Abstract

Objectives

We investigated the prevalence and long-term risk associated with intracranial atherosclerosis identified during routine evaluation.

Design

This study presents data from a prospective cohort of patients admitted to our stroke unit for thrombolysis evaluation.

Setting and participants

We included 652 with a final diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) from April 2009 to December 2011. All patients were acutely evaluated with cerebral CT and CT angiography (CTA). Acute radiological examinations were screened for intracranial arterial stenosis (IAS) or intracranial arterial calcifications (IAC). Intracranial stenosis was grouped into 30–50%, 50–70% and >70% lumen reduction. The extent of IAC was graded as number of vessels affected.

Primary and secondary outcome measure

Patients were followed until July 2013. Recurrence of an ischaemic event (stroke, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and TIA) was documented through the national chart system. Poor outcome was defined as death or recurrence of ischaemic event.

Results

101 (15.5%) patients showed IAS (70: 30–50%, 29: 50–70% and 16: >70%). Two-hundred and fifteen (33%) patients had no IAC, 339 (52%) in 1–2 vessels and 102 (16%) in >2 vessels. During follow-up, 53 strokes, 20 TIA and 14 IHD occurred, and 95 patients died. The risk of poor outcome was significantly different among different extents of IAS as well as IAC (log-rank test p<0.01 for both). In unadjusted analysis IAS and IAC predicted poor outcome and recurrent ischaemic event. When adjusted, IAS and IAC independently increased the risk of a recurrent ischaemic event (IAS: HR 1.67; CI 1.04 to 2.64 and IAC: HR 1.22; CI 1.02 to 1.47).

Conclusions

Intracranial atherosclerosis detected during acute evaluation predicts an increased risk of recurrent stroke.

Keywords: STROKE MEDICINE

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The high degree of generalisability due to the unselected patient population.

The consistent use of CT-angiography (CTA).

The acute CTA performance that might lead to an underestimation of the true prevalence of intracranial arterial stenosis due to thrombus formation.

Introduction

Ischaemic stroke remains a leading cause of disability and death worldwide, and one of six persons suffers a stroke during their lifetime. Intracranial atherosclerosis represents a risk factor of stroke, however, varying incidence and significance worldwide have been reported.1–6 Even though intracranial arterial atherosclerosis is traditionally assumed most prevalent in patients of Asian descent, limited evidence is available as to the prevalence and prognostic significance of intracranial atherosclerosis in a European stroke population.

Overall, two markers of intracranial atherosclerotic changes are recognised on CT-based imaging of patients with stroke: intracranial arterial stenosis (IAS) and diffused intracranial arterial calcifications (IAC).

IAS has in recent years received much attention in relation to possible treatment interventions, especially with regard to endovascular procedures7 and pharmacological treatment.8 Though most attention has been focused on stenosis with severe lumen reduction, postmortem studies have shown that even lumen reductions of 30% can potentially give rise to embolism or thrombus.9 This finding indicates that patients with 30% stenosis could potentially be at increased risk of recurrent stroke.

IAC is assumed to reflect the atherosclerotic burden and can be assessed by means of simple non-contrast CT.10 11 Even though these lesions do not necessarily cause lumen reduction and may represent a more diffused atherosclerotic process—limited evidence suggests their link to recurrent ischaemic events in patients with stroke.12

Because intracranial atherosclerosis may represent an important and potentially modifiable risk factor for recurrent ischaemic events in an European stroke population, we aimed at (1) establishing the incidence of IAS and calcifications in an acute northern European thrombolysis population identified during acute radiological examination; (2) identifying potential modifiable risk-factors; and (3) assessing whether intracranial atherosclerosis identified during acute stroke evaluation predicts poor long-term outcome.

Methods

This study is based on a prospective cohort of stroke or patients with transient ischaemic attack (TIA) admitted to Copenhagen University Hospital—Bispebjerg with symptoms of acute stroke within 4.5 h and worked up for recanalisation therapy. The hospital has a catchment area for acute stroke of 1.7 million inhabitants on even dates, sharing the function with another hospital.

Patients admitted from April 2009 to December 2011 with a CT angiography (CTA) of diagnostic quality on admission and a discharge diagnosis of stroke or TIA were prospectively included in the cohort.

