Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the walking speed maintained during a 1 km treadmill test at moderate intensity predicts survival in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Design

Population-based prospective study.

Setting

Outpatient secondary prevention programme in Ferrara, Italy.

Participants

1255 male stable cardiac patients, aged 25–85 years at baseline.

Main outcome measures

Walking speed maintained during a 1 km treadmill test, measured at baseline and mortality over a median follow-up of 8.2 years.

Results

Among 1255 patients, 141 died, for an average annual mortality of 1.4%. Of the variables considered, the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality was walking speed (95% CI 0.45 to 0.75, p<0.0001). Based on the average speed maintained during the test, participants were subdivided into quartiles and mortality risk adjusted for confounders was calculated. Compared to the slowest quartile (average walking speed 3.4 km/h), the relative mortality risk decreased for the second, third and fourth quartiles (average walking speed 5.5 km/h), with HRs of 0.73 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.18); 0.54 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.95) and 0.20 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.56), respectively (p for trend <0.0001). Receiver operating curve analysis showed an area under the curve of 0.71 (p<0.0001) and the highest Youden index (0.35) for a walking speed of 4.0 km/h.

Conclusions

The average speed maintained during a 1 km treadmill walking test is inversely related to survival in patients with cardiovascular disease and is a simple and useful tool for stratifying risk in patients undergoing secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation programmes.

Keywords: walking speed , survival, cardiac patients

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The walking test used in this study measures cardiovascular function. The test is submaximal, easy to perform and allows the concurrent measurement of physiological data.

The study included male participants only, and the results may not be generalised to women.

Participants not able to walk for 1 km were excluded from the study.

Introduction

In patients with cardiovascular disease, peak oxygen consumption is utilised for assessing disease severity and for quantifying the effectiveness of secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation programmes.1 2 Moreover, it is a strong independent predictor of risk of death and for estimating risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes.3

Peak oxygen consumption is commonly determined by maximal exercise testing, but it can be difficult to carry out in some cardiac patients. For this reason, walking tests at a submaximal exercise intensity have been developed for quantifying functional capabilities of patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary disease,4 including time-based5 6 and distance-based protocols7–9 involving walking on the ground, treadmill or along a corridor.10–13 Short walking tests have also been employed, but they generally do not adequately quantify aerobic fitness,14 and the optimal duration or length for these submaximal protocols has been debated.15

Walking tests have been used to assess exercise capacity16–19 and to investigate outcomes in many rehabilitation programmes.20 Walking speed has been considered a ‘vital sign’ and a surrogate of physiological function in several cohort studies among patients with cardiovascular disease.19 Walking speed is a commonly used objective measure of functional capabilities among older patients and has been demonstrated to be a strong predictor of survival.21 22 For example, a threefold higher risk of mortality in the lowest quartile of walking speed compared to the highest quartile was reported in a recent meta-analysis.21–24 However, less is known about the prognostic relevance of walking performance in younger individuals with cardiovascular disease, particularly for community-based programmes.25

We recently developed a moderate-intensity, self-paced 1 km walking test for the indirect estimation of peak oxygen consumption in patients with cardiovascular disease across a broad age range.26 In the current study, we addressed the association between average walking speed maintained during this 1 km test and survival in a cohort of patients with stable cardiovascular disease. The average walking speed maintained during the 1 km test among 1255 patients was determined, and all-cause mortality over 10 years of follow-up was quantified.

Methods

The study population consisted of 1442 men, with stable cardiovascular disease, aged 25–85 years, referred by their physician to the Department of Rehabilitative Medicine of the University of Ferrara, Italy, for participation in an exercise-based secondary prevention programme, between 1997 and 2012.

The programme was guided by a cardiologist and a sports medicine doctor. A comprehensive clinical evaluation, including personal medical history, risk factor and medications was carried out. Left ventricular ejection fraction was derived from previous echocardiographic evaluations. Standard blood chemistry analyses previously performed were registered. Weight and height were measured and used to calculate body mass index.

Participants with heart failure classified as New York Heart Association class II or higher, and those who had conditions that interfered with walking ability such as neurological, musculoskeletal or peripheral vascular conditions were not included in the study.

