Transactional models of development first emerged to better capture complex person-environment processes over time, with a focus on critical bidirectional relations between parents and children that may serve as underlying mechanisms for the development of psychopathology (Sameroff, 1975). Although there has been a recent surge in research on the nature of bidirectional influence during early childhood that explores connections between parent and child psychopathology, little is known about these transactional processes for families of children with known developmental risk. Although longitudinal studies are beginning to emerge, the specific transactional processes among maternal symptomatology, parenting attributes, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms in this population remain largely unexplored (Baker et al., 2003; Hastings, Daley, Burns, & Beck, 2006; Neece, Green, & Baker, 2012).

A considerable amount of research has documented unidirectional relations between parenting and child development. Among such relations, maternal psychological adjustment has long been found to be both a robust predictor of parenting competence (see reviews by Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000) as well as child psychopathology (see reviews by Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Cummings & Davies, 1994). Specifically, maternal symptomatology has been associated with lower levels of sensitivity, low responsiveness, low involvement, more intrusive behavior, more negative emotional expressions, and less positive emotional expressions (Dix & Meunier, 2009, for review; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Additionally, maternal psychological distress is well established as a key risk factor in the development of child behavior problems (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Children of depressed mothers show difficulty with affect regulation and greater risk for both internalizing and externalizing disorders (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Luoma et al., 2001). They also have difficulty controlling their behavior, modulating impulses (Zahn-Waxler, Iannotti, Cummings, & Denham, 1990), and are frequently noncompliant (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1990). Further, current maternal symptomatology may be more influential than prior history (Luoma et al., 2001), and in fact, children of mothers who experience recurrent and chronic depression seem to be most at risk for behavior problems (Ashman, Dawson, & Panagiotides, 2008).

Maternal parenting behavior has been conceptualized as a core mechanism through which psychological distress may affect children, as low levels of maternal sensitivity and harsh parenting practices are strongly associated with children's maladjustment (Rubin & Burgess, 2002) and externalizing problems (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007). According to the differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, 1997), children's temperamental characteristics (i.e. difficult temperament) influence their individual susceptibility to parental rearing practices. For example, in an examination of children's externalizing behavior across ages 2 to 5 years, improvements in behavior were associated with greater maternal sensitivity, but only for children with less difficult temperaments (Mesman et al., 2009), supporting the notion that child characteristics contribute to the nature of maternal influence on children's psychosocial functioning. There are compelling indications that children with difficult temperaments and avoidant or resistant behaviors are harder to effectively parent (Crockenberg & McCluskey, 1986; Mills-Koonce et al., 2007; van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994), and that mothers of children with behavior problems are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, and impaired psychological functioning (Civic & Holt, 2000; Elgar, Curtis, McGrath, Waschbusch, & Stewart, 2003). Indeed, when caregivers report greater stress and emotional distress, more difficult child temperaments are frequently associated with less sensitive parenting behavior (Mertesacker, Bade, Haverkock, & Pauli-Pott, 2004). Yet despite their intuitive appeal, child-related effects are frequently understudied (Crouter & Booth, 2003; Pardini, 2008), and are often more difficult to capture.

Nonetheless, recent evidence from a number of transactional studies support both parent- and child- effects over time (Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Jaccard, 2013; Gross et al., 2009; Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion, & Wilson, 2008b), and several reports document specific parent-child bidirectional effects with maternal symptomology (Gross, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2008a) and parenting behavior (Pardini, Fite, and Burke, 2008). Bagner et al. (2013) reported reciprocal relations between parental depression and child behavior problems (latent variable indicated by internalizing and externalizing symptoms) between ages 4 and 7 years. Gross and colleagues (2008a, 2008b) conducted parallel process and autoregressive analyses between maternal depression and disruptive behavior in boys across middle childhood (ages 5–10 years) and early adolescence (ages 10–15 years), finding that child aggression and maternal depression at 5 years were simultaneously associated with increased maternal depression and increased aggressive behavior one year later, respectively. Bidirectional influences were again found during the transition to adolescence (ages 11–12 years), whereas only parent effects were found between ages 12–15 years. Finally, cross-lagged reciprocal associations have been reported between concurrent maternal depressive symptoms and children's oppositional behavior measured annually for children ages 3 to 6 years, supporting the presence of these critical bidirectional influences earlier in development (Harvey & Metcalfe, 2012).

Evidence also supports bidirectional influences between parenting and child behavior, and such effects are apparent across developmental periods (Gadeyne, Ghesquiere, & Onghena, 2004; Huh, Tristan, Wade, & Stice, 2006; Kandel & Wu, 1995; Pardini et al., 2008). However, child-related effects may be particularly influential during early childhood. Harvey and Metcalfe (2012) found that maternal warmth and children's externalizing behaviors were reciprocally related between ages 3 and 4 years, but at later time points, only parent-effects were noted. Another study reported evidence for child effects on parenting behavior only during early childhood (Verhoeven, Junger, van Aken, Dekovic, & van Aken, 2010). Moreover, in a study of reciprocal relations between infant temperament and maternal depression between 6 and 24 months, only parent effects were found (Hanington, Ramchandani, & Stein, 2010), suggesting that early childhood may represent a sensitive developmental period in which emerging child independence begins to significantly influence parents (Feldman, 2007).

Given evidence for bidirectional effects between parents and children, it is unfortunate that there has not been further investigation of the transactional relations among these three critical facets of early childhood experience: parent symptomatology, child symptomatology, and parenting. Such transactional modeling could identify mechanisms through which parental symptoms, child symptoms, or parental behavior emerge over time, providing a more nuanced understanding of the nature of the early child-parent relationship. There is evidence to suggest that maternal symptoms and/or parenting behavior may mediate the relation between maternal and child symptoms, or parenting and child symptoms (Elgar, Mills, McGrath, Waschbusch, & Brownridge, 2007; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Thus, it is crucial to expand on prior bidirectional research to capture the larger transactional processes that occur during early childhood. However, bidirectional research has been limited by the relative lack of longitudinal designs that capture continuities and discontinuities in developmental attributes of children and parents (Pardini, 2008), and by too little focus on specific conditions under which complex transactional relations are likely to be highlighted. Risk, especially risk that is associated with child characteristics, may enhance within-family transactional processes that influence developmental outcomes (Crnic & Greenberg, 1987) and provides a potentially rich context from which emerging psychopathology may be understood.

