Abstract

Angiogenesis is an effective target in cancer control. The anti-angiogenic efficacy and associated mechanisms of acacetin, a plant flavone, is poorly known. In the present study, acacetin inhibited growth and survival (upto 92%, p<0.001), and capillary-like tube formation on matrigel (upto 98%, p<0.001) by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in regular condition, as well as VEGF-induced and tumor cells conditioned medium-stimulated growth conditions. It caused retraction and disintegration of preformed capillary networks (upto 91%, p<0.001). HUVEC migration and invasion were suppressed by 68-100% (p<0.001). Acacetin inhibited Stat-1 (Tyr701) and Stat-3 (Tyr705) phosphorylation, and down-regulated pro-angiogenic factors including VEGF, eNOS, iNOS, MMP-2 and bFGF in HUVEC. It also suppressed nuclear localization of pStat-3 (Tyr705). Acacetin strongly inhibited capillary sprouting and networking from rat aortic rings and fertilized chicken egg chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) (~71%, p<0.001). Furthermore, it suppressed angiogenesis in matrigel plugs implanted in Swiss albino mice. Acacetin also inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat-1 and Stat-3, and expression of VEGF in cancer cells. Overall, acacetin inhibits Stat signaling and suppresses angiogenesis in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo, and therefore, it could be a potential agent to inhibit tumor angiogenesis and growth.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, acacetin, HUVEC, VEGF, bFGF, angioprevention

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels and capillaries either de novo or from the pre-existing ones, and is an important target in the treatment and management of solid tumors (1). Besides playing an important role in the normal embryonic development, angiogenesis is involved in many adult physiological processes like tissue remodeling during wound healing, female endometrial development as well as few pathologies like atherosclerosis, macular degeneration, psoriasis, tumor growth and metastasis. Onset of angiogenesis breaks down tumor dormancy and tumors enter in to an active state of growth (1-3). Solid tumors cannot grow beyond 2-3 mm diameter due to limits of diffusion for nutrients, metabolic wastes and gases, and resume active growth only when new vasculature is recruited facilitating nutrients and gaseous exchange to support tumor growth (2,3). Tumor vasculature is a prognostic marker and predictor of stages and malignant potential of a tumor (4,5). Tumor vasculature is leaky and supported by less number of pericytes, hence, making tumors prone to physiological concentrations of inhibitory agents. So, targeting angiogenesis could be one of the promising anti-angiogenic or angiopreventive strategies in cancer management (6-8). Angiogenesis involves critical steps including vasodilation, endothelial permeability, periendothelial support, endothelial cell proliferation, migration, survival and subsequent organization and remodeling into three-dimensional network of tubular structures (9,10). Hence, efficacy of anti-angiogenic agents could be directly correlated with the extent and number of these steps being targeted.

Many anticancer agents target tumor angiogenesis in their overall efficacy, and dedicated efforts to this field have led to the identification of novel anti-angiogenic agents; a few of these have been approved by FDA and some are at different stages of clinical trials (11-13). Radiation-and chemo-therapies of cancer are often associated with the burden of high cost, serious side effects, toxicity and tumor relapse; therefore, approaches that are safe, non-toxic, cost-effective, mechanism-based and easily available are desired to control tumor growth and progression. Asian populations show lesser risk of acquiring various types of cancers including prostate cancer (PCa) than their western counterparts and has been linked to the larger consumption of vegetarian diets including fruits and vegetables (14-16). Attenuating effects of this fruitarian and vegetarian life style on the risks of acquiring specific cancers has been attributed to the presence of certain novel phytochemicals that modulate signaling pathways deregulated in cancer (11,17). From a decade, now phytochemicals have been the prime focus of scientific investigations for anticancer and anti-angiogenic activities (11,17,18).

Present study evaluates the role of acacetin, an O-methylated flavone present in plants like Robinia pseudoacacia (black locust) and Turnera diffusa (damiana), as an anti-angiogenic agent. We and others have shown that acacetin possesses anticancer activity against many types of cancer cells including T-cell leukemia, lung, prostate and breast cancer (19-25); however, its anti-angiogenic activity is poorly known. One study reported that acacetin inhibits ovarian cancer cell-induced angiogenesis in CAM assay (26). Herein, we evaluated its anti-angiogenic efficacy and associated mechanisms using well established models in vitro, ex-vivo and in vivo. Our results suggest that acacetin possesses strong and promising anti-angiogenic activity and inhibits various aspects and stages of angiogenesis process.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

HUVEC and EGM2-MV basal or complete growth media were from Lonza Walkersville Inc. (Walkersville MD), human lung carcinoma cell line A549 and human PCa (22Rv1, DU145 and PC3) cell lines were from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). HUVEC was used within one year of its procurement, and all four cancer cell lines were obtained during 2008, and tested and authenticated by DNA profiling for polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) markers at University of Colorado Cancer Center DNA Sequencing & Analysis Core most recently in August 2010. RPMI 1640 media, antibiotic-antimycotic cocktail and other culture reagents for tumor cell growth were from HiMedia Laboratories, India. Fetal bovine serum was procured from HyClone-Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere in 5% CO2 at 37°C temperature. Anti-VEGF antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); VEGF and complete cocktails of protease and phosphatase inhibitors were from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Other specific primary and HRP-linked secondary antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA). ECL was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Acacetin (Fig. 1A; dissolved in DMSO as 100 mM stock solution) and AG490 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Matrigel was from BD Biosciences (San Jones, USA). Fertilized chicken eggs for CAM assay were procured from Government Poultry Farm, Chandigarh, Punjab, India.

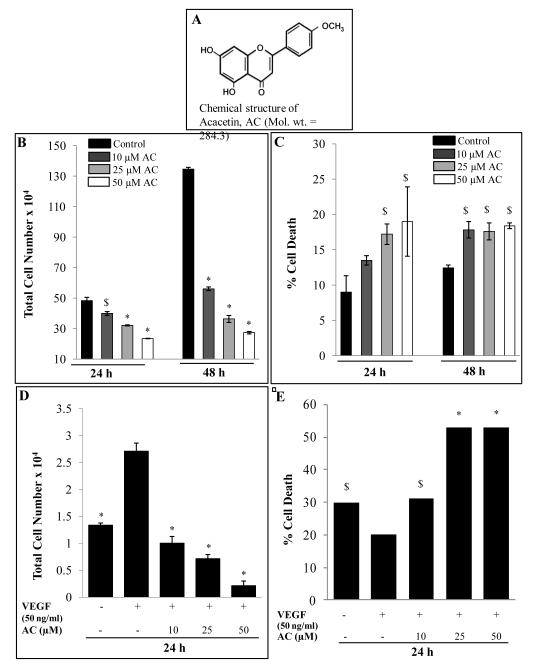

Figure 1.

