Abstract

Background

There is a growing body of literature indicating that attitudes toward aging significantly affect older adults’ psychological well-being. However, there is a paucity of scientific investigations examining the role of older adults’ attitudes toward aging on their spouses’ psychological well-being. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the dyadic effects of attitude toward aging on the psychological well-being of older couples.

Methods

Data for the present study, consisting of 300 couples aged 50 years and older, were drawn from a community-based survey entitled “Poverty among Elderly Women: Case Study of Amanah Ikhtiar” conducted in Peninsular Malaysia. An actor–partner interdependence model using AMOS version 20 (Europress Software, Cheshire, UK) was used to analyze the dyadic data.

Results

The mean ages of the husbands and wives in this sample were 60.37 years (±6.55) and 56.33 years (±5.32), respectively. Interdependence analyses revealed significant association between older adults’ attitudes toward aging and the attitudes of their spouses (intraclass correlation =0.59; P<0.001), and similar interdependence was found for psychological well-being (intraclass correlation =0.57; P<0.001). The findings from AMOS revealed that the proposed model fits the data (CMIN/degrees of freedom =3.23; goodness-of-fit index =0.90; confirmatory fit index =0.91; root mean square error of approximation =0.08). Results of the actor–partner independence model indicated that older adults’ psychological well-being is significantly predicted by their spouses’ attitudes toward aging, both among older men (critical ratio =2.92; P<0.01) and women (critical ratio =2.70; P<0.01). Husbands’ and wives’ own reports of their attitudes toward aging were significantly correlated with their own and their spouses’ psychological well-being.

Conclusion

The findings from this study supported the proposed Spousal Attitude–Well-Being Model, where older adults’ attitudes toward aging significantly affected their own and their spouses’ psychological well-being. The theoretical and practical implications of the findings are discussed.

Keywords: aged, attitude toward aging, psychological well-being

Introduction

As the population ages, interest in maintaining and improving older adults’ psychological well-being as an important indicator of quality of life, has received substantial scholarly attention in gerontological research. In light of this consideration, several scientific investigations have been conducted to find the biopsychosocial factors affecting psychological well-being in later life.1,2

In recent years, the role of attitudes toward one’s own aging as a psychosocial determinant of older adults’ health has been studied.3 Attitudes toward one’s own process of aging, as a modifiable factor,4 refers to expectations about the personal experience of aging. In other words, the personal experience of aging refers to the way that individuals perceive their own aging.5 There is a growing body of literature that indicates that attitudes toward aging significantly affect older adults’ psychological well-being.6,7 For example, Levy et al4 conducted a longitudinal study from 1977 to 1995 to investigate the impact of self-perceptions of aging on functional health over time. The authors found that more positive attitudes toward aging were significantly associated with better functional health, after controlling for baseline measures of functional health and several sociodemographic factors. The Ohio Longitudinal Study of Aging and Retirement (OLSAR)8 also showed that beliefs about aging predict cause-specific mortality. The OLSAR found that a positive attitude toward aging was significantly related to lower mortality rates among patients with respiratory problems. Similarly, the results of a cross-sectional study conducted on a sample of 405 older adults at six elderly welfare centers in a metropolitan city in South Korea showed that attitudes about aging were significant factors for enhancing life satisfaction.9 Conversely, the findings from a random sample of 316 community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan showed that negative attitudes toward aging contributed to depressive symptoms.10 Overall, the existing research shows that self-perceptions of aging are independently correlated with physical and psychological health,11 life-satisfaction,12 and depression.13 Although existing evidence shows physical and psychological benefits of positive attitudes toward one’s own aging among older adults, it is worth mentioning that the role of attitudes toward aging on psychological well-being should also be investigated from the dyadic perspective because husbands and wives are interdependent and affect each other. Kenny et al14 stated that people involved in dyadic relationships may influence each other’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the extent to which attitudes toward aging among older adults and their spouses may exhibit reciprocal benefits. Therefore, the main aim of the present study is to examine the dyadic effects of attitudes toward aging on the psychological well-being of older couples in Malaysia.

