Abstract

Clinical studies have shown that statin use may alter the risk of lung cancer. However, these studies yielded different results. To quantify the association between statin use and risk of lung cancer, we performed a detailed meta-analysis. A literature search was carried out using MEDLINE, EMBASE and COCHRANE database between January 1966 and November 2012. Before meta-analysis, between-study heterogeneity and publication bias were assessed using adequate statistical tests. Fixed-effect and random-effect models were used to calculate the pooled relative risks (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analysis and cumulative meta-analysis were also performed. A total of 20 (five randomized controlled trials, eight cohorts, and seven case–control) studies contributed to the analysis. Pooled results indicated a non-significant decrease of total lung cancer risk among all statin users (RR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.78, 1.02]). Further, long-term statin use did not significantly decrease the risk of total lung cancer (RR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.39 , 1.64]). In our subgroup analyses, the results were not substantially affected by study design, participant ethnicity, or confounder adjustment. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of results. The findings of this meta-analysis suggested that there was no significant association between statin use and risk of lung cancer. More studies, especially randomized controlled trials and high quality cohort studies are warranted to confirm this association.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1,2]. The age-adjusted incidence rate of lung cancer was 62.6 per 100,000 men and women per year, and the age-adjusted death rate was 50.6 per 100,000 men and women per year[3]. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) are the most commonly used drugs in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, which potently reduce plasma cholesterol levels. Their efficacy on cardiovascular events has been proven irrefutably for both reduction of morbidity and mortality[4,5]. Rodent studies suggested that statins may be carcinogenic[6]. However, several preclinical studies have shown that statins may have potential anticancer effects through arresting of cell cycle progression[7], inducing apotosis[8,9], suppressing angiogenesis[10,11], and inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis[12,13]. For lung cancer, some experimental studies have found that statin may induces apoptosis[14–18], inhibit tumor growth[19–22], angiogenesis[23], as well as metastasis[24]. Further, statin may overcome drug resistance in human lung cancer[25]. Now there are some studies investigating the association between statin use and lung cancer, however, the existing results are controversial. To better understand this issue, we carried out a meta -analysis of existing randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational studies that investigated the association between statins use and the risk of developing lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

The meta-analysis was undertaken in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)[26]. A literature search was carried out using MEDLINE, EMBASE and COCHRANE databases between January 1966 and November 2012. There were no restriction of origin and languages. Search terms included: ‘‘hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor(s)’’ or ‘‘statin(s)’’ or ‘‘lipid-lowering agent(s)’’ and ‘‘cancer(s)’’ or ‘‘neoplasm(s)’’ or ‘‘malignancy(ies)’’. The reference list of each comparative study and previous reviews were manually examined to find additional relevant studies.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently selected eligible trials. Disagreement between the two reviewers was settled by discussing with the third reviewer. Inclusion criteria were: (i) an original study comparing statin treatment with an inactive control (placebo or no statins), (ii) adult study participants (18 years or older), (iii) presented odds ratio (OR), relative risk (RR), or hazard ratio (HR) estimates with its 95% confidence interval (CI), or provided data for their calculation., and (iv)follow-up over one year. Studies without lung cancer assessment and those describing statin treatment in cancer or transplant patients were excluded. When there were multiple publications from the same population, only data from the most recent report were included in the meta-analysis and remaining were excluded . Studies reporting different measures of RR like risk ratio, rate ratio, HR, and OR were included in the meta-analysis. In practice, these measures of effect yield a similar estimate of RR, since the absolute risk of lung cancer is low.

Data extraction

The following data was collected by two reviewers independently using a purpose-designed form: name of first author, publishing time, country of the population studied, study design, study period, patient characteristics, statin type, the RR estimates and its 95 % CIs, confounding factors for matching or adjustments.

Methodological quality assessment

The quality of included randomized controlled trials (RCT) was assessed using the tool of “risk of bias” according to the Cochrane Handbook. Sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data and selective reporting were assessed, and each of them was graded as “yes(+)”, “no(-)” or “unclear(?)”, which reflected low risk of bias, high risk of bias and uncertain risk of bias, respectively. We used Newcastle-Ottawa scale to assess the methodologic quality of cohort and case–control studies. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale contains eight items that are categorized three categories: selection (four items, one star each), comparability (one item, up to two stars), and exposure/outcome (three items, one star each). A ‘‘star’’ presents a ‘‘high-quality’’ choice of individual study. Two reviewers who were blinded regarding the source institution, the journal, and the authors for each included publication independently assess the methodologic quality. Disagreement between the two reviewers was settled by discussing with the third reviewer.