Effect of acacetin on HUVEC growth and proliferation. A: Chemical structure of acacetin (AC). B-C: HUVEC proliferation and death after 24 and 48 h of AC treatment. Cells were grown in complete EGM-2MV media with 5% FBS at the density of 1× 105 cells/60 mm culture plates. After 24 h of seeding, cells were treated with 10-50 μM concentrations of AC for 24-48 h in regular growth conditions. At the end of the experiment, cells were harvested and counted using trypan blue as mentioned in Methods. Total cell number and percent dead cells versus control are shown. D-E: Effect of acacetin on VEGF-stimulated HUVEC proliferation and death. HUVEC were cultured at the density of 20,000 cells/12-well plates for 24 h time followed by serum-starvation overnight before treatment with the indicated doses of AC in serum-free medium supplemented with or without VEGF for 24 h as discussed in Methods. Total cell number and percent dead cells versus control are shown. The quantitative data shown are Mean ± SE of three samples for each treatment. Equal volumes of DMSO (0.1%, v/v) were present in each treatment. $, p<0.05; *, p<0.001 versus DMSO control or VEGF-alone treatment.

Cell growth and death assay

For cell growth and death assays, HUVEC were seeded at the density of 2 × 104 or 1 × 105 per 35-mm or 60-mm plate, respectively, in EGM-2MV complete medium, and were treated with either DMSO or indicated concentrations of acacetin for the desired time periods. In ligand-stimulated experiments, HUVEC were seeded in 12-well plates in regular medium and after 24 h growth factors and serum-starved overnight followed by treatment with VEGF and/or acacetin. Cells were collected and processed for scoring total and dead cells by trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Equal volume of DMSO (0.1% v/v) was present in each treatment in all the experiments. Data are represented as mean ± SE of triplicate samples, and repeated with similar findings.

In vitro angiogenesis assay on matrigel

To examine the effect of acacetin on in vitro angiogenesis, two methods were employed. In first method, HUVEC (4 × 104 cells/well) were simultaneously seeded with acacetin in 24-well matrigel-coated plates in EGM-2MV complete media, and tube formation was observed and quantified periodically over specific time periods under phase contrast microscope. In second protocol, acacetin treatment was carried out 6 h after initial cell seeding. In ligand-induced tube formation, 20,000 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and after overnight starvation, treated with acacetin and/or VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 16 h. Tubular network was photographed at 100x magnification and scored by either counting the number of closed structures made by three or more independent cells as one tube; or counting the trisections where at least 3 cells meet together employing an inverted microscope equipped with Zuiko digital camera (Olympus Imaging Corp., Japan). In tumor cells conditioned media (TCM)-stimulated assays, freshly collected TCM at 50% strength (50:50 with basal EGM2-MV) was used to stimulate capillary growth in presence or absence of different concentrations of acacetin. For this, serum-free conditioned media were collected after 24 h from 70% confluent A549 cells. Data are represented as mean ± SE of triplicate samples, and repeated two-three times with similar findings.

Wound closure assay

For cell motility assay, HUVEC were plated in 6-well dishes in complete EGM-2MV medium and treated with different concentrations of acacetin for 24 h followed by wounding and change of treatment media with fresh serum-free media containing only mitomycin C (5 μg/ml). Wound closure was recorded by photography at 0 and 16 h after injury using an inverted microscope equipped with Zuiko digital camera at 100x magnification. Five independent areas in each wound (in duplicates) were measured and data represented as their mean ± SE, and repeated with similar findings.

Boyden chamber matrigel invasion and migration assay

HUVEC (3 × 104) were seeded in upper chamber of matrigel-coated Boyden inserts (with 8 micron pore size) and allowed to adhere for 3 h. Cells were treated with acacetin in serum-free conditions and allowed to invade and migrate for 16 h towards the lower chamber filled with complete medium. The inserts were processed for counting the invaded/migrated cells at the bottom of the membrane as published (12). Photographs (200 × magnification) were taken by inverted microscope equipped with Zuiko digital camera. Experiment was repeated with similar findings.

Immunoblot analysis

HUVEC were grown to 70% confluency and treated with the desired concentrations of acacetin for 24 h. At the end of the treatments, cell lysates were prepared in non-denaturing lysis buffer and protein concentrations determined as published (27). Cancer cells were grown in regular conditions and treated with acacetin as indicated in the figures, and cell lysates were prepared (27). Protein lysate (50-80 μg) resolved on 10%, 12% or 15% SDS PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with specific primary antibodies followed by detection with HRP-conjugated appropriate secondary antibodies employing ECL detection system. Experiments were done two-three times with similar results.

Rat aortic ring angiogenesis assay

To assess the effect of acacetin on ex vivo angiogenesis in an organotypic blood vessel culture, 6-week old male Wistar rats, approved from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, were sacrificed and aortae were retrieved after surgery. Aortae were rinsed profusely with antibiotic cocktail solution (1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution in 1x phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) and surrounding fibro-adipose tissue was gently removed with the scalpel under sterile condition. Aortae were cut into 1 mm thick sections with sharp scalpel, and implanted on matrigel-coated tissue culture plates. Additional thin layer of matrigel was layered onto individual rings to embed them, and plates kept for 15 minutes in incubator in humidified atmosphere followed by feeding with the complete EGM-2MV media for two days and then treatment with specific concentrations of acacetin every 48 h for 2 weeks. After treatment time was over, media was removed and plates washed with 1x PBS and photographed at 200x magnification under the phase contrast microscope.

Chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) angiogenesis assay

CAM assay was performed to assess the effect of acacetin on blood vessel formation and networking in developing fertilized chicken eggs under in vivo-like conditions. Eggs were incubated in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C in humid conditions for two days. On day 3, a small hole was introduced at the pointed end of the egg to remove 1 ml albumin and later sealed with cello-tape and kept in incubator. After 48 h of incubation, 1×1 centimeter window was made to expose the CAM and closed by transparent tape. Next day (on day 6), acacetin (50 μM final conc.) was mixed with 15 μl matrigel and implanted on each CAM showing major blood vessels, followed by incubation till 14th day. Thereafter, CAMs were photographed using a digital camera (Nikon, Japan) with 10x optical zoom. Quantitative data for nascent vessel formation between the major blood vessels are represented as mean ± SE of total number of vessels in 5 independent areas on CAMs for each treatment. Experiment was repeated with similar results.