Theoretical model

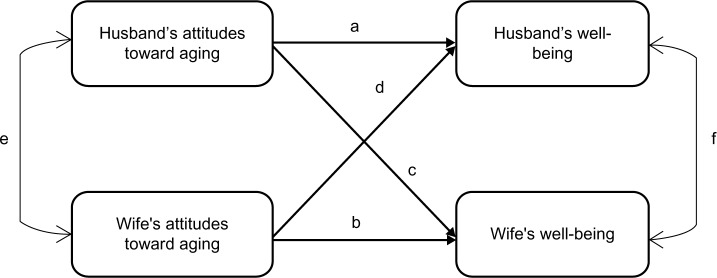

In order to examine the potential dyadic effects of attitudes toward aging on the psychological well-being of older couples, we developed a theoretical model called the “Spousal Attitude–Well-Being Interdependence Model” (Figure 1). According to family system theory, a family is viewed as an interdependent system, whereby each member reciprocally influences and is influenced by other family members’ thoughts, feelings, and actions. In other words, family members’ emotions, cognition, and behaviors affect other family members’ emotions, cognition, and behaviors.15 Therefore, each family member has a psychological and emotional influence on other family members. According to the proposed model, the actor effect is explained in terms of how one’s attitude toward the aging of older adults and their spouses influences one’s own well-being. The partner effect is explained in terms of how older adults’ attitudes toward aging influence the well-being of their spouses, and vice versa. In addition, nonindependence is explained in terms of how older adults’ well-being is similar to spouses’ well-being, and how older adults’ attitudes toward aging are similar to their spouses’ attitudes toward aging.

Figure 1.

Spousal Attitude–Well-Being Model.

Notes: Arrows “a” and “b” reflect actor effects, arrows “c” and “d” reflect partner effects, and arrows “e” and “f” indicate interdependence.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the arrows “a” and “b” demonstrate actor effects; wherein the husband’s attitude toward aging influences his well-being, and the wife’s attitude toward aging influences her well-being. Partner effects have been proposed by the arrows “c” and “d”, where the husband’s attitude toward aging influences the well-being of his wife, and the wife’s attitude toward aging influences her husband’s well-being. The arrow “e” proposes an association between older adults and their spouses in terms of their attitudes toward aging. Finally, arrow “f ” suggests an association between the husband’s well-being and the wife’s well-being. According to the proposed model, which is in line with a previous study which mentioned that attitudes toward aging are significantly associated with the health and well-being of older adults,3,16,17 it is hypothesized that older adults’ attitudes toward aging significantly contribute to their own psychological well-being. In addition, in accordance with previous studies showing interspousal associations between well-being and health status,18–20 this model will test the interdependence effects of attitudes toward aging and psychological well-being between spouses. The most important goal of this model is to test the partner effects of attitudes toward aging on the psychological well-being of older adults and their partners.

Methods

The study population, consisting of 300 couples aged 50 years and older, was drawn from a community-based survey entitled “Poverty among Elderly Women: Case Study of Amanah Ikhtiar” conducted in 2011. The survey utilized a multistage stratified sampling technique to select couples from Peninsular Malaysia (west Malaysia). The response rate was 100%. All selected couples were interviewed face-to-face by trained interviewers. The trainings for the enumerators were carried out by research teams. The research team went through each question and asked the enumerators to practice recording possible answers. Completed questionnaires were checked by members of the research team to ensure complete responses to the questions. In certain cases, verification of the information provided by the respondents was carried out through telephone.

Instruments

Attitude toward aging

Attitudes toward aging were measured using a four-item scale developed and validated by the authors. The items included: 1) older adults are respected for their knowledge and wisdom; 2) I will have more time with family and friends when I grow old; 3) I hope to be able to do what I want when I grow old; and 4) old age is time for resting. Each item was rated on a three-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1–3. The internal consistency for attitude toward aging (using Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.80 for women and 0.82 for older men. The findings from the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed construct validity for both groups. The results among women revealed that the four items had factor loadings of more than 0.6, and that collectively, all four items explained 62.6% of the variance in attitudes toward aging (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin =0.78; eigenvalue =2.5). Among older men, the results from the EFA also revealed one factor with an eigenvalue of 2.6 (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin =0.77); 64.9% of the total factor variance was explained by four items.

Psychological well-being

The World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) was used to measure psychological well-being. The WHO-5 consisted of five positively worded items including “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits”; “I have felt calm and relaxed”; “I have felt active and vigorous”; “I woke up feeling fresh and rested”; and “My daily life has been filled with things that interest me.” The theoretical raw score ranges from 0 to 25, and is transformed into a scale with scores ranging from 0 to 100; higher scores suggest higher levels of psychological well-being.21,22 The scale has received good reliability and validity among older Malaysians.23,24 In the present study, The WHO-5 showed strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 for the female respondents, and 0.90 for the males. The EFA established the unidimensionality of the scale, where the first factor with an eigenvalue of 3.46 explained 69% of the total variance for females. Unidimensionality of the scale was also established for males, where the first factor with an eigenvalue of 3.5 accounted for 70.3% of the total factor variance.