On arrival, all patients underwent physical and neurological examination, and the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was obtained along with standard biochemistry, ECG and vital values. All patients underwent non-contrast CT—and in patients without contra indications, CTA was performed. Intravenous thrombolysis was administered according to general guidelines. In all non-thrombolysed patients with stroke or TIA, 300 mg of aspirin was administered.

Radiological imaging

Acute CT scans were performed using 64-section MDCT (Philips Brilliance 64 TM; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with non-contrast CT cerebrum (120 kVp, 500 mAs; 5 mm slice thickness reconstruction). CTA was performed from aortic arch to vertex (120 kVp, 295 mAs; collimation 64×0.625 mm (isotropic voxel resolution)) with contrast injection, Omnipaque 350 mg/mL, 5 mL/s, monitored by bolus tracking in the descending aorta and scanned with fixed 3 s post-tracking delay (0.9 mm slice reconstruction).

All images during the study period were reviewed by a consultant neuroradiologist (AFC) blinded to all clinical data using a standardised method. Thoracocervicale and intracranial arteries from the aortic arch and cranially were evaluated. An extracranial carotid artery stenosis was considered significant, if a lumen reduction >70% was demonstrated.

All major intracranial vessels, (internal carotid artery, anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery (MCA), posterior cerebral artery, basilar artery (B) and vertebral artery (V)) were screened for stenosis stratified into three categories of lumen reduction (30–50%, 50–70% and >70%) in accordance with standard WASID criteria for grading of IAS.13 We defined percentage of stenosis of an intracranial artery as follows Percentage of

where D (stenosis) is the diameter of the artery at the site of the most severe stenosis and D (normal) is the diameter of the proximal normal artery.13 If the proximal segment was diseased, contingency sites were chosen to measure D (normal): distal artery (second choice) or feeding artery (third choice). IAS was graded as symptomatic, if supplying a vascular area with radiological signs of acute ischaemia and no other obvious cause (eg, acute occlusion) was present.

We employed a semiquantitative score for the number of vessels calcified according to a presence or absence of calcified foci.12

Data extraction and definitions

Data were prospectively collected from all patients on a daily basis from charts and by direct interview. All previous concurrent medical conditions (stroke/TIA, ischaemic heart disease (IHD), congestive heart failure and periphery artery disease) were confirmed by registrations in previous medical charts.

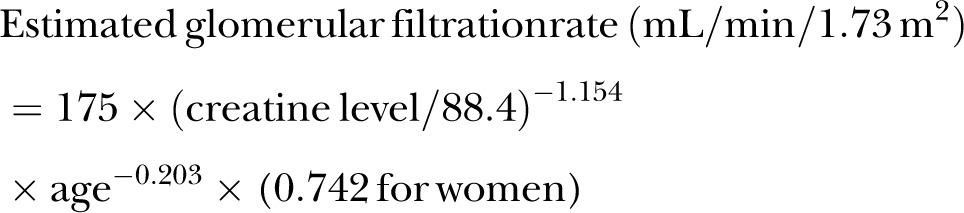

Hypertension was defined as either use of antihypertensive medication or at least three blood pressure measurements above 140/90 mm Hg taken at least 1 h apart and at least 24 h after stroke onset—or a diagnosis of hypertension in the outpatient clinic. Diabetes was defined as use of antidiabetic medication, or a fasting glucose >9 mmol/L—or glycosylated haemoglobin >6.5%. Hypercholesterolaemia was defined as use of lipid-lowering medication—or plasma cholesterol > 5 mmol/L. IHD was defined as prior myocardial infarction or prior coronary by-pass surgery—or prior percutaneous coronary intervention. Atrial fibrillation was defined as a history of atrial fibrillation or at least 30 s of atrial fibrillation documented by telemetry or ECG in 12 leads. A history of smoking was defined as present use of tobacco in any form or a smoking history of at least 3 pack-years. Excessive use of alcohol was defined as consumption of more than 250 g alcohol/week for men and 170 g for women. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated on the basis of the creatine-level14

|

Follow-up

Prior to discharge, all patients with ischaemic stroke or TIA were prescribed an antiplatelet treatment regimen (clopidogrel—or aspirin and dipyridamole in combination). Patients with diagnosed atrial fibrillation were prescribed oral anticoagulation treatment, mainly warfarin, but dabigatran was used in some cases. All patients with thrombotic stroke were prescribed a statin and antihypertensives aiming at a maximum systolic value of 130 mm Hg.

