Abstract

Objective

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) analysis by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy remains a diagnostic hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The clinical relevance of ANA fine-specificities in SLE has been addressed repeatedly, whereas studies on IF-ANA staining patterns in relation to disease manifestations are very scarce. This study was performed to elucidate whether different staining patterns associate with distinct SLE phenotypes.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

One university hospital rheumatology unit in Sweden.

Participants

The study population consisted of 222 cases (89% women; 93% Caucasians), where of 178 met ≥4/11 of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-82) criteria. The remaining 20% had an SLE diagnosis based on positive IF-ANA (HEp-2 cells) and ≥2 typical organ manifestations at the time of diagnosis (Fries’ criteria).

Outcome measures

The IF-ANA staining patterns homogenous (H-ANA), speckled (S-ANA), combined homogenous and speckled (HS-ANA), centromeric (C-ANA), nucleolar (N-ANA)±other patterns and other nuclear patterns (oANA) were related to disease manifestations and laboratory measures. Antigen-specificities were also considered regarding double-stranded DNA (Crithidia luciliae) and the following extractable nuclear antigens: Ro/SSA, La/SSB, Smith antigen (Sm), small nuclear RNP (snRNP), Scl-70 and Jo-1 (immunodiffusion and/or line-blot technique).

Results

54% of the patients with SLE displayed H-ANA, 22% S-ANA, 11% HS-ANA, 9% N-ANA, 1% C-ANA, 2% oANA and 1% were never IF-ANA positive. Staining patterns among patients meeting Fries’ criteria alone did not differ from those fulfilling ACR-82. H-ANA was significantly associated with the 10th criterion according to ACR-82 (‘immunological disorder’). S-ANA was inversely associated with arthritis, ‘immunological disorder’ and signs of organ damage.

Conclusions

H-ANA is the dominant IF-ANA pattern among Swedish patients with SLE, and was found to associate with ‘immunological disorder’ according to ACR-82. The second most common pattern, S-ANA, associated negatively with arthritis and organ damage.

Keywords: Antinuclear antibodies, Immunofluorescence microscopy, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Organ damage, Ro/SSA

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The large study population with thoroughly organised data and very few internal missing values constitutes the strength of this study.

Well-defined cut-off levels in autoantibody testing, performed at one single accredited laboratory, were used.

Although this study confirmed several known associations between serological findings and clinical features, it did not have the power to allow comparisons with specific types of cutaneous lupus, renal disease, central or peripheral nervous system manifestations, as well as with clinical features not included in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria.

Introduction

The clinical spectrum of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is exceedingly variable with an unpredictable disease course characteristically with episodes of flares and remissions. Ongoing disease exacerbations and cumulative damage/dysfunction over time can significantly interfere with quality of life.1 Organ systems most commonly involved in SLE include joints, skin, mucous membranes, bone marrow and kidneys. Despite the considerable differences between patients with SLE, the occurrence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in serum at the time of diagnosis is a common finding with very few exceptions.2

An ‘abnormal titre’ of ANA assessed by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy (IF-ANA) is 1 of the 11 criteria for SLE according to the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-82) validated classification criteria3 as well as the 1997 revised criteria.4 Also the recently proposed Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria state that an ANA test ‘above the laboratory reference value’ remains a criterion for SLE, but without specifying the method for ANA assessment.5 Unfortunately, none of the classification grounds state how to define the cut-off level for ANA. Similar to the definition of a positive rheumatoid factor test according to the 1987 ACR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis (RA),6 we advocate a cut-off level of >95th centile among healthy female blood donors to define an abnormal level of ANA analysed by indirect IF microscopy utilising fixed HEp-2 cells as source of nuclear antigens and, importantly, γ-chain specific secondary antibodies to pinpoint IgG-class IF-ANA.7 At this cut-off level, ANA has very high diagnostic sensitivity for SLE, but low diagnostic specificity, with close to 5% prevalence among healthy female blood donors.8 Accordingly, ANA testing should only be carried out on fair clinical indications of ANA-related disease. Although circulating levels of ANA may vary over time in patients with SLE, the correlation between IF-ANA titre and clinical activity is poor.9

