Abstract

Purpose: Ultrasound can be used to noninvasively produce different bioeffects via viscous heating, acoustic cavitation, or their combination, and these effects can be exploited to develop a wide range of therapies for cancer and other disorders. In order to accurately localize and control these different effects, imaging methods are desired that can map both temperature changes and cavitation activity. To address these needs, the authors integrated an ultrasound imaging array into an MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) system to simultaneously visualize thermal and mechanical effects via passive acoustic mapping (PAM) and MR temperature imaging (MRTI), respectively.

Methods: The system was tested with an MRgFUS system developed for transcranial sonication for brain tumor ablation in experiments with a tissue mimicking phantom and a phantom-filled ex vivo macaque skull. In experiments on cavitation-enhanced heating, 10 s continuous wave sonications were applied at increasing power levels (30–110 W) until broadband acoustic emissions (a signature for inertial cavitation) were evident. The presence or lack of signal in the PAM, as well as its magnitude and location, were compared to the focal heating in the MRTI. Additional experiments compared PAM with standard B-mode ultrasound imaging and tested the feasibility of the system to map cavitation activity produced during low-power (5 W) burst sonications in a channel filled with a microbubble ultrasound contrast agent.

Results: When inertial cavitation was evident, localized activity was present in PAM and a marked increase in heating was observed in MRTI. The location of the cavitation activity and heating agreed on average after registration of the two imaging modalities; the distance between the maximum cavitation activity and focal heating was −3.4 ± 2.1 mm and −0.1 ± 3.3 mm in the axial and transverse ultrasound array directions, respectively. Distortions and other MRI issues introduced small uncertainties in the PAM/MRTI registration. Although there was substantial variation, a nonlinear relationship between the average intensity of the cavitation maps, which was relatively constant during sonication, and the peak temperature rise was evident. A fit to the data to an exponential had a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.62. The system was also found to be capable of visualizing cavitation activity with B-mode imaging and of passively mapping cavitation activity transcranially during cavitation-enhanced heating and during low-power sonication with an ultrasound contrast agent.

Conclusions: The authors have demonstrated the feasibility of integrating an ultrasound imaging array into an MRgFUS system to simultaneously map localized cavitation activity and temperature. The authors anticipate that this integrated approach can be utilized to develop controllers for cavitation-enhanced ablation and facilitate the optimization and development of this and other ultrasound therapies. The integrated system may also provide a useful tool to study the bioeffects of acoustic cavitation.

Keywords: image guided FUS, cavitation mapping, MR thermometry, cavitation enhanced ablation

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound energy can be noninvasively focused deep into soft tissue and can produce a range of bioeffects arising from thermal and nonthermal mechanisms. Harnessing these effects holds great promise to treat cancer and other diseases. Thermal effects (i.e., viscous heating), obtained by highly focused, high power, continuous wave exposures (>1 s), have successfully been employed for high-temperature ablation of tumors or other dysfunctional tissues1, 2 and, at lower temperatures, to induce mild hyperthermia for radiosensitization,3, 4 drug release,5, 6, 7 and other treatments.8 Mechanical effects are predominately associated with acoustic cavitation—stable and/or inertial oscillations of microbubbles in the ultrasound field. These microbubbles can either be nucleated by high-intensity, pulsed wave excitations or introduced by injecting agents such as stabilized microbubbles originally used as ultrasound contrast agents. A number of therapies that exploit acoustic cavitation have been investigated. Cavitation nucleated during short, high-intensity bursts has been employed for tissue liquefaction9 and blood clot dissolution.10, 11 Lower intensity sonications applied after injection of microbubbles or other sonosensitive agents can be used to permeabilize vascular or cellular barriers for drug delivery12, 13, 14or other treatments.15, 16, 17 Approaches that combine the thermal and mechanical effects of focused ultrasound (FUS), such as cavitation-enhanced ablation, are also under investigation.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

To selectively promote and sustain the desired effects, one typically selects an appropriate set of acoustic parameters (i.e., frequency, burst length, pulse repetition frequency) and then tunes the amplitude to achieve the desired temperature rise or level of cavitation activity. While one can generally know the acoustic pressure amplitude or intensity in vitro with high accuracy, it can be extremely challenging in vivo due to uncertainties in the acoustic, thermal, and vascular properties of the tissues along the ultrasound beam path. One also needs to ensure that the FUS beam is correctly localized and that unwanted effects do not occur at nontargeted regions. To obtain safe and efficacious FUS treatments and, more importantly, to enable their widespread clinical translation, precise spatiotemporal assessment of FUS-induced heating and cavitation activity during the treatment is critical.

Currently, the only widely available method for quantitative mapping of temperature changes in vivo uses MRI and the temperature sensitivity of the proton resonant frequency (PRF) of water,24 which is linear over the range of temperatures used for FUS thermal therapies and is independent of tissue type and thermal history.25, 26 Typically, one estimates changes in PRF using phase maps of a gradient echo sequence27 referenced to either a preheating image or to surrounding tissue regions that are assumed to be unheated.28 While MR temperature imaging (MRTI) has limitations (low spatiotemporal resolution, insensitivity in fat, for example), it enables one to have closed-loop control over FUS thermal therapies to ensure that the induced heating is accurately targeted and reaches the desired thermal dose.29 Clinical MRI-guided FUS (MRgFUS) systems that utilize MRTI have been developed and are currently approved or are being investigated for thermal ablation in numerous targets.30 These systems also exploit MRI's superior soft tissue contrast and ability to image in any orientation, which are useful for treatment planning and evaluation of the treatment outcome. However, no MRI-based methods are currently available for monitoring or controlling acoustic cavitation.

Cavitation has typically been monitored in vivo by monitoring the acoustic emissions produced by microbubble activity within the FUS beam using one or a few single-element piezoelectric transducers operating in passive mode (passive cavitation detector—PCD).31 The frequency content of the emissions recorded by a PCD is used to identify the presence of cavitation and infer the mode of microbubble oscillation.32, 33 Strong emissions at harmonics of the FUS frequency, as well as sub- and ultraharmonic emissions, are generally associated with the presence of stable cavitation; broadband emissions are associated with inertial cavitation and microbubble collapse. Good correlations have been extracted between the spectral content of the acoustic emissions and specific bioeffects of acoustic cavitation both in vitro and in vivo.16, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Currently, clinical MRgFUS systems utilize PCD's to avoid any significant cavitation activity during thermal ablation—the presence of large subharmonic or broadband emissions alerts the operator to reduce the acoustic power level.

If MRgFUS is to be used for therapies that utilize acoustic cavitation, it would be essential to not only detect the presence of microbubble activity, but to map its location and strength. To this end, active9, 13 and passive21, 22, 39, 40 ultrasound imaging methods (or a combination of both41, 42) using an array of piezoelectric elements have been investigated. Active ultrasound imaging (i.e., B-mode imaging) is used to confirm cavitation and/or boiling during FUS ablation guided by ultrasound imaging.43, 44 Current passive methods produce images with a lower spatial resolution than active methods, but they have some advantages. For example, they directly map microbubble emissions instead of attempting to map reflections of microbubbles in the FUS field, which may be challenging for small or transient bubbles.41 The passive techniques can also be used synchronously with the treatment, do not interfere with it,39 and can be used to isolate specific modes of oscillation.22, 45 They also have potential advantages when sonicating behind highly aberrating media such as the skull,46 because the diverging pressure wave originating from oscillating microbubbles only passes once through the aberrating media.