All patients were followed up after discharge through the national online chart system until 1 July 2013. Recurrent event was defined as ischaemic stroke, TIA or IHD as documented by discharge cards. Recurrent stroke or TIA were considered present, if diagnosed by radiographic imaging studies, or if a consultant neurologist in the patient's discharge card confirmed the diagnosis. Recurrent IHD was defined as either ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-STEMI (NSTEMI) diagnosed by ECG change or enzyme level increase, unstable angina pectoris, coronary by-pass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention. Poor outcome was defined as either recurrent event or death within the follow-up period.

Statistics

No formal sample size calculations were performed. The patient flow in the study period determined the sample size.

Categorical data were compared among groups using χ2 test. Ordinal or discrete risk factors were represented using median values and compared using Mann-Whitney U test. If variables were normally distributed, they were compared using Student’s’ t test, otherwise a non-parametric alternative (Mann-Whitney U test) was used. Missing values were excluded from the calculations.

To assess the association between risk factors and the presence of intracranial atherosclerosis, a multinomial logistic regression model was used. All risk factors from table 2 that proved a group difference of p<0.1 were entered in a backward stepwise multinomial logistic regression.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics between groups

| IAS | No IAS | p Value | IAC | No IAC | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 72.6 (11.9) | 66.0 (14.3) | <0.0001 | 71.7 (11.2) | 57.7 (14.9) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 65 (62%) | 303 (55%) | 0.200 | 252 (57%) | 116 (54%) | 0.452 |

| Index stroke | ||||||

| Ischaemic | 82 (78%) | 409 (74%) | 0.462 | 340 (77%) | 151 (70%) | 0.068 |

| TIA | 23 (22%) | 142 (26%) | 101 (23%) | 64 (30%) | ||

| NIHSS, units | 5 (2–11) | 4 (2–9) | 0.141 | 4 (2–9) | 3 (1–8) | 0.013 |

| Onset until CTA, minutes | 155.4 (120.6) | 148.5 (118.0) | 0.655 | 148.7 (100.9) | 151.4 (148.3) | 0.115 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Stroke | 27 (26%) | 91 (17%) | 0.026 | 95 (22%) | 23 (11%) | 0.001 |

| TIA | 12 (12%) | 39 (7.1%) | 0.159 | 39 (8.9%) | 12 (5.6%) | 0.163 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 22 (21%) | 56 (10%) | 0.003 | 69 (16%) | 9 (4.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 9 (8.7%) | 23 (4.2%) | 0.076 | 29 (6.6%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0.003 |

| Stroke risk factors | ||||||

| Hypertension | 85 (81%) | 312 (57%) | <0.0001 | 308 (70%) | 89 (42%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 11 (11%) | 46 (8.3%) | 0.453 | 47 (11%) | 10 (4.7%) | 0.011 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 79 (78%) | 333 (64%) | 0.008 | 294 (71%) | 118 (57%) | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 20 (19%) | 136 (25%) | 0.260 | 118 (27%) | 38 (18%) | 0.011 |

| Smoking history | 52 (53%) | 263 (51%) | 0.743 | 222 (54%) | 93 (48%) | 0.033 |

| Alcohol misuse | 16 (17%) | 60 (12%) | 0.176 | 63 (15%) | 13 (6.4%) | 0.002 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Cholesterol, mmol/L* | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 0.364 | 5.31 (1.1) | 5.32 (1.1) | 0.901 |

| LDL, mmol/L* | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.224 | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.737 |

| HDL, mmol/L* | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.812 | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.787 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L* | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.8) | 0.838 | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.516 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.5 (1.8) | 6.4 (2.0) | 0.116 | 6.5 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.1) | 0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 70.4 (20.4) | 77.8 (21.1) | 0.001 | 74.4 (21.6) | 81.2 (19.7) | <0.0001 |

| Radiological observations | ||||||

| Extracranial carotid stenosis | 20 (19%) | 48 (8.7%) | 0.003 | 60 (14%) | 8 (3.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Atherosclerotic carotid lesions | 80 (76%) | 251 (46%) | <0.0001 | 288 (65%) | 43 (20%) | <0.0001 |

| Atherosclerotic aorta lesions | 75 (71%) | 237 (43%) | <0.0001 | 275 (48%) | 37 (17%) | <0.0001 |

*Only patients not on prestroke statin treatment.