Immunofluorescence assay for pSTAT-3(Tyr705)

HUVEC were seeded (1 × 105 cells) onto coverslips and grown for 24 h under regular conditions followed by treatment with DMSO or indicated acacetin concentrations for desired time periods. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization with Triton X-100. Next, cells were blocked with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.15% glycine for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with specific primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides and examined under LSM780 Laser Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Germany) at Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, India, for image acquisition and processing. Five fields per sample were analyzed and imaged, and experiments were performed in duplicates. Experiment was done twice with similar observations.

In vivo angiogenesis assay

This assay was performed as described earlier (26). Male Swiss albino mice (~8 weeks old) were housed in the Central Animal House under standard conditions as approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Mice were divided into three groups (n=5/group) and subcutaneously injected with 500 μl of matrigel alone or with VEGF (50 ng/ml) and/or acacetin (25 or 50 mg/kg body weight of mouse). Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed and the matrigel plugs were removed, weighed and photographed using Nikon digital camera. Amount of hemoglobin (Hb) was measured using HEMOCOR-D kit (Crest Biosystems, Tulip Group, India) following the manufacturer’s protocol step-by-step. Body weight, diet and water consumption were monitored every 3 days.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using the Jandel Scientific SigmaStat 3.5 software. Student’s t-test was employed to assess the statistical significance of difference between control and treatment groups. A statistically significant difference was considered to be present at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Acacetin inhibits HUVEC growth and survival

Inhibiting HUVEC growth and proliferation is one of the prime aspects of antiangiogensis. Acacetin treatment to HUVEC significantly inhibited cell proliferation and survival in a dose-and time-dependant manner. Treatment with acacetin for 24 and 48 h in regular growth conditions inhibited cell proliferation by 18-51% and 58-80%, respectively, at 10-50 μM concentrations as compared to DMSO control (p<0.05-0.001) (Fig. 1B). Under similar conditions, acacetin induced cell death by 14-19% and 17-18% compared to 9% and 12% cell death in DMSO controls after 24 and 48 h, respectively, (Fig. 1C). This also indicates that the decrease in cell number could predominantly be mediated by acacetin-caused inhibition of cell proliferation.

Since, VEGF is an essential and potent mitogen for HUVEC growth, proliferation and survival; we assessed the effect of acacetin on VEGF-induced HUVEC growth and survival. VEGF treatment increased the growth as well as survival of starved-cells. Acacetin dose-dependently (p<0.001) inhibited VEGF-stimulated HUVEC growth and proliferation by 63-92% at 10-50 μM concentrations (Fig. 1D), and induced cell death by 31-53% (p<0.01) compared to 20% in VEGF treatment (Fig. 1E). Serum and growth factors-starvation of HUVEC for 24 h with an additional 24 h of starved condition during treatments increased the cell death to 30% as compared to 9% cell death in regular growth condition in control (Fig. 1C & 1E). HUVEC cell viability was inhibited by 14%-41% compared to VEGF-stimulated control after 24 h treatments under similar conditions (data not shown). These results suggest that acacetin strongly inhibits HUVEC growth, proliferation and survival in regular as well as VEGF-induced conditions.

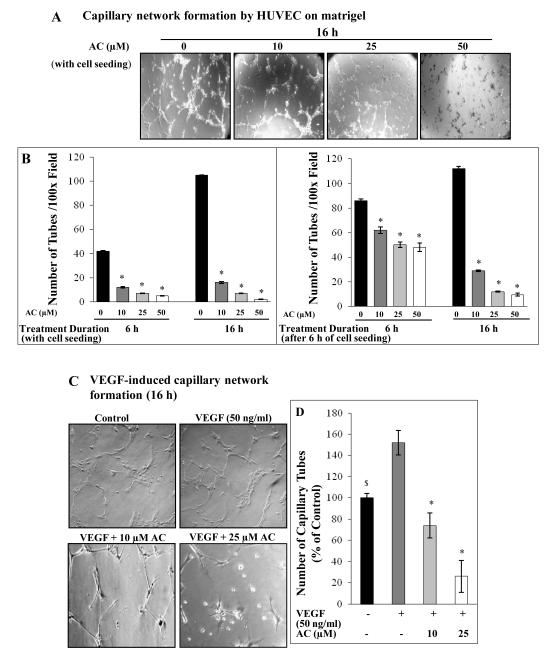

Acacetin suppresses capillary network formation on matrigel by HUVEC

Blood capillary formation is a pre-requisite step for angiogenesis process and its inhibition has been suggested as a promising approach in angioprevention and cancer control (11). Since, acacetin strongly inhibited HUVEC growth and proliferation; therefore, we next assessed its effect on HUVEC capillary-tube formation. For capillary network formation, invasion and migration assays, ≤ 24 h treatment times were used to minimize or exclude the cell death effect of acacetin on these parameters. Acacetin suppressed HUVEC capillary-tube formation in a de novo mode as well as inhibited the growth of preformed rudimentary capillaries (Fig. 2A). Under regular growth conditions, 10, 25 and 50 μM acacetin treatment at the time of HUVEC seeding inhibited tube formation by 71, 84 and 88% (p<0.001) after 6 h, and by 85, 93 and 98% (p<0.001) after 16 h, respectively (Fig. 2B). Acacetin also suppressed the growth of pre-formed rudimentary capillary tubes, in which HUVEC were seeded for 6 h under regular growth conditions resulting in rudimentary tube formation, after the treatment with 10, 25 and 50 μM acacetin. This significantly (p<0.001) disintegrated and suppressed their further growth by 28, 41 and 44% after 6 h and by 74, 89 and 91% after 16 h, respectively (Fig. 2B). Since, VEGF is an important pro-angiogenic factor stimulating HUVEC capillary-tube formation; we assessed the effect of acacetin on VEGF-stimulated HUVEC capillary-tube formation on matrigel. After seeding and overnight starvation followed by VEGF/acacetin co-treatment for 16 h, capillary-tube formation was suppressed by 51 and 83% (p<0.001) at 10 and 25 μM acacetin as compared to VEGF control, respectively (Fig. 2C-D). These findings suggest that acacetin could inhibit angiogenesis by suppressing de novo capillary-tube formation as well as disintegrating the preformed/rudimentary capillary networks in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Effect of acacetin on capillary tube formation by HUVEC on matrigel. A: Representative images depicting formation of capillary tubes on matrigel by HUVEC after 16 h treatment with AC at the time of cell seeding. B: Quantitative depiction of capillary tube formation after 6 and 16 h of AC treatment either at the time of cell seeding or after 6 h of initial cell seeding. HUVEC (4× 104 cells/well) were either simultaneously seeded and treated with AC or treatment was done after 6 h of initial cell seeding in 24-well matrigel-coated culture plates, and tube formation was observed and quantified periodically over a specific time period as mentioned in Methods. C: Representative images depicting formation of capillary-like tubes on matrigel by HUVEC after 16 h treatment with AC in VEGF-stimulated conditions. D: Quantitative data of the effect of AC treatment on VEGF-stimulated capillary tube formation by HUVEC. Cells were overnight starved and treated with AC and/or VEGF for 16 h as mentioned in Methods. Tubular network was photographed at 100x magnification and scored by counting the number of closed structure made by three or more independent cells under an inverted microscope. Quantitative data shown are Mean ± SE of three samples. $, p<0.05; *, p<0.001 versus DMSO or VEGF control.