Nuclear constituents such as histone proteins, double-stranded (ds) DNA, DNA/histone complexes (nucleosomes), various nuclear enzymes and other proteins/ribonucleoproteins are common target antigens for ANA. On the basis of their different intranuclear distributions, IF-ANA staining patterns can be subdivided into homogenous/chromosomal (H-ANA), centromeric (C-ANA), speckled/extrachromosomal (S-ANA), nucleolar (N-ANA), nuclear membrane, nuclear dot and other defined patterns.10 The most common ANA pattern detected among healthy individuals has been reported as a uniformly distributed staining of HEp-2 cells in the interphase and a chromosomal staining in dividing cells, designated ‘dense fine speckled pattern’, whereas we have actually referred to this staining as a homogenous/chromosomal pattern, that is, H-ANA.11 12 A ‘classical’ homogenous/chromosomal pattern is the most common among patients with SLE from southern Sweden as well as in RA.8 Antibodies against dsDNA, histones and DNA/histone complex all yield a ‘classical’ H-ANA pattern on HEp-2 cells.13 Antibodies against dsDNA, histones and DNA/histone complex all yield an H-ANA pattern.13 The presence of anti-dsDNA, which is included in ACR-82 criterion number 10 designated ‘immunological disorder’, has been regarded as a fairly specific diagnostic marker of SLE and is very common in lupus nephritis.2 10 13–16 S-ANA is generated by antibodies targeting ‘extractable nuclear antigens’ (ENA), that is, a group of extrachromosomal antigens that are readily extracted with 0.15 M sodium chloride, for instance ‘small nuclear ribonucleoprotein’ (snRNP) and the ‘Smith antigen’ (Sm), which are both located on U1-RNP particles.2 10 13 Anti-Sm antibody detected by double radial immunodiffusion (DRID) in gel is highly specific for SLE and practically always occurs together with anti-snRNP. Anti-Sm has been reported to associate with constitutional symptoms (fever, weight-loss and fatigue), nephritis and central nervous system disease, but the sensitivity in cohorts worldwide varies dramatically due to ethnicity.13 17–21 Anti-Sm has also been reported to associate with serositis and Raynaud's phenomenon.19 22–24 N-ANA patterns are not typical of SLE, but rather of systemic sclerosis of the diffuse type.25 N-ANA may be directed against for example, fibrillarin, RNA-polymerase 1–3, ‘PM-Scl’, and Scl-70 (topoisomerase-1).10 13 26 Scl-70, which belongs to the ‘ENA family’, is also found both extrachromosomally in the nucleoplasm and bound to the DNA, thus giving rise to a mixed IF staining pattern. Like Scl-70, the La/SSB antigen may partly localise in nucleoli. Most experience regarding clinical associations to anti-ENA refers to DRID analyses. As regards anti-La/SSB as well as anti-Ro/SSA, a positive DRID test is clinically linked to Sjögren's syndrome and to some extent SLE.22 27–31 A positive anti-La/SSB DRID test generally occurs together with anti-Ro/SSA, whereas anti-Ro/SSA is frequently demonstrated in the absence of anti-La/SSB. Since the concentration of Ro/SSA is low in HEp-2 cells, anti-Ro/SSA escapes detection when non-transfected HEp-2 cells are used as ANA substrate for IF microscopy.32 In a small proportion of pregnant women with circulating anti-Ro52/SSA, transplacental antibody passage to the fetus can result in neonatal lupus, that is, typical congenital skin rash (which vanishes in parallel with elimination of the maternal antibodies) and sometimes also in congenital lifelong complete atrioventricular heart block.33 34

Although several studies have dealt with the clinical significance of ANA fine-specificities in SLE, very few have evaluated if/how different IF-ANA staining patterns may relate to distinct clinical lupus features. In the present study we aimed at comparing IF-ANA staining patterns with defined clinical and laboratory disease manifestations among well-characterised cases of SLE.

Patients and methods

Subjects

Two hundred and twenty-two patients with SLE (198 women and 24 men; mean age 51 years; range 18–88) taking part in the prospective follow-up programme KLURING (a Swedish acronym for ‘Clinical LUpus Register In Northeastern Gothia’) at the Rheumatology Clinic, Linköping University Hospital, Sweden were included between September 2008 and November 2012. This corresponds to about 95% of the expected SLE cases in the catchment area of Linköping and ≥98% of all known SLE cases. The patient material was recently described in detail.35 A total of 178 patients (80%) met the ACR-82 criteria,3 and 44 (20%) had a clinical diagnosis of SLE based on a history of abnormal ANA titre (specified below), and at least two typical organ manifestations at the time of diagnosis (referred to as the Fries’ criteria).36 37 The presence of anticardiolipin antibodies of IgG and/or IgM class detected by ELISA and/or positive lupus anticoagulant test (not classified as an immunological criterion according to ACR-82) was found in 31 of the 44 individuals (70%) in the Fries’ group.