Data synthesis and analysis

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q and I2 statistics. For the Q statistic, a P value<0.10 was considered statistically significant for heterogeneity; for the I2 statistic, heterogeneity was interpreted as absent (I2: 0%–25%), low (I2: 25.1%–50%), moderate (I2: 50.1%–75%), or high (I2: 75.1%–100%)[27]. The overall analysis including all eligible studies was performed first, and subgroup analyses were performed according to (i) study design (RCT, cohort and case–control studies), (ii) study location, and (iii)control for confounding factors ( n ≥ 8, n ≤ 7) , to examine the impact of these factors on the association. We also assessed the link between long-term statin use and lung cancer risk. Pooled RR estimates and corresponding 95 % CIs were calculated using the inverse variance method. In the absence of a statistically significant heterogeneity (I2: 0%–25%), fixed model was used; otherwise, random model was performed. To test the robustness of association and characterize possible sources of statistical heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was carried out by excluding studies one-by-one and analyzing the homogeneity and effect size for all of rest studies. Publication bias was assessed using Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test and the Egger regression asymmetry test[28,29]. All analyses were performed using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Search results and characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

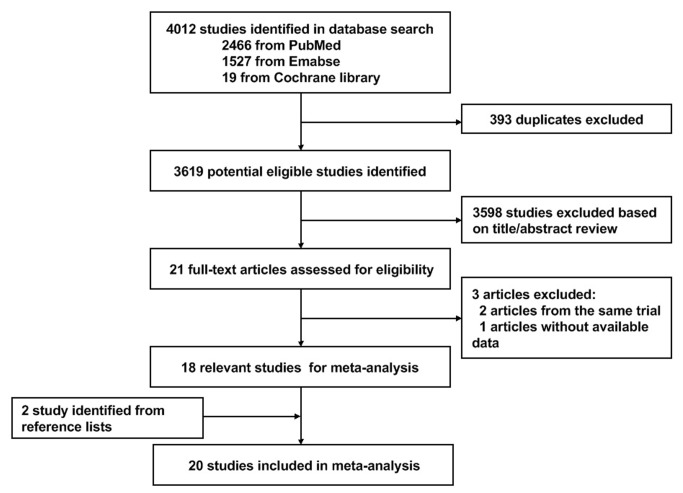

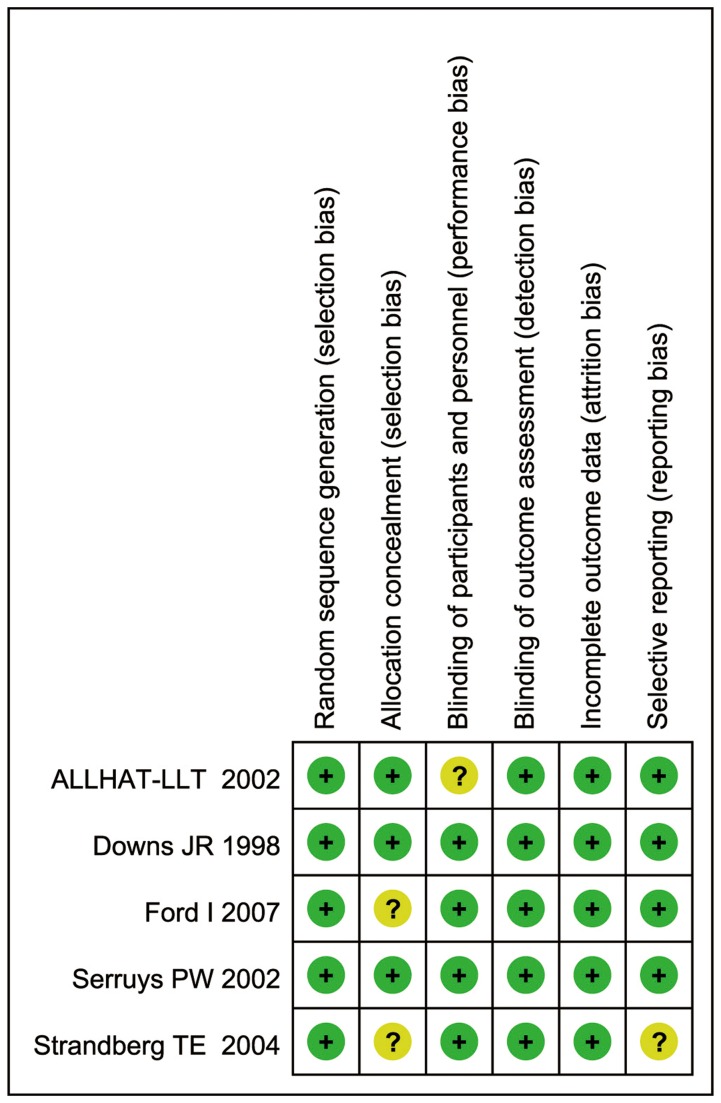

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for study inclusion. A total of 4012 citations were identified during the initial search. On the basis of the title and abstract, we identified 21 papers. After detailed evaluation, three studies were excluded for reasons described in Figure 1 . Two studies were identified from reference lists. At last, the remaining 20 studies published between 1998 and 2012 were included in the meta-analysis, with five RCTs[30–34], eight cohort studies[35–42], and seven case–control studies[43–49] (Baseline data and other details are shown in Table 1 ). A total of 4,980,009 participants, including 37,560 lung cancer cases were involved. Of the 20 included studies, nine studies were conducted in America, nine in Europe, and the remaining two in Asia. Further, six studies[38,41,42,45,48,49] were reported RR estimates of the association between long-term statin use and risk of lung cancer (Table 2 ). Figure 2. illustrates our opinion about each item of bias risk for included RCTs, most of the items were at“low risk” based on Cochrane handbook, suggesting a reasonable good quality of RCTs. Table 3 summarizes the quality scores of cohort studies and case-control studies. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores for the included studies ranged from 4 to 9, with a median 6; 9 studies (60%) were deemed to be of a high quality (≥6).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of screened, excluded, and analysed publications.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Study period | Treated n/N or cases n/N | Contros n/N | Statin type | Confounders for adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downs JR | 1998 | USA | RCT | 1990-1997 | 22/3,304 | 17/3,301 | L | Randomization |

