Summary

Glutamate dehydrogenases (EC 1.4.1.2–4) catalyse the oxidative deamination of l-glutamate to α-ketoglutarate using NAD+ and/or NADP+ as a cofactor. Subunits of homo-hexameric bacterial enzymes comprise a substrate-binding Domain I followed by a nucleotide binding Domain II. The reaction occurs in a catalytic cleft between the two domains. Although conserved residues in the nucleotide-binding domains of various dehydrogenases have been linked to cofactor preferences, the structural basis for specificity in the glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) family remains poorly understood. Here, the refined crystal structure of Escherichia coli GDH in the absence of reactants is described at 2.5Å resolution. Modelling of NADP+ in Domain II reveals the potential contribution of positively charged residues from a neighbouring α-helical hairpin to phosphate recognition. In addition, a serine residue that follows the P7 aspartate is presumed to form a hydrogen bond to the 2’-phosphate. Mutagenesis and kinetic analysis confirms the importance of these residues in NADP+ recognition. Surprisingly, one of the positively charged residues is conserved in all sequences of NAD+ dependent enzymes, but the conformations adopted by the corresponding regions in proteins whose structure has been solved preclude their contribution toward the co-ordination of the 2’-ribose phosphate of NADP+. These studies clarify the sequence/structure relationships in bacterial glutamate dehydrogenases, revealing that identical residues may specify different coenzyme preferences, depending on the structural context. Primary sequence alone is therefore not a reliable guide for predicting coenzyme specificity. We also consider how it is possible for a single sequence to accommodate both coenzymes in the dual specificity GDHs of animals.

Keywords: glutamate dehydrogenase, enzyme catalysis, protein structure, NADP+ specificity, X-ray crystallography

Introduction

Glutamate dehydrogenases (GDHs) play a fundamental role in nitrogen and carbon metabolism. GDH links amino acid metabolism to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle through the conversion of l-glutamate to 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) via oxidative deamination. The inverse reductive amination of 2-oxoglutarate supplies nitrogen for several biosynthetic pathways [1]. GDH belongs to the amino acid dehydrogenase enzyme superfamily whose members display different substrate specificity and have considerable potential in the production of novel non-proteinogenic amino acids for the pharmaceutical industry [2, 3]. Another application of amino acid dehydrogenases is in diagnostics: phenylalanine dehydrogenase for example, has been widely exploited for diagnosis of phenylketonuria [4].

Bacterial and mammalian GDHs are hexameric enzymes that assemble with ‘32’ point group symmetry. Each subunit consists of a largely N-terminal substrate binding ‘Domain I’ that folds into an α/β structure with a central 5-stranded β-sheet, and an NAD(P)+ binding ‘Domain II’ that adopts a modified Rossmann fold [5, 6]. Domain I mediates the majority of inter-subunit contacts along the three-fold and two-fold axes of hexamers. The substrate binding pocket is found in a deep groove at the juxtaposition of the two domains, and there is significant diversity in the relative orientation of Domains I and II in known crystal structures [7]. Sequence identities among the bacterial enzymes so far described vary from 25% to over 90%. The mammalian hexameric enzymes are structurally similar to their bacterial counterparts, except that they have an insertion of an α-helical ‘antenna’ at the three-fold axis that regulates catalytic activity via binding to nucleotide effectors [8]. Several fungal species also contain tetrameric GDHs, but there are no known 3D structures of this class of dehydrogenases, although sequence homology would indicate that their much larger (~115kDa) subunits include the elements of a typical hexameric GDH subunit [9].

Despite their overall structural similarities, microbial GDHs have distinct cofactor preferences. The enzymes can be subdivided into three groups depending on their preference for NAD+, NADP+, or both almost equally [10-12]. Analyses of sequences and structures of other nicotinamide cofactor-dependent enzymes have led to various explanations for the molecular basis of cofactor specificity. The presence of an acidic residue at a position near the 2’ and 3’ OH of adenosine has been reported to offer specific recognition of NAD+ and to discriminate against NADP+ by electrostatic repulsion [13]. This important site, termed the P7 position, has been emphasized along with other residues adjacent to the glycine-rich P-loop (Gly-X-Gly-X-X-Gly/Ala), the so-called ‘finger-print sequence’, for mediating cofactor specificity in the widespread Rossman fold of dehydrogenases [14-16]. The presence of Gly or Ala at P6 reputedly favours binding of NAD+ or NADP+, repsectively.

Historically, the most widely studied bacterial GDH is the Clostridium symbiosum enzyme (CsGDH). However, CsGDH is an exception that violates the fingerprint rules [12, 17], differing in the residue at P6 (Ala) and P7 (Gly) despite rigorous (20,000-fold) NAD+ discrimination over NADP+ [18]. In marked contrast, our recent structure of another bacterial NAD+-dependent GDH, that of Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus (PaGDH), reveals a pattern much more in keeping with the conventional view described above; a glutamate at the P7 position (Glu243) hydrogen bonds to 2’OH and 3’OH of the adenosine ribose facilitated by other residues in the vicinity that allow close approach to the sugar [19]. The comparison of these two structures thus bears out the view that a single enzyme family may offer strikingly different ways of achieving the same specificity. Therefore, cofactor specificity is a complex phenomenon that cannot be extrapolated from sequence motifs alone.

NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli has, like PaGDH, an acidic residue at P7 (Asp263), which would not seem ideal in the adenosine phosphate binding pocket, although it is conserved in other NADP+-specific GDHs. Successful crystallization of E.coli GDH (EcGDH) was initially reported almost 20 years ago [20]. Also, in the course of completing our investigations reported here, a low-resolution structure of EcGDH (3.2Å), determined using high-throughput proteomics techniques of the native source protein, was deposited in the Protein Data Bank ([21]: PDB code 3sbo). Here, we report the refined structure of the free enzyme at 2.5Å resolution. In this structure, wild-type EcGDH has a closed catalytic cleft even in the absence of substrate and cofactor, which is unprecedented for the bacterial GDH family. Modeling of NADP+ in Domain II reveals the presence of three Lys/Arg residues in the vicinity of the 2’-phosphate of the adenosine ribose, and mutagenesis of these residues has confirmed their role in coenzyme binding. Despite the apparent sequence conservation of one of these positively charged residues in both NAD+ and NADP+ enzymes, we observe that it is the context and spatial orientation of the α11-α12 hairpin, where these residues are located, that dictates NADP+ specificity.