Analytic strategies

First, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency reliability were applied to evaluate the psychometric properties of the scales used in the study. Next, descriptive statistics (for example, mean, standard deviation, and frequency) were performed to provide a profile of the general characteristics of the sample. Finally, the actor– partner interdependence model (APIM) using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA)/AMOS version 20 (Europress Software, Cheshire, UK) was used to perform dyadic analysis. The APIM as a new statistical modeling technique, was proposed by a number of authors,14,25–27 to explore how individuals’ independent variables simultaneously and independently contribute to their own dependent variables and to their partners’ dependent variables. This statistical approach is commonly used to study pairs of individuals nested within family systems, such as couples, siblings, and in parent–child relationships, allowing researchers to better understand intra- and interpersonal effects simultaneously.14,26 The model allows researchers to study the impact of a individual factor on his or her own outcome variable (actor effect), as well as on the outcome variable of the partner (partner effect).28

The APIM can be categorized into four types of sub-models, including the actor-only pattern, the partner-only pattern, the couple pattern, and the social comparison pattern. The actor-only pattern indicates that individuals’ outcomes are influenced only by their own characteristics, and that the partner does not have any effect on the outcome. The partner-only pattern suggests that individual’s factors do not affect their own outcomes. In other words, an individual’s outcome is influenced by his or her partner’s characteristics. The next pattern, which was adopted for the current study, is the couple pattern. This pattern suggests that the individual is as affected by his/her own characteristics as well as by his/her spouse’s characteristics. Another pattern that is slightly similar to the couple pattern is the social-comparison pattern. The most important difference between the couple pattern and the social-comparison pattern is that the actor effect in the social-comparison pattern is a positive predictor of a person’s own outcomes, but his or her partner’s effect is a negative predictor of the spouse’s outcomes.29

In the present study (couple pattern), the actor effect is the outcome obtained from the husbands’/wives’ attitudes toward aging on their own psychological well-being. The partner effect is that a husband’s/wife’s attitudes toward aging affects the spouse’s psychological well-being. The following indices were used to assess the adequacy of the model fit: the goodness-of-fit index (GFI); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); the comparative fit index (CFI); the standardized root square mean residual; and the Tucker–Lewis index. According to Hu and Bentler,30 values of 0.06 and below for the RMSEA and the standard-ized root square mean residual, values greater than or equal to 0.90 for the GFI, and values greater than or equal to 0.95 for the CFI and the Tucker–Lewis index indicate model fit. Lastly, interdependence within spousal dyads on attitudes toward aging and psychological well-being were tested using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).31

Results

The mean ages of the husbands and wives in this sample were 60.37 years (±6.55 years) and 56.33 years (±5.32 years), respectively. The mean age difference between the spouses in this sample was 4.03 years (±4.66 years), and men were, on average, older than their wives. The majority of the couples were living in traditional houses (82%). Regarding educational attainment, 11.7% of women and 12.3% of their spouses had no formal education. In terms of educational homogamy, 64% of couples had the same level of education (6.3% no formal education; 31% primary education; and 26.7% secondary education). The mean score for attitudes toward aging was 9.53 (±1.64), with a possible range of 5–12. The mean psychological well-being score among this sample was 60.49 (±23.32). Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics for the sample according to sex.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the sample

| Variable | Husbands (n =300)

|

Wives (n=300)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | M | SD | n | % | M | SD | |