Patients were consecutively recruited; most were prevalent cases (85%), but some (15%) had newly diagnosed SLE at the time of enrolment. Distribution of age at disease onset is demonstrated in figure 1. The median disease duration by year 2012 was 12 years (mean 13.4; range 0–49). Disease severity/organ damage was estimated using the SLICC/ACR damage index (SDI) at the end of year 2011 or from the last observation made.38 Two hundred and six (93%) of the patients were Caucasians. Ninety-two (41%) of the patients were prescribed antimalarials (AM) alone, 68 (31%) other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs±AM and 128 (58%) oral glucocorticoids. IF-ANA staining patterns, anti-ENA reactivity and dsDNA antibodies were analysed on a routine basis at the Clinical immunology laboratory, Linköping university hospital and were extracted from medical records. In many patients, IF-ANA analysis was performed at several occasions over time but discrepant staining patterns were achieved in less than 5% of these cases. Herein, IF-ANA staining pattern from the time-point most adjacent to SLE onset was used for comparisons with clinical and laboratory features.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients with SLE by sex and decade of age at disease onset.

Indirect IF microscopy

ANA was analysed by indirect IF microscopy using multispot slides with fixed HEp-2 cells (ImmunoConcepts, Sacramento, California, USA) as antigen substrate and fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated γ-chain-specific antihuman IgG as detection antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). The cut-off level for a positive ANA test was set at a titre of 1:200, corresponding to >95th centile among 150 healthy female blood donors. Positive ANA tests were categorised regarding IF staining patterns (H-ANA, S-ANA, HS-ANA, N-ANA±other pattern or other staining patterns (oANA). To qualify as an H-ANA pattern, chromatin staining was required in metaphase/anaphase cells and, likewise, absence of chromatin staining was required to qualify as a pure S-ANA pattern. Microscope slides with fixed Crithidia luciliae (ImmunoConcepts) and FITC conjugated γ-chain-specific antihuman IgG (DAKO) were used to analyse IgG-class anti-dsDNA antibodies by IF with a cut-off titre at 1:10, corresponding to >99th centile among 100 (50 males/50 females) healthy blood donors.

Anti-ENA antibodies

Autoantibodies to ENA included the following specificities: Ro/SSA, La/SSB, Sm, snRNP, Scl-70 and Jo-1 and were analysed by DRID (ImmunoConcepts) and/or line-blot technique (ProfilePlus, R052 Euroassay, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). In the case line-blot screening resulted in positive reactions regarding antibodies against Sm, Jo-1 or Scl-70, these specificities were confirmed by DRID in order to qualify as positive. For the other anti-ENA specificities, good reproducibility has been reassured at the performing laboratory.

Routine laboratory analyses

To assess haematological and renal disorders, laboratory tests at selected visits included haemoglobin and blood cell counts (erythrocytes, total leucocyte count, lymphocytes, neutrophils and platelets) as well as urinalysis (dip-slide procedure for erythrocytes, protein and glucose), urinary sediment assessment and serum creatinine. Lupus anticoagulant was performed by the dilute Russell's viper venom test (DRVVT).

Renal histopathology

Thirty-eight of the included patients (ie, 79% of those who fulfilled ACR-82 criterion number 7 ‘renal disorder’) had undergone renal biopsy performed by percutaneous ultrasonography-guided puncture in accordance with a standard protocol. The renal tissue obtained was classified according to the WHO classification for lupus nephritis.39 All biopsies were evaluated by conventional light microscopy, direct IF and electron microscopy.

Statistics

Frequencies of the different IF-ANA staining patterns in the study group were analysed to identify subgroups for further analyses. Clinical and laboratory features were described by their frequencies, for each of the most common pattern subgroups separately. Differences in distributions of different staining patterns regarding clinical and laboratory features were analysed using χ2 tests of independence (alternatively Fisher's exact test in case of small expected frequencies) with Cramer's V as measure of effect size. All statistics were performed using IBM SPSS V.20.0. For each statistical test, exact p values (non-adjusted) are reported.