The aim of the present study was to integrate an ultrasound imaging system into an MRgFUS device to provide comprehensive image guidance that can simultaneously display temperature elevation using MRTI and microbubble activity using passive acoustic mapping (PAM). We tested the combined system with sonications that induced cavitation enhanced heating in a tissue-mimicking FUS/MRI phantom, which also provided the ability to extract correlates between temperature rise and acoustic emissions by cavitation activity. As the MRgFUS system we utilized was designed for high-intensity transcranial sonication in the brain47 these experiments were also performed in a phantom-filled ex vivo nonhuman primate skull. We also tested the feasibility of mapping cavitation activity during low-intensity burst sonications on a mock vessel in the skull phantom filled with an ultrasound contrast agent. Prior to the sonications, images of fiducial markers that were visible in both MRI and B-mode ultrasound imaging were collected and used to determine the transformation matrix that registered the images from the two modalities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MRTI

The temperature sensitivity of the PRF in water, which varies at a rate of about −0.01 ppm/°C, arises from heat-induced changes in hydrogen bonds and consequent changes in electron screening of the hydrogen nucleus.24 These changes, which modify the magnetic field at the nucleus, result in a shift in PRF through the Larmor relationship. The PRF can be readily estimated from the phase maps obtained from a gradient echo MRI sequence by dividing the phase by 2π times the TE interval, which is the time the phase develops during the image acquisition.27 Due to magnetic field inhomogeneities that cause spatial variations in PRF unrelated to heating, only temperature changes can be estimated with this method. The relationship between changes in temperature (ΔT) and changes in phase (Δϕ) is given by the following equation:

| (1) |

where γ/2π is the gyromagnetic ratio (42.58 MHz/tesla), B0 is the flux density of the main magnetic field, α is the temperature dependence of the electron screening constant (−0.01 ppm/°C), and TE is the echo time in seconds.

Passive acoustic mapping

Passive acoustic mapping (PAM) (Refs. 40, 39, 41, and 46) is based on the passive imaging problem developed previously for mapping the locations of underground acoustic sources.48, 49 This method uses a number of transducer elements to synchronously record the diverging pressure waves produced by one or more microbubbles oscillating in an acoustic field. The wave emitted from each bubble can be modeled as being produced by a point source s(r, t) originating from position r(x, y, z). By making some simple assumptions, we can locate this point source using the pressure recorded at the locations rn of the N transducer elements. Assuming a constant sound speed c between the bubble and the transducer and ignoring attenuation, the location of the point source can be estimated by coherently summing the recorded acoustic emissions u(rn, t) in (r, t) space, with . Then, reconstruction of the relative point source intensity can be estimated via back-propagation:

| (2) |

where |r − rn| describes geometric wavefront loss. An image is formed by repeating this procedure at multiple coordinates. As noted by Norton and Won,49 this reconstruction produces a bias that can be corrected by subtracting the incoherent background noise (i.e., the DC component). The relative point source intensity is then given as follows:

| (3) |

The modified recorded wavefront signifies a filtered version of u(rn, t): with * denoting convolution. In the present study, a 0.9 MHz high pass Butterworth filter was used (see below).

For the linear array used in this study, the three-dimensional vectors r are converted to image coordinates x (transverse) and z (axial) (y = 0). The image amplitude is proportional to the time-averaged intensity (i.e., the energy of the pressure wave) of the acoustic emissions originating from the microbubbles. Recording of the received signal over a longer time39 improves the frequency resolution, allowing for more accurate characterization of the mode of microbubble oscillations, and improving the SNR for heavily attenuated acoustic emissions (i.e., skull). This will be at the cost of longer reconstruction times.

To remove the sensitivity profile of the transducers and reconstruction algorithm artifacts the maps were normalized to a reference map collected at a power just below the cavitation threshold and converted to dB using the following equation:

| (4) |

To take into account the different sound speeds in the water and in different tissues in the imaging plane (Fig. 1), the average speed of sound between each point in the image and the imaging transducer can be determined according to the following equation:

| (5) |

where di and ci are the thickness and sound speed, respectively, of the M different media in the beam path (i.e., tissue, skull, water, etc,), and L is the total propagation distance. Here, in the back-projection [Eq. 2], the average speed of sound from the geometrical focus of the FUS to the array was used for each point in the cavitation map.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. (Left) Diagram (approximately to scale) showing arrangement of the quality assurance phantom, ultrasound imaging array, and MRI coil within the 30 cm diameter hemisphere transducer of the MRgFUS system. A brass reflector oriented at 45° to the face of the imaging array directed the ultrasound imaging plane parallel to the focal plane of the MRgFUS device. The imaging array was connected to a research ultrasound imaging engine located outside of the MRI room. The face of the imaging array was 13 cm away from the geometric focus of the MRgFUS system—a distance selected to accommodate a human head in future works. (Right) Sagittal and axial MRI of a phantom-filled ex vivo macaque skull. In this example, a channel in the phantom was created for experiments sonicating an ultrasound contrast agent.

Apparatus for simultaneous ultrasound and MR imaging

The experimental apparatus consisted of a clinical prototype MRgFUS system developed for transcranial thermal ablation in the brain (ExAblate 4000, InSightec, Haifa, Israel) and a linear ultrasound array that was connected to a research ultrasound imaging engine (Verasonics Inc, Redmond, WA) through the MRI penetration panel. Sonications were performed in a tissue-mimicking phantom and in a phantom-filled macaque skull. The phantom or skull was mounted so it was centered on the geometrical focus of the MRgFUS device (Fig. 1). For most experiments, the data collection from the two modalities was synchronized using a trigger supplied by the MRI system during its RF excitation.

The MRgFUS system was comprised of a hemispheric 1024-channel phased array (diameter: 30 cm; frequency: 220 kHz), a 1024-channel driving system, a water degassing/circulation system, and a user console. It was integrated with a clinical 3T MRI (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). In these experiments, the transducer was facing upwards (i.e., rotated 90° from its normal clinical use) and filled with degassed water like a bowl. MR imaging was performed using a 14 cm diameter receive-only surface coil (constructed in-house). The phased array was used to steer the focal point to different targets. It is usually also employed for aberration correction when sonicating transcranially. Such correction is not needed to focus through the thin macaque skull,50 and it was not used in these experiments.

The ultrasound imaging probe was a commercially available, 128-element (82 mm) linear array (L382, Acuson, Seattle) with a center frequency of 3.21 MHz and a bandwidth of approximately 75%. For these experiments, 64 elements that spanned the entire array (every second element) were used. The array was incorporated into the hemispheric FUS array with 6 mm thick brass plate, with dimensions 30 × 100 mm, that served as an acoustic mirror. The mirror was placed at a 45° angle with respect to the face of the imaging array, which enabled the collection of ultrasound images in the focal plane of the MRgFUS device without having to insert the entire imaging array into the FUS beam path (Fig. 1). Using this mirror reduced the profile of the imaging array within the hemisphere array and avoided high-intensity sonication directly on it. The presence of this mirror blocked less than 2% of the FUS beam. After confirming that the imaging array was not ferromagnetic, it was mounted in the MRgFUS system. A ∼10 m extension cable (assembled in house) was used to connect the array's cable (2 m long) to the MRI room's penetration panel via “DL” connectors. An additional extension cable (assembled in house) connected the ultrasound imaging engine to the penetration panel outside the MRI room. No additional circuitry (amplification, filtration, impedance matching, etc.), was used. The raw RF data from each element were read synchronously; no beam-forming was performed. The system was controlled using software written in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Experimental protocol and sonications

Phantom

Sonications were performed in two FUS/MRI phantoms. The first was a quality assurance phantom (ATS Laboratories, Bridgeport, CT) provided by the vendor of the MRgFUS system. It was approximately cylindrical (radius: 4 cm; height: 15 cm) and was partially immersed to a depth 5–6 cm below the water surface (Fig. 1). The second was prepared in-house and was used to fill an ex vivo rhesus macaque skull. A proprietary recipe consisting of degassed water, milk powder (with fat content less than 1%), and additional preserving materials was used.51 The phantom had a sound speed of 1625 m/s and an attenuation coefficient of 5.3 Np/m/MHz (Table 1). This phantom recipe was selected since it had similar acoustic properties as brain tissue, which has a reported attenuation coefficient and sound speed of approximately 5 Np/m/MHz and 1600 m/s, respectively.52 The rhesus macaque skull was submerged in deionized water and degassed in a vacuum chamber for one day. Then it was filled with freshly prepared phantom while it was in a liquid state. The phantom set overnight in a cold room and excess material was removed from the outer surface. The skull was completely filled and stored in degassed water between experiments at 4 °C.

