Abstract

Background

The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia have developed "guidance" for the supply of several medicines available without prescription to the general public. Limited research has been published assessing the effect of these guidelines on the provision of medication within the practice of pharmacy.

Objective

To assess appropriate supply of non-prescription antifungal medications for the treatment of vaginal thrush in community pharmacies, with and without a guideline. A secondary aim was to describe the assessment and counseling provided to patients when requesting this medication.

Methods

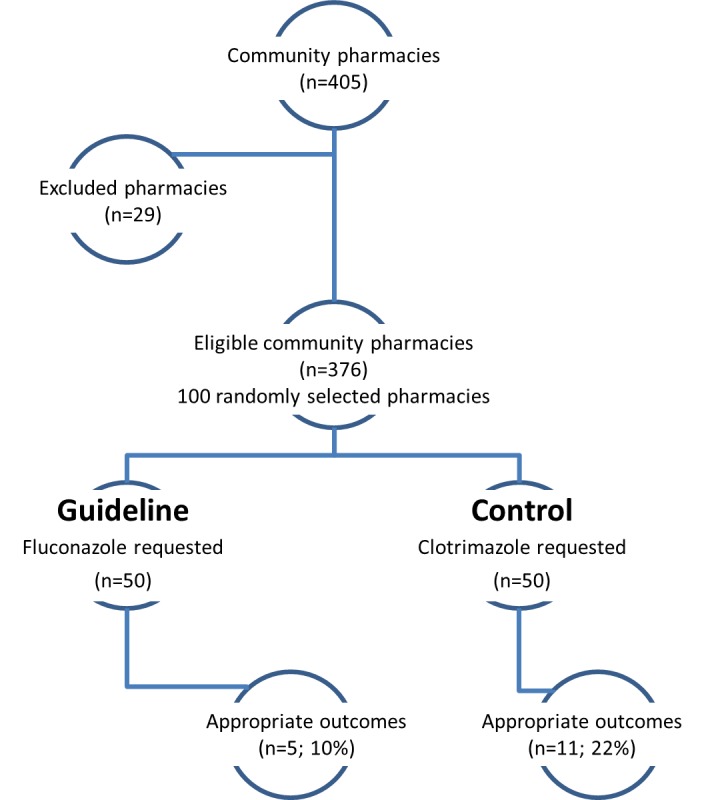

A randomized controlled trial was undertaken whereby two simulated patients conducted visits to 100 randomly selected community pharmacies in a metropolitan region. A product-based request for fluconazole (an oral antifungal that has a guideline was compared to a product-based request for clotrimazole (a topical antifungal without a guideline). The same patient details were used for both requests. Outcome measures of the visits were the appropriateness of supply and referral to a medical practitioner.

Results

Overall 16% (n=16) of visits resulted in an appropriate outcome; 10% (n=5) of fluconozaole requests compared with 22% (n=11) of clotrimazole requests (chi-square=2.68, p=0.10). There was a difference in the type of assessment performed by pharmacy staff between visits for fluconazole and clotrimazole. A request for clotrimazole resulted in a significant increase in frequency in regards to assessment of the reason for the request (chi-square=8.57, p=0.003), symptom location (chi-square=8.27, p=0.004), and prior history (chi-square=5.09, p=0.02).

Conclusions

Overall practice was poor, with the majority of pharmacies inappropriately supplying antifungal medication. New strategies are required to improve current practice of community pharmacies for provision of non-prescription antifungals in the treatment of vaginal thrush.

Keywords: Patient Simulation; Candidiasis, Vulvovaginal; Community Pharmacy Services; Professional Practice; Pharmacies; Australia

Introduction

The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) has provided practice guidance for the provision of non-prescription medication via community pharmacies.1 The practice guidance consists of an overall PSA Standard for the supply of non-prescription medication to consumers, along with specific guidelines developed for the supply of Pharmacist Only Medications.2,3,4,5,6 Non-prescription medication supply is also referred to as dispensing in some countries. Appraisal of the impact of the PSA guidelines on pharmacy practice has not been published in the scientific literature.

The treatment of vaginal thrush in the community pharmacy setting is ideal to test the impact of a PSA guideline on the practice of community pharmacy staff. Approximately 75% of women suffer from vaginal thrush at sometime during their lives, making it one of the most common ailments presented in the community pharmacy. Symptoms are often non-discriminatory which can lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. Fluconazole and clotrimazole, are medications that are both indicated for vaginal thrush, available without prescription. In 2004, when fluconazole first became available without prescription, the PSA developed a guideline to aid pharmacists in the provision of fluconazole for this condition.4 It should be noted that non-pharmacist members of staff may not be familiar with the guideline, however under Australian law, a pharmacist must be involved with the sale of fluconazole. By contrast, clotrimazole has been available without prescription longer than fluconzole and has yet to have a guideline developed for supply.

