu B, Wang M, Xie R, Gao R, Li X, Bai T, Zou S, He J, Hu J, Xu Y, Chai C, Wang S, Gao Y, Jin L, Zhang Y, Luo H, Yu H, Gao L, Pang X, Liu G, Shu Y, Yang W, Uyeki TM, Wang Y, Wu F, Feng Z. 24 April 2013. Preliminary report: Epidemiology of the avian influenza A (H7N9) outbreak in China. N. Engl. J. Med. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1056/NEJMoa1304617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matrosovich MN, Gambaryan AS, Teneberg S, Piskarev VE, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, Robertson JS, Karlsson KA. 1997. Avian influenza A viruses differ from human viruses by recognition of sialyloligosaccharides and gangliosides and by a higher conservation of the HA receptor-binding site. Virology 233:224–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers GN, Paulson JC, Daniels RS, Skehel JJ, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. 1983. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza hemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature 304:76–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor RJ, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG, Paulson JC. 1994. Receptor specificity in human, avian, and equine H2 and H3 influenza virus isolates. Virology 205:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang H, Carney P, Stevens J. 2010. Structure and receptor binding properties of a pandemic H1N1 virus hemagglutinin. PLoS Curr. 2:RRN1152. 10.1371/currents.RRN1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Carney PJ, Donis RO, Stevens J. 2012. Structure and receptor complexes of the hemagglutinin from a highly pathogenic H7N7 influenza virus. J. Virol. 86:8645–8652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank S, Kammerer RA, Mechling D, Schulthess T, Landwehr R, Bann J, Guo Y, Lustig A, Bachinger HP, Engel J. 2001. Stabilization of short collagen-like triple helices by protein engineering. J. Mol. Biol. 308:1081–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens J, Corper AL, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Wilson IA. 2004. Structure of the uncleaved human H1 hemagglutinin from the extinct 1918 influenza virus. Science 303:1866–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang H, Chen LM, Carney PJ, Donis RO, Stevens J. 2010. Structures of receptor complexes of a North American H7N2 influenza hemagglutinin with a loop deletion in the receptor binding site. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001081. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BD Biosciences. 1999. Baculovirus expression vector system manual, 6th ed. BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chayen NE, Shaw-Steward PD, Blow DM. 1992. Microbatch crystallization under oil – a new technique allowing many small volume crystallization experiments. J. Cryst. Growth 122:176–180 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otwinowski A, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, III, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2005. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61:458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emsley P, Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50:760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. 2001. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57:122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blixt O, Head S, Mondala T, Scanlan C, Huflejt ME, Alvarez R, Bryan MC, Fazio F, Calarese D, Stevens J, Razi N, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, van Die I, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Cummings R, Bovin N, Wong CH, Paulson JC. 2004. Printed covalent glycan array for ligand profiling of diverse glycan binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17033–17038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens J, Blixt O, Chen LM, Donis RO, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2008. Recent avian H5N1 viruses exhibit increased propensity for acquiring human receptor specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 381:1382–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens J, Blixt O, Glaser L, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Glycan microarray analysis of the hemagglutinins from modern and pandemic influenza viruses reveals different receptor specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 355:1143–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevens J, Blixt O, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2003. X-ray structure of the hemagglutinin of a potential H3 avian progenitor of the 1968 Hong Kong pandemic influenza virus. Virology 309:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2001. X-ray structures of H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus hemagglutinins bound to avian and human receptor analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:11181–11186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Stevens DJ, Haire LF, Walker PA, Coombs PJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2009. Structures of receptor complexes formed by hemagglutinins from the Asian influenza pandemic of 1957. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17175–17180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Skehel JJ. 2004. H1 and H7 influenza haemagglutinin structures extend a structural classification of haemagglutinin subtypes. Virology 325:287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell RJ, Kerry PS, Stevens DJ, Steinhauer DA, Martin SR, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2008. Structure of influenza hemagglutinin in complex with an inhibitor of membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:17736–17741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature 289:366–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 10 July 2013. Pathogenesis and transmission of A (H7N9) avian influenza virus in ferrets and mice. Nature [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1038/nature12391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe T, Kiso M, Fukuyama S, Nakajima N, Imai M, Yamada S, Murakami S, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Sakoda Y, Takashita E, McBride R, Noda T, Hatta M, Imai H, Zhao D, Kishida N, Shirakura M, de Vries RP, Shichinohe S, Okamatsu M, Tamura T, Tomita Y, Fujimoto N, Goto K, Katsura H, Kawakami E, Ishikawa I, Watanabe S, Ito M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Sugita Y, Uraki R, Yamaji R, Eisfeld AJ, Zhong G, Fan S, Ping J, Maher EA, Hanson A, Uchida Y, Saito T, Ozawa M, Neumann G, Kida H, Odagiri T, Paulson JC, Hasegawa H, Tashiro M, Kawaoka Y. 10 July 2013. Characterization of H7N9 influenza A viruses isolated from humans. Nature [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1038/nature12392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belser JA, Blixt O, Chen L-M, Pappas C, Maines TR, Van Hoeven N, Donis RO, Busch J, McBride R, Paulson JC, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2008. Contemporary North American influenza H7 viruses possess human receptor specificity: implications for virus transmissibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7558–7563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong X, Martin SR, Haire LF, Wharton SA, Daniels RS, Bennett MS, McCauley JW, Collins PJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Gamblin SJ. 2013. Receptor binding by an H7N9 influenza virus from humans. Nature 499:496–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nidom CA, Takano R, Yamada S, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Daulay S, Aswadi D, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Shinya K, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Muramoto Y, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Influenza A (H5N1) viruses from pigs, Indonesia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1515–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kost TA, Condreay JP, Jarvis DL. 2005. Baculovirus as versatile vectors for protein expression in insect and mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 23:567–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang CC, Chen JR, Tseng YC, Hsu CH, Hung YF, Chen SW, Chen CM, Khoo KH, Cheng TJ, Cheng YS, Jan JT, Wu CY, Ma C, Wong CH. 2009. Glycans on influenza hemagglutinin affect receptor binding and immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:18137–18142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weinstein J, de Souza-e-Silva U, Paulson JC. 1982. Sialylation of glycoprotein oligosaccharides N-linked to asparagine. Enzymatic characterization of a Galβ1→3(4)GlcNAc α2→3 sialyltransferase and a Galβ1→4GlcNAc α2→6 sialyltransferase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 257:13845–13853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Srinivasan K, Raman R, Jayaraman A, Viswanathan K, Sasisekharan R. 2013. Quantitative description of glycan-receptor binding of influenza A virus H7 hemagglutinin. PLoS One 8:e49597. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tharakaraman K, Jayaraman A, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Stebbins NW, Johnson D, Shriver Z, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 20 June 2013. Glycan receptor binding of the influenza A virus H7N9 hemagglutinin. Cell [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou J, Wang D, Gao R, Zhao B, Song J, Qi X, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Yang L, Zhu W, Bai T, Qin K, Lan Y, Zou S, Guo J, Dong J, Dong L, Wei H, Li X, Lu J, Liu L, Zhao X, Huang W, Wen L, Bo H, Xin L, Chen Y, Xu C, Pei Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, Wang S, Feng Z, Han J, Yang W, Gao GF, Wu G, Li D, Wang Y, Shu Y. 2013. Biological features of novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nature 499:500–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delano WL. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA: http://www.pymol.org [Google Scholar]