Abstract

Elastin specific medial vascular calcification, termed Monckeberg’s sclerosis has been recognized as a major risk factor for various cardiovascular events. We hypothesize that chelating agents, such as disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) and sodium thiosulfate (STS) might reverse elastin calcification by directly removing calcium (Ca) from calcified tissues into soluble calcium complexes. We assessed the chelating ability of EDTA, DTPA, and STS on removal of calcium from hydroxyapatite (HA) powder, calcified porcine aortic elastin, and calcified human aorta in vitro. We show that both EDTA and DTPA could effectively remove calcium from HA and calcified tissues, while STS was not effective. The tissue architecture was not altered during chelation. In the animal model of aortic elastin-specific calcification, we further show that local periadventitial delivery of EDTA loaded in to poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles regressed elastin specific calcification in the aorta. Collectively, the data indicate that elastin-specific medial vascular calcification could be reversed by chelating agents.

Keywords: Elastin, Demineralization, Calcium, Arteriosclerosis, Chelating complexes

Introduction

Pathological calcification is defined as ectopic deposition of poorly crystalline hydroxyapatite in soft tissues as observed in blood vessels and cardiac valves [1], The two areas of calcification seen in arterial tissues include intimal calcification, detected in atherosclerotic plaque present in the intima, and medial calcification of elastic layers (MAC), detected in patients with diabetes, renal failure, and old age [2]; which is independent of atherosclerosis. Medial calcification, termed as Monckeberg’s sclerosis, mostly occurs along the elastic fibers of the media. Its presence correlates well with risk of cardiovascular events and leg amputation in diabetic patients [3]. Currently no clinical therapy is available to prevent or reverse this type of vascular calcification. Some possible targets to block and regress calcification include local and circulating inhibitors of calcification as well as factors that may ameliorate vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis [2]. Many of these approaches were focused on atherosclerotic calcification. Almost no research has targeted reversing of elastin specific medial calcification[2].

Chelation therapy most often involves the injection of disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), a chemical that binds, or chelate ionic calcium, trace elements and other divalent cations [4]. Chelation therapy has been touted as an effective treatment to reverse vascular calcification; however, it has been controversial with opposing views [5–7]. At present no systemic scientific studies prove that it could reverse cardiovascular calcification [6]. The Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine began in 2003 to determine the safety and effectiveness of EDTA chelation therapy in individuals with coronary artery disease has been finished by 2013. First published results showed that intravenous chelation regimen with EDTA reduced the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes but data was not sufficiently convincing to support the routine use of chelation therapy for treatment of patients who have had an myocardial infarction [8]. Unfortunately, the efficacy of various chelating agents in reversing elastin specific calcification from the peripheral vascular tissue is not studied very well either in vitro or in animal experiments. Here we tested the hypothesis that common chelating agents, such as disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) and sodium thiosulfate (STS) can remove calcium from hydroxyapatite (HA) and calcified tissues without damaging the tissue architecture.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Hydroxyapatite, disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) and sodium thiosulfate (STS), dichloromethane, were all reagent grades and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Polyvinyl alcohol or PVA (M.W. = 15kDa) was purchased from MP Biomedicals Inc. (Solon, OH). Poly(L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) or PLGA (lactide:glycolide=50:50, M.W.=60~80kDa) was a gift from Ortec, Inc. (Piedmont, SC). Stock solutions of EDTA, DTPA and STS with concentration of 1, 5, 10 mg/mL were prepared and stored at room temperature. Five mg/mL EDTA had pH of 4.8 while 5 mg/mL DTPA in 0.1 M NaOH had a pH of 12.2.

Tissues Preparation

In order to study chelation effect on elastin specific calcification, we wanted to avoid effect of cells and other extracellular matrix components. Thus, we obtained pure aortic elastin from porcine aorta with standard methods of purification[10]. We used porcine aorta because of easy access and large quantities of elastin could be obtained. Elastin homology is maintained in all species. In previous study, we showed that when pure aortic elastin is implanted subcutaneously in rats, it undergoes calcification[9]. Thus, this calcified elastin could be used to study demineralization of elastin specific calcification by chelating agents.

