Abstract

To address mitochondrial dysfunction that mediates irreversible visual loss and neurodegeneration of the optic nerve in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS), mice sensitized for EAE were vitreally injected with self-complementary adenoassociated virus (scAAV) containing the NADH-dehydrogenase type-2 (NDI1) complex I gene that quickly expressed in mitochondria of almost all retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Visual function assessed by pattern electroretinograms (PERGs) reduced by half in EAE showed no significant reductions with NDI1. Serial optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed significant inner retinal thinning with EAE that was suppressed by NDI1. Although complex I activity reduced 80% in EAE was not improved by NDI1, in vivo fluorescent probes indicated mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptosis of the EAE retina were reduced by NDI1. Finally, the 42% loss of axons in the EAE optic nerve was ameliorated by NDI1. Targeting the dysfunctional complex I of EAE responsible for loss of respiration, mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptosis may be a novel approach to address neuronal and axonal loss responsible for permanent disability that is unaltered by current disease modifying drugs for MS that target inflammation.

Introduction

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is an inflammatory autoimmune disease of the central nervous system and a highly used animal model for multiple sclerosis (MS). In EAE and MS, frequent sites of involvement include the optic nerve, brain, and spinal cord. Our group has previously demonstrated a high incidence of retrobulbar optic neuritis in DBA1J mice sensitized for EAE with a spinal cord emulsion in complete Freunds adjuvant.1 Traditionally, MS has been viewed as a disorder primarily of immune-mediated demyelination, but more recently increasingly viewed as a neurodegenerative disorder in which neuronal and axonal loss cause irreversible loss of function.2 Recent evidence suggests that the most widely used disease modifying drugs for MS targeting inflammation are ineffective in preventing permanent disability.3 Although focal axonal damage in EAE and MS is partially reversible,4 the underlying molecular mechanisms associated with irreversible neuronal and axonal demise are poorly understood and untreatable, mitochondrial dysfunction is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor.2,5,6,7

Mitochondria play a key role in the pathogenesis of many neurological diseases.8 In our earlier work on EAE, we demonstrated mitochondrial oxidative stress that occurred before the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the CNS resulted in posttranslational modifications in key subunits of complexes I and IV and the mitochondrial heat shock protein chaperone HSP70 critical to the stabilization and translocation of most proteins into the organelle.9 During this same year, Dutta and coworkers implicated mitochondrial involvement in MS lesions where complexes I and III activities were reduced by 61% and 40% respectively.6 Recent reports have also documented impaired activity of several mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes due to large kilobase deletions in the mitochondrial DNA of autopsied MS tissues.4,10 Deficits in complex I are more commonly linked to Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy.11 We had demonstrated that genetically knocking down expression of a critical subunit complex I subunit, NDUFA1 encoded by the nuclear genome, exacerbates optic nerve neurodegeneration and that this defect in complex I decreased energy production and increased oxidative stress leading to neuronal degeneration.12

Restoring mitochondrial impairments in EAE may point to treatments that avert the disability of MS caused by axonal and neuronal demise. By reestablishing electron transfer from NADH to quinone, mitochondrial injury may be ameliorated and neuronal homeostasis maintained. Here, we explore the possibility of suppressing neurodegeneration by expressing mitochondrial NADH-dehydrogenase type-2 (NDI1) in EAE. NDI1 is a single subunit complex I that performs the electron transfer of the 45 subunit mammalian NADH dehydrogenase to quinone without proton pumping.13

Results

scAAV-NDI1 efficiently transduces retinal ganglion cells

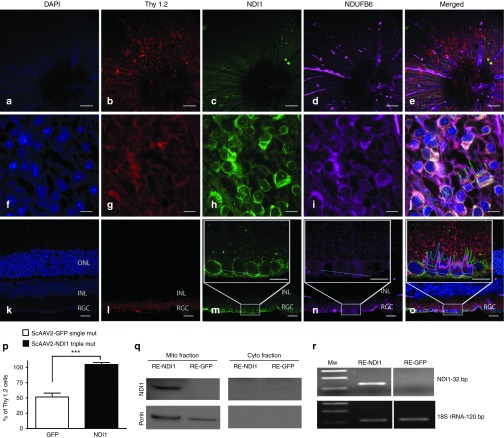

One month after injection of self-complementary adenoassociated virus containing the NDI1 (scAAV-NDI1) into the vitreous cavity of mice, retinal flat mounts focused on the inner retina revealed DAPI-labeled cell nuclei (Figure 1a) identified as retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) by a Thy 1.2 antibody (Figure 1b)–expressed NDI1 (Figure 1c) in mitochondria identified by a complex I subunit antibody against NDUFB6 (Figure 1d) that colocalized with NDI1 (Figure 1e). At a higher magnification, DAPI-labeled cell nuclei (Figure 1f) of Thy 1.2–positive RGCs (Figure 1g) were surrounded by punctuate and perinuclear NDI1 immunofluorescence (Figure 1h). Mitochondria labeled by NDUFB6 (Figure 1i) colocalized with NDI1 in RGCs (Figure 1j). Longitudinal sections of the retina showed nuclei in the RGC, inner nuclear and outer nuclear layers (Figure 1k). Thy 1.2–positive RGCs (Figure 1l) were immunolabeled by NDI1 (Figure 1m). Mitochondria immunolabeled by NDUFB6 were seen in all retinal layers, but predominantly in the RGC layer (Figure 1n) where it colocalized with NDI1 (Figure 1o).

Figure 1.

Ocular expression of NDI1. Retinal flat mounts were performed at 1 month after injection of NDI1 and evaluated for (a) DAPI, (b) Thy 1.2, (c) NDI1, and (d) NDUFB6 with (e) a–d of this same tissue merged. These retinal flat mounts were examined at higher magnification for (f) DAPI, (g) Thy 1.2, (h) NDI1, (i) NDUFB6, and (j) f–i of this same tissue merged. Longitudinal sections of this infected retina were examined for (k) DAPI, (l) Thy 1.2, (m) NDI1, (n) NDUFB6, and (o) k–n merged. The boxed insets show the RGC layer at higher magnification with a colocalization profile plot for all channels over a 25 µm long dotted line. (p) A bar plot of NDI1 delivered by triple mutant (Y444F+Y500F+Y730F) scAAV labeled all Thy 1.2 cells by 7 days. (q) One month after scAAV injections, immunoblots were probed for NDI1. (r) Reverse transcriptase PCR was performed for NDI1 derived transcripts. Scale bars: 100 µm and 10 µm for whole mounts, 25 µm and 10 µm for LS. n = 6 for IF, n = 7 for NDI1 and GFP counting data, n = 12 for western blots, n = 12 for reverse transcriptase PCR, number of repetitions = 3 for each experiment, ***P = 0.0001–0.0009. INL, inner nuclear layer; ON, optic nerve; ONL, outer nuclear layer; RE, retina; RGC, retinal ganglion cell layer; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus.

Quantitative analysis revealed that delivery of NDI1 by triple mutant Y444F+Y500F+Y730F scAAV resulted in transgene expression in all Thy 1.2–labeled RGCs by 7 days after injection, with a count of 12,958 ± 5,185 cells/mm2 (mean ± standard error) NDI1-positive cells to 12,524 ± 5,373 Thy 1.2–positive RGCs/mm2. The expression efficiency of scAAV-GFP packaged with a single capsid Y444FVP3 was 53% with a mean of 10,103 ± 6,461 GFP-positive cells to 18,929 ± 7,430 Thy 1.2–positive RGCs/mm2. Differences between NDI1- and GFP-transduced cells were statistically significant (P < 0.0005) (Figure 1p). One month after scAAV injections, immunoblotting of the infected retina confirmed the expression of NDI1 in mitochondrial extracts of NDI1-injected eyes, but not in GFP-injected eyes (Figure 1q). NDI1 immunoreactivity was absent in the cytoplasmic fraction, thus NDI1 was efficiently transported into the mitochondria. RNA analysis revealed the presence of NDI1 transcripts in the retinas dissected from NDI1-injected eyes, but was absent in eyes injected with GFP (Figure 1r). Thus, NDI1 expressed in the target cell type, RGCs, whose axons comprise the optic nerve. Next, we examined the effects of NDI1 on EAE.