Ethical considerations

Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Frequencies of clinical and laboratory features are displayed in table 1. Two hundred and nineteen of 222 (99%) were found to be ever ANA positive. Skin disease and arthritis were the most commonly fulfilled ACR-82 criteria followed by ‘haematological disorder’. Twenty-two per cent of the patients had renal disease and 44% showed positive anti-dsDNA antibody test at least once during their disease course. However, five individuals were classified with unknown or oANA since the clinical immunology laboratory was unable to recover documentation of IF-ANA patterns or classified the positive nuclear staining pattern as very rare (nuclear dots). Four of these five individuals were prescribed at least one disease-modifying drug. H-ANA staining was by far the most frequent pattern (54%) followed by S-ANA (22%), HS-ANA (11%), N-ANA±other pattern (9%) and C-ANA (1%). The first four pattern groups were considered large enough for statistical comparisons.

Table 1.

Antinuclear antibody immunofluorescence microscopy staining patterns in relation to clinical and laboratory features among 219 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

| H-ANA (%) | S-ANA (%) | HS-ANA (%) | N-ANA* (%) | C-ANA (%) | oANA (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=119) | (n=49) | (n=24) | (n=19) | p Value | Cramer's V | (n=3) | (n=5) | Total (%) | |

| Clinical feature (ACR–82) | |||||||||

| Malar rash | 42.0 | 53.1 | 41.7 | 31.6 | 0.38 | 0 | 80 | 43.8 | |

| Discoid lupus | 12.6 | 18.4 | 20.8 | 10.5 | 0.57† | 33 | 20 | 15.1 | |

| Photosensitivity | 47.9 | 65.3 | 58.3 | 36.8 | 0.09 | 33 | 80 | 52.5 | |

| Oral ulcers | 10.1 | 16.3 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 0.68† | 0 | 0 | 11.4 | |

| Arthritis | 76.5 | 63.3– | 91.7 | 89.5 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 100 | 100 | 77.2 |

| Serositis | 42.9 | 38.8 | 25.0 | 47.4 | 0.38 | 100 | 20 | 40.6 | |

| Pleuritis | 38.7 | 34.7 | 25.0 | 36.8 | 0.64 | 100 | 20 | 36.5 | |

| Pericarditis | 16.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 15.8 | 0.15† | 33 | 0 | 13.7 | |

| Renal disorder | 24.4 | 16.3 | 29.2 | 15.8 | 0.49 | 33 | 0 | 21.9 | |

| Neurological disorder | 1.7– | 8.2 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 0.04† | 0.17 | 33 | 0 | 5.0 |

| Seizures | 0.8– | 6.1 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 0.02† | 0.19 | 33 | 0 | 4.1 |

| Psychosis | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.22† | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | |

| Haematological disorder | 48.7 | 59.2 | 58.3 | 42.1 | 0.45 | 33 | 0 | 50.2 | |

| Immunological disorder | 64.7+ | 24.5– | 33.3 | 31.6 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 33 | 0 | 47.5 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| ≥6 fulfilled ACR criteria | 26.9 | 24.5 | 20.8 | 15.8 | 0.73 | 33 | 0 | 24.2 | |

| SDI score ≥1 | 59.7 | 30.6– | 54.2 | 57.9 | 0.007 | 0.24 | 67 | 60 | 52.5 |

| Laboratory feature | |||||||||

| Haemolytic anemia | 2.5 | 8.2 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 0.30† | 0 | 0 | 4.1 | |

| Leukocytopenia | 29.4 | 30.6 | 33.3 | 21.1 | 0.84 | 33 | 0 | 28.8 | |

| Lymphocytopenia | 27.7 | 32.7 | 33.3 | 31.6 | 0.90 | 0 | 0 | 28.8 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 10.1 | 16.3 | 12.5 | 5.3 | 0.59† | 0 | 0 | 11.0 | |

| Lupus anticoagulant‡ | 34.6 | 24.3 | 33.3 | 38.5 | 0.68 | 33 | 50 | 32.5 | |

| Anti-dsDNA | 63.9+ | 12.2– | 33.3 | 26.3 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 33 | 0 | 43.8 |

| Anti-Sm | 3.4 | 16.7+ | 4.2 | 10.5 | 0.022† | 0.21 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 |

| Anti-Ro/SSA | 32.8 | 43.8 | 62.5+ | 36.8 | 0.047 | 0.20 | 33 | 0 | 38.5 |

| Anti-La/SSB | 7.0 | 12.8 | 33.3+ | 0.0 | 0.002† | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | 11.8 |

| Anti-snRNP | 6.9– | 47.8+ | 13.6 | 22.2 | <0.001† | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | 20.2 |

*Staining pattern±combination with other pattern(s).

