Abstract

Background/Aims

Many studies have shown that not only pharmacological treatment but also cognitive stimulation in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD) improves language processing and (other) cognitive functions, stabilizes Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) functions and increases the subjective quality of life (wherein a combination of pharmacological intervention and cognitive stimulation could provide greater relief of clinical symptoms than either intervention given alone). Today, it is no longer the question of whether cognitive stimulation helps but rather what kind of stimulation helps more than others.

Methods

A sample of 42 subjects with mild AD (all medicated with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and well adjusted) underwent clinical and cognitive evaluation and participated in a 6-month study with 2 experimental groups (i.e. ‘client-centered’ global stimulation vs. cognitive training) and a control group. Since the test performance also depends on the individual test, we used a wide variety of tests; we z-transformed the results and then calculated the mean value for the global cognitive status (using the Mini-Mental State Examination) as well as for the single functional areas.

Results

Between-group differences were found, they were overall in favor of the experimental groups. Different functional areas led to different treatment and test patterns. Client-centered, global, cognitive therapy stimulated many cognitive functions and thus led to a better performance in language processing and ADL/IADL. The subjective quality of life increased as well. The cognitive training (of working memory) improved only the ADL/IADL performance (more, however, than client-centered, global, cognitive stimulation) and stabilized the level of performance in the other three functional areas.

© 2013 S. Karger AG, Basel

Key Words : Alzheimer's disease, Cognitive stimulation therapy, Functional areas

Introduction

A large number of studies on cognitive stimulation therapy for early-stage Alzheimer's disease (AD) have shown that not only pharmacological treatments but also cognitive stimulation programs can help to stabilize or even improve performance globally and/or in single functional areas, e.g. cognitive functions, language processing, Activities of Daily Living/Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (ADL/IADL) functions and subjective quality of life [for a review, see [1,2,3,4,5]]. Frequently, stimulation programs are used in addition to medication [6,7]. But there are also studies on the effects of cognitive stimulation without medication [8,9]. Requena et al. [9] showed that a cognitive stimulation program without medication had significantly greater positive effects than medication without cognitive stimulation; however, a combination of medication and cognitive stimulation was the most effective (which is similar in most other studies). Normally, cognitive stimulation stabilizes the level of performance or even increases it in the first year (with or without medication); in the second year, the level of performance usually drops again – sometimes even below an initial level.

It is no longer the question of whether cognitive stimulation helps in AD, rather what kind of cognitive stimulation helps more than others.

Methods

For this research, a single-blind, randomized, controlled experiment of cognitive stimulation therapy was used. Although participants cannot be blinded to their allocated treatment, all follow-up data were collected and statistically analyzed by researchers who were blinded to the assigned experimental groups. Also the group randomization was done by project staff and hidden from the patients and groups.

Subjects

Our initial sample consists of 48 subjects with mild AD [fulfilling the DSM-IV and NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [10], Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥17 [11]]. All patients were medicated with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and were well adjusted (on this medication for at least 6 months). Six patients dropped out and were not considered further in the study (for more details, see table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Experimental group 1 (‘focus group’) | Experimental group 2 (‘training group’) | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n | 12 | 15 | 15 |

| Male | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Female | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 76.5 ± 3.503 | 74.2 ± 5.833 | 73.4 ± 4.837 |

| Range | 73–82 | 66–81 | 65–79 |

| Mean cognitive status ± SD, MMSE score | 23.75 ± 2.006 | 21.4 ± 2.971 | 21.2 ± 1.207 |

| Median | 24 | 21 | 21 |

| Range | 21–26 | 17–25 | 20–23 |

| Mean education ± SD, years | 8.75 ± 1.327 | 10.6 ± 3.906 | 10 ± 1.732 |

| Median | 8 | 9 | 11 |

| Range | 8–11 | 8–18 | 8–12 |

All participants were outpatients from the Freiburg area; almost half of the subjects were recruited through the ZGGF (Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, University of Freiburg i.Br., Germany). All participants were considered to have the abilities necessary to give their informed consent for taking part; appropriate care was taken in explaining the study and they were given sufficient time to reach a decision. It was made clear to all patients that they would not be disadvantaged if they chose not to participate in the half-year study on cognitive stimulation. Before the initial assessment, the participants were randomized into 3 groups: 2 experimental groups and 1 control group (acetylcholinesterase inhibitor only). As regards the demographic and baseline characteristics, the 3 groups did not show any statistically relevant differences.

