Abstract

Glycans are key participants in biological processes ranging from reproduction to cellular communication to infection. Revealing glycan roles and the underlying molecular mechanisms by which glycans manifest their function requires access to glycan derivatives that vary systematically. To this end, glycopolymers (polymers bearing pendant carbohydrates) have emerged as valuable glycan analogs. Because glycopolymers can readily be synthesized, their overall shape can be varied, and they can be altered systematically to dissect the structural features that underpin their activities. This review provides examples in which glycopolymers have been used to effect carbohydrate-mediated signal transduction. Our objective is to illustrate how these powerful tools can reveal the molecular mechanisms that underlie carbohydrate-mediated signal transduction.

1. Introduction

All cells, from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, are cloaked in a glycan coat termed the glycocalyx.1, 2 This coat is composed of a variety of glycosylated proteins and lipids that report on cell type, environment, and the metabolic state of the cell. It was originally thought that the primary role of the glycocalyx was to act as a physical barrier against the cell’s environment; however, the presence of carbohydrate-binding proteins on the cell surface augurs the vital role of cell surface glycans in cell–cell recognition. The interaction of cell surface glycans with cell surface carbohydrate receptors is not only important for cell adhesion—it also can trigger signal transduction. This mode of information transfer is fundamental for many biological processes, including fertilization and implantation3–6, pathogen invasion7, immune system activation8, 9 or attenuation10–14, and cell proliferation.15 Recognition of the wide-ranging contributions of glycans to signaling is mounting.16, 17

This growing appreciation of glycan function is providing impetus to develop ligands to probe and perturb protein-carbohydrate interactions. While methods to isolate and characterize glycans from biological sources are advancing, it can be challenging to elucidate the molecular features involved in glycan recognition and function. Chemical synthesis is a powerful ally in addressing this challenge. It offers access to glycans whose structures can be varied to dissect glycan function.18 One especially valuable class of synthetic ligands for illuminating carbohydrate recognition is multivalent displays.

A hallmark of many protein–carbohydrate interactions is multivalency. Most carbohydrate-binding proteins, whether on the cell surface or secreted, are oligomers. They can exist as dimers, trimers, tetramers, or even higher order clusters.19–21 These oligomeric proteins can bind either to multiple carbohydrate residues within a glycan or to multiple glycans on the surface of cells (Figure 1).22–25 The advantages of multivalency have been revealed through chemical biology studies. While it is well-appreciated that multivalent binding can enhance the functional affinity (observed affinity, also termed avidity) of cell surface protein–carbohydrate interactions,22, 26–29 it is often overlooked that multivalent binding can also improve specificity.28, 30 If individual interactions at the cell surface were to occur with high functional affinity, it could be problematic. During the encounter of two cells (one with carbohydrate ligands and the other with a protein-binding partner), for example, the summation of multiple high affinity interactions would render binding irreversible. In contrast, low affinity multivalent interactions are kinetically labile31; therefore, they provide the mean to capture a cell of interest while still allowing for reversibility if the wrong cell type binds initially.19

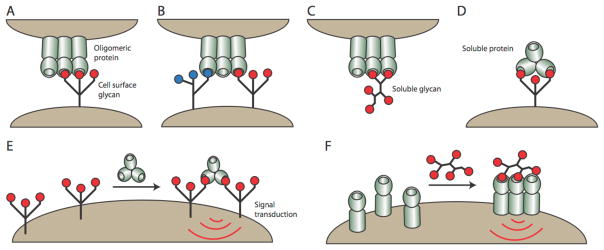

Figure 1.

Carbohydrate-binding proteins exist as oligomers and can interact with glycans through a variety of mechanisms. An oligomeric protein can interact with an individual cell-surface glycan (A) or with multiple different cell-surface glycans simultaneously (B). Oligomeric proteins can also interact with soluble glycans or soluble oligomeric lectins can engage cell surface glycans (C & D). Soluble proteins can cluster cell-surface glycoproteins to mediate signal transduction (E). Likewise, soluble glycans can cluster cell-surface receptors to mediate signal transduction (F).

The properties of multivalent carbohydrate derivatives (i.e., their ability to exhibit high functional affinity and increased specificity) have stimulated the development of methods to synthesize defined multivalent carbohydrate derivatives, including polymers bearing pendant carbohydrates (glycopolymers). These agents can be employed as potent inhibitors, but their ability to cluster carbohydrate receptors provides them with an additional property—they can activate signaling.32 Accordingly, glycopolymers have been used to mimic either polysaccharides (i.e., glycosaminoglycans), glycoproteins, mucins, or even larger entities such as viral particles or clustered glycans in cell surface microdomains.29, 33 Because they are synthetically tractable, these surrogates can be altered to optimize a desired activity or to probe a specific biological process.34

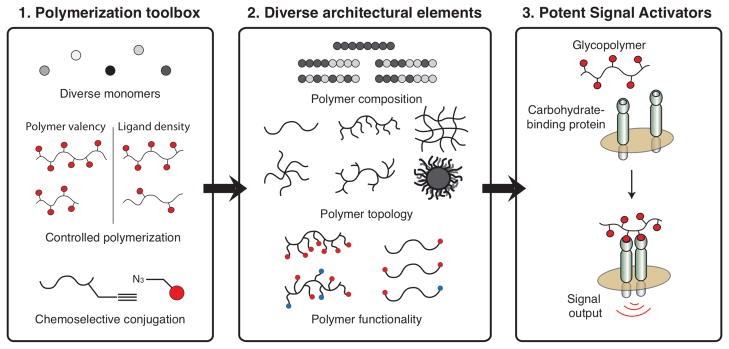

Over the last two decades, many scaffolds have been developed for displaying carbohydrates. These range from dendrimers,35, 36 to oligomeric bioconjugates37, to polymers38–40, to quantum dots41–43 and nanoparticles.44–46 While each scaffold has unique benefits, it is the polymers that can exhibit the greatest variation in valency, individual binding group spacing, and overall architecture. Access to this structural diversity has been made possible by advances in polymer synthesis, which have provided the means not only to synthesize polymers of different structures, but also to control the properties of the polymers that result. By varying the structure of the monomer or the polymerization conditions, a multitude of complex topologies can be accessed (Figure 2).47 Thus, polymers can be generated to carry out systematic investigations into the effect of glycan structure on biological function.

Figure 2.

(Left) Polymers can be assembled from a wide variety of monomers in a controlled manner to generate polymers of a defined length and valency. (Center) The polymers can be generated with many different topologies. In addition, it is possible to generate polymers bearing multiple functionalities, such as biological ligands or fluorophores. (Right) Finally, a key step in eliciting signal transduction is clustering of cell-surface receptors. Polymers bearing carbohydrates can cluster cell-surface proteins to elicit a signaling output. Figure adapted from reference 47.

Despite the benefits of employing glycopolymers to study signal transduction, to date this strategy has been surprisingly underutilized. Given the many new roles for glycans that are being revealed, we hope that this review will stimulate research into carbohydrate-mediated signal transduction. Because signal transduction necessitates robust glycopolymer recognition by protein receptors, we provide an overview of the structural features of glycopolymers that can influence their mechanism of protein recognition. We use these studies to provide some general parameters that might influence the abilities of glycopolymers to affect cell signaling. We also discuss examples of how glycopolymers have been employed to address specific problems in signal transduction. While there are many exciting examples where glycopolymers have been used to elicit an immune response48–54, we highlight those that focus on a specific signal transduction pathway.

2. Maximizing protein recognition of glycopolymers

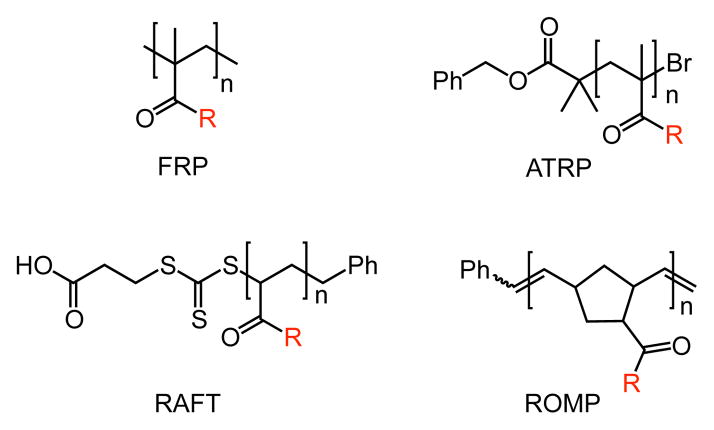

In the 1970s, Lee55 and Horejsí56 described methods for the synthesis of polyacrylamide-based glycopolymers. Their demonstration that these synthetic conjugates could bind lectins spurred investigations using glycopolymers as functional glycan mimics. This led many researchers to explore glycopolymers as potent inhibitors of carbohydrate-binding proteins.57, 58 Accordingly, many polymerization strategies have now been applied to the generation of glycopolymers (Figure 3). The kind of radical polymerization reactions carried out initially (free radical polymerization) have now been complemented by controlled polymerization reactions, such as atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) and reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization (RAFT). Non-radical polymerization strategies also have emerged, including the ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP), which has been used extensively in signaling studies. The synthesis of glycopolymers is beyond the scope of this review, but there many excellent resources on the topic.39, 40, 48, 59, 60

Figure 3.

Example polymer backbones generated from common polymerization strategies used in synthesizing glycopolymers. The R substituent represents a linker bearing a carbohydrate ligand, but for many glycopolymers not every monomer unit bears a carbohydrate ligand.

