Abstract

Objectives

The role vitamin D intake/production plays in sarcoidosis-associated hypercalcaemia is uncertain. However, authoritative reviews have recommended avoiding sunlight exposure and vitamin D supplements, which might lead to adverse skeletal outcomes from vitamin D insufficiency. We investigated the effects of vitamin D supplementation on surrogate measures of skeletal health in patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D insufficiency.

Design

Randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting

Clinical research centre.

Participants

27 normocalcaemic patients with sarcoidosis and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) <50 nmol/L.

Intervention

50 000 IU weekly cholecalciferol for 4 weeks, then 50 000 IU monthly for 11 months or placebo.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary endpoint was the change in serum calcium over 12 months, and secondary endpoints included measurements of calcitropic hormones, bone turnover markers and bone mineral density (BMD).

Results

The mean age of participants was 57 years and 70% were women. The mean (SD) screening 25OHD was 35 (12) and 38 (9) nmol/L in the treatment and control groups, respectively. Vitamin D supplementation increased 25OHD to 94 nmol/L after 4 weeks, 84 nmol/L at 6 months and 78 nmol/L at 12 months, while levels remained stable in the control group. 1,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D levels were significantly different between the groups at 4 weeks, but not at 6 or 12 months. There were no between-groups differences in albumin-adjusted serum calcium, 24 h urine calcium, markers of bone turnover, parathyroid hormone or BMD over the trial. One participant developed significant hypercalcaemia after 6 weeks (total cholecalciferol dose 250 000 IU).

Conclusions

In patients with sarcoidosis and 25OHD <50 nmol/L, vitamin D supplements did not alter average serum calcium or urine calcium, but had no benefit on surrogate markers of skeletal health and caused one case of significant hypercalcaemia.

Trial registration

This trial is registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au). The registration number is ACTRN12607000364471, date of registration 5/7/2007.

Keywords: THORACIC MEDICINE

Article summary.

Strength and limitations of the study

The study had limited power to detect small differences in bone density and bone turnover markers.

Few participants had 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels <25 nmol/L, and therefore the findings may not apply to individuals with very low vitamin D levels.

Introduction

Hypercalcaemia occurs commonly in sarcoidosis, with an estimated prevalence of 4–11%.1 2 Hypercalcaemia results from dysregulated production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25OHD) by activated macrophages in granulomata.3 Although the mechanism of hypercalcaemia is known, the role of vitamin D intake and production is less certain. On the one hand, cases of hypercalcaemia and sarcoidosis precipitated by sunlight exposure or vitamin D supplements have been reported,4–8 and there is a seasonal variation in 1,25OHD levels9 and the prevalence of hypercalcaemia.7 9 10 These findings suggest that increases in 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) levels through sunlight exposure or vitamin D intake contribute to hypercalcaemia. On the other hand, studies have reported no correlation between 25OHD, 1,25OHD and serum calcium;11 historical studies of treatment with very large doses of vitamin D (target 100 000 IU/day for 5–212 days) produced hypercalcaemia in only 4/24 patients,12 and patients with sarcoidosis and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis commonly take vitamin D supplements without developing hypercalcaemia.13 Furthermore, countries at higher latitudes do not have consistently lower prevalence of hypercalcaemia in sarcoidosis than countries closer to the equator,1 and prevalence of hypercalcaemia in sarcoidosis is similar in countries with and without dietary vitamin D fortification.6 These findings suggest that vitamin D intake and production are not the sole causes of hypercalcaemia in sarcoidosis.

Despite the conflicting evidence over the role of vitamin D intake/production in sarcoidosis-associated hypercalcaemia, several authoritative reviews have recommended avoidance of sunlight exposure and vitamin D supplements.6–8 Adopting such recommendations is likely to lead to vitamin D insufficiency, which is associated with various adverse skeletal outcomes including secondary hyperparathyroidism, increased bone turnover, low bone mineral density (BMD) and increased risk of fracture.14 There is a high prevalence of low BMD in cross-sectional studies of patients with sarcoidosis,7 13 15–18 and glucocorticoid use is common and well known to have adverse skeletal effects. Thus, it is possible that treatment recommendations of sarcoidosis may worsen skeletal health by inadvertently promoting vitamin D insufficiency.