Table 1.

The speed of sound (SOS) and thickness of the different media between the focal region of the MRgFUS device and the ultrasound imaging probe.

| Material | Thickness (mm) | SOS (m/s) | Absorption at 1 MHz (Np m−1) | Mean SOS (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality assurance phantom | Phantom | 40 | 1528 | 53 (Ref. 64) | 1494 |

| Water | 90 | 1480 (at 19 °C) | 2.88 × 10−4 (Ref. 65) | ||

| Brain-mimicking phantom | Phantom | 32 | 1625 | 5.3 (attenuation) (Ref. 51) | 1552 |

| Skull | 3 | 3080 | 17.3–234.5 (Ref. 66) | ||

| Water | 95 | 1480 (at 19 °C) | 2.88 × 10−4 (Ref. 65) |

In most experiments, sonications were performed in the phantoms to produce cavitation-enhanced heating. An experiment was also performed to test the feasibility of PAM during low-power sonications combined with an ultrasound contrast agent. For this experiment, a narrow channel (inner diameter: about 1.8 mm) was placed into the phantom material during the phantom formation process. It was filled with either saline or 1000× diluted Definity (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc, MA). In all of the experiments, the average speed of sound for the media between the imaging probe and the targets for the two experiments was determined according to Eq. 5 using the values shown in Table 1. During all experiments, the water was at room temperature (18–20 °C).

Sonications

In each cavitation-enhanced heating experiment, the focus was steered to one to five locations in the phantom in the imaging plane of ultrasound imaging array. For cavitation-enhanced heating, each location was sonicated for 10 s at increasing acoustic power levels (20–130 W) until broadband acoustic emissions were detected, indicating that the cavitation threshold was reached. After the onset of inertial cavitation additional sonications were performed at that power level. The different targets were spaced approximately 2 cm apart and were located within a few centimeters from the geometric focus of the MRgFUS device, which was 13 cm away from face of the ultrasound imaging array. Overall, we analyzed sonications at nine and three locations in the quality assurance phantom and the phantom-filled skull, respectively. One of the locations in the experiments with the ex vivo skull were performed with the ultrasound contrast agent; two sonications were performed at this location.

MR temperature imaging

During cavitation-enhanced heating, the sonications were monitored with MRTI in the same plane used for PAM. A fast-spoiled gradient sequence with the following parameters was used: TR/TE: 29.2/13.5 ms; flip angle: 30°; field of view: 20 cm; slice thickness: 3 mm, image matrix (frequency × phase encoding directions): 256 × 128; receive bandwidth: ± 5.7 kHz; scan time: 3.9 s. These parameters were selected to be similar to those used during clinical transcranial MRgFUS.53 Four presonication images were acquired and averaged to improve SNR, and another eight images were acquired during and after sonication in order to map temperature changes in the targeted area as a function of time.

With the low receiver bandwidth utilized here to maximize SNR in the MRTI, image distortions of a few millimeters, primarily in the frequency encoding direction, occur due to magnetic field inhomogeneities within the MRgFUS device. Due to an artifact that appeared when the phase encoding direction was in the left/right direction [see below, Fig. 7a], the frequency encoding direction in MRTI was oriented in a direction that corresponded to the axial direction in the ultrasound imaging in most cases. The low bandwidth employed here also caused an additional artifact when the focal heating induced a PRF shift that exceeded the receive bandwidth per voxel (44.5 Hz/voxel). When the temperature rise exceeded 34.8 °C (assuming a temperature dependence of −0.01 ppm/°C), the signal in the heated region was shifted by an entire voxel, leaving a signal void at the previous location. A rapid temperature rise can also cause phase-wrapping in MRTI, which will also cause a signal void. When comparing the temperature rise to the cavitation activity, measurements were excluded when there was a signal void in the heated area. Heating was distinguished from noise and other artifacts by examining the time course of the signal in MRTI; voxels where the apparent temperature changed randomly over time were assumed to be noise or other artifacts.

Figure 7.

Transcranial PAM and MRTI acquired simultaneously during cavitation-enhanced heating in a phantom-filled ex vivo macaque skull. (a) MRTI, cavitation maps, and the fusion of the two modalities obtained during two successive 100 W sonications at different locations. Note that cavitation activity at the location of the first sonication target is evident in PAM acquired during the second sonication. This activity was not observed in MRTI. Cavitation activity and heating were also observed in a location near the skull during the first sonication (dashed yellow circle). Other voxels that appeared to be heated in the MRTI were noise resulting from low signal magnitude (such as in the skull) or other artifacts; temperature vs time plots of those voxels were random and clearly not heating. The phase- and frequency-encoding directions in the MRTI were swapped between sonications at targets 1 and 2. The large artifact evident at the bottom of the MRTI for target 2 (white arrow) appeared when the phase-encoding direction was oriented left/right. Swapping phase- and frequency-encoding also introduced distortions and apparent shifts in the image; note the apparent change in position of the skull between targets 1 and 2 (white dashed line). (b) The average temperature rise in a 3 × 3 voxel region around the focal spot and the respective acoustic emissions for the two sonicated targets. For the acoustic emissions, the average power spectra are shown.

Passive acoustic mapping

For PAM, typically 40 RF waveforms were recorded by the ultrasound imaging engine (in some experiments we collected 50 RF waveforms) at a 5 Hz frame rate during each sonication. Each waveform had 180 μs of data acquired at a 12.84 MHz sampling rate (i.e., four times the 3.21 MHz central frequency). During the sonications, the RF data for each transducer element was used to measure the power spectrum of the acoustic emissions, and their averaged spectrum was displayed in real-time. Cavitation maps were generated offline on the same computer. The data were filtered with a 0.9 MHz high-pass Butterworth filter to reduce contributions from the transmitting FUS device and first three harmonics that could be generated due to nonlinear sound propagation. After filtration the cavitation maps were formed. It took a few milliseconds to record the acquired data to memory and to display the spectra. The processing time to reconstruct a passive map with a 90 mm × 80 matrix and a 0.5 mm pixel size was approximately 100 s using a 64-bit personal computer with two 3.53 GHz quad-core processors (Precision T7500, Dell). We did not attempt to optimize this processing in this study. The location of the maximum activity was found in every passive acoustic map obtained during each sonication. Images shown below are the average of these maps (typically an average of 40 individual maps acquired over 8 s), unless otherwise noted.

To avoid interference in the ultrasound imaging during MRI acquisition, the acoustic emissions were recorded when the imaging gradients were inactive. This was achieved for the sequence used here for MRTI by adding a 5 ms delay to a trigger produced by the MRI system during its RF excitation using an arbitrary waveform generator (33220A, Agilent Technologies). In experiments that tested low-power burst sonications (burst length: 10 ms) and an ultrasound contrast agent, this waveform generator was used to gate the FUS device and to trigger the ultrasound imaging engine; 40 waveforms were acquired at a rate of 1 Hz during each sonication. MRI was not acquired during sonication in that experiment since no measurable heating was produced at the low powers used.

Before the sonications, MRI and B-mode ultrasound imaging of fiducial markers were used to determine the transformation matrix between the two imaging coordinate systems. The fiducial markers used (MR-Spots, Beekley Medical) were plastic capsules (dimensions: radius: 7 mm and length: 17 mm) filled with an MRI-visible liquid that were also visible in ultrasound imaging. Three fiducial markers were attached to a plate, which was mounted just above the plane of the ultrasound imaging probe.54

DATA ANALYSIS

The ultrasound imaging and MRI data were analyzed using Matlab. For each sonication, the voxel in each acoustic map with the maximum intensity was found and the maximum intensity recorded. To avoid erroneous detection of cavitation activity from previously sonicated targets (see below), we searched within in a 30 × 10 mm ROI centered on the expected focal region. Their locations of maximum intensity were compared to locations of the center of the heating zones evident in MRTI. Data with no detectable acoustic activity (intensity in PAM less than 1.5 dB) were excluded from this analysis. The relationship between the maximum intensity in the averaged cavitation maps (in dB) and peak temperature rise was fit ad hoc to an exponential using linear regression. In the experiments where the channel filled with ultrasound contrast agent was sonicated, the location of the activity was compared to the location of the channel seen in a standard MRI sequence.