Early identified developmental delay presents a unique set of circumstances under which transactional family process may help explain emergent behavior problems in children. Children with early delays have increased risk for developing comorbid externalizing, internalizing, and attention-related behavior problems (Baker et al., 2003; Baker, Neece, Fenning, Crnic, & Blacher, 2010; Dekker et al., 2002, Koskentausta, Iivanainen, & Almqvist, 2007) that are frequently attributed to impairments in regulatory capabilities (Dykens & Hodapp, 2007; Gerstein et al., 2011). In turn, the increased developmental and behavioral risk contributes to increased vulnerability within the family systemsuch that levels of reported symptomatology often appear to be higher in mothers of children with intellectual disabilities in comparison to mothers of typically developing children (Hastings et al., 2006; Olsson & Hwang, 2001).

Beyond the connection between parent and child symptoms, children with developmental delays have increased social, emotional, and behavioral needs that may necessitate the modification of parenting strategies often employed with typically developing children. For example, more directive maternal strategies during interaction with delayed children have been associated with better child behavior and regulation (Marfo, 1990) despite the fact that directiveness is considered less optimal in interactions between typically developing children and their mothers. Still, mothers of children with delays appear generally less sensitive and less warm in their parenting style (Ciciolla, Crnic, & West, 2013; Fenning, Baker, Baker, & Crnic, 2007), characteristics that are associated with increased behavioral problems in this population (Niccols & Feldman, 2006).

Given the potential complexity in the nature of relations among risk, parenting, and child behavior problems during a critical developmental period for emerging competence, as well as the limited research on transactional models, the current study extends prior research by utilizing both mothers and fathers as informants of children's behavior, investigating child internalizing and externalizing symptoms separately to capture potentially distinct processes, exploring the role of maternal symptoms and parenting as mediators of parent-child effects, and investigating the role of developmental risk by comparing these processes in samples of children with and without developmental delay. Although developmental delays are common in early childhood, relatively little research has addressed parenting processes in this population. Thus, the current study employed an autoregressive model with crossover effects to capture transactional influences over and above assessment of factors at previous periods, with a particular focus on families with children at developmental risk. Mediation analyses tested the indirect effects of maternal symptoms and parenting on child behavior. Measurement invariance was used to compare the model between children with and without developmental delay.

This study has four major aims. First, the stability of child internalizing/externalizing symptoms, maternal distress, and maternal sensitivity is examined across child ages 3 to 5 years. Significant associations are anticipated across both the short term annual assessments as well as over the two year period of assessment, indicating the relative stability of constructs over time. Second, bidirectional influences between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms and maternal distress are examined. It was hypothesized that child symptoms at ages 3 and 4 years would predict maternal distress at ages 4 and 5 years, respectively. Likewise, maternal distress symptoms at ages 3 and 4 years would predict child symptoms at ages 4 and 5 years, respectively. Third, the associations between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms and maternal sensitivity are explored, testing maternal distress and maternal sensitivity as possible mediators. It was hypothesized that maternal distress would be directly related to later maternal sensitivity, and that maternal distress would mediate the relation between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms at age 3 years and maternal sensitivity at age 5 years. Further, maternal sensitivity should mediate the relation between maternal distress at age 3 years and child internalizing/externalizing symptoms at age 5 years. Finally, the extent to which developmental delay may moderate these processes was examined, with the expectation that model effects would be stronger for the families of children with developmental delays.

Method

Participants

The participants of the study included families of typically developing children (TD) and children with developmental delays (DD), who were recruited at age 3 from community agencies such as preschools, early intervention programs, and family resource centers in rural central Pennsylvania (25% of the sample) and urban Southern California (75% of the sample) (see Baker, Blacher, Crnic, & Edelbrock, 2002). The study oversampled for children with non-specific, non-syndromal developmental delays, the majority of which involved significant early language and cognitive delays. For inclusion in the TD group, children needed to have a mental development index (MDI) score above 85 on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II (Bayley, 1993). Children were classified with DD if MDI scores were below 75. The MDI scores of a small number of children fell in between 75 and 85 (n = 12). The data for these children were included in the DD sample as there is notable cognitive, academic and social risk for these children, and parents have been reported to be both less positive and less sensitive (Fenning et al., 2007). Analyses were run both with and without these borderline children, with no differences in the overall results. In addition, t-tests comparing the DD group and the borderline group revealed no significant differences. The exclusion criteria included non-ambulation, severe neurological impairment, or a history of abuse.

The study initially screened 260 subjects, all of whom qualified for entry into the study, however, 10 subjects chose not to participate in the study. Thus, the participants included 250 children, 110 of whom were classified as DD. See Table 1 for demographic information and group comparisons. Two-hundred and fifty mothers and 215 fathers participated in the study. Between child age 3 and 5 years, there was a 12.0% attrition rate, with 10.4% of the families dropping out at the 4 year data collection, and 1.6% dropping out at the 5 year collection. Subjects who dropped out of the study did not significantly differ from subjects who remained on any demographic or study variables.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the typically developing and developmentally delayed samples.

| Variables | TD (n = 140) | DD (n = 110) | χ2 (df) | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables | ||||

|

| ||||

| Child gender (% male) | 50.7% | 67.3% | 6.93 (1)** | – |

| Child ethnicitya(% Hispanic) | 8.6% | 26.4% | 20.5 (4)*** | – |

|

| ||||

| Continuous variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | t (df) | Cohen's d |

|

| ||||

| Bayley MDIb | 104.4 (11.7) | 60.0 (12.8) | 28.6 (248)*** | 3.62 |

| Family incomec | 4.8 (1.8) | 3.9 (1.9) | 3.6 (247)*** | .46 |

| Maternal education (years of schooling) | 15.7 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.4) | 4.2 (248)*** | .54 |

| Paternal education (years of schooling) | 15.8 (2.9) | 14.0 (2.7) | 4.7 (228)*** | .62 |

Note. χ2 tests and t-tests compare TD versus DD groups.

Child ethnicity: African American (DD: 3.6%; TD: 11.4%); Asian American (DD: 3.6%; TD: 0.9%); European (DD: 60.7%; TD: 60.0%); Hispanic American (DD: 26.4%; 8.6%); “Other” (DD: 9.7%; TD: 15.7%).

Mental Developmental Index.

Family Income measured on 1 to 7 scale; 1 = $0–$15,000, 4 = $35,001–$50,000, 7 = > $95,001.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Procedure

Laboratory visits took place when children were 3-, 4-, and 5-years old. When children were 3-years-old, trained research assistants informed families of the risks of participating in the study and obtained informed consent from the parents, and verbal assent from the children. They then assessed the mental developmental level of each child, and mothers completed measures of family demographics, parental mental health, and children's behavior.