Calcified porcine aortic elastin (20 days explanted sample, 160~180 μg Ca/mg tissue) was prepared by subdermal implantation of pure porcine aortic elastin in rats as described previously [9]. Briefly, in juvenile male Sprague-Dawley rats (21 days old, 35 to 40 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) a small incision was made on the back, and two subdermal pouches were formed by blunt dissection. Each rat received two 30- to 40-mg purified elastin implants (one per pouch), which were rehydrated in sterile saline 1 to 2 hours before implantation. The rats were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation after 20 days implantation and the implants were retrieved and stored at −80°C. Calcified human aorta (100~300 μg Ca/mg tissue) was from cadavers (age 49–75, both male and female with moderate or severe atherosclerosis) received from Greenville Hospital System (Greenville, SC) following standard dissection technique. All samples were from the abdominal aorta, just below the renal arteries.

Demineralization of Hydroxyapatite

Five mg of hydroxyapatite powder was suspended in 30 mL solution of chelating agents (STS, EDTA, DTPA respectively, 5 mg/mL, n=3), while the control group included distilled and deionized (DD) water. At frequent intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours), 1 mL of supernatant was withdrawn for Ca assay. Calcium content was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer Model 3030, Norwalk, CT) as described previously [11]. Briefly, each sample (15–40 mg) was hydrolyzed in 1 ml of 6 N HCl in a test tube at 70°C overnight and then the solution was completely evaporated at 70°C with a continuous flow of nitrogen in the tube. The residue in the test tube was dissolved in 1 ml of 0.01 N HCl. The hydrolyzed sample were diluted and analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy with calcium standards.

Demineralization of Calcified Tissues

Calcified porcine aortic elastin and separately calcified human aorta (10 mg each) were treated with 30 mL chelating solutions (5 mg/mL of STS, EDTA, and DTPA, n=3). The control group was treated with DD water both for calcified porcine aortic elastin and calcified human aorta. At certain intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours for porcine elastin and 8, 12, 24, 36, 48 hours for human aorta), 1 mL of solution was withdrawn for calcium assay. Calcium content was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer Model 3030, Norwalk, CT).

Alizarin Red Stain for Calcium

Calcified elastin samples were treated with chelating agents as described previously and were then embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned, and stained for qualitative analysis of calcium with Dahl’s alizarin red stain. Since the calcified porcine aortic elastin sample had more even distribution of calcification, we did the chelation treatment to the bulk calcified elastin first and then made sections and stained the calcium by Dahl’s alizarin red stain. For human aorta sample, since the distribution of calcification was non uniform, we first sectioned samples and located calcification site and then did the chelation treatment as described. Calcified human aorta were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 24 h, processed with an automatic tissue processor (Tissue TEK VIP, Miles Inc., Mishawaka, IN) and 6 μm paraffin sections (n=12 sections per sample) were soaked in chelating solutions (5 mg/mL of STS, EDTA, and DTPA, n=3) respectively for 4 hours. The control group was treated with DD water (n=3). And then the slides were stained for 3 minutes at room temperature with 1% Alizarin red solution, and rinsed with distilled water. Sections were counterstained with 1% light green solution for 10 seconds and rinsed with distilled water and mounted.

Preparation of EDTA-loaded PLGA nanoparticles

EDTA-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles were prepared by double emulsion method [12]. PLGA (200 mg) was dissolved in 2 mL dichloromethane. EDTA (100 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL deionized water. For the control group, no EDTA was used. Water-in-oil (W1/O) emulsion was prepared with an Omni Ruptor 4000 ultrasonic homogenizer by 20 watts for 5 minutes. This prepared primary emulsion was subsequently added to 10 mL of 1 % (w/v) PVA solution and the second emulsion was prepared with homogenizer (20 watts, 5 minutes) to obtain water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) emulsion. The nanoparticles were isolated by solvent evaporation with stirring overnight at room temperature. After threes wash of deionized water, the nanoparticles were lyophilized and stored at 4 °C.

