Abstract

Multicellular animals rapidly clear dying cells from the organism. Many of the pathways that mediate this cell removal are conserved through evolution. Here we identify srgp-1 as a negative regulator of cell clearance in both C. elegans and mammalian cells. Loss of srgp-1 function results in improved engulfment of apoptotic cells whereas srgp-1 over-expression inhibits apoptotic cell corpse removal. We show that SRGP-1 functions in engulfing cells and acts as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for CED-10(Rac1). Interestingly, loss of srgp-1 function promotes not only the clearance of already dead cells, but also the removal of cells that have been brought to the verge of death through sublethal apoptotic, necrotic or cytotoxic insults. By contrast, impaired engulfment allows damaged cells to escape clearance, which results in increased long-term survival. We propose that C. elegans uses the engulfment machinery as part of a primitive, but evolutionarily conserved survey mechanism that identifies and removes unfit cells within a tissue.

Multicellular organisms use programmed cell death (apoptosis) to remove cells that are superfluous or potentially dangerous1, 2. Apoptotic cells are immediately recognized, engulfed and digested by neighboring or specialized cells. Compromised clearance of cell corpses results in the persistence of unwanted cell debris which can lead to inflammation or autoimmune diseases3. The development of therapeutic approaches that increase engulfment activity could thus be useful in treating such diseases.

The mechanisms underlying apoptotic cell engulfment are evolutionary conserved4. Genetic studies in C. elegans led to the identification of three “partially redundant” signaling pathways that mediate engulfment and degradation of apoptotic cells (Figure S1). One pathway uses two transmembrane proteins, CED-7(ABCA1 in humans) and CED-1(MEGF10), which might function as receptors for dying cells5, 6. The adaptor protein CED-6(GULP) transduces signal(s) from CED-1 further downstream to CED-10(Rac1) and potentially regulates how proteins (e.g. DYN-1, RAB-7) are recruited to the phagosome7–9. In the second signaling cascade two Rho GTPases act in a serial manner: The RhoGEF UNC-73(TRIO) activates MIG-2(RhoG), which in turn regulates and/or recruits to the membrane the bipartite CED-12(Elmo)/CED-5(Dock180) GEF complex, which acts as a GEF for CED-10/Rac110–12. GTP loading of CED-10 is further facilitated by the adaptor molecule CED-2(CrkII)13–15. The two pathways likely converge at the level of CED-10, which promotes the extensive cytoskeletal rearrangements required for engulfment8. In the third pathway, ABL-1(Abl) kinase opposes cell clearance through ABI-1(Abi), possibly via modulation of CED-10 activity16.

Recently, MOM-5(Frizzled) has been shown to act as a major receptor in the recognition of early embryonic corpses. Genetic analyses suggested that MOM-5 regulates CED-10 activity via CED-2, likely through an atypical Wnt signaling pathway that includes GSK-3(GSK3β) and APR-1(APC)17. Additionally, the two integrins INA-1(Integrin α) and PAT-3(Integrin β) play a redundant role in corpse recognition and might also recruit CED-2 to the phagocytic cup in a phospho-tyrosine dependent manner through SRC-1(Src)18. Taken together, these observations suggest that CED-10 is at the center of most, or eventually all signaling pathways that control cell corpse clearance.

Rho GTPase superfamily members such as MIG-2 and CED-10 cycle between GTP-bound (‘on’) and GDP-bound (‘off’) states. GTP loading is promoted by Guanosine exchange factors (GEFs), whereas GTP hydrolysis is facilitated by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs). GEFs for both MIG-2 and CED-10 have been identified, however, GAPs affecting cell corpse engulfment are not known yet.

To identify the GAPs for MIG-2 and CED-10, we compiled a list of all C. elegans genes predicted to contain a RhoGAP domain (Table S1)19, 20. We hypothesized that in engulfment deficient animals, knockdown by RNA interference (RNAi) of RhoGAPs involved in cell corpse clearance would lead to a partial regain of engulfment activity (by the use of Acridine Orange, see Figure S2 and Materials and Methods).