There has been recent interest in the effects of vitamin D supplements in patients with sarcoidosis.19–22 We have conducted a randomised controlled trial to determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation on surrogate measures of skeletal health in patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D insufficiency.

Methods

Participants

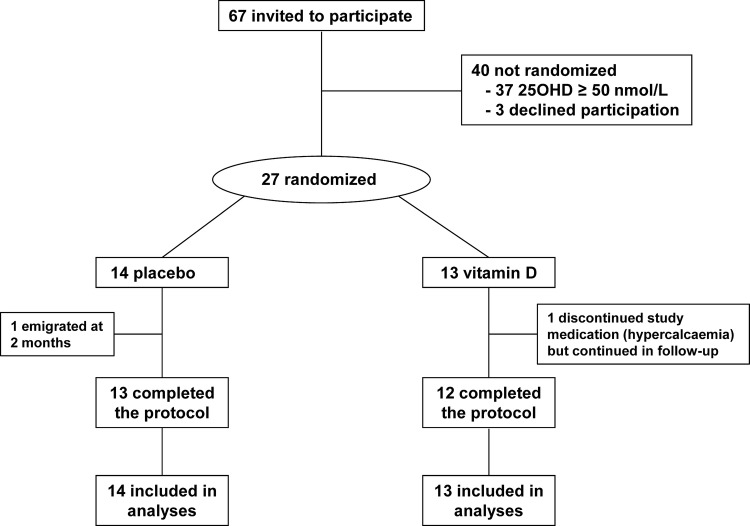

Patients with sarcoidosis attending the interstitial lung disease clinic at our hospital were invited to participate. Newspaper advertisements were also placed. Potential participants were eligible if they had sarcoidosis diagnosed by biopsy and/or typical pattern on high-resolution computed tomography and screening 25OHD <50 nmol/L, but were excluded if they had serum creatinine >150 μmol/L, nephrocalcinosis, albumin-adjusted serum calcium >2.55 mmol/L, concurrent major systemic illness or BMD T score <−2.5 at the spine or hip. Participants were recruited between September 2007 and December 2010. The flow of participants is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants.

Protocol

Participants were randomised to receive either 50 000 IU of cholecalciferol or placebo weekly for 4 weeks followed by 50 000 IU cholecalciferol or placebo every month for 11 months. Patients were asked to continue their usual diet to maintain their dietary calcium intake in accordance with locally recommended practice. Calcium supplements were not administered. Treatment allocations were randomised by the study statistician, using a variable block size schedule, based on computer-generated random numbers. Study medication was dispensed into identical bottles and labelled with participant numbers by a staff member not otherwise involved in the study. To ensure masking, only the statistician and this staff member had access to treatment allocation, and neither had contact with participants. All other study personnel and participants were blinded to treatment allocation throughout.

The primary endpoint was the change in serum calcium during 12 months with vitamin D supplementation. Secondary endpoints were the change in urine calcium, change in markers of bone turnover and change in BMD during 12 months. It was planned to recruit 40 participants, for which the study had >80% power (α=0.05) to detect a difference in serum calcium of 0.10 mmol/L between groups. Recruitment was stopped after more than 3 years when 27 participants were recruited.

Measurements

At baseline, every 2 weeks for 8 weeks, then at 12, 16, 26, 39 and 52 weeks, fasting blood and second-voided morning urine samples were collected. Samples for calcitropic hormones and bone turnover markers were stored at −70°C until they were batch-analysed. At baseline, 4, 26 and 52 weeks, 24 h urine samples were collected. The following assays were used: the screening 25OHD was measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minnesota, USA), but all 25OHD samples from the study including the baseline sample were measured by liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (ABSciex API 4000); 1,25OHD by RIA (IDS, Tyne and Wear, UK), serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (E170, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA); serum procollagen type-I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) and serum β-C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) by the Roche Elecsys 2010 platform (Roche Diagnostics). BMD was measured every 6 months at the lumbar spine, proximal femur and total body using a GE Prodigy dual-energy X-ray absorptiometer (GE Lunar, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Daily calcium intake was assessed at baseline using a validated questionnaire.23

