Abstract

Visualising the molecular strands making up the glycocalyx in the lumen of small blood vessels has proved to be difficult using conventional transmission electron microscopy techniques. Images obtained from tissue stained in a variety of ways have revealed a regularity in the organisation of the proteoglycan components of the glycocalyx layer (fundamental spacing about 20 nm), but require a large sample number. Attempts to visualise the glycocalyx face-on (i.e. in a direction perpendicular to the endothelial cell layer in the lumen and directly applicable for permeability modelling) has had limited success (e.g. freeze fracture). A new approach is therefore needed. Here we demonstrate the effectiveness of using the relatively novel electron microscopy technique of 3D electron tomography on two differently stained preparations to reveal details of the architecture of the glycocalyx just above the endothelial cell layer. One preparation uses the novel staining technique using Lanthanum Dysprosium Glycosamino Glycan adhesion (the LaDy GAGa method).

Keywords: Transmission electron microscopy, permeability, filtration

Introduction

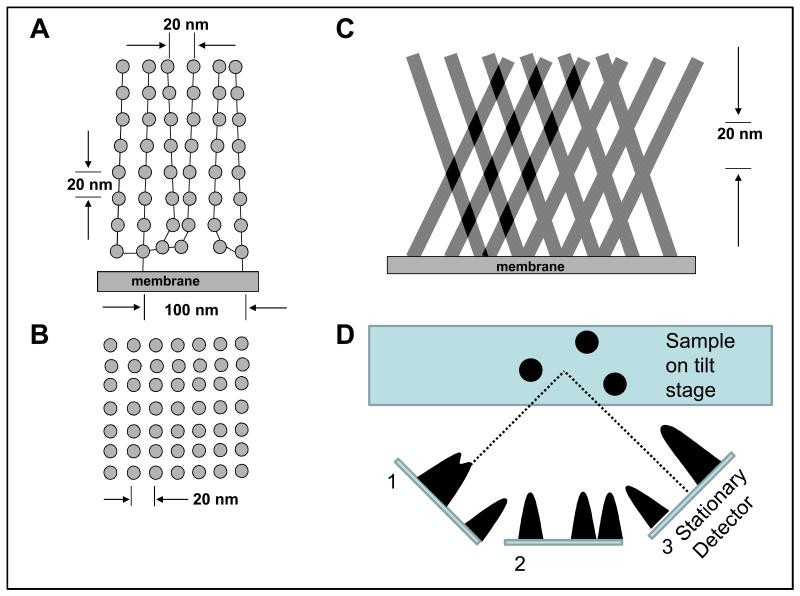

The endothelial glycocalyx is a layer, or surface coat, on the luminal side of blood vessels that is thought to have many functions including molecular filtering. It consists of proteoglycan molecules (Figure 1(A,B)) which are thought to be organised in a near-tetragonal array of spacing about 20 nm in molecular clusters (tufts). There is also a larger spacing between clusters which is in the 100 nm region and has been thought to correlate with a cytoskeletal layer below the endothelial cell membrane. These spacings have been deduced from careful image processing and analysis of numerous transmission electron micrographs (TEM) recorded over many years using a variety of staining methods on a variety of tissues (1, 23). Several authors (e.g. (29, 31)) have taken preliminary data from the study of frog microvessels (23) to use in mathematical models of filtration, providing mathematical support for the concept that it is the glycoprotein tufts that define the plasma filtering behaviour at the endothelial cell surface layer. However, in order to define the glycocalyx structure in more detail to enable development of more reliable models it is necessary to be able to visualise the layer in three-dimensions at molecular resolution. An extensive series of attempts to do this by freeze-fracture, deep-etch electron microscopy (23) was only partially successful, but it did show one of the very few available images of the glycocalyx viewed ‘en face’ (luminal view). A much better and more reliable method is needed to make this routine.

Figure 1.

Previous interpretation of the glycocalyx staining patterns from the side (A) and plan view from the lumen (B). This demonstates a 20nm tetragonal lattice with membrane binding at 100nm intervals (23). (C) An example of possible misinterpretation of the appearances of projected sections, where successive tilted layers of ‘smooth’ fibres could cross through the depth of the section to give apparent 2D periodicities (Moiré patterns). (D) Explanation of electron tomography. The electron beam passes through the sample. The sample is tilted so that images are taken at different angles (1, 2, 3) without moving the detector. The images at known viewing angles can then be reconstructed, for example using back-projection, to produce a 3D image of the sample (see Supplementary Material for movie).