For glycopolymers to affect signal transduction, they must bind effectively to at least one but often multiple copies of their protein receptor. Using controlled polymerization methods, many aspects of the glycopolymer structure can be altered systematically to optimize its activity. Some key parameters include the length of the polymer, the density of the carbohydrate ligands, the flexibility of the polymer backbone, and the overall structure of the glycopolymer. Thus, glycopolymers can be tailored to inhibit endogenous glycan interactions with a cell surface receptor or to cluster receptors for signaling.39, 61 Previously, we reported general principles for designing multivalent ligands62; subsequent studies have provided additional insight into how glycopolymer features influence activity. Some examples follow that document the interplay between glycopolymer structure and function.

2.1 Glycopolymer length and functional affinity

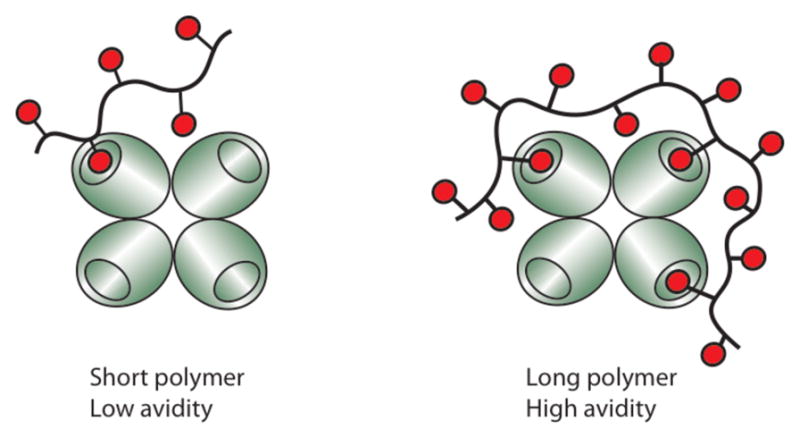

The advent of living polymerization reactions provided a means to alter glycopolymer length. Living polymerizations, in which the rate of elongation is more rapid than termination, are ideal processes for assembling glycopolymers of defined lengths. The separation between binding sites can vary for an oligomeric carbohydrate binding protein, and ligands that can occupy multiple binding sites will have increased functional affinity.63 Glycopolymers of defined lengths can serve as “measuring sticks”; their length (and valency) can be optimized to span multiple binding sites within a carbohydrate-binding protein or between carbohydrate-binding proteins on a cell (Figure 4). For living polymerization reactions with rapid initiation rates, the length of the polymer (degree of polymerization, DP) can be easily predicted and controlled by varying the ratio of initiator to monomer.64–67 In this scenario, an initiator to monomer ratio of 1:100 would afford a 100mer. This strategy of varying polymer length to bridge different lectin binding sites was shown using glycopolymers generated by the ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Specifically, glyopolymer length was optimized to facilitate binding to the tetrameric lectin concanavalin A (Con A).66 The most active glycopolymers were those that could bridge at least two binding sites within the Con A tetramer. Glycosylated dendrimers are another popular scaffold for targeting oligomeric lectins35, 68–72, as different generations or different linkers can be tested to find those that span carbohydrate-binding sites within an oligomeric lectin. To this end, Cloninger and coworkers have employed spin-labels and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy to characterize the spatial distribution of carbohydrates on dendrimers.73, 74

Figure 4.

Increasing polymer length (and valency) allows polymers to span multiple binding sites in oligomeric proteins, thereby increasing their functional affinity (avidity).

2.2 Density of the carbohydrate ligands

Another method to influence glycopolymer functional affinity involves altering the carbohydrate epitope density on a polymer backbone. Studies employing glycopolymer ligands can complement those using natural glycans, whose variation in density can influence their activity.75 With controlled polymerization reactions, the density of the carbohydrate ligand can be manipulated in two ways—copolymerization of a monomer bearing the carbohydrate epitope with a biologically inert monomer, or post-polymerization functionalization of a polymer with the carbohydrate ligand and a biologically inert ligand (Figure 2).76 Using either approach, the overall length of the polymer can be kept constant, while the level of carbohydrate substitution can be varied.

Cairo et al. found that increases in binding epitope density enhanced the ability of multivalent ligands to bind avidly to the lectin Con A.77 The authors used ROMP to generate glycopolymers of various mannose densities by polymerization of different ratios of mannose-substituted monomers and biologically inert galactose-bearing monomers (Con A does not recognize galactose). Their study revealed that as mannose composition increased, both the avidity and the ability of the glycopolymer to cluster Con A increased.

An examination of the role of ligand density at the cellular level was conducted by Rubinstein and coworkers.78 They sought to prepare glycopolymers that could exploit the observed upregulation of the galactose-binding lectin galectin-3 in metastatic tumor cells. They therefore prepared N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) conjugates displaying different levels (10%, 20%, or 30%) of a galactose, galactosamine, lactose, or trivalent galactose derivative. They tested the interaction of these glycopolymers with three different colon cancer cell lines (Colo-205, SW-480, and SW-620).78 The level of galactose substitution influenced binding to some cell lines, but not others. For example, all three glycopolymers bound the SW-480 cell line, while the glycopolymers with the highest substitution levels were the most effective ligands for the Colo-205 cells and SW-620 cells. While the molecular mechanisms underlying these differences have not been determined fully, the results underscore that carbohydrate residue density can be an important parameter in devising effective cell targeting agents.

These aforementioned examples might lead one to conclude that increasing the density of carbohydrate ligands on a polymer always leads to enhanced activity, but such a conclusion would be erroneous. One counter illustration is from Kiick and coworkers, who examined the ability of a series of glycopolymers to inhibit the pentameric cholera toxin (CT),79 a member of the medically important class of AB5 toxins that have been targets for inhibitor design.80–82 Glycopolymers were produced by coupling different mole ratios of an amino galactoside to a poly-glutamic acid backbone. Interestingly, the authors found that the glycopolymer with the lowest level of galactose conjugation was the most effective CT inhibitor. A glycopolymer that consisted entirely of galactose interacted with CT much more weakly. The authors argue that when the density of the galactose moieties decreases, the spacing between the galactose moieties increases, thus approaching the approximate distance between binding sites on CT. Because the activity is reported on a galactose residue basis, galactose residues that do not contribute to protein binding decrease the activity. In a subsequent study, the authors engineered random coiled poly-glutamic acid polymers that were designed to contain galactose moieties spaced apart at specific distances.83 The glycopolymer that had the largest spacing between galactose moieties bound CT with the highest affinity, despite having the lowest valency. Although these glycoconjugates do not yet match the efficacy of the pentavalent glycan ligands devised by the Fan and Bundle groups,80–82 the glycopolymers are quite potent, especially when considering they are unable to occupy all five binding sites within the toxin.

Like the glycopolymer strategy used by Kiick and coworkers, other methods have been developed that allow precise placement of saccharide residues on a polymer backbone, including polypeptides composed of repeating folded domains84, poly(amidoamines)85, and modified nucleic acids.86–91 Hartman and coworkers have devised an iterative approach for assembling polymers with controlled carbohydrate ligand spacing.85 Their strategy entailed the sequential coupling of either an inert ethylenedioxy monomer or an alkynyl monomer that could be functionalized with an azide-bearing mannoside to generate mono-, di-, and tri-mannoside glycopolymers. The spacing between the mannose ligands of the polymers was estimated to be 10 nm for di-mannoside and 7 nm for tri-mannoside. Interestingly, the glycopolymer containing one mannose moiety bound Con A with an IC50 of 8 μM, much lower than that of other monovalent glycan ligands. The authors postulate that the enhanced affinity is due to the highly hydrated ethylenedioxy units on the polymer backbone92–94, but it also possible that the backbone itself contributes to the higher affinity.95 In addition, the authors appended the mannosides to the backbone via a triazole linker, which may also have contributed to the enhanced binding. The glycopolymer that contains two mannose residues with an estimated 10 nm spacing exhibited only a moderate enhancement and was less potent than the monovalent ligand on a saccharide residue basis (IC50 to 5 μM). The glycopolymer with the 7 nm spacing between saccharide residues was designed to be the most effective since it most closely matched the distance between binding sites in Con A (~6.5 nm). Indeed, it was the best ligand (IC50 value of 1 μM) but the modest enhancement observed is not indicative of multivalent binding. Nevertheless, this defined approach could be used to prepare glycopolymers to examine whether carbohydrate spacing affects signal transmission.

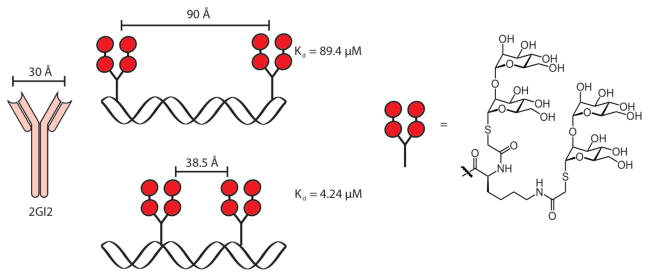

Another means of generating polymer constructs with defined glycan spacing is to use peptide nucleic acid (PNA) backbones.89, 96 For example, multivalent carbohydrate displays of this type have been used to probe how the dimeric antibody 2G12 interacts with mannosylated gp120 on HIV (Figure 5).86 Because 2G12 can neutralize HIV, it is thought that compounds that bind tightly to 2G12 might serve as haptens for the development of effective anti-HIV antibodies. The displays were produced by appending mannose-containing oligosaccharides to a single-stranded PNA and hydridizing the mannosylated PNA to single-stranded DNA strands. The interactions of these assemblies with 2G12 revealed the importance of carbohydrate spacing. The authors used this strategy to generate a potent inhibitor of HIV infection.87 While the synthesis of PNA displays is more labor intensive than assembling glycopolymers by polymerization, the study highlights how the spacing of carbohydrate ligands can be important for generating potent inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) were generated to control the spacing of carbohydrates. The library of PNAs was screened against the dimeric antibody 2GI2, which binds to HIV gp120. As the distance between carbohydrates approached the distance between carbohydrate binding sites on 2GI2, the functional affinity increased.