For the observed laboratory interactions, mothers and their children were presented with three problem-solving tasks that increased in difficulty to offer a range of challenge for the dyad: an easy task that could be quickly solved (fold a paper airplane); a moderately challenging task that was chosen to be at the child's age level (build a Lego® tower); and an extremely difficult task chosen to be well above the child's capability (complete a multi-piece puzzle). Each task was presented to the dyad with basic instructions to try to complete the activity, and mothers were told to let the child attempt to solve the task on their own but then offer any assistance she felt was necessary. The tasks for the DD group were more basic but chosen specifically to be comparable in mental age to the tasks for the TD group. For example, the moderate challenge tower design for the children with DD was less complicated and had fewer blocks. The easy task was not included in the final analyses, as the task rarely took more than a few seconds to solve and required little maternal input, and therefore produced too little interaction data.

Measures

Developmental status

Child developmental status was established with the Mental Development Index (MDI) subscale of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID-II; Bayley, 1993). The BSID-II was standardized on a stratified, random sample representative of the U.S. Census population at the 1988 update (Bayley, 1993; Nellis & Gridley, 1994). Children classified as having developmental delays (DD) scored at least one standard deviation below the mean (MDI < 85). Children with and without DD differed significantly on mean MDI scores, t(248) = 28.59, p < .001, Cohen's d = 3.63 (Table 1).

Child behavior problems

Mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) when the children were 3-, 4-, and 5-years-old. Respondents indicated whether each item was (0) ‘not true', (1) ‘somewhat or sometimes true', or (2) ‘very true or often true' within the past 6 months. Responses were summed and scored on 7 narrow-band factors, 2 broadband factors, and a total problem score. The externalizing and internalizing sum scores were used in all analyses, and father and mother questionnaires were composited in order to have multiple informants of child behavior (composite α range from .79 to .81 on the externalizing subscale, and from .65 to .80 on the internalizing subscale). Between 9% - 12% of mothers and 7% - 9% of fathers rated their children as having T scores in the “borderline” or “clinically significant” range (T score ≥ 65) for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Maternal symptomatology

The Symptom Checklist-35 (SCL-35) is a 35-item short form of the Symptom Checklist-90 and Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1994), used to measure mothers' perceived psychological distress when children were 3, 4, and 5-years-old (coefficient α = .94, .95, and .97, respectively). Mothers rated their level of perceived distress for each item according to a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all and 4 = extremely). The total sum of the ratings was used to provide a measure of perceived distress, with higher scores (range = 0–140) indicating greater distress.

Maternal sensitivity

The laboratory observations at the 3-, 4-, and 5-year visits were coded for Maternal Sensitivity using the Parent-Child Interaction Rating System (PCIRS; Belsky, Crnic, & Gable, 1995). Sensitivity addressed the degree to which the mother's behavior with her child was child-centered. The sensitivity scale measured the extent to which the mother was aware of and appropriately responded to the needs, moods, interests, and capabilities of the child. Markers of sensitivity included acknowledging child's affect; contingent vocalizations by the parent; facilitating the manipulation of an object or child movement; appropriate soothing and attention focusing; evidence of good timing paced to child's interest and arousal level; picking up on the child's interest in toys or games; shared positive affect; encouragement of the child's efforts; and sitting on floor or low seat, at child's level, to interact.

Raters were naïve to group affiliation; however, for some children it was impossible to avoid recognition of developmental delay. Raters were instructed to rate each video individually, taking into account the needs and abilities of each child when assessing the mother's behavior as well as to be aware of the unique experience of each dyad. Sensitivity was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = complete absence of the quality and 5 = strong noticeable presence of the quality). The unweightedkappas (Cohen, 1960) for inter-rater reliability for 30% random samples of videos at the 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year assessment were .76, .68, and .71, respectively.

Results

Data Reduction

The maternal sensitivity variable represented a composite of sensitivity scores from the moderate and difficult problem-solving tasks. Raters coded each task independently according to criteria that implicitly accounted for the level of difficulty. Ratings of maternal sensitivity across the two tasks showed large correlations per Cohen's (1988) norms (at 3 years, r = .594; at 4 years, r = .598; at 5 years, r = .506).

Overview of Analyses

Analyses examined the transactional nature of child behavior problems, maternal distress symptoms, and parenting behavior to determine the direction of influence across time, as well as examine the effect of developmental risk on these relations. Path model analysis in structural equation modeling was conducted using MPlus 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén, 2010) with full information maximum likelihood to account for missing data (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

The overall analysis utilized a three-tiered autoregressive path model with cross-lagged associations among father- and mother-reported child behavior problems, mother-reported distress symptoms, and observed maternal sensitivity. Each construct at age 5 was simultaneously regressed on itself at age 4, and then each construct at age 4 was regressed on itself at age 3, providing a measure of construct stability across time. A large positive stability coefficient indicates that individuals reporting above the mean at time 1 tend to report above the mean at time 2.

Cross-lagged paths from child behavior problems at ages 3 and 4 years to mothers' distress symptoms at 4 and 5 years were estimated, and in turn, from mothers' distress symptoms at ages 3 and 4 years to child behavior problems at 4 and 5 years, respectively. Likewise, respective cross-lagged paths in both directions were estimated between child behavior problems and maternal sensitivity. Finally, paths were estimated from maternal distress symptoms at ages 3 and 4 years to maternal sensitivity at 4 and 5 years, respectively (one direction only because it was not conceptualized that sensitivity would predict maternal distress). Significant cross-lagged paths indicate the temporal direction of effects among child behavior problems, maternal distress symptoms, and maternal sensitivity.

Multiple group analysis using equality constraint was employed to assess the moderating role of developmental risk on the transactional model. Models where all paths were constrained to be equal across groups were compared to models with bidirectional paths between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms allowed to vary across the TD and DD groups. A chi square difference test then indicated whether the unconstrained models fit the data significantly better than the models with constrained paths. When the unconstrained models had significantly better fit to the data than the constrained model, those path coefficients were considered moderated by developmental risk.

Mediation analysis was conducted to examine two models: one that addressed the role of maternal distress (age 4) as a mediator between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms (age 3) and maternal sensitivity (age 5); and one that addressed the role of maternal sensitivity (age 4) as a mediator between maternal distress (age 3) and child internalizing/externalizing symptoms (age 5). The mediation analyses were conducted using MODEL INDIRECT in Mplus with bias corrected bootstrap resampling (5000 samples) for greater accuracy in the estimation of the standard errors (MacKinnon, 2008).

Estimation for adequate model fit was determined according to values of root mean square error of approximation (RSMEA < .05), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < .05), Comparative FitIndex (CFI < .90), and a non-significant chi square statistic (Hooper, Coughlin, & Mullen, 2008).