One hundred and twenty-seven women, aged 60 (10), with an average walking speed of 3.9 (0.7) km/h, were considered. During the follow-up period, 9 (7%) of these excluded participants died. Because of the small number of woman and events a stratified analysis according to gender was not feasible.

Walking speed determination

The average walking speed was determined for each participant at the time of their baseline examination using the 1 km treadmill walking test previously described and developed in 178 participants belonging to the same population of the current study.26 Briefly, the test was carried out as follows: the participants were instructed to select a pace that they could maintain for 10–20 min at a moderate perceived exercise intensity using the Borg 6–20 scale.27 Participants began the test walking on the level at 2 km/h, with subsequent increases of 0.3 km/h every 30 s up to a walking speed corresponding to a perceived exertion of 11–13 on the Borg scale. The test was then started and the rate of perceived exertion acquired every 2 min. Walking speed was adjusted to maintain the selected moderate perceived intensity. Heart rate was monitored continuously during the test using a Polar Accurex Plus heart rate monitor (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland). Blood pressure was monitored before and immediately after the test. The time to complete 1 km was recorded and average walking speed calculated accordingly.

Mortality assessment

Participants were followed for all-cause mortality from the date of their baseline examination for up to 10 years. Participants were flagged by the regional Health Service Registry of the Emilia-Romagna region, which provided the date of death where applicable, or by contacting relatives and the personal physician to determine the vital status.

Covariates

The covariates considered as potential confounders were: average walking speed, age, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, current smoking, hypertension, family history, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum triglycerides, serum creatinine, personal medical history (coronary artery bypass graft, myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, valvular replacement and medical therapy for stable angina) and use of ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, aspirin, β-blockers, calcium antagonists, diuretics, statins and number of medications.

Statistical analysis

All-cause mortality was used as the end point for survival analysis. Differences in survival across quartiles during the follow-up period were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated across quartiles using Cox proportional hazard models. Individuals in the quartile with the lowest average walking speed were considered the reference group. The models were adjusted for confounders significantly related to death. The assumption of proportionality of all variables introduced in the models was assessed through the analysis of Schoenfeld residuals. The proportional hazards assumption held for all models. To assess the discriminatory accuracy of the average walking speed in estimating survival, receiver operating characteristics curves were constructed and the corresponding areas under the curve were calculated. The optimal cut-off point was calculated using the Youden index (sensitivity+specificity − 1).28 The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc V.11.4 software, Mariakerke, Belgium.

Results

Of the 1442 participants who were initially included in the study, 187 (13%) were excluded due to the inability to complete the 1 km test. These participants were significantly older (70 vs 61 years, p<0.0001), had a higher body mass index (28.4 vs 27.6, p<0.01), a higher prevalence of hypertension (68% vs 57%, p=0.002), higher serum creatinine (1.7 vs 1.1 mg/dL, p<0.001) and a lower ventricular ejection fraction (53% vs 56%, p=0.001). In addition, those excluded had a lower use of statins (35% vs 53%) and β-blockers (43% vs 59%) and a higher use of diuretics (44% vs 18%). Seventy-one of these participants died during the 10 years of follow-up.

The 1 km walking test was completed by the remaining 1255 participants at an average speed of 4.3 (0.8) km/h. The median follow-up period was 8.2 years during which a total of 141 deaths from any cause occurred, yielding an average annual mortality of 1.4%.

The baseline variables of the study population, stratified in quartiles of average walking speed, are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 1255 participants by quartile of average walking speed

| Variable | All Participants (n=1255) | I Quartile (n=316) | II Quartile (n=313) | III Quartile (n=300) | IV Quartile (=326) | p for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWS | ||||||

| (km/h) | 4.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.1) | 4.6 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| (m/s) | 1.19 (0.22) | 0.94 (0.08) | 1.13 (0.02) | 1.27 (0.05) | 1.53 (0.14) | |

| Deaths (n) | 141 | 68 | 43 | 18 | 12 | <0.001 |

| Age (year) | 61 (10) | 65 (9) | 63 (9) | 59 (9) | 57 (9) | <0.001 |

| Risk factor | ||||||

| BMI | 27.6 (3.4) | 28.3 (3.7) | 27.6 (3.3) | 27.7 (3.2) | 27.0 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 56 (10) | 53 (11) | 56 (9) | 57 (11) | 58 (10) | 0.002 |