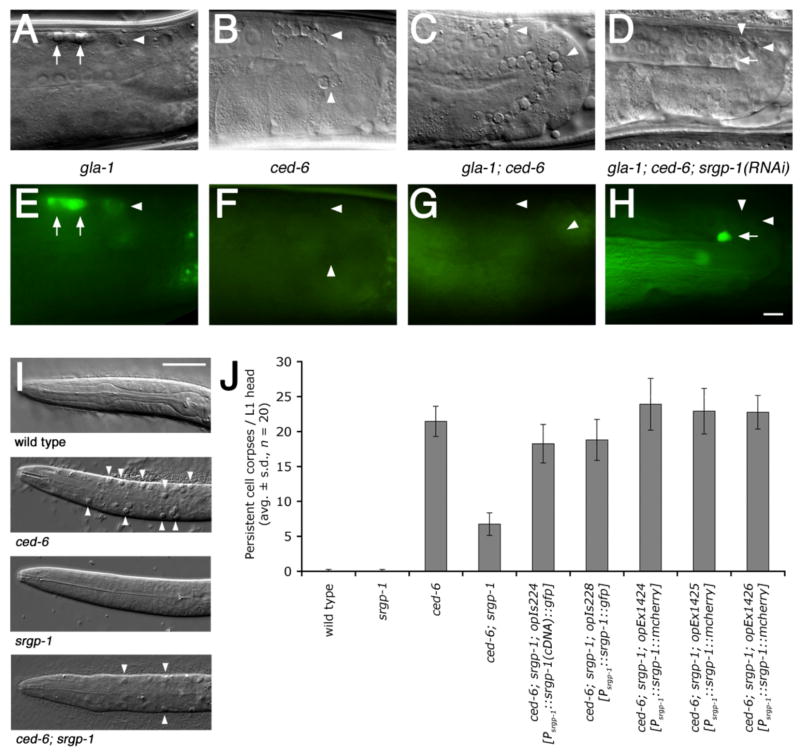

Using this approach, we identified a single gene, srgp-1 (Slit-Robo GAP homolog), whose knockdown resulted in a significant improvement in activity in both ced-5 and ced-6 mutant backgrounds (Figure 1A–H and Table S1). We could also test two srgp-1 mutants, ok300 and tm3701, to confirm our RNAi results (Figure S3 & S4). These two mutant alleles also reduced the number of persistent cell corpses in the head of freshly hatched ced-6 L1 larvae. (Figure 1I & S5). This effect could be reversed through transgenic expression of SRGP-1 driven by the endogenous srgp-1 promoter (Figure 1J). This confirmed that the phenotype observed in srgp-1 mutant worms was due to loss of srgp-1 function.

Figure 1. Loss of srgp-1 activity reduces the numbers of persistent apoptotic cell corpses in C. elegans.

(A–H) srgp-1(RNAi) re-allows Acridine Orange (AO) straining (indicative of engulfment) of germ cell corpses in ced-6 mutants. Adult hermaphrodites of the indicated genotypes were stained with AO as described in Materials and Methods and observed under DIC (A–D) and fluorescence microscopy (E–H). All strains carry a gla-1 mutation in order to increase the overall number of apoptotic germ cells. Arrows point to AO-positive and arrowheads to AO-negative germ cell corpses. In all pictures, anterior is to the left, dorsal on top. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(I) Loss of srgp-1 reduces the numbers of persistent apoptotic cell corpses (arrowheads) in the head of ced-6 L1 larvae. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(J) Expression of srgp-1::gfp or srgp-1::mcherry driven by the endogenous srgp-1 promoter rescues the srgp-1(ok300) phenotype. Persistent cell corpses were scored in the head region of freshly hatched L1 larvae of the indicated genotypes. Data are shown as average ± standard deviation (avg. ± s.d.); n, number of scored individuals.

Alleles used: gla-1(op234), ced-6(n1813), srgp-1(ok300), opIs224[Psrgp-1::srgp-1(cDNA)::gfp], opIs228[Psrgp-1::srgp-1(genomic)::gfp] and opEx1424-6[Psrgp-1::srgp-1(genomic)::mcherry].

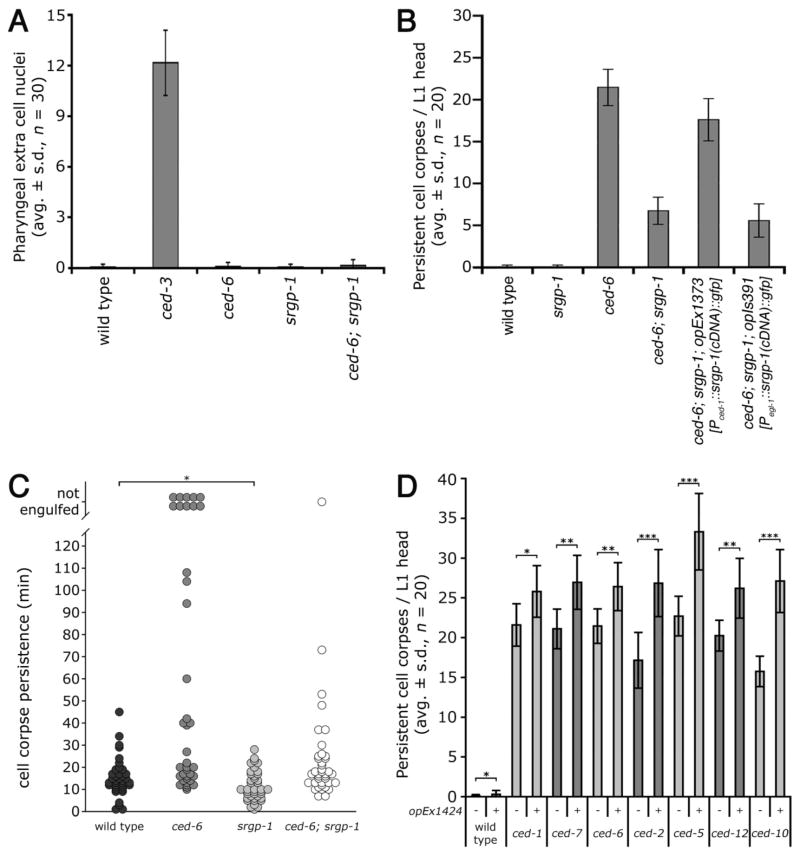

The reduction in persistent apoptotic cell corpses in srgp-1 mutants could have arisen either from a reduction in apoptosis or an increased engulfment activity. We took advantage of the well-characterized fixed cell lineage in nematodes to directly test both hypotheses21. 16 cells undergo programmed cell death in the anterior pharynx in wild-type animals, and can be scored as extra cell nuclei (“undead cells”) in apoptosis-defective ced-3(lf) mutants. However, in srgp-1 mutants no extra surviving nuclei could be identified, suggesting that developmental apoptosis is not affected by srgp-1 (Figure 2A). We also used 4-dimensional microscopy to follow the first 13 embryonic cell deaths21. We observed that the overall development and developmental apoptosis are neither aberrant nor delayed in srgp-1 mutant embryos (Figure S6). By contrast, we found a striking decrease in corpse persistence in each three different ced-6; srgp-1 embryos compared to ced-6 single mutants: 10 cell corpses failed to be engulfed in ced-6 embryos, whereas only 1 such persistent corpse was left in ced-6; srgp-1 embryos (Figure 2C and Table S2). Cell corpse persistence was also reduced in the srgp-1 single mutant compared to wild type (p < 0.005). These observations suggest that loss of SRGP-1 function results in increased engulfment activity rather than in reduced apoptosis.