Preliminary Analyses

Demographic information including comparisons between the TD and DD groups are presented in Table 1. When comparing families of children with DD to families of TD children, children with DD were more likely to be male. Children with DD were also more likely to have families with a lower annual income, mothers with fewer years of education, and fathers with fewer years of education. However, the vast majority of parents had completed a high school degree or obtained at GED (DD: 96.4% of mothers and 89.4% of fathers, TD: 97.9% of mothers and 94.7% of fathers). Child ethnicity significantly differed overall between groups (see Table 1 for breakdown of ethnicity). The groups did not differ by marital status of the mothers, X2(2) = 3.62, p = .16, 84.8% married; age of mother at intake, t(248) = 1.90, p = .059, Mean age = 33.5; or age of father at intake, t(230) = .50, p = .62, Mean age = 36.5. Demographic variables that significantly differed between groups were included as potential covariates in analyses.

Descriptive data for all study variables are presented in Table 2, including t-test comparisons between the TD and DD groups. The results indicated that mothers of children with DD were significantly less sensitive at ages 3 and 5 years. In addition, children with DD were found to have significantly more internalizing and externalizing problems at each age (see also Baker et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics split by developmental status.

| Variables | TD Mean (SD) | DD Mean (SD) | t (df) | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal distress age 3 | 20.9 (19.9) | 24.0 (18.3) | −1.25 (236) | .16 |

| Maternal distress age 4 | 20.3 (19.2) | 25.8 (22.2) | −1.93 (214) | .26 |

| Maternal distress age 5 | 21.9 (18.7) | 26.7 (25.2) | −1.58 (214) | .22 |

| Maternal sensitivity age 3 | 3.3 (0.79) | 2.9 (0.89) | 4.16 (241)* | .54 |

| Maternal sensitivity age 4 | 3.6 (0.83) | 3.4 (0.84) | 1.63 (217) | .22 |

| Maternal sensitivity age 5 | 3.6 (0.75) | 3.3 (0.88) | 3.07 (207)* | .43 |

| Child externalizing age 3 | 12.7 (6.8) | 17.1 (8.4) | −4.49 (242)* | .58 |

| Child externalizing age 4 | 11.5 (6.8) | 16.0 (9.2) | −4.09 (214)* | .56 |

| Child externalizing age 5 | 10.7 (7.6) | 16.0 (9.3) | −4.63 (214)* | .63 |

| Child internalizing age 3 | 7.8 (5.2) | 12.0 (8.0) | −5.00 (242)* | .64 |

| Child internalizing age 4 | 8.2 (5.3) | 11.7 (7.6) | −4.01 (214)* | .55 |

| Child internalizing age 5 | 7.9 (6.0) | 12.1 (8.9) | −4.10 (214)* | .56 |

Note. TD = typically developing group; DD = children with developmental delays.

p < .05.

Correlations among the variables for each group are presented in Table 3. Demographic variables were included in the correlation analyses to determine their relation to other model variables. Results indicated that family income was related to maternal sensitivity and child internalizing behavior at every time point. Child sex was related to maternal sensitivity at 4-years and child externalizing behavior at 3-years. Therefore, these paths were included in the models to control for the effects of family income and child sex.

Table 3.

Summary of intercorrelations.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8 | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Distress (3yr) | − | .70* | .58* | −.12 | −.19* | −.20* | .16 | .18* | .18* | .21* | .23* | .21* | −.15 | .04 |

| 2. Maternal Distress (4yr) | .73* | − | .71* | .01 | −.10 | −.27* | .13 | .18* | .12 | .15 | .16 | .09 | .15 | .13 |

| 3. Maternal Distress (5yr) | .60* | .73* | − | −.02 | −.12 | −.20* | .06 | .10 | .13 | .10 | .11 | .20* | −.10 | .07 |

| 4. Maternal Sensitivity (3yr) | −.06 | .00 | .10 | − | .55* | .25* | −.06 | −.04 | −.08 | −.02 | −.02 | −.06 | .37* | −.11 |

| 5. Maternal Sensitivity (4yr) | −.14 | −.11 | −.05 | .51* | − | .44* | −.10 | −.02 | −.06 | −.05 | .07 | −.04 | .33* | −.03 |

| 6. Maternal Sensitivity (5yr) | −.27* | −.27* | −.13 | .21 | .46* | − | −.05 | .08 | .11 | .04 | .09 | .15 | .17 | −.03 |

| 7. Externalizing Behavior (3yr) | .36* | .52* | .41* | −.13 | −.20 | −.25* | − | .75* | .68* | .57* | .45* | .41* | −.15 | .07 |

| 8. Externalizing Behavior (4yr) | .35* | .50* | .37* | −.05 | −.21* | −.27* | .80* | − | .74* | .50* | .67* | .48* | .12 | −.04 |

| 9. Externalizing Behavior (5yr) | .48* | .48* | .54* | .04 | .06 | −.27* | .70* | .71* | − | .46* | .50* | .71* | −.18* | .04 |

| 10. Internalizing Behavior (3yr) | .31* | .49* | .51* | −.08 | −.19 | −.33* | .65* | .51* | .49* | − | .64* | .53* | −.13 | −.13 |

| 11. Internalizing Behavior (4yr) | .43* | .52* | .50* | .02 | −.19 | −.26* | .58* | .68* | .52* | .75* | − | .64* | −.06 | −.14 |

| 12. Internalizing Behavior (5yr) | .40* | .40* | .50* | .17 | .02 | −.26* | .46* | .44* | .68* | .64* | .68* | − | −.15 | −.06 |

| 13. Family Income | −.19 | −.19 | .05 | .26* | .26* | .26* | .11 | −.06 | −.05 | −.25* | −.31* | −.26* | − | −.18* |

| 14. Child Sex | .10 | .09 | .07 | −.01 | .21* | .11 | .22* | .15 | .06 | .16 | .12 | .01 | .25* | − |

Note. Intercorrelations for the typically developing group are presented above the diagonal (n = 140), and intercorrelations for the group with developmental delays are below the diagonal (n = 98).

p < .05.

Child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, maternal distress, and maternal sensitivity showed high rank-order stability across time as indicated by moderate to large correlations for each variable with itself over time (see Table 3). Small negative correlations were found between maternal sensitivity at age 5 and maternal distress symptoms at ages 3 and 4 in both groups, and also maternal distress symptoms at age 5 in the TD group. In addition, there was a small negative correlation between maternal sensitivity at age 4 and maternal distress at age 3 for the TD group. Moderate positive correlations were found between child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at each time point for both groups. Small correlations in the TD group and small to moderate correlations in the DD groups were found between maternal distress symptoms and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Finally, for the DD group only, there were small negative correlations between maternal sensitivity at age 5 and internalizing and externalizing symptoms at each time point.