| Family history (%) | 53.7 | 48.4 | 51.7 | 54.3 | 60.7 | 0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 107 (27) | 110 (28) | 110 (28) | 106 (29) | 105 (28) | 0.03 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 194 (42) | 195 (47) | 199 (43) | 194 (41) | 188 (39) | 0.04 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49 (14) | 50 (16) | 49 (13) | 47 (14) | 50 (13) | 0.55 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dL) | 139 (80) | 147 (97) | 138 (71) | 143 (80) | 129 (67) | 0.046 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||||

| CABG | 49.4 | 63.3 | 52.0 | 46.3 | 36.2 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 28.1 | 22.2 | 29.1 | 31.3 | 30.0 | 0.02 |

| PTCA | 8.7 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 15.3 | 0.001 |

| Valvular replacement | 8.9 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 10.4 | 0.4 |

| Other | 4.4 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 5 | 7.4 | 0.001 |

| Medications (%) | ||||||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 53.3 | 57.3 | 54.0 | 50.0 | 68.9 | 0.09 |

| Aspirin | 74.6 | 75.9 | 72.8 | 74.3 | 75.1 | 0.9 |

| β-Blocker | 59.4 | 57.9 | 63.6 | 60.0 | 55.8 | 0.4 |

| Calcium antagonist | 12.9 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 11.7 | 0.6 |

| Diuretic | 18.1 | 26.6 | 20.4 | 13.7 | 10.4 | <0.001 |

| Statin | 52.9 | 50.3 | 49.2 | 52.0 | 60.1 | 0.01 |

| Number of medications | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.004 |

Data are presented as mean (SD).

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AWS, average walking speed; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricular; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, stenting or both.

Clinical and exercise-test predictors of mortality from the Cox proportional hazards model are presented in table 2. After adjustment for age, the best predictor of an increased risk of death from any cause was average walking speed, followed by smoking status and fasting glucose.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted risk of death according to clinical variables

| Variable | HR | p Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.94 to 1.04 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.99 | 0.47 | 0.98 to 1.01 |

| Risk factor | |||

| Current smoking | 2.24 | 0.02 | 1.12 to 4.47 |

| Hypertension | 1.22 | 0.25 | 0.87 to 1.72 |

| Family history | 1.03 | 0.85 | 0.74 to 1.44 |

| Fasting glucose | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.99 to 1.01 |

| Total cholesterol | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.99 to 1.01 |

| Serum triglycerides | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.67 | 0.13 | 0.87 to 3.19 |

| Medical history | |||

| CABG | 1.10 | 0.57 | 0.78 to 1.58 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.74 to 1.63 |

| PTCA | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.34 to 1.76 |

| Valvular replacement | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.34 to 1.40 |

| Other | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.19 to 3.12 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 0.88 | 0.47 | 0.64 to 1.23 |

| Aspirin | 1.40 | 0.1 | 0.93 to 2.1 |

| β-blocker | 1.04 | 0.8 | 0.74 to 1.44 |

| Calcium antagonist | 0.80 | 0.4 | 0.48 to 1.34 |

| Diuretic | 1.30 | 0.17 | 0.89 to 1.91 |

| Statin | 0.97 | 0.9 | 0.70 to 1.35 |

| Number of medications | 1.08 | 0.15 | 0.97 to 1.19 |

| AWS | 0.58 | <0.0001 | 0.45 to 0.75 |

Data are from the Cox proportional-hazards model.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AWS, average walking speed; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricular; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, stenting or both.