| Age | 60.37 | 6.54 | 56.33 | 5.32 | ||||

| No formal education | 37 | 12.3 | 35 | 11.7 | ||||

| Primary school | 142 | 47.3 | 143 | 47.7 | ||||

| Secondary | 121 | 40.3 | 122 | 40.7 | ||||

| Psychological well-being | 58.87 | 23.95 | 62.12 | 22.60 | ||||

| Attitude toward aging | 9.58 | 1.66 | 9.49 | 1.63 | ||||

Abbreviations: n, number; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

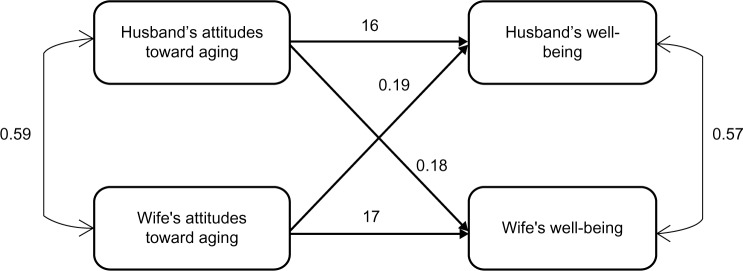

Actor effects

Actor effects were examined, while controlling for partner effects.14 The findings from AMOS that were used to determine the presence of actor effects revealed an acceptable model fit (CMIN/degrees of freedom [df] =2.23; GFI =0.91; CFI =0.95; RMSEA =0.06). Significant actor effects emerged between attitude toward aging and psychological well-being for both wives (critical ratio [CR] =2.68; P<0.01) and husbands (CR =2.61; P<0.01). As expected, the results that emerged when testing for actor effects revealed that attitudes toward aging significantly contributed to the psychological well-being of older men and women. Figure 2 illustrates the results of the APIM with standardized parameter estimates.

Figure 2.

Standardized parameter estimates.

Partner effects

The findings from AMOS revealed that the proposed model acceptably fits the data (CMIN/df =2.42; GFI =0.92; CFI =0.94; RMSEA =0.07). Results of the APIM indicated that older adults’ psychological well-being is significantly predicted by their spouses’ attitudes toward aging, among both older men (CR =2.75; P<0.01) and women (CR =2.70; P<0.01). Husbands’ attitudes toward aging significantly and positively predicted their wives’ well-being, while the wives’ attitudes toward aging significantly and positively predicted their husbands’ well-being (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of APIM results

| APIM parameters | Regression weights

|

CR | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized | SE | Standardized | |||

| Actor effect | |||||

| Wives | 0.407 | 0.152 | 0.173 | 2.68 | P<0.01 |

| Husbands | 0.401 | 0.154 | 0.165 | 2.61 | P<0.01 |

| Partner effect | |||||

| Husbands to wives | 0.485 | 0.176 | 0.189 | 2.75 | P<0.01 |

| Wives to husbands | 0.424 | 0.157 | 0.176 | 2.70 | P<0.01 |

Abbreviations: APIM, actor–partner interdependence model; SE, standard error; CR, critical ratio.

Interdependence effects

The results revealed a significant relationship between older adults’ attitude toward aging and the attitudes of their spouses (ICC =0.59; P<0.001), and a similar level of interdependence was noted for psychological well-being (ICC =0.57; P<0.001). In other words, with respect to attitudes toward aging and psychological well-being, people tended to be more like their dyad partners than to the average person in the sample as a whole.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to examine the dyadic effects of attitudes toward aging on spouses’ psychological well-being. Actor effects were tested while controlling for partner effects. As expected, attitudes toward aging had positive and statistically significant actor effects on psychological well-being for both husbands and wives. Consistent with the results from past studies, which indicated that attitudes toward aging affect subjective well-being and life satisfaction among older adults,3,4,7,10,32,33 our study showed a positive association between attitudes toward aging and psychological well-being among older couples. Attitudes toward aging appear to affect the psychological well-being of older adults through three mechanisms, including psychological, behavioral, and physiological pathways. The psychological pathway, where attitudes toward aging may negatively affect older adults’ well-being, is self-fulfilling prophecy (SFP). The SFP is an initially false belief of a situation that may lead to a new behavior, which then renders the originally false conception as true.34 This suggests that peoples’ attitudes toward aging might affect their own aging process in a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. Positive attitudes about aging may be internalized, with resultant positive expectations and, in turn, positive self-perceptions.17,35 Older adults with positive attitudes toward aging may assume that health problems are not a direct consequence of growing old, and that healthy practices are effective; therefore, they are willing to seek treatment and healthy practices as a result. It is found that a negative attitude towards aging heightens cardiovascular response to stress. Repeated elevations of cardiovascular response to stress increases susceptibility to cardiovascular events and consequently contributes to general low well-being.35

The partner effects of attitudes toward aging on the psychological well-being of older adults and their partners using the APIM model found that there were significant partner effects of attitude toward aging on their partners’ psychological well-being. This finding contributed new knowledge about the impact of attitudes toward aging on psychological well-being among older adults and their partners. This finding was slightly similar to the findings obtained from a study conducted by Kim et al36 on a sample of 168 married survivor–caregiver dyads. The researchers found that when a couple was dealing with a major illness, the extent to which women psychologically adjusted to the situation played a key role not only in their own well-being, but also in their spouse’s well-being.36 It was concluded that positive attitudes toward aging would benefit both partners. Our results are also consistent with Kashy and Kenny’s25 findings. They found that one’s psychological adjustment to a stressor was affected both by one’s own perceptions and by the partner’s perceptions. Similarly, the findings from a study conducted by Berg and Wilson37 on a sample of 104 infertile couples showed that one’s well-being could be affected not only by his/her own perceptions, but also by the partner’s perceptions.

