Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate the healthcare utilization of hospitalized children with hypertension. The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids' Inpatient Database, years 1997, 2000, 2003, and 2006, was used to identify hypertension hospitalizations. We examined the association of patient and hospital characteristics on hypertension charges. Data from each cohort year were used to analyze trends in charges. We found that 71282 pediatric hypertension hospitalizations generated $3.1 billion in total charges from 1997 to 2006. Approximately 68% were 10 to 18 years old, 55% were boys, and 47% were white. Six percent of claims with a diagnosis code for hypertension also had a diagnosis code for end-stage renal disease or renal transplant. The frequency of hypertension discharges increased over time (P=0.02 for each of age groups 2–9 years and 2–18 years; P=0.03 for age group 10–18 years), as well as the fraction of inpatient charges attributed to hypertension (P<0.0001). Length of stay and end-stage renal disease were associated with increases in hospitalization associated charges (P<0.0001 and P=0.03, respectively). During the 10-year study period, the frequency of hypertension-associated hospitalizations was increasing across all of the age groups, and the fraction of charges related to hypertension was also increasing. The coexisting condition of end-stage renal disease resulted in a significant increase in healthcare charges.

Keywords: pediatrics, blood pressure, fees and charges, kidney failure, chronic

Hypertension is present in 1% to 3% of children in the United States.1–3 This prevalence has been rising over the past decades. Increasingly, cardiovascular sequelae of pediatric hypertension are manifesting, including left ventricular hypertrophy, increased carotid intima-media thickness, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood.4–6

Epidemiological studies have examined the national economic burden of hypertension in adults.7,8 In 1998, the healthcare cost in hypertensive adults was $46 billion in inpatients and at least $28 billion in outpatients.8 Of the total expenditures attributed to hypertension in adults, hospitalizations accounted for the largest proportion (42%) of the total cost, followed by physician services, medications, nursing home care, and home care services.8 Little is known about the economic burden of pediatric hypertension. In a selected population of obesity-related pediatric hypertension, 1 study examined the total Medicaid healthcare cost including outpatient and inpatient services in South Carolina.9 However, no previous publications have addressed the inpatient healthcare charges for children with hypertension inclusive of all payer types.

We elected to investigate the inpatient healthcare utilization associated with pediatric hypertension using nationally representative inpatient data.10 Our primary objective was to evaluate the frequency of hypertension discharges and the economic burden of inpatient care for children with hypertension. Our secondary objective was to identify demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with hospitalization charges. Our third objective was to examine the relative contribution of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) to these charges.

Methods

Data Source

Pediatric discharge data for 1997–2006 were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Kids' Inpatient Database (KID), which is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.10 It is the only comprehensive, all-payer healthcare database for children in the United States. KID data are available for 1997, 2000, 2003, and 2006 and are generated by taking a 10% sample of uncomplicated live births and an 80% sample of all other pediatric discharges (age 0–18 years in 1997 and 0–20 years in 2000–2006) from community nonrehabilitation hospitals in participating states. Data from the years 1997, 2000, 2003, and 2006 were drawn from 22, 27, 36, and 38 reporting states, respectively. Included in each discharge record were International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes, patient and hospital demographics, length of stay (LOS), and HCUP-generated weighting for hospital charges based on the American Hospital Association universe of hospitals as the standard.10

Outcome Variables of Interest

The pediatric hypertension subcohort was generated by searching the 1997, 2000, 2003, and 2006 KID cohorts for all discharges with either a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypertension. Hypertension was defined as those with ICD-9 codes 401.xx to 405.xx and 437.2 (Table 1). ESRD was defined as hospitalizations having an ICD-9 code for ESRD or renal transplant. Demographic and hospitalization data extracted included patient age, race, sex, insurance type (private, public, or other), median income based on patient zip code, hospital teaching status, hospital region (South, Midwest, Northeast, and West), charge per discharge, and LOS. We combined primary and secondary payers for the insurance category. Any patient with a private payer was grouped as private. Any patient with no private payer who had a public payer was grouped as public. All others were grouped in the “other” category. In addition, we investigated the most common ICD-9 codes listed as a primary or secondary diagnosis.

Table 1.