Group Comparisons

In comparison to the fully constrained internalizing model, model fit significantly improved when bidirectional paths between child internalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms were allowed to vary across groups, ΔX2 = 11.48 (4), p < .05. Model fit further improved when the within time point correlations and the paths for the control covariates were allowed to vary across groups, ΔX2 = 37.08 (22), p < .05. Additional paths from family income to maternal distress symptoms at ages 3- and 4-years were added post-hoc after inspection of modification indices (M.I.) revealed a large improvement in model fit with the addition of these paths (M.I. > 10). Thus, the final internalizing model included bidirectional paths between child internalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms, the paths for the control covariates, and the within time point correlations that were allowed to vary across groups.

For the externalizing model, model fit did not improve when the bidirectional paths between child externalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms were allowed to vary across groups, ΔX2 = 6.42 (4), n.s., suggesting these paths are not moderated by developmental risk. However, model fit improved when the within time point correlations and the paths for the control covariates were allowed to vary across groups, ΔX2 = 37.14 (20), p < .05. Thus, these paths were allowed to vary in the final externalizing model. Additionally, paths from family income to maternal distress symptoms at ages 3- and 4-years and a correlation between child externalizing behavior at ages 3- and 5-years were added post-hoc after inspection of modification indices (M.I.) revealed large improvements in model fit with the addition of these paths (M.I. > 10).

Final Models

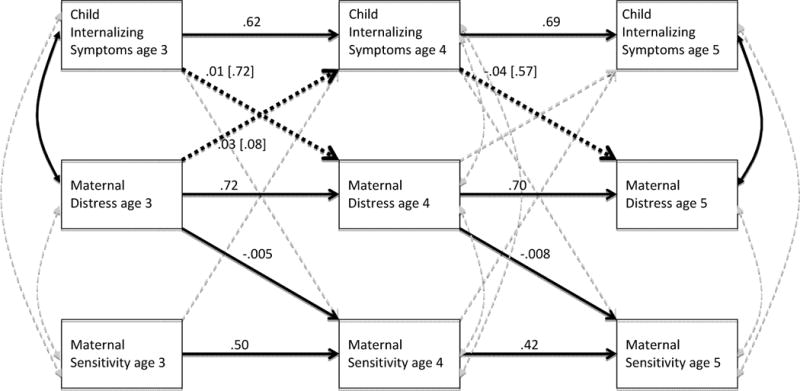

Figure 1 presents the cross-lagged autoregressive internalizing model with unstandardized path coefficients that includes the moderated paths between child internalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms. All primary model path coefficients with confidence limits are presented in Table 4. Intra-time point correlations between the variables were included at each age, and were allowed to vary across the groups. For the control covariates, significant paths were found between family income and maternal sensitivity at age 3 in the TD group, family income and child internalizing at age 3 in the DD group, family income and maternal sensitivity at age 3 in the DD group, family income and maternal distress at age 3 in the DD group, and between child sex and maternal sensitivity at age 4 in the DD group (mothers were more sensitive with boys). The fit indices for the final model for child internalizing symptoms indicated good fit according to accepted standards (Hooper et al., 2008), RMSEA = 0.044, SRMR = 0.061, CFI = 0.98, chi square statistic χ2 = 64.77 (52), n.s. The final model predicted 53% of the variance in maternal symptoms at age 5 for the TD group (51% for DD group), 40% of the variance in child internalizing symptoms at age 5 for the TD group (44% for DD group), and 28% of the variance in maternal sensitivity at age 5 for the TD group (26% for DD group), according to R2 statistics.

Figure 1.

Autoregressive model for child internalizing symptoms, maternal distress, and maternal sensitivity. Child sex and family income were included as covariates but are not shown. Dark, solid lines indicate significant paths. Dark, dotted lines indicate paths moderated by developmental status. Unstandardized path coefficients are reported, and coefficients for the DD group are shown in brackets.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for autoregressive and crossover paths for the internalizing model.

| Parameter | B(SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Construct stability | ||

| Child Internalizing 3 → Child Internalizing 4 | .62 (.05)* | [.52, .71] |

| Child Internalizing 4 → Child Internalizing 5 | .69 (.06)* | [.57, .82] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Maternal Distress 4 | .72 (.05)* | [.61, .82] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Maternal Distress 5 | .70 (.05)* | [.60, .80] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | .50 (.06)* | [.39, .62] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | .42 (.06)* | [.30, .53] |

| Bidirectional paths | ||

| Child Internalizing 3 → Maternal Distress 4 | .01 (.23)/.72 (.20)* | [−.45, .47]/[.06, .34] |

| Child Internalizing 4 → Maternal Distress 5 | −.04 (.22)/.57 (.24)* | [−.48, .40]/[.001, .30] |

| Child Internalizing 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | −.007 (.008) | [−.022, .008] |

| Child Internalizing 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | .004 (.008) | [−.013, .02] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | −.005 (.003)* | [.010, −.001] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | −.008 (.003)* | [−.013, −.003] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Child Internalizing 4 | .03 (.02)/.08 (.03)* | [−.01, .07]/[.023, .13] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Child Internalizing 5 | −.005 (.02)/.03 (.03) | [−.05, .04]/[−.04, .09] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 3 → Child Internalizing 4 | .23 (.38) | [−.51, .97] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 4 → Child Internalizing 5 | .28 (.44) | [−.57, 1.1] |

Note. B = raw path coefficients; SE = standard errors; CI = confidence interval. Path coefficients for covariates and covariance coefficients are not shown. When parameter estimates were freely estimated for TD and DD groups, numbers in italicized font represent the TD group, and numbers in standard and underlined font represent the DD group.

p < .05.