IAC, intracranial arterial calcifications; IAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; CTA, CT angiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NIHSS; National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

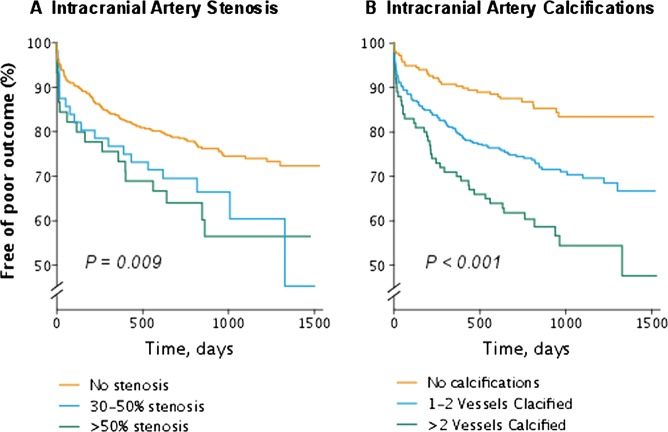

Survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meyer curves. In order to ensure sufficient group size in the Kaplan-Meier curves, we grouped 50–70% and >70% stenosis as >50%. Calcifications were grouped into three groups: one without and two groups with calcifications divided by the total median number of calcified arteries in the cohort. We conducted univariate Cox proportional hazard model analysis of characteristics in table 2 (not including medical history—stroke, TIA or myocardial infarction—due to potential interaction with other characteristics). We transferred characteristics that in the univariate model proved p<0.1 to the multivariate model. Patients lost to follow-up were censured the day they were lost. A general significance level of p<0.05 was employed. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.20 statistical software (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Study population

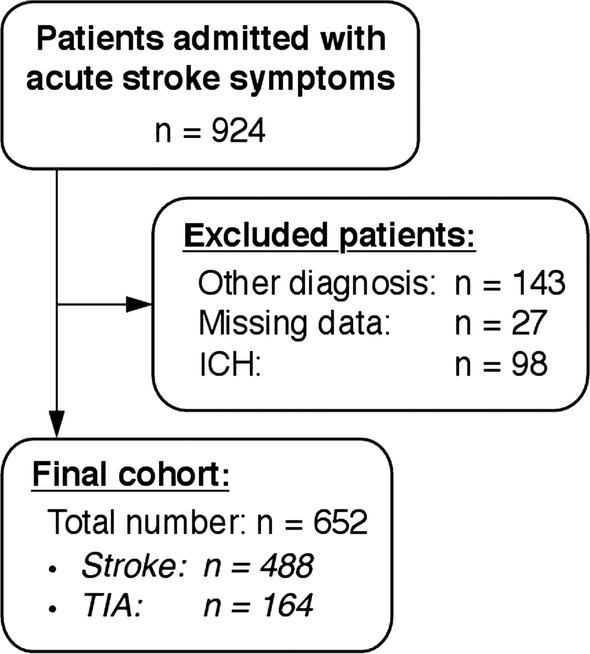

During the study period, 924 patients were admitted with acute stroke symptoms. The final population thus comprised 652 patients with ischaemic stroke or TIA (figure 1). Only 34 patients (5.2%) had other ethnicity than Scandinavian, of whom 3 (0.5%) were of Asian descent.

Figure 1.

Patient flow.