†Fisher's exact test.

‡Not analysed in all patients; H-ANA: n=81, S-ANA: n=37, HS-ANA: n=18, N-ANA: n=13, C-ANA: n=3, oANA: n=2.

+ = positive association, − = negative association.

ACR-82, the 1982 American College of Rheumatology criteria; C-ANA, centromeric; H-ANA, homogenous; HS-ANA, homogenous/peckled; N-ANA, nucleolar; oANA, other pattern; S-ANA, speckled.

Some clinical and laboratory features showed differences in proportions over different staining patterns (table 1). ‘Immunological disorder’ (the 10th ACR-82 criterion) and anti-dsDNA antibodies were more often associated with H-ANA, and less often associated with S-ANA; whereas anti-snRNP showed the opposite direction (moderate to strong effects). Central nervous system disease was less often associated with H-ANA compared to other staining patterns, but the number of affected individuals was very low. Anti-Sm was more often, whereas arthritis and organ damage (SDI ≥1), respectively were less often, associated with S-ANA. Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies were more often associated with HS-ANA. No significant differences in proportions of the number of concomitant ANA fine-specificities over different staining patterns were recorded.

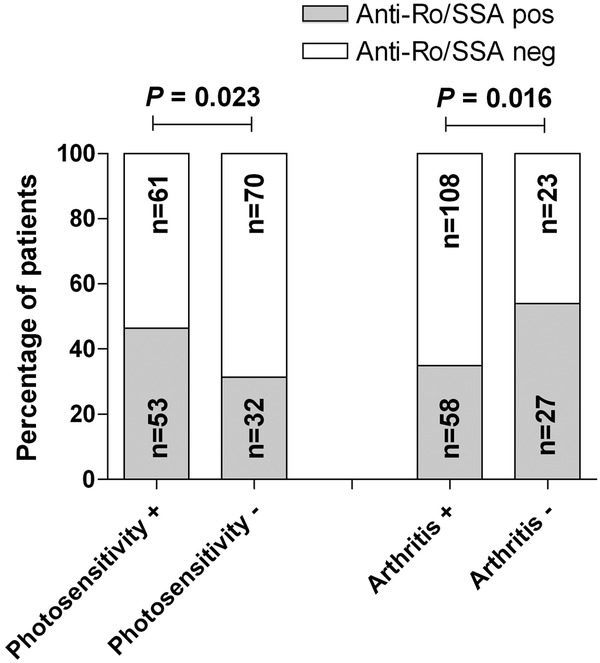

Photosensitivity was significantly associated with anti-Ro/SSA antibodies (figure 2). On the contrary, arthritis was less common among patients with anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. A positive anti-Sm antibody test was significantly associated with lymphocytopenia (Fisher's exact test, p=0.014, Cramer's V=0.19); and as expected, a positive anti-dsDNA antibody test was significantly associated with renal disorder (χ2 test, p<0.001, Cramer's V=0.34).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients fulfilling the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-82) criterion 3 (photosensitivity) and 5 (arthritis) in relation to anti-Ro/SSA antibody status. Photosensitivity was significantly more common, and arthritis less common, in anti-Ro/SSA antibody positive patients with SLE. Data on anti-Ro/SSA antibody status was available in 216 of 222 (97.3%) cases.