| Blais L | 2000 | Canada | case-control | 1988–1994 | NR/70 | NR/700 | L, P, S | age, sex, use of fibric acid, use of other lipid-reducing agents, previous benign neoplasm, year of cohort entry, the score of comorbidity |

| Serruys PW | 2002 | Netherlands | RCT | 1996-1998 | 5/844 | 3/833 | F | Randomization |

| ALLHAT-LLT | 2002 | USA | RCT | 1994-2002 | 63/5,170 | 78/5,185 | P | Randomization |

| Strandberg TE | 2004 | Nordic countries | RCT | 1988-1994 | 25/2,221 | 31/2,223 | S | Randomization |

| Graaf MR | 2004 | Netherlands | case-control | 1995–1998 | NR/449 | 986/16,976 | A, C, F, P, S | age, sex, geographic region, follow-up time, calendar time, diabetes mellitus, chronic use of diuretics, use of ACE inhibitors,use of calcium antagonists, use of NSAIDs, use of hormones, other lipid-lowering therapies, familiar hypercholesterolemia |

| Kaye JA | 2004 | UK | case-control | 1990–2002 | 43/605 | 1066/14,844 | NR | age, BMI,smoking |

| Friis S | 2005 | Denmark | cohort | 1989–2002 | 73/12,251 | 3326/336,011 | A, C, F, L, P, S | age, sex, calendar period, use of NSAIDs, use of hormone, use of cardiovascular drugs |

| Sato S | 2006 | Japan | cohort | 1991-1995 | 1/179 | 1/84 | P | age, sex, total serum cholesterol level, smoking |

| Ford I | 2007 | UK | RCT | 1989-1991 | 102/3,291 | 109/3,286 | P | Randomization |

| Coogan PF | 2007 | USA | case-control | 1991-2005 | 31/464 | 190/3,900 | NR | age, sex, BMI, interview year, study center, alcohol consumption, race, years of education, smoking, use of NSAID |

| Khurana V | 2007 | USA | case-control | 1998-2004 | 1,994/7,280 | 161,668/476,453 | NR | age, sex, race, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus |

| Setoguchi S | 2007 | USA | cohort | 1994–2003 | 179/24,439 | 37/7,284 | A, C, F, L, P, S | age, use of NSAIDs, use of hormones, diabetes mellitus, comorbidity score, number of physician visits, prior hospitalization, arthritis, obesity, smoking |

| Friedman GD | 2008 | USA | cohort | 1994-2003 | 614/361,859 | NR/NR | A, C, F, L, P, R, S | smoking, use of NSAIDs, calendar year |

| Farwell WR | 2008 | USA | cohort | 1997-2005 | 436/37,248 | 431/25,594 | A, F, L, P, S | age, weight, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, renal failure, chest pain, aspirin use, mental illness, alcoholism, lung disease, smoking, total cholesterol |

| Haukka J | 2010 | Finland | cohort | 1996–2005 | 112/2,333 | 135/2,796 | A, C, F, L, P, S | sex, age, follow-up period |

| Hippisley-Cox J | 2010 | England & Wales | cohort | 2002–2008 | NR/225,922 | NR/1,778,770 | A, F, P, R, S | age, sex, comorbidity score, BMI, use of NSAID, smoking, hypertension, use of hormones |

| Jacobs EJ | 2011 | USA | cohort | 1997-2007 | 98/47,814 person-years | 1,184/707,602 person-years | F, L, P, S | age, sex, race, education, smoking, use of NSAIDs, BMI, physical activity, history of elevated cholesterol, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension |

| Vinogradova Y | 2011 | UK | case-control | 1998-2008 | 1,998/10,163 | 7,621/42,415 | A, P, S | diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, BMI, smoking,use of NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and aspirin, hormone replacement therapy, comorbidities, smoking, socioeconomic status |

| Cheng MH | 2012 | Taiwan | case-control | 2005-2008 | 61/297 | 294/1,188 | A, F, L, P, R, S | tuberculosis, diabetes, use of NSAIDs, hormone replacement therapy, other lipid-lowering drugs, number of hospitalizations |

NR = Not Reported; Treated n/N = No. of cases in the treated group, for cohort studies; cases n/N = No. of exposed in the cases, for case–control studies; Statin type: A= Atorvastatin, C = Cerivastatin, F= Fluvastatin, L = Lovastatin, P= Pravastatin, R= Rosuvastatin, S= Simvastatin; ALLHAT-LLT: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial

Table 2. Studies evaluating the association between long-term statin use and risk of total lung cancer.

| Study | year | Study design | RR | 95% CI | Definition of "long-term" statin use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coogan PF | 2007 | case-control | 0.9 | 0.4-2.1 | ≥5 years |

| Khurana V | 2007 | case-control | 0.23 | 0.2-0.26 | >4 years |

| Setoguchi S | 2007 | cohort | 1.02 | 0.59-1.74 | ≥3 years |

| Friedman GD | 2008 | cohort | 1.06 | 0.88-1.28 | >5 years |

| Jacobs EJ | 2011 | cohort | 1.08 | 0.93-1.25 | ≥5 years |

| Vinogradova Y | 2011 | case-control | 1.17 | 0.95-1.45 | ≥6 years |

RR = Relative risk; CI = Confidence interval

Figure 2. Methodological quality of included randomized controlled trials: review authors’ opinion on each item of bias risk based on Cochrane handbook.

