Abstract

Objective

Hospital-acquired pneumonia remains the most lethal and expensive nosocomial infection worldwide. Optimal therapy remains controversial. We aimed to compare mortality and clinical response outcomes in patients treated with either linezolid or vancomycin.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, American College of Physicians Journal Club, Evidence-based Medicine BMJ and abstracts from infectious diseases and critical care meetings were searched through April 2013.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

All randomised clinical trials comparing linezolid to vancomycin for hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Data extraction

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines were followed. One author extracted the data and two authors rechecked and verified all data.

Results

Nine randomised trials with a total of 4026 patients were included. The adjusted absolute mortality risk difference (RD) between linezolid and vancomycin was 0.01% (95% CI −2.1% to 2.1%; p=0.992; I2=13.5%. The adjusted absolute clinical response difference was 0.9% (95% CI −1.2% to 3.1%; p=0.409; I2=0%. The risk of both microbiological (RD=5.6%, 95% CI −2.2% to 13.3%; p=0.159; I2=0%) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (RD=6.4%, 95% CI −4.1% to 16.9%; p=0.230; I2=0%) eradication were not different between linezolid and vancomycin. Gastrointestinal side effects were more frequent with linezolid (RD=0.8% (95% CI 0% to 1.5%; p=0.05), but no differences were found with renal failure, thrombocytopenia and drug discontinuation due to adverse events. Our sample size provided 99.9% statistical power to detect differences between drugs regarding clinical response and mortality.

Conclusions

Linezolid and vancomycin have similar efficacy and safety profiles. The high statistical power and the near-zero efficacy difference between both antibiotics demonstrates that no drug is superior for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Keywords: INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Linezolid and vancomycin have similar efficacy and safety profiles.

The near-zero efficacy difference between both antibiotics demonstrates that no drug is superior for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Our results remained consistent across different patient populations and study designs for both clinical response and mortality outcomes.

Randomised controlled trials set selective inclusion criteria that can limit their generalisability to unselected populations.

Introduction

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) remains among the most frequent type of infection acquired in intensive care unit settings1 2 and is associated with substantial mortality, ranging from 15 to 57%.3 Gram-positive organisms, mainly Staphylococcus aureus, cause approximately one-third of these pneumonias.3 4

The optimal antibiotic therapy for the treatment of HAP caused by Gram-positive organisms is controversial.5–7 Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been performed comparing linezolid to glycopeptides for the treatment of HAP.8 9 The conclusions of both meta-analyses were similar and consistent: clinical cure and survival were equivalent for linezolid, vancomycin and teicoplanin. However, new randomised trials have been published since these meta-analyses, the most recent of which concluded that linezolid is superior to vancomycin.10 This has reawakened controversy regarding the optimal therapy for Gram-positive HAP.

There are important public health reasons to resolve the controversy regarding the optimal treatment for Gram-positive HAP. A perceived difference in clinical efficacy is likely to drive increased usage of one agent versus the other with consequent risk of unintended consequences. In the case of linezolid, these include increased risk of outbreaks of linezolid resistant organisms, higher total drug costs and adverse drug events such as serotonin syndrome in patients with interacting medications and cytopenias in patients treated with prolonged courses.11 In the case of vancomycin, these include increased risk of clinical failure if the drug is underdosed, increased risk of nephrotoxicity if the drug is overdosed and central venous catheter complications such as bloodstream infections and thromboembolic disease.12

In light of the renewed controversy and public health significance regarding optimal treatment for Gram-positive HAP, we present the largest systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy and safety of linezolid versus vancomycin incorporating these new studies. Our study has long-term implications for two reasons: (1) the cumulative number of patients and events now available for analysis (4026) allow close to 100% statistical power to detect a difference in mortality outcome between these two treatments, that is, it is unlikely that any future trial would add clinically meaningful information, and (2) the manufacturer (Pfizer) does not plan to perform any more randomised trials with either drug.13

