Abstract

Background:

There are various techniques developed to treat the exposed roots, a recent innovation in dentistry is the use of second generation platelet concentrate which is an autologous platelet-rich fibrin gel (PRF) with growth factors and cicatricial properties for root coverage procedures. Therefore, the present research was undertaken to study the additional benefits of PRF when used along with coronally advanced flap (CAF).

Materials and Methods:

Total of 15 systemically healthy subjects presenting bilateral isolated Miller's class I and II recession were enrolled into the study. Each patient was randomly treated with a combination of CAF along with a platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membrane on the test site and CAF alone on the control site. Recession depth, clinical attachment level (CAL), and width of keratinized gingiva (WKG) were compared with baseline at 1, 3, and 6 months between test and control sites.

Results:

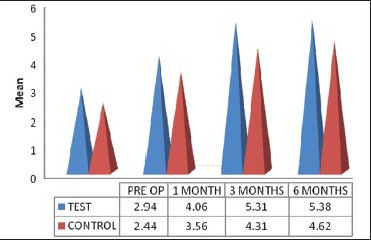

Mean percentage root coverage in the test group after 1, 3, and 6 months was 34.58, 70.73, and 100, respectively. Differences between the control and test groups were statistically significant. This study also showed a statistically significant increase in WKG in the test group (2.94 ± 0.77 at baseline to 5.38 ± 1.67 at 6 months).

Conclusion:

CAF is a predictable treatment for isolated Miller's class I and II recession defects. The addition of PRF membrane with CAF provides superior root coverage with additional benefits of gain in CAL and WKG at 6 months postoperatively.

Keywords: Coronally advanced flap, gingival recession, platelet rich fibrin, root coverage procedures

INTRODUCTION

Gingival recession is the displacement of the gingival margin apical to the cemento-enamel junction with oral exposure of the root surface.[1] Gingival recession may occur on one or all surfaces of a tooth and may affect a localized area or have a more generalized distribution within a dentition. Although many conditions or behavioral habits are associated with an increased risk for gingival recession, the common etiological factor appears to be the development of inflammation within the gingival connective tissue. This inflammation is thought to result in the degeneration of gingival connective tissue, this eventually undermines the gingival tissues, resulting in shrinkage and recession of the gingival tissues.[2] The resulting exposure is not aesthetically pleasing and may lead to root hypersensitivity and root caries.[3]

Since mid-20th century, different techniques like free autogenous grafts, pedicle grafts including rotational flaps, coronally advanced flaps (CAFs), semilunar flaps have been advocated to cover denuded root surfaces. Combination techniques using autogenous or allograft and guided tissue regeneration membranes were developed later to correct muco-gingival defects.[4] A recent innovation in dentistry is the use of second-generation platelet concentrate which is an autologous platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) gel with growth factors and cicatricial properties for root coverage procedures.[5] Therefore, the present research was undertaken to study the additional benefits of PRF when used along with a CAF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifteen subjects aged between 18 and 35 years who visited the outpatient Department of Periodontics, St. Joseph Dental College and Hospital, Eluru, Andhra Pradesh, and having bilateral buccal Miller's class I and class II gingival recessions with no radiographic interdental bone loss were selected for the study. The benefits and drawbacks of the study explained to the patients and upon signing an informed consent, the patients were recruited for the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the same institution.

Exclusion criteria included:

Patients with known systemic diseases or immune deficiency,

Patients on medication, psychiatric disorders and pregnancy,

History of smoking,

Inability or unwillingness to complete the trial and who are participating in another clinical trial.

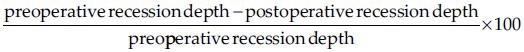

A randomized split mouth clinical design was used with 30 sites in 15 patients (2 sites in each patient) and the selected sites were divided into two groups which were categorized as Group-I (Control group-15 sites were treated with CAF alone) and Group-II (Test group-15 sites treated with coronally advanced flap + platelet-rich fibrin membrane). All subjects received clinical periodontal examination by a single examiner to avoid inter-examiner variability. The following periodontal parameters like plaque index (Loe and Sillness 1962), recession depth (RD), clinical attachment level (CAL), width of keratinized gingiva (WKG), and the percentage of root coverage were recorded at base line, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively using William's periodontal probe [Figures 1 and 2]. The RD was measured at mid-facial region of the tooth from CEJ to the free gingival margin. The clinical attachment level was measured from a fixed reference point (CEJ) to the base of the sulcus using customized stent. The WKG was determined by subtracting the RD from the CEJ- MGJ (mucogingival junction). The percentage of root coverage was calculated according to the following formula.[6]

Figure 1.