Prevalence of intracranial atherosclerosis

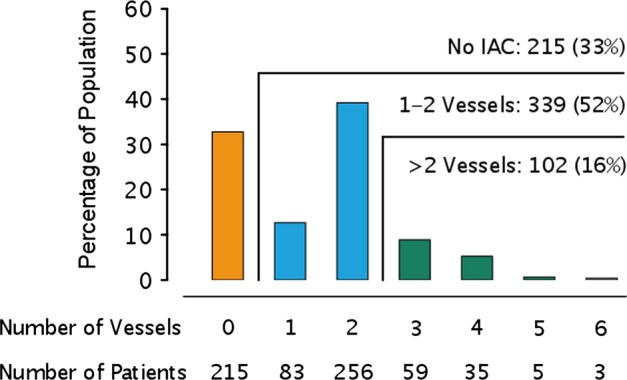

A total of 115 IAS were observed in 101 (15.5%) patients (table 1). Of these 45 (39%) had a severe lumen reduction of >50%. Only one patient underwent endovascular procedures with stenting of a >70% basilar artery stenosis. This patient remained in the cohort due to failure of revascularisation. Three patients had a symptomatic stenosis (all above 50% lumen reduction and all in the MCA). IAC in one or more vessels was observed in 441 (68%: figure 2), and median number of vessels involved was two. This number was used to group patients with moderate calcifications (1–2 vessels calcified) from patients with extensive lesions (>2 vessels calcified).

Table 1.

Prevalence of intracranial arterial stenosis

| Vascular segments | Degree of stenosis |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–50% | 50–70% | >70% | ||

| ICA | 18 (16%) | 6 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 26 (23%) |

| MCA | 17 (15%) | 17 (15%) | 8 (7%) | 42 (37%) |

| ACA | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) |

| PCA | 21 (18%) | 5 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 29 (25%) |

| Basilar | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 5 (4%) |

| Vertebral | 9 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (9%) |

| Total | 70 (61%) | 29 (25%) | 16 (14%) | 115 (100%) |

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; IAS: intracranial arterial stenosis ICA, internal carotid artery—in this context the intracranial segment; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of intracranial arterial calcifications graded by the number of calcified vessels.

Risk factors

Based on the baseline characteristics (table 2), a multinomial logistical regression was performed to determine the risk factor profile of IAC and IAS (table 3). Age was an independent predictor of IAC as well as IAS. In addition, atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta and former IHD were independent predictors in IAC as well as IAS. Hypertension, former stroke, hypercholesterolaemia and extracranial carotid stenosis were independent predictors of IAS (table 3).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression

| No lesions | IAS (≥30%) |

IAC (≥1 vessels) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1 | 2.08 | 1.54 to 2.82 | 1.56 | 1.56 to 2.38 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 1 | 2.62 | 1.36 to 5.05 | 1.49 | 0.95 to 2.34 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1 | 3.50 | 1.14 to 10.7 | 2.83 | 1.01 to 7.91 |

| Former stroke | 1 | 2.53 | 1.18 to 5.43 | 1.80 | 0.95 to 3.40 |

| Hypertension | 1 | 3.29 | 1.61 to 6.71 | 1.44 | 0.91 to 2.26 |

| Atherosclerotic aorta lesions | 1 | 4.88 | 2.45 to 9.75 | 3.86 | 2.28 to 6.54 |

| Extracranial carotid stenosis | 1 | 2.91 | 1.03 to 8.26 | 1.75 | 0.68 to 4.51 |

Atherosclerotic carotid lesions, eGFR and congestive heart failure were entered in the model.

Nagelkerke R2=0.40.

IAC, intracranial arterial calcifications; IAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Outcome after stroke

Of the 652 patients included in this analysis, 13 were lost to follow-up after hospital discharge—all foreign citizens, who had a stroke while visiting Copenhagen. The median (IQR) follow-up time was 815.5 days (607–1124 days). During the follow-up time, 87 ischaemic events were registered (53 strokes, 20 TIA and 14 IHD), and 95 patients died. Kaplan-Meier curves for poor outcome (death or ischaemic events) are presented in figure 3A,B. A significant difference in risk of poor outcome was present when stratified for the extent of both IAS as well as IAC (log-rank test p<0.01 in figure 3A and B). The probability of poor outcome past the first year after index event for patients with no IAS (0.16 CI 0.10 to 0.22) and no IAC (0.10 CI 0.03 to 0.22) was substantially lower than in patients with >50% IAS (0.27 CI 0.09 to 0.49) and >2 vessels IAC (0.30 CI 0.18 to 0.43). In crude estimates, both the burden of IAC (per vessels increase) and lumen reduction of any significant degree (IAS>30%) were associated with recurrent ischaemic events and poor outcome (table 4). When adjusted for other risk factors, the burden of IAC emerged as an independent predictor for recurrent event or death (HR 1.18; CI 1.03 to 1.36/vessel increase). If only recurrent ischaemic events (stroke, TIA and MI) were considered, both IAC and IAS emerged as independent risk factors for recurrent event (HR 1.67; CI 1.04 to 2.64 and HR 1.22; CI 1.02 to 1.47, respectively).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the proportion of patients alive and free of recurrent event. p Value indicates log-rank.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard model for the predictive value of stenosis and calcifications