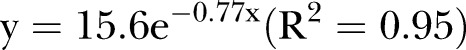

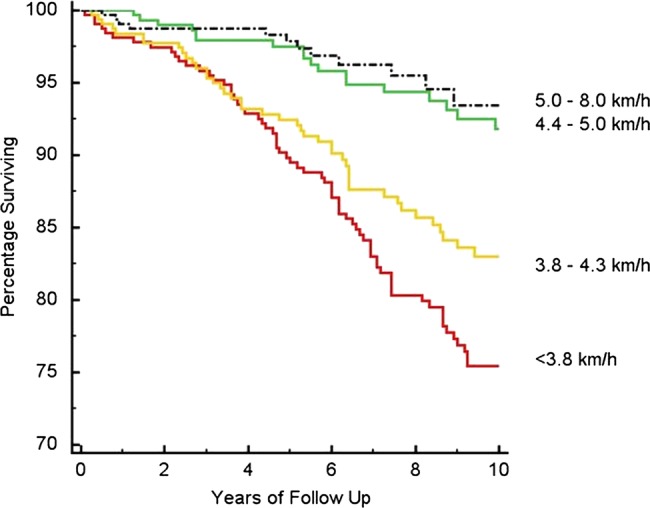

On the basis of the average walking speed, the participants were subdivided into quartiles. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the quartiles are presented in figure 1. Participants in the first quartile (average walking speed 3.4 km/h) had a marked reduction in survival compared to participants in the fourth quartile (average walking speed 5.5 km/h). Comparison between quartiles revealed significant differences in age, left ventricular ejection fraction, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, family history, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, serum triglycerides and creatinine, medical history, number of medication, diuretics and statins use. The relative risk of death from any cause across quartiles adjusted for these confounders is presented in table 3. An 80% reduction in risk of death was observed in the quartile with highest compared to the quartiles with slower average walking speeds. The reduction in risk was significant in third and fourth quartiles versus first quartile. The relationship between relative risk of death and average walking speed among the quartiles, after adjusting for confounders, fit the exponential equation (figure 2)

|

Figure 1.

Survival curves of the quartiles stratified according to average walking speed.

Table 3.

Full-adjusted relative risk of death from any cause according to quartiles of average walking speed

| AWS quartile | AWS (km/h) | AWS (m/s) | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 3.4 (0.3) | 0.94 (0.08) | 1.00 | – | – |

| II | 4.1 (0.1) | 1.13 (0.02) | 0.73 | 0.46 to 1.18 | 0.2 |

| III | 4.6 (0.2) | 1.27 (0.05) | 0.54 | 0.31 to 0.95 | 0.003 |

| IV | 5.5 (0.5) | 1.53 (0.14) | 0.20 | 0.07 to 0.56 | 0.003 |

Data are presented as mean (SD).

AWS, average walking speed.

Figure 2.

The exponential relationship between quartiles average walking speed and relative risk of death.

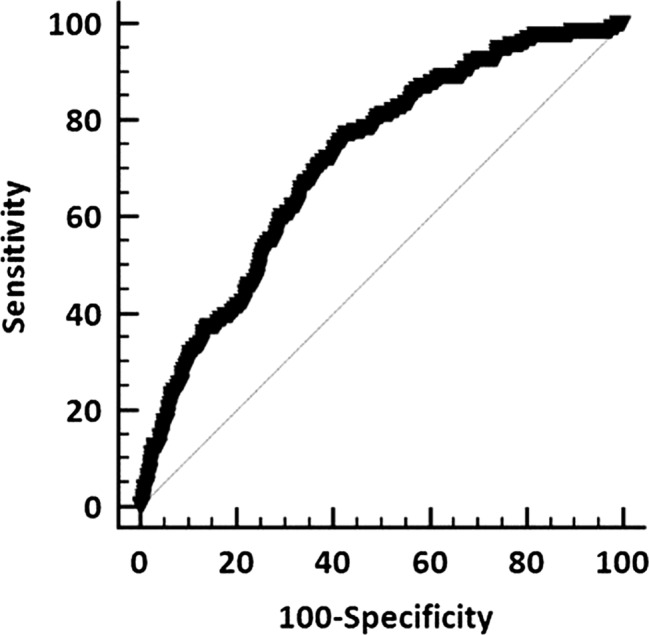

The strength of the average walking speed in the prediction of all-cause mortality is shown in figure 3 (area under the curve 0.71, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.74; p<0.0001). The highest Youden index (0.35) was observed at a walking speed of 4 km/h, corresponding to a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 65%.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for estimating the risk of death from any cause by average walking speed (area under the curve 0.71, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.74; p<0.0001).

In order to evaluate if the relationship between average walking speed and mortality could be applied to different age groups, participants were divided into three age categories at baseline: <60 years (n=471, average walking speed 4.7 (0.8) km/h, 39 died), 60–70 years (n=434, average walking speed 4.4 (0.8) km/h, 76 died) and >70 years (n=184, average walking speed 3.9 (0.7) km/h, 62 died). The association between average walking speed and mortality risk remained significant. The highest Youden index for the three age groups considered was 0.35 at 4.6 km/h for the <60 group; 0.32 at 4 km/h for the 60–70 group and 0.31 at 3.6 km/h for the >70 group.