To be able to comprehend the ultrafiltration properties of the glycocalyx in detail there are three main parameters which need to be obtained: the diameter of the glycoprotein ‘fibres’; the centre-to-centre fibre spacing; and any 3D ordering of the fibres (e.g. in a regular lattice structure). There are further parameters which might be explored (e.g. fixed charge density and distribution), but these are not within the scope of this present paper. Here we describe new results obtained using the relatively novel technique of 3D electron tomography applied to the glycocalyx. Electron tomography results in 3-dimensional electron density maps that can be viewed in any direction and from which areas of interest can be selected and analysed. This technique applied to the glycocalyx has the potential to reveal most of the static structural details necessary to generate realistic models of filtration.

It is difficult to view the luminal aspect of the glycocalyx in conventional TEM sections, and when it is seen, it is almost impossible to know the angle of the section to the membrane and the depth within the glycocalyx of any views found. Using only the TEM side-on view (i.e. a view of the glycocalyx viewed in a direction parallel to the endothelial membrane) makes robust interpretation of any quasi-lattice difficult due to the view being a projection through several fibres of glycocalyx within a typical 50-80nm section. It would be more convincing to be able to see this lattice directly in a ‘face on’ (luminal) view and not as a projection of several fibres from the side.

In addition, in studying side-on views, the possibility exists that resulting 2D lattices in the fibre array, including an apparent regularity along the fibres themselves (i.e. in a direction perpendicular to the membrane – referred to here as ‘vertical’ spacings), could be an artefact similar to what is known as a Moiré pattern. This possibility is illustrated in Figure 1(C), where it can be seen that the effect of two or more ‘combs’ of smooth fibres with different tilts and overlapping in projection through a section could give rise to apparent ‘vertical’ spacings even though the fibres themselves are smooth. If fibre arrays happen to cross behind each other like this in a projected view, what appears as a 2D lattice could result. In order to eliminate this possibility it is necessary to visualise the glycocalyx in three dimensions so that individual thin fibre layers can be studied.

Electron Tomography is a technique which overcomes these problems, and has used to image bacterial flagellae, which are modified glycocalyx (15). The methodology is to record a series of electron micrographs of a section tilted at various known angles to the electron beam (Figure 1(D)) and then to recombine this digital information to give a three–dimensional (xyz) staining density map of what is in the section. The advantage of tomography in general is that the output reveals the varying density through the depth of the section and, if the section is moderately thick (circa 300 nm), a good 3D view of the glycocalyx and its surrounding material can be obtained. By convention the viewing direction (the section depth) is the z axis and the plane of the section is defined by x and y.

To generate a perfect reconstruction it is necessary to view the section from all possible directions at angular separations defined by the resolution required in the reconstruction. It is not possible, however, to view the sections directly from the side (i.e. at 90°; edge on) in transmission electron microscopy. The practical limit to the possible section tilt is an angle of around 65° and there is missing information due to the missing viewing angles between 65° and 90°. This manifests itself particularly in the z direction of the reconstruction. To partially alleviate this universal problem with tomography a second tilt series with the tilt axis perpendicular to the first can be carried out. The resulting reconstruction of the section has approximately half the resolution in the z direction compared with x and y. A larger range of tilt angles is more important in improving resolution than the acquisition of more micrographs at more closely spaced angles within a given angular range (2).

It is relatively straightforward to find regions of glycocalyx in transmission electron micrographs with the section at a non-specific angle in relation to the membrane. Electron tomography can then be used to give a 3D reconstruction of the staining intensity in the section within which the glycocalyx can be found. Once found the glycocalyx layer can be rotated to present any required view to the observer, particularly edge on and luminal views.