Results

Overall architecture of EcGDH and the closed conformation

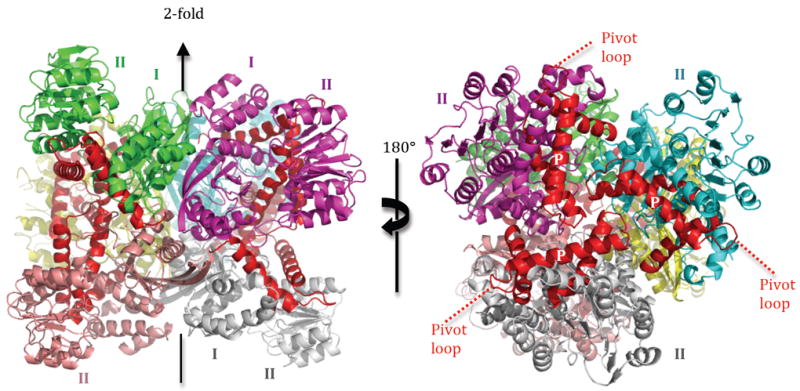

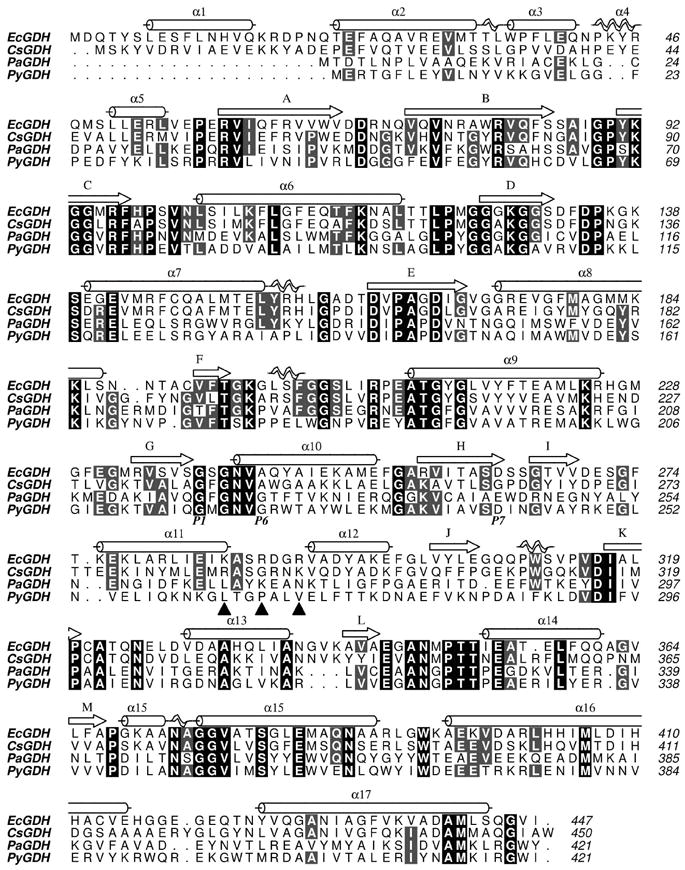

The free enzyme form of EcGDH is a hexamer with 32 symmetry, an assembly that is common to all mammalian and bacterial enzymes (Fig. 1). Domains I and II of each protomer fold with a central mixed β-sheet connected by α-helices, with Domain II adopting a modified Rossmann nucleotide-binding fold. Domain I, which mediates the 32 symmetry contacts and is responsible for substrate binding, comprises residues 1-203 and 425-447. Domain II (residues 204-424) is responsible for cofactor binding, as recently confirmed by the construction of an active chimaeric enzyme comprising Domain I of CsGDH and Domain II of EcGDH and exhibiting NADP+ specificity [22]. EcGDH and CsGDH contain an extra α-helix (α1) at the N-terminus relative to other bacterial enzymes such as PaGDH (Fig. 2). In addition, helices α2/α3 can be considered a single curved helix, rather than two distinct α-helices. However, in order to avoid confusion, the nomenclature used for the secondary structure assignment corresponds to the original CsGDH structure [5]. The final model (chains A-F) fits quite well in electron density maps, with only a small fraction (1.48%) lying outside favourable Ramachandran space. One exception is Domain II (210-360) in chain D, which contains poorly-defined (222-234, 268-274) and disordered (315-319) regions. The quality of the structures is shown with an electron density map (Fig. S1).

Figure 1. Assembly of E.coli glutamate dehydrogenase into the biological hexamer.

Left, view of the 2-fold axis along a horizontal line. Right, view of the 3-fold axis in the line of sight. The three final α-helices of the enzyme (α15-α17) are coloured red, and the pivot helix is identified by the ‘P’ mark (white label) on the right panel. The N-terminal segment of the pivot helix lies near the center of the 3-fold axis.

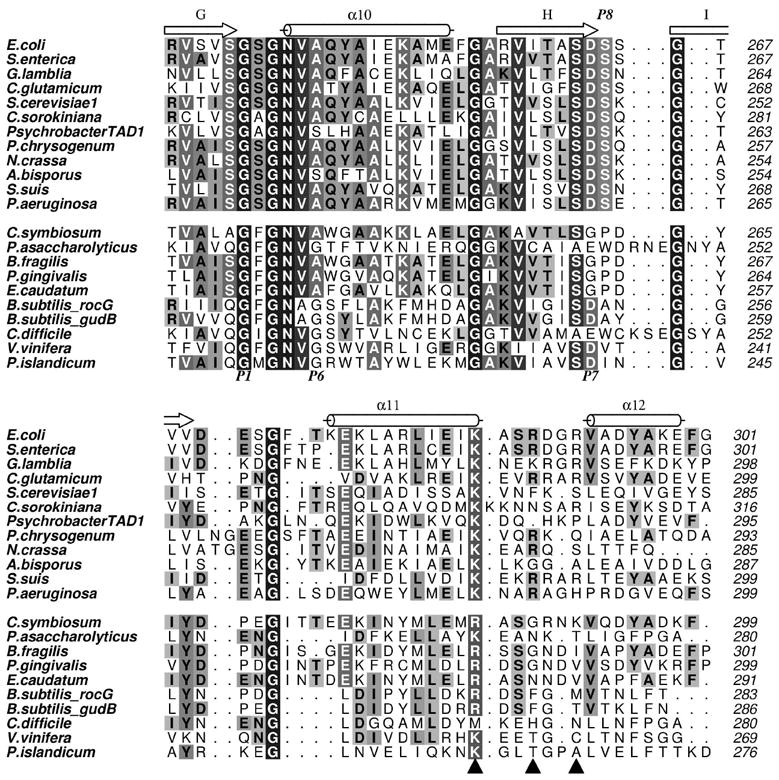

Figure 2. Sequence alignment of bacterial glutamate dehydrogenases.