The resolution of the passive cavitation maps depends on the frequency content of the recorded emissions, the distance of the cavitation activity from the face of the linear array (z), and the array's aperture (D). For emissions with a frequency f, the −3dB transverse and axial resolutions of the cavitation maps are approximately and , respectively, where and λ = c/f.55 The focal spot of the MRgFUS device was steered to different targets within the ultrasound imaging plane, and z varied between 10 and 15 cm. Estimates of the expected resolution in the cavitation maps were made individually for each sonication. For these estimates, we used the position of the focal point of the MRgFUS device and the median frequency content of the recorded emissions, which was found by finding the centroid of the emissions’ power spectra (i.e., effective frequency) using the following expression:

| (6) |

where NPS is the acoustic emissions power spectrum that is normalized to the background power spectrum (i.e., to a previous acquisition obtained in the absence of apparent cavitation activity), and f1 and f2 specify the bandwidth of the acquisition (1.0–5.5 MHz).

The impact of the ultrasound imaging probe on the MRTI measurements was evaluated by measuring the standard deviation in the temperature maps in a region of interest that was not heated and that was otherwise free of artifacts. These measurements were made for ten sonications in the quality assurance phantom with and without the imaging probe present.

RESULTS

The simultaneous acquisition of MRI and ultrasound data allowed us to compare both the localization and magnitudes of the heating and cavitation activity. Cavitation-enhanced heating was manifested by (i) colocalized focal heating and cavitation activity, (ii) a substantial increase in heating compared to sonications that did not produce broadband emissions, and (iii) a large temperature variation within the targeted region.

A representative example of a single passive map with and without background correction during a cavitation-enhanced heating experiment is shown in Fig. 2. The cavitation activity appeared elongated in the axial direction of the ultrasound imaging array, which was expected based on its geometry and the large distance (10–15 cm) between it and the focal point of the MRgFUS device. Normalizing each map to a map obtained at a lower power without inertial cavitation reduced the artifacts in front of and behind the cavitation activity in the axial direction.

Figure 2.

(a) Individual passive acoustic maps obtained during cavitation-enhanced heating in a phantom-filled macaque skull before and after background correction. With this correction, maps where broadband emissions were observed were normalized to a map obtained during an earlier sonication at a lower power level at the same target, according to Eq. 4. The highest power sonication where broadband signals were not observed was used for this normalization. (b) Data are shown here relative to the maximum intensity in the corrected and uncorrected maps. The correction reduced signals appearing in front of and behind the focal activity in the axial direction. These data were obtained during the sonications shown in Fig. 7.

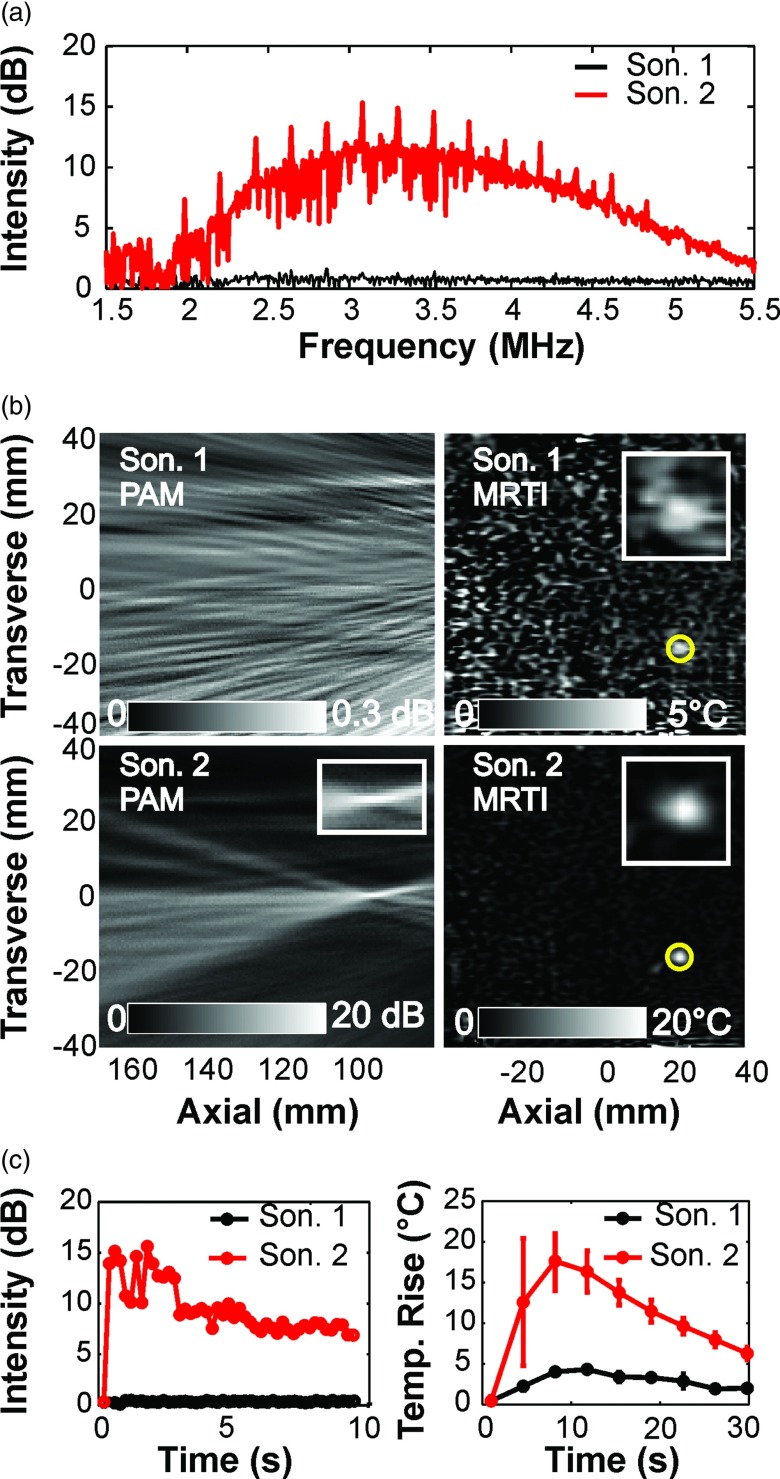

Representative examples of cavitation activity and heating for cases with and without broadband emissions are shown in Fig. 3a. When broadband signals were not present in the PAM [Fig. 3b, Sonication 1, 70 W], no localized activity was observed in the corresponding cavitation maps. In contrast, when broadband emissions were observed, a strong localized signal was observed in the passive maps [Fig. 3b, Sonication 2, 90 W]. The strength of this cavitation activity relative to maps acquired at a lower power level without broadband emissions was 20 dB or more. The localized cavitation activity was observed throughout the sonication, and in most cases its strength was relatively constant over time [Fig. 3c].

Figure 3.

Acoustic emissions, MRTI, and passive cavitation maps obtained simultaneously during two successive sonications at a target in the quality assurance phantom. (a) The power spectra of the cavitation activity obtained during the two sonications. During the second sonication (acoustic power: 90 W), substantial broadband and harmonic emissions were observed. No activity was observed during the first sonication (70 W) (b) Maps showing the intensity of the cavitation activity (left) and the focal heating (right) for these two sonications. At this target, the second sonication resulted in significant cavitation activity and a marked increase in heating; no cavitation activity was evident during the first sonication, and only a small temperature rise was observed. The axial and transverse directions of the ultrasound imaging array with respect to the images are noted. (c) The maximum signal in the cavitation maps (left) and the average temperature rise in the focal region (right) as a function of time. The cavitation activity began at the start of the sonication, and was sustained throughout. Note the rapid and marked temperature increase and the large error bars when cavitation activity was induced.