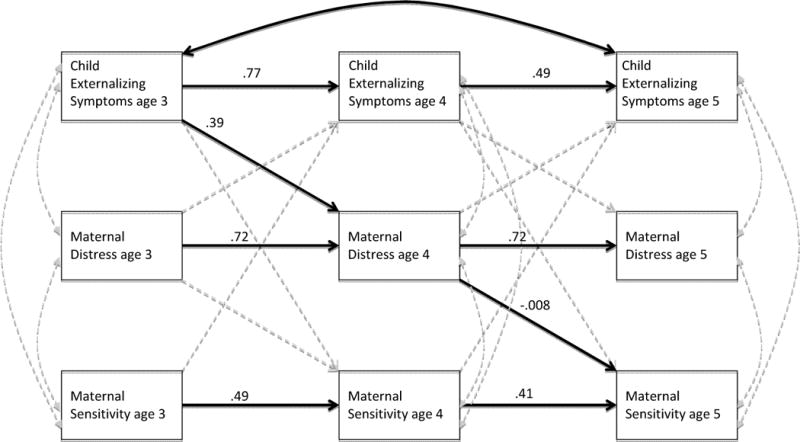

Figure 2 presents the cross-lagged autoregressive externalizing model with unstandardized path coefficients. All primary model path coefficients with confidence limits are presented in Table 5. Intra-time point correlations between the variables were included at each age, as well as a correlation between externalizing symptoms at age 3 and age 5, which were allowed to vary across the groups. For the control covariates, significant paths were found between family income and maternal sensitivity at age 3 in both the TD and DD group, family income and externalizing symptoms at age 3 in the TD group, child sex and child externalizing symptoms at age 3 in the DD group (girls had fewer externalizing symptoms), and child sex and maternal sensitivity at age 4 in the DD group (mothers were again more sensitive with boys). The fit indices for the final model for child externalizing symptoms indicated good fit according to accepted standards (Hooper et al., 2008), RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.061, CFI = 1.00, chi square statistic χ2 = 48.73 (52), n.s. The final model predicted 56% of the variance in maternal symptoms at age 5 for the TD group (42% for DD group), 47% of the variance in child externalizing symptoms at age 5 for the TD group (43% for DD group), and 28% of the variance in maternal sensitivity at age 5 for the TD group (26% for DD group), according to R2 statistics.

Figure 2.

Autoregressive model for child externalizing symptoms, maternal distress, and maternal sensitivity. Child sex and family income were included as covariates but are not shown. Dark, solid lines indicate significant paths. Unstandardized path coefficients are reported.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for autoregressive and crossover paths for the externalizing model.

| Parameter | B(SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Construct stability | ||

| Child Externalizing 3 → Child Externalizing 4 | .77 (.05)* | [.68, .87] |

| Child Externalizing 4 → Child Externalizing 5 | .49 (.10)* | [.26, .69] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Maternal Distress 4 | .72 (.10)* | [.50, .90] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Maternal Distress 5 | .72 (.07)* | [.57, .86] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | .49 (.06)* | [.38, .61] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | .41 (.07)* | [.27, .54] |

| Bidirectional paths | ||

| Child Externalizing 3 → Maternal Distress 4 | .39 (.16)* | [.07, .71] |

| Child Externalizing 4 → Maternal Distress 5 | .02 (.16) | [−.27, .34] |

| Child Externalizing 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | −.009 (.006) | [−.02, .003] |

| Child Externalizing 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | .003 (.007) | [−.01, .02] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Maternal Sensitivity 4 | −.005 (.003) | [−.01, .001] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Maternal Sensitivity 5 | −.008 (.003)* | [−.01, −.002] |

| Maternal Distress 3 → Child Externalizing 4 | .03 (.02) | [−.002, .07] |

| Maternal Distress 4 → Child Externalizing 5 | .03 (.02) | [−.01, .07] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 3 → Child Externalizing 4 | −.09 (.42) | [−.85, .77] |

| Maternal Sensitivity 4 → Child Externalizing 5 | .55 (.46) | [−.38, 1.4] |

Note. B = raw path coefficients; SE = standard errors; CI = confidence interval. Path coefficients for covariates and covariance coefficients are not shown.

p < .05.

Stability of Measurement over Time

The results of the autoregressive analysis indicated construct stability across time. Moderate to large effects (Cohen, 1988) were found for child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, maternal distress symptoms, and maternal sensitivity across child ages 3, 4, and 5 years (see Table 4 and Table 5 for parameter estimates). That is, individuals' levels of child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, maternal distress symptoms, and maternal sensitivity remained stable across time.

Bidirectional Effects

The results of the cross-lagged analysis for the internalizing symptoms model (see Table 4) indicated bidirectional effects between child internalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms from age 3 to 4 years in the DD group only. That is, in families of children with DD, both maternal and child symptoms were found to predict subsequent child internalizing symptoms and maternal symptoms, respectively. From age 4 to 5 years, child internalizing symptoms predicted maternal distress symptoms but the reciprocal association was not found. Moreover, the effects were only found to be true for children with developmental risk. Maternal distress symptoms were found to predict maternal sensitivity from age 3 to 4 years, as well as from age 4 to 5 years. This effect held true for mothers of children with or without developmental risk. Maternal sensitivity was not associated with any other variable other than itself across time. Additionally, child internalizing symptoms were not found to directly predict maternal sensitivity at any time point.

The results of the cross-lagged analysis for the externalizing symptoms model (see Table 5) indicated significant paths from child externalizing symptoms at age 3 to maternal distress symptoms at age 4 years and from maternal distress symptoms at age 4 to maternal sensitivity at age 5. These effects were found for both groups. Maternal sensitivity was not associated with any other variable other than itself across time. Additionally, child externalizing symptoms were not found to directly predict to maternal sensitivity at any time point.

Test for Mediation

The results of the mediation analyses supported the hypothesized indirect effect of child internalizing symptoms on maternal sensitivity via maternal symptoms, ab = −0.006(0.003); z = −2.42, p = .016, 95% CIs [−.011, −0.001]. Due to the moderated path between child internalizing symptoms and maternal distress symptoms, the mediation was only significant for the DD group. The test of the indirect effect of maternal symptoms on child internalizing symptoms via maternal sensitivity was not statistically significant for either group, ab = −0.000(0.002); z = −0.44, p = .96, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.003].

In the externalizing symptoms model, the results of the mediation analyses did not support the hypothesized indirect effect of child internalizing symptoms on maternal sensitivity via maternal symptoms in either group, ab = −0.003(0.002); z = −1.78, p = .086, 95% CI [−0.007, 0.000]. The test of the indirect effect of maternal symptoms on child externalizing symptoms via maternal sensitivity was not statistically significant for either group, ab = 0.022(0.015); z = 1.44, p = .15, 95% CI [−0.008, 0.003].

Discussion

This study investigated the transactional interplay among child internalizing/externalizing symptoms, maternal symptoms, and maternal sensitivity across the preschool period in a sample of children with and without developmental delay. Model fit indices indicated that transactional processes were well reflected in the data. For both groups, more externalizing symptoms at age 3 years was predictive of more maternal distress symptoms a year later, but maternal distress did not have a reciprocal effect on externalizing symptoms, suggesting that difficult or aversive child behavior may play a significant role in affecting the course of maternal psychological symptoms (Gross et al., 2008a, 2008b; Gross et al., 2009), particularly in early childhood. Developmental risk did not alter the nature of these transactional processes for child externalizing symptoms.

