Abstract

Background

Increasing physical activity (PA) levels among the general adult population of developed nations is important for reducing premature mortality and the burdens of preventable illness. Assessing how effective PA interventions are as health interventions often involves categorising participants as either ‘active’ or ‘sedentary’ after the interventions. A model was developed showing that doing this could significantly misestimate the health effect of PA interventions.

Methods

A life table model was constructed combining evidence on baseline PA levels with evidence indicating the non-linear relationship between PA levels and all-cause mortality risks. PA intervention scenarios were modelled which had the same mean increase in PA but different levels of take-up by people who were more active or more sedentary to begin with.

Results

The model simulations indicated that, compared with a scenario where already-active people did most of the additional PA, a scenario where the least active did the most additional PA was around a third more effective in preventing deaths between the ages of 50 and 60 years. The relationship between distribution of PA take-up and health effect was explored systematically and appeared non-linear.

Conclusions

As the health gains of a given PA increase are greatest among people who are most sedentary, smaller increases in PA in the least active may have the same health benefits as much larger PA increases in the most active. To help such health effects to be assessed, PA studies should report changes in the distribution of PA level between the start and end of the study.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Health Economics, Public Health, Social Medicine, Sports Medicine, Statistics & Research Methods

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We illustrate some problems with binary classification of physical activity (PA), and how these problems can make it difficult to know the clinical effectiveness of interventions which seek to raise PA.

We also describe a mathematical modelling approach which can be used to avoid these problems.

Our modelling approach does not use the best available evidence on the relationship between PA levels and health outcomes, and should be adapted to incorporate such evidence.

Introduction

The health consequences of sedentary lifestyles on preventable disease and premature mortality mean encouraging more physical activity (PA) is a public health priority.1–6 Evaluations of PA interventions often predefine PA thresholds, categorising people as ‘sedentary’, where increased mortality and morbidity risks are assumed, or ‘active’, where they are not; they are then assessed on how effective they are at moving people from the former to the latter category.7–10 However, these thresholds can be misleading because PA is a continuous variable and the relationship between PA increases and mortality/morbidity risk decreases is non-linear, and so depends on baseline PA levels.11–13 Evaluations which do not take account of these factors could draw the wrong conclusions about the health benefits of such interventions.

Trends and consequences of physical inactivity

Within high-income countries such as England, there has not only been a long-term upwards trend in leisure-time PA, but also a long-term downwards trend in workplace PA, which coupled with trends of rising levels of obesity hints at an overall downwards trend in PA.14–17 In recent years, there have been a number of studies of interventions to increase and maintain PA.17–22

Use of stratification by baseline activity levels in reporting PA interventions

Stratifying populations to describe the relationship between PA level and excess mortality or morbidity risks is misleading as it assumes homogeneity of risks between individuals within the same stratum, and so assumes that all people in the same category share the same risks.23 The fewer the strata used, the stronger and more inappropriate this assumption becomes, and is worst when levels of PA are dichotomised as ‘active’ or ‘sedentary’. When the real relative risk (RR) variation in a single stratum could be very large, assuming homogeneous risk in the stratum is inappropriate.11 24 25

Aim

In this paper, we develop a model to explore the relationship between baseline activity levels and the health consequences of a range of interventions which lead to the same mean increase in PA, but different levels of take-up of PA among people who were either more active, or less active, before the intervention. Differences in the health consequences of these interventions indicate the importance of representing inactivity as a continuous rather than as a categorical quantity.

Methods

Overview of method

A mathematical model was built to simulate the health effects of PA increases in a cohort of 50-year-olds. In one scenario, all members of the cohort increased their activity levels by the same amount, and in other scenarios either the least active or the most active increased their activity the most. Different levels of PA had different RRs of all-cause mortality. Increasing PA thus reduces the mortality risk, resulting in fewer expected deaths between the ages of 50 and 60 years. As the relationship between RR and activity level is non-linear, the number of lives saved by a PA intervention depends on the underlying distribution of PA levels after the intervention, not just the mean increase or the proportion of a cohort meeting a particular target. The three scenarios are constructed to illustrate this point, and involve identical mean increases in PA. Further details are provided in the online supplementary appendix.

Sources of data

Three sources of data are used. A baseline distribution of adult PA levels, reported as the mean minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day, was estimated from accelerometry data provided by adult working age participants in the 2008 Household Survey for England (HSE); the RRs of mortality associated with different PA levels were estimated from an epidemiological study; and unadjusted all-cause mortality rates were estimated from the UK life tables.24 26–28 Further details are provided in the online supplementary appendix.