These examples all serve to illustrate that glycopolymers with the appropriate spacing of carbohydrate ligands exhibit enhanced avidity. The relevance of carbohydrate residue density and spacing in the context of signal transduction are still unexplored. For signaling to occur, multivalent ligands must organize their protein targets into competent signaling complexes. This process typically requires that the multivalent ligand can cluster multiple receptors. The ability to position carbohydrate ligands at defined distances provides the means to test whether different receptor orientations alter signaling. Indeed, data is emerging that suggests it may be important (see, for example, the results of the Kiick Group described in Section 3.1). Still, it seems likely that glycopolymers that activate signaling receptors need only to cluster them. If signaling complex assembly allows for different arrangements of receptors, glycopolymers with a variety of carbohydrate spacings should be capable of activating signaling. For randomly modified glycopolymers, extremely high levels of carbohydrate substitution may sterically block protein binding; consequently, an intermediate density of carbohydrates offers a balance amongst enhancing functional affinity, avoiding unfavorable steric interactions, and presenting carbohydrate ligand arrangement capable of facilitating receptor clustering.10, 11, 97

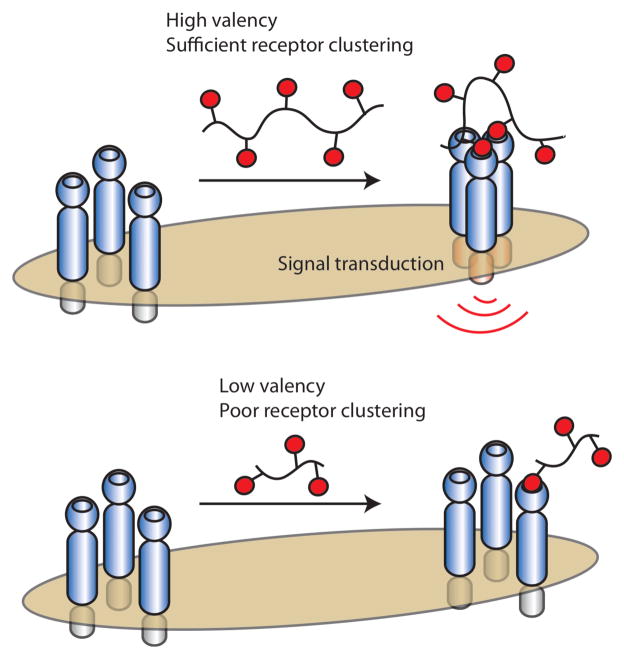

2.3 Glycopolymer length and receptor clustering

The length of a glycopolymer can influence its ability to cluster receptors and how many receptors are in the cluster (Figure 6). Both of these parameters can impact whether a signal is transmitted and how effectively. It has been shown for some glycopolymer scaffolds, that as their length and valency increases, so does the number of receptor copies that they bind.77 This relationship between glycopolymer length and the number of copies of lectin bound could be observed directly using transmission electron microscopy.98

Figure 6.

Polymers of sufficient length are capable of bridging multiple surface receptors, clustering them, and initiating signal transduction.

An example in which longer glycopolymers more effectively transmit signals than do shorter polymers has been described. Bacteria must move towards nutrients and away from toxins for survival.99–101 One attractant for Escherichia coli that promotes chemotaxis is galactose. Signals from galactose are transmitted through the transmembrane chemoreceptor Trg. The chemoreceptors cluster at the poles of the bacteria102, suggesting that they might communicate with each other. Indeed, galactose-substituted polymers of different lengths uncovered the importance of chemoreceptor–chemoreceptor interactions for E. coli responses to attractants. The attractant potency of the glycopolymers depends on their ability to alter the intrinsic organization of the chemoreceptors (e.g., cluster them) in the membrane. Specifically, galactose-substituted polymers of sufficient lengths could induce chemoreceptor clustering. These glycopolymers were more potent attractants than monovalent or oligomeric attractants incapable of mediating receptor clustering.103 Moreover, the galactose-presenting polymers could potentiate responses to other attractants, a result that highlights the ability of the chemoreceptor arrays to act as a kind of sensory organ to detect and integrate signals.104 These studies reveal that glycopolymers can be used to explore the molecular mechanisms critical for signaling. They also highlight that glycopolymer length can influence signal strength. A similar relationship between glycopolymer length and signal transmission was observed in studies using glycopolymers as glycosaminoglycan analogs (vide infra).105, 106

2.4 Flexibility of the polymer backbone

The flexibility of the polymer backbone can also impact a glycopolymer’s ability to bind to protein receptors.62 Initially, one might assume that a rigid polymer with the correct spacing might interact with receptors more tightly, as any multivalent interaction would avoid a conformational entropy penalty. A potential downside of rigid polymers, however, is that they typically are less capable of adapting to protein interfaces; therefore, they will be less apt to adopt a spatial arrangement of glycan residues that complements those of an oligomeric carbohydrate-binding protein (or cluster carbohydrate-binding proteins in a membrane). Indeed, Kobayashi and colleagues noted that rigid glycopolymers often bind weakly to lectins.107 For glycopolymers that present their glycans in a variety of orientations, the backbone rigidity might have little impact on binding.66

Immobilized glycopolymers also have been used to probe the role of polymer rigidity in protein recognition.108 For example, arrays of glycopolymers of varying flexibility were tested for binding to Con A.109 When no cross-linker was added to the polymerization, little interaction with Con A was observed. When a low mole fraction (0.5%) cross-linker was added, the lectin readily bound. When a higher level of cross-linker was employed (1.5%), binding to Con A was reduced significantly. Similarly, Miura investigated Con A binding to glycopolymeric hydrogels of different stiffness.110 They referred to these three states as follows: a flexible swollen state, an intermediate transition state, or a stiff collapsed state. Con A most avidly bound to the transitional hydrogel with intermediate flexibility, the flexible swollen hydrogel was next, with binding to the stiff hydrogel being the weakest.

The flexibility of the linker that connects the carbohydrate to the polymer backbone may also contribute to protein recognition. For example, Stenzel and coworkers generated galactose glycopolymers with either a stiff poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (pHEMA) linker or a flexible polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker.111 The authors investigated the polymers’ ability to inhibit the plant lectin ricin and found the glycopolymers with the flexibile PEG linker were more effective inhibitors. Given the ability of more flexible backbones and linkers to adopt a conformation/orientation that leads to effective interactions, it seems likely that the most active signaling agents will be glycopolymers that maintain this balance and can rapidly and effectively promote protein clustering.10, 11, 33, 34, 103, 106

2.5 Glycopolymer architecture

Advances in controlled polymerization reactions have afforded access to diverse glycopolymer topologies (Figure 2). The role of glycopolymer shape in signal transduction, however, has yet to be explored extensively. A number of studies do suggest that the shape of a multivalent carbohydrate ligand is a critical determinant of its activity. If one considers a carbohydrate-modified surface as “an insoluble glycopolymer”, it is apparent that how glycans are displayed influences their functional affinities and protein binding specificities. One study showed that members of the selectin family bind only weakly to surfaces displaying monovalent sulfated galactose derivatives but avidly to surfaces that present multivalent sulfated galactose glycopolymers.112 The carbohydrate residues were identical, but the multivalent displays had different features. Thus, the manner in which the carbohydrate moiety is displayed can have a marked influence on binding. Differences in glycan presentation have been shown to be important both for implementing glycan array technology and interpreting the data it affords.113 To this end, different methods to fabricate arrays are being examined, from using glycolipids to immobilizing oligosaccharides via short linkers to presenting glycans on surface-linked protein or glycopolymer scaffolds.108, 114–118 These data indicate that the architecture of a glycopolymer will undoubtedly influence its functional affinity for its receptor. Still, functional affinity is just one factor to consider in optimizing glycopolymer signals.