In the absence of broadband emissions, only a moderate temperature rise (3–5 °C) was observed in MRTI [Fig. 3c]. In the presence of broadband emissions and localized cavitation activity, the temperature rise produced was several times higher [Fig. 3c]—substantially larger than what would be expected from the increase in acoustic power. For example, in the example Fig. 3, the power level was increased by 29% (from 70 to 90 W), but the peak temperature rise increased from 3 to 16.5 °C, more than a fivefold increase. Large spatial temperature variation within the focal region was also observed during heating when cavitation activity was present [Fig. 3c].

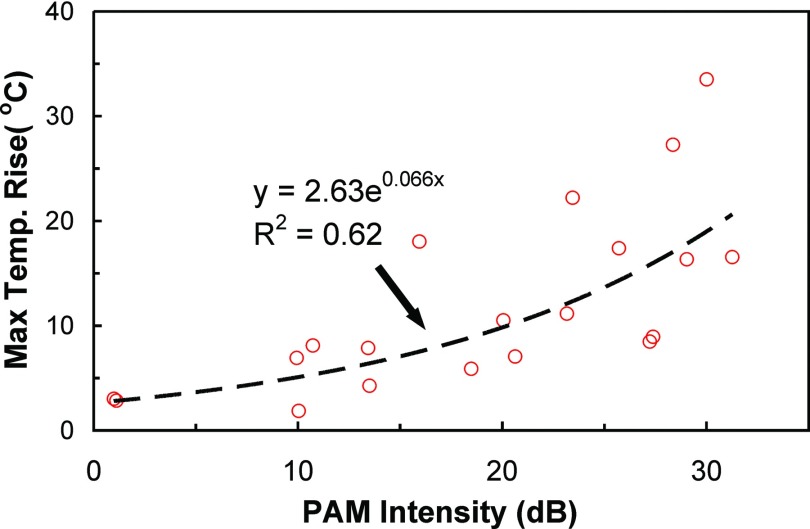

The peak temperature rise achieved per acoustic watt varied from location to location, and the production of broadband emissions and enhanced heating were not clearly related to the power level; power levels that produced strong broadband emissions at some targets did not produce any broadband emissions at others. In particular, when the focal point was steered to large distances (>2 cm) from the geometrical focus of the hemispherical array FUS, higher powers were required to induce the same temperature rise and to generate inertial cavitation. In contrast to the power, a relationship between the temperature rise at the end of the sonication and the intensity in the passive maps was observed. While there was substantial variation between individual measurements, a nonlinear relationship between the strength of the cavitation activity and the resulting temperature rise was evident (Fig. 4). Regression of this data to an exponential yielded a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.62.

Figure 4.

Plot showing the maximum temperature rise measured via MRTI during 20 sonications in the quality assurance phantom as a function of the corresponding maximum intensity measured in the passive cavitation maps. A fit of the data to an exponential (dashed line) is also shown.

Despite issues with MRTI that added uncertainty to our registration (see below), good agreement was found between the location of the maximum cavitation activity in the averaged passive acoustic maps and the center of the focal heating in MRTI. The mean distance between the targets identified by the two modalities was −3.4 ± 2.1 mm and −0.1 ± 3.3 mm in the axial and transverse directions of the ultrasound array, respectively. Figure 5a shows this variation when the individual cavitation maps were considered. The histograms in that figure show the difference in position for all of the individual maps where detectable cavitation activity was present near the expected location; 93% of the maps were included in this analysis. The mismatch between the heating and cavitation activity positions was often larger than might be expected based on the expected resolution of the cavitation maps. This resolution, which depends on the geometry and frequency response of the ultrasound imaging array, the frequency content of the emissions, and the distance of the array from the sonicated targets, varied from location to location [Fig. 5b, 5c]. In most cases, the expected axial resolution of the cavitation maps was between 5 and 10 mm, and the expected transverse resolution was less than 0.8 mm. As can be seen in Fig. 5d, the resolution of the passive maps was better as the focal point of the MRgFUS device was steered closer to the face of the imaging array.

Figure 5.

Registration accuracy of the MRTI and cavitation mapping, and resolution of the passive imaging. (a) Histogram showing the mismatch in the locations of the maximum heating and cavitation activity after registration of the MRI and ultrasound imaging coordinate spaces. Histograms for the transverse and axial directions of the ultrasound imaging array from all the individual cavitation maps. Cavitation activity was not detected in 46 of the 676 cavitation maps; they were excluded from this analysis. Zero indicates exact colocalization; negative values indicate that the location of the maximum cavitation activity was further to the left of the heating in the axial direction or above it in the transverse direction in the images in (d). (b) and (c) Histograms showing the axial and transverse resolutions of the cavitation maps, which varied from location to location depending on the location of the focal region and the frequency content of the recorded acoustic emissions. The effective frequency of the acoustic emissions ranged from 2.8 to 3.4 MHz (mean value: 3.1 MHz). The distance of the sonicated targets from the array varied between 10 and 15 cm. The highest resolution was obtained from cavitation maps from the targets closest to the array that also had highest effective frequency. (d) Fusion of cavitation and temperature maps. Yellow circles are centered at the point of maximum heating, and white circles are centered at the maximum pixel value of the cavitation maps. The red area shows the 90% contour of the cavitation maps. Note how the length of the apparent cavitation activity is reduced when the focal region was steered closer to the imaging array.

In two of the experiments in the quality assurance phantom we performed additional sonications where B-mode images were acquired instead of PAM (Fig. 6). An “x” shaped region was observed centered on the focal region that resembled the signal obtained with PAM. The strength of the signal in this region in B-mode was reduced when the focus was steered away from the ultrasound array center (second target in Fig. 6); this reduction was not observed in the passive imaging. The example shown in Fig. 6 was a case where microbubble activity was observed at a previously sonicated target in addition to the focal region of the MRgFUS device. This activity was observed both in the B-mode images and in the cavitation maps. However, it was not seen in the MRTI.

Figure 6.

Focal heating in MRTI and cavitation activity mapped with passive and active ultrasound imaging. (Top) MRTI acquired during sonication of two targets in the quality assurance phantom. (Middle and bottom) The corresponding passive cavitation maps and B-mode images acquired during sonication at these targets. The yellow circles are centered on the maximum temperature elevation; red crosses indicate the location of maximum signal in the passive cavitation maps. Acoustic emissions arising from the first target were observed when sonicating the second target (arrows). The acoustic power levels in the first and second target were 50 and 100 W, respectively. Note that the four ultrasound images were collected during different sonications at the powers mentioned above; the focal heating in MRTI was similar in each case. The axial and transverse directions of the ultrasound imaging array with respect to the images are noted. The appearance of the void in focal heating was presumably due to heat-induced PRF changes that were greater than the receive bandwidth per voxel in the sequence used for MRTI. Such changes caused the signal in the heated area to shift by one voxel in the frequency encode direction. Phase wrap may have also occurred.

To test the ability of the system to image transcranially, these experiments were repeated using an ex vivo monkey skull filled with brain mimicking material (Fig. 7). Taking into account errors described above in the MRTI, good colocalization of cavitation activity and the focal heating was observed, suggesting that skull-induced aberrations were not significant. In addition to activity at the focal region and at previously sonicated targets, we also observed cavitation activity at the phantom-skull interface [Fig. 7a yellow dashed circle] that resulted in measurable heating (∼5 °C). This activity was presumably due air bubbles that were trapped when the skull was filled with phantom material. Emissions originating from other locations in the skull were not observed.