We used the following exclusion criteria: other psychiatric or neurological disorders; a score on the ‘reduced’ geriatric depression scale [12] of 5-15 points); receiving psychotropic drugs; impairments of the peripheral vision and hearing (audiometer, visual acuity test, hearing and reading comprehension tests), and a mother tongue other than German.

Materials

The central hypothesis about the causes of most cognitive deficits in mild AD is the working memory hypothesis. There are 2 kinds of explanations possible. Authors like Almor et al. [13] have argued that the capacity of the working memory is reduced. More specifically, the time in which representations are available in the working memory is reduced. However, there are also many indications that the processing speed of executive processes is slowed down (‘cognitive slowing’), so that the temporal capacity of the (undisturbed) working memory is not sufficient for processing.

Based on the working memory hypothesis, we developed 2 kinds of cognitive stimulations. First, we designed a training program for the mental presentation of complex context relations in the working memory (which was implemented in our ‘training group’). Such training (conducted in small groups) affects both the capacity of the working memory and the processing speed of executive processes. Second, we expounded upon the model by Stuss and Benson [14], in which the self is regarded as the highest executive authority [for further reading on executive functions in detail, see also [15]] and at the same time as the metacognitive authority. The self is capable of supporting executive processing and such support is usually unconscious. In order to stimulate the self, we organized discussions on sensitive issues (e.g. ‘sexual relations before marriage’ or ‘having children at an older age’) and discussed these topics in small ‘focus groups’, in the format of a rather confrontational debate.

Procedure

All participants underwent several tests and retests (table 2). In order to make more detailed statements, we broke larger batteries of tests down into subtests [e.g. the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale – cognition (ADAS-cog) or the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD plus)]; we then categorized these subtests into 4 functional areas: cognition, language processing (= ‘language’), ADL/IADL (functions) and subjective quality of life (= ‘quality of life’). Cognition refers to cognitive processing without language processing and ADL/IADL functions. By assigning a test to a functional area, we sought to examine which functions are primarily being tested.

Table 2.

Tests and subtests, test batteries and functional areas

| Test/subtest | Test battery | Functional area | Direction of analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Fluency | *CERAD-plus | [23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] | cognition | ⇑ = + |

| Boston Naming | CERAD-plus | language | ⇑ = + | |

| MMSE | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Ten-Item Word Recall | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Word List Recognition | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Delayed Recall of Word List Items | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Constructional Praxis | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Delayed Recall of Praxis Items | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Trail Making Test A (numbers) | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇓ = + | |

| Trail Making Test B | CERAD-plus | cognition | ⇓ = + | |

| Word-Form Fluency | CERAD-plus | language | ⇑ = + | |

| Trail Making Test A (letters) | cognition | ⇓ = + | ||

| Clock Drawing | [16] | cognition | ⇑ = + | |

| Execution of Instructions | ADAS-cog | [29, 30] | cognition | ⇓ = + |

| Naming | ADAS-cog | language | ⇓ = + | |

| Verbal Production | ADAS-cog | language | ⇓ = + | |

| Verbal Comprehension | ADAS-cog | language | ⇓ = + | |

| Appropriate Word-Finding | ADAS-cog | language | ⇓ = + | |

| Barthel Index | [17, 18] | ADL/IADL | ⇑ = + | |

| IADL | [19] | ADL/IADL | ⇑ = + | |

| Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste | [20, 21, 22] | quality of life | ⇑ = + | |

| Self-Assessment | Bayer-ADL | [31, 32] | ADL/IADL | ⇓ = + |

| External Assessment | Bayer-ADL | ADL/IADL | ⇓ = + | |

| Patient Survey: Feelings | Dem-Quol | [33, 34] | quality of life | ⇓ = + |

| Patient Survey: Memory | Dem-Quol | cognition | ⇓ = + | |

| Patient Survey: Circumstances (of living) | Dem-Quol | quality of life | ⇓ = + | |

| Family Survey: Circumstances (of living) | Dem-Quol | quality of life | ⇓ = + | |

| Family Survey: Memory | NOSGER | [35, 36] | cognition | ⇓ = + |

| IADL | NOSGER | ADL/IADL | ⇓ = + | |

| ADL | NOSGER | ADL/IADL | ⇓ = + | |

| Mood | NOSGER | quality of life | ⇓ = + | |

The version ‘*CERAD-plus’ is available from the ‘Memory Clinic’ in Basel, Switzerland. Dem-Quol = Development of a New Measure of Health-Related Quality of Life for People with Dementia; NOSGER = Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients. The string ‘ ⇓ = +’ means that the lower the values are, the higher the performance will be (see for instance reaction times). Conversely, the string ‘ ⇑ = +’ means that the higher the values are, the higher the performance will be.