As discussed previously, signal strength can depend upon how many receptors a ligand can recruit to the signaling complex, the orientation of clustered receptors,119 and the rate at which a glycopolymer induces clustering. The link between signal transduction and receptor endocytosis120–122 offers another means by which glycopolymer topology might alter activity. There is growing evidence that the size of a ligand, its shape, and perhaps even whether it is soluble or insoluble all are factors that influence signaling, endocytosis, and trafficking.123, 124 For instance, the dendritic cell lectin Dectin-1 is capable of eliciting an immune response to particulate antigen; however, soluble antigen fails to elicit a response.125

While the field currently is lacking systematic investigation of how the shape of glycopolymers influences their signaling ability, there has been an assessment of how different multivalent carbohydrate ligands influences their mode of interaction with a lectin.77 Gestwicki et al. generated a variety of multivalent mannosylated ligands, including bi- and tri-valent small molecules, globular protein conjugates, dendrimers, linear polymers of controlled lengths, and high molecular weight polydisperse polymers, and evaluated these conjugates in a battery of assays that report on different aspects of their ability to interact with Con A. Compounds were evaluated for their ability to block Con A binding to immobilized glycan, but also many activities relevant for signal transduction: induction of lectin clustering (a quantitative precipitation assay126 that also assessed the stoichiometry of lectin to ligand), the rate of induction of clustering (turbidity assay127), and the distance between receptors in a cluster (fluorescence quenching128). The oligovalent small molecules and dedrimers were not potent inhibitors nor were they able to cluster Con A, suggesting these types of structures might be less effective at eliciting signaling. Alternatively, ligands with high molecular weights, such as the carrier protein conjugates and polydisperse polymers, could bind many copies of Con A; however, fluorescence quenching experiments indicated the bound receptors were not in close proximity to one another. These data suggest that the larger ligands may not be as efficient at eliciting signal transduction. Well-defined glycopolymers efficiently clustered the lectin, and proteins within the cluster were proximal. In another study comparing star polymer scaffolds, significant differences in lectin clustering also were observed. Medium-sized star-polymers were more efficient at clustering the lectin than were large star-polymers.129 Linear glycopolymers, however, were more efficient at interacting with Con A than the star-shaped polymers. Together, the data indicate that ligand architecture can have a profound effect on the mechanism by which a glycopolymer engages its receptor.

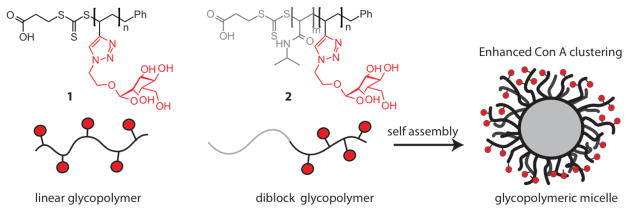

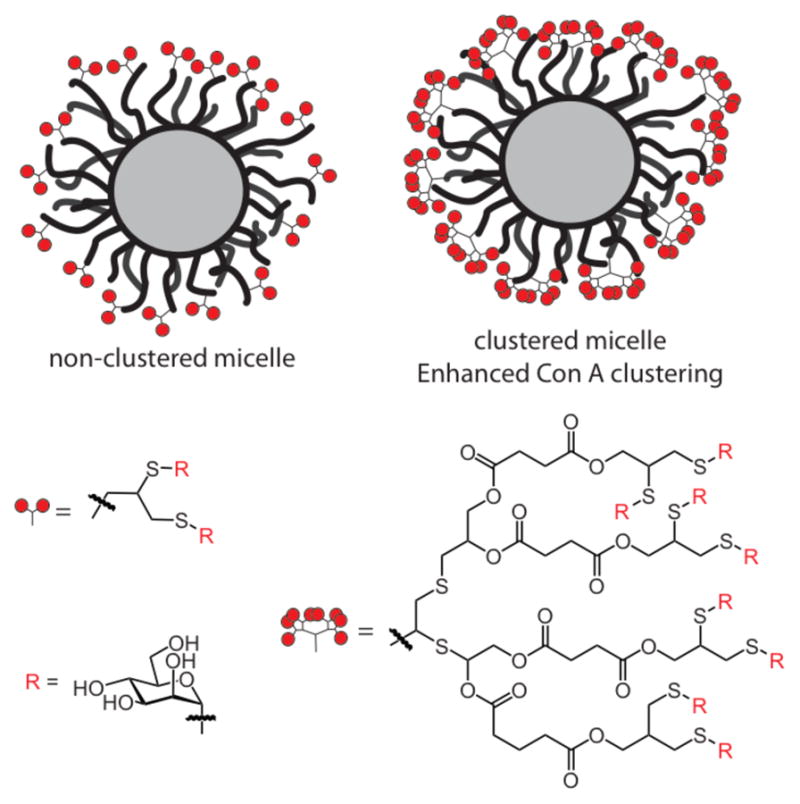

Comparisons between linear glycopolymers, which typically exist as individual entities in solution, and diblock copolymers, which have the propensity to form micelles in solution, have revealed differences in their ability to cluster proteins.130 Contrasting linear glycopolymer 1 (Figure 7) and micelles formed from the assembly of block copolymer 2 was instructive. Con A interacted more strongly with the glycopolymeric micelle than with the linear polymer. Subsequently, the potency of the micelles was augmented by generating block copolymers that display the carbohydrate binding groups in clusters (Figure 8).131.132 As predicted, the clustered glycopolymer-derived micelle was even more effective at clustering Con A.

Figure 7.

Stenzel and coworkers synthesized linear glycopolymers and diblock glycopolymers, which self assembled to form glycopolymeric micelles. The glycopolymeric micelle was more efficient at clustering Con A than the linear glycopolymer.

Figure 8.

An investigation of the role of ligand clustering. Glycopolymers displaying carbohydrate clusters were much more effective at clustering the lectin Con A.

The density of glycopolymer presented by the micelle can be altered by doping in an inert polymer during self-assembly. This strategy was employed by Wooley and colleagues, who utilized ATRP to generated a diblock glycopolymer containing a mannoside moiety at one terminus and a diblock polymer with no functionality on its terminus.133 Mixing various ratios of the two polymers in water resulted in their assembly into micelles with a mannose composition that ranged from 0% to 100%. Increasing the ratio of mannose glycopolymers in the cross-linked micelle increased its ability to block Con A mediated hemaglutinin.

The factors that govern protein recognition by the aforementioned conjugates, including glycopolymeric micelles are complex. The investigations carried out to date on glycopolymeric micelles suggest that they are highly effective at clustering proteins. It seems reasonable, therefore, to postulate that they can be used to deliver powerful signals. Their utility for this purpose, however, has not been investigated. Indeed, many interesting glycopolymer structures have not been tested as signal activators.

3. Mimics of surface glycans

Since all cells present a glycan exterior, it is not surprising that signal transduction can arise from interactions between cell-surface carbohydrate-binding proteins and cell surface-glycans. Glycopolymers have been used to mimic a variety of different types of cell surface glycans, including N-glycoproteins, mucins, and glycosaminoglycans. In this way, glycopolymers can be used to probe how cells communicate with each other or how a pathogen facilitates infection.

3.1 Mimics of mucins

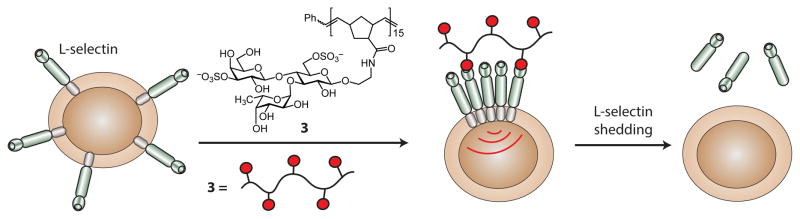

The ability of glycopolymers to mimic mucins53, 134 has been explored extensively in the context of selectin-mediated inflammation. In the inflammatory response, leukocytes are recruited to a site of injury or infection.1, 135, 136 The process involves multiple steps: leukocytes roll across the endothelium; adhere tightly to the endothelium wall; and migrate into the inflamed tissue. In certain disease states, aggressive leukocyte migration is detrimental.137, 138 A key mediator of leukocyte migration is the cell-surface lectin, L-selectin, which interacts with glycoproteins displayed on the endothelium of blood vessels.138, 139 Physiological L-selectin ligands are highly glycosylated mucin-like glycoproteins capped with sialyl Lewis x (sLex) epitopes.140 Because its natural ligand is multivalent, it was postulated that clustering of L-selectin could be important for its function.

A number of different types of glycoproteins were investigated as inhibitors of L-selectin.141–143 Evidence that glycopolymers could cluster this leukocyte surface receptor was obtained using tailored ligands. Using ROMP, a series of different length glycopolymers bearing a 3,6-disulfogalactose ligand and a fluorescent tag were screened for binding to L-selectin-positive cells.144 Because each polymer bore only one fluorescent tag, it was possible to determine the ratio of L-selectin bound to polymer. As the valency of the polymer increased, so did the ratio of L-selectin to polymer, providing evidence that the ligands cluster L-selectin on the cell surface.

Further investigations of L-selectin targeted glycopolymers suggested that they could promote L-selectin-mediated signaling. Specifically, the polymers not only bind to L-selectin but also facilitate its downregulation (Figure 9).145, 146 Treatment of lymphocytes with glycopolymer 3 resulted in a dramatic decrease in cell-surface L-selectin levels. The data indicated that ligand binding triggered the proteolytic release (or shedding) of L-selectin. Consistent with this mechanism, after cells were exposed to the glycopolymers, soluble L-selectin was detected. Monovalent ligands were unable to mediate shedding of L-selectin. The accumulated data suggest that clustering of L-selectin leads to a signal transduction cascade that results in L-selectin shedding.147 Thus, glycopolymers are highly potent inhibitors of L-selectin function through multiple mechanisms: they block interactions of L-selectin with endogenous ligands, promote L-selectin loss from the cell surface, and generate a soluble form of the protein that can inhibit cell surface interactions.

Figure 9.

Glycopolymers were used to promote L-selectin signal transduction. Upon clustering of the surface L-selectin by the glycopolymer, signal transduction occurs that leads to the proteolytic cleavage of L-selectin.