During the second year of follow-up the average walking speed of 960 participants was determined. Of the 835 participants who improved their walking speed (from 4.3 (0.8) to 5.0 (0.8) km/h) 91 died while of the 125 participants who did not improve (from 4.7 (0.9) to 4.4 (0.8) km/h) 21 died. Adjusting for age the HR of the participants in which walking speed improved relative to the participants in which walking speed did not improve was reduced to 0.51 (p=0.006).

Discussion

We observed an inverse association between average walking speed, estimated by a 1 km treadmill test carried out at a perceived exertion between 11–13 on the 6–20 Borg scale, and all-cause mortality in a cohort of 1255 patients with stable cardiovascular disease. Independent from traditional cardiovascular risk factors and clinical history, low average walking speed was associated with higher rates of mortality.

The prognostic power of average walking speed was underscored by dividing the sample into quartiles; a significant reduction in risk of death was observed among the quartiles with higher average walking speeds compared to those with lower walking speeds. Participants with the highest walking speed after adjusting for confounders exhibited an 80% overall reduction in mortality risk compared to those with the lowest walking speed. The trend for risk of death sharply increased with the decreased of average walking speed.

These results extend the message on the health benefits of walking to patients with stable cardiovascular disease and support the concept that healthcare professionals should encourage cardiac patients to initiate and maintain a physically active lifestyle consisting of moderate walking at any age. The walking speed-related health benefits are achieved regardless of age.

The ability of the 1 km walking test to predict mortality we observed is similar to that reported by Studenskiet al21 and by Stanaway et al22 documenting the association between walking speed (determined by the use a short walking test of 4–6 m) and survival in healthy older adults. These gait speed tests, although short, are regarded as measures of lower extremity function and markers of physiological reserve.19 The 1 km walking test we used has the advantage of estimating cardiorespiratory function, since we have previously shown that it can be used for the indirect evaluation of peak oxygen consumption.26 Other tests, such as the widely-used 6 min walk test, are considered measures of submaximal endurance and have been shown to have prognostic value; however, these tests are performed at near-maximal intensity.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The 1 km walking test we developed is performed on a treadmill and therefore allows the concurrent measurement of physiological data including the ECG and can be performed comfortably in a standard exercise laboratory.29 It should also be noted that while peak oxygen consumption is often considered the gold standard for cardiopulmonary function,2 it is strongly influenced by genotype (accounting for up to 50% of its variance).30 In contrast, walking ability closely reflects a patient's cardiovascular capabilities associated with the capacity to perform daily activities and is therefore relevant for participants in secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation programmes.2

We have observed that an improvement in walking speed during follow-up in a subset of 835 patients was associated with a significant further reduction of their mortality risk. Therefore, the 1 km treadmill walking test offers the advantage of measuring the effectiveness of the prescribed rehabilitation programmes.

This study has some limitations. First, our findings are applicable only to men. Although it has been demonstrated that exercise capacity is an independent predictor of mortality in women,21 exercise testing responses between men and women have been disputed. In fact, some authors shown to differ significantly31 while others failed to demonstrate such differences.32 Second, in our study women were 127, aged 60 (10), with an average walking speed during the test of 3.9 (0.7) km/h and nine of them died during the follow-up period. Thus, because of the small number of woman and events a stratified analysis according to gender was not feasible. Third, participants were excluded from the test if they were not able to walk for 1 km and the results therefore may not apply to patients with markedly low exercise capacity. Fourth, we did not consider social, behavioural or psychological factors that have been independently associated with reduced walking speed.33 Fifth, these results were obtained from patients with an interest in participating in a secondary prevention programme. Therefore, external validation of our findings is needed. Finally, the prognostic value of walking speed determined at baseline on mortality can be modified by intervening clinical and functional changes occurring during the follow-up.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Our findings suggest that a simple and easy-to-perform 1 km treadmill walking test at a moderate intensity is a useful tool for identifying mortality risk in patients with stable cardiovascular disease. In addition to its utility for stratifying risk, the test can also be used by health professionals involved in secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation programmes to assess the efficacy of exercise prescription and to quantify functional changes regardless of age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Franco Guerzoni and Dr Nicola Napoli for their invaluable work over the years in data collection, management and retrieval.