Secondary structure elements corresponding to EcGDH are shown above the sequence. The three triangles mark the trio of positively charged amino acids that are poised for recognizing the 2’-phosphate of NADP+. The P1, P6 and P7 residues are annotated below the sequences.

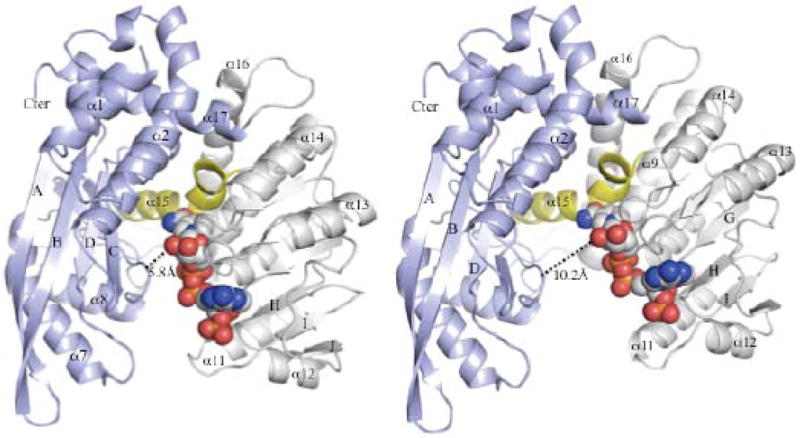

Analysis of the cleft between Domains I and II reveals that 5/6 protomers (chains A-E) are in a relatively closed conformation. The degree of closure is roughly demonstrated by modeling the cofactor in Domain II, and measuring its closest approach to Domain I (Fig. 3). Protomer F (EcGDH-F) is the only molecule in the hexamer that adopts an open conformation that is sufficiently wide for diffusion of both substrate and cofactor. In contrast to EcGDH, the structures of all other wild-type GDHs in the substrate-free state have an open conformation [5, 7, 19, 23]. The distance between the basic residue (Lys136) in Domain I and the 2’-phosphate in the model of EcGDH/NADP+ is only 7.6Å (not shown). Although the conformation of EcGDH is clearly not fully closed, as compared with the bovine GDH (BvGDH)-NADP+ complex [24], the cleft is sterically inaccessible to both the cofactor and the substrate.

Figure 3. Closed conformation of EcGDH.

The N- and C-terminal domains of EcGDH are coloured blue and grey, respectively. NADP+ is shown at the active site in space-filling models. The pivot helix (α15), which binds to substrate and mediates inter-domain motion, is coloured yellow. Domain closure is exemplified by EcGDH-A (left), while EcGDH-F (right) is the only protomer in the open conformation. The measured distance corresponds to Asp168 (Cα) and the 2’-OH group of nicotinamide ribose in the two models of the NADP+/EcGDH complex.

Previous work on the structure of the K89L mutant of CsGDH revealed domain closure even in the absence of substrate [7]. However, it was unclear whether domain closure is enabled by the K89L mutation, since it abrogates a positive charge at the interface of the two domains. The structure of wild-type EcGDH reveals that domain closure is a property of the free enzyme in the absence of substrate and cofactor. The functional consequences of a closed conformation of EcGDH prior to catalysis require further investigation. It would be speculative to correlate the crystalline state directly with the solution state of the enzyme. Furthermore, the effects on catalytic turnover would depend on the timescale of opening/closing, and the rate-limiting step in the reaction, neither of which have been well defined for the bacterial enzymes.

Cofactor specificity in EcGDH

The structure of NADP+-dependent EcGDH and its comparison to previously published NAD+-dependent enzymes provides insight into the molecular basis for cofactor specificity. Structural determinants can be extrapolated from molecular modeling since Domain II acts as a rigid body and appears to maintain most of the secondary and tertiary structural elements required for cofactor binding. Currently, there is no published structure of a bacterial GDH in complex with NADP+. Successful soaking of NAD+ into the active site of CsGDH has been reported previously [5]. Interpretable electron density was seen for 1/3 molecules in the asymmetric unit, and binding was accompanied by subtle side chain rotations. An archaeal GDH from Pyrobaculum islandicum (PiGDH, PDB code 1v9l) in complex with NAD+ remains the only published structure of a non-mammalian GDH with its cofactor for which the co-ordinates are available in the Protein Data Bank [25].