ICD-9 Codes and Definitions Used to Categorize Hospitalizations

| Diagnosis Groups | ICD-9 Diagnosis and Procedure Codes |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 401.0, 401.1, 401.9, 402.00, 402.01, 402.10, 402.11, 402.90, 402.91, 403.00, 403.10, 403.90, 404.00, 404.01, 404.10, 404.11, 404.90, 404.91, 405.01, 405.09, 405.11, 405.19, 405.91, 405.99, 437.2 |

| ESRD | |

| Diagnosis codes | |

| ESRD | 585.5, 585.6, 585.9, 586, 403.01, 403.11, 403.91, 404.02, 404.12, 404.92, 404.03, 404.13, 404.93 |

| Renal transplant | v42.0, 996.81 |

| Procedure codes | |

| Renal transplant | 55.69, 55.53, 55.52, 55.51, 55.54 |

ICD-9 indicates International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Statistical Analysis

Sum and standard deviation were computed for discharges and charges with a primary or secondary diagnosis for hypertension. Means and standard errors were also computed for charges. Frequencies and percentages for demographic variables including age group (2–9 years and 10–18 years), race, sex, insurance status, median income by zip code, hospital teaching status, hospital region, and survey year were calculated. χ2 tests were used to assess differences between groups. Means and standard errors were computed for LOS. To account for inflation in comparison of charges over time, we converted charges from 1997, 2000, and 2003 into 2006 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.11 All of the results are shown in 2006 dollars. Linear regression models were used, including an interaction term hypertension*time, to assess the trend of fraction of charges attributed to hypertension over time. Population-adjusted rates for number of discharges by cohort year and age group (ages 2–18, 2–9, and 10–18 years) were computed with the numerator equal to the sum of discharges divided by the year-matched census population by age group. Population-adjusted standard error for number of discharges by year and age group were also computed with the numerator equal to the standard divided by the census population by age group. Linear regression models were used to assess trend of discharges by age group over time.

Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios for hypertension-related discharges. Independent variables included in the model were age group, race, sex, insurance status, median income by zip code, hospital teaching status, hospital region, and survey year. Association of patient and hospital characteristics to hypertension-related charges were assessed with linear regression. Independent variables included in the model were the same as for modeling number of discharges in addition to association of ESRD with or without renal transplant included on claims related to hypertension. All of the analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Appropriate survey weights, domain, cluster, and stratum statements were specified in all of the analyses to provide accurate national estimates and to assure unbiased variance estimates.10 All of the results are provided as weighted estimates.

Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Results

Demographics

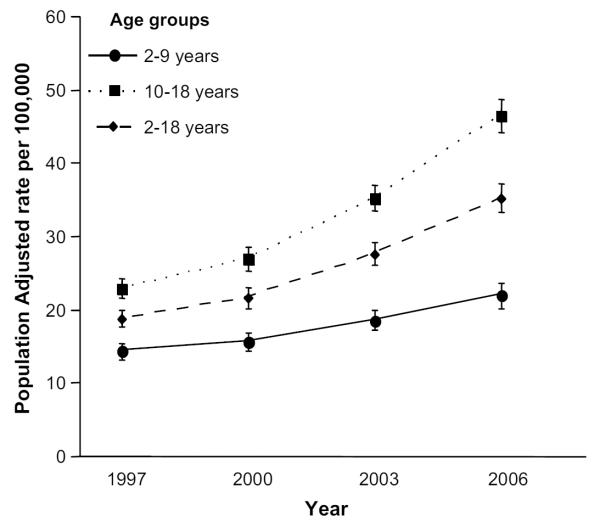

From 1997 to 2006, there were 38803 discharges with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypertension in children 2 to 18 years old, representing an estimated 71282 discharges nationally (Table 2). Children hospitalized with hypertension were more likely to be >9 years old, male, and treated in a teaching hospital (Table 3). The 3 most common diagnoses in the pediatric hospitalizations were pneumonia-organism not otherwise specified, acute appendicitis not otherwise specified, and status asthmaticus with frequencies of 3.8%, 3.0%, and 2.3%, respectively. When a hypertension diagnosis was coded as the primary diagnosis, convulsive disorder not otherwise specified, headache, obesity, and systemic lupus erythematosus were the most common secondary diagnoses with frequencies of 4.7%, 2.6%, 2.4% and 2.4%, respectively. When hypertension was in any diagnosis position, the most common primary diagnoses were systemic lupus erythematosus, complications of kidney transplant, pneumonia-organism not otherwise specified, and acute proliferative glomerulonephritis with frequencies of 3.4%, 1.9%, 1.7%, and 1.7%, respectively. Mean LOS for children with hypertension was 8 days compared with 4 days for nonhypertension pediatric discharges (P<0.0001). Total charges for hypertension-associated hospitalizations from 1997 to 2006 were $3.1 billion (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Demographic Description of Study Population Discharged From US Hospitals From 1997 to 2006