Statistics

Baseline differences between groups for continuous variables were assessed using Student's t test, and for categorical variables using the χ2 test. All analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis. A mixed models approach to repeated measures with an unstructured covariance structure was used to examine the time course of response in the treatment and control arms for serum calcium, urine calcium, calcitropic hormones, bone turnover markers and BMD measurements by fitting main and treatment-by-time interaction effects. Post hoc comparisons between groups at individual time points were explored using the method of Tukey. BMD data were analysed using raw data, although results are presented as percentage change from baseline adjusted for baseline between-groups differences, for ease of interpretation. All tests were two-tailed and hypothesis tests were deemed significant for p<0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA, V.9.2)

Results

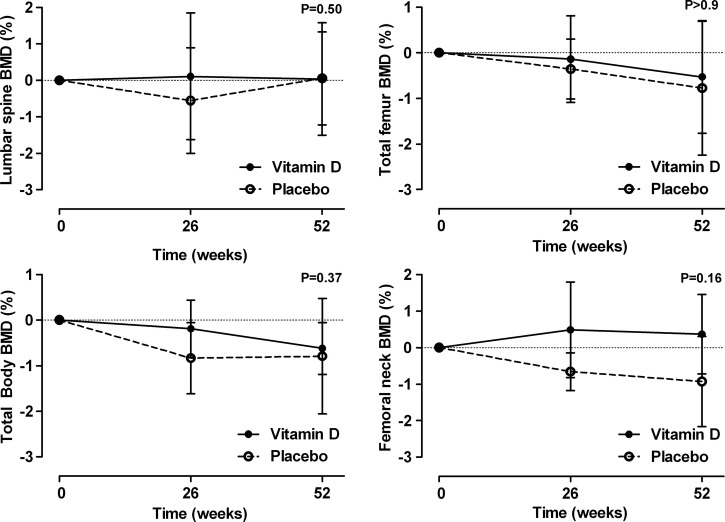

The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar (table 1). The mean (range) 25OHD at the study screening visit was 35 (14–48) nmol/L in the treatment group, and 38 (12–49) nmol/L in the controls. The baseline 25OHD measurements from the first study visit (average 3 weeks after screening 25OHD) that were stored and then measured at the end of the study using a different assay were slightly higher than the screening 25OHD in both groups (table 1). Vitamin D supplementation led to an immediate increase in 25OHD levels, and a sustained difference between the groups that persisted throughout the trial (p<0.001; figure 2). There was also an immediate increase in 1,25OHD levels in response to vitamin D supplementation, but this did not persist. While the between-groups differences over the trial were statistically significant (p=0.007), by the end of the trial 1,25OHD levels were similar in both groups (figure 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Vitamin D | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| n=13 | n=14 | |

| Age (years) | 56 (10) | 57 (9) |

| Female | 10 (77) | 9 (64) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| European | 10 (77) | 9 (64) |

| Indian | 1 (8) | 3 (21) |

| Other | 1 (8) | 2 (14) |

| Weight (kg) | 75 (19) | 72 (13) |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 730 (670) | 660 (330) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 3 (23) | 0 (0) |

| Never smoked | 8 (63) | 9 (64) |

| Glucocorticoid use | ||

| Past oral use | 7 (54) | 9 (64) |

| Current oral use | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Current inhaled use | 6 (46) | 1 (7) |

| Sarcoidosis extent | ||

| Pulmonary involvement | 11 (85) | 8 (57) |

| Extrapulmonary involvement | 6 (46) | 7 (50) |

| Chest radiograph stage at baseline | ||

| 0 | 1 (10) | 6 (46) |

| 1 | 1 (10) | 1 (8) |

| 2 | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 3 (30) | 4 (31) |

| 4 | 4 (40) | 2 (15) |

| Bone density (g/cm2) | ||

| Lumbar spine | 1.16 (0.19) | 1.13 (0.11) |

| T score | −0.2 (1.6) | −0.6 (0.9) |

| Total hip | 0.95 (0.11) | 0.93 (0.11) |

| T score | −0.6 (0.9) | −0.8 (0.9) |

| Femoral neck | 0.89 (0.13) | 0.91 (0.09) |

| T score | −1.2 (1.0) | −0.9 (0.7) |

| Total body | 1.15 (0.10) | 1.11 (0.07) |

| Adjusted serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.24 (0.06) | 2.26 (0.12) |