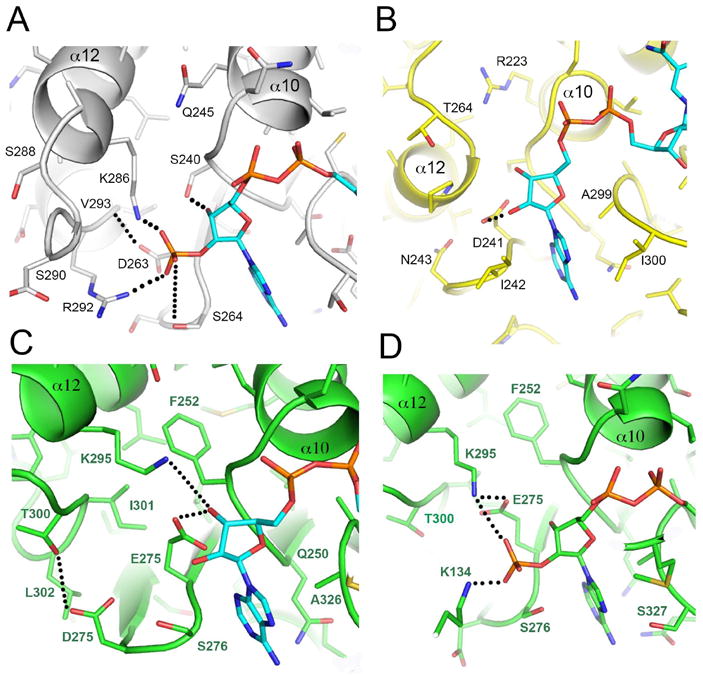

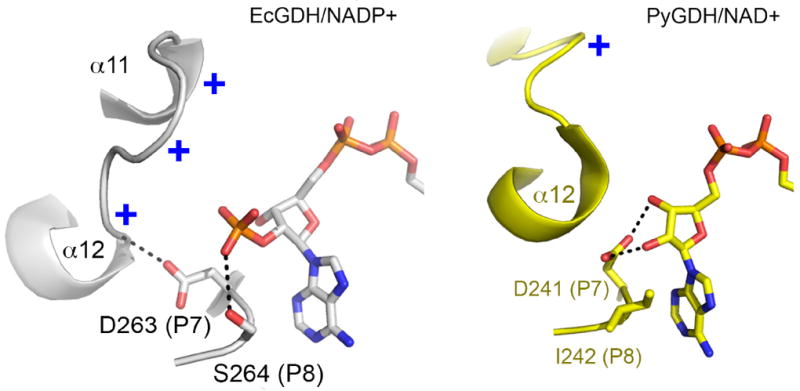

In the absence of a bacterial GDH/NADP+ complex, the cofactor was modeled at the active site by superimposing the bovine structure (1hwz) with Domain II of EcGDH (see Materials and Methods). Docking of the cofactor onto EcGDH-A reveals complementarity to a substantial part of the cofactor pocket in Domain II (Fig. 4). The specificity of EcGDH arises from a combination of sequence and conformational determinants that are evident from molecular modeling of NADP+ onto the free enzyme structure. Three positively-charged amino acids – Lys286, Arg289 and Arg292 – are in the vicinity of the 2’-phosphate and would be available for electrostatic interactions with minor conformational adjustments (Fig. 4). Lys286 and Arg292 are within 2.0Å and 2.8Å of the phosphate, respectively, while the Cα atom of Arg289 is 10.2Å away. Following superposition, no subsequent energy minimisation or rigid-body docking was performed in our modeling. Therefore, small changes in the backbone/side chain conformations would be sufficient to optimize Lys286 contacts with the negatively charged phosphate in the EcGDH/NADP+ complex. With respect to the more distant Arg289, selection of an alternate side-chain conformer results in a distance of only 4.2Å between the guanidino group and the 2’-phosphate of adenine ribose. Enabling all of these potentially favorable electrostatic contacts is the position of ‘α11-loop-α12’, which contributes the basic residues. The side chain of Asp263 (the “P7” residue of EcGDH) from βH points directly at the α-helical dipole of α12 (Fig. 4), which aids in the proper alignment of α11/α12 toward the recognition of NADP+ over NAD+. In fact, the side chain of Asp263 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH of Val293 (3.0Å). This aspartate is the equivalent of Glu243 in PaGDH (P7 position). In PaGDH, the glutamate forms hydrogen bonds with the 2’OH and 3’OH of adenine ribose, thus pointing in a completely different direction [19]. The subsequent residue Ser264, which we propose to designate P8, makes a hydrogen bond to the 2’-phosphate of NADP+ (3.4Å). A serine in this position is conserved in all bacterial NADP+-dependent enzymes. In EcGDH, the P-loop also contributes a hydrogen bond via Ser240(Oγ), which is within 2.1Å of the 3’OH of the ribose.

Figure 4. Structural basis for NADP+ specificity of EcGDH.

Panel A: three basic residues and Ser264 are adjacent to the 2’-phosphate of NADP+ and contribute to cofactor specificity in EcGDH. Panel B: view of the equivalent region in PiGDH, which lacks the basic motif. The P7 acidic residue (Asp241) hydrogen bonds with 2’ and 3’ hydroxyl groups of adenine ribose. Adenine binding is dominated by hydrophobic residues in PiGDH (Ile242, Ile300). The equivalent residues in EcGDH are more polar (Ser264, Thr323). Panels C and D: BvGDH binding to NAD+ and NADP+, respectively. The orientation is similar, but the active site is zoomed out in the BvGDH/NADP+ complex to show Lys134 (Domain I) interactions with the 2’-phosphate. PDB codes are 4bht (EcGDH, Panel A), 2yfq (PaGDH, Panel B), 1hwy (BvGDH, Panel C), and 1hwz (BvGDH, Panel D). In panels A and B, the cofactor was modeled into the unperturbed active site of the enzymes, which were crystallized in the absence of reactants. No energy minimization was performed. Panels C and D are crystal structures of enzyme/cofactor complexes.

Furthermore, the P8 serine which we show is critical for NADP+ recognition in EcGDH is a tryptophan in PaGDH, and thus incapable of partnering the proximal lysine of PaGDH even if it were close enough to interact with the extra phosphate of NADP+. In dual-specific BvGDH, the side chain of the P8 serine (Ser276) interacts with Glu275 as part of a hydrogen bonding network involving the proximal lysine and the 2 OH groups of the ribose when NADH is bound (PDB code 3mw9). The side chain of Ser276 is rotated so that it can H-bond with the extra phosphate group in the NADPH complex (1hwz). Without this rotation, it would sterically interfere with the binding (being 1.0Å from the position of the incoming phosphate). In this structure (1hwz), Glu275 has moved away to allow room for the incoming phosphate, such that it can now only H-bond with the 3’-OH. It also recruits the proximal lysine (Lys295), bringing it 0.5Å closer to the ribose, thus enabling electrostatic interactions with the phosphate of NADPH.

In NAD+-dependent CsGDH, the P7 residue is Gly262, and the loop connecting βH/βI is much closer to the cofactor (relative to EcGDH) so that Pro263 stacks against the adenine ring (not shown). The P7 residue in BvGDH, which has dual specificity, plays two distinct roles in complexes with cofactor (Fig. 4). In the NADP+/BvGDH complex, Glu275 forms a salt bridge to Lys295, which in turn binds to the 2’-phosphate of adenine ribose. In the NAD+/BvGDH complex, alternate side chain conformations enable hydrogen bonds from Glu275 to the 2’ and 3’-hydroxyls of adenine ribose.