“+”, “-” or “?” reflected low risk of bias, high risk of bias and uncertain of bias respectively. ALLHAT-LLT: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial.

Table 3. Methodological quality of included cohort studies and case–control studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

| Case-control studies | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blais L 2000 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Graaf MR 2004 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Kaye JA 2004 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Coogan PF 2007 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Khurana V 2007 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Vinogradova Y 2011 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Cheng MH 2012 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Cohort studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score |

| Friis S 2005 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Sato S 2006 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Setoguchi S 2007 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Friedman GD 2008 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Farwell WR 2008 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Haukka J 2010 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Hippisley-Cox J 2010 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Jacobs EJ 2011 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

Main analysis

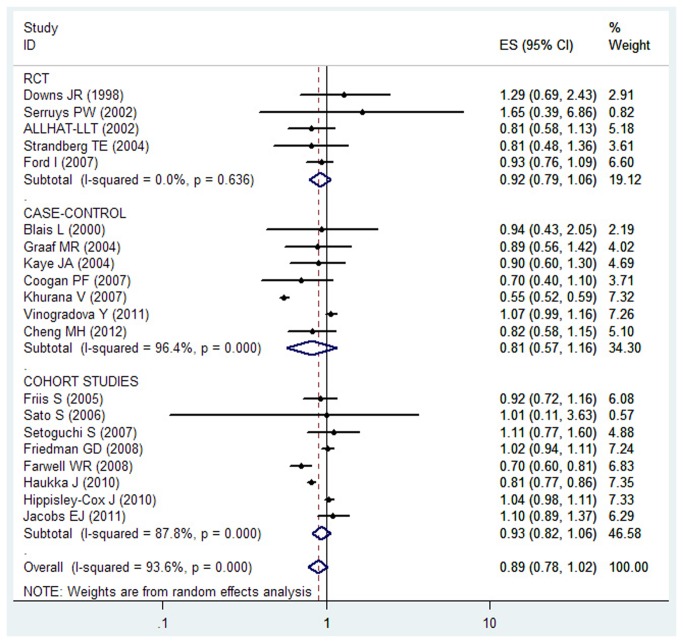

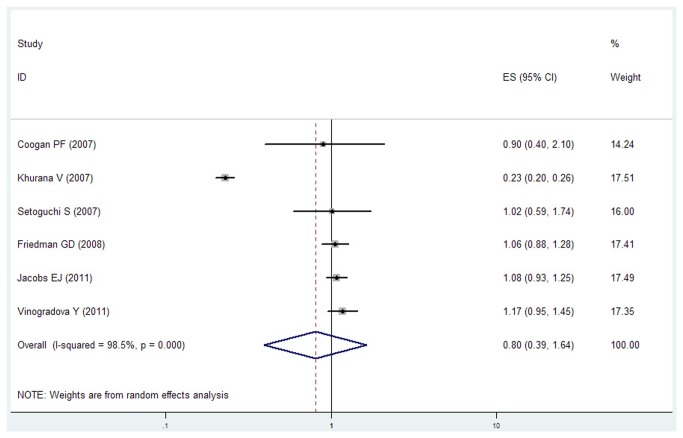

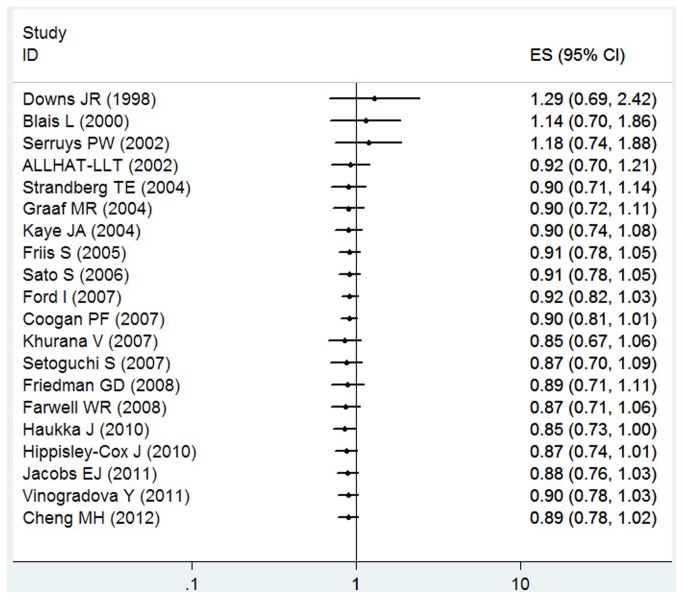

Because of significant heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 93.6%) was observed, a random-effects model was chosen over a fixed-effects model, and we found that statin use did not significantly affect the risk lung cancer (RR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.78, 1.02]). Both multivariable adjusted RR estimates with 95 % CIs of each study and combined RR are shown in Figure 3 . The calculated combined RR for lung cancer in long-term statin use was found to be 0.80 (95% CI [0.39 , 1.64]), presented in Figure 4 .

Figure 3. Forest plot: overall meta-analysis of statin use and lung cancer risk.

Squares indicated study-specific risk estimates (size of square reflects the study-statistical weight, i.e. inverse of variance); horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals; diamond indicates summary relative risk estimate with its corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4. Forest plot: long-term statin use and risk of lung cancer.