Acacetin suppresses tumor cell conditioned media-induced capillary tube formation by HUVEC

Tumor cells secrete specific pro-angiogenic factors in the tumor microenvironment that attract the growth of new capillaries towards the tumor mass pushing tumors to high growth and metastatic progression (11). Therefore, suppressing tumor-induced angiogenesis would be a desired strategy for cancer prevention and control. Tumor cell conditioned media (TCM) is enriched with many secreted pro-angiogenic factors including VEGF, and has the potential to stimulate HUVEC capillary-tube formation on matrigel (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Therefore, TCM-stimulated angiogenesis is an important model to check the efficacy of any angiopreventive agent. We observed that acacetin potently suppressed TCM-stimulated HUVEC capillary-tube formation in a dose-dependent manner. Acacetin at 10, 25 and 50 μM concentrations significantly suppressed TCM-stimulated capillary network formation by 34, 61 and 80% after 12 h and 38, 59 and 83% after 18 h, respectively, compared to TCM control (p<0.001) (Suppl. Fig. 1A-B). These results suggest that acacetin has the potential to suppress tumor-induced angiogenesis and thus could be an angiopreventive agent in cancer prevention and control.

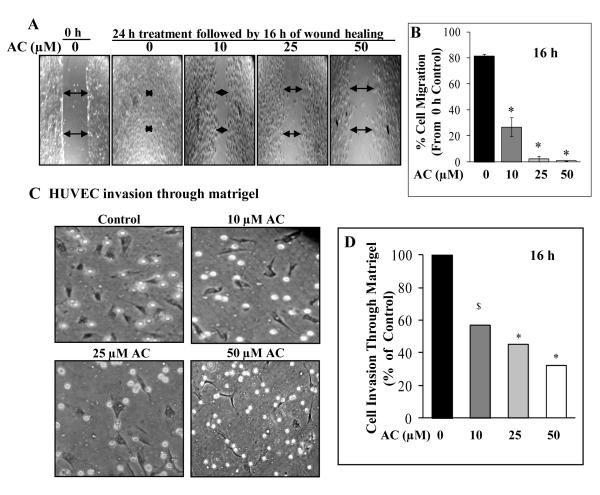

Acacetin suppresses HUVEC migration and invasion

Endothelial cell migration and invasion events are very critical during angiogenesis process. During tumor angiogenesis, endothelial cells proliferate, degrade and invade the surrounding basement membrane and migrate into the stroma. Finally, they differentiate and organize themselves in to new blood capillaries which are crucial for tumor growth (28). Since acacetin suppressed HUVEC capillary-tube formation, we next examined its effects on HUVEC migration and invasion processes (Fig. 3A-C). Acacetin (10, 25 and 50 μM) treatment for 24 h in regular growth condition followed by16 h migration in serum-free condition suppressed HUVEC migration by 67, 97 and ~100% (p<0.001), respectively, compared to control (Fig. 3A-B). Similarly, acacetin (10, 25 and 50 μM) treatment suppressed HUVEC matrigel invasion by 43, 55 and 68% (p<0.05-0.001), respectively (Fig. 3C-D). These observations suggest that acacetin has the potential to suppress angiogenesis via inhibiting endothelial cell invasion and migration.

Figure 3.

Effect of acacetin on migration and invasion potential of HUVEC. A: Representative images depicting cell migration by HUVEC after 16 h following 24 h treatment with or without AC in the wound healing assay. Wound closure was recorded at 0 and 16 h after injury using an inverted microscope equipped with a digital camera as mentioned in Methods. B: Bar diagram showing the effect of 24 h AC treatment on wound closure/migration potential of HUVEC after 16 h post injury. Five independent areas in each wound were measured. Data are shown as percent cell migration compared to 0 h control at the time of injury. C: Representative images and its graphical representation depicting the effect of AC (0, 10, 25 and 50 μM) on HUVEC invasion/migration in matrigel-coated Boyden chambers after 16 h treatment. Cells were allowed to invade and migrate for 16 h and the invaded/migrated cells at the bottom of the membrane were fixed, stained and counted at 200x magnification, and photographed. D: Five independent areas were scored in each sample and data are shown as percent cell migration compared to control. $, p<0.005; *, p<0.001 versus DMSO control.