Material and methods

Literature search

A systematic literature search was independently performed through April 2013 in MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library by a professional librarian (Dr Cynthia Schmidt) and by one of the authors (AK). Any disagreement was resolved by a consensus. We also searched abstracts published in the same time period from the following meetings: Society of Critical Care Medicine, Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chest, and American Thoracic Society. Relevant Internet sites such as the Food and Drug Administration reports and trial results repositories (http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org and http://www.clinicaltrialresults.org) were also searched. The keywords used were: linezolid, oxazolidinone, vancomycin, glycopeptide, Staphylococcus, Gram-positive, infections, randomised, prospective, lungs, respiratory, hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated and nosocomial pneumonia. No language restrictions were used. This study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Study selection

Randomised clinical trials that compared linezolid to vancomycin for the treatment of HAP were included in our analysis. Trials that did not use vancomycin as the comparator were excluded. Also excluded were articles not containing original research (eg, narrative reviews, editorials and case reports).

Data extraction

The following variables were abstracted and collected in a standardised form: authors, publication year, study design, gender, mean age, sample size, site of infection, microorganism species and susceptibility, clinical response, microbiological eradication, mortality and adverse events. For studies that included multiple sites of infection, we extracted data only from the patient population with HAP. Any disagreement was resolved by further review of the study and consensus among authors.

Efficacy and safety outcome definitions

Primary efficacy outcomes (1) mortality was defined as an all-cause 28-day mortality reported by each study and (2) clinical response was defined at the test of cure evaluation (TOC) or at the follow-up visit (FUV) for the clinically evaluable population. If TOC data were not available, then clinical response at the last study follow-up was used. Secondary efficacy outcomes: (1) microbiological eradication was defined as documented eradication of all Gram-positive organisms at TOC for the microbiologically evaluable population. If TOC data were not available, then microbiological eradication at the last study follow-up was used. (2) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) eradication was defined as documented eradication of MRSA within the microbiologically evaluable population. (3) Safety: gastrointestinal events included nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, hepatitis and pancreatitis; renal failure and thrombocytopenia were defined as reported by the authors of each paper. Study drug discontinuation was defined as the permanent discontinuation of either linezolid or vancomycin due to an adverse event.

Statistical analysis

All results were reported with the random-effects model. The Q statistic method was used to assess statistical heterogeneity and the I-squared (I2) statistic was used to evaluate the inconsistency between trials.14 15 All absolute risk difference estimates were pooled by using the DerSimonian and Laird methodology.16 We choose the risk difference over the risk ratio in order to better describe the direct clinical effects of our findings. The quality of each trial was evaluated by the Jadad criteria. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines17 for reporting meta-analysis were followed. All analyses were adjusted for the study design to account for potential ascertainment bias. The software used was Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA). Egger regression and Begg and Mazumdar18 methods were used to evaluate publication bias. Statistical power calculations were performed based on the comparison of two independent proportions by χ2 testing using the software Power and Precision V.4.0 (Englewood, New Jersey, USA). The two-group test of proportions was used to test the null hypothesis that the proportion of cases meeting the primary outcome was identical in the two groups. Hierarchy was not accounted for because the τ was 0, which indicated that the power based on either fixed-effect or random-effects modelling produced exactly the same results.15

Results

A total of nine trials met the inclusion criteria10 19–26 (figure 1) with a total sample size of 4026 patients. Study characteristics are presented in table 1, and quality of evidence is presented in the online supplementary data.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow of randomised controlled trials.

Table 1.

Randomised trials characteristics

| Study, year | Total sample size | Mean age (linezolid/vancomcyin) | Type of infection | Intubation (%) at baseline (linezolid/vancomycin) | Mean days of therapy (linezolid/vancomycin) | Linezolid arm (Gram-negative coverage) | Vancomycin arm (Gram-negative coverage) | Primary outcome | Jadad score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubinstein E (2001)20 | 396 | 63/61 | Hospital-acquired pneumonias | 57.1/57.5 | 9.6/8.9 | Linezolid+aztreonam | Vancomycin+aztreonam | CR and ME at TOC | 4 |

| Stevens DL (2002)21 | 460 | 64/60 | MRSA infections, including hospital-acquired pneumonias | NR/NR | 12.6/11.3 | Linezolid+aztreonam or gentamicin | Vancomycin+aztreonam or gentamicin | CR and ME at TOC | 3 |