Squares indicated study-specific risk estimates (size of square reflects the study-statistical weight, i.e. inverse of variance); horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals; diamond indicates summary relative risk estimate with its corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analysis and cumulative meta-analysis

We found no significant association between statin use and risk of lung cancer among RCTs (RR= 0.92, 95%CI [0.79, 1.06]), cohort studies (RR= 0.93, 95%CI [0.82, 1.06]) as well as case–control studies (RR= 0.81, 95% CI [0.57, 1.16]), presented in Table 4 . When stratified the various studies by study location, no significant association was noted among studies conducted in America (RR= 0.84, 95%CI [0.62, 1.13]), Europe (RR= 0.95, 95%CI [0.82, 1.09]), and Asia (RR= 0.83, 95%CI [0.59, 1.16]). When we examined if thorough adjustment of potential confounders could affect the combined RR, it was observed that studies with higher control for potential confounders (n ≥ 8) as well as studies with lower control (n ≤ 7) presented no significant association (RR = 0.96, 95%CI [0.83, 1.09] and RR = 0.82, 95%CI [0.65, 1.04] , respectively)(Table 4 ). To test the robustness of association and characterize possible sources of statistical heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were carried out by excluding studies one-by-one and analyzing the homogeneity and effect size for all of rest studies. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the study by Khurana V et al.[48] contributed most to the variability among all studies. Moreover, no significant variation was observed in combined RR by excluding any of the studies, confirming the stability of present results. A cumulative meta-analysis of total 20 studies was carried out to evaluate the cumulative effect estimate over time. In 1998, DownS JR et al reported an effect estimate of 1.29 (95% CI [0.69, 2.42]). Between 2000 and 2005, seven studies were published, with a cumulative RR being 0.91 (95% CI [0.78, 1.05]). Between 2006 and 2012, 12 more publications were added cumulatively, resulting in an overall effect estimate of 0.89 (95% CI [0.78, 1.02]) (Figure 5 ).

Table 4. Overall effect estimates for lung cancer and statin use according to study characteristics.

| No. of studies | Pooled estimate |

Tests of heterogeneity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | P value | I2(%) | ||

| All studies | 20 | 0.89 | 0.78-1.02 | <0.001 | 93.60 |

| Study design | |||||

| RCT | 5 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.06 | 0.636 | 0.00 |

| Cohort | 8 | 0.93 | 0.82-1.06 | <0.001 | 87.80 |

| Case–control | 7 | 0.81 | 0.57-1.16 | <0.001 | 96.40 |

| Study population | |||||

| America | 9 | 0.84 | 0.62-1.13 | <0.001 | 96.20 |

| Europe | 9 | 0.95 | 0.82-1.09 | <0.001 | 89.70 |

| Asian | 2 | 0.83 | 0.59-1.16 | 0.819 | 0.00 |

| Adjusted for confounders | |||||

| n ≥ 8 confounders | 7 | 0.96 | 0.83-1.09 | <0.001 | 79.30 |

| n ≤ 7 confounders | 8 | 0.82 | 0.65-1.04 | <0.001 | 95.50 |

| Results for long-term statin use | 6 | 0.80 | 0.39-1.64 | <0.001 | 98.50 |

| Adjustment for smoking | |||||

| Yes | 10 | 0.89 | 0.71-1.11 | <0.001 | 96.90 |

| No | 5 | 0.89 | 0.75-1.06 | 0.958 | 0.00 |

RR = Relative risk; CI = Confidence interval

Figure 5. Forest plot: cumulative meta-analysis of statin use and lung cancer risk.

Publication bias

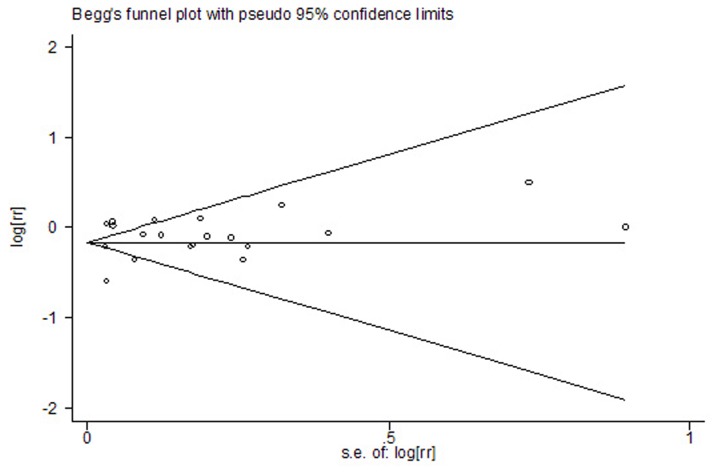

In the present meta-analysis, no publication bias was observed among studies using Begg’s P value (P = 0.56); Egger’s ( P = 0.59) test, which suggested there was no evidence of publication bias (Figure 6 ).

Figure 6. Funnel plot for publication bias in the studies investigating risk for lung cancer associated with use of statins.