Measurement of loading efficiency and release profile of EDTA in PLGA nanoparticles

5 mg EDTA-loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles were dissolved in 1 mL of dichloromethane and 5 mL distilled water was added and solutions were vortexed for 30 minutes. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes the supernatant were collected and the concentration of EDTA was spectrophotometrically measured at 257 nm [13]. Five (5) mg EDTA-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were enclosed in dialysis units (Slide-A-Lyzer® MINI Dialysis Units. Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and incubated in 30 ml PBS at 37 °C with mild agitation. At determined time intervals 1 ml sample was withdrawn for quantification of EDTA release.

Local EDTA treatment in CaCl2 injury model of vascular calcification

Calcium chloride (CaCl2) injury model was used to create local arterial calcification (abdominal aortic region) in rats [14]. 10 male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (5–6 weeks old) were placed under general anesthesia (2% to 3% isoflurane), and the infrarenal abdominal aorta was exposed and treated periadventitially with 0.20 mol/L CaCl2 by placing CaCl2-soaked sterile cotton gauze on the aorta for 15 minutes. The area was flushed with warm saline and wound site was closed with sutures. Animals were allowed to recover and placed on normal diet. One week after first surgery, the abdominal aorta was re-exposed in order to provide a treatment directly to the aorta. EDTA loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticle pellet (30 mg, n=5), and pure PLGA particle pellet (No EDTA entrapped, n=5) were placed periadventitially. The rats were allowed to recover. After 1 week, rats were euthanized and tissues (aorta) and blood were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Calcium and Phosphorus level were measured as described previously [11].

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Statistical analyses of the data were performed using single-factor analysis of variance. Differences between means were determined using the least significant difference with an αvalue of 0.05. Asterisks in Figures denote statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Results

Chelation of calcium from hydroxyapatite (HA)

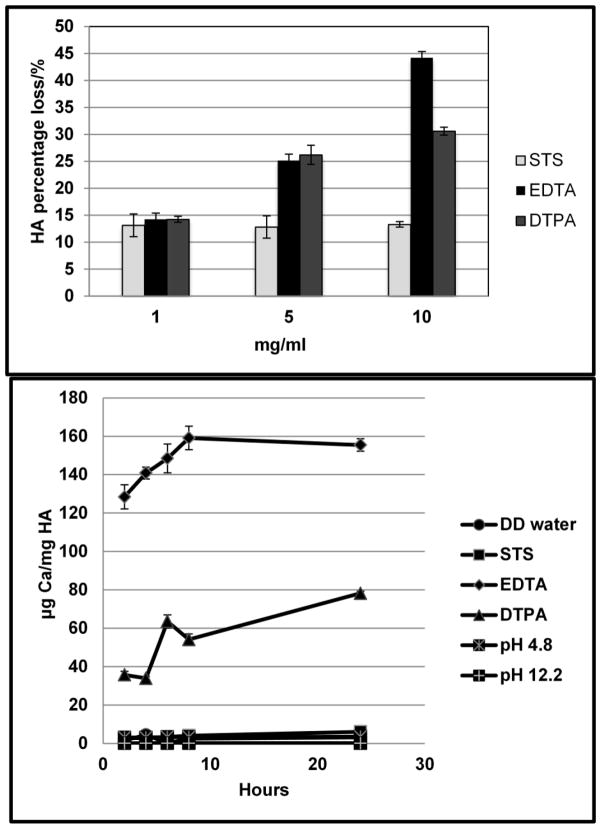

Three series of concentration (1, 5, 10 mg/ml) of chelating agent solutions (STS, EDTA and DTPA) were prepared in order to optimize the concentration needed for efficient demineralization. HA powders (10 mg in each group) were suspended with aqueous chelating agent solutions and the percentage HA solubilization was calculated (Fig. 1a). EDTA & DTPA were stronger chelating agent than STS, and could remove more calcium from HA (Fig. 1a). The chelating capacity was dependent on concentrations of chelating agents with 10 mg/mL showing highest activity. 1 mg STS or EDTA or DTPA chelate 1.3 mg HA, that is, 1 mole of STS, EDTA, DTPA chelate 0.41, 0.88, 1.02 mole of HA respectively.

Fig. 1.