| Kaplan SL (2003)22 | 316 | 2.2/2.9 | Gram-positive infections, including hospital-acquired pneumonias | NR/NR | 11.3/12.2 | Linezolid+aztreonam or gentamicin | Vancomycin+aztreonam or gentamicin | CR and ME at TOC | 3 |

| Wunderink R (2003)23 | 623 | 63/62 | Hospital-acquired pneumonias | NR/NR | 9.5/9.4 | Linezolid+aztreonam | Vancomycin+aztreonam | CR and ME at TOC | 3 |

| Jaksic B (2006)24 | 605 | 48/47 | Neutropenic fever, including hospital-acquired pneumonias | NR/NR | 11.4/11.5 | Linezolid+Gram-negative coverage | Vancomycin+Gram-negative coverage | CR and ME at TOC | 4 |

| Kohno S (2007)25 | 151 | 68/67 | MRSA infections, including hospital-acquired pneumonias | NR/NR | 10.9/10.6 | Linezolid+aztreonam or gentamicin | Vancomycin+aztreonam or gentamicin | CR and ME at TOC | 3 |

| Wunderink R (2008)26 | 149 | 56/55 | MRSA hospital-acquired pneumonias | 100/100 | 10.8/11.5 | Linezolid+Gram-negative coverage | Vancomycin+Gram-negative coverage | CR and ME at FUV | 3 |

| Lin D (2008)19 | 142 | 56.3/59.6 | Gram-positive infections, including hospital-acquired pneumonias | 5.6/11.3 | 12.2/10.7 | Linezolid+aztreonam | Vancomycin+aztreonam | CR at FUV and EOT | 3 |

| Wunderink R (2012)10 | 1184 | 60.7/61.6 | MRSA hospital-acquired pneumonias | 60.5/66.5 | 10/10 | Linezolid+Gram-negative coverage | Vancomycin+Gram-negative coverage | CR at EOS | 4 |

CON, control; CR, clinical response; EOT: end of therapy; EOS, end of study; FUV, follow-up visit; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; ME, microbiological eradication; NR, not reported; TRE, treatment; TOC, test of cure visit.

Efficacy analyses

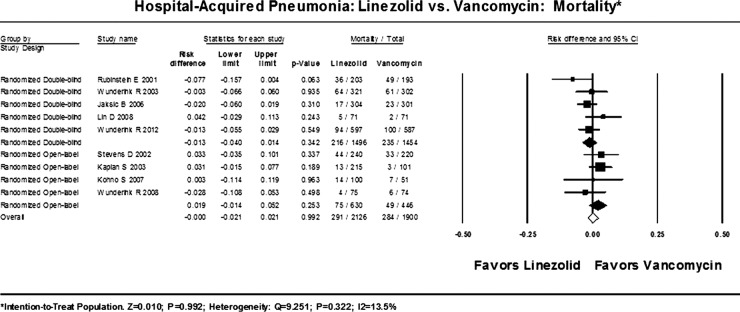

Mortality

The absolute risk difference (RD) between linezolid and vancomycin for 28-day all-cause mortality based on the intention-to-treat population (N=4026) was 0.0001 (95% CI −0.021 to 0.021; p=0.992; I2=13.5%; figure 2).

Figure 2.

All-cause mortality.

Clinical response

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for clinical response based on the intention-to-treat population (N=3637) was 0.009 (95% CI −0.012 to 0.031; p=0.409; I2=0%; figure 3A). The RD between linezolid and vancomycin for clinical response based on the clinically evaluable and per protocol population (N=1161) was 0.037 (95% CI −0.019 to 0.092; p=0.192; I2=0%; figure 3B). The clinical response on the per protocol population with MRSA infection only (N=507) showed an RD=0.077 (95%CI −0.008 to 0.162; p=0.076).

Figure 3.

(A) Clinical response—intention-to-treat population, (B) clinical response—per protocol population.