The findings for child internalizing symptoms provide evidence for greater reciprocity in relations between maternal distress symptoms and child internalizing symptoms for children with developmental delay. More distress in mothers at child age three was predictive of more child internalizing symptoms a year later, and likewise more child internalizing symptoms at age three was predictive of greater maternal distress a year later. This child effect on maternal distress was also found between ages 4- and 5-years. It is important to note that our measures of maternal distress and child internalizing symptoms captured similar psychological constructs. The greater reciprocity for internalizing symptoms between mothers and children may be related to shared method variance, but it is also suggestive of an intergenerational or genetic etiology that underlies these reciprocal processes. Interestingly, the parent and child effects were only found for children with early developmental risk. It is well documented that children with early developmental delays have significantly greater rates of behavioral and emotional problems, and their families experience greater parenting stress (Baker et al., 2003). However, it is not likely that child internalizing symptoms differentially affect mothers of children with delays, but rather that the additional risk posed by early developmental delay may facilitate greater vulnerability within the mother-child relationship. Indeed, the presence of early developmental delays and child internalizing symptoms may produce a cumulative effect on maternal functioning, creating greater susceptibility to psychological symptoms for these mothers (Olsson & Hwang, 2001).

The bidirectional effects found only between child age 3 and 4 suggests that maternal psychopathology may produce greater influence on children at younger ages, particularly for children at risk for developmental delay. As children develop across this period, environmental factors (preschool, peer relations) may mollify or protect against the effects of maternal symptoms (Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, 2006). In contrast to the current sample in which levels of maternal and child psychopathology were relatively low, the literature on reciprocal effects often addresses high risk samples at greater risk for clinically high levels of depression and child behavior problems (e.g. Gross et al., 2009). Thus, more clinically significant maternal symptoms may produce stronger and more consistent effects over time. Nonetheless, the current findings provide evidence in support of transactional processes connecting maternal distress and children's behavior during the early preschool period (Olsen & Lunkenheimer, 2009).

With respect to reciprocal influence, maternal distress was found to negatively influence maternal behavior across time, even controlling for prior symptoms and sensitivity. Moreover, maternal distress served to mediate the association between child internalizing symptoms and maternal sensitivity, such that greater levels of internalizing symptoms were associated with greater maternal distress, and subsequently lower maternal sensitivity. The current results expand our understanding of the nature of children's influence on their caregiving environment through maternal distress symptoms, and further contribute to the literature on determinants of parenting behavior (Ciciolla et al., 2013). Although prior evidence suggests that parenting behavior such as sensitivity may mediate the effects of parental psychopathology on child functioning (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999), we did not find support for maternal sensitivity as a mediator. Nevertheless, the likelihood of such bidirectional effects is conceptually compelling, and further attention to potential mediators that might explicate such effects between parents and children is merited.

One strength of the current study was the use of multiple measurement modalities and informants, including maternal report of symptoms, father and mother report of child behavior, and observer ratings of maternal behavior. Prior research in this area has been criticized for its reliance on the exclusive use of maternal reports of child behavior and its potential associated bias. It has been suggested that depressed mothers are overly negative in their perceptions of their children's behaviors (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999), and as such, our use of multiple informants and multiple measurement modalities add specific methodological strength to the associations reported. However, it should be noted that there remains the possibility of shared method variance influencing associations between maternal symptoms and child behavior since child behavior was a composite of mother and father reports, and not all fathers participated. An additional strength of the current study included the investigation of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms independently, which provided a more specific understanding of the bidirectional processes between mothers and children. Although children's externalizing behavior was linked with maternal symptoms, there was greater reciprocity for internalizing symptoms, particularly in dyads at greater risk due to the presence of developmental delay. Further, the use of repeated measurements across time expands on our own prior research with this sample. Whereas we have reported that maternal symptoms at child age 3 years were not predictive of maternal sensitivity across the preschool period (Ciciolla et al., 2013), the current findings suggest more time-sensitive relations between maternal psychological symptoms and sensitive parenting behavior in which effects span one year but are not apparent over a full three year period. Repeated, multi-modal measurements across time provide enhanced ability to capture change in the dynamic nature of the parent-child relationship.

The current investigation utilized data on a unique sample of children at early risk for developmental delay, allowing the opportunity to compare these families to families with typically developing children. Given the general lack of research addressing transactional processes in families of children with developmental risk, the current findings provide important descriptive information regarding the complexity of parent- and child-effect processes in development. Contrasting the reciprocal relations between maternal and child psychopathology in these samples offers a nuanced understanding of the role of early developmental delay in affecting the course of maternal psychopathology, and raises questions about whether high-risk children have a stronger influence on maternal well-being than typically- developing children, which may in turn create greater risk for emerging child psychopathology.

One limitation of the current study was that data collection began at age 3, thus excluding consideration of potential earlier influences from the infancy and toddler period. It is likely that both parent- and child-effects begin as early as the perinatal period, and this study provides a somewhat narrower, albeit longitudinal, glimpse into the reciprocal relations between maternal and child psychopathology. Prenatal and early postnatal measurement will be crucial to more fully understanding the unfolding relationship between mothers and children (Brownell & Kopp, 2007). A second limitation is that observed child behavior was not included within the multi-informant method. Additional, external observations of children's behavior might further reduce bias from parent report. Finally, additional mediating variables that may explain the reciprocal relations between maternal and child psychopathology could certainly be entertained. For example, it is possible that more intrusive, hostile parenting may be a better predictor of child behavior problems (see Rubin & Burgess, 2002), whereas maternal sensitivity may be a better predictor of children's prosocial outcomes or parent-child relationship quality. Thus, multiple facets of parental behavior, child behavior, and contextual influence (i.e. family stressors) should be considered as potential factors in future analyses. Findings from the current study are primarily correlational and do not provide causal evidence regarding the occurrence of psychological symptoms or specific parenting behaviors. Further, this study was not sufficiently powered to examine potential gender differences, despite some existing evidence that the bidirectional influence of child and parental symptoms may differ as a function of gender (Crawford, Cohen, Midlarsky, & Brook, 2001; Marchand & Hock, 1998). Subsequent research addressing gender as a moderator could highlight the complex reciprocal processes involved in parent-child relationships.

The results of the current study have important clinical implications regarding the origins of psychopathology as well as prevention and treatment of psychopathology in mothers and young children. First, both maternal psychological symptoms and child behavior problems appear to be highly stable across time, indicating the need for early screening and prevention practices for families with young children (Shaw et al., 2009), especially those at developmental risk. Second, the evidence for bidirectional influences between maternal and child internalizing symptoms suggest an etiological link, and such reciprocal processes may require specific family-centered treatments (Gross et al., 2008a; Dishion & Stormshak, 2006). Certainly there is strong reason to believe that psychopathology may be entrenched in family relationships (Shaw et al., 2009), and the continuity of influence from maternal distress to sensitive parenting during early childhood implicates the importance of maternal psychological symptoms that may interfere with parenting processes and without treatment, may reduce the success of the interventions. In addition, the evidence that maternal distress mediates the relation between child internalizing/externalizing symptoms and maternal sensitivity further strengthens the argument that parental psychopathology should be assessed and treated when addressing issues related to parenting and child behavior.