Based on our previous experience, as the performance of a participant can be classified differently according to the particular type of test used, we utilized a large number of tests and transformed the results into z values.

The results of the performance tests in each group were very inhomogeneous. This also applies to the test results at the end of the treatment phase. Therefore, we did not compare the mean values of the groups before and after the treatment phase. But we determined the differences between the results before and after the treatment phase for each subject individually (table 3).

Table 3.

All scale-individual between-groups ANOVAs and t tests

| Test/subtest | Direction | Mean values1 |

ANOVA – Pr(>F) | Magnitude of effect | t tests, p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| group 1 | group 2 | group 3 | group 1 vs. group 2 | group 2 vs. group 3 | group 1 vs. group 3 | ||||

| Verbal Fluency | ⇑ = + | 0.800 | 0.400 | −2.833 | 0.0980 | 0.7180 | 0.1799 | 0.1262 | |

| Boston Naming | ⇑ = + | −0.25 | −0.40 | −0.80 | 0.3966 | 0.6526 | 0.3001 | 0.1810 | |

| MMSE | ⇑ = + | 0.25 | 0.20 | −0.60 | 0.0483* | 0.0944 | 0.9678 | 0.0311* | 0.0472 |

| 0.1143 | 0.0965 | −0.1879 | |||||||

| Ten-Item Word Recall | ⇑ = + | −1.5 | 0.4 | −1.0 | 0.4131 | 0.08042 | 0.3643 | 0.7556 | |

| Word List Recognition | ⇑ = + | 2.25 | −1.60 | 1.00 | 0.2986 | 3.013e–6* | 0.001296* | 0.1238 | |

| Delayed Recall of Word List | ⇑ = + | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.007401* | 0.1237 | 0.01360* | 0.1093 | 0.1879 |

| 0.3744 | −0.3153 | 0.0158 | |||||||

| Constructional Praxis | ⇑ = + | −1.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1835 | 0.02061* | 0.8047 | 0.1767 | |

| Delayed Recall of Praxis Items | ⇑ = + | 0.75 | 1.00 | −0.20 | 0.005749* | 0.1220 | 0.6955 | 0.000652* | 0.1438 |

| 0.0374 | 0.2671 | −0.3739 | |||||||

| Trail Making Test A (numbers) | ⇓ = + | −5.5 | 28.0 | −14.0 | 0.5466 | 0.00589* | 0.0867 | 0.6997 | |

| Trail Making Test A (letters) | ⇓ = + | −67.5 | −77.8 | −20.0 | 0.006042* | 0.1304 | 0.799 | 0.2107 | 0.09068* |

| −0.0730 | −0.1296 | 0.1880 | |||||||

| 0.0730 | 0.1296 | −0.1880 | |||||||

| Trail Making Test B | ⇓ = + | −107 | −179 | −19 | 1.182e–5* | 0.3661 | 0.1373 | 0.002446* | 0.0002375* |

| −0.0304 | −0.4141 | 0.4384 | |||||||

| 0.0304 | 0.4141 | −0.4384 | |||||||

| Word-Form Fluency | ⇑ = + | 2.75 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.01239* | 0.1070 | 0.08721 | 0.8846 | 0.03451* |

| 0.4648 | −0.1576 | −0.2156 | |||||||

| Clock Drawing | ⇑ = + | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 0.000644* | 0.2084 | 0.0457* | 0.5272 | 0.5769 |

| 0.1832 | −0.1665 | 0.0110 | |||||||

| Execution of Instructions | ⇓ = + | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.1401 | 0.2030 | 0.07251 | 0.7861 | |

| Naming | ⇓ = + | −0.75 | 1.40 | 1.00 | 0.6618 | 4.647e–6* | 0.2247 | 1.115e–5* | |