Two weeks postoperative view

Figure 2.

6 month postoperative

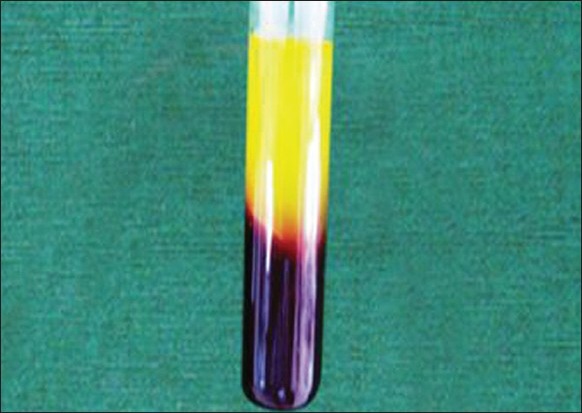

Preparation of PRF membrane

Preoperatively, 10 ml of intravenous blood was collected in a syringe, later transferred into a test tube and centrifuged immediately without the addition of anticoagulant at 3000 revolutions per minute for 10 minutes. The absence of anticoagulant initiates the activation of platelets when they come in contact with the walls of the test tube. The resultant product consists of the three layers–top most layer consisting of acellular plasma, PRF clot in the middle, red blood cells at the bottom [Figure 3]. PRF clot was separated from other two layers and PRF was obtained in the form of a membrane by squeezing out the fluids in the fibrin clot [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Centrifuged blood sample

Figure 4.

Platelet-rich fibrin membrane

Presurgical procedure

Thorough scaling and root planing was done on the selected patients after initial examination. Detailed instructions regarding self-performed plaque control measures were given. One week after phase I therapy, only those patients who maintained optimum oral hygiene were subjected to surgical procedure after recording all the baseline measurements.

Surgical procedure

Two gingival recession sites in each patient were randomly assigned as either test site or control site by flipping the coin. In control sites, the surgical site was prepared by placing two vertical incisions beyond the mucogingival junction followed by placing an internal bevel incision. Mucoperiosteal flap was raised and coronally advanced so that its gingival margin lies 1 mm coronal to the cementoenamel junction and sutured using sling sutures. The surgical area was protected using a non-eugenol dressing (Coe-Pack, GC America Inc., USA) [Figures 5 and 6]. In test group sites, the surgical sites preparation was similar to control sites and the prepared PRF membrane was placed over the denuded root surface just below the CEJ [Figure 7]. The flap closure and wound protection was done similar to control sites.

Figure 5.

Preoperative site showing Miller's class I recession

Figure 6.

Prepared surgical site

Figure 7.

PRF membrane placed over the site

After surgery, postoperative instructions were given including a recommendation to refrain from mechanical cleaning on the surgical areas and all the patients were prescribed with Cap. Amoxicillin 500 mg tid, tab. Ibuprofen 400 mg three times a day (7 days postoperative) and 0.2% Chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily, for a period of 1 month.

Statistical analysis

All 15 patients who were included in the study received the treatment and turned up regularly for re-evaluation. The statistical analysis was performed using commercially available computer software. A subject-level analysis was performed for each parameter. Mean and standard deviation for the clinical variables were calculated for each treatment. The significance of the difference within and between groups before and after treatment was evaluated with the paired-samples t test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Plaque index

The mean plaque index score at baseline was 2.04 ± 0.37 which was reduced to 0.52 ± 0.37 at 3 months and 0.20 ± 0.11 at 6 months post surgically showed a statistically significant (P < 0.05) mean reduction in plaque index scores.