Simulating variable rates of increase in PA

The amount of additional PA people performed following the intervention was varied according to the baseline level of PA. In the model, gains in PA were skewed so that either the least active or the most active did most of the additional activity. A skew parameter τ was constructed, allowing both the direction and degree of skew to be controlled. Negative τ values indicate a distribution favouring the least active, positive τ values indicate a distribution favouring the most active and a τ value of 0 represents the scenario in which all participants gain equally.

Levels of skewness considered

The main results show the expected number of deaths between the ages of 50 and 60 years in scenarios where the mean increase in MVPA per day was set to 10 min, and τ was set to –0.15 (the least active do most of the additional MVPA), 0.15 (the most active do most of the additional MVPA) and 0.0 (symmetrical). A secondary analysis was conducted in which the same mean increase was assumed and the degree of skew was varied over the range τ=−0.20 to τ=0.20.

Results

Simulated redistributions of PA levels

Figure 1 presents four histograms, plotted on the same scale, and with a vertical line marking a 30 min MVPA per day threshold, similar to the officially recommended target of 30 min MVPA for at least 5 days a week.17 The top left histogram, figure 1A, shows the baseline distribution of MVPA. The distribution is heavy tailed, with a concentration of people who do relatively little exercise, and less than the 30 min target, and a significant minority of more physically active individuals who greatly exceed the target, including around one-eighth of the sample who do at least double the MVPA target. The skewedness of the distribution is indicated by a median value slightly below the 30 min target (27.3), but a mean value slightly above the 30 min target (33.1).

Figure 1.

Distributions of physical activity (PA) levels in people aged 25–60 years in England. The black dashed line indicates the 30 min moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) target. (A) Levels observed in the Health Survey for England 2008; (B) a scenario where all participants do 10 min more MVPA per day; (C) a scenario where the mean increase in PA is 10 min/day, but people who did the least PA to start with gained the most; (D) a scenario where the mean increase in PA is also 10 min/day, but people who did the most PA to start with gained the most.

Figure 1B–D presents the distributions resulting from three different scenarios. In each of these scenarios, no one did less PA, and the mean increase compared with baseline (figure 1A) was the same (an additional 10 min MVPA). In figure 1B, the gains in additional PA were equally distributed for everyone, so that each person did 10 min more MVPA after than before the intervention; this is evident by noting that figure 1B is essentially figure 1A, but shifted slightly to the right. Figure 1C,D make the assumption that the amount of additional PA people perform is a function of how much PA they performed initially.

Simulated health implications in each scenario

Table 1 shows the results of simulations using the four scenarios shown above. In the baseline condition a, the mean MVPA is 33.1, as reported above. In the three comparator scenarios—b, c and d—the mean MVPA values are all 43.1, showing that the method used to adjust the distribution of PA increases according to the baseline PA levels did not cause any significant error or bias to the results. Owing to how increases in PA are distributed, the proportions of people meeting the 30 min target differed slightly in each comparator scenario, ranging from 61.1% meeting the target in the right-skewed scenario to 64.6% in scenario b.

Table 1.

Simulated effect of different distributions of additional PA on estimated numbers of deaths between the ages of 50 and 60 years in a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 people

| Scenario | (a) Baseline | (b) Equal: all gain equally | (c) Least active gain most | (d) Most active gain most |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean daily MVPA | 33.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 | 43.1 |

| Proportion meeting 30-min target (%) | 45.7 | 63.6 | 64.6 | 61.1 |

| Estimated deaths per 100 000 between ages of 50 and 60 | ||||

| Males | 8434 | 5333 | 5030 | 5832 |

| Females | 5642 | 3505 | 3302 | 3843 |

| Lives ‘saved’ by intervention per 100 000 between ages of 50 and 60 | ||||

| Males | N/A | 3101 | 3404 | 2602 |

| Females | N/A | 2137 | 2340 | 1799 |

MVPA, moderate or vigorous physical activity; PA, physical activity.

Rows four and five of table 1 present, respectively, the number of men and women expected to die between the ages of 50 and 60, in each case from a cohort of 100 000. In the baseline scenario, 8434 of 100 000 men, and 5642 of 100 000 women, died over this 10-year period. In scenario b, where all participants increased their PA levels by the same amount, 5030 of 100 000 men, and 3302 of 100 000 women, died over this same period of time, so in this scenario the intervention ‘saves’ around 3100/100 000 men, and around 2100/100 000 women.