Microbiological eradication

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for microbiological eradication based on the microbiologically evaluable and per protocol population (N=600) was 0.056 (95% CI −0.022 to 0.133; p=0.159; I2=0%; figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) Microbiological eradication—per protocol population, (B) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus eradication—per protocol population.

MRSA eradication

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for MRSA eradication based on the microbiologically evaluable and per protocol population (N=416) was 0.064 (95% CI −0.041 to 0.169; p=0.230; I2=0%; figure 4B).

Safety analyses

Gastrointestinal events

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for gastrointestinal events based on the intention-to-treat population (N=3421) was 0.008 (95% CI −0.000 to 0.015; p=0.050; I2=78%; figure 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Gastrointestinal events, (B) Thrombocytopenia.

Thrombocytopenia

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for thrombocytopenia based on the intention-to-treat population (N=3421) was 0.008 (95% CI −0.003 to 0.020; p=0.161; I2=74%; figure 5B).

Renal failure

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for renal failure based on the intention-to-treat population (N=3421) was −0.007 (95% CI −0.018 to 0.005; p=0.249; I2=48%; figure 6A).

Figure 6.

(A) Renal failure, (B) study drug discontinuation due to adverse events.

Drug discontinuation due to adverse events

The absolute RD between linezolid and vancomycin for drug discontinuation based on the intention-to-treat population (N=3421) was −0.005 (95% CI −0.016 to 0.007; p=0.424; I2=0%; figure 6B).

Sensitivity analyses

The trial by Jaksic et al24 was the only study that included patients with leukaemia, active chemotherapy treatment and several other nephrotoxic antibiotics such as amphotericin and aminoclycosides; since these factors can cause major gastrointestinal events (eg, graft vs host disease, mucositis, Clostridium difficile colitis), thrombocytopenia (eg, disease-induced or drug-induced bone marrow suppression) and renal failure (eg, chemotherapy-induced or antibiotic-induced), this study was not included in the prospectively planned side-effect analyses. However, its inclusion to these analyses did not change any of the original results. The trial by Kaplan et al22 was the only one that included paediatric population only; the removal of this study from all analyses did not alter our results (data not shown); similarly the removal of the oldest trial by Rubinstein et al also did not change the results. The trials by Jaksic,24 Stevens,21 Lin,19 and Kohno25 included mortality for other sites of infection; their removal did not change the overall results. The trial by Wunderink et al10 was the only one that did not provide 28-day mortality (only 60-day mortality)—its removal from the mortality analysis did not change the original findings (RD=0.006 (95% CI −0.019 to 0.031); p=0.649; I2=21%). An analysis based on the type of Gram-negative coverage produced similar results. The analyses based on the quality of studies by Jadad scores showed the following: 28-day mortality: Jadad ≤3: RD=0.019 (95% CI −0.008 to 0.046); p=0.18; I2=0%; Jadad >3: RD=−0.024 (95% CI −0.051 to 0.004); p=0.10; I2=0%. Clinical response: Jadad ≤3: was 0.019 (95% CI −0.054 to 0.093); p=0.612; I2=0%; Jadad >3: RD=0.04 (95% CI −0.058 to 0.138); p=0.426; I2=30%.

Power calculations

Mortality: Based on a prospectively planned expected mortality rate at least 5% lower (95% CI −7% to −3%) with linezolid, and a control mortality rate of 15%, the sample size of our intention-to-treat meta-analysis (N=2000 in each arm) has 99.9% power to detect a mortality difference of 5% with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-tailed).

Clinical response: Based on a prospectively planned expected clinical response rate at least 10% higher (95% CI 4% to 16%) with linezolid, and a control clinical response of 57%, the sample size of our intention-to-treat meta-analysis (N=2000 in each arm) has 99.9% power to detect a clinical response difference of 10% with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-tailed).

Publication bias analyses

Mortality outcome: No publication bias was detected by Egger regression (intercept=−0.038; SE=1.236; p=0.976), or by Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation (Kendall's τ <0.0001; p=1.000).

Clinical response outcome: No publication bias was detected by Egger regression (intercept=−0.790; SE=0.762; p=0.334), or by Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation (Kendall's τ −0.027; p=0.917).