| IAS (≥30%) |

IAC (per vessels) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Poor outcome (ischaemic event or death) | ||||

| Crude estimate | 1.73 | 1.21 to 2.48 | 1.41 | 1.26 to 1.58 |

| Adjusted estimate* | 1.25 | 0.86 to 1.81 | 1.18 | 1.03 to 1.36 |

| Ischaemic event alone: | ||||

| Crude estimate | 2.13 | 1.34 to 3.38 | 1.39 | 1.19 to 1.61 |

| Adjusted estimate† | 1.67 | 1.04 to 2.64 | 1.22 | 1.02 to 1.47 |

*Adjusted for age, NIHSS, mRS before stroke, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, extracranial carotid stenosis and atherosclerotic aorta lesions.

†Adjusted for age, hypertension, extracranial carotid stenosis and atherosclerotic aorta lesions.

IAC, intracranial arterial calcifications; IAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

Discussion

In this study, intracranial atherosclerosis was not an unusual finding in North European patients with ischaemic stroke and TIA. The process of developing atherosclerotic lesions seemed to be part of a global and time-dependent process of atherosclerotic development in the body, marked by progressing age along with accompanying lesions in the aortic arch and former myocardial infarction. In addition, more severe atherosclerotic lesions (lesions with lumen reduction—IAS) were linked to a more severe risk profile accompanied by extracranial carotid stenosis as well as traditional stroke risk factors as hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. We furthermore observed that the risk of a poor outcome increased with the burden of intracranial atherosclerotic disease being highest in patients with >50% IAS and >2 vessels IAC. Both IAS (>30%) and IAC burden were independently associated with risk of recurrent ischaemic event.

The primary strength of this study is the high degree of generalisability due to the unselected patient population. This cohort of unselected patients further allows us to compare consecutive patients with stroke or TIA with intracranial atherosclerosis against a control group comprised of similar patients with stroke or TIA without intracranial atherosclerosis. Further, our national online chart system made sure that all patients with permanent stay in Denmark could be followed up, and recurrent events could be assessed from discharge cards. Only patients not seeking medical help for recurrent events have been missed. Another important strength of this study is the consistent use of CTA in the population and the blinded standardised imaging evaluation.

The primary limitations of this study are that the true prevalence of IAS probably is underestimated due to the acute setting, in which the CTA was performed. IAS may have been mistaken as acute vascular occlusions due to superimposed thrombus. However, in the present study, the aim is to assess the impact of stenosis identified during acute evaluation and their implication and signal value on the prognosis of the patients.

CTA has been shown to process a sensitivity and specificity of 97– 99.5%, respectively in detecting IAS>50% compared to DSA and to be superior to MR angiography.15 16 A number of studies have used transcranial Doppler to detect stenosis. Although, transcranial doppler (TCD) is non-invasive and performs well in the middle-cerebral artery, it is highly observer dependent and has poor sensitivity and specificity in the posterior vasculature.17

It is known that the prevalence of intracranial atherosclerosis varies with ethnicity. In direct comparison between ethnic groups in the population of Manhattan, persons with Caucasian ancestry have a lower burden of large vessel disease compared to people of Hispanic and African-American descent.4 18 This is supported by studies reporting the prevalence of IAS to be as high as 30–50% in Asian stroke populations1 3 5 6 and 7–12% in asymptomatic populations.19 20 The incidence of documented symptomatic intracranial stenosis in populations of Europe is reported to be 2.2–6.5%.21–23 This number may represent the tip of the iceberg. A newer cross-sectional CTA-based study elaborated by Homburg et al2 revealed a prevalence of stenotic lesions of 23% (30–99% stenosis). Our finding of a prevalence of 15.5% is in accordance with Homburg et al revealing that intracranial atherosclerotic disease is a relevant and prevalent problem in European stroke population. The reason for this ethnic difference in prevalence is likely due to genetic and lifestyle differences between ethnic groups.