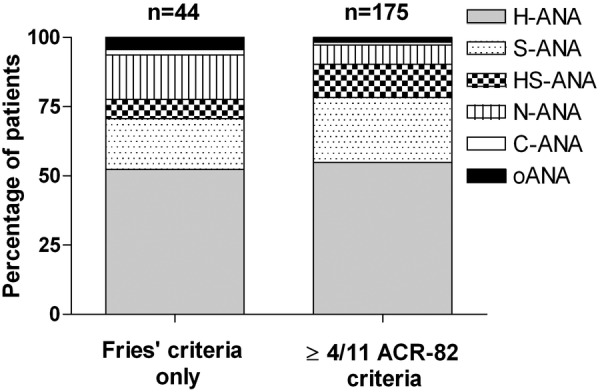

The proportions of different staining patterns in the group of patients fulfilling only the Fries’ criteria and those meeting the ACR-82 criteria are demonstrated in figure 3. The higher proportion of patients with nucleolar staining in the Fries’ group as compared with the ACR-82 group did not meet statistical significance (Fisher's exact test, p=0.064). Figure 4 demonstrates the number of fulfilled ACR criteria in relation to nuclear staining patterns. H-ANA was found to dominate regardless of the number of fulfilled ACR criteria. As indicated in figure 5, H-ANA was significantly more common in patients that had been classified with proliferative lupus nephritis (WHO class 3 or 4) on renal biopsy (χ2 test, p<0.001) compared to other staining patterns.

Figure 3.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) assessed by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy (IF-ANA) staining patterns demonstrated for the 219 ever ANA positive patients with SLE divided on those who only met the Fries’ criteria and those who fulfilled at least 4 of the 11 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-82) criteria.

Figure 4.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) assessed by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy (IF-ANA) staining patterns demonstrated for the 219 ever ANA positive patients with SLE divided on the number of fulfilled the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-82) criteria.

Figure 5.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) assessed by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy (IF-ANA) staining patterns demonstrated for the 38 patients that had undergone renal biopsy divided according to the WHO classification for lupus nephritis.

Discussion

The use of IF microscopy to identify ANAs was introduced by Holman, Kunkel and Friou already in the 1950s,40 41 and still remains the gold standard for ANA diagnostics.9 42 Different IF-ANA staining patterns arise depending on the nuclear antigens targeted and, to some extent, the nuclear staining patterns can have diagnostic implications.10 13 Being an exceptionally heterogeneous disease entity, different SLE phenotypes may associate with different ANA subspecificities. Nevertheless, studies on IF-ANA staining patterns in relation to SLE subtypes are very scarce. Thus, herein we asked if the IF-ANA staining pattern of well-characterised patients with SLE in a regional Swedish register per se contain any valuable clinical information. No corrections for multiple comparisons were made, but by reporting the exact p values this can easily be performed with a preferred method.43

In a previous investigation based on South Swedish patients with SLE who had all been judged IF-ANA positive at the time-point of diagnosis, a considerable proportion (24%) lost their ANA positivity over time.8 This may appear surprising, but our findings are very consistent with the results from a recent clinical trial for belimumab in SLE.44 Our study demonstrated that, among those remaining IF-ANA positive over time, the vast majority (62%) displayed H-ANA±other pattern, whereas fewer had a pure S-ANA pattern (10%). In the present study, we confirmed that H-ANA is the most common IF-ANA pattern among Swedish patients with SLE regardless of the number of fulfilled ACR criteria. The fact that we did not find any significant difference between ANA staining patterns in patients fulfilling the ACR-82 classification criteria and those that only met Fries’ criteria probably reflects that the ACR-82 criteria have a lower sensitivity and fail to identify all patients with ‘clinical SLE’ and at least two typical organ manifestations.

Many have dealt with differences in ANA fine-specificity and grouped patients according to ANA seroprofiles in order to reveal potential associations with defined clinical lupus manifestations.17–20 22–24 27–31 45 46 Using the luciferase immunoprecipitation system, Ching et al24 recently reported that the anti-Sm/snRNP-cluster was more associated with serositis than with the anti-SSA/SSB-cluster. Thompson et al22 observed that SLE cases with anti-dsDNA and/or anti-Sm were more likely to have malar rash, hypocomplementemia, renal and haematological involvement than patients without these autoantibodies. Our finding of a significant association between anti-Ro/SSA and photosensitivity was expected since several studies reported that patients who are anti-Ro/SSA positive have an increased rate of lupus-related rash and photosensitivity.22 27 29 However, in other studies the correlation between anti-Ro/SSA and skin disease has been less clear.19 47–49

In a recent and very large study from China, 1928 patients with SLE from five different centres were studied according to serological profiles.50 The presence of anti-dsDNA was found to be associated with renal disorder, serositis and haematological involvement. In our study, anti-dsDNA was exclusively associated with renal disorder. Only 15% of the Chinese lupus cohort exhibited the anti-Sm/snRNP/phospholipid-cluster, but these patients had the highest frequency of malar rash, oral ulcers, arthritis and serositis.50 As expected, skin disease/photosensitivity was associated with the anti-SSA/SSB-cluster, but contrasting to our findings Li et al reported a positive association between anti-SSA and arthritis. The reason for the contradictory findings may be sought in differences in methodology as well as in genetic factors.