Footnotes

Contributors: LC, FC, GM and GG conceived and designed the study. EB, GC, FC and GG analysed the data, interpreted the results and cowrote the manuscript. FT and SV analysed the data. JM discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethical commission of the University of Ferrara, Italy (application number 22-13) and Emilia Romagna Health Service human research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs. 4th edn Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arena R, Myers J, Williams MA, et al. Assessment of functional capacity in clinical and research settings: AHA scientific statement. Circulation 2007;116:329–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, et al. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 2002;346:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, et al. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 2001;119:256–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knox AJ, Morrison JF, Muers MF. Reproducibility of walking test results in chronic obstructive airways disease. Thorax 1988;43:388–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaddoura S, Patel D, Parameshwar J, et al. Objective assessment of the response to treatment of severe heart failure using a 9-minute walk test on a patient-powered treadmill. J Card Fail 1996;2:133–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morice A, Smithies T. The 100 m walk: a simple and reproducible exercise test. Br J Dis Chest 1984;78:392–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly JE, Jacobsen DJ, Jakicic JM, et al. Estimation of peak oxygen consumption from a sub-maximal half mile walk in obese females. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1992;16:585–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oja P, Laukkanen R, Pasanen M, et al. A 2-km walking test for assessing the cardiorespiratory fitness of healthy adults. Int J Sports Med 1991;12:356–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kline GM, Porcari JP, Hintermeister R, et al. Estimation of VO2max from a one-mile track walk, gender, age, and body weight. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1987;19:253–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens D, Elpern E, Sharma K, et al. Comparison of hallway and treadmill six-minute walk tests. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160(5 Pt 1):1540–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaumont A, Cockcroft A, Guz A. A self paced treadmill walking test for breathless patients. Thorax 1985;40:459–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swerts PM, Mostert R, Wouters EF. Comparison of corridor and treadmill walking in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther 1990;70:439–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simonsick EM, Gardner AW, Poehlman ET. Assessment of physical function and exercise tolerance in older adults: reproducibility and comparability of five measures. Aging (Milano) 2000;12:274–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, et al. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA 2006;295:2018–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumurgier J, Elbaz A, Ducimetière P, et al. Slow walking speed and cardiovascular death in well functioning older adults: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harwood RH, Conroy SP. Slow walking speed in elderly people. BMJ 2009;339:b4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall WJ. Update in geriatrics. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:538–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cesari M. Role of gait speed in the assessment of older patients. JAMA 2011;305:93–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beneke R, Meyer K. Walking performance and economy in chronic heart failure patients pre and post exercise training. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1997;75:246–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011;305:50–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanaway FF, Gnjidic D, Blyth FM, et al. How fast does the Grim Reaper walk? Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis in healthy men aged 70 and over. BMJ 2011;343:d7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people—results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1675–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, et al. Added value of physical performance measures in predicting adverse health-related events: results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:251–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavanagh T, Hamm LF, Beyene J, et al. Usefulness of improvement in walking distance versus peak oxygen uptake in predicting prognosis after myocardial infarction and/or coronary artery bypass grafting in men. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1423–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiaranda G, Myers J, Mazzoni G, et al. Peak oxygen uptake prediction from a moderate, perceptually regulated, 1-km treadmill walk in male cardiac patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2012;32:262–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, 8th edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruopp MD, Perkins NJ, Whitcomb BW, et al. Youden index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom J 2008;50:419–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SJ, Hidler J. Biomechanics of overground vs. treadmill walking in healthy individuals. J Appl Physiol 2008;104:747–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouchard C, Malina RM, Perusse L. Genetics of fitness and physical performance. Human Kinetics, 1997:330–4 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw LJ, Hachamovitch R, Redberg RF. Current evidence on diagnostic testing in women with suspected coronary artery disease: choosing the appropriate test. Cardiol Rev 2000;8:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulati M, Pandey DK, Arnsdorf MF, et al. Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women. The St James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation 2003;108:1554–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolea MI, Costa PT, Terracciano A, et al. Sex-specific correlates of walking speed in a wide age-ranged population. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2010;65B:174–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.