Figure 2. SRGP-1 acts in the engulfing cell and antagonizes engulfment activity.

(A) Developmental apoptosis is not defective in srgp-1 mutants. Extra cell nuclei were scored in the pro- and metacorpus in L3/L4 larval heads of the indicated genotypes. Alleles used: ced-3(n2433), ced-6(n1813) and srgp-1(ok300).

(B) Focus of action analysis: expression of srgp-1::gfp in the engulfing cell (opEx1373) rescues the srgp-1(ok300) phenotype; expression in apoptotic cells (opIs391) does not. Alleles used: ced-6(n1813), srgp-1(ok300), opEx1373[Pced-1::srgp-1(cDNA)::gfp] and opIs391[Pegl-1::srgp-1(cDNA)::gfp].

(C) Loss of srgp-1 increases engulfment kinetics. The first 13 apoptotic cell deaths in the AB lineage were followed by 4D microscopy and the cell corpse persistence was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each circle represents a single cell. Analysis was performed in three independent individuals in each genetic background (n = 3 × 13 cells). Cells indicated as not engulfed either floated off the tissue into the egg-shell cavity or their lineage could not be followed anymore due to the beginning of muscle contraction at the 1.5-fold stage (320 min post fertilization or ≈ 120 min post onset of cell death). Alleles used: ced-6(tm1826) and srgp-1(ok300). * p < 0.005 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

(D) Over-expression of srgp-1::mcherry enhances corpse persistence. Persistent cell corpses were scored in the head region of freshly hatched L1 larvae of the indicated genotypes. Alleles used: ced-1(e1735), ced-2(n1994), ced-5(n1812), ced-6(n1813), ced-7(n1996), ced-10(n1993) and ced-12(k149). Indicated strains carried unc-119(ed3) and the opEx1424[Psrgp-1::srgp-1::mcherry] transgene. * p ≤ 0.02, ** p < 10−6 and *** p < 10−10 (t-test, 1-tailed, unequal variances).

To determine the SRGP-1 expression pattern, we analyzed the rescuing transgene opIs228[Psrgp-1::srgp-1::gfp] (Figure S7). Consistent with the neuronal function of srGAP proteins in vertebrates, we found expression in the nerve ring and in some projecting sensory neurons at the tip of the head. In larvae and adults, SRGP-1 is abundantly expressed in hypodermal tissues (Figure S7C, D & E). SRGP-1::GFP localizes to the cortex of all cells in early embryos, and is particularly abundant around highly condensed (i.e. late) apoptotic cell corpses (Figure S7A & B). A similar enrichment around corpses has been observed for a number of genes involved in corpse removal5, 22, suggesting that SRGP-1 might function in engulfing cells. To directly test this hypothesis, we expressed srgp-1::gfp in a “tissue-specific” manner. Expression in the dying cell using the egl-1 promoter23 did not affect cell corpse numbers, whereas expression in the engulfing cell using the ced-1 promoter provided significant rescue (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that SRGP-1 functions in engulfing rather than in dying cells.

Since loss of srgp-1 function in engulfing cells results in increased engulfment activity, we asked whether over-expression of srgp-1 in engulfing cells could cause the opposite effect, namely inhibit cell corpse engulfment. We found that the rescuing transgene opEx1424[Psrgp-1::srgp-1::mcherry], an extra-chromosomal high-copy array that likely results in srgp-1::mcherry over-expression, significantly enhanced the persistent cell corpse phenotype of all engulfment mutants tested (Figure 2D). These results support the hypothesis that SRGP-1 is a direct negative regulator of engulfment activity in C. elegans.

To determine where within the engulfment signaling cascade srgp-1 acts, we generated double mutants between srgp-1 and various engulfment genes and scored numbers of apoptotic cell corpses in freshly hatched larval L1 heads. We found that, in addition to ced-6, several ced-1 and ced-7 mutant alleles were also partially suppressed by srgp-1(ok300) (Table 1A). We also scored directly for engulfment activity by visualizing F-actin formation around apoptotic corpses during the internalization process8. In all genotype tested, loss of srgp-1 led to a significant increase in cell corpses covered with actin halos (indicative of active engulfment signaling) (Figure S8 and Table S3). srgp-1 thus likely acts downstream or in parallel to the ced-1, -7, -6 signaling cascade.

Table 1. srgp-1 acts downstream of or in parallel to the two engulfment signaling pathways.

Engulfment: Persistent cell corpses were scored in the head of L1 larvae of the indicated genotypes. Asterisk, corpse numbers were scored in early four fold embryos as dyn-1(n4039) embryos fail to hatch. Data are shown as average ± standard deviation.