Demineralization of Hydroxyapatite. a: Effect of concentration of chelating agents on dissolving calcium from hydroxyapatite powder. b: Kinetics of demineralization of hydroxyapatite. All data are presented as means ±SEM, n=3 per group.

The concentration of 5 mg/mL of chelating agents were used for further studies [15]. The kinetics of demineralization of hydroxyapatite is shown in Fig. 1b. Most of the chelation and removal of calcium occurred in first 2 hours and continued slowly up to 24 hours for EDTA and DTPA. The chelating ability was: EDTA>DTPA>STS. Since EDTA and DTPA solution as prepared had pH 4.8 and pH 12.2 respectively, we examined the effect of pH on the demineralization of HA. HA was suspended in pH buffers (pH 4.8 buffer: 59.0 mL 0.2M Sodium acetate and 41.0 mL 0.2M acetic acid; pH 12.2 buffer: 50 mL 0.2 M KCl and 20.4mL 0.2 M NaOH). Calcium was not released from HA in the pH range of 4.8 to 12.2 thus suggesting pH did not play a role in calcium chelation. We also neutralized pH to 7.4 for all chelating solutions and still found similar results of chelation (data not shown).

Chelation of calcium from calcified elastin

Calcified aortic elastin (3~5 mg, implanted subdermally in rats to calcify and then isolated) were immersed in 1 mL solution of STS, EDTA, and DTPA with concentrations of 5 and 1 mg/mL for 24 hours under vigorous shaking while the control group was immersed in DD water (n=3 each group). Remnant calcium levels in the treated elastin fiber were measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy. All chelating agents (STS, EDTA and DTPA) could remove calcium from the calcified porcine elastin, with the chelating ability sequence: EDTA ≥DTPA>STS (Fig. 2a). This is consistent to the previous HA results. For the EDTA treatment we calculated the percentage of calcium loss by using the equation: the percentage of calcium loss = (the total calcium in calcified elastin - the remnant calcium in calcified elastin)/the total calcium in calcified elastin*100. Treatment with 1 mg/mL chelating agent for EDTA resulted in about 53 % removal of calcium (Fig. 2a), while higher EDTA concentration (5 mg/mL) was effective in removing 75% of calcium (Fig. 2a). Such increase in calcium dissolution was not found in DTPA and STS groups after increasing chelating agent concentrations (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Demineralization of calcified elastin. a: Optimal concentration of chelating agents needed to remove Ca from calcified elastin. b: Kinetics of demineralization of calcified porcine elastin. All data are presented as means ±SEM, n=3 per group. c: Dahl’s alizarin red stain for porcine elastin after chelation treatments. Alizarin red stains calcium red. Only EDTA treatment removed calcium from calcified elastin.

The kinetics of demineralization of calcifed elastin for chelating agents with the concentration of 5 mg/mL is shown in Fig. 2b (n=3 in each group). Both EDTA and DTPA were effective in removal of calcium from calcified porcine elastin while STS was not effective, which corroborated with the result of hydroxyapatite. However; kinetics of calcium removal from calcified elastin was much slower than HA. Longer incubation times lead to continuous removal of calcium so that within 24 hours EDTA could remove almost all calcium from calcified elastin (Fig. 2b). Dahl’s alizarin red stain at 24 hours of treatment further confirmed that EDTA treatment could remove all calcium while DTPA was partially successful and STS treatment was ineffective (Fig. 2c).

Chelation of calcium from calcified human aorta

The kinetics of extraction of calcium from calcified human aorta after treating with chelating agents for 48 hours, showed that EDTA and DTPA were most effective in removing calcium while STS was not effectively similar to what was observed in HA and elastin studies presented above (Fig. 3a). The kinetics of calcium dissolution was slower probably due to denser nature of aortic tissue. To study tissue architecture after chelation, 6 μm sections of human aorta were treated with chelating solutions for 4 hours. Dahl’s alizarin red stain (Fig. 3b) for the human aorta sections showed that EDTA and DTPA removed the calcium while STS treatment was not effective. The tissue sections maintained their typical arterial integral structure. Chelation treatment did not cause delamination or removal of certain parts of artery for all chelating agents treated group (STS, EDTA, DTPA) comparing to the control group.