Two different glycocalyx fixation and staining methods have been applied here. Normal perfusion fixation while applying the fixative to the tissue structures in a very rapid fashion deprives the tissues of oxygen by removing the blood. In addition, with glutaraldehyde, oxygen is consumed in the fixation reactions. In the first method used here, that of Rostgaard et al (1993)(20), this problem was addressed by perfusing the microvessels with an oxygen-saturated fluorocarbon in suspension in the phosphate buffered glutaraldehyde fixative solution. The novel second technique (the LaDy GaGa technique) ignores the oxygen tension and relies upon the rapid diffusive movements of trivalent lanthanide ions to fix and stain the glycocalyx prior to any glutaradehyde fixation and its attendant loss of oxygen tension that might interfere with the ‘in vivo’ structure of the glycocalyx. Lanthanides have been used previously on their own, for example, terbium (28), or lanthanum (8), and lanthanum has also been used in combination with Alcian Blue (25). The density of the lanthanoids increases disproportionately with higher molecular weight because of the effect of electron shielding. Lanthanum (mw 139) has a 3+ ion radius of 120 pm whereas dysprosium (mw 162.5) has a 3+ ion radius of only 90 pm; in other words dysprosium has a higher charge density on a similarly charged ion and it has similar chemistry to lanthanum. The smaller dysprosium ions should penetrate into smaller spaces compared with lanthanum, but will still react with the glycocalyx in a similar manner.

The tomography technique reported here shows a dramatic improvement of detail over previous approaches and results from the Rostgaard and LaDy GaGa methods are similar and consistent.

Methods

Sample preparation

Two specimens obtained using two different fixing and staining methodologies for the glycocalyx were used here to demonstrate the electron tomography technique. The first specimen was an archived block used by Rostgaard et al in previous publications (1, 16, 18-20). Briefly, the preparation method was as follows. Following induction of surgical anaesthesia of Wistar rats, the trachea was cannulated to facilitate adequate artificial ventilation. A self-retaining cannula was inserted into the left ventricle of the heart and clamped tightly. The cannula consisted of two barrels. The outer barrel was connected to a peristaltic pump which delivered the fixative (2% glutaraldehyde and 13.3% oxygenated fluorocarbon in 0.05M sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4). The inner barrel was connected to a pressure transducer that monitored the perfusion pressure, directing the pump to deliver the perfusate at a steady pressure of 100 mm Hg. The vena cava was severed immediately before the perfusion was initiated. After fixation, small specimen blocks (1 mm3) were trimmed, rinsed in 0.12 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h, postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h, very briefly rinsed (10-20 sec) in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), rinsed in distilled water and treated with 1% tannic acid in distilled water for 3 h. The samples were stained en bloc in 1% uranyl acetate in distilled water overnight, rinsed in distilled water and dehydrated in 70%, 96% and 100% ethanol. The specimens were transferred to propylene oxide and embedded in Epon according to standard procedures.

The second method involved the intracardiac perfusion of a glutaraldehyde fixative containing lanthanum and dysprosium to stain the glycosaminoglycans (Lanthanum Dysprosium GlycosAminoGlycan adhesion method (LaDy GAGa)). A rat was injected with a lethal dose of 0.7 ml/kg sodium pentobarbitone (Lethobarb, Ayrton Saunders Ltd UK), the thorax was promptly opened and the left side of the heart was perfused at 100 mmHg pressure with a flush solution of HEPES buffered mammalian Ringer containing 0.5% LaNO3.6H2O, 0.5% DyCl3.6H2O, (room temperature, pH 7.3). Heparin was not used as an anticoagulant as this was found to react with the lanthanides in solution. Flushing with a 3 ml bolus was followed by 100 ml of 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% sucrose in the same solution as above (room temperature, pH 7.3). Tissues started to stiffen within 30 seconds. Samples 1 mm in diameter were isolated from the psoas muscle and were washed with HEPES buffer and transferred to 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 1 h, rinsed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), rinsed in distilled water, en bloc stained in 1% uranyl acetate in distilled water overnight (4C), rinsed in distilled water and dehydrated in 70%, 90% and 100% ethanol. The specimens were transferred to propylene oxide and infiltrated and embedded in Araldite resin.