Cell migration: Adult worms with gonads that deviated from the wild type U-shaped tube were scored as DTC-defective, as described in materials and methods. n.d., not done.

| A Loss of srgp-1 reduces ced-7, ced-1, ced-6 and dyn-1 mutant persistent cell corpses.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Corpses/L1 head (DIC, n = 20) | % mismigrated DTC (n ≥ 100) |

| wild type | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.4 |

| srgp-1(ok300) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 8.5 |

| ced-7(n1996) | 21.1 ± 2.5 | n.d. |

| ced-7(n1996); srgp-1(ok300) | 12.2 ± 3.5 | n.d. |

| ced-7(n2690) | 21.4 ± 3.2 | n.d. |

| ced-7(n2690); srgp-1(ok300) | 12.7 ± 3.2 | n.d. |

| ced-1(e1735) | 21.6 ± 2.7 | n.d. |

| ced-1(e1735); srgp-1(ok300) | 13.6 ± 2.7 | n.d. |

| ced-1(n1995) | 6.9 ± 2.5 | n.d. |

| ced-1(n1995); srgp-1(ok300) | 2.4 ± 1.6 | n.d. |

| ced-6(n1813) | 21.5 ± 2.2 | n.d. |

| ced-6(n1813); srgp-1(ok300) | 6.3 ± 2.2 | n.d. |

| ced-6(tm1826) | 24.3 ± 2.1 | n.d. |

| ced-6(tm1826); srgp-1(ok300) | 10.8 ± 3.4 | n.d. |

| ced-6(op360) | 10.4 ± 2.3 | n.d. |

| ced-6(op360); srgp-1(ok300) | 3.7 ± 1.7 | n.d. |

| dyn-1(n4039) | * 20.1 ± 3.8 | n.d. |

| srgp-1(ok300); dyn-1(n4039) | * 9.6 ± 2.9 | n.d. |

| B Loss of srgp-1 reduces mig-2, ced-2, ced-5, ced-12 and ced-10 mutant persistent cell corpses and DTC migration defects.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Corpses/L1 head (DIC, n = 20) | % mismigrated DTC (n≥ 100) |

| ced-2(n1994) | 17.2 ± 3.5 | 28.2 |

| ced-2(n1994) srgp-1(ok300) | 9.3 ± 2.1 | 14.0 |

| ced-2(e1752) | 15.6 ± 2.6 | 38.3 |

| ced-2(e1752) srgp-1(ok300) | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 15.4 |

| ced-5(n1812) | 22.7 ± 2.5 | 43.9 |

| ced-5(n1812) srgp-1(ok300) | 11.8 ± 2.4 | 45.0 |

| ced-5(tm1949) | 24.1 ± 2.0 | 46.7 |

| ced-5(tm1949) srgp-1(ok300) | 12.8 ± 2.7 | 29.0 |

| ced-12(k149) | 20.3 ± 1.9 | 29.2 |

| ced-12(k149); srgp-1(ok300) | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 11.9 |

| ced-12(bz187) | 18.9 ± 2.4 | 33.1 |

| ced-12(bz187); srgp-1(ok300) | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 17.3 |

| ced-12(oz167) | 18.5 ± 3.2 | 34.9 |

| ced-12(oz167); srgp-1(ok300) | 8.7 ± 2.4 | 14.7 |

| ced-10(n3246) | 20.8 ± 2.6 | 41.7 |

| ced-10(n3246) srgp-1(ok300) | 15.0 ± 2.6 | 40.8 |

| ced-10(n1993) | 15.8 ± 1.9 | 31.8 |

| ced-10(n1993) srgp-1(ok300) | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 28.3 |

| ced-10(t1875) | n.d. | 51.8 |

| ced-10(t1875) srgp-1(ok300) | n.d. | 50.0 |

| mig-2(mu28) | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 25.0 |

| srgp-1(ok300); mig-2(mu28) | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 15.2 |

| ced-2(e1752) | 15.6 ± 2.6 | 38.3 |

| ced-2(e1752) srgp-1(ok300) | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 15.4 |

| ced-2(e1752); mig-2(mu28) | 30.7 ± 4.8 | 41.5 |

| ced-2(e1752) srgp-1(ok300); mig-2(mu28) | 16.6 ± 2.0 | 25.6 |

Genes in the second signaling pathway (e.g. ced-2, -5, -12) mediate not only cell corpse clearance, but also a number of cell migration processes. For example, mutants in this pathway show a severe distal tip cell (DTC) migration defect. Interestingly, the srgp-1(ok300) mutation could partially suppress both persistent cell corpses and DTC migration defects in most of the analyzed double mutants, suggesting that SRGP-1 acts as a negative regulator in both processes (Table 1B, Figure S8 and Table S3). Importantly, srgp-1 could suppress a null allele of the RhoG homologue mig-2(mu28), suggesting that MIG-2 is not the major target of SRGP-1.

Two hypomorphic ced-10 alleles, n1993 and n3246 (membrane targeting and GTP-binding defective, respectively), were also partially suppressed by srgp-1(lf). Unfortunately, the ced-10(t1875) null allele could not be scored in the L1 corpse assay due to embryonic lethality24. As an alternative, we used AO staining to measure the ability of srgp-1(ok300) to promote the uptake/internalization of germ cell corpses in ced-5, ced-6 and maternally rescued ced-10(null) mutants. We found that loss of srgp-1 leads to increased numbers of AO+ corpses in ced-5 and ced-6, but not ced-10(null) mutants (Figure S9). Similarly, DTC migration defects in maternally rescued homozygote ced-10(null) hermaphrodites were not suppressed in srgp-1 mutants (Table 1B). We thus conclude that srgp-1(ok300) cannot compensate for the loss of CED-10(Rac1) activity. Taken together, our results suggest that SRGP-1 acts downstream of most engulfment genes, and possibly functions either onto, or in parallel to CED-10(Rac1).