In summary, maternal psychological symptoms and child internalizing symptoms show a reciprocal pattern of influence during the preschool period that affects the ongoing psychological well-being of mother and child as well as the degree to which mothers behave sensitively. These transactional processes appear particularly salient in the context of developmental risk, further challenging family relationships during a developmental period critical for emerging competencies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by: Grant # HD34879 Awarded by NICHD to K. Crnic (PI), B. Baker, J. Blacher, and C. Edelbrock, co-investigators; NRSA Grant #5-F31-MH869732 Awarded by NIMH to L. Ciciolla (PI).

Contributor Information

Lucia Ciciolla, Email: lcicioll@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Department of Psychology, 950 S McAllister PO Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287.

Emily D. Gerstein, Email: gerstein2@waisman.wisc.edu, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Waisman Center, 1500 Highland Ave, Madison, WI 53705.

Keith A. Crnic, Email: Keith.Crnic@asu.edu, Arizona State University, Department of Psychology, 950 S McAllister PO Box 871104, Tempe, AZ 85287.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman SB, Dawson G, Panagioties H. Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: Relations with child psychophysiology and beahvior and role of contextual risk. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:55–77. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Jaccard J. Disentangling the temporal relationship between parental depressive symptoms and early child behavior problems: A transactional framework. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:78–90. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.715368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, Edelbrock C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2002;107:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, Low C. Pre school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47(4/5):217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Neece CL, Fenning RM, Crnic KA, Blacher J. Mental disorders in five-year-old children with or without developmental delay: Focus on ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Variation in susceptibility to environmental influence: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:182–186. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0803_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Externalizing problems in fifth grade: Relations with productive activity, maternal sensitivity, and harsh parenting from infancy through middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1390–1401. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Kopp CB. Transitions in toddler socioemotional development: Behavior, understanding, and relationships. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ciciolla L, Crnic KA, West SG. Determinants of change in maternal sensitivity: Contributions of context, temperament, and developmental risk. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2013;13:178–195. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2013.756354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civic D, Holt VL. Maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in a nationally representative normal birthweight sample. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TN, Cohen P, Midlarsky E, Brook JS. Internalizing symptoms in adolescents: Gender differences in vulnerability to parental distress and discord. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:95–118. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, McClusky K. Change in maternal behavior during the baby's first year of life. Child Development. 1986;5:746–753. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children's influence on family dynamics: the neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Transactional relationships between perceived family style, risk status, and mother-child interactions in two year olds. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1987;12:343–362. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/12.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Stormshak E. Intervening in children's lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of thirteen regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Hodapp RM. Three steps toward improving the measurement of behavior in behavioral phenotype research. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2007;16(3):617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, Curtis LJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH. Antecedent–consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: A four-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:362–374. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, Mills RSL, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Brownridge DA. Maternal and paternal depressivesymptoms and childmaladjustment: Themediating role of parental behavior. Journal of AbnormalChildPsychology. 2007;35:943–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. Parent-infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing: physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:329–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, Baker JK, Baker BL, Crnic KA. Parenting children with borderline intellectual functioning: A unique risk population. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:107–121. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[107:PCWBIF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadeyne E, Ghesquiere P, Onghena P. Psychosocial functioning of young children with learning problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein ED, Pedersen y Arbona A, Crnic KA, Ryu E, Baker BL, Blacher J. Developmental risk and young children's regulatory strategies: Predicting behavior problems at age five. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011:39, 351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SJ, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Burwell RA, Nagin DS. Transactional processes in child disruptive behavior and maternal depression: A longitudinal study from early childhood to adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:139–156. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL. Reciprocal associations between boys' externalizing problems and mothers' depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008a;36:693–709. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008b;22:742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanington L, Ramchandani P, Stein A. Parental depression and child temperament: Assessing child to parent effects in a longitudinal population study. Infant Behavior and Development. 2010;30:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey EA, Metcalfe LA. The interplay among preschool child and family factors and the development of ODD symptoms. Journal of Child Clinical and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(4):458–470. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C, Beck A. Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, Stice E. Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:185–204. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P. Disentangling mother-child effects in the development of antisocial behavior. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Koskentausta T, Iivanainen M, Almqvist F. Risk factors for psychiatric disturbance in children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Kochanska G. Development of children's noncompliance strategies from toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma I, Tamminen T, Kaukonen P, Laippala P, Puura K, Salmelin R, Almovist F. Longitudinal study of maternal depressive symptoms and child well-being. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1367–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand JF, Hock E. The relation of problem behaviors in preschool children to depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 1998;159:353–366. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfo K. Maternal directiveness in interactions with mentally handicapped children: An analytical comparison. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31:531–549. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertesacker B, Bade U, Haverkock A, Pauli-Pott U. Predicting maternal reactivity/sensitivity: The role of infant emotionality, maternal depressiveness/anxiety, and social support. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Stoel R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Koot HM, Alink LRA. Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalizing problems: Differential susceptibility of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Child Abnormal Psychology. 2009;37:625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills-Koonce WR, Gariépy JL, Propper C, Sutton K, Calkins S, Moore G, et al. Infant and parent factors associated with early maternal sensitivity: A caregiver-attachment systems approach. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellis L, Gridley BE. Review of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-Second Edition. Journal of School Psychology. 1994;32:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(94)90011-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niccols A, Feldman M. Maternal sensitivity and behaviour problems in young children with developmental delay. Infant and Child Development. 2006;15:543–554. doi: 10.1002/icd.468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson MB, Hwang CP. Depression in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2001;45:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SL, Lunkenheimer ES. Expanding concepts of self-regulation to social relationships: Transactional processes in the development of early behavioral adjustment. In: Sameroff A, editor. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 55–76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA. Novel insights into longstanding theories of bidirectional parent-child influences: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Fite PJ, Burke JD. Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and African-American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:647–662. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess K. Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting. 2. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 383–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. Transactional models in early social relations. Human Development. 1975;18:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella SV. Implications of timing of maternal depressive symptoms for early cognitive and language development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:65–83. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC, Hoeksma JB. The effect of infant irritability on mother-infant interaction: A growth-curve analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven M, Junger M, van Aken C, Dekovic M, van Aken MAg. Parenting and children's externalizing behavior: Bidirectionality during toddlerhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Ionnotti RJ, Cummings EM, Denham S. Antecedents of problem behavior in children of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]