No publication bias was observed among studies using Begg’s P value ( P = 0.56) and Egger’s ( P = 0.59) test, which suggested there was no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

In the past decade, the role of statins in the development of cancer has been increasingly understood. The results of meta-analysis conducted by Undela K et al. did not support the hypothesis that statins have a protective effect against breast cancer, however, there was a reduction in risk of breast cancer recurrence in statin users[50]. Consistently, Cui X et al’s meta-analysis suggested that there was no significant association between statin use and pancreatic cancer risk[51]. However, the meta-analysis conducted by Pradelli D et al suggested that statins were inversely related to the risk for liver cancer, with an over 40% decrease in liver cancer risk among statin users, irrespective of the duration of statin exposure[52]. The present meta-analysis included 20 clinical studies currently available (five RCTs, eight cohort studies, and seven case–control studies). Finally, we found no substantial evidence for reduction in lung cancer risk among statin users as compared to non-users, when statins were taken at daily doses for cardiovascular event prevention. In the present meta-analysis, significant heterogeneity was observed among all studies. Therefore, a random-effects model was chosen over a fixed-effects model to determine the pooled RR estimates in our meta-analysis. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the study by Khurana V et al.[48]contributed most to the variability among all studies. The study population in the study of Khurana V et al. consisted solely of veterans with active access to health care and thus they were more likely to be prescribed a statin than the general population. Moreover, an omission of any studies did not significantly alter the magnitude of observed effect, suggesting a stability of our findings. In our subgroup analyses, the results were not substantially affected by study design, study location, and confounder adjustment. RCTs, cohort and case–control studies alone showed no significant association between statin use and risk of lung cancer. Cumulative meta-analysis did not show a significant change in trend of reporting risk of lung cancer in statin users between 1998 and 2012. Furthermore, our results demonstrated that long-term statin use did not significantly reduce the risk of lung cancer incidence. However, we should treat this result with caution. Firstly, patterns of statin use were different in the included studies. In many cases, drug use was irregular, with months of non-use between periods of use. Therefore, cumulative amount of statin defined daily doses (DDDs) could be small despite its long duration. Secondly, the definition of ‘‘long-term use’’ was different among the included studies. Thirdly, only six studies were reported RR estimates of the association between long-term statin use and risk of lung cancer.

Despite some experimental studies have found that statin may induce apoptosis[14–18], inhibit tumor growth[19–22], angiogenesis[23], as well as metastasis[24], our results suggested there was no conclusive preventive effect of statin use on lung cancer risk. These findings were in line with the recent meta-analysis of statin use and overall cancer risk[53]. We should notice that the inhibitory effect of statins on lung cancer cells has thus far been tested only in vitro and may behave differently in vivo. As we know, statins are selectively localized to the liver, and less than 5% of a given dose reaches the systemic circulation. Thereby, the usefulness of statins as chemopreventive agents for lung cancer is doubted given their selective hepatic uptake and low systemic availability[54]. Previous meta-analyses suggested that there was no significant association between statin use and breast and pancreatic cancer risk[50,51], however, statin had a protective effect against liver cancer[52], which supports the opinion above. Further, statins have been shown to increase regulatory T-cell numbers and functionality in vivo[55–57]; both lipophilic and hydrophilic statins decrease natural killer cell cytotoxicity[58]. These immunosuppressive effects of statins might impair host antitumor immune responses, suggesting an opposing effect on tumor development, which should be considered. In one of the included studies[46], Graaf et al presented the effect of duration of statin use and dose. However, neither dose - response nor duration - response relationship was found. The absence of a significant dose-response or duration - response weighs against a causal inference.

The study by Khurana et al[48] found that statin use ≥6 month was associated with a statistically significant risk reduction of lung cancer by 55%(OR = 0.45, 95%CI = 0.42–0.48). We noted that the study population in the study of Khurana et al. consisted solely of veterans with active access to health care and thus they were more likely to be prescribed a statin than the general population. Further, 97.9% of the participants in their study were men. Cheng MH et al[44] investigated the association between statin use and lung cancer risk in female population individually, and they found that statin use was not associated with the risk of female lung cancer. Another study by Hippisley-Cox et al[40] investigated statin use and lung cancer risk among male or female population independently, and the result revealed that statin use was not associated with lung cancer risk in both female(OR =1.00, 95%CI =0.81-1.23) and male population(OR =1.05, 95%CI =0.97-1.13). Therefore, it’s not clear whether statin use was associated with lung cancer risk among male or female population, especially male population. This topic need further discussion in the future when there are enough studies investigating statin use and lung cancer risk among male or female population independently.

The strength of the present analysis lies in inclusion of 20 studies(five RCTs, eight cohort studies, and seven case–control studies). Publication bias, which, due to the tendency of not publishing small studies with null results, was not found in our meta-analysis. Furthermore, our findings were stable and robust in the subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, we did not search for unpublished studies, so only published studies were included in our meta-analysis. Therefore, publication bias may have occurred although no publication bias was indicated from both visualization of the funnel plot and Egger’s test. Second, we haven’t done subgroup meta-analyses of different gender or lung cancer histology, for a lack of original data. Finally, the included studies were different in terms of study design and definitions of drug exposure.

In conclusion, the findings of this meta-analysis, suggested that there was no significant association between statin use and risk of lung cancer. More studies, especially RCTs and high quality cohort studies with larger sample size, well controlled confounding factors and longer duration of follow-up are needed to confirm this association in the future.

Supporting Information

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61: 69-90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. PubMed: 21296855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Cance Stats Cancer worldwide. Available: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/world/. Accessed January 22 2011.

- 3. National Cancer Institute SEER stat fact sheets: Lung and Bronchus. Available: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed January 22 2011.