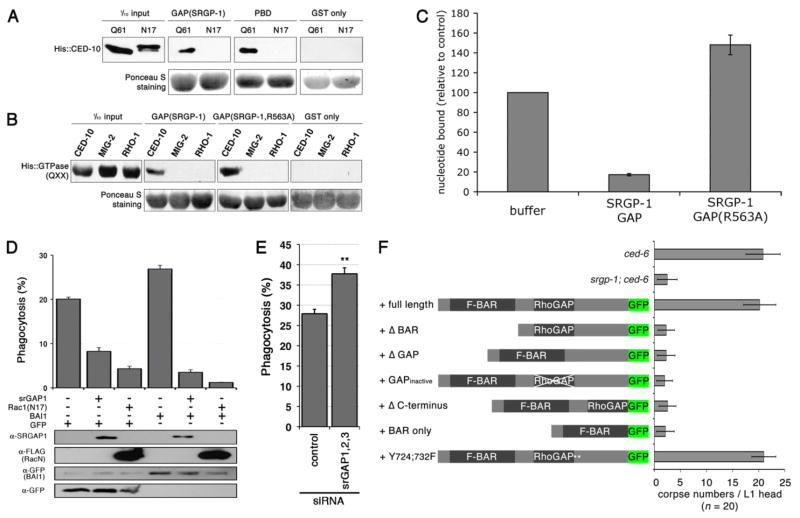

Given our genetic epistasis data, we tested the possibility that SRGP-1 acts as a GAP for CED-10. We performed in vitro binding assays between SRGP-1 and CED-10 variants that mimic the GTP- and GDP-bound states (Q61L and T17N, respectively). We found that the SRGP-1 GAP domain specifically interacted with the GTP-bound, but not GDP-bound CED-10 protein (Figure 3A); this is consistent with the property of GAP proteins to associate with the GTP-bound version of GTPases. SRGP-1 GAP failed to bind to GTP-bound MIG-2 and RHO-1, two other Rho family members, demonstrating the specificity of the SRGP-1/CED-10 interaction (Figure 3B). Importantly, we found that the SRGP-1 GAP domain can enhance the intrinsic GTPase activity of mammalian Rac1, albeit at relatively high molar concentrations with respect to mammalian Rac1 (Figure 3C). To further confirm this result, we mutated the conserved arginine finger in the SRGP-1 GAP domain that has been previously shown to be necessary in other GAP domains25. This mutant SRGP-1(R563A), although it could bind the GTPase, failed to enhance GTPase activity (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. SRGP-1(srGAP1) binds to and modulates CED-10(Rac1) GTPase activity.

(A) The GAP domain of SRGP-1 specifically binds GTP-loaded CED-10 in vitro. The Q61 and N17 isoforms (resembling GTP- and GDP-bound, respectively) of His-tagged CED-10 were used for GST-fusion pull down using the GAP domain of SRGP-1, Pak1 p21 binding domain (PBD, positive control) and GST alone (negative control).

(B) The SRGP-1 GAP domain preferentially binds to CED-10 in vitro. The GTP-bound isoforms of His-tagged CED-10, MIG-2 and RHO-1 (Q61, Q65 and Q63, respectively) were used for GST-fusion pull down using the GAP domain of SRGP-1, the GTP hydrolysis-deficient GAP(R563A) and GST alone.

(C) The SRGP-1 GAP domain promotes Rac1 GTP-hydrolysis in vitro. GTP-hydrolysis of human Rac1 (loaded with [γ-32P]GTP) was measured by the loss of radioactivity of Rac1 as a result of the cleavage of the γ-32P from GTP. As controls, loaded Rac1 was treated with buffer alone or the GTP hydrolysis-deficient GAP(R563A). Data are shown as average ± standard deviation (avg. ± s.d., n = 4 independent experiments).

(D) srGAP1 function in corpse removal is evolutionarily conserved. LR73 cells were transiently transfected in triplicate with the indicated plasmids (srGAP1, FLAG::Rac1(N17), BAI1::GFP or GFP alone, respectively). Phagocytosis by GFP-positive cells was assessed by two-color flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP-positive cells that had ingested apoptotic SCI cells is indicated for each condition. The expression of the transfected proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting of total lysates as indicated.

(E) srGAP family members inhibit cell corpse clearance. Knock down of all 3 srGAP(1-3) family members increases phagocytotic activity in LR73 cells. Knockdown of the individual family members and corresponding phagocytic activities are shown in Figure S11.

(F) in vivo structure/function analysis of SRGP-1. GFP fusions of srgp-1(cDNA) full length, Δ BAR, Δ GAP, GAP inactive (Δ FRV (Δ aa 562-4)), Δ C-terminus, BAR only and Y(724;732)F were tested for rescue ability in ced-6; srgp-1 mutants. Persistent cell corpses were scored in the head region of freshly hatched L1 larvae of the indicated genotypes. Data are shown as average ± standard deviation. Alleles used: ced-6(n1813) and srgp-1(ok300).

The ability of C. elegans SRGP-1 to act on mammalian Rac1 suggested that the function of srGAP in the regulation of cell corpse clearance might be evolutionary conserved. We tested this hypothesis by looking at the engulfment of apoptotic Jurkat cells by Chinese hamster ovary LR73 cells. These cells show a basal phagocytic activity, which can be stimulated by over-expression of BAI1, a receptor upstream of Rac1 involved in cell corpse clearance in mammalian models26. We could inhibit the engulfment activity of LR73 cells by over-expression either of a dominant negative Rac1(N17), or of the mammalian srGAP1 protein (Figure 3D). By contrast, we found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of individual srGAP family members had only a minor effect on engulfment activity, possibly due to compensatory increases in gene expression of other family members (Figure S10). However, the simultaneous knock-down of all three srGAP family members resulted in a significant increase in engulfment activity (Figure 3E). Taken together, these observations clearly suggest that the srGAP family members, and in particular srGAP1, can also function to inhibit cell corpse clearance in mammals.