In scenario c, 5030 deaths/100 000 men, and 3302 deaths/100 000 women, are predicted. Conversely, in scenario d, 5832 deaths/100 000 men, and 3843 deaths/100 000 women, are predicted. The differences in the estimates of the numbers of ‘lives saved’, shown in the bottom two rows of table 1, show that how increases in PA are distributed can affect how effective the interventions are in improving public health. In scenario c, around 10% more people are saved than in the equal increase scenario (9.8% more men and 9.5% more women). By contrast, in scenario d, approximately 16% fewer lives are saved than in the equal increase scenario (16.1% fewer men and 15.8% fewer women). In scenario c, the intervention is thus around one-third more effective than in scenario d.

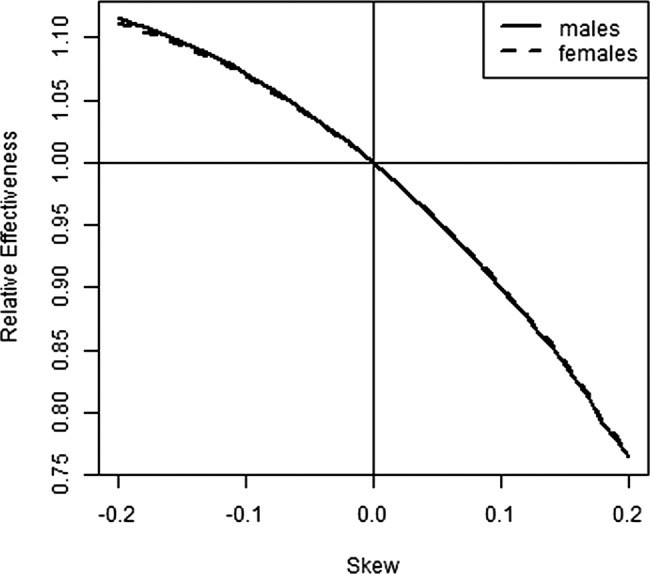

Effect of skewness on relative effectiveness

The relationship between the degree of skewness and the effectiveness of an intervention in reducing deaths is explored systematically in figure 2. The horizontal axis plots the skew, and the vertical axis plots the relative effectiveness (RE) of the intervention, in terms of the number of lives saved over the 10-year period simulated, compared with the scenario in which there was no skew (τ=0). Scenario c is equivalent to τ=−0.15, and scenario d is equivalent to τ=0.15. An RE of 1.10 means that 10% more lives were saved compared with the symmetric scenario, whereas an RE of 0.90 means 10% fewer lives were saved compared with the no-skew scenario. The results are presented separately for men and women, although the relationship is almost identical for both genders.

Figure 2.

Relationship between effectiveness of a physical activity (PA) intervention and degree of skewness, compared with the symmetric scenario (skew=0). The degree of skewness relates to the direction and magnitude of gain in PA relative to the symmetric scenario where all participants are assumed to perform the same amount of additional moderate or vigorous physical activity.

The results in figure 2 indicate that the RE of the intervention is greater than the equal increment (symmetric) scenario where the skew value is negative. RE increases with the magnitude of skew (distance from τ=0.0), but with diminishing returns, as the curve becomes flatter the further left the curve moves from skew=0. Following the curve rightwards from the skew=0 line, RE reduces as the skew magnitude increases as a moderate positive skew (τ=0.1) reduces RE by around 10%, whereas a moderate negative skew of the same magnitude (τ=−0.1) increases RE by about 7%. This asymmetry may be due in part to a decision to cap the maximum RR associated with sedentary PA levels to 10. However, the asymmetry appears plausible as increasing PA levels among the most physically active are likely to lead to only marginal increases in public health, because they reduce annual mortality risks only slightly, in absolute terms, as the mortality rates for this subgroup were already very low.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This paper described the results of a simple simulation model which took account of the relationship between the PA and RR of all-cause mortality to simulate the number of lives that might be saved by public health interventions which increase PA. We found that, though interventions may seem similarly effective at encouraging people to be more active, how much these increases in PA lead to better health depends on the baseline activity levels of those who increased their PA levels. In particular, it illustrated that people who are least active to begin with are likely to have most to gain from a marginal increase in PA, but for people who are already moderately or highly active, the additional health gains for the same marginal increase in PA are likely to be more modest.