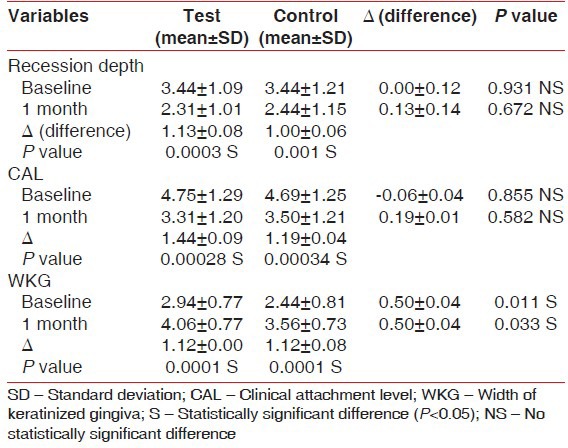

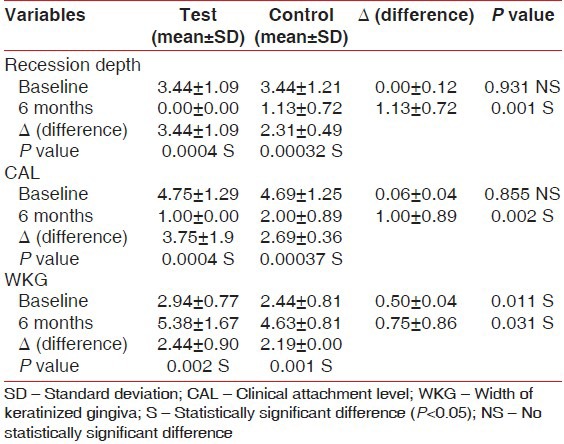

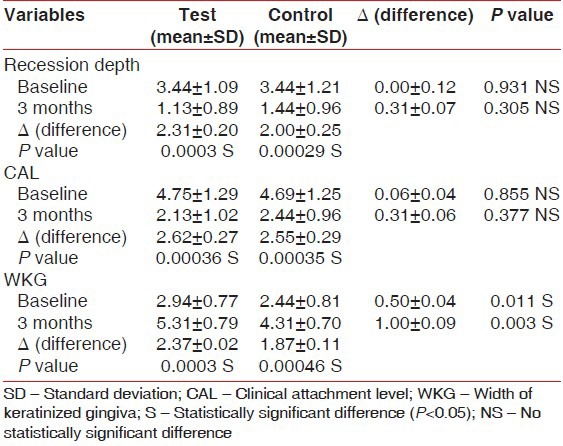

Recession depth

The mean recession depth in Group-I (control site) at baseline was 3.44 ± 1.21 mm, after 1, 3, and 6 months which was reduced to 2.44 ± 1.15, 1.44 ± 0.96, 1.13 ± 0.72 mm, respectively [Tables 1–3]. The mean recession depth in Group-II (test site) at baseline was 3.44 ± 1.09 mm, which was reduced to 2.31 ± 1.01, 1.13 ± 0.89, 0.00 ± 0.00 mm at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively, the difference was statistically significant [Tables 1–3].

Table 1.

Comparison of parameters at 1 month postoperatively

Table 3.

Comparison at 6months postoperatively

Table 2.

Comparison of parameters at 3 months postoperatively

An intergroup comparison of mean reduction in recession depth at 1 and 3 months showed a P value of 0.672 and 0.305, respectively, which is statistically not significant (P > 0.05). But, a similar comparison at 6 months post-operatively showed a P value of 0.001 which is statistically significant [Tables 1 and 3].

Clinical attachment level

The mean clinical attachment level in Group-I at baseline was 4.69 ± 1.25 mm which was reduced to 3.50 ± 1.21, 2.44 ± 0.96, 2.00 ± 0.89 mm post surgically at 1, 3, 6 months, respectively, in Group-II at baseline was 4.75 ± 1.29 mm which was reduced to 3.31 ± 1.20, 2.13 ± 1.02, 1.00 ± 0.00 mm post surgically at 1, 3, 6 months, respectively, showing a statistically significant mean reduction in clinical attachment level (P < 0.05) [Tables 1–3]. The intergroup comparison at 1 and 3 months showed a P value of 0.582 and 0.377, respectively, which is statistically not significant (P > 0.05). Similarly, at 6 months a P value is 0.002, which is statistically significant (P < 0.05) [Tables 1 and 3].