Mutagenesis and kinetics studies

Modeling of NADP+ at the active site of EcGDH suggested that a trio of positively charged amino acids may stabilize the negative charge of the 2’-phosphate. Therefore, these residues were subjected to single and multi-site mutagenesis to glutamine residues and assayed for enzyme activity. Mutation to glutamine retains hydrogen-bonding potential of the side chain and provides a critical assessment of the contribution of electrostatic complementarity to NADP+ recognition. The data reveal that the single site mutants are compromised in their catalytic ability (Table 1). As would be expected from disruption of charge complementarity, the apparent Km values are increased to varying extents in the single mutants, but the corresponding kcat is not adversely affected. The most severe effect is in mutant K286Q, which has a 7-fold increase in Km. This is consistent with the structural data, since Lys286 is proximal to the 2’-phosphate and pre-configured to bind the cofactor. The triple mutant (K286Q/R289Q/R292Q) shows a dramatic 50-fold increase in Km. The magnitude of the change highlights the critical role of these basic residues in charge complementarity with the cofactor.

Table 1.

Apparent kinetic parameters for NAD+- and NADP+-dependent catalysis by WT and various mutant EcGDH proteins.

| WT | K286Q | R289Q | R292Q | K286Q | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K286Q | K286Q | R289Q | ||||||

| R289Q | R289Q | R292Q | ||||||

| R292Q | R292Q | S264L | ||||||

| S264L | S240A | |||||||

| NADP+ | Km | *18.4 ± 0.8 | 129 ± 3.2 | *32.8 ± 1.7 | *81.9 ± 3.9 | 929 ± 42 | 19060 ± 1472 | 18300 ± 1676 |

| kcat | 37.3 ± 0.5 | 34.2 ± 0.3 | 37.6 ± 0.6 | 47.3 ± 0.8 | 24.0 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | |

| kcat/Km | 2.03 | 2.65 × 10-1 | 1.15 | 5.78 × 10-1 | 2.58 × 10-2 | 1.31 × 10-4 | 3.77 × 10-4 | |

| NAD+ | Km | 21680 ± 1633 | - | - | - | 24190 ± 3024 | 19480 ± 2974 | 13740 ± 1826 |

| kcat | 2.2 ± 0.1 | - | - | - | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | |

| kcat/Km | 1.02 × 10-4 | - | - | - | 1.61 × 10-4 | 1.18 × 10-4 | 2.48 × 10-4 |

Experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Units of Km are μM, and of kcat are s-1.

Figures marked with an asterisk are S0.5 values, as these enzymes display an apparent mild negative cooperativity towards NADP+ with Hill coefficients varying from 0.89-0.94. Dashes (-) indicate that these parameters were not measured for these enzymes.

In addition to the basic residues in the α11/α12 loop region, the protein sequence alignment shown in Figure 5 reveals a serine residue (Ser264 in EcGDH) that is conserved in all NADP+-dependent GDHs, while it is absent from all of the NAD+-dependent GDHs. As previously mentioned, this P8 serine immediately follows the P7 aspartate, and participates in the recognition of the extra phosphate group of NADP+ in concert with the positively-charged residue(s) present in the α11/α12 loop. Accordingly, we mutated this residue to leucine in order to evaluate its contribution to NADP+ binding. A non-polar residue at P8 is observed in NAD+-utilising enzymes, although the extent of hydrophobicity varies significantly (Fig. 5). None of these changes significantly improve or alter the activity of EcGDH with NAD+; the Km remains high and kcat is unaffected with respect to the wild-type enzyme, resulting in catalytic efficiencies that are practically identical to those of the wild-type enzyme for NAD+ (Table 1). Strikingly, the Ser→Leu mutation has a major bearing on catalysis with NADP+, resulting in an almost 200-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency with this coenzyme, on top of the ca. 80-fold decrease effected by the removal of positive charges in the triple mutant. This confirms that the spatial disposition and composition of these residues is specifically adapted to NADP+. Further mutagenesis of Ser240 (P2 residue), generally conserved in NADP+ GDH (Fig. 5), reveals no additional effects on top of the quadruple mutant (Table 1). Ser240 forms a hydrogen bond to the 3’-OH group of adenine ribose, and would be expected to destabilize binding to both NAD+ and NADP+. Altogether, the kinetic analysis of these mutant enzymes reveals that the positively charged residues in the α11/α12 loop, together with P8-Ser, account for the NADP+ specificity in EcGDH.

Figure 5. Sequence alignment of cofactor-binding segments of bacterial GDHs.

Sequences of NADP+-dependent enzymes are above, while the NAD+-dependent enzymes are grouped below, separated by a space. The P1, P6 and P7 sites are annotated below the alignment, while the P8 position is shown above the alignment. Filled triangles indicate the positively charged residues in EcGDH (α-helical hairpin) that contribute to NADP+ recognition.