In a subsequent study, Kiick and coworkers investigated the role of carbohydrate-spacing in activating L-selectin shedding.148 Using a polypeptide backbone, sialylated ligands were appended to give a polymer with ligands separated by distances estimated to range from 17 – 35 Å and a polymer with carbohydrate moieties separated by 35 – 50 Å. The polymer with shorter carbohydrate-spacing was more effective at eliciting L-selectin shedding than the polymer with the longer spacing. The diameter of L-selectin is thought to be about 22 Å, which falls in the range of the polymer with shorter carbohydrate-spacing. Still, both polymers should be capable of clustering L-selectin, so the origin of the differences is not obvious. The authors raise the possibility that optimal ligand spacing may be important in eliciting signal transduction.

3.2 Mimics of pathogen glycans

The carbohydrates on the surfaces of pathogens can engage host receptors and activate signaling. Many pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system have evolved to recognized conserved carbohydrate epitopes on the pathogen surface. One key family of PRRs includes the C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), whose members are named for their dependence on calcium ions to facilitate carbohydrate binding.149 Several CLRs are found on dendritic cells (DCs).150 DCs are the major antigen-presenting cells of the immune system, and DC lectins function as antigen receptors, as regulators of DC migration, and as facilitators that mediate binding to other immune cell types.151, 152 The multiple functions of DC lectins contribute to an appropriate immune response.

One CLR of particular interest, DC-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), is a lectin implicated in numerous functions.153, 154 Through interactions with high mannose glycans or fucose-containing Lewis-type antigens on self-glycoproteins ICAM-3 and ICAM-2, DC-SIGN can mediate T cell interactions and trans-endothelial migration.155–157 In addition, DC-SIGN is thought to play a role in pathogen recognition and processing, as anti-DC-SIGN antibodies are internalized, processed and presented to T cells.158 Despite its putative role in healthy immune function, DC-SIGN is exploited by a variety of pathogens, which deploy pathogen-specific mechanisms.159, 160 DC-SIGN binds to the mannosylated envelope glycoprotein gp120 on HIV-1 to mediate infection of T cells in trans.7, 156, 161 Alternatively, binding of DC-SIGN to mannosylated glycoproteins on the surface of Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates signaling pathways that lead to immunosuppression.162 How each pathogen exploits DC-SIGN to take advantage of distinct escape routes remains unclear. Glycopolymers may prove critical tools in understanding the role of antigen structure on DC-SIGN function.

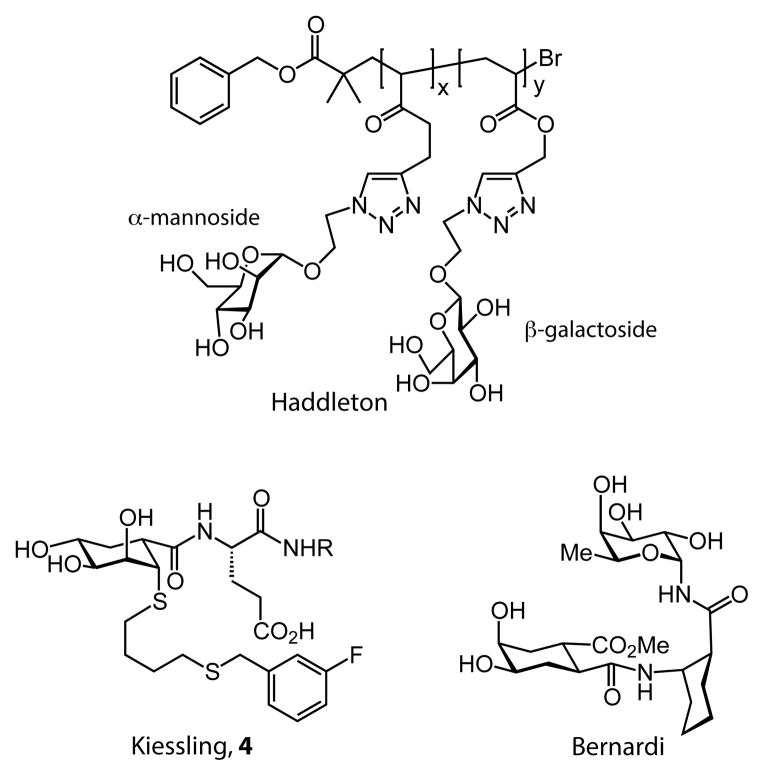

Initial studies of DC-SIGN primarily focused on inhibitors (Figure 10), as inhibitors could block its ability to disseminate viruses, such as HIV.163–166 Haddleton and coworkers, for instance, synthesized mannose-substituted glycopolymers using ATRP.167 They controlled the ratio of a mannoside (DC-SIGN ligand) and galactoside (non-binding) moiety incorporated into the polymers. This strategy of using a non-binding carbohydrate group as a spacer ligand is identical to that employed by Cairo et al. (Section 2.2). As its mannose density increased, so did the ability of the glycopolymers to disrupt the gp120-DC-SIGN interaction. Polymer scaffolds also served as vehicles to present non-carbohydrate glycomimetics (such as 4)168 to DC-SIGN.97 The functional affinity of the glycomimetic was found to be enhanced significantly over that of the monovalent glycomimetic.

Figure 10.

Various inhibitors of DC-SIGN. For compound 4, R=H for a monovalent inhibitor; alternatively, R can be a linker appended to synthetic polymer or protein backbone.

Increasing evidence suggests that the propensity of pathogens to appropriate DC-SIGN arises from the lectin’s ability to participate in signal transduction complexes.169, 170 DC-SIGN also is involved in antigen uptake. It can internalize a variety of synthetic multivalent ligands, including mannose-functionalized gold nanoparticles171, glycoprotein surrogates16, mannosylated dendrimers172, and glycopolymeric nanoparticles173 Whether these synthetic multivalent mannose derivatives promote signaling in dendritic cells is largely unknown.

Data are emerging that implicate DC-SIGN in transducing signaling. Narasimhan and coworkers generated mannosylated polyanhydride nanoparticles that were capable of eliciting DC maturation, a phenomenon that occurs upon interaction with antigen; however, the outcome was not entirely DC-SIGN-dependent.173 Additionally, a study demonstrated that glycopeptidic dendrimers can be internalized by DC-SIGN, activate DC-SIGN signal transduction, and even deliver a peptide antigen for presentation to T cells.70 In general, DC-SIGN signals in collaboration with another class of PRRs, the Toll-like receptors (TLRs).174 TLRs bind to a wide variety of pathogenic epitopes and ultimately results in cytokine production. DC-SIGN stimulation in the presence of TLRs leads to an amplification of TLR-induced cytokine production. One potential means of regulating cytokine production is by controlling the structural features of the DC-SIGN ligand, such as the type of carbohydrate ligand, its valency, or its ability to present other epitopes that promote cross-talk between receptors.170 Glycopolymers and related displays might therefore not only inhibit DC-SIGN but also elicit tailored signals.

There are hints that glycopolymer-promoted DC-SIGN signaling may lead to new insight into DC-SIGN function in immunity and pathogen evasion of the immune system. A recent study by Prost et al. suggests that glycopolymers that bind to DC-SIGN do elicit signaling.16 Specifically, glycoprotein surrogates displaying glycomimetic 4 promote signal transduction. In contrast, Ribeiro-Viana et al. produced mannosylated second-generation glycodendrimers that were internalized by DC-SIGN, but no signaling was detected.172 While neither compound has been assessed for its ability to cluster DC-SIGN, the larger glycoprotein surrogates are likely more capable of mediating DC-SIGN clustering. Thus, the extent of DC-SIGN clustering may determine the level of signal transmission. Forthcoming systematic studies using glycopolymers will undoubtedly aid in understanding how DC-SIGN mediates differential responses to distinct pathogens.

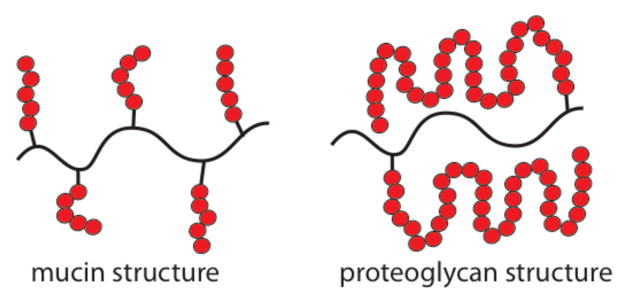

4. Mimics of soluble polysaccharides

Glycopolymers share with glycoproteins (including mucins) a general arrangement in which the glycans emanate from a backbone (either synthetic or proteinaceous) (Figure 11). In contrast, glycosaminoglycans and other polysaccharides are linear carbohydrate chains. Proteins can assemble on these linear polysaccharide chains (e.g., heparan sulfate) to mediate signaling.175, 176 Hsieh-Wilson and coworkers demonstrated that glycopolymers could serve as glycosaminoglycan mimics. Their investigation was prompted by their interest in the role of glycosaminoglycan interactions in axon regrowth. A major barrier in functional recovery after injury to the central nervous system is the inhibitory environment encountered by regenerating axons.177 After recruitment of astrocytes to the injury site, these cells release chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs).178–180 The highly sulfated polysaccharides are the principal inhibitory components of axon regeneration, but their mechanism of action was poorly understood. The consensus was that CSPGs primarily acted as an additional physical barrier to axon regrowth. The function of CSPGs in axon regeneration was elusive because of the complexities associated with GSPG structure. Though studies had suggested distinct roles for specific sulfation patterns in GSPGs, these conclusions rested on experiments conducted using heterogeneous polysaccharides.181–183

Figure 11.

