Abstract

Objective:

Neuroprotective, antioxidant, anticonvulsant, and analgesic effects of Nigella sativa (NS) have been previously shown. The interaction of NS with opioid system has also been reported. In the present study, the effects of NS hydro-alcoholic extract on the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) in rats were evaluated.

Materials and Methods:

CPP was induced by injection of morphine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) on three consecutive days in compartment A of the CPP apparatus. Injection of NS extract (200 and 400 mg/kg, i.p.) 60 min before morphine administration on the conditioning days and 60 min before the post-conditioning phase was done for the evaluation of acquisition and expression effects, respectively. Conditioning effect of NS extract was also evaluated by injection of extract (200 or 400 mg/kg, i.p.) in the conditioning phase, instead of morphine in different groups. The difference in time which the animals spent in compartment A on the day before conditioning and the days after conditioning was determined and compared between groups.

Results:

The time spent by the rats in compartment A in the morphine group was greater than that in the saline group (P < 0.01). Both doses of NS extract decreased acquisition of morphine-induced CPP (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001), but had no significant effect on the expression of morphine CPP. Higher dose of the extract (400 mg) showed a significant conditioning effect which was comparable to the effect of morphine.

Conclusion:

The results of the present study showed that the hydro-alcoholic extract of NS has conditioning effect. It also decreased acquisition, but had no significant effect on the expression of morphine CPP.

KEY WORDS: Conditioned place preference, morphine, Nigella sativa, rat

INTRODUCTION

In the general population, the prevalence of addiction varies from 3 to 16%.[1] Opiate abuse causes long-lasting neural changes in the brain that lead to several behavioral abnormalities associated with cognitive deficits, tolerance, and dependence.[2]

Addiction is a chronic disorder that requires long-term treatment. Medications including psychosocial interventions have frequently been used to prevent relapse. These medications generally reduce drug craving and the likelihood of relapse to compulsive drug use. Nevertheless, most of these treatment methods have given unsatisfactory results until now.[1]

Conditioned place preference (CPP) is a well-known method for evaluating the effects of drugs or natural products on morphine dependence.[3,4] In fact, in this method, the effects of the drugs on the rewarding properties of morphine are evaluated.[3,4]

The dopaminergic mesolimbic system that consists of ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens, and medial prefrontal cortex is considered to be crucial in the rewarding actions of opiates.[5,6] According to the results of previous studies, several neurotransmitter systems including dopamine, glutamate, acetylcholine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), histamine, and nitric oxide (NO) have been implicated in the rewarding properties of morphine.[7–15]

Nigella sativa L. (NS) is a grassy plant with green or blue flowers and small black seeds, which grows in different regions of southern Europe and some parts of Asia.[16] The seeds of NS are the source of the active ingredients of this plant and contain 30-40% fixed oil, 0.5-1.5% essential oil with unpleasant odor, various sugars, proteins, and pharmacologically active ingredients like thymoquinone (TQ), ditimoquinone (DTQ), and nigellin.[16–21] The plant has been documented in traditional medicine as having healing power.[22] It has been used in folk medicine in the Middle East and Far East for many years as a traditional remedy for a wide range of illnesses including bronchial asthma, headache, dysentery, infections, obesity, back pain, hypertension, and gastrointestinal problems.[22] Finally, there is a common Islamic belief that the NS is a useful tool that has beneficial effects in all ailments except death.[22]

The experimental studies have also confirmed some pharmacological effects of NS seeds and TQ. It has been reported that the extract of NS seeds and TQ have inhibitory effect on NO production and inducible NO synthase (NOS) expression.[16,23,24] Antioxidant effects of NS and TQ in CCl4-induced oxidative injury in rat liver,[25] isolated rat hepatocytes,[26] hypercholesterolemic rats,[27] and gentamicin-[28] and cyclosporine-induced kidney injury have also been reported.[28,29] Hosseinzadeh et al.[30] found that NS oil and TQ have antioxidant properties during cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rat hippocampus.[30] The analgesic effects of NS and its effects on tolerance to morphine also have been reported.[31,32] Interaction of NS or its components with the neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, acetylcholine, GABA, histamine, and NO on the rewarding properties of morphine has been reported.[32–35]