| Verbal Production | ⇓ = + | −0.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.01116* | 0.1104 | 0.03667* | 0.04251* | 0.0001533* |

| −0.7930 | 0.00 | 0.6344 | |||||||

| 0.7930 | 0.00 | −0.6344 | |||||||

| Verbal Comprehension | ⇓ = + | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.594 | 0.6013 | 0.1251 | 0.1974 | |

| Appropriate Word-Finding | ⇓ = + | −0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5321 | 0.01857* | 0.1885 | 0.06899 | |

| Barthel Index | ⇑ = + | −1.00 | 2.00 | −6.25 | 0.003964* | 0.2338 | 0.02051* | 1.153e–6* | 2.538e–6* |

| 0.1257 | 1.0059 | −1.4145 | |||||||

| IADL | ⇑ = + | −0.25 | −0.40 | −0.80 | 0.1152 | 0.6777 | 0.1866 | 0.2038 | |

| Münchner Lebensqualitäts | ⇑ = + | 17.5 | −5.8 | −4.8 | 0.02289* | 0.0878 | 3.013e–5* | 0.8883 | 0.00267* |

| Dimensionen Liste | 0.6396 | −0.2755 | −0.2362 | ||||||

| Self-Assessment | ⇓ = + | 19.25 | 13.20 | 52.00 | 0.2424 | 0.5385 | 0.006874* | 0.00978* | |

| External Assessment | ⇓ = + | 8.0 | −12.5 | 25.4 | 0.2555 | 0.2500 | 0.02413* | 0.3045 | |

| Patient Survey: Feelings | ⇓ = + | −1.0 | −2.4 | 0.4 | 0.3198 | 0.5743 | 0.3088 | 0.5398 | |

| Patient Survey: Memory | ⇓ = + | −3.0 | 0.8 | −0.4 | 0.1241 | 7.791e–5* | 0.5382 | 0.1741 | |

| Patient Survey: Circumstances | ⇓ = + | −1.5 | −0.8 | −4.2 | 0.55 | 0.7435 | 0.1005 | 0.07753 | |

| Family Survey: Circumstances | ⇓ = + | −2.3 | −1 | 4 | 5.081e–7* | 0.9951 | 0.2339 | 2.480e–5* | 2.692e–6* |

| −0.6498 | −0.3601 | 0.7544 | |||||||

| 0.6498 | 0.3601 | −0.7544 | |||||||

| Family Survey: Memory | ⇓ = + | −2.0 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.974e–5* | 0.5545 | 1.229e–5* | 0.7626 | 4.594e–5* |

| −1.1953 | 0.8464 | −0.4392 | |||||||

| 1.1953 | −0.8464 | 0.4392 | |||||||

| IADL | ⇓ = + | −1.75 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 0.006692* | 0.2046 | 0.3291 | 0.03612* | 0.02930* |

| −0.5413 | −0.0917 | 0.5248 | |||||||

| 0.5413 | 0.0917 | −0.5248 | |||||||

| ADL | ⇓ = + | −1.25 | −0.40 | −0.80 | 0.5884 | 0.2666 | 0.592 | 0.4733 | |

| Mood | ⇓ = + | −1.5 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.070e–5 | 0.5818 | 0.00108* | 0.2356 | <0.001* |

| −0.2626 | 0.8770 | 1.1711 | |||||||

| 0.2626 | −0.8770 | −1.1711 | |||||||

Group 1 = ‘Focus group’; group 2 = ‘training group’; group 3 = controls. In the ANOVA and t test columns, all statistically significant results are printed with an asterisk.

Some fields contain 2 or 3 lines of values. The first line shows the group's mean value, the second line (in bold) shows the z-transformed mean value and the third line (also in bold) contains the direction of the analysis.

Results

Table 3 shows the groups' mean values of individual differences before and after the treatment phase, the results of the one-way ANOVA, the results when comparing one group with another and the effect size.

Z-standardization is a statistical standard procedure that maps a normal curve to a standard normal curve and thus makes different scales and distributions comparable without losing their discriminatory information, i.e. it makes different scales of a similar or the same construct comparable. For the z-transformation, we used (1) the groups' mean value x of the differences before and after the treatment phase (per test), (2) the overall mean AMx of the differences before and after the treatment phase (also for each test), and (3) the standard deviation SDx of all results (before and after the treatment phase, again per test). The z values were then calculated as follows:

which leads to (between-test) intercomparable, standardized, normal distributions with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

In table 3, all statistically significant ANOVA and t test results are indicated by an asterisk. The magnitude of effect is calculated as the proportion of explained variance divided by the error variance.