- 4. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J et al. (2012) The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 380: 581-590. PubMed: 22607822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mills EJ, Rachlis B, Wu P, Devereaux PJ, Arora P et al. (2008) Primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and events with statin treatments: a network meta-analysis involving more than 65,000 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1769-1781. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.039. PubMed: 19022156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newman TB, Hulley SB (1996) Carcinogenicity of lipid-lowering drugs. JAMA 275: 55-60. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.1.55. PubMed: 8531288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keyomarsi K, Sandoval L, Band V, Pardee AB (1991) Synchronization of tumor and normal cells from G1 to multiple cell cycles by lovastatin. Cancer Res 51: 3602-3609. PubMed: 1711413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dimitroulakos J, Marhin WH, Tokunaga J, Irish J, Gullane P et al. (2002) Microarray and biochemical analysis of lovastatin-induced apoptosis of squamous cell carcinomas. Neoplasia 4: 337-346. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900247. PubMed: 12082550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong WW, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, Penn LZ (2002) HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: the statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia 16: 508-519. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402476. PubMed: 11960327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park HJ, Kong D, Iruela-Arispe L, Begley U, Tang D et al. (2002) 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors interfere with angiogenesis by inhibiting the geranylgeranylation of RhoA. Circ Res 91: 143-150. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000028149.15986.4C. PubMed: 12142347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weis M, Heeschen C, Glassford AJ, Cooke JP (2002) Statins have biphasic effects on angiogenesis. Circulation 105: 739-745. doi: 10.1161/hc0602.103393. PubMed: 11839631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alonso DF, Farina HG, Skilton G, Gabri MR, De Lorenzo MS et al. (1998) Reduction of mouse mammary tumor formation and metastasis by lovastatin, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 50: 83-93. doi: 10.1023/A:1006058409974. PubMed: 9802623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kusama T, Mukai M, Iwasaki T, Tatsuta M, Matsumoto Y et al. (2002) 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase inhibitors reduce human pancreatic cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Gastroenterology 122: 308-317. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31093. PubMed: 11832446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Hauff K, Stelmack GL, Schaafsma D et al. (2010) Statin-triggered cell death in primary human lung mesenchymal cells involves p53-PUMA and release of Smac and Omi but not cytochrome c. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803: 452-467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.12.005. PubMed: 20045437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hwang KE, Na KS, Park DS, Choi KH, Kim BR et al. (2011) Apoptotic induction by simvastatin in human lung cancer A549 cells via Akt signaling dependent down-regulation of survivin. Invest New Drugs 29: 945-952. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9450-2. PubMed: 20464445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maksimova E, Yie TA, Rom WN (2008) In vitro mechanisms of lovastatin on lung cancer cell lines as a potential chemopreventive agent. Lung 186: 45-54. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9053-7. PubMed: 18034278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park IH, Kim JY, Choi JY, Han JY (2011) Simvastatin enhances irinotecan-induced apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cells by inhibition of proteasome activity. Invest New Drugs 29: 883-890. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9439-x. PubMed: 20467885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanli T, Liu C, Rashid A, Hopmans SN, Tsiani E et al. (2011) Lovastatin sensitizes lung cancer cells to ionizing radiation: modulation of molecular pathways of radioresistance and tumor suppression. J Thorac Oncol 6: 439-450. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182049d8b. PubMed: 21258249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen J, Hou J, Zhang J, An Y, Zhang X et al. (2012) Atorvastatin synergizes with IFN-γ in treating human non-small cell lung carcinomas via potent inhibition of RhoA activity. Eur J Pharmacol 682: 161-170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.02.015. PubMed: 22510296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanai J, Doro N, Sasaki AT, Kobayashi S, Cantley LC et al. (2012) Inhibition of lung cancer growth: ATP citrate lyase knockdown and statin treatment leads to dual blockade of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways. J Cell Physiol 227: 1709-1720. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22895. PubMed: 21688263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hawk MA, Cesen KT, Siglin JC, Stoner GD, Ruch RJ (1996) Inhibition of lung tumor cell growth in vitro and mouse lung tumor formation by lovastatin. Cancer Lett 109: 217-222. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(96)04465-5. PubMed: 9020924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khanzada UK, Pardo OE, Meier C, Downward J, Seckl MJ et al. (2006) Potent inhibition of small-cell lung cancer cell growth by simvastatin reveals selective functions of Ras isoforms in growth factor signalling. Oncogene 25: 877-887. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209117. PubMed: 16170339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen J, Liu B, Yuan J, Yang J, Zhang J et al. (2012) Atorvastatin reduces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in human non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs) via inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Mol Oncol 6: 62-72. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.11.003. PubMed: 22153388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kidera Y, Tsubaki M, Yamazoe Y, Shoji K, Nakamura H et al. (2010) Reduction of lung metastasis, cell invasion, and adhesion in mouse melanoma by statin-induced blockade of the Rho/Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 29: 127. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-127. PubMed: 20843370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park IH, Kim JY, Jung JI, Han JY (2010) Lovastatin overcomes gefitinib resistance in human non-small cell lung cancer cells with K-Ras mutations. Invest New Drugs 28: 791-799. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9319-4. PubMed: 19760159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8: 336-341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. PubMed: 20171303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327: 557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. PubMed: 12958120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50: 1088-1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. PubMed: 7786990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. PubMed: 9310563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Officers ALLHAT and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group (2002)Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized topravastatin vs usual care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to PreventHeart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA 288: 2998-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR et al. (1998) Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 279: 1615-1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. PubMed: 9613910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ford I, Murray H, Packard CJ, Shepherd J, Macfarlane PW et al. (2007) Long-term follow-up of the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. N Engl J Med 357: 1477-1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065994. PubMed: 17928595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Serruys PW, de Feyter P, Macaya C, Kokott N, Puel J et al. (2002) Fluvastatin for prevention of cardiac events following successful first percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 287: 3215-3222. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3215. PubMed: 12076217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strandberg TE, Pyörälä K, Cook TJ, Wilhelmsen L, Faergeman O et al. (2004) Mortality and incidence of cancer during 10-year follow-up of the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 364: 771-777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16936-5. PubMed: 15337403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farwell WR, Scranton RE, Lawler EV, Lew RA, Brophy MT et al. (2008) The association between statins and cancer incidence in a veterans population. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 134-139. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm286. PubMed: 18182618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Friedman GD, Flick ED, Udaltsova N, Chan J, Quesenberry CP Jr. et al. (2008) Screening statins for possible carcinogenic risk: up to 9 years of follow-up of 361,859 recipients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 17: 27-36. doi: 10.1002/pds.1507. PubMed: 17944002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Friis S, Poulsen AH, Johnsen SP, McLaughlin JK, Fryzek JP et al. (2005) Cancer risk among statin users: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer 114: 643-647. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20758. PubMed: 15578694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haukka J, Sankila R, Klaukka T, Lonnqvist J, Niskanen L et al. (2010) Incidence of cancer and statin usage--record linkage study. Int J Cancer 126: 279-284. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24536. PubMed: 19739258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2010) Unintended effects of statins in men and women in England and Wales: population based cohort study using the QResearch database. BMJ 340: c2197. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2197. PubMed: 20488911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Thun MJ, Gapstur SM (2011) Long-term use of cholesterol-lowering drugs and cancer incidence in a large United States cohort. Cancer Res 71: 1763-1771. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2953. PubMed: 21343395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sato S, Ajiki W, Kobayashi T, Awata N (2006) Pravastatin use and the five-year incidence of cancer in coronary heart disease patients: from the prevention of coronary sclerosis study. J Epidemiol 16: 201-206. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.201. PubMed: 16951539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mogun H, Schneeweiss S (2007) Statins and the risk of lung, breast, and colorectal cancer in the elderly. Circulation 115: 27-33. PubMed: 17179016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blais L, Desgagné A, LeLorier J (2000) 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer: a nested case-control study. Arch Intern Med 160: 2363-2368. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2363. PubMed: 10927735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheng MH, Chiu HF, Ho SC, Yang CY (2012) Statin use and the risk of female lung cancer: a population-based case-control study. Lung Cancer 75: 275-279. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.014. PubMed: 21958449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Strom BL (2007) Statin use and the risk of 10 cancers. Epidemiology 18: 213-219. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000254694.03027.a1. PubMed: 17235211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graaf MR, Beiderbeck AB, Egberts AC, Richel DJ, Guchelaar HJ (2004) The risk of cancer in users of statins. J Clin Oncol 22: 2388-2394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.027. PubMed: 15197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kaye JA, Jick H (2004) Statin use and cancer risk in the General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer 90: 635-637. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601566. PubMed: 14760377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khurana V, Bejjanki HR, Caldito G, Owens MW (2007) Statins reduce the risk of lung cancer in humans: a large case-control study of US veterans. Chest 131: 1282-1288. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0931. PubMed: 17494779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J (2011) Exposure to statins and risk of common cancers: a series of nested case-control studies. BMC Cancer 11: 409. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-409. PubMed: 21943022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Undela K, Srikanth V, Bansal D (2012) Statin use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 135: 261-269. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2154-x. PubMed: 22806241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, Li J, Liao X et al. (2012) Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 23: 1099-1111. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9979-9. PubMed: 22562222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pradelli D, Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Catapano A et al. (2013) Statins and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev, 22: 229–34. PubMed: 23010949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Emberson JR, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Newman C, Reith C et al. (2012) Lack of effect of lowering LDL cholesterol on cancer: meta-analysis of individual data from 175,000 people in 27 randomised trials of statin therapy. PLOS ONE 7: e29849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029849. PubMed: 22276132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hamelin BA, Turgeon J (1998) Hydrophilicity/lipophilicity: relevance for the pharmacology and clinical effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 19: 26-37. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(97)01147-4. PubMed: 9509899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F (2009) The double-edged sword of statin immunomodulation. Int J Cardiol 135: 128-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.023. PubMed: 18485499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee KJ, Moon JY, Choi HK, Kim HO, Hur GY et al. (2010) Immune regulatory effects of simvastatin on regulatory T cell-mediated tumour immune tolerance. Clin Exp Immunol 161: 298-305. PubMed: 20491794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mausner-Fainberg K, Luboshits G, Mor A, Maysel-Auslender S, Rubinstein A et al. (2008) The effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells. Atherosclerosis 197: 829-839. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.031. PubMed: 17826781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Raemer PC, Kohl K, Watzl C (2009) Statins inhibit NK-cell cytotoxicity by interfering with LFA-1-mediated conjugate formation. Eur J Immunol 39: 1456-1465. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838863. PubMed: 19424968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)