80 nm thick survey sections used to locate vessels of interest and serial 300 nm thick sections for tomography were cut with a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E microtome and mounted on Pioloform coated slot grids. Gold beads of 10 nm or 15 nm diameter (fiducial markers: Aurion, Wageningen, Netherlands) were carefully added to both sides without dilution. The gold bead suspensions were first sonicated to reduce coagulation, then a 35 gauge needle on a 1 ml syringe was sufficient to add a drop of this fiducial suspension to each side of the section. The section was turned after 10 min, and after a further 10 min a filter paper was touched to the side of the slot grid to remove excess liquid.

Electron tomography was performed on 300 nm sections with an FEI T20 200 kV electron microscope with a dual tilt holder. Micrographs were recorded with the section tilted in increments of 1° with a minimum range between −60° and +60° with an Eagle 4096 × 4096 CCD camera (FEI) at 29,000x magnification (0.37nm/pixel). The exposure time was 2.0 s for the 0° view and was increased for each degree up to 3.2s for ±60° views to account for the increase of section thickness for higher viewing angles. Micrographs, recorded automatically but with human intervention where necessary, were stored in a 16 bit MRC file stack. The process was repeated for the same section location with a second tilt axis at 90° (in the x-y plane) to the first. The different tilted views were reconstructed into a single 3D density image stack using IMOD tomogram reconstruction software (9, 12). It was noted that a careful auto-focus set-up and a steady beam intensity, though not imperative, significantly improved the ease of reconstruction.

Using Fiji image analysis software (17, 21), the reconstructions were extended by a factor of 1.54 in the z direction to account for section shrinkage estimated to be 35% (10). They were then rotated to show the glycocalyx in luminal view and areas were selected where the membrane was as flat as possible. Image volumes were selected where there was good glycocalyx coverage over a large area and a relatively flat membrane at the base. A taper was added to the area surrounding selected projection images to reduce edge effects, and a 2D Fast Fourier Transform was performed. This was followed by calculation of the autocorrelation function (AC; as previously described (1, 23)) to present a 2D map in real space of correlation distances. For example from a coordinate of high intensity in the AC the direction and distance from the centre demonstrates the presence of a common spacing in that direction in the original image.

Results

The most useful tomographic reconstructions were obtained using a relatively high electron dose and a 2 s exposure time so that the gold fiducials used for image tracking could be seen and followed even when over a densely stained sample. Since the sections had no post staining (i.e. no separate staining of the individual sections), and they were 3 to 5 times as thick as an 80 nm thick section for conventional transmission electron microscopy, areas of interest on the sample were difficult to find. A serial thin section cut at 80 nm and used as a map lowered the risk of sample damage before the area of interest was studied, and aided identification of areas suitable for imaging.

A tomogram using the Rostgaard staining technique on a rat peritubular capillary is shown in Figure 2. Figure 2(A) demonstrates the clarity of the glycocalyx from the more common TEM view; the membrane in this view is approximately 25° from parallel to the viewing direction. Supplementary Figure S1 shows a movie of the rotating image. Figure 2(B) shows the reconstruction from Figure 2(A) rotated to the ‘face on’ luminal view. An autocorrelation (AC) of the outlined area is shown in Figure 2(C). There is very obvious 2D structure in this and distances in the AC are at the same scale as distances in the original. Therefore areas of higher correlation (density) can be measured which relate directly to the spacings within the glycocalyx (Figure 2(D)). In this example the spacings are 19 nm and 24nm depending on the direction, though the planes are not exactly perpendicular, but are at 70° to each other. These distances are very similar to centre-to-centre fibre spacings found in previous work (1, 23).

Figure 2.

Analysis of a tomographic reconstruction of the glycocalyx obtained using the Rostgaard staining technique in a rat peritubular capillary. (A) is the output from the reconstruction (Scale Bar = 100 nm). (B) is the view from the lumen to the area of the black line in (A). The tomogram has been stretched to the appropriate dimensions to account for shrinkage (Scale Bar = 100 nm). (C) is the autocorrelation of the boxed area in (B) and (D) is the same autocorrelation, but with the dashed lines representing common spacing distances overlaid. (Scale bars in (C) and (D) are 50 nm ).