The structure of mucins closely resembles that of glycopolymers. Proteoglycans, however, have a different binding epitope arrangement than that found in glycopolymers. It is a testament to glycopolymer utility that they can function as glycosaminoglycan mimics.

Hsieh-Wilson and colleagues used ROMP to synthesize glycopolymers that served as CSPG mimics.105 They assembled polymers bearing disaccharide and tetrasaccharide sequences derived from the biologically active chondroitin sulfate-E (CS-E) epitope. The ability of the glycopolymers to promote outgrowth of hippocampal neurons was compared to that of a natural CS-E polysaccharide. As expected, the natural CS-E polysaccharide inhibited 100% of neurite outgrowth. Intriguingly, the glycopolymer bearing the tetrasaccharide also inhibited 100% of neurite outgrowth. The activity of the disaccharide-substituted glycopolymer depended on its length—as glycopolymer length increased so neurite outgrowth decreased.

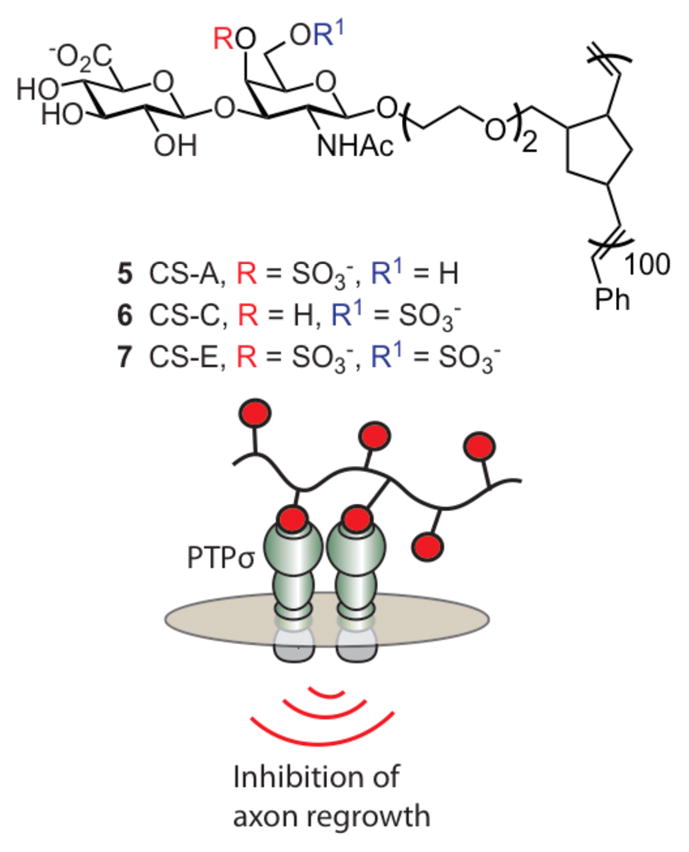

Access to CSPG surrogates allowed for definitive studies on the role of specific CSPG sulfation patterns in axon regeneration. Homoglycopolymers 5 – 7 containing key disaccharides from chondroitin sulfate polysaccharides CS-A, CS-C, or CS-E were synthesis (Figure 12).106 The CSPG mimics were analyzed for inhibition of neurite outgrowth. For comparison, the natural polysaccharides enriched in the three sulfation patterns were tested. Interestingly, only CS-E glycopolymer 7 and the CS-E enriched preparations blocked neurite outgrowth. These data suggest that sulfation at both the 4- and 6-position of N-acetylgalactosamine in CS polysaccharides is required for inhibition.

Figure 12.

Glycopolymers were synthesized by Hsieh-Wilson and coworkers bearing carbohydrate epitopes for CS-A, CS-C, and CS-E. The CS-E glycopolymers were found to inhibit axon regrowth through siganling.

The authors found that CS-E glycopolymer 7 could promote signaling. CSPGs and myelin inhibitors activate Rho/Rho-kinase (ROCK) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathways to impede axon regeneration.184–186 Pharmacological inhibition of ROCK and EGFR with synthetic inhibitors reversed the inhibitory effects of CS-E glycopolymer 7 on the cells. Analogous effects were observed on cells treated with natural polysaccharides enriched with CS-E. The ability of CS-E surrogates to elicit downstream signaling events suggests that they interact directly with a cell-surface receptor. CSPGs can engage protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPs, a glycosaminoglycan binding cell-surface receptor187, 188, and this interaction may be involved in axon regeneration. PTPs was screened in a carbohydrate array and found to interact only with the sulfation pattern present in CS-E polysaccharides. In addition, deletion of PTPs attenuated the inhibitory effects of glycopolymer 7. Therefore, it appears CS-E enriched CSPGs may signal through PTPs to inhibit axon regeneration.

These investigations highlight the power of glycopolymers to act as functional mimics of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. They also underscore the remarkable ability of glycopolymers to mimic a wide range of glycans. Further highlighting that point, antibodies raised against CS-E glycopolymer were specific for the CS-E epitope and had no cross-reactivity with other sulfated glycans.106 These studies highlight the utility of glycopolymers for activating and probing signaling pathways that involve proteoglycans or other polysaccharides.

5. Assembling multireceptor complexes

CD22 is a member of the Siglec (sialic acid binding immunoglobulin-like lectins) family. Siglecs are prevalent on the surfaces of immune cells, where they play key roles in innate and adaptive immunity.189, 190 Glycopolymers have been used to probe how one member of the Siglec class, CD22, leads to attenuation of B cell responses.

Initiation of an immune response and the prevention of autoimmunity is influenced by the ability of the B cell antigen receptor (BCR) to transmit signals that both positively and negatively regulate B lymphocyte survival, proliferation, and differentiation.191 To aid in discriminating between self- and non-self, co-receptors that modulate BCR signaling help ensure these distinctions are made. CD22 is an inhibitory coreceptor that can attenuate BCR signaling.190 Studies in CD22-deficient mice suggest that CD22 acts to increase the threshold for B cell activation.192–194 CD22 recognizes a-(2,6)-linked sialylated glycans195, which are present on some antigens but also abundant on the surface of B cells.195 Cis interactions between CD22 and proximal surface glycans can mask the coreceptor to exogenous (trans) ligands. No binding of even multivalent trisaccharide CD22 ligands was observed, until the cells were treated to remove or disable cell surface sialic acid residues.14, 196–199 Paulson and coworkers, however, generated modified oligosaccharide derivatives with higher affinity for CD22, and multivalent displays of these ligands could out-compete the cis interactions to bind CD22 in trans.14 Data indicate that the functional role of the cis interactions between CD22 and surface glycoproteins is to sequester CD22 from the BCR prior to antigen stimulation.13, 200

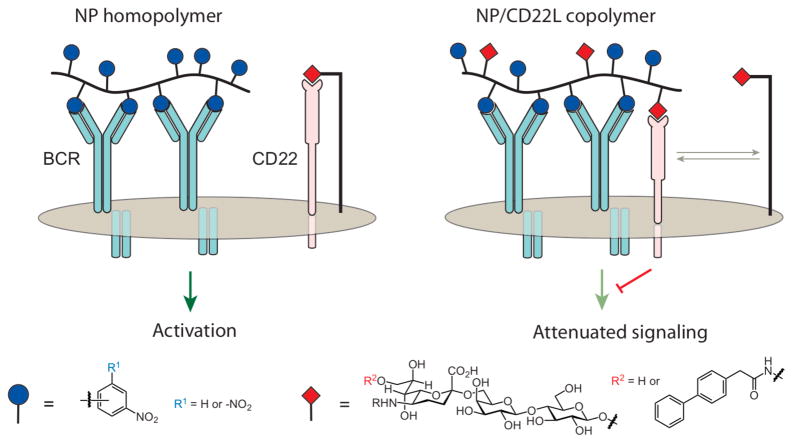

In addition to the importance of cis interactions, evidence had been mounting that trans interactions are important.12,201 A molecular mechanism by which trans interactions alter signaling can be formulated. CD22 possesses cytoplasmic motifs that can recruit a phosphatase to the BCR signaling complex to counteract kinases that lead to B cell activation. If trans interactions are important, antigens that can co-cluster CD22 and the BCR should give rise to attenuated immune activation. Mixed glycopolymers provided an ideal vehicle with which to test this model, both at the level of signal transduction in cells11 and immune suppression in vivo.202

Glycopolymers were used to elucidate a role for trans interactions with CD22 in modulating B cell signaling (Figure 12).198 Glycopolymers were synthesized that display glycan ligands for CD22 (Figure 12, R2 = H) and the 2,4 dinitrophenyl (DNP, R1 = -NO2) hapten that could engage the BCR. DNP-displaying polymers had been shown to elicit activation in a B cell line with a DNP-binding BCR10, and this cell line was used to test whether trans interactions could influence signaling through CD22 (Figure 13).11 Specifically, if only cis CD22 interactions are relevant, CD22 would be masked, and the polymers would interact solely with the BCR to promote B cell activation. In contrast, if the polymers engage both the BCR and CD22 through trans interactions, B-cell activation would be dampened.

Figure 13.

Polymers were designed to contain a nitrophenyl or dinitrophenyl hapten, a carbohydrate ligand for CD22, or both. The hapent-substituted homopolymer only interacts with the B cell receptor complex (BCR), which activates B cell signaling. A copolymer bearing a hapten and a ligand for the lectin CD22 can interact with both the BCR and CD22, which attenuates B cell activation and suppresses immunity.