Fig. 3.

Demineralization of calcified human aorta. a:Kinetics of demineralizaion of calcified human aorta. All data are presented as means ±SEM, n=3 per group. b: Dahl’s alizarin red stain for human aorta sections after treatment with chelating agents showing efficacy of EDTA and DTPA in removal of calcium.

Reversal of arterial calcification in vivo by EDTA

As EDTA was found to be most successful in removing calcium in vitro, we tested its efficacy in removing calcium from calcified aorta in vivo. We prepared PLGA nanoparticles loaded with EDTA so that prolonged (24 hour) controlled release of EDTA could be achieved when the nanoparticles are placed close to the calcified aorta. Our in vitro release profile showed that EDTA could be released from PLGA nanoparticles within 3 days (Fig. 4). Next, we tested if local delivery of EDTA could remove calcium from calcified rat aorta in vivo. We have shown previously that when abdominal aorta of rats were exposed to chemical injury with calcium chloride, it lead to elastin specific medial arterial calcification with time [16]. We used 7 day time point after injury for EDTA therapy as substantial calcification is seen in this model at that time [15]. After 7 days, EDTA loaded PLGA nanoparticle pellets were placed on the aorta. We observed that the PLGA particles were spontaneously absorbed onto the wet abdominal aorta. Seven days after initial EDTA treatment rats were sacrificed to test if local EDTA therapy would reverse elastin calcification. In vivo studies were continued for 7 days to make sure all of the EDTA could be released and available to remove calcium. Both calcium and phosphorous level were significantly lower in the EDTA treated group as compared the control group with blank nanoparticles (Fig. 5a). Histology analysis also showed that the aortic calcification was greatly reversed in the EDTA treated group (Fig. 5b). The calcium and phosphorus level of the blood plasma in both groups were also quantified and there was no statistical significant difference between the EDTA treated group and pure PLGA control group (Fig. 5c). Clearly suggesting that local delivery of EDTA did not change serum calcium levels, which is often the case with systemic delivery.

Fig. 4.

EDTA release profile from PLGA nanoparticles. All data are presented as means ±SEM, n=3 per group.

Fig. 5.

Reversal of arterial calcification in vivo by EDTA. a: Calcium and phosphorus level of the harvested abdominal aorta after treatment of PLGA particles. Study group: EDTA-loaded PLGA. Control group: PLGA alone. Asterisks in Figures denote statistical significance (P < 0.05) comparing to control group without EDTA entrapped. b: Alizarin Red stains for the harvested aorta treated by EDTA-loaded PLGA particles and control PLGA particles. c: Calcium and phosphorus level of the rats’ plasma after treatment of PLGA particles. There is no statistical significant difference (P>0.05) comparing to control group without EDTA entrapped. All data are presented as means ±SEM, n=5

Discussion

This is the first study to compare three types of chelating agents (STS, EDTA, and DTPA) used for chelation therapy and their chelating efficiency to remove calcium from the hydroxyapatite, calcified aortic porcine elastin and calcified human aorta. We found an optimal concentration (1~10 mg/mL) of chelating agents works very well to remove calcium. Our results indicate that both EDTA and DTPA could effectively remove calcium from hydroxyapatite and calcified tissues, while STS was not effective. The tissue architecture was not altered during chelation. Furthermore, our in vivo study demonstrates the proof of the concept for the first time that local delivery of chelating agents such as EDTA could be used to reverse medial aortic calcification which is found in arteriosclerosis.