Discussion

Our primary outcome analysis demonstrates that linezolid and vancomycin are similar with respect to mortality reduction and clinical response. Our findings are robust and clinically meaningful based on the high statistical power to detect outcome differences between these two drugs—100% power for both mortality and clinical response, and the near zero heterogeneity for all efficacy analyses.

Importantly, all analyses included only randomised trials and accounted for the differences in study design, which make the potential for selection and ascertainment biases less likely. In addition, the clinical response analyses showed no differences between both drugs in the intention-to-treat as well as the per protocol patient populations. Moreover, the clinical response in the per-protocol patients with MRSA pneumonia likewise did not show differences between drugs. Our secondary efficacy outcomes were also in agreement with our primary outcomes; both microbiological eradication and MRSA eradication were not different between vancomycin and linezolid. Even though microbiological outcomes are not necessarily as meaningful as survival and clinical response, the absence of significant microbiological outcomes lends further support to the results of our primary clinical and survival analysis.

Our efficacy findings are also in agreement with two previous meta-analyses8 9 that evaluated these antibiotics to treat HAP, and two other meta-analyses27 28 that evaluated these drugs and other antibiotics in patients with multiple sites of infection, including pneumonias. Consistency between the current meta-analysis and prior analyses despite being performed by different research groups using different statistical methods adds further credence to our findings.

Our conclusions are contrary to those of Wunderink et al10 whose recent clinical trial concluded that linezolid has superior clinical efficacy compared to vancomycin. Closer examination of this trial, however, helps to reconcile their results with our meta-analysis. Of the 1184 participants randomised into the Wunderink et al study, only 339 (28%) were included in the clinical efficacy analysis. Excluding 72% of all randomised patients undermined the balancing of potential confounders conferred by randomisation. Not surprisingly, there were notable differences between the linezolid and vancomycin groups: patients treated with vancomycin had higher rates of mechanical ventilation, bacteraemia, diabetes, renal failure and heart failure; and the levels of vancomycin were suboptimal in half of the patients enrolled in the trial biasing against clinical success with vancomycin. The authors claimed linezolid superiority based on their per protocol analysis but there was no significant difference in clinical response or mortality in the intention-to-treat analysis. Of note, the CONSORT29 and ICH guidelines30 recommend intention-to-treat analyses for all clinical trials. Nonetheless, our meta-analysis shows that even if one combines only the per-protocol patients from all available trials comparing linezolid versus vancomycin (figure 3B), the pooled results including data from 1161 per-protocol patients still do not show an advantage with linezolid. Last, it was stated in the report by Wunderink et al10 that Pfizer had the power to override the clinical outcomes as determined by the investigators, but no details regarding the reasons or extent of overriding were provided.

We found few differences in the drugs’ side effect profiles. The most significant difference was found with respect to gastrointestinal events, which were more frequent with linezolid, while thrombocytopenia was numerically, but not significantly higher despite linezolid's well-known predilection to cause bone marrow suppression. Differences in definitions of thrombocytopenia used in the studies may have led to the high-observed heterogeneity and may have precluded the detection of this side effect with linezolid. The lack of difference could, however, also be explained on clinical grounds: usual treatment courses for pneumonia may be too short to realise the time-dependent risk of thrombocytopenia and vancomycin itself can also cause thrombocytopenia. Renal failure may be associated with vancomycin, but it was not significantly more frequent in patients treated with vancomycin compared with linezolid in our meta-analysis. Definitions of renal failure did vary among studies, and may explain the high heterogeneity for this analysis, but the very small difference in renal failure rates (0.7%) among 3421 patients makes a significant difference unlikely. The lack of difference may also reflect the more ‘healthy-patient’ inclusion biases of randomised controlled trials. Finally, the comparable rates of study drug discontinuation due to adverse events (figure 6B) further affirms a minimal difference in the safety profiles between vancomycin and linezolid.