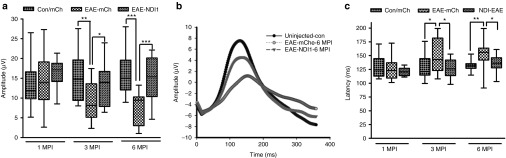

NDI1 preserves visual function in EAE

Using the pattern electroretinogram (PERG) as a sensitive measure of visual loss and RGC function, unsensitized mice that were vitreally injected with scAAV-mCherry (n = 10), EAE sensitized mice injected with scAAV-mCherry (n = 10) and mice sensitized for EAE and injected with scAAV-NDI1 (n = 10) were compared for progression of experimental optic neuritis. mCherry contained the 23 amino acid leader sequence of cytochrome oxidase subunit 8 (COX8) appended to the N terminus of the red fluorescent protein cherry for import into mitochondria. At 1 month after injection, there were no significant differences in median PERG amplitudes (Figure 2a). By 3 months and also at 6 months after injection, PERGs revealed a significant reduction in amplitude of the EAE-mCherry group compared with unsensitized controls injected with mCherry, 42% (P = 0.0035) and 51.7% (P = 0.0001) respectively. In contrast, NDI1-rescued mice showed slight 13% and 8% reductions in PERG amplitude that were not statistically significant. Thus, NDI1-rescued PERG amplitudes by 67% (P = 0.029) and 84% in EAE (P = 0.0002). Averaged PERG waveforms illustrate the loss in amplitude associated with EAE is suppressed by NDI1 (Figure 2b). Also, evident is the increase in PERG latency for the EAE-mCherry group by 15% (P = 0.049) and 16% (P = 0.0243) compared with mCherry unsensitized controls without EAE. NDI1 rescued this delay by 100% (P = 0.0134) and 77% (P = 0.0428) at 3 and 6 months after injection (Figure 2c). Mean PERG amplitudes ± SE at 1, 3, and 6 months after injection and the corresponding P values are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Latency values are shown in Supplementary Table S2. By all parameters examined, NDI1 preserved visual function. We next looked for the benefits of NDI1 on suppressing the hallmark loss of ganglion cells detected by optical coherence tomography (OCT) that results in permanent disability in MS.14

Figure 2.

Visual function. Pattern electroretinogram analysis of unsensitized controls vitreally injected with scAAV-cherry (Con/mCh), EAE mice vitreally injected with scAAV-mCherry (EAE-mCh) and EAE mice vitreally injected with scAAV-NDI1 (EAE-NDI1) were performed at 1 MPI (n = 18, 17, and 15, respectively), 3 MPI (n = 15, 16, and 15, respectively), and 6 MPI (n = 10, 16, and 15, respectively). (a) Box-whisker plots of PERG amplitudes, (b) averaged PERG waveforms, and (c) box-whisker plots for PERG latency are plotted. Number of repetitions = 3, for each group and time point, *P = 0.05-0.01; **P = 0.001–0.009; ***P = 0.0001–0.0009. EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; MPI, month(s) post injection; ms, milliseconds; PERG, pattern electroretinogram; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus.

NDI1 preserves the RGC and inner plexiform layer

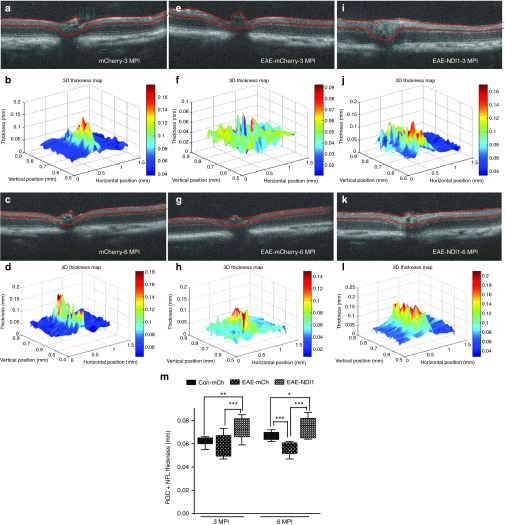

Serial high-resolution spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) imaging revealed thinning of the inner retina associated with the effects of EAE. Unsensitized controls vitreally injected with AAV-mCherry and examined at 3 and 6 months after injection revealed no losses of inner retinal structure (Figure 3a–d). As the RGC layer cannot be resolved in the mouse by OCT, we used the inner boundary of the RGC layer adjacent to the vitreous and the outer boundary of the inner plexiform layer (IPL) marked with red lines that were measured for thickness (Figure 3a,c). Three-dimensional retinal thickness maps were derived using MATLAB software (Figure 3b,d). The 25 cross sectional images derived from each OCT image were manually segmented and mean RGC + IPL thickness are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Relative to unsensitized controls the EAE-mCherry group showed progressive retinal thinning from 3 months (Figure 3e,f) to 6 months (Figure 3g,h) after AAV injection and EAE sensitization. For the EAE-NDI1–treated group, there was no decrease in thickness at 3 (Figure 3i,j) to 6 months (Figure 3k,l) after EAE sensitization and AAV injections. Plots of the OCT data revealed a 9% and 15% reduction at 3 and 6 months after injection respectively in EAE-mCherry compared with the unsensitized mCherry-control group, 3 months after injection (P = 0.089) and 6 months after injection (P = 0.0001) (Figure 3m). Although the EAE-mCherry group showed thinning, the EAE-NDI1 group showed a slight thickening at 3 and 6 months after injection by 16% and 11% respectively which was also statistically significant, P < 0.05 (Figure 3m). If NDI1 suppressed RGC injury, then axons of the optic nerve should not be lost in EAE.

Figure 3.

Serial in vivo optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging. Serial high-resolution spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) imaging was performed at 3 MPI of (a) unsensitized mCherry-injected controls with (b) three-dimensional (3D) thickness map, 6 months after injection in (c) 2D and (d) 3D (n = 11, no repetition). At 3 months, the inner retinal thinning (e) in the EAE-mCherry cross section and (f) in the 3D map are shown. By 6 months, worsening thinning on (g) cross sectional imaging and (h) 3D map are shown (n = 7, no repetition). The optic nerve head is seen on the (i) cross sectional image and (j) 3D map and at 6 months on the (k) retinal cross section and (l) 3D map (n = 17, no repetition). Box-whisker plots of the OCT data compared the groups at (m) 3 and 6 MPI. P < 0.05; *P = 0.05-0.01; **P = 0.001–0.009; ***P = 0.0001–0.0009. EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; MPI, month(s) post injection.