Figure 3(A) shows a single thin ‘vertical’ slice (1.2 nm thick after correction for shrinkage) through the glycocalyx in a choroid capillary tomogram stained by the Rostgaard method together with an autocorrelation (B) from a selected area in (A). In (C), which shows averaged results from autocorrelations of the three different areas boxed in (A), it is evident that there are periodicities both parallel to and perpendicular to the cell membrane. The slice in (A) is thin enough to include only one layer of fibres, and even so there is still regularity with ‘vertical’ spacings of about 17 and 27 nm.

Figure 3.

Figure showing that the vertical spacing observed within the glycocalyx is not a Moiré artefact. (A) shows a thin slice (about 1 nm thick; a single fibre layer) of glycocalyx from the Rostgaard staining technique (20) tomogram, from dwarf rabbit choroid capillary, with three areas selected and boxed. (B) is an autocorrelation from the right hand area in (A). (C) shows periodicities in the average autocorrelation functions from all three areas in (A) both parallel to and perpendicular to the endothelial cell membrane. There are clear ‘vertical’ perpendicular spacings apparent in the autocorrelation even though the slice is only one fibre thick. (Scale bar is 100 nm.)

A tomogram from a psoas muscle capillary stained by the LaDy GAGa method is demonstrated in Figure 4. The LaDy GAGa technique, in the examples studied here, tended to reveal greater glycocalyx coverage than the Rostgaard technique. In this tomogram the depth of glycocalyx is 75-100nm. It should be noted that in standard TEM micrographs we have noted a range from 50nm up to 400nm with variation around the same vessel. The staining was intense (Figure 4(A)) compared to the surrounding cellular tissue, so time was saved in finding well-covered glycocalyx areas. However, the dense staining made it difficult to visualise any substructure by eye. A tomographic ‘face on’ view is shown in Figure 4(B). Autocorrelation (Figure 4(C)) once again demonstrated regular spacings, in this example at 18 nm and 25 nm (Figure 4(D)) and in this case almost exactly perpendicular to each other.

Figure 4.

Analysis of a tomographic reconstruction of the glycocalyx obtained using the LaDy GAGa staining technique on mouse psoas capillary. (A) is the output from the reconstruction (Scale Bar = 100 nm). (B) is the view from the lumen in (A). The tomogram has been stretched to the appropriate dimensions to account for shrinkage (Scale Bar = 50 nm). (C,D) is the autocorrelation of the boxed area with dashed lines highlighting the lattices present in the autocorrelationin (D). (Scale Bar =50nm).

Fibre diameter is a difficult parameter to judge with the AC method. Taking the mean of the Full Width Half Maxima (FWHM) of the fitted peaks in the autocorrelation function of each slice taken parallel to the z axis can give a limited estimate (1). Mean fibre width estimated in this way for the Rostgaard method in Figure 2 was 11.7 (±0.5 SEM, 1 tomogram using all 340 fitted peaks) nm and for the LaDy GAGa staining in Figure 4 was 10.2 (±0.3 SEM, 1 tomogram using all fitted 680 peaks) nm.

Figure 5 shows the wealth of detail contained is in the tomographic reconstructions (see also Supplementary Material). This shows a stereo view of the glycocalyx in Figure 2 seen at a slight angle to the membrane (at the bottom) and in which various ‘vertical’ tufts of density can be seen, like a 3D close-up of a lawn or a tufted carpet. For the first time, the shapes of individual glycocalyx fibres are being revealed.

Figure 5.

Stereo pair of the 3D density from a section of the glycocalyx from rat peritubular capillary using the Rostgaard technique. The reconstruction has had the background subtracted, has been converted to a mesh and is shown at two slightly different viewing angles. The shapes of individual fibres are starting to be revealed. (Scale bar = 100nm).

Discussion

Successful glycocalyx tomographic reconstructions mean that for the first time we can not only view the section from the physiologically interesting luminal view, but we can also study the glycocalyx through the depth of the sample from this luminal or any other view. There are other advantages of this method as well; any glycocalyx arrangement can be observed directly in 3D rather than being inferred from analysis of a multitude of side views. This in turn means that larger areas of glycocalyx can be studied at the same time. Any directionality in the fibre array can also be considered. Since the angle of the membrane can be determined directly, it is possible to assess any vertical differences in the arrangement of the fibres as they progress away from the membrane. Perhaps most importantly tomography enables measurements of fibre matrix spacing to be made accurately without the three dimensional interference problems seen in earlier studies (1, 23).