Based on the properties of NS which have been reported in traditional medicine and in experimental studies, the present study was designed to evaluate the possible effects of hydro-alcoholic extract of NS on the CPP induced by morphine in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of the plant extract

Powdered seeds (100 g) of NS were extracted in a Soxhlet extractor with ethanol (70%). The resulting extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and kept at −20°C until use (yield 32%). Before use, the NS extract was dissolved in saline.[36–38]

Animals

Eighty male Wistar rats, 8 weeks old and weighing 220 ± 20 g, were obtained from the Animal Center of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Mashhad, Iran). Animals were kept at 22 ± 2°C and 12 h light/dark cycle on at 07:00 h. They were randomly divided into eight groups and treated according to the experimental protocol. All measurements were performed at 10:00-14:00 h. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Animal handling and all related procedures were carried out in accordance with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Ethical Committee Acts.

CPP apparatus

The CPP apparatus is a three-compartment chamber. Two main compartments of the apparatus (compartments A and B) were identical in size but differed in shading and texture. Compartment A was painted white and had a smooth floor, and compartment B was painted black and white strip and had metal grid floor. The third or small compartment was an unpainted tunnel which separated the two main compartments. During the conditioning phase, the compartments were isolated by removable partition.[9,39,40]

Behavioral procedures

The CPP experiment consisted of a 6-day schedule with three phases: Pre-conditioning (phase 1), conditioning (phase 2), and post-conditioning (phase 3). On day 0, the rats were allowed to move freely in the three chambers for 45 min. In the pre-conditioning phase (day 1), rats were placed in the middle of the neutral compartment area and allowed to move freely in the three compartments and the time spent in each compartment during the 15 min was recorded.

In phase 2 (days 2-4), the animals were treated with alternative injections of morphine (5 mg/kg, s.c.) and saline. On day 2, the animals received a single dose of morphine in the morning (09:00-12:00 h) and were immediately placed in compartment A for 45 min. In the afternoon (16:00-18:00 h), the animals received a single injection of saline and were placed in compartment B for 45 min. On day 3, the animals received saline injections in the morning (compartment B) and morphine in the afternoon (compartment A). The 4th day of protocol was the same as that of day 2. In the saline group, the rats received saline in compartment A as well as in compartment B. In the post-conditioning phase (day 5), the barriers were removed and the rats were placed in the neutral compartment and allowed to move freely for 15 min. The time spent in each compartment was computed. Change in preference was identified as the difference (in second) between the time spent in compartment A on the pre-conditioning day and the time spent in this compartment on the post-conditioning day. This time reflects the relative rewarding properties of morphine.[12,40]

Experimental groups

Rats were divided into the following groups:

Group 1 (control) animals received saline in both compartments A and B of CPP apparatus

Group 2 (morphine; Mor) animals received morphine in compartment A and saline in compartment B

Group 3 (Mor + NS 200): Morphine was injected on the conditioning days and finally 200 mg/kg of NS was injected on the post-conditioning day

Group 4 (Mor + NS 400): Morphine was injected on the conditioning days and finally 400 mg/kg of NS was injected on the post-conditioning day

Groups 5) Mor + NS 200) animals were treated with 200 mg/kg of NS before each injection of morphine in compartment A during the conditioning phase

Group 6 (Mor + NS 400) animals were treated with 400 mg/kg of NS before each injection of morphine in compartment A during the conditioning phase

Group 7 (NS 200) animals were injected 200 mg/kg of the NS extract during the conditioning phase instead of morphine

Group 8 (NS 400) animals were injected 400 mg/kg of the NS extract during the conditioning phase instead of morphine.

Experimental design

Experiment 1: Evaluation of the effect NS extract on expression of morphine-induced CPP

To determine the effects of NS extract on the expression of the reinforcing properties of morphine, different groups of rats were injected with 200 and 400 mg/kg of the extract on the test day, 60 min before the post-conditioning phase.

Experiment 2: Evaluation of the effect of NS extract on acquisition of morphine-induced CPP

To examine the influence of NS extract on the acquisition of morphine-induced CPP, the rats received NS extract (200 and 400 mg/kg, i.p.) or its vehicle 60 min before each morphine injection during the conditioning phase, as described above.