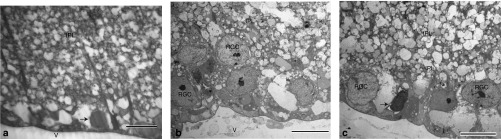

NDI1 rescues optic nerve axons from EAE-induced neurodegeneration

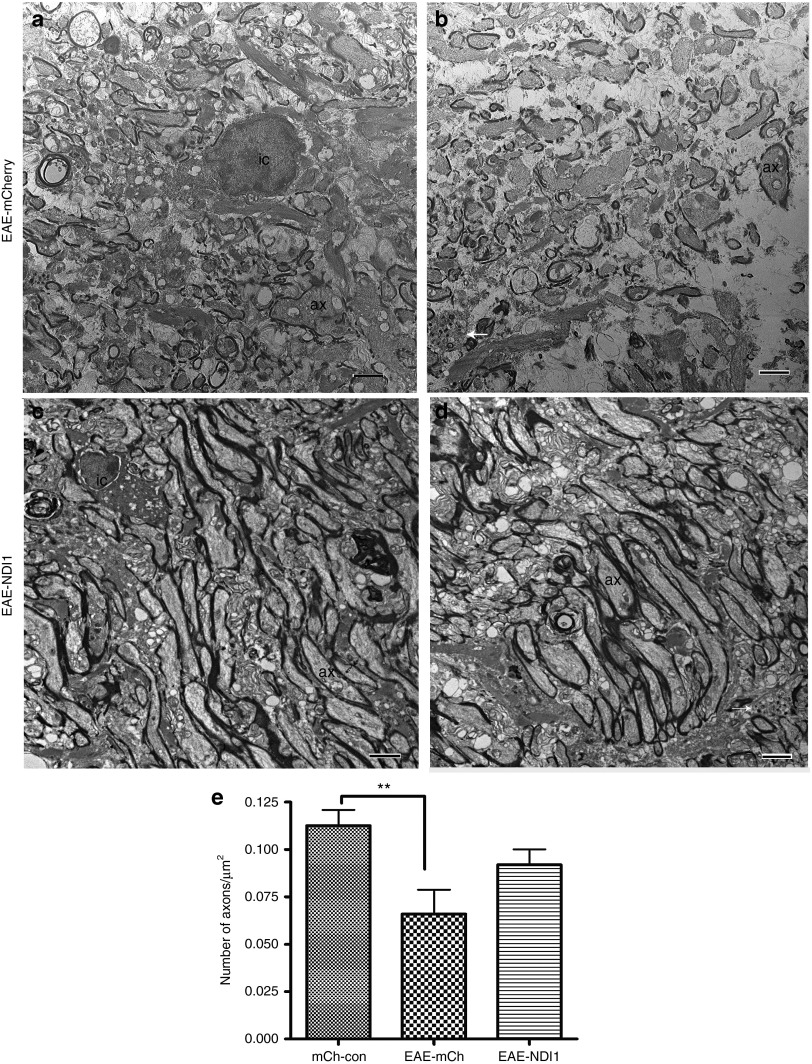

Optic nerves from animals euthanized 6 months after intravitreal injections were examined by light and transmission electron microscopy for axonal preservation with NDI1 treatment (n = 12) relative to the EAE-mCherry (n = 12) and unsensitized mCherry (n = 12) groups. Supplementary Figure S1a shows the normal optic nerve where myelination commences just posterior to the lamina scleralis and inflammatory cells are absent. Six months after sensitization for EAE, the characteristic cellular infiltration is evident in the mock-treated optic nerves (Supplementary Figure S1b). Relative to the normal optic nerve, the diameter with mock treatment of EAE is smaller. With AAV-NDI1 treatment, the cellular infiltration of EAE was evident (Supplementary Figure S1c), but the diameter of the optic nerve was larger than with mock treatment. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that in the EAE-mCherry animals, optic nerve axonal loss was a predominant finding along with inflammatory cells (Figure 4a). Remaining axons with thin or absent myelin lamellae contained electron dense aggregations characteristic of ongoing neurodegeneration (Figure 4b). Despite the presence of inflammatory cells, optic nerve axons in the EAE-NDI1–treated animals appeared to be relatively healthy and myelinated with an almost normal density of fibers (Figure 4c). Still some axons were degenerating, although most appeared to have no loss of neurotubules or hydropic degeneration of mitochondria (Figure 4d). The mean number of axons in the unsensitized control-mCherry group was 0.112 ± 0.008 (mean ± SE) per µm2, whereas for EAE-mCherry mice, the mean axon count was 0.065 ± 0.012 per µm2; thus, a 42% loss of optic nerve axons compared with the unsensitized control-mCherry group (P = 0.0058). Mean optic nerve axon counts for the EAE-NDI1–treated group was 0.091 ± 0.008 per µm2 that corresponded to a 19% loss of axons compared with unsensitized mCherry controls. However, this difference was not statistically significant and indicated that NDI1 suppressed axonal loss. When we compared the axonal count differences of EAE-mCherry mice with unsensitized controls versus the differences between NDI1 relative to unsensitized mCherry controls, comparisons were highly significant (P = 0.0004). Thus, NDI1 kept axonal density near-normal in the EAE optic nerve. Next, we looked for the mechanisms of this neuroprotective effect.

Figure 4.

Optic nerve ultrastructure. Six months after intravitreal AAV injections transmission electron microscopy shows (a) a mononuclear inflammatory cell (IC) and axonal loss in the EAE-mCherry optic nerve, with (b) an axon exhibiting electron dense aggregations characteristic of ongoing degeneration (arrow). With NDI1 treatment, (c) a mononuclear cell (IC) and (d) preservation of optic nerve axons (ax) are shown. (e) A bar plot of optic nerve axon counts is shown. n = 12 for each group, no repetition, **P = 0.0058. Scale bar = 2 µm. AAV, adenoassociated virus; Ax, axon; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; IC, inflammatory cell.

NADH-dehydrogenase activity is reduced in EAE

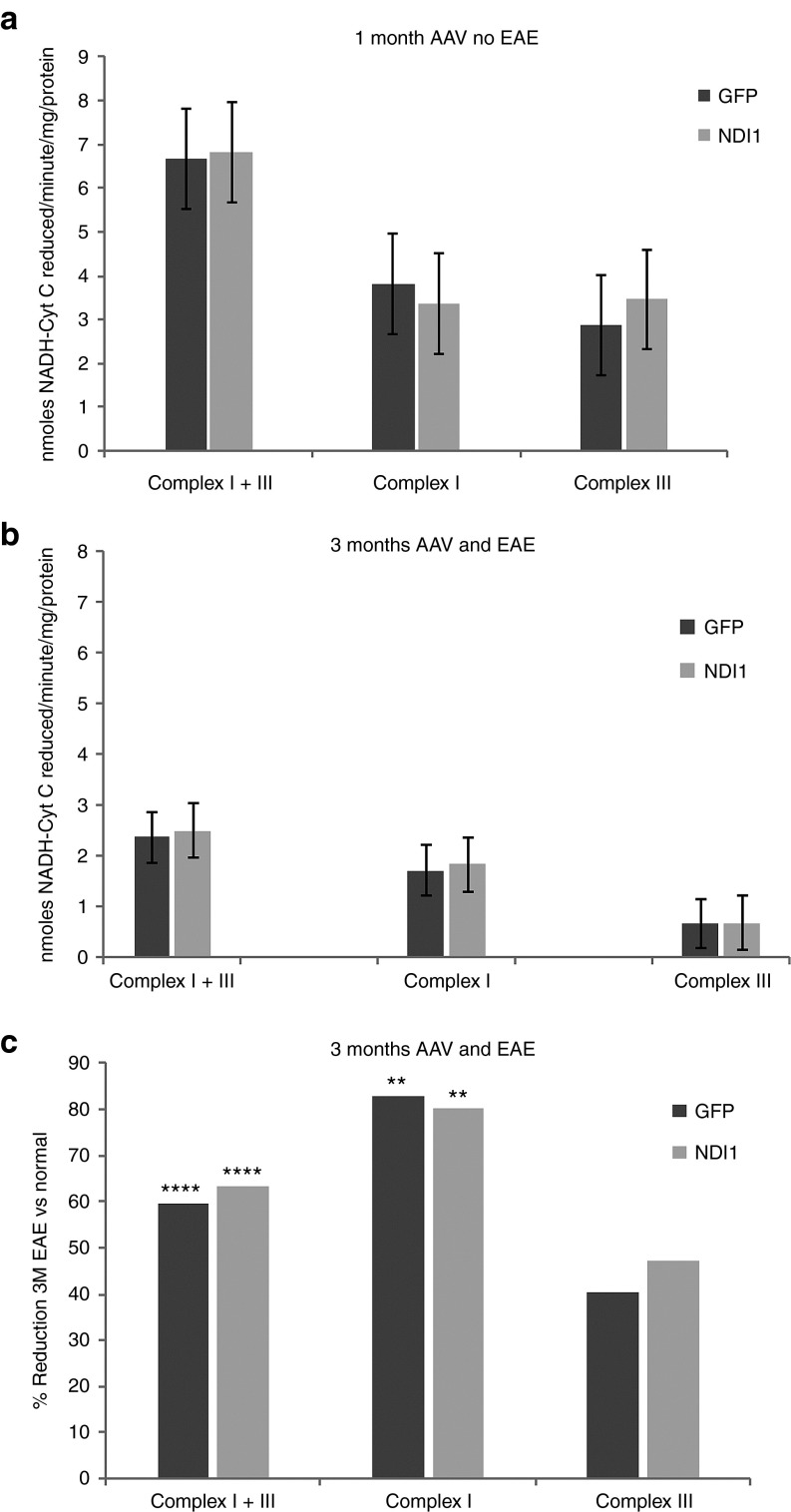

To determine whether NDI1 alters respiration in the normal optic nerve, we measured complex I + III activity 1 month after AAV injections. Here, we found no differences in complexes I or III activity between scAAV-NDI1– or scAAV-GFP–injected eyes in animals that were not sensitized for EAE. Mean complex I + III activity for the NDI1-injected nerves (n = 7) was 6.83 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg, whereas for GFP-injected optic nerves, (n = 7) it was 6.66 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg (Figure 5a). Mean complex I activity for the NDI1-injected optic nerves was 3.36 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein, whereas the activity for GFP-injected eyes were 3.8 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein. However, as NDI1 is rotenone insensitive, we did find an increase in the value obtained for complex III activity with a mean of 3.46 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein with NDI1 injection relative to 2.86 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein for GFP, but differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Respiration. (a) Complex I + III, complexes I or III activities were performed and plotted (n = 7 for each group, number of repetitions = 3). Three months after EAE sensitization and scAAV injections, complex I + III, complexes I and III activities were performed. (b) Values and (c) percent reductions of EAE relative to the 1 month control values are shown. n = 6, number of repetitions = 3. ****P < 0.001; **P < 0.007. EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus.