The unstructured overview of the different test scores says little about the cognitive performance of the subjects. So in table 4, we divided cognitive performance into 4 functional areas (see above), to which we then assigned those tests from table 3 which were statistically significant within the ANOVA.

Table 4.

Mean z values (and statistically significant differences)

| Test | z value |

p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| group 1 | group 2 | group 3 | group 1 vs. group 2 | group 2 vs. group 3 | group 1 vs. group 3 | |

| Cognition | ||||||

| MMSE | 0.1143 | 0.0965 | −0.1879 | 0.0311* | 0.0472* | |

| Delayed Recall of Word List | 0.3744 | −0.3153 | 0.0158 | 0.01360* | ||

| Delayed Recall of Praxis Items | 0.0374 | 0.2671 | −0.3739 | 0.000652* | ||

| Clock Drawing | 0.1832 | −0.1665 | 0.0110 | 0.0457* | ||

| Family Survey: Memory | 1.1953 | −0.8464 | −0.4392 | 1.229e–5* | 4.594e–5* | |

| Trail Making Test A (letters) | 0.0730 | 0.1296 | −0.1880 | 0.09068* | ||

| Trail Making Test B | 0.0304 | 0.4141 | −0.4384 | 0.002446* | 0.0002375* | |

| Mean | 0.2869 | −0.0601 | −0.2287 | |||

| Language processing | ||||||

| Word-Form Fluency | 0.4648 | −0.1576 | −0.2156 | 0.03451* | ||

| Verbal Production | 0.7930 | 0.00 | −0.6344 | 0.03667* | 0.04251* | 0.0001533* |

| Mean | 0.6289 | −0.0788 | −0.425 | |||

| ADL/IADL | ||||||

| Barthel Index | 0.1257 | 1.0059 | −1.4145 | 0.02051* | 1.153e–6* | 2.538e–6* |

| IADL | 0.5413 | 0.0917 | −0.5248 | 0.03612* | 0.02930* | |

| Mean | 0.3335 | 0.5488 | −0.9697 | |||

| Quality of life | ||||||

| Münchner Lebensqualitäts | 0.6396 | −0.2755 | −0.2362 | 3.013e–5* | 0.00267 | |

| Dimensionen Liste | ||||||

| Family Survey: Circumstances | 0.6498 | 0.3601 | −0.7544 | 2.480e–5* | 2.692e–6* | |

| Mood | 0.2626 | −0.8770 | −1.1711 | 0.00108* | 0.0001846* | |

| Mean | 0.5173 | −0.2641 | −0.7206 | |||

Group 1 = ‘Focus group’; group 2 = ‘training group’; group 3 = controls.

Table 5 summarizes the effect sizes for the functional areas of cognitive performance; under functional area ‘cognition’, we subdivided further and give those tests that measure cognitive processing speed separately (= ‘cognition II’). In social sciences, effect sizes between approximately 0.1 and 0.2 are already considered to have a medium effect size, values up to approximately 0.5 are considered to have a high effect size and values greater than approximately 0.5 are considered to have a very high effect size.

Table 5.

Effect sizes (partial η2 of the ANOVAs)

| Functional area | Test | η2 | Aggr (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition I | MMSE | 0.0944 | 0.2206 |

| Delayed Recall of Word List | 0.1237 | ||

| Delayed Recall of Praxis Items | 0.1220 | ||

| Clock Drawing | 0.2084 | ||

| Family Survey: Memory | 0.5545 | ||

| Cognition II | Trail Making Test A (letters) | 0.1304 | 0.2483 |

| Trail Making Test B | 0.3661 | ||

| Language processing | Word-Form Fluency | 0.1070 | 0.1087 |

| Verbal Production | 0.1104 | ||

| ADL/IADL | Barthel Index | 0.2338 | 0.2192 |

| IADL | 0.2046 | ||

| Quality of life | Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste | 0.0878 | 0.5549 |