To determine the outcome, a DNP homopolymer, CD22L homopolymer, and CD22L/DNP copolymer were employed. A hallmark of B cell signaling involves the influx of intracellular Ca2+. If BCR signaling is activated, as with DNP homopolymer10, an influx of Ca2+ should be observed. The CD22L homopolymer did not elicit any change in intracellular Ca2+, consistent with its inability to bind the BCR. If the copolymer could recruit CD22 to the BCR complex, B cell activation should be suppressed and Ca2+ influx should be attenuated. It is that outcome that was observed. These data indicate that co-clustering of CD22 and the BCR results in signal attenuation. These glycopolymers were used further to identify which proteins involved in BCR signaling were activated and which were deactivated upon co-clustering of CD22 and the BCR.

Paulson and coworkers carried out in vivo studies that highlight the role of trans interactions with CD22 for attenuating B cell activation.202 Using a polyacrylamide polymer functionalized with a nitrophenyl hapten (R1 = H) and a high affinity CD22 ligand (R2 = biphenyl), mice were treated with the glycopolymers and their B cell response was measured. The glycopolymers were non-immunogenic, and they promoted long-lived tolerance, preventing B cell responses when the mice were challenged with an immunogen. When mice deficient in CD22 were treated with these polymers, no tolerogenic response was observed. Together, the cell-based and in vivo investigations lead to the importance of trans CD22 interactions. They support a role for antigen glycosylation as an innate form of self-recognition.201

These experiments also demonstrate the utility of using glycopolymers to address mechanistic questions in signaling. Polymer scaffolds can present multiple ligands for multiple receptors. Thus, they are ideal tools to dissect cross-talk between cell surface receptors. Additionally, the glycopolymers described in this section can serve as therapeutic leads for the design of agents that inhibit or suppress autoimmune responses.

6. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Cell surface protein receptors are tasked with the essential role of sensing the cell’s environment and initiating a rapid response to ensure survival. These receptors rarely act as individual entities, but instead work in concert to form highly sensitive, macromolecular signaling assemblies. Glycopolymers that can promote and stabilize these complexes are powerful agents for understanding and exploiting mechanisms of signal transduction. The advent of new polymerization methods that can yield glycopolymers of diverse architecture provides the means to optimize glycopolymers to elicit or inhibit signal transduction. Thus, they can elucidate critical aspects of signal transduction that elude traditional approaches. How glycopolymer topology influences signaling is largely unexplored, and this arena remains an exciting frontier.125, 203–205

Glycopolymers may also prove useful in dissecting the role of oligosaccharides in the assembly of multiprotein supramolecular complexes in signal transduction. In addition to their utility in understanding signal transduction, glycopolymers have possible therapeutic uses.206 Their ability to modulate immune responses may lead to new therapeutic strategies.48–54, 207 For example, the Bundle and Paulson groups described heterobifunctional glycopolymers that template IgM onto the surface of lymphoma cells to elicit humoral cytotoxicity.199 Glycopolymers are also being explored in vaccine development208 and drug delivery.209–212 We hope that this overview will spur new applications of synthetic glycopolymers to explore and exploit diverse signal transduction processes.

Biographies

Laura L. Kiessling holds the Steenbock Chair in Chemistry and is the Laurens Anderson Professor of Biochemistry. She received her B.S. in Chemistry from MIT and her Ph.D. in Chemistry from Yale University with Professor Stuart Schreiber. She was an ACS postdoctoral fellow in Chemical Biology at the California Institute of Technology with Peter Dervan. In 1991, she joined the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is the founding and current Editor-In-Chief of ACS Chemical Biology. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Society for Microbiology, and a Member of the National Academy of Sciences. The Kiessling group is focused on elucidating and exploiting the mechanisms of cell surface recognition processes, especially those involving protein–carbohydrate interactions. Her group interests include understanding how glycans are assembled, elucidating their biological roles, and using this information to co-opt or inhibit glycan interactions.

Joseph Grim was born in Chicago, Illinois. He received his B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Wisconsin—Green Bay in 2008. He then joined the research group of Professor Laura Kiessling at the University of Wisconsin—Madison where he is currently a doctoral candidate. He is designing and synthesizing multivalent glycoconjugates to study the function of C-type lectins in immunity.

Footnotes

Part of the carbohydrate chemistry themed issue.

References and Notes

- 1.Ito S. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1974;268:55–66. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1974.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW, Irvin RT, Cheng KJ. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:299–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröter S, Osterhoff C, McArdle W, Ivell R. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:302–313. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florman HM, Wassarman PM. Cell. 1985;41:313–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang PC, Chiu PCN, Lee CL, Chang LY, Panico M, Morris HR, Haslam SM, Khoo KH, Clark GF, Yeung WSB, Dell A. Science. 2011;333:1761–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.1207438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genbacev OD, Prakobphol A, Foulk RA, Krtolica AR, Ilic D, Singer MS, Yang ZQ, Kiessling LL, Rosen SD, Fisher SJ. Science. 2003;299:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.1079546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. Immunity. 2002;16:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kooyk Yv, Rabinovich GA. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinovich GA, van Kooyk Y, Cobb BA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1253:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puffer EB, Pontrello JK, Hollenbeck JJ, Kink JA, Kiessling LL. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:252–262. doi: 10.1021/cb600489g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courtney AH, Puffer EB, Pontrello JK, Yang ZQ, Kiessling LL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2500–2505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807207106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins BE, Blixt O, DeSieno AR, Bovin N, Marth JD, Paulson JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6104–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400851101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins BE, Smith BA, Bengtson P, Paulson JC. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:199–206. doi: 10.1038/ni1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins BE, Blixt O, Han S, Duong B, Li H, Nathan JK, Bovin N, Paulson JC. J Immunol. 2006;177:2994–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez JD, Baum LG. Glycobiology. 2002;12:127R–136R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prost LR, Grim JC, Tonelli M, Kiessling LL. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1603–1608. doi: 10.1021/cb300260p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiessling LL, Splain RA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:619–653. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.070606.100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weis WI, Drickamer K. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rini JM. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:551–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabius HJ, André S, Jiménez-Barbero J, Romero A, Solís D. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundquist JJ, Toone EJ. Chem Rev. 2002;102:555–578. doi: 10.1021/cr000418f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacchettini JC, Baum LG, Brewer CF. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2001;40:3009–3015. doi: 10.1021/bi002544j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann DA, Kanai M, Maly DJ, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10575–10582. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dam TK, Roy R, Pagé D, Brewer CF. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:1359–1363. doi: 10.1021/bi015829k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page MI, Jencks WP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:1678–1683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiessling LL, Pohl NL. Chem Biol. 1996;3:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee RT, Lee YC. Glycoconj J. 2000;17:543–551. doi: 10.1023/a:1011070425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2755–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mortell KH, Weatherman RV, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2297–2298. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao J, Lahiri J, Isaacs L, Weis RM, Whitesides GM. Science. 1998;280:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perelson AS. Math Biosci. 1981;53:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:696–703. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cloninger MJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:742–748. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röglin L, Lempens EHM, Meijer EW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;50:102–112. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manimala JC, Roach TA, Li Z, Gildersleeve JC. Glycobiology. 2007;17:17C–23C. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becer CR. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2012;33:742–752. doi: 10.1002/marc.201200055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ting SRS, Chen G, Stenzel MH. Polym Chem. 2010;1:1392–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miura Y. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2007;45:5031–5036. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hild WA, Breunig M, Göpferich A. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao X, Wang T, Wu B, Chen J, Chen J, Yue Y, Dai N, Chen H, Jiang X. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kikkeri R, Lepenies B, Adibekian A, Laurino P, Seeberger PH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2110–2112. doi: 10.1021/ja807711w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chien YY, Jan MD, Adak AK, Tzeng HC, Lin YP, Chen YJ, Wang KT, Chen CT, Chen CC, Lin CC. Chem Bio Chem. 2008;9:1100–1109. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song EH, Osanya AO, Petersen CA, Pohl NLB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11428–11430. doi: 10.1021/ja103351m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds M, Marradi M, Imberty A, Penadés S, Pérez S. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:4264–4273. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matyjaszewski K. Science. 2011;333:1104–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1209660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spain SG, Cameron NR. Polym Chem. 2010;2:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy R, Baek MG, Rittenhouse-Olson K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1809–1816. doi: 10.1021/ja002596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baek MG, Roy R. Biorg Med Chem. 2002;10:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hulikova K, Benson V, Svoboda J, Sima P, Fiserova A. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hulikova K, Svoboda J, Benson V, Grobarova V, Fiserova A. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rele SM, Cui W, Wang L, Hou S, Barr-Zarse G, Tatton D, Gnanou Y, Esko JD, Chaikof EL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10132–10133. doi: 10.1021/ja0511974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geng J, Mantovani G, Tao L, Nicolas J, Chen G, Wallis R, Mitchell DA, Johnson BRG, Evans SD, Haddleton DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15156–15163. doi: 10.1021/ja072999x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schnaar RL, Lee YC. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1975;14:1535–1541. doi: 10.1021/bi00678a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horejsí V, Smolek P, Kocourek J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;538:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spaltenstein A, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:686–687. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matrosovich MN, Mochalova LV, Marinina VP, Byramova NE, Bovin NV. FEBS Lett. 1990;272:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ladmiral V, Melia E, Haddleton DM. Eur Polym J. 2004;40:431–449. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vázquez-Dorbatt V, Lee J, Lin EW, Maynard HD. Chem Bio Chem. 2012;13:2478–2487. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deniaud D, Julienne K, Gouin SG. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:966–979. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kiessling LL, Strong LE, Gestwicki JE. Annu Rep Med Chem. 2000;35:321–330. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Braun P, Nägele B, Wittmann V, Drescher M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:8428–8431. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lynn DM, Mohr B, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:1627–1628. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fraser C, Grubbs RH. Macromolecules. 1995;28:7248–7255. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanai M, Mortell KH, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:9931–9932. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lynn DM, Kanaoka S, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:784–790. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roy R. Trends in Glycoscience and Glycotechnology. 2003;15:291–310. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lindhorst TK, Kieburg C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1996;35:1953–1956. [Google Scholar]