The results of the interdependence analysis revealed a significant association between older adults’ attitudes toward aging and the attitudes of their spouses; there was a similar level of interdependence for psychological well-being as well. These findings expand upon those of previous studies, in which researchers found evidence for interdependence within elderly spousal dyads in measures of well-being18,20 and depressive symptoms.38,39 For example, Bookwala and Schulz18 investigated 1,040 elderly married couples and found that indicators of well-being for one spouse, such as perceived health, depressive symptoms, feelings about life as a whole, and satisfaction with life were significantly correlated with the well-being of the other spouse. Similarly, the results of a sample of 2,235 spousal dyads showed that individuals’ perceptions of well-being tend to be similar to those of their spouses.20 Tower and Kasl,40 in their study on a sample of 317 community-dwelling older couples, found that depressive symptoms in one spouse had a significant impact on depressive symptoms in the other spouse. Ko and Lewis41 also found that partners’ scores on depressive symptomatology were significantly correlated. These findings are consistent with the tenets of family system theory, where each family member has a psychological and emotional influence on other family members; in addition, these elements reciprocally influence and are influenced by other family members’ thoughts, feelings, and actions.15 According to Lewis et al42 and Wilson,43 the interrelated psychological well-being of older spouses may come from several paths. First, people tend to marry people who are similar in health, healthy behaviors, and health determinants (such as socioeconomic factors). Second, couples reside in common environments due to shared living. Third, couples engage in certain similar habits and behaviors that reduce their odds of developing health problems. In addition, the interdependence of spouses’ psychological well-being may be influenced by the events experienced by the couple as a unit.44

Limitations of the study

Although the APIM approach guiding this research is a notable strength of this investigation, the findings should be considered in view of some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes causality difficult to establish. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to better explore the causal direction of the effects observed in this study. The second limitation that should be addressed in future research is the effect of exogenous and confounding variables, which may affect the model.

Conclusion

Collectively, the results of the present study offer new insights into the effects of attitude toward aging and psychological well-being in later life. Attitudes toward aging appear to predict not only an individual’s own psychological well-being, but also that of his or her spouse. Therefore, spouses should be aware that their perceptions of aging affect their partners’ psychological well-being. The proposed model, which hypothesized that an older adult’s perception of his or her own aging significantly affected his or her own, and his or her spouse’s, psychological well-being was supported. It will be valuable to extend and test the generalizability of the proposed model of the “Spousal Attitude–Well-being Model” to a broader range of older couples. Future research should also continue to study the dyadic effects of other factors that may affect psychological well-being in later life.