| Family Survey: Circumstances | 0.9951 | ||

| Mood | 0.5818 | ||

Discussion

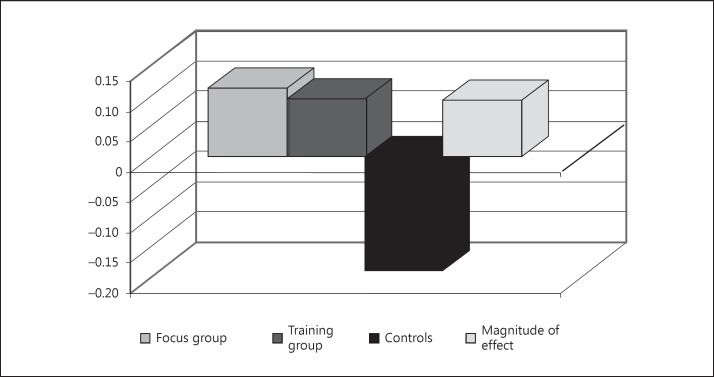

The results of the MMSE are considered to give an overview of the cognitive performance of the patients. The bar chart in figure 1 compares the corresponding mean values of the individual differences before and after the treatment phase. The 2 experimental groups hardly differ from each other. However, there are great differences (with medium effect sizes) between the 2 experimental groups and the control group. This might lead to the false conclusion that any non-drug intervention helps and that the only important thing is that something is being done at all.

Fig. 1.

Mean MMSE scores of the individual differences before and after the treatment phase.

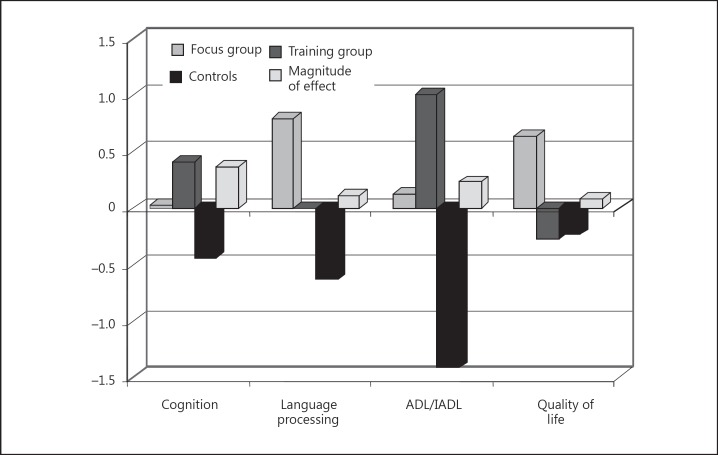

The picture changes, however, when we compare each functional area separately. It should be kept in mind that we assumed that language processing and ADL/IADL are also cognitive areas; cognition refers to the cognitive performance without the performance in the language processing and in the ADL/IADL area. In figure 2, performance in the cognition area was measured using the Trail Making Test B, performance in the language processing area was measured using Verbal Production (ADAS-cog, third part of the test), performance in the ADL/IADL area was measured using the Barthel Index and performance in the quality of life area was measured using the ‘Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste’. Again, in the cognition, language processing and ADL/IADL areas, experimental groups 1 and 2 clearly showed better results than the control group. However, in the quality of life area, only the focus group but not the training group showed better results than the control group. This is possibly so because the participants in the training group were confronted once again with their deficits. It is striking that the training group has clearly better results in the ADL/IADL area than the focus group. Is there a transfer effect? Does training of the working memory performance also help in ADL functions? Yet, why does training of the working memory performance demonstrate clearly smaller effects in the language processing area than a confrontational discussion of problematic issues? Perhaps a dedicated discussion of problematic issues activates much broader language skills in particular and cognitive abilities in general. But why is this the case, given that the training group clearly had higher values than the focus group in the cognition area?

Fig. 2.

Comparison A of the 3 groups and the 4 functional areas. Performance in the cognition area was measured using the Trail Making Test B; performance in the language processing area was measured using Verbal Production (ADAS-cog, part 3); performance in the ADL/IADL area was measured using the Barthel Index; performance in the quality of life area was measured using the Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste.