To further support our in vitro results, we also performed an in vivo structure/function analysis. We created a variety of rescue constructs encoding for SRGP-1 derivatives lacking various domains in the SRGP-1 protein. All constructs expressed at levels similar to those of the full-length protein (our unpublished observations). SRGP-1 modifications that lead to SRGP-1 mislocalization (Δ BAR), or abrogated GAP activity (Δ GAP, GAPinactive and BAR only) resulted in a complete loss of rescuing activity (Figure 3F). The Δ C-terminus construct also failed to rescue; the reason for this is currently unknown, as this construct showed a nearly wild-type expression pattern. However, the modification of two tyrosines (Y724;732F) predicted to be regulated by phosphorylation27 did not alter the rescuing ability, suggesting that phosphorylation of these two residues is not essential for SRGP-1 function.

The wide range of BAR superfamily members regulate invaginations and protrusions of plasma membranes28. For example, F-BAR domain-containing FCHo1/2 are required for plasma membrane clathrin-coated vesicle formation29. Contrary, the I-BAR domain of the human srGAP2 is necessary and sufficient for membrane localization and the induction of filopodia-like membrane protrusions30. Interestingly, the SRGP-1 F-BAR domain failed to rescue the corpse clearance phenotype in our assays, suggesting distinct modes of action of srGAP family members and its BAR domains in these two processes.

Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo results strongly suggest an evolutionary conserved function for SRGP-1 as a GAP for CED-10(Rac1) in cell corpse clearance. In vivo, loss of srgp-1 function results in enhanced engulfment signaling, which can partially suppress the cell corpse clearance defects of engulfment mutants. We suspect that interventions that increase engulfment signaling would thus also be effective in treating human diseases characterized by defective cell clearance.

Three other negative regulators of C. elegans cell corpse engulfment have recently been described16, 31, 32. Interestingly, two have been suggested to act on (or in parallel to) CED-10(Rac1), and one on its CED-5/CED-12 GEF complex. Our double mutant analysis suggests that srgp-1 acts in parallel to at least 2 of those, mtm-1 and abl-1 (Figure S11). The multitude of regulatory molecules acting on CED-10(Rac1) emphasizes the key position of this GTPase in the engulfment signaling pathways. However, it is likely that additional regulators exist that act at other points within these pathways.

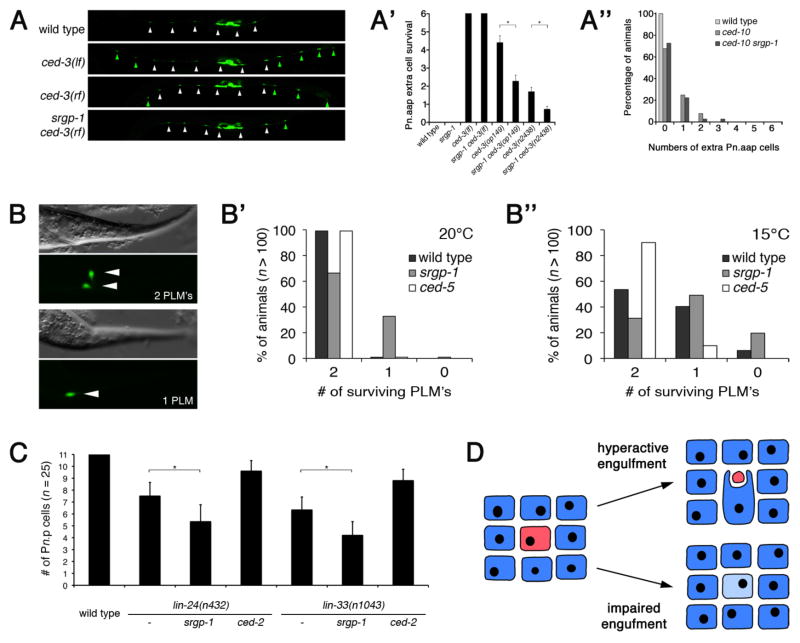

We and others have previously shown that under conditions of limiting caspase activity (e.g. weak reduction-of-function (rf) ced-3 mutants), loss of engulfment activity not only leads to corpse persistence, but also promotes survival: in such ced-3(rf) backgrounds, significantly more cells survive in engulfment-defective mutants than in control strains33, 34. We could not test whether over-activated engulfment signaling (such as in srgp-1 mutants) will cause an opposite phenotype, and drive the death of cells that would have otherwise survived. We first looked at ventral cord development, where six of the twelve Pn.aap cells (P1, P2 and P9–P12) undergo programmed cell death. The two reporter transgenes nIs96 and nIs106 express GFP in all differentiated Pn.aap cells [Plin-11::gfp], and thus can be used to score the survival of these cells (Figure 4A). About 50% of the surviving Pn.aap cells found in ced-3(rf) mutants did not survive in srgp-1 ced-3(rf) double mutants (Figure 4A′). This “killer”-phenotype of srgp-1(lf) mutants was dependent on ced-10, as no increased cell death could be observed in ced-10(0) srgp-1 double mutants (Figure 4A″). A similar effect was observed in the pharynx, where srgp-1(ok300) reduced the number of surviving cells by ~50% in two distinct ced-3(rf) alleles (Figure S12). Importantly, in no case did we observe the loss of cells that are not normally fated to die, or that failed to undergo programmed cell death due to complete loss of the apoptotic pathway (e.g. strong ced-3(lf) mutants, Figure 4A′ and S12). Taken together, our results demonstrate that increased engulfment activity, as in srgp-1 mutants, can promote the removal of cells that are viable but close to death under conditions of limiting caspase activity.