We also found that it was possible to map cavitation activity through the macaque skull during low-power burst sonications with an ultrasound contrast agent (Fig. 8). At the power level used (5 W), sonication in the phantom material without the microbubble agent in the vessel-mimicking phantom produced little or no cavitation activity. In contrast, when the microbubble agent was introduced, pronounced cavitation activity was observed. Overall, 40 passive cavitation maps were obtained during two sonications. In every case, localized activity was evident. Fusion of the cavitation maps with presonication MRI showed good colocalization of the microbubble activity (white circle) to the targeted area (yellow circle). The peak cavitation activity overlapped in the axial direction with the location of the vessel mimicking channel. There was a slight mismatch in the transverse direction (3 mm). The average spectral content of the emissions are shown in Fig. 8b. Pronounced signals at multiple harmonics and ultraharmonics of the FUS device were observed, along with broadband emissions.

Figure 8.

Transcranial passive cavitation mapping during sonication on a channel filled with diluted ultrasound contrast agent in a phantom-filled ex vivo macaque skull. (a) Region with cavitation activity superimposed on a T1-weighted MR image showing the channel that was filled with ultrasound contrast agent. The region where the average signal in the cavitation maps was within 5% of the maximum activity is shown in red. The location of this activity overlapped with the position of the channel. The corresponding power spectrum for this sonication is shown below (b). Low-level broadband emissions were observed along with substantial harmonic activity.

In general, the presence of the ultrasound imaging probe and the acoustic mirror had little effect on the performance of the MRgFUS system to generate at tight focus. No apparent difference was observed in the shape of the focal heating evident in MRTI with this equipment in place. The presence of the ultrasound device did increase the noise level in the MRTI, but it remained below ±1 °C; the average standard deviation in nonheated regions in MRTI was 0.7 ± 0.09 °C with the ultrasound imaging probe present, and 0.3 ± 0.07 °C without it. An artifact that covered a portion of the phantom was evident in some images when the probe and acoustic mirror were present [see large artifact at the bottom of the images for target 2 in Fig. 7 for an example]. It appeared when the phase encoding direction was in the right/left direction. The appearance of the artifact was consistent with a “cusp” artifact,56 which is normally caused by gradient nonlinearities or magnetic field inhomogeneity and excitation of signal outside of the field of view. Here it was presumably due to strong magnetic field inhomogeneities around the brass reflector or the imaging array.

DISCUSSION

In the present study MRTI and PAM were combined so that the thermal and mechanical effects of focused ultrasound could be localized and assessed simultaneously. We demonstrated that PAM could be integrated into the challenging environment of a transcranial clinical MRgFUS system developed for brain thermal ablation and observed a correlation between acoustic emissions strength, which was relatively constant over time, with the temperature rise achieved at the end of the sonication.

The low frequency MRgFUS device (220 kHz) utilized here was designed to purposely nucleate cavitation to enhance the heating at the focal region in order to expand the volume in the brain that can be targeted for thermal ablation by transcranial FUS without significant aberration corrections and overheating the skull. Such enhancement of the focal heating was observed in these experiments, both in the phantom and in the phantom-filled skull. Currently, this system uses single-channel PCD's to verify the presence of cavitation activity and to evaluate its level. Using imaging instead of simple PCD's can provide additional control to the procedure by enabling one to confirm that the cavitation activity is happening at the desired location.

The correlation we observed between cavitation activity and the temperature rise at the end of the sonication is encouraging for such emissions-based control over cavitation-enhanced ablation. Previous investigations have identified a relationship between cavitation power and rate of temperature increase.57 Others have observed a complicated relationship between acoustic emissions and instantaneous temperature rise58 and have developed models that use the emissions along with other factors to predict the temperature rise during cavitation-enhanced heating. Here, we observed a relatively constant level of cavitation activity during the sonication, which led us to investigate whether the temperature at the end of the sonication was related to the cavitation level. A correlation was observed (R2 = 0.62), although there was substantial variation between sonications. If this variation can be reduced, it may be possible to use PAM at the start of sonication to predict the temperature rise at the end of the sonication, or to use it online to control the acoustic output in order to achieve a desired cavitation, and thus thermal, endpoint. Future work is needed, however, to explore whether this correlation holds in tissue and over a broad range of acoustic parameters. While the acoustic properties (sound speed, attenuation) of our phantom were close to reported values for brain, factors that influence cavitation are likely to be quite different for in vivo tissue than in a homogeneous phantom.

The variability between the PAM and MRTI measurements that we observed could have been due to varying contributions of different modes of heating (i.e., absorption of high-frequency emissions produced during microbubble collapse, viscous heating, etc.18) for different sonications, or perhaps to differences in heating produced by a small number of violently collapsing microbubbles versus a cloud of microbubbles undergoing less violent collapse, which could produce emissions with similar strength. The variation could also have been due to migration of the heated region toward the transducer out of the planes used for MRTI and PAM and to errors in our MRTI sequence that occurred at high temperatures. Correcting such errors in the image acquisitions may reduce this variability.

We also observed some variability in the registration between the focal heating and cavitation activity. We suspect this variability can largely be explained by issues with MRTI. The parameters we used for MRTI were based on those used clinically with this MRgFUS device for thermal ablation,53 where imaging with a high SNR is difficult due to the challenges in integrating an MRI coil into the water-filled hemisphere transducer. A low receiver bandwidth is used to improve the SNR and enable MRTI with a noise level better than ±1 °C in patients. A low bandwidth can also introduce image distortions and shifts in the image when the phase- and frequency-encoding directions are swapped. An example of such shifts is shown in Fig. 7a, where the apparent location of the skull shifted several millimeters when the encoding directions were swapped. In addition, we observed hysteresis of a millimeter or more in the position of the patient table after it was advanced in and out of the MRI scanner. This hysteresis (which was subsequently corrected by the MRgFUS system manufacturer) likely induced error in the transverse direction in the registration. Additional possible sources for this variability were registration errors, errors in our sound speed estimates, and perhaps cavitation activity in the focal region that was outside of the ultrasound imaging plane. Future work with different MRTI scan parameters is needed to investigate the precise registration of the cavitation activity and heating.

Previous evaluation with MRTI have shown that when cavitation-enhanced heating occurs during sonication, the shape of the heated zone along the direction of the FUS beam can be altered, and the heated region can migrate towards the transducer.19 Such changes could not be observed in the present study, since the MRTI was acquired in the focal plane. Here, cavitation-enhanced heating was evident by a higher temperature rise than was expected from the acoustic power and an increased spatial variation within the focal region (Fig. 3). The changes in heating patterns evident in MRTI when cavitation-enhanced heating occurs are qualitative and are obtained at a lower temporal resolution than needed for control of cavitation, which can occur on very short timescales. The presence of cavitation in PAM is definitive and can be obtained at very high frame rates.

PAM was also able to identify cavitation activity away of the sonicated region, sometimes without apparent heating evident in MRTI. In some cases, this activity occurred at previously sonicated targets, presumably due to microbubbles that remained in the phantom for extended periods. While it is not known whether this effect will occur in vivo, being able to monitor and detect cavitation activity at unexpected locations will be important for safety. Such monitoring is expected to be particularly important with hemispherical FUS devices designed for transcranial sonication, where the beam path covers the entire head and will often include previously sonicated targets.

B-mode ultrasound imaging also appeared to be capable of localizing the focal region during sonication with broadband emissions as well as activity from previously sonicated locations. However, we did not simply observe a hyperechoic spot as one might expect with B-mode imaging of a bubble cloud. Instead, the images resemble those presented by Salgaonkar et al., during passive cavitation detection.40 They also resemble images shown by Wu et al., who showed that under certain conditions, the interference patterns in B-mode imaging can be used to localize the focal region during continuous-wave sonication with a high-intensity FUS beam.59 This interference may have masked any hyperechoic region. In contrast to B-mode, with passive mapping, the presence of the FUS beam does not interfere with the image formation, and one can easily filter out the FUS frequency and its harmonics if desired. Others have shown that microbubbles nucleated during sonication can be detected immediately after sonication.41 PAM has the advantage of only requiring one transmission through the skull, and scatterers cannot be confused with sound emitters.