Despite the limitations of this investigation, the current study has implications for research and practice. The findings highlight the importance of considering both intrapersonal and interpersonal factors that may influence older adults’ psychological well-being. In addition, programs for older adults and their spouses should be developed in order to enhance positive attitudes toward aging; this may facilitate successful adaptation in old age, and maximize an older adult’s psychological well-being.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Momtaz YA, Hamid TA, Yahaya N, Ibrahim R. Effects of chronic comorbidity on psychological well-being among older persons in northern peninsular Malaysia. Appl Res Qual Life. 2010;5(2):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abolfathi Momtaz Y, Hamid TA, Ibrahim R, Yahaya N, Abdullah SS. Moderating effect of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between chronic medical conditions and psychological well-being among elderly Malays. Psychogeriatrics. 2012;12(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai DW. Older Chinese’ attitudes toward aging and the relationship to mental health: an international comparison. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(3):243–259. doi: 10.1080/00981380802591957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy BR, Slade MD, Kasl SV. Longitudinal benefit of positive self-perceptions of aging on functional health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(5):P409–P417. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang Y, Poon LW, Kim SY, Shin BK. Self-perception of aging and health among older adults in Korea. J Aging Stud. 2004;18(4):485–496. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tess TM. Attitudes toward aging and their effects on behavior. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. 6th ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 379–406. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai DWL. Effect of social exclusion on attitude toward ageing in older adults living alone in Shanghai. Asian Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2012;7(2):88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy BR, Myers LM. Relationship between respiratory mortality and self-perceptions of aging. Psychology and Health. 2005;20(5):553–564. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh S, Choi H, Lee C, Cha M, Jo I. Association between knowledge and attitude about aging and life satisfaction among older Koreans. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2012;6(3):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu L, Kao SF, Hsieh YH. Positive attitudes toward older people and well-being among Chinese community older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2010;29(5):622–639. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker M, O’Hanlon A, McGee HM, Hickey A, Conroy RM. Cross-sectional validation of the Aging Perceptions Questionnaire: a multidimensional instrument for assessing self-perceptions of aging. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efklides A, Kalaitzidou M, Chankin G. Subjective quality of life in old age in Greece: the effect of demographic factors, emotional state and adaptation to aging. Eur Psychol. 8(3):178–191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyene Y, Becker G, Mayen N. Perception of aging and sense of well-being among Latino elderly. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2002;17(2):155–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1015886816483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis (Methodology in the Social Sciences) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broderick CB. Understanding Family Process: Basics of Family Systems Theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy BR. Mind matters: cognitive and physical effects of aging self-stereotypes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(4):P203–P211. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.p203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(2):261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bookwala J, Schulz R. Spousal similarity in subjective well-being: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Psychol Aging. 1996;11(4):582–590. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Windsor TD. Persistence in goal striving and positive reappraisal as psychosocial resources for ageing well: a dyadic analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(6):874–884. doi: 10.1080/13607860902918199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windsor TD, Ryan LH, Smith J. Individual well-being in middle and older adulthood: do spousal beliefs matter? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(5):586–596. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awata S, Bech P, Koizumi Y, et al. Validity and utility of the Japanese version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index in the context of detecting suicidal ideation in elderly community residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(1):77–88. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bech P. Measuring the dimension of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. Quality of Life Newsletter. 2004;32:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Momtaz YA, Hamid TA, Yahaya N. The role of religiosity on relationship between chronic health problems and psychological well-being among Malay Muslim older persons. Research Journal of Medical Sciences. 2009;3(6):188–193. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Momtaz YA, Ibrahim R, Hamid TA, Yahaya N. Mediating effects of social and personal religiosity on the psychological well being of widowed elderly people. Omega (Westport) 2010;61(2):145–162. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.2.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenny DA, Ledermann T. Detecting, measuring, and testing dyadic patterns in the actor-partner interdependence model. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(3):359–366. doi: 10.1037/a0019651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor-partner interdependence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int J Behav Dev. 2005;29(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledermann T, Macho S, Kenny DA. Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor-partner interdependence model. Struct Equ Modeling. 2011;18(4):595–612. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen LH, Li TS. Role balance and marital satisfaction in Taiwanese couples: an actor-partner independence model approach. Soc Indic Res. 2012;107(1):187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SS, Reed PG, Hayward RD, Kang Y, Koenig HG. Spirituality and psychological well-being: testing a theory of family interdependence among family caregivers and their elders. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(2):103–115. doi: 10.1002/nur.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kavirajan H, Vahia IV, Thompson WK, Depp C, Allison M, Jeste DV. Attitude Toward Own Aging and Mental Health in Post-menopausal Women. Asian J Psychiatr. 2011;4(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryant C, Bei B, Gilson K, Komiti A, Jackson H, Judd F. The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental health in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(10):1674–1683. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biggs M. Self-fulfilling prophecies. In: Bearman P, Hedstrom, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy B. Stereotype Embodiment: A Psychosocial Approach to Aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(6):332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):230–238. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg BJ, Wilson JF. Patterns of psychological distress in infertile couples. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;16(2):65–78. doi: 10.3109/01674829509042781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kouros CD, Cummings EM. Longitudinal Associations Between Husbands’ and Wives’ Depressive Symptoms. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(1):135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Townsend AL, Miller B, Guo S. Depressive symptomatology in middle-aged and older married couples: a dyadic analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(6):S352–S364. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tower RB, Kasl SV. Depressive symptoms across older spouses and the moderating effect of marital closeness. Psychol Aging. 1995;10(4):625–638. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ko LK, Lewis MA. The Role of Giving and Receiving Emotional Support on Depressive Symptomatology among Older Couples: An Application of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J Soc Pers Relat. 2011;28(1):83–99. doi: 10.1177/0265407510387888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson SE. The health capital of families: an investigation of the inter-spousal correlation in health status. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(7):1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brenes-Camacho G. Couples’ characteristics and the correlation of husbands’ and wives’ health; Paper presented at: Population Association of America 2013 Annual Meeting; April 11–13, 2013; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]