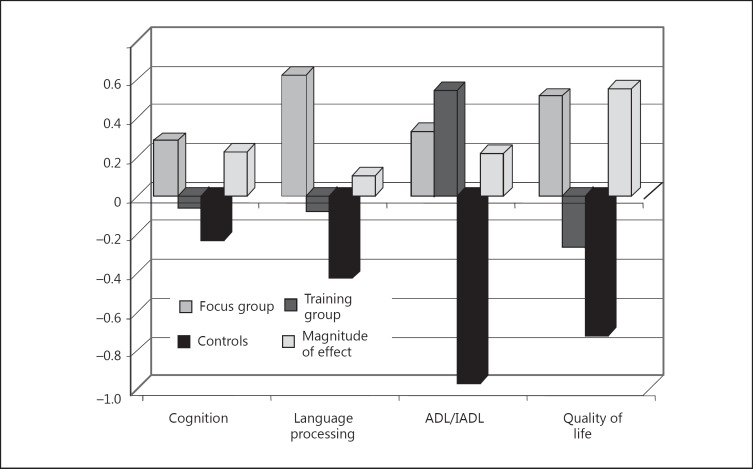

The overview in figure 2 is misleading. The results depend on the tests used. In figure 3, we used the mean values for the functional areas. The following aspects have to be noted. (1) Indeed, a dedicated discussion of problematic issues activated much broader language skills in particular (with small effect sizes) and cognitive abilities in general (see figure 3, the group of bars on the left – with medium effect sizes). (2) In fact, training of the working memory – unlike a dedicated discussion – led to a low effect in the quality of life area; however, the assessment in the control group was even more reduced than in the training group. In contrast, in the focus group, there were clearly increases in the evaluation of the subjective quality of life (with very high effect sizes). (3) In addition, training of the working memory performance also increased ADL skills (with medium effect sizes), more so than the discussion of problematic issues (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison B – mean values of the functional areas.

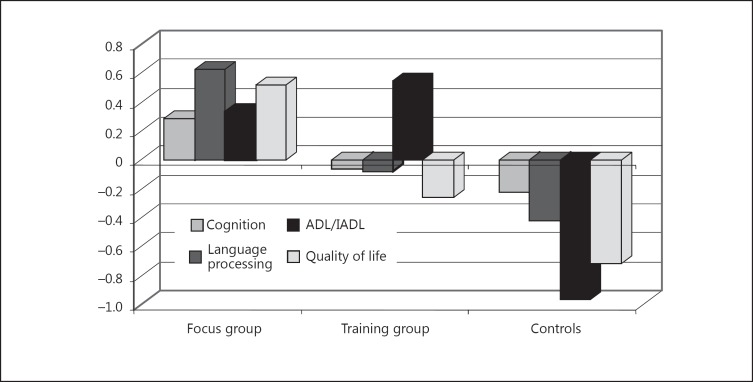

Figure 4 presents the data from figure 3 in a slightly different combination. From this new compilation of the data, it becomes clear that the focus group (discussing relevant issues) as a whole achieved better results. The results of the training group were only better in the ADL/IADL area.

Fig. 4.

Comparison C of the 3 groups and the 4 functional areas – new compilation of the data in figure 3.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

- 1.Clare L, Woods RT. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease: a review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2004;14:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spector A, Woods B, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:751–757. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clare L, Woods B. Cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive training for early-stage Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD003260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu F, Rose K, Burgener S, Cunningham C, Buettner L, Beattie E, Bossen A, Buckwalter K, Fick D, Fitzsimmons S, Kolanowski A, Specht J, Richeson N, Testad I, McKenzie S. Cognitive training for early-stage Alzheimer's disease and dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35:23–29. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20090301-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuckuk R.Kognitive Stimulation bei Demenzen vom Alzheimer-Typ (DAT) in frühen bis mittleren Stadien: Eine qualitative Analyse internationaler Forschungsergebnisse; Dissertation, Universität Freiburg i.Br., 2010.

- 6.Chapman SB, Weiner MF, Rackley A, Hynan LS, Zients J. Effects of cognitive-communication stimulation for Alzheimer's disease patients treated with donepezil. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2004;47:1149–1163. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/085). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottino CM, Carvalho IA, Alvarez AM, Avila R, Zukauskas PR, Bustamante SE, Andrade FC, Hototian SR, Saffi F, Camargo CH. Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease patients: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:861–869. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr911oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Möller G.Therapeutische Möglichkeiten bei Alzheimer-Demenz: Evaluation des integrativen/interaktiven Hirnleistungstrainings (IHT) der Heiliggeistspitalstiftung Freiburg; Dissertation, Universität Freiburg i.Br., 2001.