We cannot rule out the possibility that some of the signal we observed in PAM was due to nonlinear sound propagation of the FUS beam instead of signals produced by microbubble activity. However, due to the large differences in frequency between the imaging and FUS devices, our normalization of the passive maps to acquisitions acquired at a slightly lower power level, and the fact that most of the energy in the spectra appeared to be broadband, and not harmonic emissions, we expect that in these experiments that contributions from nonlinear propagation of the FUS beam were minor. These contributions might be more significant if an imaging array with a lower central frequency is used for PAM. In such cases, frequency-selective reconstructions45 that exclude harmonics of the FUS device may be helpful. On the other hand, if significant harmonics due to nonlinear sound propagation can be recorded during sonication below the inertial cavitation threshold, it could be useful. If one can image the focal region with PAM before inertial cavitation occurs, it may aid in rapidly localizing the position of the FUS beam and could improve registration between PAM and MRI.

In addition to improving our ability to monitor and control cavitation-mediated FUS therapies, these abilities of passive and active ultrasound imaging, when combined with the anatomical and temperature mapping abilities of MRI can provide a useful research tool. For example, the ability to simultaneously map temperature and cavitation activity, along with the correlation observed here, will be of interest in developing and validating models of cavitation-enhanced heating.18, 60 We also expect that this multimodal approach can be used for the development and validation of passive cavitation mapping and other ultrasound-based approaches (such as ultrasound temperature imaging61) to plan, guide, or evaluate FUS therapies—even for cases where the procedure will ultimately be guided by ultrasound imaging instead of MRI. Outside the brain, information from ultrasound imaging can also be used to track the position of moving organs within the MRI.62

We are currently testing this integrated monitoring system for cavitation-enhanced thermal ablation, “nonthermal” ablation using an injected microbubble agent, and drug delivery. Initial in vivo tests performed with this system are promising.63 Improvements in the quality and accuracy of the constructed maps, evaluation of out-of-plane cavitation activity, compensating for skull-induced beam aberrations, modeling the entire procedure for quantifying the acoustic emissions and estimate the forces exerted by the microbubbles, and tests with ex vivo human skull samples are part of our ongoing efforts.

CONCLUSIONS

We successfully integrated an ultrasound imaging system into a clinical MRgFUS system designed for transcranial sonication into the brain and obtained simultaneous PAM and MRTI in tissue-mimicking phantoms. The location of the focal heating evident in MRTI and the cavitation activity seen in PAM agreed on average, but some variation was observed which was presumed to arise largely from distortions and other errors in the MRTI. The strength of the cavitation activity, which was relatively constant over time, was correlated with the peak temperature rise, although there was substantial variation. The presence of the ultrasound imaging array did not have significant impact on the performance of the MRgFUS system. This integrated system is promising to achieve comprehensive guidance of FUS therapies that utilize microbubble effects and/or heating and also provide a tool to study acoustic cavitation and its bioeffects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Greg Clement for providing the Verasonics system, to F. Can Meral for his help with the ultrasound imaging engine, and to Tony Wei and Charles Maneval for their help with building the penetration panel. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. R25CA089017, P41EB015898, P41RR019703, and RC2NS069413. The focused ultrasound system was supplied by InSightec.