| Serum phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.23 (0.15) | 1.06 (0.17) |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/L) | 74 (14) | 77 (12) |

| 24 h urine calcium (mmol/day) | 4.6 (3.4) | 6.6 (5.2) |

| Screening 25-hydroxyvitamin D (nmol/L)* | 35 (12) | 38 (9) |

| Baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D (nmol/L)* | 40 (17) | 45 (17) |

| 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (pmol/L) | 109 (34) | 116 (25) |

| Parathyroid hormone (pmol/L) | 4.0 (1.6) | 4.9 (2.0) |

| P1NP (ug/L) | 37 (12) | 40 (15) |

| β-CTX (ng/L) | 310 (130) | 360 (210) |

*25-Hydroxyvitamin D were measured at the screening study visit using a Diasorin assay, while the baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D at the first study visit (average 3 weeks later) were stored frozen until the end of the study and then measured with a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay (see text). Data are mean (SD) or n (%).

P1NP, serum procollagen type-I N-terminal propeptide; β-CTX, serum β-C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen.

Figure 2.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation on 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels. Data are mean and 95% CI. p Values are for time-by-treatment interaction. Asterisks indicate significant between-groups differences at individual points.

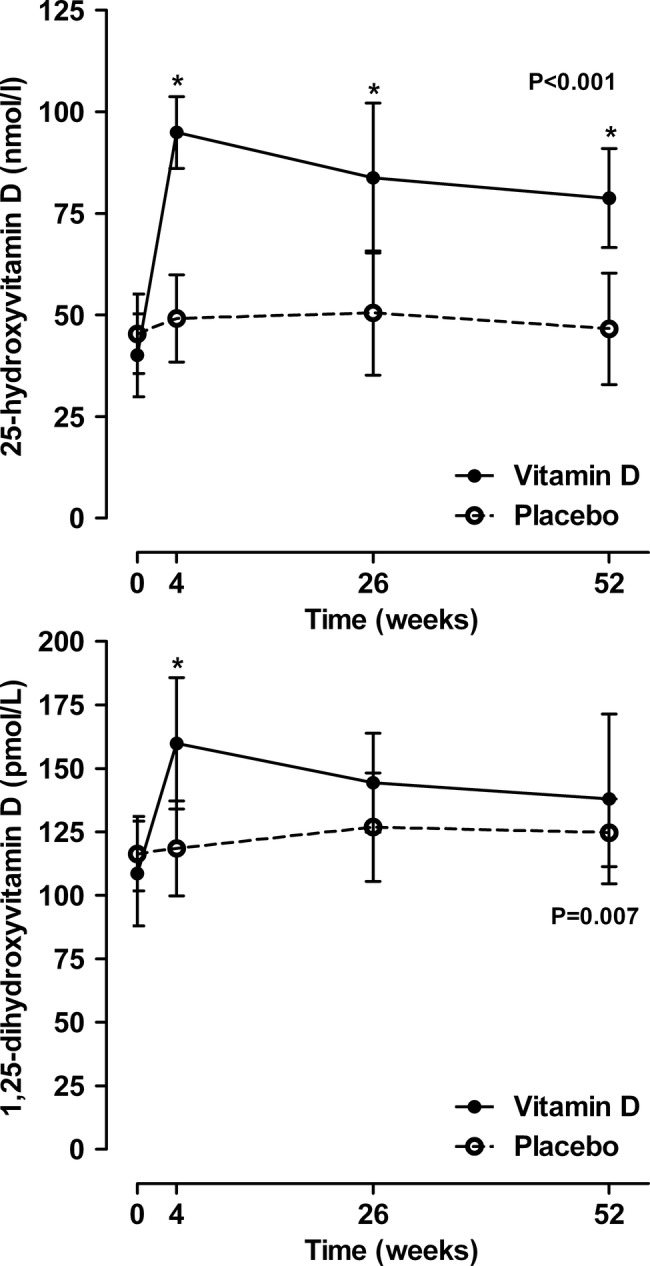

Figure 3 shows that vitamin D supplements had no effect on either average albumin-adjusted serum calcium (p=0.46) or 24 h urine calcium levels (p=0.10) throughout the trial. There were no between-group differences at any time point in participants with 24 h urine calcium >10 mmol/day (baseline vitamin D vs control 1 vs 4; 4 weeks 4 vs 4; 16 weeks 1 vs 2; 52 weeks 3 vs 2). One participant in the vitamin D group and none in the control group had sustained hypercalcuria with 24 h urine calcium >10 mmol/day in all the three visits during follow-up. One participant developed hypercalcaemia during the trial—a 51-year-old woman diagnosed with sarcoidosis 2 years prior to study entry, with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, liver and lung involvement. She was taking inhaled