Discussion

Model for cofactor preferences

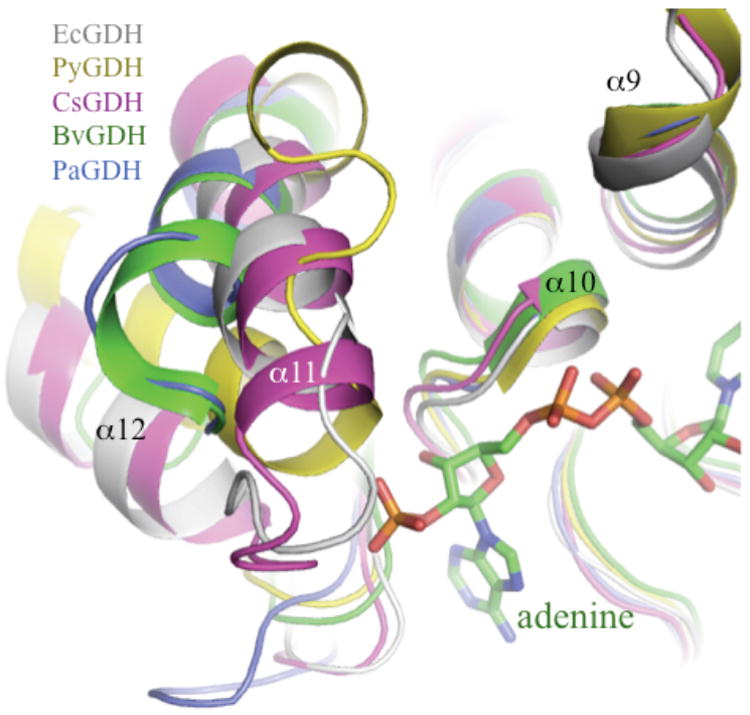

The structural, kinetic, and modeling studies reveal a novel role for the acidic P7 residue in EcGDH. In PiGDH and PaGDH, an acidic P7 residue makes hydrogen bonds to the sugar moiety (adenine ribose), but in models of the NADP+/EcGDH complex, the side chain of Asp263 points toward the α11-loop-α12 region and forms a backbone H-bond with Val293 (NH). The interaction aids in positioning of the ‘α11-loop–α12’ motif, thus orienting positively charged residues (Lys286, Arg289, Arg292) toward the 2’-phosphate of NADP+. Surprisingly, three positively-charged residues are also found in the α11-loop–α12 region of NAD+-dependent clostridial GDH (Fig. 5). The first positively-charged residue is conserved in nearly all NAD+-dependent GDHs. In principle, these enzymes appear to have part of the 2’-phosphate recognition site, although they lack the P8 serine. However, the equivalent of Lys286 (EcGDH) is Arg286 in CsGDH, which makes a salt bridge to the pyrophosphate group of NAD+. The other two basic residues in CsGDH (R290, K292) are facing in completely the opposite way relative to NAD+, and it is difficult to imagine a re-arrangement that would guide them toward the adenine ribose (not shown). The role of positive charges in this region is therefore influenced by the three-dimensional position and orientation of α11-loop–α12 region (Fig. 6), relative to the adenine ribose.

Figure 6. Conformational heterogeneity in the α11-loop-α12 motif.

The NADP+/BvGDH complex (PDB code 1hwz) is used as the reference structure to highlight the position of the cofactor. Complementarity of α9 and α10 in various structures indicates the high degree of convergence. However, the motif α11-loop-α12 is poorly conserved among the various NAD+ and NADP+-dependent enzymes.

The equivalent ‘helix-loop-helix’ motif in the structure of PiGDH has been identified previously as a possible determinant of nucleotide specificity [25]. In this study, a 6-residue deletion in NADP+-dependent vs. NAD+-dependent GDHs was correlated with spatial proximity to an adjacent α-helix (α9 in PiGDH; α12 in EcGDH), thus imparting specificity. However, the sequence alignments in this study were restricted to highly related enzymes from the same phylum (Euryarchaeota). Furthermore, one of the reportedly NADP+-dependent enzymes in their alignment, GDH from Thermotoga maritima, has the 6-residue deletion and nevertheless prefers NAD+ as a cofactor over NADP+ [10]. In principle, our findings are consistent with the work of Bhuiya et al. in identifying a critical role for the nucleotide-proximal ‘helix-loop-helix’ motif. However, the distinguishing feature of our model is that, in NAD+-specific enzymes, the α11-loop-α12 motif is improperly oriented relative to the adenine ribose to contribute positively-charged side chains for 2’-phosphate recognition (Fig. 7). The known structures of NAD+-dependent enzymes (PiGDH, PaGDH, CsGDH) reveal that cofactor recognition is dominated by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds with adenine ribose. The tight hydrophobic contacts from the α11-α12 hairpin to the adenine in the NAD+-only enzymes may also serve to sterically preclude binding to NADP+.

Figure 7. Model for the roles of the P7 residue in cofactor specificity.

Left, cartoon depiction of P7 aspartate in EcGDH, which orients the α11-α12 hairpin toward the 2’-phosphate via a backbone hydrogen bond to Val293 (NH). The critical Ser264 (P8) forms a hydrogen bond with the 2’-phosphate. Right, the P7 aspartate in PiGDH forms hydrogen bonds to 2’-OH and 3’-OH groups of adenine ribose (NAD+). The P8 residue (Ile242) packs against the adenine ring of NAD+.

The P7 glutamate (Glu275) of BvGDH is bifunctional, conferring the dual specificity of the enzyme, as noted above. The composition of PaGDH (P7 glutamate) and the conformation of the α11-α12 hairpin (Fig. 6, blue) resemble BvGDH (Fig. 6, green). However, the proximal lysine (Lys268) is further away from the 2’-phosphate (4.5Å) upon modeling of NADP+ into the active site of PaGDH [19] relative to EcGDH, in which the proximal lysine is significantly closer to the 2’-phosphate. PaGDH also lacks the basic residue in Domain I (equivalent of Lys136 of EcGDH) that may contribute to NADP+ stabilization in the fully closed and catalytically competent conformation. Similarly, the three basic residues of NAD+-specific CsGDH in the α11-α12 hairpin (Fig. 5) are improperly oriented for interactions with the 2’-phosphate.

In summary, cofactor specificity appears to be a function of the arrangement of secondary structural elements, rather than the amino acid sequence per-se. Distinct structural roles for apparently conserved residues, such as an acidic residue (Asp/Glu) at the P7 position suggest caution in interpreting the functional data from mutagenesis and kinetics studies without a structural context, and argue strongly against the tendency to infer coenzyme specificity from primary sequence data alone.

Materials and Methods

Crystallization of EcGDH

EcGDH was expressed and purified as described [26]. Using a 10 mg/ml EcGDH solution in 20mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6), crystals were obtained by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 18°C with 15-25% PEG3350; Tris/Hepes pH 7-8 and 0.2M NaCl as a precipitant solution. Crystals (0.15mm × 0.1mm × 0.1mm) grew to full size over two days. Prior to X-Ray data collection, crystals were cryo-protected in a harvest solution with 25% glycerol, and immediately flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected on the NECAT 24ID-C beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne, USA. Despite numerous strategies to obtain EcGDH in complex with NADP+ and abortive substrate/product complexes, including co-crystallization and soaking experiments, the only crystals obtained were of EcGDH in its free state.

Data collection and refinement

Diffraction data were integrated using HKL2000 [27] and scaled with Scala [28] from the CCP4 program suite [29]. EcGDH crystals belong to the orthorhombic space group P212121 with the biological hexamer as the asymmetric unit. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using CsGDH (PDB code 1bgv; 53% sequence identity) as a search model. Molecular replacement involved division of the polypeptide into the substrate and cofactor domains, and a search for each independent domain against the diffraction data using Phaser [30]. Model building and refinement were performed with COOT [31] and Phenix [32], making use of TLS groups selected on TLSMD server [33]. Non-crystallographic symmetry restraints were used during all cycles of refinement, making use of the new torsion angle NCS algorithm implemented in Phenix. Iterative cycles of model building and refinement were performed using COOT and Phenix respectively until convergence was reached. Structure analysis and model validation were performed with Procheck from CCP4 and Molprobity [29, 34]. Data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession number 4bht.