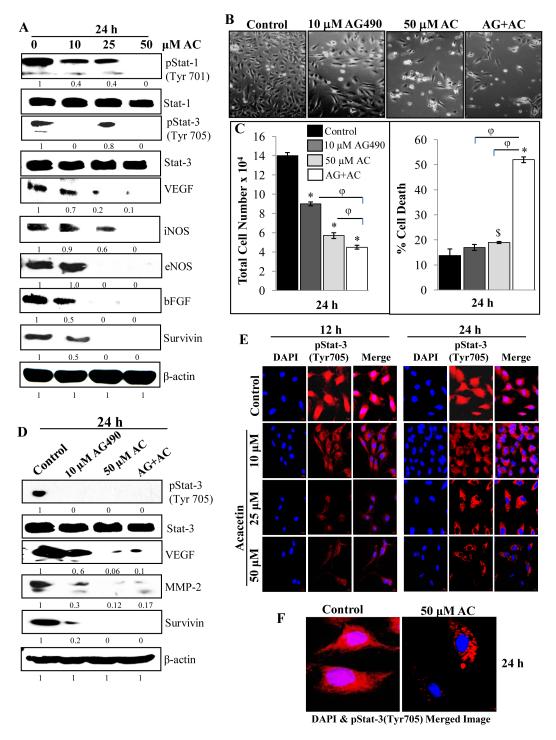

Acacetin inhibits Stat signaling and expression of angiogenic factors in HUVEC

Stats are important regulators of angiogenesis and can induce the expression of VEGF, iNOS and survivin (29-31). In the present study, we observed that acacetin strongly inhibits activation of Stat-1 and -3 leading to concomitant down-regulation of down-stream targets including VEGF, iNOS, eNOS, bFGF and survivin. Acacetin (10-50 μM) treatment for 24 h under regular growth condition inhibited phosphorylation of both Stat-1(Tyr701) and Stat-3(Tyr705), and dose-dependently decreased the expression level of their targets including VEGF, iNOS, eNOS, bFGF and survivin (Fig. 4A). Acacetin treatment for 24 h under regular growth conditions in the presence or absence of Janus kinase inhibitor AG490, that inhibits the phosphorylation and activation of Stat-3, suppressed HUVEC proliferation (p<0.001) and also induced cell death (p<0.05-0.001) with greater efficacy in combination treatment (Fig. 4B-C). The combination treatment showed significantly (p<0.001) higher effects from that of their individual treatment for both cell number and cell death, however, the decrease in total cell number is contributed mostly via enhancing cell death. Concomitantly, AG490, acacetin or their combination also inhibited Stat-3 (Tyr705) phosphorylation levels compared to the DMSO control (Fig. 4D). AG490 also decreased the protein levels of VEGF, MMP-2 and survivin, and this effect was further enhanced in combination with acacetin treatment (Fig. 4D). Overall, these observations suggest that one of the mechanisms by which acacetin could inhibit various angiogenic attributes in endothelial cells could be due to the inhibition of Stat signaling and associated with a decrease in VEGF, iNOS, eNOS and bFGF expression. The decrease in survival could be associated with the decrease in survivin level.

Figure 4.

Acacetin inhibits Stat signaling and expression of angiogenic factors in HUVEC. A: HUVEC were grown to 70% confluency and treated with the indicated concentrations of AC for 24 h. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific primary antibodies for pStat-1 (Tyr701); Stat-1; pStat-3 (Tyr705); Stat-3; VEGF, iNOS, eNOS, bFGF and survivin followed by detection with HRP-labeled appropriate secondary antibodies as mentioned in Methods. β-actin was probed after stripping the membrane as protein loading control. B-C: Representative pictures and quantitative data depicting the effect of AG490 (Janus kinase inhibitor) and AC in individual as well as combination treatments on HUVEC growth and death after 24 h of treatment in regular conditions. D: In similar treatments as in (C), whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific primary antibodies for pStat-3 (Tyr705); Stat-3; VEGF, MMP-2 and survivin. Membranes were stripped and re-probed for beta-actin as loading control. E: Confocal depictions of the effects of AC on nuclear translocation of pStat-3. HUVEC were grown on coverslips for 24 h followed by treatments with the indicated doses of AC for indicated time points in regular growth conditions. At the end of the treatments, cells were processed for confocal assay as mentioned in Methods using specific primary pStat-3 (Tyr705) antibody followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-secondary antibody. Slides were mounted and immediately viewed and photographed under LSM780 Laser Confocal Microscope F: A higher magnification image is shown for control and 50 μM AC for 24 h treatment. $, p<0.005; *, p<0.001 versus DMSO control; φ, p<0.001 versus AC or AG490 treatment.

Acacetin inhibits nuclear translocation of Stat-3 (Tyr705) in HUVEC

Stat-3, a transcription factor regulating the expression of VEGF and other pro-angiogenic genes, is activated by phosphorylation at critical residues like tyrosine 705. After this phosphorylation, it gets translocated in to the nucleus to carry out its transcriptional activities. Since, acacetin inhibited phosphorylation of Stat-3 (Tyr705); we examined whether it also inhibited its nuclear localization in HUVEC. Acacetin treatment under regular growth conditions at 10, 25 and 50 μM showed the reduced immunofluorescence for pStat-3 (Tyr705) in nucleus after 12 and 24 h compared to DMSO control (Fig. 4E-F). pStat-3 (Tyr705) levels were decreased in a dose-dependent manner compared to control, and it was virtually undetectable in the nucleus at 50 μM acacetin treatment for 24 h (Fig. 4F). These observations suggest that acacetin inhibits Stat-3 activation and its nuclear localization and hence could strongly suppress its transcriptional activity. Thus, Stat-3 signaling could be a potential target for acacetin in its angiopreventive efficacy.

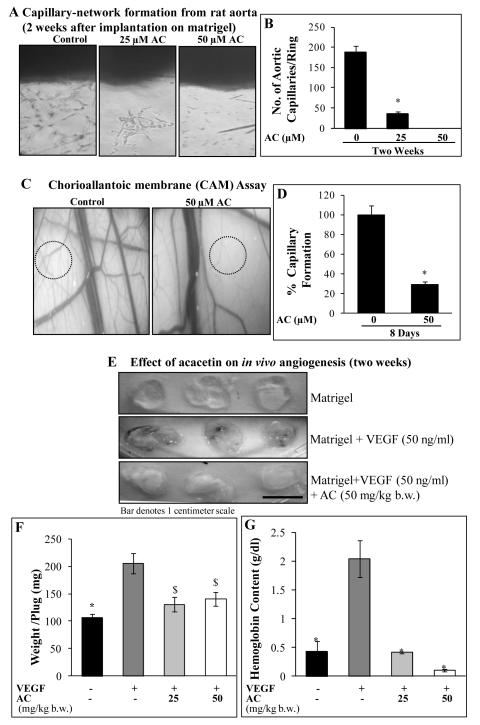

Acacetin suppresses ex vivo angiogenesis

Ex vivo models of angiogenesis allow examining the effects of various agents on angiogenesis in more relevant conditions where more cell types are involved in the process. Since we observed that acacetin strongly inhibits various attributes of angiogenesis in vitro, we next assessed its effects on ex vivo angiogenesis in rat aortic ring and CAM angiogenesis models. Under regular growth conditions, acacetin strongly suppressed capillary sprouting as well as networking from rat aortic rings as well as developing egg CAMs as depicted in the representative pictures (Fig. 5A-C). Compared to DMSO control, 25 and 50 μM doses of acacetin inhibited angiogenesis from rat aortic rings by 81 and 100% (p<0.001), respectively, after two weeks of treatment (Fig. 5B). Similarly, acacetin inhibited both capillary sprouting and networking from larger vessels in developing CAMs by 71% at 50 μM dose (p<0.001) after 8 days of treatment under regular conditions (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that by strongly inhibiting angiogenesis in both rat aortic ring and CAM models, acacetin has the potential to suppress angiogenesis in more complex systems involving complex angiogenic events including endothelial cell proliferation, invasion, migration, differentiation and capillary organization, and also where involvement of other cell types occurs.