| Variable | All Pediatric Discharges Weighted, N | Non-HTN Discharges Weighted, N (%) | HTN Discharges Weighted, N (%) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of discharges | 7 521 157 | 7 449 875 | 71 282 | |

| Age, y | <0.0001 | |||

| 2–9 | 2 913 826 | 2 891 315 (38.8) | 22 510 (31.6) | |

| 10–18 | 4 607 332 | 4 558 559 (61.2) | 48 772 (68.4) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||

| Female | 4 154 334 | 4 122 302 (55.7) | 32 032 (45.0) | |

| Male | 3 316 741 | 3 277 568 (44.3) | 39 173 (55.0) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | |||

| Black | 1 102 567 | 1 087 596 (19.3) | 14 971 (27.2) | |

| Hispanic | 1 112 201 | 1 102 512 (19.5) | 9689 (17.6) | |

| Other | 390 100 | 385 665 (6.8) | 4434 (8.1) | |

| White | 3 099 265 | 3 073 339 (54.4) | 25 926 (47.1) | |

| Teaching status | <0.0001 | |||

| Nonteaching | 3 198 665 | 3 184 136 (43.3) | 14 529 (21.0) | |

| Teaching | 4 216 523 | 4 161 788 (56.7) | 54 735 (79.0) | |

| Insurance status | <0.0001 | |||

| Other | 675 525 | 669 890 (9.0) | 5635 (7.9) | |

| Private | 3 781 268 | 3 747 385 (50.4) | 33 883 (47.6) | |

| Public | 3 048 549 | 3 016 901 (40.6) | 31 648 (44.5) | |

| Income by zip code (median) | 0.9688 | |||

| 0 to 25th percentile | 2 044 936 | 2 025 436 (28.0) | 19 500 (28.2) | |

| 26th to 50th percentile | 1 894 663 | 1 876 787 (26.0) | 17 876 (25.8) | |

| 51st to 75th percentile | 1 615 682 | 1 600 228 (22.1) | 15 454 (22.3) | |

| 76th to 100th percentile | 1 738 793 | 1 722 375 (23.8) | 16 418 (23.7) | |

| Region | 0.4322 | |||

| Midwest | 1 680 413 | 1 664 878 (22.3) | 15 535 (21.8) | |

| Northeast | 1 457 366 | 1 444 650 (19.4) | 12 716 (17.8) | |

| South | 2 766 006 | 2 739 594 (36.8) | 26 411 (37.1) | |

| West | 1 617 373 | 1600 752 (21.5) | 16 620 (23.3) | |

| ESRD | 33 007 | 28 602 (0.4) | 4405 (6.2) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay, mean (SE) | 3.8 (0.04) | 3.8 (0.04) | 8.1 (0.15) | <0.0001 |

HTN indicates hypertension; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Data show the χ2 comparison between non-HTN and HTN discharges.

Table 3.

Adjusted Log Regression Analysis of Hypertension Discharges

| Variable | β (SE) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| 2–9 | −0.23 (0.01) | <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.60–0.66) |

| 10–18 | Reference | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | −0.21 (0.01) | <0.0001 | 0.65 (0.63–0.68) |

| Male | Reference | ||

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.26 (0.02) | <0.0001 | 1.45 (1.36–1.55) |

| Hispanic | −0.20 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) |

| Other | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.066 | 1.19 (1.08–1.300) |

| White | Reference | ||

| Teaching status | |||

| Teaching | 0.50 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 2.72 (2.43–3.05) |

| Nonteaching | Reference | ||

| Insurance status | |||

| Other | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.022 | 0.93 (0.88–0.97) |

| Private | −0.16 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.68–0.84) |

