Social media provides a stream of real-time, user-generated updates from millions of people globally. What can Google and Twitter behavior teach us about migraine?

With Google trends (http://www.google.com/trends/) we determined the relative number of “migraine” searches in the United States between 1 January 2007 and 31 July 2012 There were significantly more searches for “migraine” during weekdays than during weekends and holidays like Thanksgiving and Memorial Day (p <0.00001), consistent with studies indicating a decreased risk of migraine attacks on days o3 (1). During the working week, Tuesdays had the highest (p = 0.02) and Fridays the lowest (p = 0.00009) frequency of searches.

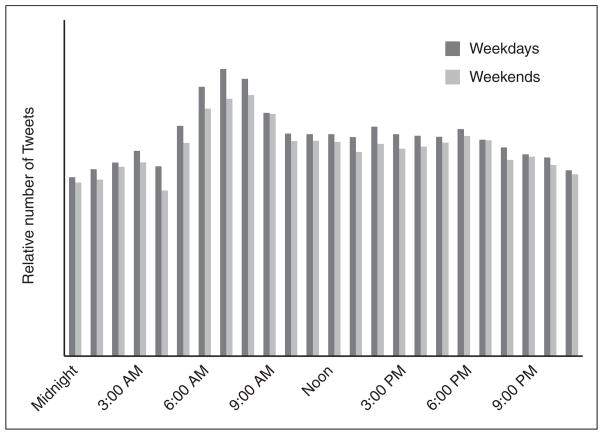

Second, we used a publicly available online tool —timeuse (http://timeu.se/) — that consists of a timestamped searchable bank of millions of Twitter messages (2). “Migraine” was Tweeted significantly more on weekdays than on weekends (p = 0.00003). During the working week, Monday had the highest and Friday the lowest frequency, and Tweets were most common around 7 a.m. (See Figure 1.) This is consistent with a study on migraine attacks in patients, where these peaked between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. (3). On a population basis, the Tweeting of the terms “stress” and “migraine” were most correlated when the stress time series was lagged two hours (r = 0.67).

Figure 1.

Tweets of “Migraine” across the day.

“Headache” Tweets peaked at 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. during the working week, and at 9:30 on weekend mornings. “Headache” was Tweeted around six times more often than “migraine.” In 100 sampled Twitter reports of migraine, 81 were from women, 17 were from men and two were without identifiable gender. Both the ratio between headache and migraine, and the ratio between men and women, are comparable to results from large-scale epidemiological studies (4).

Many of the sampled Tweets described frustration, symptoms, disease duration, medications and suspected triggers. An in-depth analysis of time series of Tweets by individual migraineurs may provide information on triggers such as sleep deprivation, stress and foods, as may analysis of Google searches and Tweets in relation to sunlight, temperature, latitude (5), cultural events or even barometric pressure. We conclude that online behavior is a rich, free source of voluntary self-reports that can enrich or supplement epidemiological and diary studies on disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grants 1R01NS073997 and 1R01NS075018-01A1.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Alstadhaug KB, Salvesen R, Bekkelund S. Weekend migraine. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:343–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golder SA, Macy MW. Diurnal and seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength across diverse cultures. Science. 2011;333:1878–1881. doi: 10.1126/science.1202775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox AW, Davis RL. Migraine chronobiology. Headache. 1998;38:436–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3806436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, et al. Epidemiology of headache in a general population — a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang AC, Huang NE, Peng CK, et al. Do seasons have an influence on the incidence of depression? The use of an internet search engine query data as a proxy of human affect. PloS One. 2010;5:e13728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]