Figure 4. Enhanced engulfment promotes the removal of viable but sick cells in C. elegans.

(A–A″) Loss of srgp-1 promotes killing of cells on the verge of apoptotis in the larval ventral cord. The 12 blast cells (P1–P12) divide post-embryonically to generate the Pn.aap motor neurons of the ventral cord, labeled here by the nIs96[Plin-11::gfp] reporter33. P3.aap – P8.aap generate the VC motor neurons (white arrowheads) that innervade the vulval muscles. P1.aap, P2.aap and P9.aap - P12.aap undergo programmed cell death in the wild type, but survive in apoptosis defective ced-3(lf) animals and differentiate into VC-like neurons (green arrowheads). (A) Representative wild type, ced-3(lf) (loss-of-function), ced-3(rf) (reduction-of-function) and srgp-1 ced-3(rf) L4 larvae are shown. Alleles used: ced-3(lf) = n717, ced-3(rf) = op149 and srgp-1(ok300), nIs96 is present in all backgrounds. Scale bar, 100 μm (A′) Quantification of Pn.aap extra cell survival (P1, P2 & P9–P12, labeled by green arrowheads) monitored in the indicated genotypes using the nIs96 transgene. srgp-1(lf) is not sufficient to kill cells that normally survive (P3.aap – P8.aap). Alleles used: ced-3(n717lf), ced-3(op149rf), ced-3(n2438rf), and srgp-1(ok300). Data shown are avg. ± s.d. of 3 experiments, n ≥ 40 animals/exp. * p < 10−10 (t-test, 1-tailed, unequal variances). (A″): Enhanced cell killing in srgp-1 mutants is ced-10-dependent. Extra cells in the ventral cord in wild type, ced-10(t1875) and ced-10(t1875) srgp-1(ok300) were scored using the nIs106[Plin-11::gfp] transgene33 (n ≥ 100 per genotype). ced-10 animals were generated from heterozygote mothers.

(B–B″) Engulfment activity modulates the removal of viable cells subjected to a neurotoxic insult. (B) The Ismec-10(d) transgene induces weak temperature-sensitive neurotoxic cell death through over-expression of MEC-10(A673V), which codes for a leaky DEG/ENaC channel in the six touch neurons38. Survival of the PLM touch neurons (labeled with GFP) was quantified in L4 larvae grown up at either 20°C (B′) or 15°C (B″) of the indicated genotype. Alleles used: ced-5(tm1949) and srgp-1(ok300), Ismec-10(d) is present in all genetic backgrounds. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(C) Engulfment activity modulates the removal of viable cells subjected to a non-classical toxic insult. In animals carrying gain-of-function mutations in either lin-24 or lin-33, some of the Pn.p hypodermal blast cells increase in refractivity and form non-circular (oval) shaped bodies that persist from several minutes up to 3 hours in L1 larvae. Subsequently, these cells are either removed or they survive (and recover) 36. The number of surviving Pn.p cells were scored in early L3 larvae based on DIC optics. Data shown are avg. ± s.d., n = 25. * p < 10−4 (t-test, 1-tailed, unequal variances). Alleles used: srgp-1(ok300) and ced-2(e1752).

(D) Simplified model of sick cell tolerance vs. removal (see text).

The C. elegans engulfment pathway has been reported to mediate the removal not only of apoptotic cells, but also of cells that die by necrosis or other, non-canonical pathways35, 36. For example, necrosis-like death can be induced in C. elegans by rare gain-of-function (gf) mutations in various ion channels coding genes (DEG/ENaC family members mec-4, mec-8 and mec-10). As a result, these channels are leaky, causeing osmotic imbalance, cell swelling, and ultimately cell lysis37. We used the transgene Ismec-10(d) expressing MEC-10(A673V) and GFP in the six mechanosensory touch cell neurons, which induces an incompletely penetrant, temperature sensitive neurotoxic cell death38. As a result, some touch cells undergo necrotic cell death, others recover from the insult and survive. As with apoptotic cell death, we found that hyperactive engulfment activity (srgp-1 mutants) promotes cell removal, whereas impaired engulfment (ced-5 mutants) leads to increased cell survival (Figure 4B–B″).

Horvitz and colleagues recently reported a new type of non-apoptotic, cytotoxic cell death induced by either lin-24(gf) or lin-33(gf) in C. elegans36. A fraction of affected Pn.p hypodermal blast cells undergoes morphological changes (distinct from apoptotic or necrotic cell death); they either die and are cleared, or they survive and eventually recover from the insult. Interestingly, modulation of the engulfment machinery also influences cell survival in this model of cytotoxic cell death: engulfment-defective mutants showed an increased Pn.p cell survival (Figure 4C, also previously observed by Galvin et. al.36), whereas hyperactive engulfment led to decreased Pn.p cell survival.

Based on these observations, it is tempting to speculate that the engulfment pathway might be used generally by C. elegans to identify and eliminate sick or damaged cells (Figure 4D). We propose that sick cells within a tissue signal their unhealthy status to their neighbor. Depending on the strength of this signal, the sick cell is either tolerated (light blue), or removed (red, “eaten alive”) via phagocytosis. In animals with a hyperactive engulfment pathway, even weak signals lead to cell removal. Conversely, in engulfment-defective mutants, even highly unhealthy cells are tolerated allowing them to possibly recover and survive.