Chelating agents’ effectiveness in removing plaques has been advertised and used in certain countries, however, the treatment is not FDA approved in US because lack of substantial conclusive data. The actual published data is very scarce in both animals and human patients and no comparative in vitro or animal studies have been performed to demonstrate the calcium chelating ability of different types of chelating agents (STS, DTPA and EDTA). Pasch et al [17] found that STS could probably chelate calcium by forming soluble calcium thiosulfate complex. They found that it prevents vascular calcification in uremic rats. But systemic treatment of STS also lowered the bone strength in animals probably due to STS chelation of bone HA. They proved direct calcium chelation by STS through a decline of serum ionized calcium concentrations when exposed to STS in vivo and in vitro. Adirekkiat et al[18] demonstrated that STS could remove calcium from precipitated minerals and delayed the progression of coronary artery calcification(CAC) in hemodialysis patients. Patients with a CAC score ≥300 were included to receive intravenous sodium thiosulfate infusion twice weekly post-hemodialysis for 4 months. They found that CAC score did not change significantly in the STS treatment but increased substantially in the control group. Our present study shows that the chelating ability of EDTA and DTPA was superior to STS to remove calcium from hydroxyapatite like mineral from calcified elastic tissue.

Disodium EDTA is an amino acid used to sequester divalent and trivalent metal and mineral ions (e.g., lead, mercury, arsenic, aluminum, cobalt, calcium etc.). EDTA binds to metals via 4 carboxylate and 2 amine groups [19]. Diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) is consisting of a diethylenetriamine backbone with five carboxymethyl groups. The molecule can be viewed as an expanded version of EDTA and it is used similarly for metal chelation. Cavallotti et al [20] found that intravenous injection of EDTA substantially reduced the extent of calcium deposits in the aortic wall. The general decalcifying mechanism of EDTA may derive from its affinity for divalent ions, especially calcium. Maniscalco et al [21] demonstrated that calcification in coronary artery disease could be reversed by EDTA–tetracycline long-term therapy. Their hypothesis was that calcification is caused by nanobacteria (NB). In that study, EDTA was given as a rectal suppository base every evening, which was shown to result in high blood EDTA levels sustained for a long time. They proposed that NB were sensitive in vitro to tetracycline and its action is increased by EDTA dissolving NB apatitic protective coat. Thus, they concluded that combination of these drugs might offer a novel treatment for calcific atherosclerotic disease. EDTA has also been proven to reduce the risk of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder [19] if used as a chelating agent. In that study EDTA was administered through single needle mesotherapy and 15 minutes of pulsed-mode 1 MHz-ultrasound. Calcifications disappeared completely in 62.5% of the patients in the study group and partially in 22.5%; calcifications partially disappeared in only 15% of the patients in the control group, and none displayed a complete disappearance.

Despite these clinical studies and other EDTA chelation therapies that have gone to clinical trials since 2003[22], little basic research is done to study chelation of hydroxyapatite like mineral in vitro and in animal studies. This might be one of the reasons why lots of negative opinions directed toward the chelation therapy for removal of calcium from atherosclerotic plaques. Dr. Jackson[5], the editor of International Journal of Clinical Practice, stated that “Chelation therapy is TACT-less, one wonders why it is still widely used, given the lack of evidence of benefit and potential to do harm (financial gain seems the most likely reason)”. Atwood et al[6] concluded that “…TACT is unethical, dangerous, pointless, and wasteful. It should be abandoned.” Fraker et al[7] concluded that “Chelation therapy (intravenous infusions of ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid or EDTA) is not recommended for the treatment of chronic angina or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and may be harmful because of its potential to cause hypocalcaemia.” First randomized clinical trial results published this year for EDTA chelation therapy for coronary artery disease showed some improvements but the data was not statistically significant to warrant use of chelation therapy for all patients with myocardial infarction [8]. In all clinical studies, chelation therapy was tested to remove calcium from atherosclerotic plaque and improve heart function. Atherosclerotic plaque calcium deposits are due to necrotic tissue core and removal of calcium from plaque may not remove cholesterol laden fatty deposits, thus may not be very effective in reducing heart burden. Some have suggested that calcification make plaques more stable and removal of calcium may make them vulnerable to rupture and that may have led to negative connotations. Our present study with chelating agents is necessary and significant because such therapy was never tested suitably to remove calcium from medial arterial calcification that occurs in absence of atherosclerotic plaques in patients with diabetes, end stage renal disease, and old age. In those cases calcification is observed along the medial elastic layers that make arteries stiff. We envision using chelation therapy for such type of calcification.