The direct comparison of the prevalence of IAC among studies is hampered by differences in the methods of quantifying its extent.11 24–26 However, IAC is likely to reflect atherosclerotic burden.10 11

Our finding that age is a risk factor for atherosclerotic disease is in accordance with almost all previous studies.2 11 19 24 26 27 It is likely that the process of atherosclerosis in the intracranial vasculatures is of a progressive nature and linked to ongoing atherosclerotic processes in other body parts.24 28 29 In this study, we identified hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia as risk factors for only IAS, and not IAC. This finding is not in accordance with other studies identifying especially hypertension as an important risk factor for IAC.26 However, we believe that the pooling of patients with various degrees of IAC—from patients with one vessel calcified and thus a weak risk-factor profile together with patients with more extensive IAC burden and thus a heavier risk factor profile—may have led to this conclusion.

In the present study, we were not able to identify diabetes as a risk factor for intracranial atherosclerosis. Diabetes is in general believed to be a risk factor for IAC and IAS.2 9 20 26 27 This finding may be due to ethnic differences in the incidence of diabetes.30

Prognostic studies of patients with IAS have predominantly been focusing on symptomatic lesions22 31 and thus contain an ill-fitting prognostic value on the general population with stroke with varying degrees of intracranial atherosclerosis and with a low prevalence of symptomatic stenosis. Studies on prognosis in more general populations with stroke have been performed in Asian patients with stroke with a much higher rate of IAS32 showing a clear link to recurrent ischaemic events.

In order to prevent further ischaemic events in patients with IAS, efforts as balloon angioplasty and stenting have been attempted. The recent SAMMPRIS trial found no benefit of stenting the intracranial stenotic lesions compared to aggressive medical therapy, especially due to an unacceptable rate of periprocedural complications.7 This finding is further supported by results from the WASID trial proposing that the recurrence rate in patients with symptomatic artery stenosis can be reduced by strict risk-factor modification.33 This suggests a possible beneficial effect of stricter risk factor control and aggressive medical prophylaxis in patients with lumen-reducing lesions IAS.

The prognostic value of IAC has only been investigated in a smaller single-centre study elaborated by Bugnicourt et al.12 This study found that IAC provided an independent risk factor for recurrent vascular event and death. This finding is supported by our data and indicates that the burden of IAC should be assessed as a factor in poststroke risk assessment similar to artery stenosis and atrial fibrillation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of radiological findings of intracranial atherosclerosis (IAS and IAC) detected during acute evaluation on recurrent vascular events and death in a large well-defined cohort of patients admitted within 4.5 h of stroke onset. With the results of the present study in hand, it seems that the problem of preventing recurrent ischaemia in patients with intracranial atherosclerosis is still very much alive.

In summary, this study shows that radiological markers of intracranial atherosclerosis are prevalent in North European patients with symptoms of acute stroke and appear linked to a global process of atherosclerotic disease. Our results suggest that intracranial atherosclerosis in consecutive patients with stroke or TIA entail a dramatic increase in risk of poor outcome compared to patients with stroke or TIA without intracranial atherosclerosis. Furthermore, IAS or IAC independently increases the risk of recurrent ischaemic events. So far, risk-factor modification and aggressive medical therapy remain first line treatments in this patient group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank nurses and doctors of the Department of Neurology, Bispebjerg University Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: CO designed the study, gathered data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. AA, CK, JKN and IH gathered data. AFC gathered data and interpreted the results. SR interpreted results. HC designed the study and interpreted the results.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CO holds research grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and from Eva and Henry Fraenkels Memorial Foundation. HC holds a research grant from the Capital Region of Denmark.