Figure 5.

Effects of acacetin on ex vivo and in vivo angiogenesis. A-B: Rat aortic ring sections were embedded in matrigel and cultured in complete EGM2-MV medium. After two days, AC (0, 25 and 50 μM) treatments were started and continued after every 48 h for 2 weeks. At the end, rings were photographed and vessels were scored by counting total number of vessels originating from the rings. A: Representative pictures depicting the effect of AC on rat aortic ring angiogenesis; and B: quantitative representation of the data as Mean ± SE of total number of aortic capillaries as a function of AC concentration. C-D: For CAM angiogenesis assay, fertilized chicken eggs were incubated and treated with AC every 48 h for 8 days as mentioned in Methods. Thereafter, individual CAMs were analyzed and photographed using digital camera with 10x zoom (C) and data were quantified by counting the nascent vessels between the major blood vessels and represented as Mean ± SE of total number of vessels in 5 independent areas on CAMs for each treatment (D). E-G: Acacetin suppresses VEGF-induced in vivo angiogenesis. Mice were randomly divided into four groups (n=5/group); and subcutaneously received matrigel only (Control), or matrigel + VEGF (50 ng/ml) or matrigel + VEGF (50 ng/ml) + AC (25 or 50 mg/kg body wt). After 14 days, mice were sacrificed and plugs were retrieved, photographed, weighed and hemoglobin content measured as described in Methods. E: Photographs of representative matrigel plugs, F: Weight of matrigel plugs (mg/plug); and G: hemoglobin content (g/dl) are shown. Body weight and diet/water consumption did not change among groups (data not shown). $, p<0.005; *, p<0.001 versus DMSO control or VEGF control.

Acacetin inhibits angiogenesis in vivo

Since, acacetin showed strong anti-angiogenic activities by inhibiting angiogenesis both in vitro as well as ex vivo; we also examined its in vivo anti-angiogenic efficacy employing matrigel plug assay in Swiss albino mice. Briefly, matrigel was thawed and kept on ice and subcutaneously implanted in the right flanks of mice with or without VEGF (50 ng/ml) and acacetin (25 or 50 mg/kg body weight) for two weeks. There was no considerable change in diet or water consumption by mice during the experiment (data not shown). Since VEGF attracts blood capillary/vessel growth into the matrigel plugs when implanted in mice, both plug-weight as well as hemoglobin (Hb) content of plugs increase with VEGF treatment compared to control group. Plug weight (in mg) and Hb content (in g/dl) were measured to quantitate angiogenesis. We observed that acacetin strongly suppressed these VEGF-induced angiogenic parameters after two weeks of treatment (Fig. 5E). Acacetin treatment decreased plug weight by 36 and 32% (p<0.05) and Hb content of plugs by 80 and 95% (p<0.001) compared to VEGF only control, respectively, at 25 and 50 mg/kg body weight doses (Fig. 5F-G). These results suggest that acacetin possesses strong in vivo anti-angiogenic efficacy.

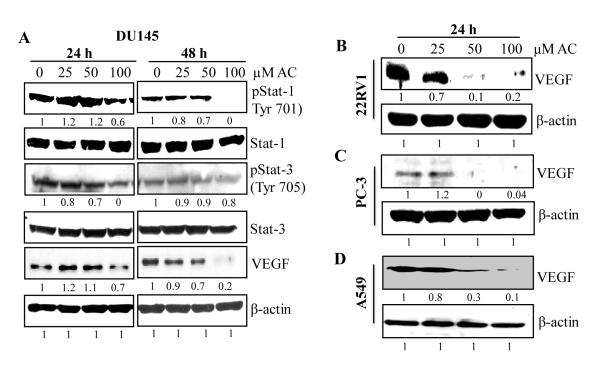

Acacetin inhibits activation of Stat and expression of VEGF in cancer cells

Cancer cells secrete various angiogenic factors which change behavior of neighboring endothelial cells and promote growth of blood vessels/capillaries to supply tumors with nutrients, support their gaseous exchange and metabolic waste removal and hence, promote tumor growth and progression (11,33,34). Expression of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF in solid tumors like prostate and lung cancers is very high owing to the activation of various signaling pathway including Stat signaling (35-37). These factors play important role in vessel remodeling and tumor angiogenesis. Therefore, we examined whether acacetin could suppress Stat activation and expression of VEGF in different human prostate (DU145, PC-3 and 22Rv1) and lung (A549) cancer cell lines. Acacetin suppressed phosphorylation of Stat-1 (Tyr701) and Stat-3 (Tyr705) in prostate carcinoma DU145 cells, and strongly downregulated VEGF protein expression in prostate and lung cancer cells (Fig. 6A-D). Therefore, acacetin has potential to suppress Stat-VEGF axis in tumors as observed in endothelial cells.

Figure 6.

Effects of acacetin on activation and/or expression of various proangiogenic factors in human cancer cells. A-C: Human prostate carcinoma DU145, 22Rv1 and PC-3 and D: human lung carcinoma A549 cells were grown to 70% confluency and treated with the indicated concentrations of AC for 24 and/or 48 h in regular growth conditions. Subsequently, whole cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting using specific primary antibodies for pStat-1 (Tyr701); Stat-1; pStat-3 (Tyr705); Stat-3 and VEGF proteins followed by detection with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies using enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. β-actin was probed after stripping the membranes as protein loading control.

Discussion

Solid tumors grow up to ~2-3 mm diameter size and stop growing further entering phase of tumor dormancy which is broken down by the onset of angiogenesis (2,3). Angiogenesis plays a vital role in tumor growth and their metastatic progression, and is a potential target in cancer prevention and control (1,11,38) Angioprevention with phytochemicals, shown to suppress tumor growth and metastatic progression in animal models, is considered as an effective strategy in prevention, control and treatment of cancer (1,11). Herein, we evaluated the angiopreventive efficacy and associated mechanisms of acacetin, that has been shown to inhibit the growth of cancer cells (19-25), in in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo models of angiogenesis. The major findings are that acacetin inhibits various attributes of angiogenesis including (a) growth and survival, (b) invasion, (c) migration and (d) capillary tube formation by HUVEC under various experimental conditions; ex vivo angiogenesis in (e) rat aortic ring and (f) CAM models; (g) in vivo angiogenesis in matrigel plugs implanted in Swiss albino mice; and (h) these effects could be due to acacetin-mediated suppression of Stat-VEGF axis in endothelial as well as cancer cells. These findings suggest that antiangiogenic activity of acacetin could be a major contributor to its overall antitumor effects.