- 70.García-Vallejo JJ, Ambrosini M, Overbeek A, van Riel WE, Bloem K, Unger WWJ, Chiodo F, Bolscher JG, Nazmi K, Kalay H, van Kooyk Y. Mol Immunol. 2013;53:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Branderhorst HM, Ruijtenbeek R, Liskamp RMJ, Pieters RJ. Chem Bio Chem. 2008;9:1836–1844. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Euzen R, Reymond JL. Biorg Med Chem. 2011;19:2879–2887. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walter ED, Sebby KB, Usselman RJ, Singel DJ, Cloninger MJ. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:21532–21538. doi: 10.1021/jp0515683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sebby KB, Walter ED, Usselman RJ, Cloninger MJ, Singel DJ. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:4613–4620. doi: 10.1021/jp112390d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dam TK, Brewer CF. Glycobiology. 2010;20:270–279. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burns JA, Gibson MI, Becer CR. Functional Polymers by Post-Polymerization Modification. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2012. pp. 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Strong LE, Oetjen KA, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14922–14933. doi: 10.1021/ja027184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.David A, Kopecková P, Kopeček Ji, Rubinstein A. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1114–1122. doi: 10.1023/a:1019885807067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Polizzotti BD, Kiick KL. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:483–490. doi: 10.1021/bm050672n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kitov PI, Sadowska JM, Mulvey G, Armstrong GD, Ling H, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Bundle DR. Nature. 2000;403:669–672. doi: 10.1038/35001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fan E, Merritt EA, Verlinde CLMJ, Hol WGJ. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:680–686. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fan EK, Zhang ZS, Minke WE, Hou Z, Verlinde C, Hol WGJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2663–2664. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Polizzotti BD, Maheshwari R, Vinkenborg J, Kiick KL. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7103–7110. doi: 10.1021/ma070725o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hollenbeck JJ, Danner DJ, Landgren RM, Rainbolt TK, Roberts DS. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:1996–2002. doi: 10.1021/bm300455f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ponader D, Wojcik F, Beceren-Braun F, Dernedde J, Hartmann L. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:1845–1852. doi: 10.1021/bm300331z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gorska K, Huang KT, Chaloin O, Winssinger N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:7695–7700. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ciobanu M, Huang KT, Daguer JP, Barluenga S, Chaloin O, Schaeffer E, Mueller CG, Mitchell DA, Winssinger N. Chem Commun. 2011;47:9321. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13213j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Englund EA, Wang D, Fujigaki H, Sakai H, Micklitsch CM, Ghirlando R, Martin-Manso G, Pendrak ML, Roberts DD, Durell SR, Appella DH. Nat Commun. 2011;3:614–617. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scheibe C, Wedepohl S, Riese SB, Dernedde J, Seitz O. Chem Bio Chem. 2013;14:236–250. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Das I, Désiré J, Manvar D, Baussanne I, Pandey VN, Décout JL. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6021–6032. doi: 10.1021/jm300253q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Spinelli N, Defrancq E, Morvan F. Chem Soc Rev. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jayaraman N. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3463–3483. doi: 10.1039/b815961k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Clarke C, Woods RJ, Gluska J, Cooper A, Nutley MA, Boons GJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12238–12247. doi: 10.1021/ja004315q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kadirvelraj R, Foley BL, Dyekjær JD, Woods RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16933–16942. doi: 10.1021/ja8039663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sigal GB, Mammen M, Dahmann G, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3789–3800. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schlegel MK, Hütter J, Eriksson M, Lepenies B, Seeberger PH. Chem Bio Chem. 2011;12:2791–2800. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garber KCA, Wangkanont K, Carlson EE, Kiessling LL. Chem Commun. 2010;46:6747–6749. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00830c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gestwicki JE, Strong LE, Kiessling LL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4567–4570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Falke JJ, Bass RB, Butler SL, Chervitz SA, Danielson MA. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:457–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ, Parkinson JS. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adler J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:341–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Maddick JR, Shapiro L. Science. 1993;259:1754–1757. doi: 10.1126/science.8456303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gestwicki JE, Strong LE, Kiessling LL. Chem Biol. 2000;7:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gestwicki JE, Kiessling LL. Nature. 2002;415:81–84. doi: 10.1038/415081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rawat M, Gama CI, Matson JB, Hsieh-Wilson LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2959–2961. doi: 10.1021/ja709993p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brown JM, Xia J, Zhuang B, Cho KS, Rogers CJ, Gama CI, Rawat M, Tully SE, Uetani N, Mason DE, Tremblay ML, Peters EC, Habuchi O, Chen DF, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4768–4773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121318109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hasegawa T, Kondoh S, Matsuura K, Kobayashi K. Macromolecules. 1999;32:6595–6603. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Godula K, Rabuka D, Nam KT, Bertozzi CR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4973–4976. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yu L, Huang M, Wang PG, Zeng X. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8979–8986. doi: 10.1021/ac071453q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoshino Y, Nakamoto M, Miura Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15209–15212. doi: 10.1021/ja306053s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kumar J, McDowall L, Chen G, Stenzel MH. Polym Chem. 2011;2:1879–1886. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Mann DA, Owen RM, Kiessling LL. Anal Biochem. 2002;305:149–155. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Oyelaran O, Gildersleeve JC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rillahan CD, Paulson JC. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:797–823. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-152236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Blixt O, Head S, Mondala T, Scanlan C, Huflejt ME, Alvarez R, Bryan MC, Fazio F, Calarese D, Stevens J, Razi N, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, van Die I, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Cummings R, Bovin N, Wong CH, Paulson JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17033–17038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bochner BS. J Biol Chem. 2004;280:4307–4312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liang PH, Wu CY, Greenberg WA, Wong CH. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Adams EW, Ratner DM, Bokesch HR, McMahon JB, O’Keefe BR, Seeberger PH. Chem Biol. 2004;11:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Biochem J. 2004;377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gratton SEA, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Goodridge HS, Reyes CN, Becker CA, Katsumoto TR, Ma J, Wolf AJ, Bose N, Chan ASH, Magee AS, Danielson ME, Weiss A, Vasilakos JP, Underhill DM. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Khan MI, Mandal DK, Brewer CF. Carbohydr Res. 1991;213:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Easterbrook-Smith SB. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:637–640. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90074-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Matko J, Edidin M. Methods Enzymol. 1997;278:444–462. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)78023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chen Y, Chen G, Stenzel MH. Macromolecules. 2010;43:8109–8114. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hetzer M, Chen G, Barner-Kowollik C, Stenzel MH. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10:119–126. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kumar J, Bousquet A, Stenzel MH. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2011;32:1620–1626. doi: 10.1002/marc.201100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Martin AL, Li B, Gillies ER. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:734–741. doi: 10.1021/ja807220u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Joralemon MJ, Murthy KS, Remsen EE, Becker ML, Wooley KL. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:903–913. doi: 10.1021/bm0344710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Thoma G, Patton JT, Magnani JL, Ernst B, Öhrlein R, Duthaler RO. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5919–5929. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Vestweber D, Blanks JE. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:181–213. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Worthylake RA, Burridge K. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:569–577. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hemmerich S. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rosen SD. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rosen SD, Bertozzi CR. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rosen SD. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:129–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.090501.080131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Spertini O, Cordey AS, Monai N, Giuffrè L, Schapira M. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:523–531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hicks AER, Nolan SL, Ridger VC, Hellewell PG, Normal KE. Blood. 2002;101:3249–3256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Guyer DA, Moore KL, Lynam EB, Schammel CM, Rogelj S, McEver RP, Sklar LA. Blood. 1996;88:2415–2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Owen RM, Gestwicki JE, Young T, Kiessling LL. Org Lett. 2002;4:2293–2296. doi: 10.1021/ol0259239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gordon EJ, Strong LE, Kiessling LL. Biorg Med Chem. 1998;6:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mowery P, Yang ZQ, Gordon EJ, Dwir O, Spencer AG, Alon R, Kiessling LL. Chem Biol. 2004;11:725–732. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Crockett-Torabi E. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu S, Kiick K. Polym Chem. 2011;2:1513. doi: 10.1039/C1PY00063B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Weis WI, Crichlow GV, Murthy HM, Hendrickson WA, Drickamer K. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20678–20686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Steinman RM. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:S53–S60. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y, Adema GJ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nri723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Robinson MJ, Sancho D, Slack EC, LeibundGut-Landmann S, Sousa CRe. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1258–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Geijtenbeek TBH, Engering A, van Kooyk Y. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:921–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Švajger U, Anderluh M, Jeras M, Obermajer N. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1397–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Geijtenbeek TBH, Krooshoop D, Bleijs DA, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GCF, Grabovsky V, Alon R, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:353–357. doi: 10.1038/79815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]