It is interesting to speculate that this type of tissue quality control, in which cells sense and eliminate unfit neighbors, might provide the basis for more sophisticated regulatory mechanisms, such as cell competition. Indeed, Li and Baker recently reported the involvement of several engulfment genes in cell competition during Drosophila development39. Given the conservation of the engulfment pathway throughout metazoa, the possibility to recognize and remove sick but viable cells might also be present in mammals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Hengartner lab members for comments and discussions on this manuscript, M. Weiss for statistical advice and M. Jovanovic for in vivo pull-down supports. Some strains were supplied by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC), the C. elegans knock-out consortium (Oklahoma, USA) and the National Bioresource Project (Japan). This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association and American Cancer Society (to J. M. K.), the NIGMS/NIH (to K. S. R., a William Benter Senior Fellow of the American Asthma Foundation), the Junta de Castilla y León (grant CSI03A08) and the Riojasalud Foundation (J. C.), the Junta de Castilla y León (Grupo de Excelencia GR265) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grants BFU2008-01808 and Consolider CSD2007-00015) (S. M.), the NIH postdoctoral training grant GM078747 and the fellowship from the Machiah Foundation (R. Z.-B.), the Swiss National Science Foundation, The Ernst Hadorn Foundation and the European Union (FP5 project APOCLEAR) (M. O. H).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

L. J. N., A. P. F. and R. Z.-B. contributed to the generation of nematode transgenics and fluorescence microscopy studies; A. P. F. and L. J. N. conducted the unbiased screen and the epistasis; J. C. performed the 4D microscopic analysis; J. M. K. performed the mammalian cell culture experiments; Z. M. and L. B. H. performed the pull downs and the hydrolysis assays; L. J. N. performed the cell killing assay and wrote the manuscript. A. P. F. and M. O. H. contributed to the data analysis, project planning and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debatin KM. Apoptosis pathways in cancer and cancer therapy. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2004;53:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savill J, Gregory C, Haslett C. Science. 2003;302:1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.1092533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fullard JF, Kale A, Baker N. Apoptosis. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Z, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. CED-1 is a transmembrane receptor that mediates cell corpse engulfment in C. elegans. Cell. 2001;104:43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YC, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell corpse engulfment gene ced-7 encodes a protein similar to ABC transporters. Cell. 1998;93:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X, Odera S, Chuang CH, Lu N, Zhou Z. Developmental Cell. 2006;14 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinchen JM, et al. Two pathways converge at CED-10 to mediate actin rearrangement and corpse removal in C. elegans. Nature. 2005;434:93–99. doi: 10.1038/nature03263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu QA, Hengartner MO. Candidate adaptor protein CED-6 promotes the engulfment of apoptotic cells in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;93:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumienny TL, et al. CED-12/ELMO, a novel member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac pathway, is required for phagocytosis and cell migration. Cell. 2001;107:27–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu YC, Horvitz HR. Nature. 1998;392:501–504. doi: 10.1038/33163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.deBakker CD, et al. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells is regulated by a UNC-73/TRIO-MIG-2/RhoG signaling module and armadillo repeats of CED-12/ELMO. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2208–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddien PW, Horvitz HR. CED-2/CrkII and CED-10/Rac control phagocytosis and cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:131–136. doi: 10.1038/35004000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akakura S, et al. C-terminal SH3 domain of CrkII regulates the assembly and function of the DOCK180/ELMO Rac-GEF. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:344–351. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosello-Trampont AC, et al. Identification of two signaling submodules within the CrkII/ELMO/Dock180 pathway regulating engulfment of apoptotic cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:963–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurwitz ME, et al. Abl kinase inhibits the engulfment of apoptotic [corrected] cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e99. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabello J, et al. The Wnt pathway controls cell death engulfment, spindle orientation, and migration through CED-10/Rac. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu TY, Wu YC. Engulfment of apoptotic cells in C. elegans is mediated by integrin alpha/SRC signaling. Curr Biol. 2010;20:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rual JF, et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30:313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinchen J, Ravichandran K. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:2143–2149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans protein EGL-1 is required for programmed cell death and interacts with the Bcl-2-like protein CED-9. Cell. 1998;93:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel FB, et al. The WAVE/SCAR complex promotes polarized cell movements and actin enrichment in epithelia during C. elegans embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;324:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett T, et al. Nature. 1997;385:458–461. doi: 10.1038/385458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park D, et al. Nature. 2007;450:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suetsugu S, Toyooka K, Senju Y. Subcellular membrane curvature mediated by the BAR domain superfamily proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henne WM, et al. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 328:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerrier S, et al. The F-BAR domain of srGAP2 induces membrane protrusions required for neuronal migration and morphogenesis. Cell. 2009;138:990–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Lu J, Rovnak J, Quackenbush SL, Lundquist EA. SWAN-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans WD repeat protein of the AN11 family, is a negative regulator of Rac GTPase function. Genetics. 2006;174:1917–1932. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou W, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans myotubularin MTM-1 negatively regulates the engulfment of apoptotic cells. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddien PW, Cameron S, Horvitz HR. Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412:198–202. doi: 10.1038/35084096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoeppner DJ, Hengartner MO, Schnabel R. Engulfment genes cooperate with ced-3 to promote cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;412:202–206. doi: 10.1038/35084103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung S, Gumienny TL, Hengartner MO, Driscoll M. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:931–937. doi: 10.1038/35046585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galvin BD, Kim S, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans genes required for the engulfment of apoptotic corpses function in the cytotoxic cell deaths induced by mutations in lin-24 and lin-33. Genetics. 2008;179:403–417. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.087221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mano I, Driscoll M. DEG/ENaC channels: a touchy superfamily that watches its salt. Bioessays. 1999;21:568–578. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199907)21:7<568::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, et al. Intersubunit interactions between mutant DEG/ENaCs induce synthetic neurotoxicity. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1794–1803. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Baker NE. Cell. 2007;129:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.