Experiment 3: Evaluation of the conditioning effects of NS extract

To examine the conditioning effect of NS extract, the rats received NS extract (200 or 400 mg/kg, i.p.) instead of morphine 60 min before they were placed in compartment A in the conditioning phase, as described above.

RESULTS

The effects of NS extract on expression of morphine-induced CPP

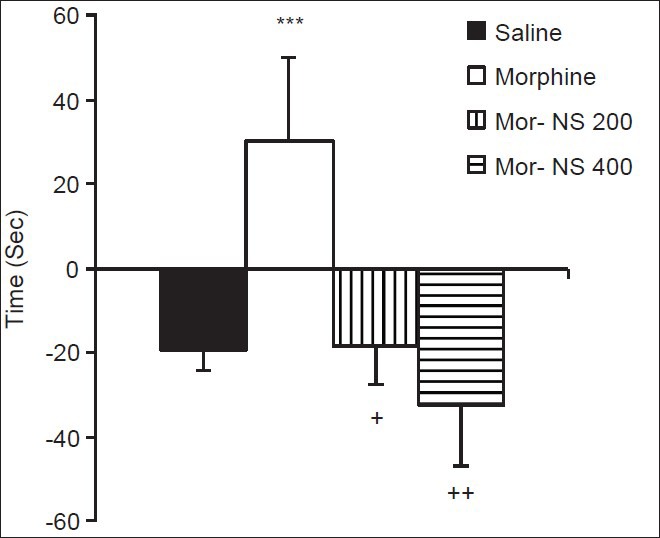

Administration of morphine increased while saline decreased the difference in occupancy time in compartment A during the pre-conditioning day and the post-conditioning day. This difference in the morphine group was significantly greater than in the saline group (P < 0.001) [Figure 1]. This shows that 5 mg/kg of morphine could produce place preference. In the NS 200 + Mor and NS 400 + Mor groups (groups 3 and 4, respectively), administration of both doses of NS on the test day reduced the difference in occupancy time in compartment A during pre-conditioning and post-conditioning compared to the morphine group (P < 0.05) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The effects of NS extract on the expression of morphine-induced CPP (Rats in group 1 (control) received saline in both A and B compartments. In group 2 animals, morphine was injected in compartment A and saline in compartment B. Group 3 (Mor + NS 200) and group 4 (Mor + NS 400) animals were injected with morphine on conditioning days and finally were injected with 200 or 400 mg/kg of NS on post-conditioning day. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of the difference in time spent in compartment A between the pre-conditioning and post-conditioning phases (n = 10 in each group). ***P < 0.001 compared to the saline group; +P < 0.05, ++P<0.01 compared to the morphine group)

The effect of NS extract on acquisition of morphine-induced CPP

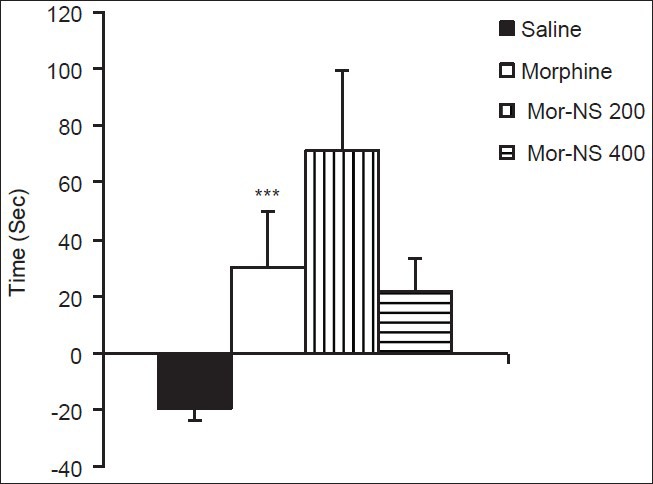

In Mor + NS 200 and Mor + NS 400 groups (groups 5 and 6, respectively), administration of either doses of NS 60 min before each morphine injection during the conditioning phase had no significant effect on the difference in occupancy time in compartment A during pre-conditioning and post-conditioning compared to the morphine group [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The effect of NS extract on acquisition of morphine-induced CPP (Mor + NS 200 and Mor + NS 400 groups were treated with 200 or 400 mg/kg of NS, respectively, before each injection of morphine in compartment A during the conditioning phase. Administration of either dose of NS 60 min before each morphine injection during the conditioning phase had no significant effect on the difference in occupancy time in compartment A during pre-conditioning and post-conditioning phases, compared to the morphine group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of the difference in time spent in compartment A between the pre-conditioning and post-conditioning phases (n = 10 in each group))