Another key parameter to determine is the diameter of the fibres. This was estimated by Squire et al. (2001) to be about 10 to 12 nm(23). However, in the later work by Arkill et al. (2011) the estimated fibre diameter was much larger (18.8±2)(1). It is well known that staining methods can cause artefacts and tannic acid, for example, is known to increase the measured sizes of stained particles (5, 7). Arkill et al. (2011) assumed that this must be the case with their analysis using material obtained with the Rostgaard technique involving tannic acid. However, it is of significance that results from our new tomograms using two completely different staining methods have resulted in estimates of fibre diameter that are very similar, 11.7 (±0.5 SEM) nm and 10.2 (±0.3 SEM) nm, and in agreement with previous studies using mathematical analysis of the stained glycocalyx on single sections (23). This suggests that tannic acid itself was not causing the over-estimate of diameter. One possibility is that using electron tomography, the slices that were analysed were only a single fibre layer thick, whereas in standard TEM the sections contain several overlapping fibre layers. It may be because of the effects of overlapping fibres through the depth of the section that the FWHM method in the work of Arkill et al. (2011) overestimated the fibre thickness(1). Even so, because of the large standard deviation in our measurements here, an independent method of estimating fibre diameter should be employed in the future, for example atomic force microscopy(14).

One issue highlighted by tomography is the shrinkage of the sample, and may explain the fibre plans in figure 2 not being perpendicular. Luther and Crowther (10) found that samples shrank by a proportion of approximately 0.95 in x and y and by 0.65 in z. In this study it was observed (for example by the distortion of spherical caveolae) that similar distortions occur in our samples, and was corrected for using the bubbles as indicators of shrinkage. A matter for future work is to determine this with more precision as shrinkage does appear to vary to some extent with the stain and the tissue involved. In future a low dose protocol could be used to determine section specific shrinkage and also anisotropic shrinkage before the actual data tomogram is taken(11). The space between the fibres is the important physiological distance for permeability. A 5% lateral shrinkage (i.e. in x and y) would equate to approximately 0.5 nm alteration in the glycocalyx spacing; determination of accurate spacings requires accurate knowledge of section shrinkage. Another possible option would be to use cryo-tomography with possibly less shrinkage but this would not be the mode of choice here due to the difficulty in finding the location of interest.

Estimates of the thickness (or depth) of the glycocalyx in our studies range from less than 50 nm to 100nm using the Rostgaard technique and 50nm to 400nm using the LaDy GAGa technique. This contrasts with values of 400-600nm inferred from the exclusion of fluorescent macromolecules from the luminal surface of microvessels in vivo (e.g. (26-27)) and micro-particle image velocimetry studies on living microvessels (e.g. (22)). Weinbaum et al (2007) (29) suggested that an outer less dense layer of the glycocalyx might be lost during preparation of tissues for electron microscopy and details of an inner layer only are seen in electron micrographs. This could indeed be the case but as recognised by Weinbaum et al (2007) (29)and emphasised in a recent review by Curry &Adamson (2011)(3), it raises a conundrum. Using the data of Squire et al (2001) (23)for fibre spacing and fibre diameter and assuming the lattices are hexagonally based, Weinbaum and colleagues (30-31) have developed a model for molecular sieving through the glycocalyx that corresponds closely to the observed molecular sieving properties of microvascular walls. This model, however, predicts values compatible with estimates of the glycocalyx contribution to hydraulic permeability (LP) when the glycocalyx thickness is 100-150nm. Increasing the thickness of the glycocalyx to 400-600nm reduces the LP by a factor of three to six fold. Our preliminary calculations for filtration through a square-based lattice lead us to similar conclusions. Curry & Adamson (2011)(3) suggest that the outer region of the glycocalyx, absent from our preparations, has relatively high permeabilities to water and proteins. Evidence consistent with the endocapillary layer having an inner highly restrictive region and outer more porous region has been reported by Gao and Lipowsky (2010)(6), who estimated diffusion coefficients (D) of fluorescein through an endo-capillary layer 460nm thick and through its innermost 173nm. If the exclusion of macromolecules followed a similar pattern, however, it would conflict with the Vink- Duling observations that larger dextran and protein molecules are excluded from a near wall zone of 400-600nm in similar vessels. It seems that the difference between in vivo inferences of glycocalyx thickness and those estimates from electron micrographs may only be resolved when marker molecules identifiable in both light and EM are used on the same preparation – preferably in the same experiment. This may also highlight differences between the static case and the physiological dynamic scenario. Such experiments may also address any unknown structural alterations due to the lack of circulating plasma proteins in the short time between injection and fixation(4, 13, 24). The data obtained in this short study broadly agree with previous data (1, 23), but the method has the potential to go much further. The degree of long range order in the fibre array can be tested; the shape of the fibres can be viewed directly; any repeats along the fibres themselves can be studied; any variation in lattice order close to or further away from the membrane can be assessed. This approach promises to reveal a wealth of structural previously unobtainable detail about the glycocalyx. If combined with labelling or extraction of specific glycoproteins (for example) this approach can start to elucidate the composition and molecular disposition of the glycocalyx.