Our current results show that both EDTA and DTPA could effectively remove calcium from calcified aortic elastin and calcified human aorta, while STS is not so effective. We have demonstrated that vascular elastin specific calcification could be reversed by chelating agents in vitro. Our in vivo study in the CaCl2 injury model, for the first time, shows proof of the concept that chelating agent loaded PLGA nanoparticles could reverse medial elastin-specific aortic calcification. One criticism of chelation therapy is its effects on serum calcium and bone HA. One previous study of systemic administration of STS in rats showed that such systemic chelation treatment led to the decrease of serum calcium, phosphate and also compromised bone integrity. STS treatment group required significantly lower load to fracture the femurs as compared to controls [15]. Another study in humans also showed that systemic administration of chelation agent caused decrease in serum calcium and serum phosphate levels and caused bone loss by increasing endogenous parathyroid hormone secretion [23]. We consider chelation therapy could be useful in patients with diabetes and old age to remove elastin specific calcification if chelating agents such as EDTA are protected in polymeric capsules (such as nanoparticles) and delivered at the site or targeted to vascular calcification. Such treatment would prevent serum calcium chelation and undesired effect on bone density. Our result in rats study showed such local EDTA treatment with PLGA nanoparticles, completely reversed calcification without damaging vascular structure. This is for the first time anyone has shown effectiveness of local therapy in reversal of calcification. Such local EDTA treatment also did not change serum calcium and phosphorus levels; thus could be used without systemic effects. Our long term goal is to develop site-specific delivery of the chelating agents with targeted nanoparticles to reverse vascular calcification without causing the negative impact on blood chemistry and bone integrity.

Limitations of Our Study

There are some limitations of our current study. Firstly, for in vivo chelation study we did not measure plasma level of other biochemically important metal ions such as chromium, zinc, cobalt, and copper and toxic metals, such as cadmium and lead, which might be affected by the chelation treatment [24]. We used local delivery of small concentrations of EDTA and thus systemic concentrations of chelating agent would be negligible and may not affect other metal ions. Secondly, our animal study results might not be directly applicable to patients with chronic kidney disease or patients on dialysis. In our animal study, the rats had normal kidney function while those patients with arteriosclerosis typically have non-regulated plasma level of calcium, phosphorus and other ions[25]. Finally, we did not look at the bone integrity which might affected by the EDTA treatment. Again, because we used local therapy of EDTA at very low concentrations (4 fold lower than used in clinical trials, per kg basis) instead of systemic delivery, we hypothesize that it will not affect bone integrity.

In conclusion, we did a comparative in vitro study for three types of chelating agents (STS, EDTA and DTPA) and showed that EDTA and DTPA could effectively remove calcium from calcified aortic elastin and calcified human aorta. We, for the first time, show that local EDTA treatment with PLGA nanoparticles could reverse calcification without causing vascular damage and change in the normal plasma level of calcium and phosphorus.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael E. Ward at Greenville hospital system for providing us samples of calcified human aorta and Dr. Tim Cooper at Ortec, Inc. (Piedmont, SC) for gifting the PLGA polymer. This work was partially supported by National Institutes of health (P20GM103444, R01HL061652) and the Hunter Endowment at Clemson University.