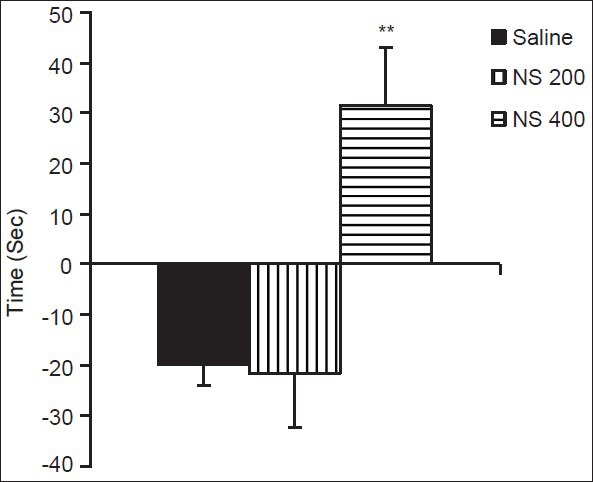

Conditioning effects of NS extract

As Figure 3 shows, 400 mg/kg of the extract results in an increase in the occupancy time in compartment A compared to saline group (P < 0.01); however, 200 mg/kg of the extract was not effective.

Figure 3.

Conditioning effects of NS extract (Rats in the saline group received saline in both A and B compartments. The animals of NS 200 and NS 400 groups were injected with the NS extract (200 or 400 mg/kg, i.p.) during the conditioning phase, 60 min before placing them in compartment A. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of the difference in time spent in compartment A between pre-conditioning and post-conditioning phases (n = 10 in each group). **P < 0.01 compared to the saline group)

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the effect of NS extract on morphine-induced CPP was investigated. Our results indicated that the hydro-alcoholic extract of NS has conditioning effect and decreased expression, but has no significant effect on the acquisition of morphine CPP.

The pharmacological analysis using selective opioid receptor antagonists revealed that the block of supraspinal μ- and k-, but not б-opioid, receptor subtypes attenuated TQ antinociception in the early phase of the formalin test, while none of these receptor subtypes was implicated in the antinociceptive effect of TQ in the late phase response. There is evidence that the early phase of the response to formalin can be inhibited by stimulation of central opioid receptors, while inhibition of the late phase response involves both peripheral and central opioid receptors.[41] The reversal of TQ antinociception in the early phase by Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injections of μ- and k-opioid receptor antagonists suggests that the effect of TQ is at least partly mediated by stimulation of supraspinal μ- and k-opioid receptors.[42,43] It has also been postulated that NS oil and TQ produce antinociception in the formalin test by releasing endogenous opioid peptides in the central nervous system, and cause antinociceptive tolerance following repeated administration.[31] It was also shown that the antinociceptive effect of morphine was reduced in TQ- and NS oil-pretreated mice[31]

The antioxidant effects of NS and its main component TQ have been well documented in several experimental models. It has been shown that NS extract and TQ attenuated oxidative stress and neuropathy in diabetic rats.[44] The oxidative stress has also been considered as a cause or a consequence of addiction.[45,46] Therefore, it might be suggested that the beneficial effect of NS that was seen in the present study might in part be due to this mechanism. Hosseinzadeh et al. have also shown that NS and TQ prevented lipid peroxidation increment in hippocampal proteins following global cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury model in rats.[30] Antiepileptic effect of NS and its ability to inhibit excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures has been reported.[47] Neuroprotective effects of NS in an experimental model of spinal cord injury in rats have also been attributed to its antioxidant capability.[48] It has been demonstrated that some natural products with the antioxidant activity also have beneficial effects in morphine tolerance or dependence.[49,50]

It has also been reported that TQ or NS extract modulate the functions of cholinergic system.[33,34,51] On the other hand, the contribution of this neurotransmitter system in the rewarding properties of morphine, tolerance to morphine, and morphine dependence has been well documented.[52–54] Therefore, the interaction of the components of NS to modulate the effect of morphine might be suggested.