| Public | Reference | ||

| Income by zip code (median) | |||

| 0 to 25th percentile | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.055 | 0.92(0.84–1.01) |

| 26th to 50th percentile | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.263 | 0.98 (0.91–1.07) |

| 51st to 75th percentile | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.418 | 0.95 (0.89–1.02) |

| 76th to 100th percentile | Reference | ||

| Region | |||

| Midwest | −0.05 (0.08) | 0.534 | 0.76 (0.60–0.97) |

| Northeast | −0.24 (0.06) | <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.53–0.75) |

| South | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.121 | 0.87 (0.74–1.01) |

| West | Reference | ||

| Length of stay | 0.02 (0.001) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) |

| Cohort y | |||

| 1997 | −0.26 (0.06) | <0.0001 | 0.55 (0.47–0.64) |

| 2000 | −0.17 (0.04) | <0.0001 | 0.6 (0.55–0.65) |

| 2003 | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.006 | 0.78 (0.71–0.85) |

| 2006 | Reference |

Figure 1.

Mean hospitalization charge per discharge for all children hospitalized in the United States reported in 2006 dollars. ∎, All pediatric;  , Nonhypertension (HTN);

, Nonhypertension (HTN);  , HTN.

, HTN.

Longitudinal Evaluation of Pediatric Hypertension

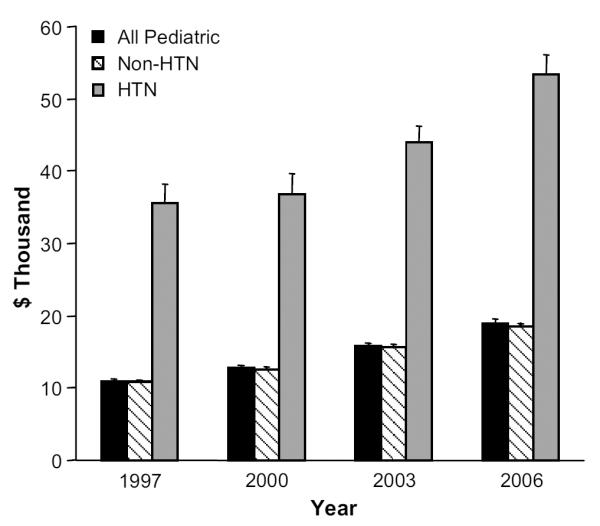

The frequency of hypertension-associated hospitalizations increased over time (P=0.02; Figure 2). Similarly, the mean charges for pediatric hospitalizations overall and with hypertension were increasing over time. The mean charge for discharges with a diagnosis of hypertension increased from $35600 in 1997 to $53500 in 2006. The fraction of all pediatric hospitalization charges associated with hypertension increased from 2.2% to 4.0% between 1997 and 2006 (P<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Discharges by age and year. P=0.02 for each of age groups 2 to 9 years and 2 to 18 years. P=0.03 for age group 10 to 18 years. ●, 2–9 years; ∎, 10–18 years; ◆, 2–18 years.

Pediatric Hospitalization Charges

Adjusted multivariate regression analysis for hypertension-associated hospitalizations indicated that charges were higher in patients 2 to 9 years old ($3200; P=0.005), with coexisting ESRD or renal transplant ($3600; P=0.03), with longer length of stay ($5500 per day; P<0.0001), and in boys ($2300; P=0.002; Table 4). Mean charges from teaching institutions were $8000 more than nonteaching institutions (P<0.0001).

Table 4.

Adjusted Multivariate Regression Analysis of Differences in Hospitalization Charges in Children With Hypertension

| Variable | β (SE) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 2–9 | 3.2 (1.1) | 0.005 |

| 10–18 | Reference | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | −2.3 (0.7) | 0.002 |

| Male | Reference | |

| Race | ||

| Black | −2.5 (1.1) | 0.019 |

| Hispanic | 3.4 (1.7) | 0.041 |

| Other | 4.0 (1.7) | 0.017 |

| White | Reference | |

| Teaching status | ||

| Teaching | 8.0 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Nonteaching | Reference | |

| Insurance status | ||

| Other | 6.8 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Private | 2.1 (1.6) | 0.183 |