There appear to be two significant ways in which tomographic reconstructions can be helpful. Firstly with the direct measurement of lattice spacings, angles and fibre width it will be possible to define mathematical models with much more confidence and accuracy. The second approach, which cannot be achieved any other way, is to represent the tomogram as a 3D intensity array in the computer and, using randomisation methods (such as Monte Carlo techniques), to computationally filter various size macromolecules through the 3D density. With this approach the mathematical models can be tested directly against physiological data.

The current mathematical models of glycocalyx behaviour as a molecular filter depend on the presence of a lattice structure, but the presence of this structure needs to be confirmed with more data on where the lattice occurs and if there are any regions where it does not occur or is different. It may take extensive calculation to be sure of the contribution of the glycocalyx to macromolecular permeability, after the specific routes though the endothelium are taken into account.

In conclusion, a new fixation technique (LaDy GAGa) has been shown that starts to fix and stain the glycocalyx in the flush solution prior to glutaraldehyde fixation and avoids many aldehyde induced artefacts. Secondly the use of electron tomography opens up a range of new possibilities in analysing glycocalyx structure. However, we have also shown that an accurate estimate of the sample shrinkage is needed if quantitative outcomes are required. We have demonstrated for the first time that transmission electron tomography can be used to visualise the mammalian glycocalyces in 3D so that structure in any particular direction, particularly from the luminal viewpoint, can be viewed directly and investigated. In this way we have confirmed the presence of both 2D order in a luminal view and 1D order along the fibres in a vertical view and that the latter is real and not a Moiré effect. Spacing measurements of around 20 nm in the glycocalyx lattice, with fibre diameters around 10 to 12 nm are now consistently obtained. The contents of the ‘unit cells’ of the paracrystalline glycocalyx lattice now need to be determined.

Perspectives.

Understanding the transport across capillary walls is vital for understanding the function of the microcirculation. Dysfunction is a symptom many diseases, highlighted by protein urea in diabetes and heart disease. This manuscript aims to show how modern microscopy techniques can give new insights into the structure of the glycocalyx, an important permeability component of the capillary wall.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was supported by British Heart Foundation PG/08/059/25335, MRC grant GR0600920 and the Richard Bright VEGF Research Trust.