Limitations of our study follow from limitations in the source trials. Randomised controlled trials set selective inclusion criteria that can limit their generalisability to unselected populations. None of the studies specifically focused on MRSA with higher vancomycin minimum-inhibitory concentrations nor did any of the studies utilise continuous vancomycin infusion. Some of the trials were open-label studies leading to potential ascertainment bias for clinical endpoints; however, the results of our analyses remained consistent when stratified by the presence or absence of blinding. The traditional limitation of a lack of power to detect mortality differences from individual trials on HAP is no longer a concern as our meta-analysis included approximately 4000 patients and allowed close to 100% power to detect a mortality or clinical response difference, thereby conferring a high degree of confidence that there are no advantages for either drug. The heterogeneity was substantial for both gastrointestinal events and thrombocytopenia; however, the lack of differences and low heterogeneity seen within the study drug discontinuation due to adverse events analysis supports our overall findings of a similar safety profile between drugs.

In conclusion, similar efficacy and safety profiles show that both vancomycin and linezolid are equivalent in patients with HAP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Ashley Calhoon for providing administrative support and Dr Cynthia Schmidt for the library support. Institutional Review Board: Exempted.

Footnotes

Contributors: AK was involved in conception and design of the study. AK and MR were involved in collection of the data. AK and GH were involved in statistical analysis. AK, MK, GH and MR were involved in analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the article and critical revision for important intellectual content. AK, MK, GH and MR approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. AK is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MR research grants from 3M and Molnlycke in the form of contracts to the University of Nebraska Medical Center, and advisory board/consultant/honoraria from 3M, Bard, Molnlycke, Artise.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:388–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev 1993;6:428–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:867–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the united states. JAMA 2007;298:1763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunderink RG, Rello J, Cammarata SK, et al. Linezolid vs vancomycin: analysis of two double-blind studies of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1789–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powers JH, Ross DB, Lin D, et al. Linezolid and vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: the subtleties of subgroup analyses. Chest 2004;126:314–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalil AC, Puumala SE, Stoner J. Unresolved questions with the use of linezolid vs vancomycin for nosocomial pneumonia. Chest 2004;125:2370–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalil AC, Murthy MH, Hermsen ED, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin or teicoplanin for nosocomial pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1802–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walkey AJ, O'Donnell MR, Wiener RS. Linezolid vs glycopeptide antibiotics for the treatment of suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest 2011;139:1148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis 2012;64:621–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez Garcia M, De la Torre MA, Morales G, et al. Clinical outbreak of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit. JAMA 2010;303:2260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kullar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, et al. Impact of vancomycin exposure on outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfizer Report New phase 4 study shows higher rates of clinical and microbiological success for zyvox versus vancomycin in MRSA nosocomial pneumonia. 2010;2013 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. Power analysis for meta-analysisIntroduction to meta-analysis. 1st edn John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:1119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin DF, Zhang YY, Wu JF, et al. Linezolid for the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive pathogens in china. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008;32:241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubinstein E, Cammarata S, Oliphant T, et al. Linezolid Nosocomial Pneumonia Study Group. Linezolid (PNU-100766) versus vancomycin in the treatment of hospitalized patients with nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens DL, Herr D, Lampiris H, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:1481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan SL, Deville JG, Yogev R, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin for treatment of resistant gram-positive infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wunderink RG, Cammarata SK, Oliphant TH, et al. Linezolid Nosocomial Pneumonia Study Group. Continuation of a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of linezolid versus vancomycin in the treatment of patients with nosocomial pneumonia. Clin Ther 2003;25:980–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaksic B, Martinelli G, Perez-Oteyza J, et al. Efficacy and safety of linezolid compared with vancomycin in a randomized, double-blind study of febrile neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohno S, Yamaguchi K, Aikawa N, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Japan. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60:1361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wunderink RG, Mendelson MH, Somero MS, et al. Early microbiologic response to linezolid versus vancomycin in ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Chest 2008;134:1200–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falagas ME, Siempos II, Vardakas KZ. Linezolid versus glycopeptide or beta-lactam for treatment of gram-positive bacterial infections: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beibei L, Yun C, Mengli C, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of gram-positive bacterial infections: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010;35:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006;295:1152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ICH Expert Working Group ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: statistical principles for clinical trials. 1998 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.