| Public | Reference | |

| Income by zip code (median) | ||

| 0 to 25th percentile | −3.9 (1.5) | 0.010 |

| 26th to 50th percentile | −2.9 (1.6) | 0.067 |

| 51st to 75th percentile | −1.8 (1.5) | 0.229 |

| 76th to 100th percentile | Reference | |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | −23.9 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | −23.0 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| South | −19.9 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

| West | Reference | |

| Renal status | ||

| ESRD | 3.6 (1.7) | 0.03 |

| No ESRD | Reference | |

| Length of stay | 5.5 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Cohort y | ||

| 1997 | −18.8 (2.8) | <0.0001 |

| 2000 | −17.4 (2.3) | <0.0001 |

| 2003 | −7.6 (2.6) | 0.003 |

| 2006 | Reference |

Values are expressed in 2006 dollars ($ thousand). ESRD indicates end-stage renal disease.

Discussion

This article represents the first step toward a better understanding of inpatient healthcare utilization in children with hypertension. Mean hospitalization charges for children with hypertension have increased by 50% and account for an estimated $3.1 billion in inpatient healthcare charges from 1997 to 2006. The frequency of hypertension discharges rose significantly in children. Other published studies have demonstrated an increase in frequency of hypertension among children in outpatient and community settings in the United States.12,13 Taken together, one might postulate that a fraction of all cases of hypertension may be hospitalized, and the increase in hypertension in the outpatient setting is directly related to observed trends in the inpatient environment.

Our study found a higher frequency of hypertension discharges in 10- to 18-year olds as compared with 2- to 9-year olds. One may hypothesize that the higher frequency of hypertension discharges seen in the 10- to 18-year–old group in our study may be because of the rise in obesity prevalence as reported in the literature, especially among adolescents.14,15 Several studies have demonstrated an association between childhood obesity and pediatric hypertension.13,16 Sorof and Daniels17 reported that children who are obese are at 3-fold higher risk of developing hypertension than nonobese children. Although we found that only 9.3% of claims with hypertension also have a code for obesity, of those with obesity and hypertension jointly coded, 9% were 2 to 9 years old and 91% were 10 to 18 years old. Analyses using discharge data may be limited by the accuracy of coding, which could affect the ability to identify obesity. This may be especially relevant because obesity is not typically reimbursable, thereby resulting in a lower likelihood of coding obesity as a discharge diagnosis.18,19 The KID database does not capture body mass index data. These data would be required to further explore this potential association.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors were examined as potential determinants of hypertension healthcare utilization. We found that boys and blacks were more likely than girls and other races to be hospitalized with hypertension. This is consistent with pediatric studies in the outpatient setting and studies in adults.12,13 Blacks have been shown to be at higher risk of hypertension across the life span and, therefore, may be at increased risk for hypertension-associated hospitalizations. In addition, blacks have a blunted nocturnal dip, which may contribute to an increased cardiovascular load compared with white Americans.20–22 Our study analyzed median income by zip code as the marker of socioeconomic status. We did not find an association, but this may have reflected the insensitive nature of this socioeconomic status surrogate.

A few studies have examined medical expenditures of pediatric hypertension in the ambulatory setting.9,23 Swartz et al23 investigated the cost effectiveness of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the evaluation of 267 children with hypertension in a single medical center between 2005 and 2006. The charge for outpatient evaluation of a hypertensive child was $3420 for the initial evaluation. In a study comparing total cost of obesity-related pediatric hypertension with a randomly selected control group in the South Carolina Medicaid system, the costs of outpatient and inpatient services were significantly higher in the obese hypertensives compared with the controls ($28596 versus $15242).9 Although our analysis was restricted to the available inpatient charge data, our results are reflective of all payer types and all causes of pediatric hypertension.

Although there are numerous studies evaluating the trends of hypertension prevalence among children in outpatient settings, to our knowledge, there have been no published reports on inpatient healthcare utilization for pediatric hypertension and the contribution of ESRD to inpatient charges. In adults, the total US expenditure in 1998 attributable to hypertension was $108.8 billion.8 Of this total, 21% was attributed to a hypertension diagnosis, 27% to a cardiovascular condition, and 52% to all other conditions. Although ESRD was included in the all other conditions group, the exact contribution of ESRD to the overall hypertension expenditure remains unclear.8 Thamer et al24 examined medical care costs among adults with renal failure, including those with chronic renal failure and ESRD in 1991. They found that hypertensive patients with renal failure were 10 times more likely to be hospitalized, and their LOS was ≈1 day longer than patients without renal failure. Our findings among pediatric hospitalizations are similar to the existing adult data in that hypertensive children with ESRD tend to have a significant increase in charges.