Limitations

The continuous relationship between relative PA and relative mortality risk had to be estimated using results of a study which reported RRs by a different but related measure, exercise capacity. This was of a US-based study of men, and so the further assumption was made that the estimated relationship also applied to women. This study was used in preference to results from the systematic review by Woodcock and colleagues because it presented the relationship by an exercise quintile, allowing straightforward centring of the RR relative to persons doing ‘typical’ levels of PA. However, systematically derived estimates should be used if developing this model for predictive purposes. A relatively arbitrary decision was made to cap the maximum estimated RR relating to very low activity at 10 in order to produce relatively conservative estimates of the positive effects of boosting activity in the most inactive. The estimated baseline distribution of PA levels was based on a large sample of observations from the HSE drawn from a wide age range, which may be a limitation if PA distributions change a lot with the age group. The measure of PA level used from the HSE 2008 database, MVPA, depends on how the moderate activity threshold level was defined.26 No data sources were identified using a rigorous systematic review process due to resource constraints.

Relationship with previous findings and research

Economic models which involve representing PA in categorical rather than continuous terms are commonplace.7 9 29 However, they may not be appropriate for estimating the impact of public health interventions, where the underlying condition is continuous, and the consequences nonlinear. Recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on the public health benefits of walking and cycling to work is based on a model which represents the mortality risk continuously rather than discretely; the above results suggest this is good practice.30 A recent systematic review also confirmed the importance of the baseline activity level in estimating the impact on mortality of changes in activity level, and by extension the impact of interventions to increase activity levels.31

Implications for research

Further research should assess how sensitive the estimates of the model are to the data sources used and technical assumptions made. Additional data sources should be sought through extensive consultation with clinical experts and identified through systematic reviews. Following this process, the model could be developed to estimate, for example, how much more commissioners of PA interventions should consider paying to achieve a given increase in activity in very sedentary compared with less sedentary populations, due to the additional health benefits the most sedentary receive. Further research could also estimate the effects on morbidity outcomes as well as mortality, indicating the potential cost-savings to the National Health Service of successful PA interventions. An implication of this model for the presentation of results of PA trials is that researchers should consider reporting increases in PA by baseline PA level, as otherwise the health implications of reported increases in activity are unclear. To develop the model to accurately predict public health policy implications, parameters identified through systematic review and meta-analysis, such as those presented by Woodcock and colleagues, should be used in place of the existing parameters. The model also suggests that it would be very useful for cohort studies to use standardised methods for measuring PA, as otherwise it can be difficult to assess whether RRs based on these cohorts are non-comparable due to the different baseline PA levels.

The use of stratification (or dichotomisation) of activity levels in analyses of the relationship between sedentary lifestyle and morbidity or mortality risks is very common.19 We strongly argue against the use of stratification (or categorisation) and use non-linear models to describe the relationship between risk and exposure. The resulting curves or splines from these models could also provide further justification for categorisation if the risk is reasonably constant within certain intervals.

Implications for clinical practice

The main significance of these findings for public health practice and for PA practitioners is the rationale and evidence base they provide for making decisions about population groups and individuals to target for specific intervention programmes. There is some evidence that the most sedentary individuals and communities will find it more difficult to get more active than those who already have a great degree of physical fitness and experience of the feasibility of being more active and of the immediate physical, mental and social potential benefits of PA.32 Recent epidemiological studies show that occupational and household energy expenditure tends to greatly exceed sports-based energy expenditure in working age adults.33 As a moderate level of PA may be required to actively participate in and enjoy many forms of sports-based activity, interventions aiming to produce small increases in activity in the most sedentary, such as improving the built environment to encourage walking, may be more effective for this population than sports-based interventions.34

Conclusion

The results of this mathematical model highlight the importance of representing PA levels along a continuum, and representing the risks associated with different levels of PA as a continuous rather than categorical quantity. They indicate that modest increases in PA among the least active may confer similar or greater health benefits than greater increases in PA among people who are more physically active. Although it is important that more active people remain active, the model indicates that it is also important to recognise that PA interventions targeted at the most inactive may be effective at improving health even if they bring modest PA increases. In order to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a PA intervention, studies should report changes in the distribution of PA level rather than proportions moving from predefined ‘sedentary’ or ‘active’ PA categories.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JM and EG developed the idea for the manuscript. JM created the model. MD advised on model development. EE-H, ES and EG reviewed and summarised the existing relevant research. EE-H, MD and EG each led on writing first drafts for specific sections of the manuscript. JM wrote all other sections of the manuscript and collated material by the other authors. All authors contributed to later revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (grant number HTA 07/25/02).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The R script developed to perform the analyses described in this paper is included as an appendix.