References

- 1.Arkill KP, Knupp C, Michel CC, Neal CR, Qvortrup K, Rostgaard J, Squire JM. Similar endothelial glycocalyx structures in microvessels from a range of mammalian tissues: Evidence for a common filtering mechanism? Biophysical Journal. 2011;101:1046–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowther RA, Derosier DJ, Klug A. Reconstruction of 3 dimensional structure from projections and its application to electron microscopy. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 1970;317:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry FE, Adamson RH. Endothelial glycocalyx: Permeability barrier and mechanosensor. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florian JA, Kosky JR, Ainslie K, Pang ZY, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a mechanosensor on endothelial cells. Circulation Research. 2003;93:E136–E142. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000101744.47866.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujikawa S. Tannic-acid improves the visualization of the human-erythrocyte membrane skeleton by freeze-etching. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1983;84:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(83)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao LJ, Lipowsky HH. Composition of the endothelial glycocalyx and its relation to its thickness and diffusion of small solutes. Microvascular Research. 2010;80:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayat MA. Fixation for electron microscopy. Academic Press; New York: 1981. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjalmarsson C, Johansson BR, Haraldsson B. Electron microscopic evaluation of the endothelial surface layer of glomerular capillaries. Microvascular Research. 2004;67:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using imod. Journal of Structural Biology. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luther PK, Lawrence MC, Crowther RA. A method for monitoring the collapse of plastic sections as a function of electron dose. Ultramicroscopy. 1988;24:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(88)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantell JM, Verkade P, P. AK. Quantitative biological measurement in transmission electron tomography. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Accepted 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mastronarde DN. Dual-axis tomography: An approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. Journal of Structural Biology. 1997;120:343–352. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel CC, Phillips ME, Turner MR. The effects of native and modified bovine serum-albumin on the permeability of frog mesenteric capillaries. Journal of Physiology. 1985;360:333–346. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng L, Grodzinsky LJ, Sandy J, Plaas A, Ortiz C. Persistence length of cartilage aggrecan macromolecules measured via atomic force microscopy. Macromolecular Symposia. 2004;214:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pigino G, Geimer S, Lanzavecchia S, Paccagnini E, Cantele F, Diener DR, Rosenbaum JL, Lupetti P. Electron-tomographic analysis of intraflagellar transport particle trains in situ. Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;187:135–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qvortrup K, Rostgaard J. Ultrastructure of the endolymphatic duct in the rat - fixation and preservation. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1993;113:731–740. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasband WS. Imagej. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997-2009. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostgaard J, Qvortrup K. Electron microscopic demonstrations of filamentous molecular sieve plugs in capillary fenestrae. Microvascular Research. 1997;53:1–13. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rostgaard J, Qvortrup K. Sieve plugs in fenestrae of glomerular capillaries - site of the filtration barrier? Cells Tissues Organs. 2002;170:132–138. doi: 10.1159/000046186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rostgaard J, Qvortrup K, Poulsen SS. Improvements in the technique of vascular perfusion-fixation employing a fluorocarbon-containing perfusate and a peristaltic pump controlled by pressure feedback. Journal of Microscopy. 1993;172:137–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1993.tb03405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schindelin J. Fiji is just ImageJ (batteries included). Proceedings of the 2nd ImageJ User & Developer Conference; 2008; Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ML, Long DS, Damiano ER, Ley K. Near-wall mu-piv reveals a hydrodynamically relevant endothelial surface layer in venules in vivo. Biophysical Journal. 2003;85:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Squire JM, Chew M, Nneji G, Neal C, Barry J, Michel C. Quasi-periodic substructure in the microvessel endothelial glycocalyx: A possible explanation for molecular filtering? Journal of Structural Biology. 2001;136:239–255. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thi MM, Tarbell JM, Weinbaum S, Spray DC. The role of the glycocalyx in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton under fluid shear stress: A “Bumper-car” Model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16483–16488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JAE. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circulation Research. 2003;92:592–594. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065917.53950.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vink H, Duling BR. Capillary endothelial surface layer selectively reduces plasma solute distribution volume. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000;278:H285–H289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vink H, Duling BR. Identification of distinct luminal domains for macromolecules, erythrocytes, and leukocytes within mammalian capillaries. Circulation Research. 1996;79:581–589. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner RC, Chen SC. Ultrastructural distribution of terbium across capillary endothelium: detection by electron spectroscopic imaging and electron-energy loss spectroscopy. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 1990;38:275–282. doi: 10.1177/38.2.2299181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinbaum S, Tarbell JM, Damiano ER. The structure and function of the endothelial glycocalyx layer. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2007;9:121–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinbaum S, Zhang XB, Han YF, Vink H, Cowin SC. Mechanotransduction and flow across the endothelial glycocalyx. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7988–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332808100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang XB, Curry FR, Weinbaum S. Mechanism of osmotic flow in a periodic fiber array. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;290:H844–H852. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00695.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]