- 9.Requena C, Maestú F, Campo P, Fernández A, Ortiz T. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia: 2-year follow-up. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:339–345. doi: 10.1159/000095600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang VS, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almor A, Kempler D, MacDonald MC, Andersen ES, Tyler LK. Why do Alzheimer patients have difficulty with pronouns? Working memory, semantics, and reference in comprehension and production in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Lang. 1999;67:202–227. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuss DT, Benson DF. The Frontal Lobes. New York: Raven Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuss DT, Alexander MP. Is there a dysexecutive syndrome? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:901–915. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulman KI, Gold DP. Clock drawing and dementia in the community. A longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. MD State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bös K. Barthel-Index. In: Bös K, editor. Handbuch Motorische Tests: Sportmotorische Tests, motorische Funktionstests, Fragebogen zur körperlich-sportlichen Aktivität und sportpsychologische Diagnoseverfahren. Göttingen and Bern: Hogrefe; 2001. pp. 305–307. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franz M, Plüddemann K, Gruppe H, Gallhofer B. Modifikation und Anwendung der Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen-Liste bei schizophrenen Patienten. In: Müller HJ, Engel RR, Hopf P, editors. Befunderhebung in der Psychiatrie: Negativsymptomatik, Lebensqualität und andere neue Entwicklungen. Wien: Springer; 1996. pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinisch M, Ludwig M, Bullinger M. Psychometrische Testung der ‘Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste’ (MLDL) In: Bullinger M, Ludwig M, von Steinbüchel N, editors. Lebensqualität bei kardiovaskulären Erkrankungen: Grundlagen, Messverfahren und Ergebnisse. Göttingen and Bern: Hogrefe; 1991. pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinisch M, Ludwig M, Bullinger M. MLDL. Münchner Lebensqualitäts Dimensionen Liste. In: Strauss B, Schumacher J, editors. Klinische Interviews und Ratingskalen. Göttingen and Bern: Hofgrefe; 2005. pp. 224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JC, Mohs RC, Rogers H, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:641–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, Beekly D, Edland S, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). 5. A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44:609–614. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berres M, Monsch AU, Bernasconi F, Thalmann B, Stähelin HB. Normal ranges of neuropsychological tests for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2000;77:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thalmann B, Monsch AU, Schneitter M, Bernasconi F, Aebi C, Camachova Davet Z, et al. The CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery (CERAD-NAB) – A minimal data set as a common tool for German-speaking Europe. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(suppl 1):30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aebi C.Validierung der neuropsychologischen Testbatterie CERAD-NP: eine Multi-Center Studie; Dissertation, Universität Basel, 2002.

- 28.Ehrensperger MM, Berres M, Taylor KI, Monsch AU. Early detection of Alzheimer's disease with a total score of the German CERAD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16:910–920. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. ADAS. Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale. In: Strauss B, Schumacher J, editors. Klinische Interviews und Ratingskalen. Göttingen and Bern: Hogrefe; 2005. pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hindmarch I, Lehfeld H, de Jongh P, Erzigkeit H. The Bayer Activities of Daily Living Scale (B-ADL) Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9(suppl 2):20–26. doi: 10.1159/000051195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erzigkeit H, Lehfeld H, Peña-Casanova J, Bieber F, Yekrangi-Hartmann C, Rupp M, Rappard F, Arnold K, Hindmarch I. The Bayer-Activities of Daily Living Scale (B-ADL): results from a validation study in three European countries. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12:348–358. doi: 10.1159/000051280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, Cook JC, Murray J, Prince M, Levin E, Mann A, Knapp M. Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:1–93. doi: 10.3310/hta9100. iii-iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, Smith SC, Lamping DL, Harwood RH, Foley B, Smith P, Murray J, Prince M, Levin E, Mann A, Knapp M. Quality of life in dementia: more than just cognition. An analysis of associations with quality of life in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:146–148. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel R, Brunner C, Ermini-Fünfschilling D, Monsch AU, Notter M, Puxty J, Tremmel L. A new behavioral assessment scale for geriatric out- and in-patients: the NOSGER (Nurses' Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients) J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiegel R. NOSGER. Nurses' Obersavtion Scale for Geriatric Patients. In: Strauss B, Schumacher J, editors. Klinische Interviews und Ratingskalen. Göttingen and Bern: Hogrefe; 2005. pp. 276–279. [Google Scholar]