Angiogenesis is a multistep process involving endothelial cell growth and survival, invasion, migration and capillary-tube formation, organization and maturation into blood vessels, and VEGF plays a very important role during this process. Any agent inhibiting one or more of the above processes can impair angiogenesis and hence, halt tumor growth and metastasis (11). In present study, acacetin strongly suppressed HUVEC proliferation and survival in regular growth conditions along with the induction of significant cell death. It also strongly inhibited HUVEC growth and survival, and induced potent cell death under hypoxic conditions (data not shown). Furthermore, acacetin strongly inhibited VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation and survival. These results suggest that acacetin has the potential to suppress angiogenesis in response to angiogenic stimuli.

During tumor angiogenesis, the formation of new blood capillaries is an important event and its inhibition halts vessel recruitment to tumors. We observed that acacetin robustly (up to 98%) inhibited HUVEC capillary-tube formation in a dose- and time-dependent manner under regular as well as VEGF-stimulated conditions. Since, aggressive or established solid tumors are angiogenic and harbor blood capillaries supplying them nutrients and other factors; therefore, disruption of established vessel/capillary growth in tumors could be an important strategy in controlling the growth of solid tumors. In this regard, acacetin strongly (~91%) inhibited the growth of pre-formed or rudimentary capillary network on matrigel. VEGF stimulates blood vessel formation both in vitro and in vivo (35,36,39,40). Acacetin also suppressed VEGF-induced capillary-tube formation by HUVEC. Since, tumor cells secrete various pro-angiogenic factors which attract and stimulate blood capillary growth towards tumor mass leading to tumor growth and progression; therefore, targeting tumor-induced angiogenesis would be a desired strategy in angioprevention of cancer. We observed that acacetin strongly inhibited A549 TCM-induced capillary formation by HUVEC. These findings suggest that acacetin can abrogate angiogenesis and hence, tumor growth by suppressing both de novo blood capillary formation as well as growth of pre-formed rudimentary capillary networks.

Endothelial cell migration and invasion are essential and rate limiting events during capillary growth and organization; and hence, inhibition of such events is a promising angiopreventive strategy. Acacetin potently inhibited HUVEC motility in wound healing assay which was almost completely inhibited at higher dose. This effect was further examined using matrigel invasion and migration that showed a similar trend in inhibiting these biological events. Altogether, acacetin showing inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation, invasion, migration and capillary-tube formation emphasize its importance in targeting various key attributes of angiogenesis process.

VEGF is a prominent pro-angiogenic factor that stimulates angiogenesis and has been identified as a potential anti-angiogenic target (39,40). Stat signaling that regulates the expression of angiogenic molecules is implicated in tumor angiogenesis as well as tumor growth and progression (30,31,41) Inhibiting Stat activation by suppressing its phosphorylations at key tyrosine residues inhibits tumor angiogenesis (21,30,37,41,42,44). Phosphorylations at Tyr 701 in Stat-1, and Tyr 705 in Stat-3 leading to their transcriptional activities are important events in activating the expression of VEGF, iNOS, eNOS, survivin and MMP-2 (42,43). We found that acacetin inhibits these Tyr phosphorylations of Stat-1 and Stat-3 with concomitant suppression of expression of the targets. bFGF, another important molecule involved in promoting angiogenesis, was also down-regulated by acacetin in endothelial cells. Stat-3 activation and its subsequent translocation in to nucleus are important for its transcriptional activity. In immunofluorescence study, acacetin decreased Stat-3 (Tyr 705) phosphorylation as well as its nuclear translocation. Therefore, acacetin-mediated down-regulation of VEGF as well as survivin, MMP-2, bFGF, iNOS and eNOS in HUVEC could, in part, occur through inhibition of Stat signaling.

To test whether acacetin could inhibit angiogenesis in relevant ex vivo models where more complex angiogenic system works involving more cell types, we employed well accepted aortic ring and CAM angiogenesis assays. Aortic rings cultured on matrigel give rise to microvascular networks composed of branched endothelial channels; and it recapitulates more accurately the environment in which angiogenesis takes place than those with isolated endothelial cells. Acacetin showed strong to almost complete inhibition of capillary sprouting from the rat aortic ring explants. Chorioallantoic membrane is a specialized vascular tissue of avian embryo and used to test pro- or anti-angiogenic activities of various agents. Blood vessel formation in CAMs mimics closely in vivo angiogenesis as they follow same pattern involving many cell types including pericytes. Acacetin inhibited vessel growth and networking from the established blood vessels in CAMs. These findings suggest that acacetin may also inhibit in vivo angiogenesis which was examined employing in vivo model of mouse matrigel plug assay. Acacetin strongly inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenic parameters including plug-weight and Hb content of plugs. These results together advocate that acacetin has the potential to suppress ex vivo as well as in vivo angiogenesis.

Solid tumors express and secrete diffusible angiogenic factors, like VEGF, that change the behavior of neighboring blood vessels and encourage the growth of new capillaries towards tumor mass (11,45,46). It is known that Stat activation regulates VEGF expression in cancer cells in response to multiple oncogenic growth signaling (37,44). Therefore, suppression of Stat signaling and angiogenic factors in tumors can inhibit tumor angiogenesis and hence tumor growth. To examine such possibility, we employed human prostate carcinoma DU145, PC-3 and 22Rv1 cells. Acacetin decreased the phosphorylation of Stat-1 (Tyr 701) and Stat-3 (Tyr 705) in DU145 cells concomitant with decrease in VEGF protein level. Acacetin also decreased the VEGF protein level in PC-3, 22Rv1 and lung carcinoma A549 cells. Thus acacetin has capability to target Stat-VEGF axis in cancers cells to suppress tumor angiogenesis.