glucocorticoids at study entry but no other medication. She was assigned to vitamin D treatment and table 2 shows that hypercalcaemia was recognised at 6 weeks, by which time she had taken five 50 000 IU doses of cholecalciferol. She was vitamin D deficient at baseline, and treatment increased her 25OHD level to 69 nmol/L. There was a marked increase in 1,25OHD, 24 h urine calcium, serum phosphate and creatinine levels and suppression of the PTH levels following vitamin D supplementation, but she remained asymptomatic throughout. No further study medication was taken and the biochemical abnormalities resolved without specific treatment by week 16 of the trial. When this participant was excluded from the analyses for serum calcium and 24 h urine calcium, the results did not change substantially except that there was no visible rise in the average albumin-adjusted serum calcium at 6 and 8 weeks in the vitamin D group (data not shown).

Figure 3.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation on albumin-adjusted serum calcium and 24 h urine calcium levels. Data are mean and 95% CI. p Values are for time-by-treatment interaction.

Table 2.

Time course of hypercalcaemia in patient randomised to vitamin D supplements

| Weeks* | Dietary calcium (mg/day) | Serum calcium† (mmol/L) | Serum phosphate (mmol/L) | Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 24 h Urine calcium (mmol/day) | 25OHD (nmol/L) | 1,25OHD (pmol/L) | PTH (pmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 460 | 2.26 | 1.24 | 76 | 4.2 | 18 | 77 | 2.3 |

| 2 | 2.36 | 1.28 | 74 | |||||

| 4 | 2.48 | 1.57 | 83 | 14.4 | 69 | 218 | 0.9 | |

| 6 | 2.88 | 1.55 | 112 | |||||

| 7 | 2.87 | 1.31 | 125 | |||||

| 8 | 2.65 | 1.45 | 124 | |||||

| 12 | 2.46 | 1.23 | 93 | |||||

| 16 | 2.22 | 1.14 | 75 | |||||

| 26 | 2.28 | 1.04 | 71 | 31 | 81 | 2.2 | ||

| 52 | 2.27 | 1.11 | 78 | 6.7 | 41 | 77 | 2.1 |

*Study treatment was stopped at 6 weeks when hypercalcaemia was recognised. The last dose was taken at week 5, and five 50 000 IU doses of cholecalciferol were taken over 5 weeks.

†Albumin-adjusted serum calcium.

1,25OHD, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; 25OHD, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