With multivariate analysis, younger age, male sex, other insurance status, and care at a teaching institution were all associated with higher charges. It is likely that patients treated at teaching institutions have more severe disease and complications, requiring more complex health care. In addition, those with “other” insurance status may represent a population that is paying out of pocket, which may also incur greater expense in comparison with patients with some form of insurance-based discount.25–27 In this study, those in the lowest median income by region and blacks had lower charges compared with the reference groups. Using the US government census data, 38% of children were in the low income bracket in 2006.28 In comparison, ≈30% of pediatric hypertension hospitalizations occurred in the lowest median income by zip code. We found that the LOS was approximately a half-day shorter for those with the lowest compared with the highest median income by zip code. The underlying cause for this LOS difference requires additional study but may explain the charge differential found in the multivariate analysis. Nearly 30% of discharges with a diagnosis of hypertension in the HCUP-KID were black compared with the 15% in the US census.28 The present study found that the LOS for blacks was slightly shorter compared with whites (7.9 days and 8.1 days, respectively). The lower hypertension charges associated with black children may be because of the possibility that these patients have poorer control in the home environment and, therefore, require more frequent, shorter hospitalizations.

The greatest strength of this study was the magnitude of the KID database. The use of a national billing claims database offered data not limited by single-center or single-payer biases. In addition, it provided a large amount of data that allowed us to move beyond demographics and to examine complicated hypertension represented as ESRD and its contribution to charges.

This study had several limitations. First, KID-weighted estimates is a limitation in our analysis of trends. This is especially true for 1997 and 2000, in which only 22 and 27 states reported, respectively. In addition, certain states regularly restrict their participation in HCUP-KID, including Georgia, Virginia, Michigan, and Illinois. Although generating sampling weights using the American Hospital Association universe of hospitals reasonably corrects for these sampling restrictions, the estimates would likely have a better representation if reporting was more uniform. It is important to understand these differences in sampling frame and data collection when using the KID for trend analysis.10 Other potential confounding factors in the increase in healthcare expenditure noted in this study include recommendations to use emerging costly technologies to evaluate hypertension, such as computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and sleep studies.29 The HCUP-KID database does not provide data on specific resources used for care of patients. In 2004, the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents provided new management guidelines that have significantly changed the approach to children with elevated blood pressure.30 These guidelines may have had significant impact on healthcare utilization, especially on screening and recognition of hypertension. This study found an increase in hypertension-related discharges at teaching hospitals, whereas those in nonteaching hospitals remained relatively constant. The increases in hospital charges in teaching institutions compared with nonteaching environments may in part reflect differential case ascertainment.

As with other studies using data derived from medical claims, this study may be limited by the accuracy and consistency of medical biller coding. Our decision to keep the examination of hypertension ICD-9 codes broad was attributed to the possible subjectivity of the person assigning billing code, making it difficult to decipher primary hypertension from secondary hypertension. Perhaps this distinction can be better made with the new ICD-10 coding system.

Another limitation of this study is the availability of only inpatient information within KID. These discharge data include repeat hospitalizations and, thus, do not reflect unique patients. As a result, we cannot make conclusions on prevalence of pediatric hypertension or on medical care charges per capita. In addition, these data reflect charges and not actual cost of treating pediatric hypertension.

Perspectives

Healthcare utilization studies help us to understand the magnitude and economic burden of health conditions. This study expands our understanding of the impact of hypertension in children in the hospital setting and augments previous ambulatory literature. Children with hypertension in the inpatient setting are likely to have either severe hypertension or hypertension that complicates a coexisting condition. This study shows that, across this inpatient landscape, the frequency of hypertension hospitalizations is rising, the fraction of charges attributed to hypertension are increasing, and hospitalization of children with hypertension and ESRD resulted in significant increases in healthcare charges. A more detailed evaluation of resource use for hypertensive children in the outpatient setting will complement this study to provide a more complete description of hypertension-related healthcare utilization and charges.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

This study expands our understanding of inpatient pediatric hypertension-related healthcare utilization.