Table 2.

Crystallization and Data Collection

| Crystallization | |

| protein | 10 mg.mL-1 |

| 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6 | |

| reservoir | 15-25% PEG 3350; |

| 0.1 M Hepes/Tris pH 7-8; | |

| 0.2 M NaCl | |

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | 24ID-C (NECAT, APS) |

| Detector | ADSC Q315 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell lengths (Å) | 101.0, 152.9, 169.4 |

| Asymmetric unit | 6 molecules |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-2.50 (2.59-2.50) |

| Total reflections | 542372 |

| Unique reflections | 91251 |

| Redundancy | 5.9 (4.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 9.7 (49.7) |

| I/σ all data | 18.1 (3.0) |

Values in parentheses correspond to the statistics for the highest resolution shell.

Table 3.

Refinement Statistics

| Model (chain/residues) | |

| A | 6-447 |

| B | 6-447 |

| C | 6-447 |

| D | 6-315, 319-447 |

| E | 6-447 |

| F | 6-447 |

| Ramachandran map (%) | |

| favour./allowed | 98.5 |

| outliers | 1.48 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 15.9/22.7 |

| High res. shell | 20.3/30.7 |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | |

| Protein | 20,371 |

| Glycerol | 18 |

| Hepes | 1 |

| PEG | 1 |

| Water | 773 |

| Average isotropic B-factor (Å2) | 40.6 |

| Average TLS B-factor | 22.5 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.592 |

Superpositions of structures and cofactor/substrate modeling

Crystallization of EcGDH in complex with NADP+ or NADPH was attempted in order to provide insight into determinants of cofactor specificity. However, all experiments (soaking, co-crystallization, ±substrate/product) failed to yield a crystalline complex. As an alternative, superpositions and modeling of the cofactor was performed using the secondary structure matching (SSM) algorithm in PDBSET, as implemented in CCP4 [29]. The bovine glutamate dehydrogenase (BvGDH) structure in complex with NADP+ (1hwz) was used to generate the approximate position of the cofactor in EcGDH. Domain II comprising residues 204-368 of EcGDH was superimposed with the equivalent region of the mammalian enzyme. The final three α-helices of the enzymes and the antenna of BvGDH were excluded from calculations. The root-mean-square (rms) deviations for the alignments were approximately 1Å between bacterial enzymes, and approximately 1.5-1.7Å upon alignment of bacterial/mammalian enzymes. As an example, equivalent regions of Domain II in EcGDH-F superimpose to BvGDH with an rmsd of 1.72Å for 145 aligned Cα atoms and the rms deviation for 185 equivalent Cα atoms of EcGDH-A (6-200) and glutamate-bound CsGDH (PDB code 1bgv; residues 6-203) was 0.95Å. The value increases to 2.3Å when both domains are superimposed simultaneously and such an alignment would ignore the relative domain movements observed in the various subunits and between the different enzymes. Therefore, structural analysis was restricted to pairwise domain superpositions, and no further energy minimizations or rigid-body docking adjustments were performed.

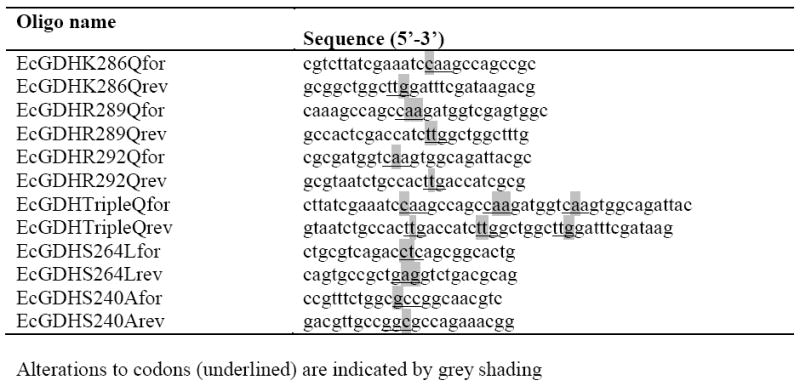

Mutagenesis and kinetic analysis

Site-directed mutagenesis was applied to wild-type EcGDH in pTac-85 [26] using the primers listed in Table 4 (synthesised by Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany) to generate the various mutant constructs. Sequences were verified by automated DNA sequencing (carried out by GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). Expression and purification were as previously described [26], and protein was quantified using the BioRad dye-binding assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with BSA as the standard. EcGDH and mutant variants were diluted when necessary in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, containing 0.25 mg.mL-1 BSA to maintain enzyme stability. Typically, 0.2 μg of purified enzyme in a 10 μL volume was added to a reaction mixture consisting of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, containing l-glutamate and NADP+, bringing the final concentration of glutamate to 0.1 M. For reactions involving the unfavoured coenzyme, up to 6.3 μg of enzyme was used per reaction. Reduction of NAD(P)+ to NAD(P)H was monitored at 340 nm, and reaction rates calculated using an extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM-1.cm-1. The apparent kinetic parameters (Table 1) were determined from initial rate measurements carried out over the NADP+ ranges 3-439, 22-439, 4-429, 6-429, 274-1499, 1867-14938, and 2563-20502 μM, for wild-type, K286Q, R289Q, R292Q, the triple, quadruple and quintuple mutants, respectively. The NAD+ range for the wild-type and triple mutant was 3696-29568 μM, and 4153-33222 and 4062-32493 μM for quadruple and quintuple mutants, respectively. Non-linear regression analysis was carried out using SigmaPlot version 8.02.

Table 4.

Oligonucleotide primers used for mutagenesis

|

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Refined electron density map of EcGDH.

Figure S2: Graphs of activity versus NADP+ concentration for wild-type EcGDH and four mutants.