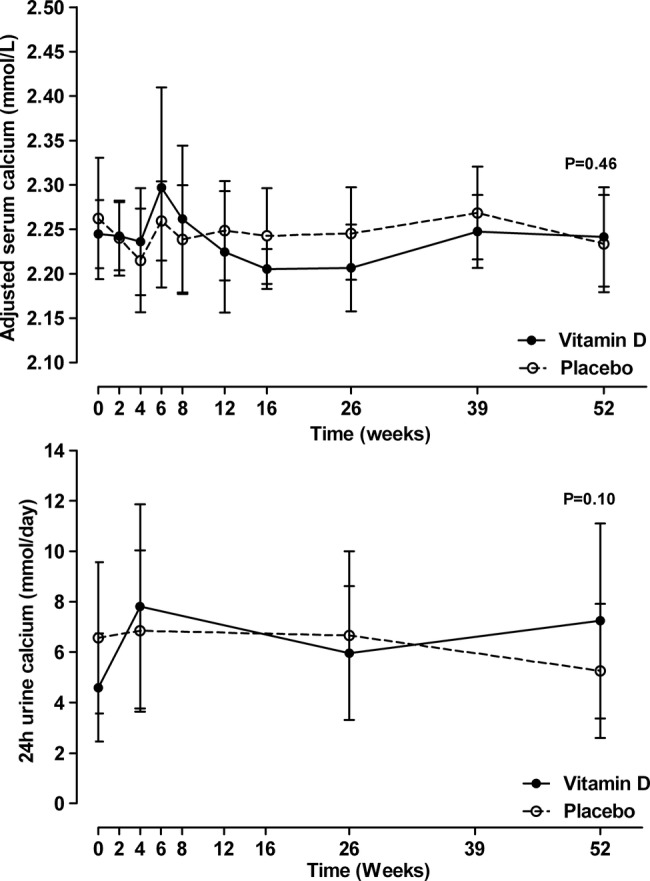

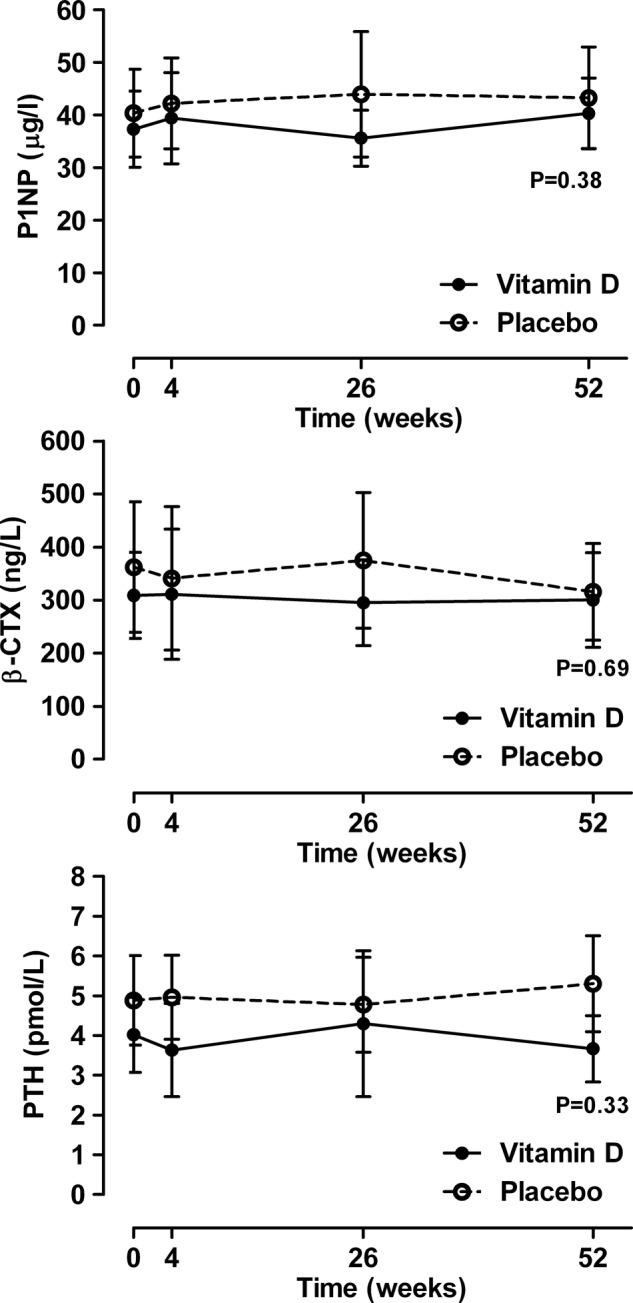

The effect of vitamin D supplements on bone turnover markers and PTH are shown in figure 4 and on BMD in figure 5. Vitamin D supplementation had no effect on any of these variables (p>0.16 for all variables).

Figure 4.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone turnover markers and serum parathyroid hormone. Data are mean and 95% CI. p Values are for time-by-treatment interaction. P1NP, Procollagen type-I N-terminal propeptide; β-CTx, β-C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen.

Figure 5.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density (BMD). Data are mean and 95% CI for the percentage change from baseline adjusted for baseline BMD. p Values are for time-by-treatment interaction.

Other than the one participant treated with vitamin D who developed hypercalcaemia (proportion 8%, 95% CI 1% to 33%), there were no other adverse events potentially related to treatment during the trial. One participant (randomised to vitamin D) required prolonged treatment with oral glucocorticoids, and one participant (randomised to placebo) received a single infusion of zoledronic acid at 11 months because of an underlying neurological disorder that had led to an increased risk of falls and fracture.