Overall, the present study shows that acacetin is a potent and promising small molecule anti-angiogenic agent which inhibits various attributes of angiogenesis including HUVEC growth, invasion and migration, and strongly suppresses in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo angiogenesis. The anti-angiogenic effects of acacetin could be mediated via inhibition of Stat-VEGF axis in endothelial as well as cancer cells. Further studies employing animal tumor models are warranted to support clinical usefulness of acacetin in cancer prevention and control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from CSIR (37/1391-09/EMR-II) India, UGC Resource Networking fund, DST-PURSE, India, Capacity Build-up fund from JNU, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar and NCI R01 CA102514. T.A. Bhat and D. Nambiar are supported by fellowships from CSIR, India. Assistance for Confocal Microscopy by Vijay Mohan, Central University of Gujarat is acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- AC

acacetin

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- PCa

prostate cancer

- Stat

signal transducers and activators of transcription

- CAM

chorioallantoic membrane

- FBS

fetal bovine serum albumin

- Hb

hemoglobin

References

- 1.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naumov GN, Akslen LA, Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in human tumor dormancy: animal models of the angiogenic switch. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(16):1779–87. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naumov GN, Folkman J, Straume O. Tumor dormancy due to failure of angiogenesis: role of the microenvironment. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(1):51–60. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halvorsen O, Haukaas S, Hoisaeter P, Akslen L. Independent prognostic importance of microvesel density in clinically localized prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3791–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gettman MT, Pacelli A, Slezak J, Bergstralh EJ, Blute M, Zincke H, Bostwick DG. Role of microvessel density in predicting recurrence in pathologic Stage T3 prostatic adenocarcinoma. Urology. 1999;54:479–85. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983–85. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweigerer L. Antiangiogenesis as a novel therapeutic concept in pediatric oncology. J Mol Med (Berl) 1995;73(10):497–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00198901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nat Med. 2000;407:249–57. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6(3):389–95. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruoslahti E. Specialization of tumour vasculature. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat TA, Singh RP. Tumor angiogenesis-a potential target in cancer chemoprevention. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(4):1334–45. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhat TA, Moon JS, Lee S, Yim D, Singh RP. Inhibition of angiogenic attributes by decursin in endothelial cells and ex vivo rat aortic ring angiogenesis model. Indian J Exp Biol. 2011;49(11):848–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samant RS, Shevde LA. Recent advances in anti-angiogenic therapy of cancer. Oncotarget. 2011;2(3):122–34. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardin J, Cheng I, Witte JS. Impact of consumption of vegetable, fruit, grain, and high glycemic index foods on aggressive prostate cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(6):860–72. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.582224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen RJ, Robinson DP, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Bamlet WR, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption is inversely associated with having pancreatic cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(12):1613–25. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9838-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakai K, Matsuo K, Nagata C, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, Tsuji I, Sasazuki S, Shimazu T, Sawada N, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Lung cancer risk and consumption of vegetables and fruit: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiological evidence from Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41(5):693–08. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu L, Cheung KL, Khor TO, Chen C, Kong AN. Phytochemicals: cancer chemoprevention and suppression of tumor onset and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(3):483–502. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanadaswami C, Lee LT, Lee PP, Jwang JJ, Ke FC, Huang YT, Lee MT. The antitumor activities of flavonoids. In vivo. 2005;19(5):895–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Liu CF, Lin CC. Acacetin-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Cancer Lett. 2004;212(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Lin CC. Acacetin inhibits the proliferation of Hep G2 by blocking cell cycle progression and inducing apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67(5):823–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh RP, Agrawal P, Yim D, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Acacetin inhibits cell growth and cell cycle progression, and induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells: structure-activity relationship with linarin and linarin acetate. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(4):845–54. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim HY, Park JH, Paik HD, Nah SY, Kim DS, Han YS. Acacetin-induced apoptosis of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells involves caspase cascade, mitochondria-mediated death signaling and SAPK/JNK1/2-c-Jun activation. Mol Cells. 2007;24(1):95–04. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen KH, Hung SH, Yin LT, Huang CS, Chao CH, Liu CL, Shih YW. Acacetin, a flavonoid, inhibits the invasion and migration of human prostate cancer DU145 cells via inactivation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;333:279–91. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien ST, Lin SS, Wang CK, Lee YB, Chen KS, Fong Y, Shih YW. Acacetin inhibits the invasion and migration of human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells by suppressing the p38α MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;350:135–48. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe K, Kanno S, Tomizawa A, Yomogida S, Ishikawa M. Acacetin induces apoptosis in human T cell leukemia Jurkat cells via activation of a caspase cascade. Oncol Rep. 2012;27(1):204–9. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu LZ, Jing Y, Jiang LL, Jiang XE, Jiang Y, Rojanasakul Y, Jiang BH. Acacetin inhibits VEGF expression, tumor angiogenesis and growth through AKT/HIF-1α pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413(2):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhat TA, Nambiar D, Pal A, Agarwal R, Singh RP. Fisetin inhibits various attributes of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo-implications for angioprevention. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(2):385–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blood CH, Zetter BR. Tumor interactions with the vasculature: angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1032(1):89–118. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(90)90014-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley AC, Thomas D, Best J, Jenkins A. A VEGF/JAK2/STAT5 axis may partially mediate endothelial cell tolerance to hypoxia. Biochem J. 2005;390(Pt 2):427–36. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z, Han ZC. STAT3: a critical transcription activator in angiogenesis. Med Res Rev. 2008;28(2):185–200. doi: 10.1002/med.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niu G, Wright KL, Huang M, Song L, Haura E, et al. Constitutive Stat3 activity up-regulates VEGF expression and tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21(13):2000–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slomiany MG, Rosenzweig SA. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent and -independent regulation of insulin-like growth factor-1-stimulated vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:666–75. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veikkola T, Karkkainen M, Claesson-Welsh L, Alitalo K. Regulation of angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coppé JP, Kauser K, Campisi J, Beauséjour CM. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. JBC. 2006;281(40):29568–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buettner R, Mora LB, Jove R. Activated STAT signaling in human tumors provides novel molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(4):945–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tosetti F, Ferrari N, De Flora S, Albini A. Angioprevention: angiogenesis is a common and key target for cancer chemopreventive agents. FASEB J. 2002;16(1):2–14. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0300rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, Armanini M, Gillett N, Phillips HS, Ferrara N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor induced angiogenesis suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Nature. 1993;362:841–44. doi: 10.1038/362841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science. 1989;246:1306–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer - new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Can. 2004;4:97–05. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE., Jr Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82(2):241–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Qiao Di, Meyer K, Friedl A. Signal transducers and activators of transcription mediate fibroblast growth factor-induced vascular endothelial morphogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1668–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Q, Briggs J, Park S, Niu G, Kortylewski M, Zhang S, Gritsko T, et al. Targeting Stat3 blocks both HIF-1 and VEGF expression induced by multiple oncogenic growth signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:5552–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon MS, Mendelson DS, Kato G. Tumor angiogenesis and novel antiangiogenic strategies. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1777–87. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLesky SW, Tobias CA, Vezza PR, Filie AC, Kern FG, Hanfelt J. Tumor growth of FGF or VEGF transfected MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells correlates with density of specific microvessel independent of the transfected angiogenic factor. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(6):1993–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65713-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.