Ethics approval: The registry was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency file no. 2010-41-5205 in accordance with Danish law.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.De Silva DA, Woon FP, Lee MP, et al. South Asian patients with ischemic stroke: intracranial large arteries are the predominant site of disease. Stroke 2007;38:2592–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Homburg PJ, Plas GJ, Rozie S, et al. Prevalence and calcification of intracranial arterial stenotic lesions as assessed with multidetector computed tomography angiography. Stroke 2011;42:1244–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suri MF, Johnston SC. Epidemiology of intracranial stenosis. J Neuroimaging 2009;19(Suppl 1):11S–16S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation 2005;111:1327–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KS, Huang YN, Gao S, et al. Intracranial stenosis in Chinese patients with acute stroke. Neurology 1998;50:812–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong KS, Li H, Chan YL, et al. Use of transcranial Doppler ultrasound to predict outcome in patients with intracranial large-artery occlusive disease. Stroke 2000;31:2641–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:993–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1305–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Gongora-Rivera F, et al. Autopsy prevalence of intracranial atherosclerosis in patients with fatal stroke. Stroke 2008;39:1142–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassab MY, Gupta R, Majid A, et al. Extent of intra-arterial calcification on head CT is predictive of the degree of intracranial atherosclerosis on digital subtraction angiography. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:45–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohn YH, Cheon HY, Jeon P, et al. Clinical implication of cerebral artery calcification on brain CT. Cerebrovasc Dis 2004;18:332–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bugnicourt JM, Leclercq C, Chillon JM, et al. Presence of intracranial artery calcification is associated with mortality and vascular events in patients with ischemic stroke after hospital discharge: a cohort study. Stroke 2011;42:3447–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, et al. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:643–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:247–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bash S, Villablanca JP, Jahan R, et al. Intracranial vascular stenosis and occlusive disease: evaluation with CT angiography, MR angiography, and digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1012–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen-Huynh MN, Wintermark M, English J, et al. How accurate is CT angiography in evaluating intracranial atherosclerotic disease? Stroke 2008;39:1184–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rorick MB, Nichols FT, Adams RJ. Transcranial Doppler correlation with angiography in detection of intracranial stenosis. Stroke 1994;25:1931–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, et al. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke 1995;26:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong KS, Huang YN, Yang HB, et al. A door-to-door survey of intracranial atherosclerosis in Liangbei County, China. Neurology 2007;68:2031–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong KS, Ng PW, Tang A, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis in high-risk patients. Neurology 2007;68:2035–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Weitzel-Mudersbach P, Johnsen SP, Andersen G. Intra- and extracranial stenoses in TIA—findings from the Aarhus TIA-study: a prospective population-based study. Perspect Med 2012;1:207–10 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber R, Kraywinkel K, Diener HC, et al. Symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenoses: prevalence and prognosis in patients with acute cerebral ischemia. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;30:188–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weimar C, Goertler M, Harms L, et al. Distribution and outcome of symptomatic stenoses and occlusions in patients with acute cerebral ischemia. Arch Neurol 2006;63:1287–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen XY, Lam WW, Ng HK, et al. The frequency and determinants of calcification in intracranial arteries in Chinese patients who underwent computed tomography examinations. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006;21:91–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen XY, Lam WW, Ng HK, et al. Intracranial artery calcification: a newly identified risk factor of ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging 2007;17:300–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koton S, Tashlykov V, Schwammenthal Y, et al. Cerebral artery calcification in patients with acute cerebrovascular diseases: determinants and long-term clinical outcome. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:739–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Cancio E, Dorado L, Millan M, et al. The Barcelona-Asymptomatic Intracranial Atherosclerosis (AsIA) study: prevalence and risk factors. Atherosclerosis 2012;221:221–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bugnicourt JM, Chillon JM, Tribouilloy C, et al. Relation between intracranial artery calcifications and aortic atherosclerosis in ischemic stroke patients. J Neurol 2010;257:1338–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo WK, Yong HS, Koh SB, et al. Correlation of coronary artery atherosclerosis with atherosclerosis of the intracranial cerebral artery and the extracranial carotid artery. Eur Neurol 2008;59:292–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, et al. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: whites, blacks, hispanics, and asians. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2317–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazighi M, Tanasescu R, Ducrocq X, et al. Prospective study of symptomatic atherothrombotic intracranial stenoses: the GESICA study. Neurology 2006;66:1187–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong KS, Li H. Long-term mortality and recurrent stroke risk among Chinese stroke patients with predominant intracranial atherosclerosis. Stroke 2003;34:2361–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaturvedi S, Turan TN, Lynn MJ, et al. Risk factor status and vascular events in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Neurology 2007;69:2063–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.