List of abbreviations

- EDTA

disodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

- DTPA

diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid

- STS

sodium thiosulfate

- Ca

calcium

- P

phosphorus

- HA

hydroxyapatite

- PLGA

poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- CaCl2

Calcium chloride

- CAC

coronary artery calcification

- MAC

Medial arterial calcification

References

- 1.Liu Y, Zhou YB, Zhang GG, Cai Y, Duan XH, Teng X, Song JQ, Shi Y, Tang CS, Yin XH, Qi YF. Cortistatin attenuates vascular calcification in rats. Regulatory Peptides. 2010;159:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapustin A, Shanahan CM. Targeting vascular calcification: softening-up a hard target. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanahan CM, Cary NRB, Salisbury JR, Proudfoot D, Weissberg PL, Edmonds ME. Medial Localization of Mineralization-Regulating Proteins in Association With Mönckeberg’s Sclerosis: Evidence for Smooth Muscle Cell–Mediated Vascular Calcification. Circulation. 1999;100:2168–2176. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.21.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamas GA, Hussein SJ. EDTA chelation therapy meets evidence-based medicine. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2006;12:213–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson G. Chelation therapy is TACT-less. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2008;62:1821–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atwood KC, Woeckner E, Baratz RS, Sampson WI. Why the NIH Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) should be abandoned. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraker TD, et al. 2007 Chronic Angina Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina. Circulation. 2007;116:2762–2772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamas Ga GCBR, et al. Effect of disodium edta chelation regimen on cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: The tact randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1241–1250. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Basalyga DM, Simionescu A, Isenburg JC, Simionescu DT, Vyavahare NR. Elastin Calcification in the Rat Subdermal Model Is Accompanied by Up-Regulation of Degradative and Osteogenic Cellular Responses. The American Journal of Pathology. 2006;168:490–498. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge S, Keeley F. Arterial Mesenchyme and Arteriosclerosis. Springer; 1974. Age related and atherosclerotic changes in aortic elastin; pp. 173–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vyavahare N, Ogle M, Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Elastin Calcification and its Prevention with Aluminum Chloride Pretreatment. The American Journal of Pathology. 1999;155:973–982. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labhasetwar V, Song C, Levy RJ. Nanoparticle drug delivery system for restenosis. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;24:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cagnasso CE, López LB, Rodríguez VG, Valencia ME. Development and validation of a method for the determination of EDTA in non-alcoholic drinks by HPLC. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2007;20:248–251. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basalyga DM, Simionescu DT, Xiong W, Baxter BT, Starcher BC, Vyavahare NR. Elastin Degradation and Calcification in an Abdominal Aorta Injury Model. Circulation. 2004;110:3480–3487. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148367.08413.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasch A, Schaffner T, Huynh-Do U, Frey BM, Frey FJ, Farese S. Sodium thiosulfate prevents vascular calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1444–1453. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basalyga DM, Simionescu DT, Xiong W, Baxter BT, Starcher BC, Vyavahare NR. Elastin Degradation and Calcification in an Abdominal Aorta Injury Model: Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Circulation. 2004;110:3480–3487. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148367.08413.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasch A, Schaffner T, Huynh-Do U, Frey BM, Frey FJ, Farese S. Sodium thiosulfate prevents vascular calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney International. 2008;74:1444–1453. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adirekkiat S, Sumethkul V, Ingsathit A, Domrongkitchaiporn S, Phakdeekitcharoen B, Kantachuvesiri S, Kitiyakara C, Klyprayong P, Disthabanchong S. Sodium thiosulfate delays the progression of coronary artery calcification in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25:1923–1929. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postnov AA, D’Haese PC, Neven E, Clerck NM, Persy VP. Possibilities and limits of X-ray microtomography for in vivo and ex vivo detection of vascular calcifications. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;25:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavallotti CFMTL, Artico M. Experimental calcification of the aorta in rabbits: Effects of chelating agents and glucagon. Journal of Laboratory Animal Science. 2004;31:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persy V, Postnov A, Neven E, Dams G, De Broe M, D’Haese P, De Clerck N. High-Resolution X-Ray Microtomography Is a Sensitive Method to Detect Vascular Calcification in Living Rats With Chronic Renal Failure. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2006;26:2110–2116. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000236200.02726.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, Mark DB, Rozema T, Nahin RL, Drisko JA, Lee KL. Design of the Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) American Heart Journal. 2012;163:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guldager B, Brixen K, Jørgensen S, Nielsen H, Mosekilde L, Jelnes R. Effects of intravenous EDTA treatment on serum parathyroid hormone (1–84) and biochemical markers of bone turnover. Danish medical bulletin. 1993;40:627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waters RS, Bryden NA, Patterson KY, Veillon C, Anderson RA. EDTA chelation effects on urinary losses of cadmium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, copper, lead, magnesium, and zinc. Biological trace element research. 2001;83:207–221. doi: 10.1385/BTER:83:3:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shroff RC, Shanahan CM. Seminars in dialysis. Wiley Online Library; 2007. Vascular calcification in patients with kidney disease: The vascular biology of calcification; pp. 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]