Next, we looked at complexes I and III activities in EAE with NDI1 treatment 3 months after intravitreal injections and antigenic sensitization. Here, we found complex I activity was reduced by the effects of EAE, but that it was unaltered by infection with scAAV-NDI1. Mean values for complex I activity for NDI1 infected nerves was 1.83 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein (Figure 5b), an 80% drop relative to the 1 month after injection values of unsensitized mice, P = 0.00687 (Figure 5c). Similarly, mean complex I activity for GFP-infected control nerves was 1.71 nmoles NADH reduced/minute/mg protein, representing an 83% drop relative to the 1 month after injection values of unsensitized animals. All values for complex III activities were reduced ~40%, differences between 1 month and 3 month values were not statistically significant. Although complex I activity was severely impacted by the effects of EAE, NDI1 did not improve respiration in the EAE optic nerve. Next, we looked for alternative mechanisms of neuroprotection by NDI1.

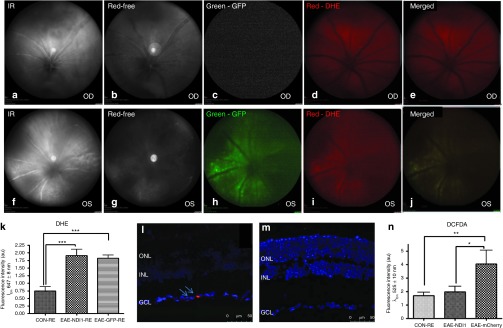

NDI1 suppresses oxidative stress induced by EAE

As NDI1 transfers electrons from flavin adenine dinucleotide to ubiquinone without proton pumping and it lacks the iron-sulfur cluster of the 45 subunit vertebrae complex I that generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria, we tested whether NDI1 reduced oxidative stress using a fluorescent probe dihydroethidium (DHE) to detect intracellular superoxide in live mice. Superoxide oxidizes DHE to a red fluorescent signal. For these experiments, unsensitized controls (n = 5) and EAE mice (n = 10) received intravitreal scAAV-NDI1 injected into the right eyes and scAAV-GFP injected into the left eyes. Two weeks after AAV injections and antigenic sensitization for EAE, DHE was injected intravitreally into both eyes. One hour later, the eyes were imaged using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (CSLO) that visualized the optic nerve head and the retinal nerve fiber layer. Right eyes (Figure 6a,b) treated with scAAV-NDI1 showed no fluorescence with the green barrier filter (Figure 6c), whereas DHE-induced fluorescence was evident in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer with the red barrier filter (Figure 6d) and with the red and green filters merged (Figure 6e). Similarly, CSLO imaging of the left eye mock treated with scAAV-GFP (Figure 6f,g) revealed GFP-positive RGCs and nerve fibers (Figure 6h) that were positive for superoxide (Figure 6i) and merged (Figure 6j).

Figure 6.

Oxidative stress. One hour after intravitreal injection of DHE, CSLO images were performed of the optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer of the right eyes (a, infrared) and (b, red-free) treated with (c) NDI1 (green barrier filter), (d) DHE-induced fluorescence (red barrier filter) and with the (e) red and green filters merged. CSLO imaging of the left eye injected with (f) scAAV-GFP (infrared), (g) red-free, (h) GFP (green), (i) superoxide (red), and (j) merged. One day after imaging, a bar plot of retinal flat mount fluorescent intensity of superoxide levels in (k) EAE mice injected with scAAV-GFP or scAAV-NDI1 relative to retinas of unsensitized controls injected with scAAV-GFP is plotted. (l) Confocal microscopy of longitudinally sectioned retinas has superoxide (red) (arrows) in scAAV-GFP–injected eyes. (m) The signal (red) with NDI1 treatment is shown. (n) A bar plot of fluorescence intensities of CM-H2DCFDA–stained retinas is shown. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.005; *P = 0.01. n = 10 for each group, no repetition. CSLO, confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope; DHE, dihydroethidium; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; GCL, ganglion cell layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus.

We also detected in vivo hydrogen peroxide using the probe (5-(and-6)-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA). It has no fluorescence until it passively diffuses into cells, where intracellular esterase cleaves the acetates and the oxidation of CM-H2DCFDA by hydrogen peroxide produces a green fluorescent signal. Control (n = 5) and EAE mice (n = 10) received scAAV-NDI1 injected into the right eyes and scAAV-mCherry into the left eyes. One day after imaging, mice were euthanized and retinal flat mount fluorescence quantitated using a fluorescence spectrophotometer that revealed superoxide levels were elevated in EAE retinas relative to unsensitized controls injected with scAAV-GFP, P = 0.001 and also in NDI1-treated retina, P = 0.004 (Figure 6k). Confocal microscopy of longitudinally sectioned retinas showed the red DHE signal produced by superoxide within ganglion cells of AAV-GFP–injected eyes (Figure 6l), whereas the signal was not as evident with NDI1 treatment (Figure 6m). Fluorescence intensities of CM-H2DCFDA–stained retinas revealed that hydrogen peroxide levels were substantially elevated in EAE relative to unsensitized controls injected with scAAV-mCherry, P = 0.038 (Figure 6n). With NDI1 treatment hydrogen peroxide levels were significantly reduced relative to EAE mice injected with scAAV-mCherry, P = 0.01 (Figure 6n). In contrast, no differences were detected between unsensitized controls and EAE mice treated with NDI1. Clearly, NDI1 suppressed ROS activity. As oxidative stress is linked to loss of RGCs, we examined apoptosis next.

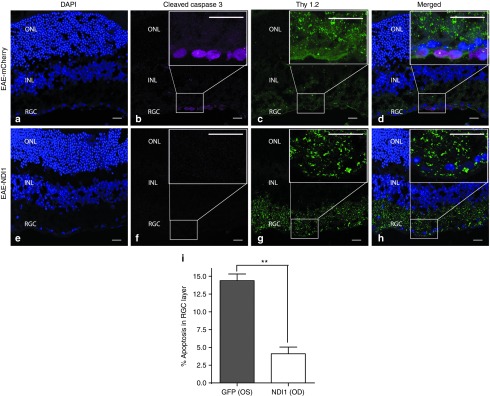

NDI1 rescues RGC apoptosis induced by EAE

Using analysis of cleaved caspase 3 immunofluorescence in longitudinal sections of the retina obtained from mice sensitized for EAE 6 months earlier, in eyes mock treated with scAAV-mCherry or rescued with scAAV-NDI1, we found DAPI in all three nuclear layers (Figure 7a), but cleaved caspase 3 was seen in the ganglion cell layer (Figure 7b). These apoptotic cells were labeled by Thy 1.2 (Figure 7c) indicating they were RGCs (Figure 7d). The sections obtained from the NDI1-rescued mice showed DAPI-stained nuclei in all the retinal layers (Figure 7e), but cleaved caspase 3 labeling was minimal (Figure 7f) in Thy 1.2 (Figure 7g)–labeled RGCs (Figure 7h). The TUNEL assay showed that the percentage of TUNEL-labeled cells to that of total DAPI-labeled cells in the RGC layer of GFP-injected eyes was 14.3% compared with 4% in NDI1-rescued eyes, P = 0.02 (Figure 7i). Thus, NDI1 reduced apoptosis by 71%.

Figure 7.

Apoptosis. Immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase 3 and Thy 1.2 in longitudinal retinal cryosections of mice sensitized for EAE 6 months earlier whose eyes were injected with scAAV-mCherry and stained for (a) DAPI. (b) Cleaved caspase 3 is shown in the ganglion cell layer where (c) Thy 1.2 colocalized with (d) apoptotic RGCs. The insets show higher magnification of the boxed RGCs. The retina from NDI1-rescued mice with (e) DAPI, but no (f) cleaved caspase 3 in (g) Thy 1.2–labeled (h) RGCs. (i) A bar plot shows the percentage of TUNEL-labeled cells to DAPI-labeled cells in the RGC layer of GFP-injected eyes versus NDI1-rescued eyes. Error bars represent standard error. n = 3 for each group, number of repetitions = 3. **P = 0.001. Scale bars = 25 µm. EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; RGC, retinal ganglion cell layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, left eye control; OD, right eye rescued; INL, inner nuclear layer; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus.