Figure S3: Graphs of activity versus NAD+ concentration for wild-type and triple glutamine (3Q) mutant EcGDH, and of activity dependence versus both coenzymes for the mutants incorporating serine mutations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland grant number 07/IN.1/B975 to ARK, and Fellowship grant 05/FE1/B857 to PC. We would like to thank the staff of NE-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne, Illinois for their help in collection of X-ray diffraction data. This work is based upon research conducted at the Advanced Photon Source on the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P41RR015301-10) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P41 GM103403-10) from the National Institutes of Health. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Abbreviations

- EcGDH

Escherichia coli glutamate dehydrogenase

- PaGDH

Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus glutamate dehydrogenase

- CsGDH

Clostridium symbiosum glutamate dehydrogenase

- BvGDH

bovine glutamate dehydrogenase

- PiGDH

Pyrobaculum islandicum glutamate dehydrogenase

References

- 1.Britton KL, Baker PJ, Engel PC, Rice DW, Stillman TJ. Evolution of substrate diversity in the superfamily of amino acid dehydrogenases. Prospects for rational chiral synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:938–945. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paradisi F, Collins S, Maguire AR, Engel PC. Phenylalanine dehydrogenase mutants: efficient biocatalysts for synthesis of non-natural phenylalanine derivatives. J Biotechnol. 2007;128:408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada A, Dairi T, Ohno Y, Huang XL, Asano Y. Nucleotide sequencing of phenylalanine dehydrogenase gene from Bacillus badius IAM 11059. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:1994–1995. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura K, Fujii T, Kato Y, Asano Y, Cooper AJ. Quantitation of L-amino acids by substrate recycling between an aminotransferase and a dehydrogenase: application to the determination of L-phenylalanine in human blood. Anal Biochem. 1996;234:19–22. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker PJ, Britton KL, Engel PC, Farrants GW, Lilley KS, Rice DW, Stillman TJ. Subunit assembly and active site location in the structure of glutamate dehydrogenase. Proteins. 1992;12:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stillman TJ, Baker PJ, Britton KL, Rice DW, Rodgers HF. Effect of additives on the crystallization of glutamate dehydrogenase from Clostridium symbiosum. Evidence for a ligand-induced conformational change. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stillman TJ, Migueis AM, Wang XG, Baker PJ, Britton KL, Engel PC, Rice DW. Insights into the mechanism of domain closure and substrate specificity of glutamate dehydrogenase from Clostridium symbiosum. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:875–885. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson PE, Smith TJ. The structure of bovine glutamate dehydrogenase provides insights into the mechanism of allostery. Structure. 1999;7:769–782. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britton KL, Baker PJ, Rice DW, Stillman TJ. Structural relationship between the hexameric and tetrameric family of glutamate dehydrogenases. Eur J of Biochem. 1992;209:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kort R, Liebl W, Labedan B, Forterre P, Eggen RI, de Vos WM. Glutamate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima: molecular characterization and phylogenetic implications. Extremophiles. 1997;1:52–60. doi: 10.1007/s007920050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarrison G, Young DW, Choules GL. Glutamate dehydrogenase from Mycoplasma laidlawii. J Bacteriol. 1972;110:494–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.2.494-503.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker PJ, Britton KL, Rice DW, Rob A, Stillman TJ. Structural consequences of sequence patterns in the fingerprint region of the nucleotide binding fold. Implications for nucleotide specificity. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:662–671. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90848-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wierenga RK, Hol WG. Predicted nucleotide-binding properties of p21 protein and its cancer-associated variant. Nature. 1983;302:842–844. doi: 10.1038/302842a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wierenga R, De Maeyer M, Hol W. Interaction of pyrophosphate moieties with alpha-helices in dinucleotide-binding proteins. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1346–1357. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanukoglu I, Gutfinger T. cDNA sequence of adrenodoxin reductase. Identification of NADP-binding sites in oxidoreductases. Eur J Biochem. 1989;180:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scrutton NS, Berry A, Perham RN. Redesign of the coenzyme specificity of a dehydrogenase by protein engineering. Nature. 1990;343:38–43. doi: 10.1038/343038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilley KS, Baker PJ, Britton KL, Stillman TJ, Brown PE, Moir AJ, Engel PC, Rice DW, Bell JE, Bell E. The partial amino acid sequence of the NAD(+)-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase of Clostridium symbiosum: implications for the evolution and structural basis of coenzyme specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1080:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90001-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capone M, Scanlon D, Griffin J, Engel PC. Re-engineering the discrimination between the oxidised coenzymes NAD+ and NADP+ in a glutamate dehydrogenase and a reappraisal of the specificity of the wild-type enzyme. FEBS J. 2011;278:2460–2468. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira T, Panjikar S, Carrigan JB, Hamza M, Sharkey MA, Engel PC, Khan AR. Crystal structure of NAD+-dependent Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus glutamate dehydrogenase reveals determinants of cofactor specificity. J Struct Biol. 2012;177:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korber FCF, Rizkallah PJ, Attwood TK, Wootton JC, McPherson MJ, North ACT, Geddes AJ, Abeysinghe SB, Baker PJ, Dean JLE, et al. Crystallization of the NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1270–1273. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Totir M, Echols N, Nanao M, Gee CL, Moskaleva A, Gradia S, Iavarone AT, Berger JM, May AP, Zubieta C, et al. Macro-to-micro structural proteomics: native source proteins for high-throughput crystallization. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharkey MA, Engel PC. Modular coenzyme specificity: a domain-swopped chimera of glutamate dehydrogenase. Proteins. 2009;77:268–278. doi: 10.1002/prot.22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stillman TJ, Baker PJ, Britton KL, Rice DW. Conformational flexibility in glutamate dehydrogenase. Role of water in substrate recognition and catalysis. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1131–1139. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TJ, Peterson PE, Schmidt T, Fang J, Stanley CA. Structures of bovine glutamate dehydrogenase complexes elucidate the mechanism of purine regulation. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:707–720. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhuiya MW, Sakuraba H, Ohshima T, Imagawa T, Katunuma N, Tsuge H. The first crystal structure of hyperthermostable NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase from Pyrobaculum islandicum. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharkey MA, Engel PC. Apparent negative co-operativity and substrate inhibition in overexpressed glutamate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabsch W. Automatic indexing of rotation diffraction patterns. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1988;21:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Refined electron density map of EcGDH.

Figure S2: Graphs of activity versus NADP+ concentration for wild-type EcGDH and four mutants.

Figure S3: Graphs of activity versus NAD+ concentration for wild-type and triple glutamine (3Q) mutant EcGDH, and of activity dependence versus both coenzymes for the mutants incorporating serine mutations.