References

- 1.NICE Four commonly used methods to increase physical activity. 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11373/31838/31838.pdf

- 2.Donaldson L. At least five a week: Evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. A report from the Chief Medical Officer. 2004. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4080981.pdf

- 3.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012;55:2895–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fogelholm M. Physical activity, fitness and fatness: relations to mortality, morbidity and disease risk factors. A systematic review. Obes Rev 2010;11:202–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, et al. Estimating the current and future costs of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabetic Med 2012;29:855–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill J. Preventing type 2 diabetes: a role for every practitioner. Community Pract 2012;85:34–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beale S, Bending M, Trueman P. An Economic Analysis of Environmental Inverventions that Promote Physical Activity. 2007

- 8.Elley CR, Garrett S, Rose SB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of exercise on prescription with telephone support among women in general practice over 2 years. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1223–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MATRIX Modelling the cost effectiveness of physical activity interventions. 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/FourmethodsEconomicModellingReport.pdf

- 10.Bucksch J. Physical activity of moderate intensity in leisure time and the risk of all cause mortality. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:632–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen LB, et al. All-cause mortality associated with physical activity during leisure time, work, sports, and cycling to work. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown WJ, McLaughlin D, Leung J, et al. Physical activity and all-cause mortality in older women and men. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:664–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samitz G, Egger M, Zwahlen M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40: 1382–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis E, Ekelund U, Wareham NJ. Temporal trends in physical activity in England: the Health Survey for England 1991 to 2004. Prev Med 2007;45:416–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380:247–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juneau C-E, Potvin L. Trends in leisure-, transport-, and work-related physical activity in Canada 1994-2005. Prev Med 2010;51:384–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Start Active, Stay Active A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. 2011. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_128210.pdf

- 18.Hind D, Scott EJ, Copeland R, et al. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness evaluation of “booster” interventions to sustain increases in physical activity in middle-aged adults in deprived urban neighbourhoods. BMC Public Health 2010;10:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orrow G, Kinmonth A-L, Sanderson S, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012;344:e1389–e1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, et al. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD007651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker PR, Francis DP, Soares J, et al. Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(4):CD008366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillsdon M, Foster C, Thorogood M. Interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennette C, Vickers A. Against quantiles: categorization of continuous variables in epidemiologic research, and its discontents. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, et al. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 2002;346:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokkinos P, Sheriff H, Kheirbek R. Physical inactivity and mortality risk. Cardiol Res Pract 2011;2011:924945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig R, Mindell J, Hirani V. Health Survey for England 2008: Volume 2: Methods and documentation. 2009. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/HSE/HSE08/Volume_2_Methods_and_Documentation.pdf (accessed 30 Oct 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers J, Kaykha A, George S, et al. Fitness versus physical activity patterns in predicting mortality in men. Am J Med 2004;117: 912–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Office for National Statistics Interim Life Tables: Summaries UK interim Life Tables, 1980-82 to 2008-10. 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lifetables/interim-life-tables/2008-2010/sum-ilt-2008-10.html (accessed 29 Sep 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrett S, Elley CR, Rose SB, et al. Are physical activity interventions in primary care and the community cost-effective? A systematic review of the evidence. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e125–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan A, Blake L, Hill-McManus D, et al. Walking and cycling: local measures to promote walking and cycling as forms of travel or recreation: Health economic and modelling report. 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13428/58985/58985.pdf

- 31.Woodcock J, Franco OH, Orsini N, et al. Non-vigorous physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:121–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogerson MC, Murphy BM, Bird S, et al. “I don't have the heart”: a qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators of physical activity for people with coronary heart disease and depressive symptoms. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratzlaff CR. Good news, bad news: sports matter but occupational and household activity really matter—sport and recreation unlikely to be a panacea for public health. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:699–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NICE Promoting and creating built or natural environments that encourage and support physical activity. London, 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11917/38983/38983.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.