Transmission electron micrographs of the retinas from EAE animals injected with scAAV-mCherry revealed condensation of nuclear chromatin and loss of RGCs (Figure 8a). In contrast, EAE animals treated with scAAV-NDI1 had more RGCs with the characteristic elliptical and lighter nucleus (Figure 8b). Still, some apoptotic cells were present (Figure 8c). The NDI1-treated eyes of EAE mice had increased cystic spaces in the IPL relative to unsensitized animals injected with mCherry, thus perhaps accounting for the live OCT measures of increased RGC + IPL thickness in NDI1-treated EAE mice relative to the unsensitized mCherry controls. Clearly, NDI1 suppressed RGC loss in EAE.

Figure 8.

RGC ultrastructure. (a) Transmission electron microscopy performed on the retinas of EAE animals injected with scAAV-cherry show condensation of nuclear chromatin (arrow) and loss of cells in the RGC layer. (b) EAE animals treated with scAAV-NDI1 with RGCs with the characteristic elliptical and lighter nucleus are shown. (c) With NDI1 an apoptotic cell is shown (arrow) adjacent to normal appearing RGCs. The IPL of NDI1-treated eyes of EAE mice with increased cystic spaces is shown. Scale bar = 10 µm. n = 12 for each group, no repetition. EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; IPL, inner plexiform layer; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; scAAV, self-complementary adenoassociated virus; V, vitreous.

Discussion

Mitochondrial dysfunction mediates neurodegeneration that contributes to permanent loss of function in optic neuritis and MS.6,7 This dreaded sequelae has no remedy and is believed to be irreversible. Our work here clearly demonstrates that expression of NDI1 in mitochondria of RGCs of the EAE retina preserves vision, prevents oxidative injury, neuronal apoptosis, and demise of axons comprising the optic nerve for almost half the lifespan of the laboratory mouse. This study supports the work of Dutta and coworkers who first implicated mitochondria as a cause of neurodegeneration in MS.6 They found that complexes I and III activities were reduced by approximately half in autopsied MS brains, and here, we found similar reductions in EAE. During that same year, mitochondrial involvement in the EAE animal model of MS was first described by Qi and associates.9 They found that the rate of ATP production was reduced even more than that observed in some diseases caused by inherited mutations in complex I subunit genes encoded by the mitochondrial genome. The surprise there was that loss of respiration occurred before the infiltration of inflammatory cells classically believed to mediate axonal loss by transection.15 Our study now supports that deficits in respiration in EAE are mostly due to complex I dysfunction. Last year, Campbell and associates found large kilobase deletions in the mitochondrial genome of neurons microdissected from autopsied MS brains.10 These deletions of mitochondrial DNA from nucleotide position 6,468 to 15,600 encompassed complex I subunits ND3, ND4L, ND4, and ND5 of the heavy strand and ND6 of the light strand. That complex I activity was impaired in MS lesions was further supported by Lu et al.16 and Witte et al.17 Kumleh and coworkers found reduced complex I in MS, but that this deficit was not due to deletions in mtDNA.18 Bosley et al. linked nonsynonymous single nucleotide changes in ND1, ND2, ND4, and ND5 of leukocytes from patients with optic neuritis to poor recovery of vision.19 Clearly, the link between mitochondria and disability caused by neurodegenerative in MS is gaining substantial momentum.7

Still, tackling the consequences of mutated mtDNA to thwart this sequelae in MS is difficult, as treatments for disorders caused by mutated mtDNA are inadequate.7 Many experimental techniques have been proposed to address disorders caused by mutated mtDNA and some could be applied to neuroprotection in MS. They include mitochondrial gene replacement in embryonic stem cells,20 RNA transfer,21 or DNA transfer,22 or changing the ratio of heteroplasmy with specific restriction endonucleases.23 Seo et al. used the NDI1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to rescue the respiratory deficiency of complex I deficient cell lines.24 The NDI1 gene is a single subunit NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase that appears to perform the function of the 45 subunit mammalian complex I. NDI1 is encoded in the nuclear genome, expressed on cytoplasmic ribosomes, and successfully transported into the mitochondrial inner membrane by an N-terminus mitochondrial targeting sequence. The Yagi laboratory has applied their NDI1 technology to alleviating the consequences of a human cell line carrying a homoplasmic frame shift mutation in the ND4 gene.25 Recently, they used an AAV-expressing NDI1 to rescue the complex I deficiency induced by rotenone in the rodent visual system.26 Gene therapy with NDI1 does not appear to cause inflammation in rodents27 and has the advantage whereby a single construct, NDI1, can treat disorders caused by deletions or mutations in multiple subunits of the 45 subunit vertebrae complex I.26

NDI1 has been extensively studied as a potential treatment for mitochondrial diseases,26,28 but not in EAE where we proved it is neuroprotective. Expression of NDI1 in mitochondria of cultured cells,25 flies,29 nematodes,30 or rodents26 has been found to be functionally active with restoration of complex I activity thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis and neuroprotection. As we showed here, the mechanism of benefit may not be due to improvements in oxidative phosphorylation, but rather by decreasing oxidative stress.29,31 Recent work suggests that erythropoetin may be protective against the RGC loss associated with optic neuritis.32 However, the newly approved oral MS drug fingolimod is not effective against RGC loss in EAE,33 but NDI1 is.

For human gene therapy, an effective and safe delivery system is essential. This can be achieved by using AAV vectors. The AAV virus is a small, single-stranded DNA-containing nonpathogenic virus belonging to the Dependovirus genus of the Parvoviridae family.34,35 Recombinant AAV vectors have been safely used in clinical trials for a number of ocular and non-ocular diseases such as Leber's congenital amaurosis,36 hemophilia B,37 cystic fibrosis,38 α-1 antitrypsin deficiency,39 Parkinson's disease,40 Batten's disease,41 and muscular dystrophy.42 There has been extensive research on these viral vectors, with much advancement, particularly in the area of vector serotypes, transduction efficiency, stability, tropism, and most importantly safety. The RGC layer exclusively affected in optic neuritis can be targeted by optimizing the vector serotype, AAV2, and by choosing the route of vector administration, intravitreal injection. Self-complementary vectors used here for gene delivery of NDI1 that contain both positive and negative strands43 and tyrosine to phenylalanine mutations in the capsid proteins also used in our study increase the speed and efficiency of transgene expression, crucial to intervention in optic neuritis with its characteristic rapid onset of permanent visual loss.44

The entire CNS can potentially be targeted for neuroprotection by changing the AAV serotype to type 9. AAV9 gives excellent transgene expression in the brain and spinal cord following intravenous administration45 that may be even more robust with the disruption of the blood–brain barrier characteristic of EAE and MS.46

We focused on the optic nerve for several reasons. It is a readily accessible site for gene therapy, particularly with the AAV2 vector that has a tropism for RGCs. Lesions in the optic nerve directly correlate to function, where mitochondrial density in the optic nerve is higher than other CNS tracts,47 thus making it more susceptible to mitochondrial perturbations. RGC loss can be gauged serially by OCT in patients with MS and optic neuritis.48 Taken together with the high incidence of optic nerve involvement in MS and EAE, we believe the optic nerve to be an ideal CNS tract for testing the effects of treatments designed to suppress mitochondrial and tissue injury and ameliorate disability.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the viral vectors. The cDNA of yeast NDI1 (a kind gift from Professor Yagi) was cloned into ssAAV plasmid vector pTR-UF22 and regulated by the 381-bp cytomegalovirus immediate early gene enhancer/1352-bp chicken β-actin promoter-exon 1–intron 1 woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element that were digested with the restriction enzymes EcoR1, BglII, and Eag1. The 1852 base pair fragment carrying the EcoR1 overhang at the 5′ end and the Bgl II overhang at the 3′ end of NDI1 were gel purified. Similarly, the parent sc-trs-SB-hGFP vector was digested with XhoI and BamH1 to remove the hGFPcDNA that was replaced with the 1852 bp fragment containing NDI1 cDNA. The BamH1 and BglII overhangs were compatible and were ligated, whereas EcoR1 and XhoI were not compatible and were end filled to make the ends blunt and were further ligated using T4 DNA ligase. The clones were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing, then packaged into AAV2 vectors. NDI1 cloned into scAAV2 was regulated by a short hybrid cytomegalovirus immediate early gene enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter.