Organ damage is strongly connected to SLE prognosis,51 52 but only one biomarker (osteopontin) has so far been shown to predict organ damage.53 In the present study, organ damage (SDI ≥1) was significantly less common among patients with S-ANA. This is a novel finding which calls for confirmation by others. A plausible explanation is that anti-dsDNA antibodies were also less common among cases with S-ANA and, given the strong association between anti-dsDNA and lupus nephritis,15 16 20 patients with S-ANA may have less (or at least milder) renal disease with a subsequent risk of developing organ damage. Another possible explanation is the well-documented association between anti-SSA/SSB and milder disease manifestations, for example, lupus-related rash and photosensitivity.22 27 29 Importantly, however, anti-SSA antibodies are not visualised on standard HEp-2 cells (used in this study) since the antigen levels are low.

To conclude, the results of this study demonstrate that IF-ANA staining patterns have some clinical correlates of potential diagnostic and prognostic interest in addition to traditional antigen-specific immunoassays. The findings that arthritis and signs of organ damage were less often associated with S-ANA compared with other staining patterns call for confirmatory studies and further elaborations, including identification of ANA fine-specificities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank research nurse Marianne Peterson and all the clinicians for their efforts.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF was involved in conception and design of the study, data collection and manuscript writing. ÖD contributed with statistical advice, interpretation of data and drafted the paper. AK was involved in acquisition of patient data, interpretation of data, intellectual discussion and manuscript writing. TS was involved in the laboratory work, interpretation of data, intellectual discussion and drafted the paper. CS contributed to the original idea, patient characterisation, interpretation of data, intellectual discussion and manuscript writing.