It has been demonstrated that the inhibitory effects of NS oil on the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in mice were antagonized by co-administration of the precursor of NO, l-arginine, while they were enhanced by concurrent administration of the NOS inhibitors, l-NAME, amino guanidine, or 7-nitroindazole (7-NI).[32] It has also been reported that the aqueous extract of NS seeds inhibits NO production[24] and that TQ suppresses NO production and inducible NOS expression[23] in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rat peritoneal macrophages. On the other hand, it has also been suggested that NO may be implicated in the action of opioids; for instance, it has been demonstrated that inhibitors of NOS can prevent morphine tolerance[55] and attenuate development and expression of the abstinence syndrome.[56] Sahraei et al. showed that both acute and chronic administration of l-arginine reduced and l-NAME increased morphine self-administration. They concluded that NO may have a role in morphine self-administration.[57]

The mediating role of glutamate and its receptors in the effects of NS in the nervous system, including its effects on morphine tolerance have also been reported. It was shown that the attenuating effects of NS oil on the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in mice were enhanced by co-administration of MK-801.[32] On the other hand, the role of glutamatergic system in the rewarding properties of morphine and the complications of using morphine, including tolerance and addiction have been well documented.[58,59] Therefore, the interaction of NS and glutamatergic system may also be considered as another possible mechanism for the results of the present study. However, each of the mentioned mechanisms needs to be investigated further.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study showed that the hydro-alcoholic extract of NS has no effect on acquisition but significantly reduced the expression of morphine-induced CPP. In addition, this study indicated that similar to morphine, NS can induce place preference in rats.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Presidency of Research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Savage SR. Long-term opioid therapy: Assessment of consequences and risks. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:274–86. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prus AJ, James JR, Rosecrans JA. Conditioned Place Preference. In: Buccafusco JJ, editor. Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2009. Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat protoc. 2006;1:1662–70. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diana M, Muntoni AL, Pistis M, Melis M, Gessa GL. Lasting reduction in mesolimbic dopamine neuronal activity after morphine withdrawal. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1037–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosseini M, Sharifi MR, Alaei H, Shafei MN, Karimooy HA. Effects of angiotensin II and captopril on rewarding properties of morphine. Indian J Exp Biol. 2007;45:770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarrindast MR, Ahmadi S, Haeri-Rohani A, Rezayof A, Jafari MR, Jafari-Sabet M. GABA (A) receptors in the basolateral amygdala are involved in mediating morphine reward. Brain Res. 2004;1006:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosseini H, Abrisham SM, Jomeh H, Kermani-Alghoraishi M, Ghahramani R, Mozayan MR. The comparison of intraarticular morphine-bupivacaine and tramadol-bupivacaine in postoperative analgesia after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1839–44. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1791-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosseini M, Alaei HA, Havakhah S, Neemati Karimooy HA, Gholamnezhad Z. Effects of microinjection of angiotensin II and captopril to VTA on morphine self-administration in rats. Acta Biol Hung. 2009;60:241–52. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.60.2009.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosseini M, Alaei HA, Headari R, Eslamizadeh MJ. Effects of microinjection of angiotensin II and captopril into nucleus accumbens on morphine self-administration in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2009;47:361–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosseini M, Alaei HA, Naderi A, Sharifi MR, Zahed R. Treadmill exercise reduces self-administration of morphine in male rats. Pathophysiology. 2009;16:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseini M, Sharifi MR, Alaei H, Shafei MN, Karimooy HA. Effects of angiotensin II and captopril on rewarding properties of morphine. Indian J Exp Biol. 2007;45:770–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseini M, Taiarani Z, Hadjzadeh MA, Salehabadi S, Tehranipour M, Alaei HA. Different responses of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on morphine-induced antinociception in male and female rats. Pathophysiology. 2011;18:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosseini M, Taiarani Z, Karami R, Abad AA. The effect of chronic administration of L-arginine and L-NAME on morphine-induced antinociception in ovariectomized rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:541–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karami R, Hosseini M, Khodabandehloo F, Khatami L, Taiarani Z. Different effects of L-arginine on morphine tolerance in sham and ovariectomized female mice. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:1016–23. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1100029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boskabady MH, Shirmohammadi B, Jandaghi P, Kiani S. Possible mechanism (s) for relaxant effect of aqueous and macerated extracts from Nigella sativa on tracheal chains of guinea pig. BMC Pharmacol. 2004;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boskabady MH, Farhadi J. The possible prophylactic effect of Nigella sativa seed aqueous extract on respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function tests on chemical war victims: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:1137–44. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boskabady MH, Javan H, Sajady M, Rakhshandeh H. The possible prophylactic effect of Nigella sativa seed extract in asthmatic patients. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21:559–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boskabady MH, Keyhanmanesh R, Saadatloo MA. Relaxant effects of different fractions from Nigella sativa L. on guinea pig tracheal chains and its possible mechanism (s) Indian J Exp Biol. 2008;46:805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boskabady MH, Mohsenpoor N, Takaloo L. Antiasthmatic effect of Nigella sativa in airways of asthmatic patients. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:707–13. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boskabady MH, Shafei MN, Parsaee H. Effects of aqueous and macerated extracts from Nigella sativa on guinea pig isolated heart activity. Pharmazie. 2005;60:943–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali BH, Blunden G. Pharmacological and toxicological properties of Nigella sativa. Phytother Res. 2003;17:299–305. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Mahmoudy A, Matsuyama H, Borgan MA, Shimizu Y, El-Sayed MG, Minamoto N, et al. Thymoquinone suppresses expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1603–11. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmood MS, Gilani AH, Khwaja A, Rashid A, Ashfaq MK. The in vitro effect of aqueous extract of Nigella sativa seeds on nitric oxide production. Phytother Res. 2003;17:921–4. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanter M, Coskun O, Uysal H. The antioxidative and antihistaminic effect of Nigella sativa and its major constituent, thymoquinone on ethanol-induced gastric mucosal damage. Arch Toxicol. 2006;80:217–24. doi: 10.1007/s00204-005-0037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansour MA, Ginawi OT, El-Hadiyah T, El-Khatib AS, Al-Shabanah OA, Al-Sawaf HA. Effects of volatile oil constituents of Nigella sativa on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice: Evidence for antioxidant effects of thymoquinone. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2001;110:239–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ismail M, Al-Naqeep G, Chan KW. Nigella sativa thymoquinone-rich fraction greatly improves plasma antioxidant capacity and expression of antioxidant genes in hypercholesterolemic rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaman I, Balikci E. Protective effects of nigella sativa against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2010;62:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uz E, Bayrak O, Kaya A, Bayrak R, Uz B, Turgut FH, et al. Nigella sativa oil for prevention of chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity: An experimental model. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:517–22. doi: 10.1159/000114004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosseinzadeh H, Parvardeh S, Asl MN, Sadeghnia HR, Ziaee T. Effect of thymoquinone and Nigella sativa seeds oil on lipid peroxidation level during global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hippocampus. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdel-Fattah AM, Matsumoto K, Watanabe H. Antinociceptive effects of Nigella sativa oil and its major component, thymoquinone, in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;400:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Zaher AO, Abdel-Rahman MS, FM EL. Blockade of nitric oxide overproduction and oxidative stress by Nigella sativa oil attenuates morphine-induced tolerance and dependence in mice. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:1557–65. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.el Tahir KE, Ashour MM, al-Harbi MM. The respiratory effects of the volatile oil of the black seed (Nigella sativa) in guinea-pigs: Elucidation of the mechanism (s) of action. Gen Pharmacol. 1993;24:1115–22. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jukic M, Politeo O, Maksimovic M, Milos M. In vitro acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties of thymol, carvacrol and their derivatives thymoquinone and thymohydroquinone. Phytother Res. 2007;21:259–61. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Naggar T, Gómez-Serranillos MP, Palomino OM, Arce C, Carretero ME. Nigella sativa L. seed extract modulates the neurotransmitter amino acids release in cultured neurons in vitro. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/398312. 398312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mousavi SH, Tayarani-Najaran Z, Asghari M, Sadeghnia HR. Protective effect of Nigella sativa extract and thymoquinone on serum/glucose deprivation-induced PC12 cells death. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:591–8. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosseini M, Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar M, Sadeghnia HR, Rakhshandeh H. Effects of different extracts of Rosa damascena on pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in mice. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2011;9:1118–24. doi: 10.3736/jcim20111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rakhshandah H, Hosseini M. Potentiation of pentobarbital hypnosis by Rosa damascena in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44:910–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosseini M, Nemati Karimooy HA, Alaei H, Eslamizadeh MJ. Effect of losartan on conditioned place preference induced by morphine. Pharmacologyonline. 2008;3:968–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alaei H, Hosseini M. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor captopril modifies conditioned place preference induced by morphine and morphine withdrawal signs in rats. Pathophysiology. 2007;14:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oluyomi AO, Hart SL, Smith TW. Differential antinociceptive effects of morphine and methylmorphine in the formalin test. Pain. 1992;49:415–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90249-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdel-Fattah AM, Matsumoto K, Watanabe H. Antinociceptive effects of Nigella sativa oil and its major component, thymoquinone, in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;400:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paarakh PM. Nigella sativa Linn: A comprehensive review. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:409–29. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamdy NM, Taha RA. Effects of Nigella sativa oil and thymoquinone on oxidative stress and neuropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacology. 2009;84:127–34. doi: 10.1159/000234466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guzman DC, Vazquez IE, Brizuela NO, Alvarez RG, Mejia GB, Garcia EH, et al. Assessment of oxidative damage induced by acute doses of morphine sulfate in postnatal and adult rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:549–54. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panchenko LF, Pirozhkov SV, Nadezhdin AV, Baronets V, Usmanova NN. Lipid peroxidation, peroxyl radical-scavenging system of plasma and liver and heart pathology in adolescence heroin users. Vopr Med Khim. 1999;45:501–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilhan A, Gurel A, Armutcu F, Kamisli S, Iraz M. Antiepileptogenic and antioxidant effects of Nigella sativa oil against pentylenetetrazol-induced kindling in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:456–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanter M, Coskun O, Kalayci M, Buyukbas S, Cagavi F. Neuroprotective effects of Nigella sativa on experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2006;25:127–33. doi: 10.1191/0960327106ht608oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alaei H, Esmaeili M, Nasimi A, Pourshanazari A. Ascorbic acid decreases morphine self-administration and withdrawal symptoms in rats. Pathophysiology. 2005;12:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajaei Z, Alaei H, Nasimi A, Amini H, Ahmadiani A. Ascorbate reduces morphine-induced extracellular DOPAC level in the nucleus accumbens: A microdialysis study in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1053:62–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wienkotter N, Hopner D, Schutte U, Bauer K, Begrow F, El-Dakhakhny M, et al. The effect of nigellone and thymoquinone on inhibiting trachea contraction and mucociliary clearance. Planta Med. 2008;74:105–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang J, Chen Y, Carlson S, Li L, Hu X, Ma Y. Interactive effects of morphine and scopolamine, MK-801, propanolol on spatial working memory in rhesus monkeys. Neurosci Lett. 2012;523:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avena NM, Rada PV. Cholinergic modulation of food and drug satiety and withdrawal. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:332–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishida S, Kawasaki Y, Araki H, Asanuma M, Matsunaga H, Sendo T, et al. Alpha7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the central amygdaloid nucleus alter naloxone-induced withdrawal following a single exposure to morphine. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:923–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kolesnikov YA, Pick CG, Pasternak GW. NG-nitro-L-arginine prevents morphine tolerance. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221:399–400. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90732-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimes AS, Vaupel DB, London ED. Attenuation of some signs of opioid withdrawal by inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:521–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02244904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sahraei H, Poorheidari G, Foadaddini M, Khoshbaten A, Asgari A, Noroozzadeh A, et al. Effects of nitric oxide on morphine self-administration in rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garzon J, Rodriguez-Munoz M, Sanchez-Blazquez P. Direct association of Mu-opioid and NMDA glutamate receptors supports their cross-regulation: Molecular implications for opioid tolerance. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2012;5:199–226. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205030199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parkitna JR, Solecki W, Golembiowska K, Tokarski K, Kubik J, Golda S, et al. Glutamate input to noradrenergic neurons plays an essential role in the development of morphine dependence and psychomotor sensitization. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;1:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]