We packaged self-complementary AAV vectors with a single tyrosine (Y) to phenylalanine (F) mutation at position 444 in the VP3 capsid (Y444F) or triple Y-F mutations at positions 444, 500, and 730 (Y444F+Y500F+Y730F) in the VP3 capsid for delivery of NDI1, COX8cherry (mCherry), or GFP.49 The scAAV2-NDI1-triple Y-F capsid mutant (Y444F+Y500F+Y730F) or a control scAAV2-GFP with or without Y444F capsid mutations or scAAV-mCherry that contained the 23 amino acid leader sequence of cytochrome oxidase subunit 8 (COX8) appended to the N terminus of the red fluorescent protein cherry were produced by the plasmid cotransfection method.50 The plasmids were amplified and purified by means of cesium chloride gradient centrifugation and then packaged into AAV2 capsids by transfection into human embryonic kidney 293 cells using standard procedures. In brief, the crude iodixanol fractions were purified using a fast protein liquid chromatography system (AKTA; Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), the vector was then eluted from the column using 215 mmol/l sodium chloride (pH, 8.0), and the rAAV peak was collected. Vector-containing fractions were then concentrated and buffer exchanged in balanced salt solution (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) with 0.014% polysorbate 20 (Tween20; Jiangsu Haian Petrochemical Plant, Jiangsu, China), using a centrifugation concentrator (Biomax 100 K; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Vector was then tittered for DNase-resistant vector genomes by real-time PCR relative to a standard,50 scAAV-GFP mutant 444 (1.03 × 1012 vg/ml), scAAV-NDI1 triple mutant (4.34 × 1012 vg/ml), and scAAV-mCherry (8.66 × 1012 vg/ml). Finally, the purity of the vector was validated by silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, assayed for sterility and lack of endotoxin, then divided into aliquots and stored at −80 °C.

Intraocular injections. For the intraocular injection of recombinant AAV, DBA/1J mice were sedated by inhalation with 1.5–2% isoflurane. A local anesthetic (proparacaine hydrochloride) was applied topically to the cornea and pupils were dilated by applying a drop of tropicamide. A 32-gauge needle attached to a Hamilton syringe was inserted through the pars plana under the dissecting microscope. One microliter of scAAV2-NDI1 packaged with triple mutant VP3 (4.34 × 1012 vg/ml) (n = 10) was injected into one eye and scAAV-GFP (1.86 × 1012) was injected in the contralateral eye as an internal control.

Flat mounts, cryosections, and immunolabeling. One week after the viral injections mice were euthanized. The globes and optic nerves were dissected out. Eyes (n = 7) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution for 1 hour and were then transferred to 0.4% paraformaldehyde overnight. To make flat mounts, the cornea and crystalline lens were removed, and the entire retina was carefully dissected from the eyecup. Four radial cuts were made from the edge to the equator of the retina to make it flat. After 3 washes in PBS, retinas were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Dow Chemical, Midland, MI) in PBS for 1 hour then blocked with 0.5% Triton X-100 containing 10% goat serum for 1 hour. Flat-mounted retinas were then rinsed in PBS and incubated with a mixture of rabbit polyclonal anti-NDI1 (1:100) antibody (a kind gift from Professor Yagi) or polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:100) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) along with mouse monoclonal NDUFB6 (1:100) (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR) and monoclonal rat Thy 1.2 (1:200) (Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After 3 washes with PBS, the retinas were treated with the secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit Cy2 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), goat anti-mouse Cy5 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), goat anti-rat Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), along with 4″,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (2 µg/ml) (DAPI) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), in 1:500 dilution, incubated at 4 °C overnight. All the primary and secondary antibodies were reconstituted in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH, 7.4) containing 10% goat serum. The retinal tissues were finally washed three times in PBS. The whole mounts were then placed on glass slides (RGC layer facing up), cover slipped, and observed for fluorescence with a confocal microscope (Leica TCSSP5; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For cryosections, the retinas were embedded in optimal cutting temperature embedding compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) at −80 °C overnight. Retinal sections, 8 µm in thickness, were cut then mounted on glass slides with fluorescent mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) then examined for fluorescence using a Leica confocal microscope. The NDI1 positive, Thy 1.2 immunopositive RGCs in the right eye and GFP positive, Thy 1.2 immunopositive RGCs in the left eye were counted on longitudinal sections of the retina. The total cell counts were an average of the counting data from 11 different regions of the retina and expressed per mm2 area. The images were captured on the confocal microscope with a 63X oil objective for counting the cells.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase PCR. Retinas and optic nerves from the left (GFP) and right (NDI1) eye were dissected out (n = 3) 1 month after injection and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD). RNA concentration was measured with a spectrophotometer, and 500 ng of RNA was used to reverse transcribe into cDNA (iScript; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). cDNAs were further amplified using gene specific primers and 18SrRNA was used as house keeping control. The following primers were used: NDI1 F-5′-GGTGGGCCTACTGGTGTAGA-3′, NDI1 R-5′-CAATGGCGAAAATGTTGTTG-3′ with expected PCR product size of 134 base pairs; 18SrRNA F-5′-GAACTGAGGCCATGATTAAGAG-3′, 18SrRNA F-5′-CATTCTTGGCAAATGCTTTC-3′ with expected PCR product size of 120 bp. Resultant PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel.

Western blotting. The retina and optic nerves were dissected out from the mice injected 1 month earlier with NDI1 (OD) or GFP (OS), mitochondria and cytoplasm were isolated and were quantified using the Bio-Rad Dc protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amount of protein (15 µg) was loaded on the 4–12% NuPageBis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and were electro-transferred onto the PVDF membrane. For immunodetection, the membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal to NDI1, rabbit polyclonal to GFP (Abcam), mouse monoclonal to β-actin antibodies (Abcam). The goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used and were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Complex I + III activity assay. Optic nerves from NDI1-injected right (n = 7) and GFP-injected left (n = 7) eyes were homogenized in mitochondrial isolation buffer and the cells disrupted using three freeze thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. NADH-cytochrome oxidoreductase activity was assayed in 0.1 mol/l potassium phosphate pH 7.5, 2 mmol/l NADH, 10 mmol/l KCN, 1 mmol/l oxidized cytochrome C at 30 °C using 1.5 µg of protein from each tissue. NADH oxidoreductase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 550 nm for 2 minutes and the sensitivity for rotenone tested by adding 10 µl of 1 mmol/l rotenone. The slope of the run was recorded and the activity expressed in nanomoles of NADH-cytochrome C reduced per minute per µg of protein.

Induction of EAE. EAE was induced in female DBA/1J mice (n = 20) by sensitization with 0.1 ml of sonicated homologous spinal cord emulsion in complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and injected subdermally into the nuchal area. Control animals (n = 10) received subdermal inoculation with Freunds adjuvant. Ten out of 20 mice sensitized for EAE were rescued with the intravitreal injection of scAAV-NDI1 triple mutant (4.34 × 1012 vg/ml) into both eyes, 10 EAE sensitized mice received 1 µl of scAAV-mCherry (8.66 × 1012 vg/ml) into both eyes served as controls. Normal unsensitized animals received 1 µl of scAAV-mCherry as additional controls. Serial PERGs for RGC function and OCT for retinal thickness measurements were evaluated at 1, 3, and 6 months, then mice were humanely euthanized. The excised retinas and optic nerves were processed for histological and ultrastructural analysis.