Funding: The study was financed by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the County Council of Östergötland, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, the Swedish Rheumatism Association, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Professor Nanna Svartz foundation, the King Gustaf V 80-year foundation, and the research foundation in memory of Ingrid Asp.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The regional ethics committee in Linköping, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lateef A, Petri M. Unmet medical needs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14(Suppl 4):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2008;358:929–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahle C, Skogh T, Åberg AK, et al. Methods of choice for diagnostic antinuclear antibody (ANA) screening: benefit of adding antigen-specific assays to immunofluorescence microscopy. J Autoimmun 2004;22:241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sjöwall C, Sturm M, Dahle C, et al. Abnormal antinuclear antibody titers are less common than generally assumed in established cases of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1994–2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon DH, Kavanaugh AJ, Schur PH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of immunologic tests: antinuclear antibody testing. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:434–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Mühlen CA, Tan EM. Autoantibodies in the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;5:323–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariz HA, Sato EI, Barbosa SH, et al. Pattern on the antinuclear antibody-HEp-2 test is a critical parameter for discriminating antinuclear antibody-positive healthy individuals and patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahler M, Fritzler MJ. The clinical significance of the dense fine speckled immunofluorescence pattern on HEp-2 cells for the diagnosis of systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Dev Immunol 2012;2012:494356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritzler MJ. Clinical relevance of autoantibodies in systemic rheumatic diseases. Mol Biol Rep 1996;23:133–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ter Borg EJ, Horst G, Hummel EJ, et al. Measurement of increases in anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels as a predictor of disease exacerbation in systemic lupus erythematosus: a long-term, prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:634–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanaugh AF, Solomon DH; American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Immunologic Testing Guidelines Guidelines for immunologic laboratory testing in the rheumatic diseases: anti-DNA antibody tests. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:546–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isenberg DA, Manson JJ, Ehrenstein MR, et al. Fifty years of anti-ds DNA antibodies: are we approaching journey's end? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1052–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winfield JB, Brunner CM, Koffler D. Serologic studies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and central nervous system dysfunction. Arthritis Rheum 1978;21:289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janwityanuchit S, Verasertniyom O, Vanichapuntu M, et al. Anti-Sm: its predictive value in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 1993;12:350–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CL, Ooi L, Wang F. Prevalence and clinical significance of antibodies to ribonucleoproteins in systemic lupus erythematosus in Malaysia. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alba P, Bento L, Cuadrado MJ, et al. Anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm antibodies and the lupus anticoagulant: significant factors associated with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:556–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benito-Garcia E, Schur PH, Lahita R, et al. Guidelines for immunologic laboratory testing in the rheumatic diseases: anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibody tests. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:1030–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson D, Juby A, Davis P. The clinical significance of autoantibody profiles in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 1993;2:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman IE, Peene I, Meheus L, et al. Specific antinuclear antibodies are associated with clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1155–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ching KH, Burbel PD, Tipton C, et al. Two major autoantibody clusters in systemic lupus erythomatousus. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e32001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, et al. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brouwer R, Vree Egberts WT, Hengstman GJ, et al. Autoantibodies directed to novel components of the PM/Scl complex, the human exosome. Arthritis Res 2002;4:134–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med 1982;97:664–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson MJ, Peebles CL, McMillan R, et al. Fluorescent antinuclear antibodies and anti-SSA/Ro in patients with immune thrombocytopenia subsequently developing systemic lupus erythomatousus. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:548–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mond CB, Peterson MG, Rothfield NF. Correlation of anti-Ro antibody with photosensitivity rash in systemic lupus erythomatousus patients. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:202–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baer AN, Maynard JW, Shaikh F, et al. Secondary Sjögren's syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus defines a distinct disease subset. J Rheumatol 2010;37:1143–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franceschini F, Cavazzana I. Anti-Ro/SSA and La/SSB antibodies. Autoimmunity 2005;38:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritzler MJ, Hanson C, Miller J, et al. Specificity of autoantibodies to SS-A/Ro on a transfected and overexpressed human 60 kDa Ro autoantigen substrate. J Clin Lab Anal 2002;16:103–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buyon JP, Clancy RM, Friedman DM. Autoimmune associated congenital heart block: integration of clinical and research clues in the management of the maternal / foetal dyad at risk. J Intern Med 2009;265:653–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oke V, Wahren-Herlenius M. The immunobiology of Ro52 (TRIM21) in autoimmunity: a critical review. J Autoimmun 2012;39:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enocsson H, Wetterö J, Skogh T, et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor levels reflect organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Transl Res 2013;162:287–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fries JF, Holman HR. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinical analysis. In: Smith LH. ed. Major problems in internal medicine. Philadelphia, London, Toronto W.B: Sauners, 1975:8–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fries JF. Methodology of validation of criteria for SLE. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 1987;65:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:363–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock RJ. Renal disease: classification and atlas of glomerular diseases 2nd edn New York: Igaku-Shoin, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holman HR, Kunkel HG. Affinity between the lupus erythematosus serum factor and cell nuclei and nucleoprotein. Science 1957;126:162–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friou GJ. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic significance and methods. Arthritis Rheum 1967;10:151–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meroni PL, Schur PH. ANA screening: an old test with new recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1420–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proschan MA, Waclawiw MA. Practical guidelines for multiplicity adjustment in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 2000;21:527–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace DJ, Stohl W, Furie RA, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1168–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hochberg MC, Boyd RE, Ahearn JM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of clinico-laboratory features and immunogenetic markers in 150 patients with emphasis on demographic subsets. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:285–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.To CH, Petri M. Is antibody clustering predictive of clinical subsets and damage in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:4003–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boey ML, Peebles CL, Tsay G, et al. Clinical and autoantibody correlations in Orientals with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 1988;47:918–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutej PG, Gear AJ, Morrison RC, et al. Photosensitivity and anti-Ro (SS-A) antibodies in black patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Br J Rheumatol 1989;28:321–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paz ML, González Maglio DH, Pino M, et al. Anti-ribonucleoproteins autoantibodies in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Relation with cutaneous photosensitivity. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:209–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li PH, Wong WH, Lee TL, et al. Relationship between autoantibody clustering and clinical subsets in SLE: cluster and association analyses in Hong Kong Chinese. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:337–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll T, Seifert B, Isenberg DA. SLICC/ACR Damage Index is valid, and renal and pulmonary organ scores are predictors of severe outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:248–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahman P, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. Early damage as measured by the SLICC/ACR damage index is a predictor of mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2001;10:93–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rullo OJ, Woo JM, Parsa MF, et al. Plasma levels of osteopontin identify patients at risk for organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.