References

- ter Haar G., “Therapeutic applications of ultrasound,” Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 93, 111–129 (2007). 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E., Jeanmonod D., Morel A., Zadicario E., and Werner B., “High-intensity focused ultrasound for noninvasive functional neurosurgery,” Ann. Neurol. 66, 858–861 (2009). 10.1002/ana.21801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E. L. et al. , “Randomized trial of hyperthermia and radiation for superficial tumors,” J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 3079–3085 (2005). 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moros E. G., Penagaricano J., Novak P., Straube W. L., and Myerson R. J., “Present and future technology for simultaneous superficial thermoradiotherapy of breast cancer,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 26, 699–709 (2010). 10.3109/02656736.2010.493915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dromi S. et al. , “Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound and low temperature-sensitive liposomes for enhanced targeted drug delivery and antitumor effect,” Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2722–2727 (2007). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Smet M., Heijman E., Langereis S., Hijnen N. M., and Grull H., “Magnetic resonance imaging of high intensity focused ultrasound mediated drug delivery from temperature-sensitive liposomes: An in vivo proof-of-concept study,” J. Controlled Release 150, 102–110 (2011). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staruch R., Chopra R., and Hynynen K., “Localised drug release using MRI-controlled focused ultrasound hyperthermia,” Int. J. Hyperthermia 27, 156–171 (2011). 10.3109/02656736.2010.518198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhon E. et al. , “Spatial and temporal control of transgene expression in vivo using a heat-sensitive promoter and MRI-guided focused ultrasound,” J. Gene Med. 5, 333–342 (2003). 10.1002/jgm.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. et al. , “Controlled ultrasound tissue erosion,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 51, 726–736 (2004). 10.1109/TUFFC.2004.1308731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith S. J., Kassell N. F., Goren O., and Harnof S., “Transcranial MR-guided focused ultrasound sonothrombolysis in the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage,” Neurosurg. Focus 34(5), E14–E21 (2013). 10.3171/2013.2.FOCUS1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A. D., Cain C. A., Duryea A. P., Yuan L., Gurm H. S., and Xu Z., “Noninvasive thrombolysis using pulsed ultrasound cavitation therapy - histotripsy,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 35, 1982–1994 (2009). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K., Uchida T., Ogawa K., Yamashita N., and Tamura K., “Induction of cell-membrane porosity by ultrasound,” Lancet 353, 1409 (1999). 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01244-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport N., Gao Z., and Kennedy A., “Multifunctional nanoparticles for combining ultrasonic tumor imaging and targeted chemotherapy,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 1095–1106 (2007). 10.1093/jnci/djm043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan-Peregrino M. et al. , “Cavitation-enhanced delivery of a replicating oncolytic adenovirus to tumors using focused ultrasound,” J. Controlled Release 169(1–2), 40–47 (2013). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnota G. J. et al. , “Tumor radiation response enhancement by acoustical stimulation of the vasculature,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2033–E2041 (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1200053109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S. et al. , “Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 32, 1257–1267 (2006). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K. et al. , “Renal ultrafiltration changes induced by focused US,” Radiology 253, 697–705 (2009). 10.1148/radiol.2532082100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt R. G. and Roy R. A., “Measurements of bubble-enhanced heating from focused, MHz-frequency ultrasound in a tissue-mimicking material,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 27, 1399–1412 (2001). 10.1016/S0301-5629(01)00438-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokka S. D., King R., and Hynynen K., “MRI-guided gas bubble enhanced ultrasound heating in in vivo rabbit thigh,” Phys. Med. Biol. 48, 223–241 (2003). 10.1088/0031-9155/48/2/306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung Y. S., Liu H. L., Wu C. C., Ju K. C., Chen W. S., and Lin W. L., “Contrast-agent-enhanced ultrasound thermal ablation,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 32, 1103–1110 (2006). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C. R., Ritchie R. W., Gyongy M., Collin J. R., Leslie T., and Coussios C. C., “Spatiotemporal monitoring of high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy with passive acoustic mapping,” Radiology 262, 252–261 (2012). 10.1148/radiol.11110670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farny C. H., Holt R. G., and Roy R. A., “Temporal and spatial detection of HIFU-induced inertial and hot-vapor cavitation with a diagnostic ultrasound system,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 35, 603–615 (2009). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T., Wang G., Hu K., Ma P., Bai J., and Wang Z., “A microbubble agent improves the therapeutic efficiency of high intensity focused ultrasound: A rabbit kidney study,” Urol. Res. 32(1), 14–19 (2004). 10.1007/s00240-003-0362-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman J. C., “Proton resonance shift of water in the gas and liquid states,” J. Chem. Phys. 44, 4582–4592 (1966). 10.1063/1.1726676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R. D., Hinks R. S., and Henkelman R. M., “Ex vivo tissue-type independence in proton-resonance frequency shift MR thermometry,” Magn. Reson. Med. 40, 454–459 (1998). 10.1002/mrm.1910400316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K., Chung A. H., Hynynen K., and Jolesz F. A., “Calibration of water proton chemical shift with temperature for noninvasive temperature imaging during focused ultrasound surgery,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 8, 175–181 (1998). 10.1002/jmri.1880080130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y. et al. , “A precise and fast temperature mapping using water proton chemical shift,” Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 814–823 (1995). 10.1002/mrm.1910340606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke V., Vigen K. K., Sommer G., Daniel B. L., Pauly J. M., and Butts K., “Referenceless PRF shift thermometry,” Magn. Reson. Med. 51, 1223–1231 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enholm J. K., Kohler M. O., Quesson B., Mougenot C., Moonen C. T. W., and Sokka S. D., “Improved volumetric MR-HIFU ablation by robust binary feedback control,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57(1), 103–113 (2010). 10.1109/TBME.2009.2034636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K., “MRIgHIFU: A tool for image-guided therapeutics,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 34, 482–493 (2011). 10.1002/jmri.22649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley A. A., Frizzell L. A., Apfel R. E., Holland C. K., Madanshetty S., and Roy R. A., “Thresholds for cavitation produced in water by pulsed ultrasound,” Ultrasonics 26, 280–285 (1988). 10.1016/0041-624X(88)90018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele P. P., Effects of Ultrasound on “Solid” Mammalian Tissues and Tumors in Vivo (Plenum, New York, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Leighton T. G., The Acoustic Bubble (Academic, San Diego, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Bazan-Peregrino M., Arvanitis C. D., Rifai B., Seymour L. W., and Coussios C. C., “Ultrasound-induced cavitation enhances the delivery and therapeutic efficacy of an oncolytic virus in an in vitro model,” J. Controlled Release 157, 235–242 (2012). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis C. D., Bazan-Peregrino M., Rifai B., Seymour L. W., and Coussios C. C., “Cavitation-enhanced extravasation for drug delivery,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 37, 1838–1852 (2011). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis C. D., Livingstone M. S., Vykhodtseva N., and McDannold N., “Controlled ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier disruption using passive acoustic emissions monitoring,” PLoS ONE 7(9), e45783–e45798 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0045783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N., Vykhodtseva N., and Hynynen K., “Targeted disruption of the blood-brain barrier with focused ultrasound: Association with cavitation activity,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 793–807 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/4/003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung Y. S., Vlachos F., Choi J. J., Deffieux T., Selert K., and Konofagou E. E., “In vivo transcranial cavitation threshold detection during ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in mice,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 6141–6155 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/20/007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyongy M. and Coussios C. C., “Passive spatial mapping of inertial cavitation during HIFU exposure,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 48–56 (2010). 10.1109/TBME.2009.2026907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgaonkar V. A., Datta S., Holland C. K., and Mast T. D., “Passive cavitation imaging with ultrasound arrays,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 3071–3083 (2009). 10.1121/1.3238260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateau J., Aubry J.-F., Pernot M., Fink M., and Tanter M., “Combined passive detection and ultrafast active imaging of cavitation events induced by short pulses of high-intensity ultrasound,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 58(3), 517–532 (2011). 10.1109/TUFFC.2011.1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateau J., Aubry J.-F., Chauvet D., Boch A.-L., Fink M., and Tanter M., “In vivo bubble nucleation probability in sheep brain tissue,” Phys. Med. Biol. 56(22), 7001–7015 (2011). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/22/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. et al. , “Extracorporeal high intensity focused ultrasound ablation in the treatment of patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma,” Ann. Surg. Oncol. 11(12), 1061–1069 (2004). 10.1245/ASO.2004.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. et al. , “Clinical utility of a microbubble-enhancing contrast (‘SonoVue’) in treatment of uterine fibroids with high intensity focused ultrasound: A retrospective study,” Eur. J. Radiol. 81(12), 3832–3838 (2012). 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth K. J. et al. , “Passive imaging with pulsed ultrasound insonations,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132, 544–553 (2012). 10.1121/1.4728230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. M., O’Reilly M. A., and Hynynen K., “Transcranial passive acoustic mapping with hemispherical sparse arrays using CT-based skull-specific aberration corrections: A simulation study,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58(14), 4981–5005 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/14/4981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K. et al. , “500-element ultrasound phased array system for noninvasive focal surgery of the brain: A preliminary rabbit study with ex vivo human skulls,” Magn. Reson. Med. 52(1), 100–107 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton S. J., Carr B. J., and Witten A. J., “Passive imaging of underground acoustic sources,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 2840–2847 (2006). 10.1121/1.2188667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton S. J. and Won I. J., “Time exposure acoustics,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 38, 1337–1343 (2000). 10.1109/36.843027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N., Arvanitis C. D., Vykhodtseva N., and Livingstone M. S., “Temporary disruption of the blood–brain barrier by use of ultrasound and microbubbles: Safety and efficacy evaluation in rhesus macaques,” Cancer Res. 72(14), 3652–3663 (2012). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N., Park E. J., Mei C. S., Zadicario E., and Jolesz F., “Evaluation of three-dimensional temperature distributions produced by a low-frequency transcranial focused ultrasound system within ex vivo human skulls,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 57, 1967–1976 (2010). 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck F. A., “Acoustic properties of tissue at ultrasonic frequencies,” in Physical Properties of Tissue. A Comprehensive Reference Book (Academic, London, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmonod D. et al. , “Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound: Noninvasive central lateral thalamotomy for chronic neuropathic pain,” Neurosurg. Focus 32(1), E1–E11 (2012). 10.3171/2011.10.FOCUS11248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis C. D. and McDannold N., “Simultaneous temperature and cavitation activity mapping,” Proc. IEEE Int. Ultrason. Sumpos. 128–131 (2011). 10.1109/ULTSYM.2011.0032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gyongy M. and Coussios C. C., “Passive cavitation mapping for localization and tracking of bubble dynamics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128, EL175–EL180 (2010). 10.1121/1.3467491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala N. and Zhou X. J., “Reduction of fast spin echo cusp artifact using a slice-tilting gradient,” Magn. Reson. Med. 64, 220–228 (2010). 10.1002/mrm.22418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farny C. H., Glynn Holt R., and Roy R. A., “The correlation between bubble-enhanced HIFU heating and cavitation power,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 175–184 (2010). 10.1109/TBME.2009.2028133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast T. D., Salgaonkar V. A., Karunakaran C., Besse J. A., Datta S., and Holland C. K., “Acoustic emissions during 3.1 MHz ultrasound bulk ablation in vitro,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 34, 1434–1448 (2008). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-C., Chen C.-N., Ho M.-C., Chen W.-S., and Lee P.-H., “Using the acoustic interference pattern to locate the focus of a high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) transducer,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 34(1), 137–146 (2008). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenfeldt S., Lohse D., and Zomack M., “Sound scattering and localized heat deposition of pulse-driven microbubbles,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 107, 3530–3539 (2000). 10.1121/1.429438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. and Ebbini E. S., “Real-time 2-D temperature imaging using ultrasound,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 12–16 (2009). 10.1109/TBME.2009.2035103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther M. and Feinberg D. A., “Ultrasound-guided MRI: Preliminary results using a motion phantom,” Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 27–32 (2004). 10.1002/mrm.20140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis C. D., Livingstone M. S., and McDannold N., “Combined ultrasound and MR imaging to guide focused ultrasound therapies in the brain,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58(14), 4749–4761 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/14/4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorny K. R., Hangiandreou N. J., Hesley G. K., Gostout B. S., McGee K. P., and Felmlee J. P., “MR guided focused ultrasound: Technical acceptance measures for a clinical system,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51(12), 3155–3173 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/12/011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Grosso V. A. and Mader C. W., “Speed of sound in pure water,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 52, 1442–1446 (1972). 10.1121/1.1913258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marquet F. et al. , “Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound therapy based on a 3D CT scan: Protocol validation and in vitro results,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54(9), 2597–2613 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]