What Is Relevant?

Pediatric hypertension-related hospitalizations have increased ≈2-fold from 12661 discharges in 1997 to 24602 in 2006.

In hypertensive children, the total inpatient healthcare charges were $3.1 billion between years 1997 and 2006, and total outpatient charges are unknown.

Summary

The frequency of hypertension hospitalizations is rising, fraction of charges attributed to hypertension are increasing, and hospitalization of children with hypertension and ESRD results in significant increases in healthcare charges.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colton Jackson (Rocky Vista College of Osteopathic Medicine, Parker, CO) for his assistance with this work.

Sources of Funding This work was supported by Research Training in Pediatric Nephrology grant 6 T32 DK065517-07.

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Ostchega Y, Carroll M, Prineas RJ, McDowell MA, Louis T, Tilert T. Trends of elevated blood pressure among children and adolescents: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey 1988–2006. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:59–67. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkner B, Daniels SR. Summary of the fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Hypertension. 2004;44:387–388. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143545.54637.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, Franco KD, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Prevalence of hypertension and pre-hypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150:640–644. 644, e641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn JT. Pediatric hypertension: recent trends and accomplishments, future challenges. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:605–612. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauer RM, Clarke WR. Childhood risk factors for high adult blood pressure: the Muscatine Study. Pediatrics. 1989;84:633–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Maki-Torkko N, Jarvisalo MJ, Uhari M, Jokinen E, Ronnemaa T, Akerblom HK, Viikari JS. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. JAMA. 2003;290:2277–2283. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balu S, Thomas J., III Incremental expenditure of treating hypertension in the United States. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.12.013. discussion 817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgson TA, Cai L. Medical care expenditures for hypertension, its complications, and its comorbidities. Med Care. 2001;39:599–615. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerrell JM, Sakarcan A. Primary health care access, continuity, and cost among pediatric patients with obesity hypertension. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:223–228. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hcup Kids' Inpatient Database (KID) Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2006 and 2009. [Accessed June 13, 2010]. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics: consumer price index. http://www.Bls.Gov/cpi/

- 12.Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116:1488–1496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in us children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falkner B, Gidding SS, Ramirez-Garnica G, Wiltrout SA, West D, Rappaport EB. The relationship of body mass index and blood pressure in primary care pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;148:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40:441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032940.33466.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolford SJ, Gebremariam A, Clark SJ, Davis MM. Incremental hospital charges associated with obesity as a secondary diagnosis in children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1895–1901. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tershakovec AM, Watson MH, Wenner WJ, Jr, Marx AL. Insurance reimbursement for the treatment of obesity in children. J Pediatr. 1999;134:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harshfield GA, Alpert BS, Willey ES, Somes GW, Murphy JK, Dupaul LM. Race and gender influence ambulatory blood pressure patterns of adolescents. Hypertension. 1989;14:598–603. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Profant J, Dimsdale JE. Race and diurnal blood pressure patterns: a review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 1999;33:1099–1104. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Poole JC, Treiber FA, Harshfield GA, Hanevold CD, Snieder H. Ethnic and gender differences in ambulatory blood pressure trajectories: results from a 15-year longitudinal study in youth and young adults. Circulation. 2006;114:2780–2787. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swartz SJ, Srivaths PR, Croix B, Feig DI. Cost-effectiveness of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the initial evaluation of hypertension in children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1177–1181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thamer M, Ray NF, Fehrenbach SN, Richard C, Kimmel PL. Relative risk and economic consequences of inpatient care among patients with renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:751–762. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V75751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuntze C. Insured versus uninsured: the fight for equal pricing in health care. J Leg Med. 2008;29:537–552. doi: 10.1080/01947640802494887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson GF. From `soak the rich' to `soak the poor': recent trends in hospital pricing. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:780–789. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melnick GA, Fonkych K. Hospital pricing and the uninsured: do the uninsured pay higher prices? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w116–w122. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau [Accessed March 1, 2012];America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. 2011 http://www.Childstats.Gov/americaschildren/tables.Asp.

- 29.National High Blood Pressure Education Program . The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2004. Report No. 04-5230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The fourth report on the diagnosis The fourth report on the diagnosis, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]