Keratinized gingiva

Both the groups showed an increase in the mean width of keratinized gingiva from baseline to 6 months. A comparison of mean width of keratinized gingiva between the two groups from baseline to 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively showed a P value of 0.033, 0.003, and 0.031 respectively which was statistically significant [Table 3, Graph 1].

Graph 1.

Comparison of mean width of keratinized gingiva

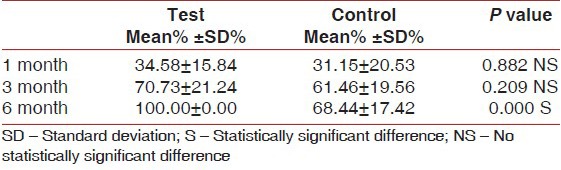

Percentage of root coverage

The mean % reduction in root coverage in Group-I and Group-II at 6 months postoperatively was 68.44 ± 17.42, 100.00 ± 0.00 respectively and showed a P value of 0.00 which is statistically significant (P < 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of percentage of root coverage at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively

DISCUSSION

Gingival recession may be a concern for patients with a high lip smile line. Studies on this surgical challenge is mostly concerned with the treatment of Miller's class I and II recession defects.[7] Fifteen systematically healthy subjects aged between 18 and 35 years presenting with identical bilateral isolated Miller's class I and II were enrolled into the study. This split mouth design helped to avoid variations in characteristics between patients. RD, CAL, and WKG were measured at baseline, 1, 3, 6 months at test and control sites. A comparison was done post surgically within and between test and control sites.

CAF is a predictable procedure to treat Miller's class I mucogingival defects[8] and initial gingival thickness was the most significant factor associated with complete root coverage by analyzing the factors like recession depth, probing depth, width of keratinized gingiva, clinical attachment level, and gingival thickness. Therefore, this study is conducted to see the additional benefits of using PRF along with the standard procedure of CAF which gives the more predictable results.

The autologous PRF clot was used initially in implant surgery to improve bone healing. Due to the lack of scientifically proven clinical benefit, the homogeneous fibrin network is considered by the promoters to be a healing biomaterial and is commonly used in implant and plastic periodontal surgery procedures to enhance bone regeneration and soft tissue wound healing.[7] Compared to PRP, there is very little literature available about the biologic properties of PRF. However, it contains platelets, growth factors, and cytokines that may enhance the healing potential of bone as well as soft tissues.[7]

The percentage of root coverage for test group at 6 months is statistically significant when compared to the control group. This is in accordance to the previous studies.[8,9,10] Sling sutures were used in this study to allow stabilization of the flap margin at or above the cementoenamel junction during the first 2 weeks of wound healing similar to theprevious study.[11]

The addition of PRF as a membrane to CAF showed an increase in width of keratinized gingiva and a decrease in clinical attachment loss, recession depth, which was statistically significant at 6 months. This in accordance with study done by Jankovic et al., who evaluated and compared the clinical effectiveness of platelet rich plasma and connective tissue graft in the treatment of gingival recession.[12]

In studies evaluating the coronally repositioned flaps together with free connective grafts by Wennstorm et al., Pini Prato and Lee et al., it has been reported that long-term increase in width of keratinized gingiva associated with an apical shift of the mucogingival junction.[13,14,15]

In our study, a significant increase in the width of keratinized gingiva was observed at all periods (1,3,6 months) compared to the baseline values for both the study groups.