Discussion

Vitamin D supplementation of patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D insufficiency did not alter average serum calcium or urine calcium levels, and also did not affect BMD or markers of bone turnover but caused one case of significant hypercalcaemia. 25OHD levels were in a range many experts consider suboptimal at baseline (average <50 nmol/L) and vitamin D supplementation led to average 25OHD levels of >75 nmol/L throughout the trial, levels generally considered to indicate adequate vitamin D status. Thus, our findings of an absence of benefit from vitamin D supplements, together with infrequent but significant hypercalcaemia, suggest that there is little indication for vitamin D supplements in patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D insufficiency.

Recent research has linked low 25OHD levels with numerous adverse non-skeletal outcomes.24 This information, when added to the existing data linking low 25OHD levels with adverse skeletal outcomes,14 has led to renewed interest in the role of vitamin D in health. In clinical practice, there has been a large increase in measurement of 25OHD25 26 and calls for widespread vitamin D supplementation.27 However, these associations between low vitamin D status and adverse health outcomes have been generated from observational studies which cannot determine causality. There are now a growing number of randomised controlled trials that have not shown benefits from vitamin D supplements on a wide range of endpoints. Thus, meta-analyses of such trials have shown no benefit of vitamin D supplementation (when used without coadministered calcium supplements) on falls,28 fractures,29 mortality,30 cardiovascular events30 and cancer.31 In our study, which was powered to assess serum calcium rather than BMD effects, we did not find evidence for benefit of vitamin D supplements on surrogate markers of skeletal health in a group of patients with sarcoidosis who had mildly low 25OHD levels, consistent with these findings.

The mechanism of hypercalcaemia in sarcoidosis is well described. Extrarenal production of 1,25OHD in activated macrophages in granulomata leads to increased intestinal calcium absorption and increased bone resorption which collectively produce hypercalcaemia.3 It is unclear whether circulating 25OHD levels are implicated in causing hypercalcaemia, with some evidence supporting4–10 and some not supporting1 6 11–13 each viewpoint, as discussed earlier. Our study tends to support the former view for two reasons: first, one patient developed significant hypercalcaemia within a short time of starting vitamin D supplements, and there was prompt resolution of the hypercalcaemia without other treatment after the supplements were stopped. Second, in the entire cohort there was a rapid increase in 1,25OHD with vitamin D supplements, although the increase did not persist. Both pieces of data suggest that abrupt changes in 25OHD can increase 1,25OHD, and in a minority of patients this can cause hypercalcaemia. The characteristics that predispose to the development of hypercalcaemia remain unclear. It is possible that increasing 25OHD more slowly using small, incrementally increasing doses of vitamin D, may avoid this complication, but this would need to be tested in closely monitored clinical trials.

Our study has several limitations. It is a small study and therefore may be at risk of type II error. We carried out simulations to explore what effect sizes could have been statistically significant in this study. We simulated an increased effect size in the treatment group (without varying data in the placebo group or the sample size) in the models used in the study analyses. A difference between the groups at 1 year of 0.06 mmol/L in serum calcium, the primary endpoint, would have reached conventional statistical significance. This is 60% of the value used in the study power calculation (0.1 mmol/L) that we considered to be clinically relevant when designing the study. Similarly, the corresponding between-groups differences that would have reached statistical significance for the other main endpoints were: 2.4 pmol/L for PTH, 7 µg/L for P1NP, 140 ng/L for CTX and 0.5%–1.9% for BMD, depending on site. Differences below these amounts would be of questionable clinical relevance. Thus, while small, the study did have more than adequate power to detect clinically relevant differences. A second limitation is regarding the screening vitamin D measurement. All participants had 25OHD <50 nmol/L at the screening visit measured using a Diasorin RIA. All study samples for 25OHD were frozen and then assayed in a single batch at another laboratory using an LC-MS/MS assay. The 25OHD levels measured using LC-MS/MS were on average slightly higher than those measured using the Diasorin immunoassay, and 9/27 participants had 25OHD >50 nmol/L at the baseline visit. Variation between results from different 25OHD assays is well described, and while LC-MS/MS is usually considered the gold standard, immunoassays and LC-MS/MS have limitations.32 Few participants had 25OHD <25 nmol/L at baseline, thus our results may not apply to individuals with very low 25OHD levels.