PERG. Pattern ERGs were obtained for all three groups: unsensitized mCherry (n = 10), EAE-mCherry (n = 10) and EAE-NDI1 (n = 10) mice at 1, 3, and 6 months. Mice were weighed then anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg). Anesthetized mice were gently restrained with a bite bar and a nose holder. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C using a feedback controlled heating pad. The eyes of the anesthetized mice were wide open and steady, with undilated pupils pointing laterally and upward. The ERG electrode (0.25-mm diameter silver wire configured to a semicircular loop of 2-mm radius) was placed on the corneal surface and positioned to encircle the pupil without limiting the field of view. Reference and ground electrodes made of stainless steel needles were inserted under the skin of the scalp and tail, respectively. A drop of balanced saline was topically applied to the cornea to prevent drying during recordings. A visual stimulus of contrast-reversing bars (field area, 50° × 58° mean luminance, 50 cd/m2; spatial frequency, 0.05 cyc/deg; contrast, 100%; temporal frequency, 1 Hz) was aligned with the projection of the pupil at a distance of 20 cm. Retinal signals were amplified by 10,000-fold and band-pass filtered by 1–30 Hz. Three consecutive responses to each of the 600 contrast reversals were checked for consistency by superimposition and were averaged, then analyzed to evaluate the major positive and negative waves using commercially available software (Sigma Plot; Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test for paired data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

SD-OCT imaging. High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of the retina was performed on live mice using SD-OCT (Bioptigen, Durham, NC). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) and pupils were dilated using a drop of tropicamide (1%). Systane Ultra (Alcon Laboratories) lubricating eye drops were applied to the cornea to preserve corneal hydration and clarity. Mice were secured on a custom stage, which allowed free rotation, to align the eye for imaging of the optic nerve head. Rectangular volume scans centered on the optic nerve head were acquired in both eyes. For analysis of SD-OCT images, 25 images around the optic nerve head were checked from each eye to ensure consistent image quality across the scan. The eyes with images showing shadowing due to the media opacities were excluded from the analysis. Using algorithms in MATLAB software, we drew boundaries and measured the distance from the RGC layer to the inner boundary of the inner nuclear layer for 25 images of each eye. The segmented image information was used to construct three-dimensional geometric plots of retina using algorithms for three-dimensional thickness maps in MATLAB. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test for unpaired data, P < 0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance.

Oxidative stress. The probe (5-(and-6)-2′,7′-CM-H2DCFDA was used to detect hydrogen peroxide. CM-H2DCFDA has no fluorescence until it passively diffuses into cells, where intracellular esterase cleaves the acetates and the oxidation of CM-H2DCFDA by hydrogen peroxide produces a green fluorescent signal. For CM-H2DCFDA experiments, control (n = 5) and EAE mice (n = 10) received 1 µl of intravitreal scAAV-NDI1 injected into the right eyes and scAAV-mCherry into the left eyes.

The probe DHE was used to detect intracellular superoxide. Superoxide oxidizes DHE to a red fluorescent signal. For DHE staining experiments, control (n = 5) and EAE (n = 10) mice received intravitreal scAAV-NDI1 injected into the right eyes and scAAV2-GFP into the left eyes. Meanwhile, 5 mmol/l stock solutions of CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen; cat#C6827) was prepared in anhydrous DMSO, whereas 5 mmol/l stock solution of DHE was purchased from Invitrogen (cat#D23107). The stock solution of CM-H2DCFDA and working concentrations of 500 µmol/l solutions were prepared fresh in sterile PBS just before intraocular injections into live mice.

Two weeks after EAE sensitization and intraocular AAV injections mice were anesthetized, the pupils dilated, then 1 µl of CM-H2DCFDA or DHE was injected intravitreally into the respective mice, which makes the final concentration of the probe to 100 µmol/l and the DMSO to ~1% in the mouse eye, assuming the vitreous volume of the mice to be ~5.3 µl. One hour after injections, eyes were imaged using a CSLO (Heidelberg Engineering, Bonn, Germany). The built-in 488 laser was used for the excitation of both CM-H2DCFDA and DHE and band-pass filters of 500–550 were used for detection of the CM-H2DCFDA emission and LWP542 (542–800 nm) was used for the DHE emission. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, pupils were dilated with phenylephrine/atropine and corneal hydration was maintained with balanced salt solution. Retinal images were obtained using a 30° field of view and real time averaging of 50 images. The CSLO was focused on the inner retina by imaging of the nerve fiber layer at 488 nm through the CSLO polarization filter (red-free imaging).

One day after imaging, mice were euthanized and eyes excised then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour. Retinas were then dissected out and transferred to a 96-well Microfluor 2 black, flat bottom microtiter plate (Thermo, Milford, MA) containing 100 µl PBS and fluorescence was measured using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian, Cary, NC). The fluorescence intensities of the CM-H2DCFDA–stained retinas were measured using a 488 nm excitation and 500–600 nmol/l emission, whereas for DHE, the excitation wavelength was 350 nm and the emission scan was performed from 450–750 nm. The peak emission for DCFDA at 525 ± 10 nmol/l from all the retinas and optic nerves was averaged and plotted. The DHE peak emissions at 647 ± 8 nmol/l from all the DHE-stained retina/optic nerves were averaged. Student's t-test was used to test for significant differences between the groups. Tissues were also processed for cryomicroscopy, then observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) or confocal microscope.

Apoptosis. DNA fragmentation characteristic of apoptosis in retinal whole mounts was monitored by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated UTP end labeling, TUNEL) staining using the ApopTag Red In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mice sensitized for EAE (n = 3) and rescued with OD (NDI1), OS (GFP) at the same time were killed after 3 months after injection and the eyes were enucleated, fixed overnight in 1% paraformaldehyde. The anterior segment, the lens, the vitreous body were removed. The retina was gently separated from the globe with a fine forceps under an optical microscope and four radial cuts were made to flatten the retina. The retinal whole mounts were postfixed in chilled (−20 °C) ethanol/acetic acid 2:1 (vol/vol) for 5 minutes, and rinsed twice with PBS. The retinas were then transferred to a 96-well plate, incubated with terminal deoxynucleatidyl transferase and digoxigenin-dUTP and stained with rhodamine-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody as per the manufacturer's instructions. The retinas were washed with PBS three times (2 minutes each) and were counter stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (2 μg/ml) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), in 1:500 dilution in PBS for 1 hour. The retinas were washed three times with PBS and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature embedding compound (Sakura Finetek). Retinal sections 8 μm thick were cut and mounted on glass slides with fluorescent mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories) and examined for fluorescence using a confocal microscope (Leica TCSSP5; Leica). The percentage difference of apoptotic cells in the RGC layer of right (NDI1) and left (GFP) eyes was determined by counting the number of cells in randomly selected microscope fields with nuclei exhibiting red fluorescence (rhodamine), indicative of DNA fragmentation. Apoptosis of RGCs was further confirmed on cryosections of the retina obtained from the mice sensitized for EAE and injected with mCherry or rescued with NDI1 using cleaved caspase 3 and Thy 1.2 immunostaining. Briefly, the sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour, blocked with 10% goat serum in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour and incubated with the rabbit monoclonal to cleaved caspase 3 (1:100) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and rat monoclonal to Thy 1.2 (1:100) (Abcam) antibodies. The sections were washed three times 5 minutes each with PBS and incubated with goat anti-rabbit Cy5 (1:500) and goat anti-rat Cy2 (1:500) (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). The sections were counter stained with DAPI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 2 µg/ml) for 10 minutes washed with PBS three times 5 minutes each, mounted with fluorescence media (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories) and observed under a confocal microscope (Leica TCSSP5; Leica).

Histopathology. Mice were euthanized 6 months after EAE sensitization and AAV injections by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (0.3 mg/g body weight). They were then perfused by cardiac puncture with fixative consisting of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/l PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The eyes with attached optic nerves were dissected out and the retinas and optic nerves were separated. The specimens were further processed by immersion fixation in 2.5% gluteraldehyde, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, 0.1 mol/l sodium cacodylate-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 7% sucrose in the cold, and then dehydrated through an ethanol series to propylene oxide, infiltrated, and embedded in epoxy resin that was polymerized at 60 °C overnight. Semi-thin longitudinal sections (0.5 μm) of the optic nerve and retina were obtained and stained with toluidine blue for light microscopic examination. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were also obtained from all the mice and were placed on nickel grids for transmission electron microscopic examination.

Optic nerve specimens were examined using a Hitachi H-7000 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 80 kV. For axon counts, five micrographs were photographed at low magnification (2,500×) for each optic nerve specimen. The number of axons was then manually counted by an observer masked to the treatment agent.