In our study, a significant gain in CAL was observed in both the groups. These outcomes are also in agreement with literature reports for the treatment of gingival recession with a connective tissue graft and CAF.[16,17,18]

The secretion profile of three isoforms of cytokines [platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) and insulin growth factor-1(IGF-1)] within the different parts of the PRF collection tube and a whole range of concentrated platelet rich plasma were studied. From their comparative biochemical analysis, authors came to the conclusion that PRF consists of an intrinsic assembly of cytokines, glycemic chains, and structural glycoproteins enmeshed in a slowly polymerized fibrin network having synergistic effects on healing processes-1) and insulin growth factor-1(IGF-1)] within the different parts of the PRF collection tube and a whole range of concentrated platelet rich plasma were studied. From their comparative biochemical analysis, authors came to the conclusion that PRF consists of an intrinsic assembly of cytokines, glycemic chains, and structural glycoproteins enmeshed in a slowly polymerized fibrin network having synergistic effects on healing processes.[19] Therefore, PRF can be considered as not only a new generation of platelet gel but a completely usable healing concentrate gel. They also evaluated the quantity of five significant cell mediators within PRP supernatant and PRF clot exudates, three proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-4), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by collecting blood from fifteen 20-28 year old healthy non-smoker males and stated that the cytokine concentrations were high in PRF clot exudates than in plasma and serum samples with the exception that the concentration of VEGF is significantly high in serum samples.[20]

It is necessary to look further into platelet and inflammatory features of this biomaterial. Only a perfect understanding of its components and their significance will enable us to comprehend the clinical results obtained and subsequently extend the fields of therapeutic application of this protocol.

CONCLUSION

This controlled, randomized, split mouth design for the treatment of bilateral isolated Miller's class I and II gingival recessions indicated that CAF surgery alone or in combination with PRF are effective procedures to cover denuded roots. The data obtained from a combination of CAF-PRF after a period of 6 months showed additional benefits along with mean root coverage in the treatment of Miller's class I and II gingival recessions when compared with the CAF technique alone.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jan LW, Giovanni Z. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures?: A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen E, Irwin C, Ziada H, Mullally B, Byrne PJ. Periodontics: The management of gingival recession. (538-40).Dent Update. 2007;34:534–6. doi: 10.12968/denu.2007.34.9.534. 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moawia MK, Robert EC. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anilkumar K, Geetha A, Umasudhakar, Ramakrishnan T, Vijayalakshmi R, Pameela E. Platelet-rich-fibrin: A novel root coverage approach. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:50–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.51897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David MD, Joseph C, Antoine D, Steve LD, Anthony JJ, Dohan JM, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shieh AT, Wang HL, O’Neal R, Glickman GN, Mac Neil LM. Development and clinical evaluation of a root coverage procedure using a collagen membrane. J Periodontol. 1997;68:770–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.8.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sofia A, Tibor K, Bruno B, Istvan G, Daniel E. Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:244–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang LH, Neiva RE, Wang HL. Factors affecting the outcomes of coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1729–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eric L, Isabelle M, Guy G. Platelet concentrates: Effects of calcium and thrombin on endothelial cell proliferation and growth factor release. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1498–507. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.10.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YS, Ya PK, Yu HT, Ching-Hua S, Thierry B. In vitro release of growth factors from platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A proposal to optimize the clinical applications of PRF. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lien HH, Hom LW. Sling and tag suturing technique for coronally advanced flap. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27:379–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankovic SM, Zoran AM, Lekovic MC, Bozidar DS, Kenneyy BE. The Use of platelet – rich plasma in combination with connective tissue grafts following treatment of gingival recessions. Periodontal pract today. 2007;4:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennstrom JL, Zucchelli G. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures? A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pini prato G, Clauser C, Cortellini P, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Pagliaro U. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal recessions. A 4-year follow-up study. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1216–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.11.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YM, Kim JY, Seol YJ, Lee YK, Ku Y, Rhyu IC, et al. A 3-year longitudinal evaluation of subpedicle free connective tissue graft for gingival recession coverage. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1412–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.12.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang HL, Bunyaratavej P, Labadie M, Shyr Y, MacNeil RL. Comparision of 2 clinical techniques for treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1301–11. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roccuzzo M, Bunino M, Needleman I, Sanz M. Periodontal plastic surgery for the treatment of localized gingival recession: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:178–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.29.s3.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trombelli L, Scabbia A, Tatakis DN, Calura G. Subpedicle connective tissue graft versus guided tissue regeneration with bioabsorbable membrane in the treatment of human gingival recession defects. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1271–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.11.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second generation platelet concentrate. Part II: Platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second generation platelet concentrate. Part III: Leucocyte activation: A new feature of platelet concentrates? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]