In summary, we did not find evidence of benefits on surrogate markers of skeletal health from vitamin D supplementation in patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D insufficiency. However, there was evidence of harm with one case of significant hypercalcaemia. The absence of benefit together with the risk of infrequent but significant adverse effects suggests that there is little indication for vitamin D supplements in patients with sarcoidosis and vitamin D levels in the range in this study (12–49 nmol/L).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MB, AG, AH, IR and MW designed the study. SF and AH ran the study. MB and GG conducted the statistical analyses. MB drafted the article. All the authors critically reviewed the draft manuscript and approved the final version. MB is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the Greenlane Research and Education Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study received ethical approval from the Northern X regional ethics committee and the trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12607000364471.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. A worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1976;278:321–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1885–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer FR, Adams JS. Abnormal calcium homeostasis in sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1986;315:755–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell NH, Gill JR, Jr, Bartter FC. On the abnormal calcium absorption in sarcoidosis. Evidence for increased sensitivity to vitamin D. Am J Med 1964;36:500–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandler LM, Winearls CG, Fraher LJ, et al. Studies of the hypercalcaemia of sarcoidosis: effect of steroids and exogenous vitamin D3 on the circulating concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3. Q J Med 1984;53:165–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma OP. Vitamin D, calcium and sarcoidosis. Chest 1996;109:535–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzato G. Clinical impact of bone and calcium metabolism changes in sarcoidosis. Thorax 1998;53:425–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conron M, Young C, Beynon HL. Calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis and its clinical implications. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:707–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnema SJ, Moller J, Marving J, et al. Sarcoidosis causes abnormal seasonal variation in 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol. J Intern Med 1996;239:393–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor RL, Lynch HJ, Jr, Wysor WG., Jr Seasonal influence of sunlight on the hypercalcemia of sarcoidosis. Am J Med 1963;34:221–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberts C, van den Berg H. Calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis. A follow-up study with respect to parathyroid hormone and vitamin D metabolites. Eur J Respir Dis 1986;68:186–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson LG, Liljestrand A, Wahlund H. Treatment of sarcoidosis with calciferol. Acta Med Scand 1952;143:281–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler RA, Funkhouser HL, Petkov VI, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in patients with sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci 2003;325:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lips P. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 2001;22:477–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montemurro L, Fraioli P, Rizzato G. Bone loss in untreated longstanding sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis 1991;8:29–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rottoli P, Gonnelli S, Silitro S, et al. Alterations in calcium metabolism and bone mineral density in relation to the activity of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis 1993;10:161–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamada K, Nagai S, Tsutsumi T, et al. Bone mineral density and vitamin D in patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999;16:219–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sipahi S, Tuzun S, Ozaras R, et al. Bone mineral density in women with sarcoidosis. J Bone Miner Metab 2004;22:48–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke RR, Rybicki BA, Rao DS. Calcium and vitamin D in sarcoidosis: how to assess and manage. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010;31:474–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma OP. Vitamin D and sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16:487–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sage RJ, Rao DS, Burke RR, et al. Preventing vitamin D toxicity in patients with sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:795–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweiss NJ, Lower EE, Korsten P, et al. Bone health issues in sarcoidosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:265–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angus RM, Sambrook PN, Pocock NA, et al. A simple method for assessing calcium intake in Caucasian women. J Am Diet Assoc 1989;89:209–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007;357: 266–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sattar N, Welsh P, Panarelli M, et al. Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: costly, confusing, and without credibility. Lancet 2012;379:95–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Davidson JS, et al. Should measurement of vitamin D and treatment of vitamin D insufficiency be routine in New Zealand?. N Z Med J 2012;125:83–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearce SH, Cheetham TD. Diagnosis and management of vitamin D deficiency. BMJ 2010;340:b5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murad MH, Elamin KB, Abu Elnour NO, et al. Clinical review: the effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2997–3006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avenell A, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD, et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elamin MB, Abu Elnour NO, Elamin KB, et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1931–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, et al. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:827–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter GD. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D assays: the quest for accuracy. Clin Chem 2009;55:1300–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.