Biostatistics. Comparisons of PERG, OCT, TUNEL, ROS, and axon numbers between the groups were analyzed by Student's t-test with P < 0.05 considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Light microscopy of optic neuritis. Table S1. Mean PERG amplitudes recorded at 1, 3, and 6 months post rAAV injection for the mCherry, EAE-mCherry and EAE-NDI1 groups. Table S2. Mean PERG latencies at 1, 3, and 6 months post rAAV injection for the mCherry, EAE-mCherry and EAE-NDI1 groups. Table S3. Average retinal thickness (mm) (RGC + IPL) derived using MATLAB software of mCherry, EAE-mCherry and EAE-NDI1 OCT images taken at 1, 3, and 6 months post rAAV injection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mabel Wilson for editing and Sacide Ozdemir for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants R01EY07892 and EY017141 (J.G.), EY EY021721 (W.W.H.), core grant P30-EY014801 and an unrestricted grant to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness. W.W.H and the University of Florida have a financial interest in the use of AAV therapies, and own equity in a company (AGTC) that might, in the future, commercialize some aspects of this work. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Guy J. Optic nerve degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ophthalmic Res. 2008;40:212–216. doi: 10.1159/000119879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjartmar C, Trapp BD. Axonal and neuronal degeneration in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and functional consequences. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14:271–278. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirani A, Zhao Y, Karim ME, Evans C, Kingwell E, van der Kop ML, et al. Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2012;308:247–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikic I, Merkler D, Sorbara C, Brinkoetter M, Kreutzfeldt M, Bareyre FM, et al. A reversible form of axon damage in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nm.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stys PK. General mechanisms of axonal damage and its prevention. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, McDonough J, Yin X, Peterson J, Chang A, Torres T, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:478–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Horssen J, Witte ME, Ciccarelli O. The role of mitochondria in axonal degeneration and tissue repair in MS. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1058–1067. doi: 10.1177/1352458512452924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman B. Role of mitochondria in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:244–252. doi: 10.1007/s11910-006-0012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Lewin AS, Sun L, Hauswirth WW, Guy J. Mitochondrial protein nitration primes neurodegeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31950–31962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GR, Ziabreva I, Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Reynolds R, Howell O, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletions and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:481–492. doi: 10.1002/ana.22109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koilkonda RD, Guy J. Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy-Gene Therapy: From Benchtop to Bedside. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:179412. doi: 10.1155/2011/179412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Lewin AS, Hauswirth WW, Guy J. Suppression of complex I gene expression induces optic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:198–205. doi: 10.1002/ana.10426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata M, Lee Y, Yamashita T, Yagi T, Iwata S, Cameron AD, et al. The structure of the yeast NADH dehydrogenase (Ndi1) reveals overlapping binding sites for water- and lipid-soluble substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15247–15252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210059109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trip SA, Schlottmann PG, Jones SJ, Altmann DR, Garway-Heath DF, Thompson AJ, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer axonal loss and visual dysfunction in optic neuritis. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:383–391. doi: 10.1002/ana.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mörk S, Bö L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Selak M, O'Connor J, Croul S, Lorenzana C, Butunoi C, et al. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and activity of mitochondrial enzymes in chronic active lesions of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2000;177:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte ME, Bø L, Rodenburg RJ, Belien JA, Musters R, Hazes T, et al. Enhanced number and activity of mitochondria in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Pathol. 2009;219:193–204. doi: 10.1002/path.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumleh HH, Riazi GH, Houshmand M, Sanati MH, Gharagozli K, Shafa M. Complex I deficiency in Persian multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci. 2006;243:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosley TM, Constantinescu CS, Tench CR, Abu-Amero KK. Mitochondrial changes in leukocytes of patients with optic neuritis. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1516–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M, Sparman M, Mitalipov S. Chromosome transfer in mature oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:e16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Shimada E, Zhang J, Hong JS, Smith GM, Teitell MA, et al. Correcting human mitochondrial mutations with targeted RNA import. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4840–4845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116792109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Koilkonda RD, Chou TH, Porciatti V, Ozdemir SS, Chiodo V, et al. Gene delivery to mitochondria by targeting modified adenoassociated virus suppresses Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E1238–E1247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119577109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacman SR, Williams SL, Garcia S, Moraes CT. Organ-specific shifts in mtDNA heteroplasmy following systemic delivery of a mitochondria-targeted restriction endonuclease. Gene Ther. 2010;17:713–720. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo BB, Kitajima-Ihara T, Chan EK, Scheffler IE, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Molecular remedy of complex I defects: rotenone-insensitive internal NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria restores the NADH oxidase activity of complex I-deficient mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9167–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Hájek P, Chomyn A, Chan E, Seo BB, Matsuno-Yagi A, et al. Lack of complex I activity in human cells carrying a mutation in MtDNA-encoded ND4 subunit is corrected by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NDI1) gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38808–38813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marella M, Seo BB, Thomas BB, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Successful amelioration of mitochondrial optic neuropathy using the yeast NDI1 gene in a rat animal model. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marella M, Seo BB, Flotte TR, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. No immune responses by the expression of the yeast Ndi1 protein in rats. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton N, Palfi A, Millington-Ward S, Gobbo O, Overlack N, Carrigan M, et al. Intravitreal delivery of AAV-NDI1 provides functional benefit in a murine model of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:62–68. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadorani S, Cho J, Lo T, Contreras H, Lawal HO, Krantz DE, et al. Neuronal expression of a single-subunit yeast NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Ndi1) extends Drosophila lifespan. Aging Cell. 2010;9:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCorby A, Gásková D, Sayles LC, Lemire BD. Expression of Ndi1p, an alternative NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, increases mitochondrial membrane potential in a C. elegans model of mitochondrial disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo BB, Marella M, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. The single subunit NADH dehydrogenase reduces generation of reactive oxygen species from complex I. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6105–6108. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sühs KW, Hein K, Sättler MB, Görlitz A, Ciupka C, Scholz K, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2 study of erythropoietin in optic neuritis. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:199–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.23573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau CR, Hein K, Sättler MB, Kretzschmar B, Hillgruber C, McRae BL, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of FTY720 do not prevent neuronal cell loss in a rat model of optic neuritis. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1770–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves MA. Adeno-associated virus: from defective virus to effective vector. Virol J. 2005;2:43. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, Hare J, Somasundaram T, Azzi A, et al. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10405–10410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162250899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, Cideciyan AV, Schwartz SB, Wang L, et al. Treatment of leber congenital amaurosis due to RPE65 mutations by ocular subretinal injection of adeno-associated virus gene vector: short-term results of a phase I trial. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:979–990. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, et al. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12:342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR, Laube BL. Gene therapy in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2001;120 3 Suppl:124S–131S. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3_suppl.124s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR. Immune responses to recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors: putting preclinical findings into perspective. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:716–717. doi: 10.1089/1043034041361190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, Fitzsimons HL, Mattis P, Lawlor PA, et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worgall S, Sondhi D, Hackett NR, Kosofsky B, Kekatpure MV, Neyzi N, et al. Treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis by CNS administration of a serotype 2 adeno-associated virus expressing CLN2 cDNA. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:463–474. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, McPhee SW, Li C, Gray SJ, Samulski JJ, Camp AS, et al. Phase 1 gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a translational optimized AAV vector. Mol Ther. 2012;20:443–455. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DM. Self-complementary AAV vectors; advances and applications. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1648–1656. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markusic DM, Herzog RW, Aslanidi GV, Hoffman BE, Li B, Li M, et al. High-efficiency transduction and correction of murine hemophilia B using AAV2 vectors devoid of multiple surface-exposed tyrosines. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2048–2056. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque S, Joussemet B, Riviere C, Marais T, Dubreil L, Douar AM, et al. Intravenous administration of self-complementary AAV9 enables transgene delivery to adult motor neurons. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1187–1196. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton F, Weiner HL, Jolesz FA, Guttmann CR. MRI contrast uptake in new lesions in relapsing-remitting MS followed at weekly intervals. Neurology. 2003;60:640–646. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000046587.83503.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MJ, Griffiths P, Turnbull DM, Bates D, Nichols P. The distributions of mitochondria and sodium channels reflect the specific energy requirements and conduction properties of the human optic nerve head. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:286–290. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.027664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasol J, Feuer W, Yang C, Shaw G, Kardon R, Guy J. Phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain correlations to visual function, optical coherence tomography, and treatment. Mult Scler Int. 2010;2010:542691. doi: 10.1155/2010/542691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrs-Silva H, Dinculescu A, Li Q, Min SH, Chiodo V, Pang JJ, et al. High-efficiency transduction of the mouse retina by tyrosine-mutant AAV serotype vectors. Mol Ther. 2009;17:463–471. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauswirth WW, Lewin AS, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Production and purification of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Meth Enzymol. 2000;316:743–761. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)16760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.