Internationally, Watson and colleagues in the UK compared three dissemination strategies of evidenced-based guidelines for treatment of vaginal thrush in community pharmacies.7,8,9 The authors examined practice pre and post dissemination over a period of seven months and found no improvement in outcome regardless of dissemination strategy (defined as appropriate supply or non-supply). At the same time, Watson found, that pharmacist knowledge was high post guideline dissemination.8 Watson’s work suggests that knowledge does not correlate to compliant behavior, which may be attributed to psychological effects such as existing attitudes and intentions.9

The aim of this study was to compare the practice of community pharmacies in response to requests for antifungal medication with and without a PSA guideline. The primary objective was to compare the incidence of appropriate patient outcome (in this case non-supply of the requested medication and referral to a medical practitioner) between groups. A secondary aim was to describe the assessment and counseling provided to patients when requesting this medication.

Methods

Ethics

The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee granted approval for the study.

Setting

The study was a single-blind randomized controlled trial. The study was conducted in a metropolitan region of Australia. Community pharmacies (n=405) in the metropolitan area were eligible for inclusion during 2008. Pharmacies that employed staff known to the simulated patients, had previous knowledge of the study, or did not supply non-prescription medication to the public were excluded (n=29). From the remaining 376 eligible pharmacies, 100 community pharmacies in a metropolitan area were randomly allocated to one of two groups: a request for the product with a guideline (fluconazole), or a request for a product without a guideline (clotrimazole). The sample size chosen provided an 85% chance of detecting a 30% difference at a 5% significance level (two tailed). Randomisation was performed by use of a random number generator.

Scenario

Visits were performed using the same simulated patient methodology as our previous study.10 Briefly, one of either two female simulated patients in their mid-20’s presented to pharmacies in the guideline and non-guideline groups with a request for either Diflucan® (fluconazole) or Canesten® (clotrimazole) respectively (Table 1). Request by brand name was chosen in consultation with practicing community pharmacists as this was likely to be representative of actual practice in Australia due to the widespread advertising of antifungals for the treatment of vaginal thrush. Upon entering a pharmacy, the request was made to any member of staff, based on availability. The simulated patients were to provide only information specifically pertaining to questions asked. Training of the simulated patients was conducted via role-play and by practicing the scenario in eight pharmacies that were not part of the study. Completion of a written data collection form by the simulated patients occurred immediately post-visit.

Table 1.

Scenario description

Variables including the age and position held by pharmacy staff members were assessed by simulated patient observation and thus may potentially be subject to estimation error. To minimize potential error, age was grouped by decade and an ‘unsure’ category was used for visits where the staff position was difficult to determine. In addition, the results were recorded immediately post-visit and relied on recollection by the simulated patient. Employment position was defined as the person who completed the consultation that resulted in advice, referral or sale (or all three). Other variables measured included:

Outcome

The appropriate outcome was referral to a medical practitioner with non-supply of antifungal medication. Medications were only purchased when advised to do so. For the scenario presented, the symptoms provided were atypical of vaginal thrush. In addition, the PSA guideline recommends patients with first-time thrush to have the diagnosis confirmed by a medical practitioner. Data was also collected on the amount and type of assessment and counselling provided to the simulated patient. Assessment and counselling incidence was reported if any assessment or counselling took place. The amount of assessment was defined as the number of questions asked. The amount of counselling was defined as the number of counselling elements verbally provided to the patient during the consultation.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all data. Comparison between data was via Pearson’s chi-square and Student t-test for categorical and continuous data respectively. Significance was set at the 5% level. For the primary objective, the incidence of referral advice and medication non-supply were the dependant variables compared between groups.

Results

Demographic data of the 100 community pharmacies visited is presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences found for pharmacy or counselor characteristics. The average time taken for the visit also did not differ between groups. The appropriate outcome for the scenario was determined as non-supply of antifungal medication and referral to a medical practitioner for assessment of the patient’s symptoms. Overall, 16% (n=16) of visits resulted in an appropriate outcome (Figure 1). An appropriate outcome was achieved in 10% (n=5) of the guideline cohort and 22% (n=11) of the control cohort (Table 3). The incidence of an appropriate outcome in the guideline cohort was half that of the control, however the result did not achieve statistical significance (chi-square=2.68, df=1, p=0.10). Pharmacy staff provided referral advice when selling antifungal medication in 32% (n=16) of the guideline group and 40% (n=20) of the non-guideline group. Antifungal medication sold without any referral advice occurred in 58% (n=29) of visits in the guideline group, which was significantly more likely when compared with 38% (n=19) of visits in the control group (chi-square=4.01, df=1, p<0.05). In six of the 100 visits, pharmacy staff recommended treatment with an antifungal, despite indicating to the patient that they either were unlikely to have thrush (n=5) or that they should see a medical practitioner due to lack of a prior history of thrush (n=1). Comparison between groups was not performed for this result.

Table 2.

Pharmacy and pharmacy staff characteristics

| Guideline (n) n=50 |

Control (n) n=50 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacy Type | n.s. | ||

| Independent | 50 (25) | 60 (30) | |

| Chain | 50 (25) | 40 (20) | |

| Pharmacy Location | n.s. | ||

| Shopping Centre | 54 (27) | 54 (27) | |

| Street | 22 (11) | 30 (15) | |

| Medical Centre | 22 (11) | 16 (8) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Pharmacy Busyness | n.s. | ||

| Staff > Customer | 76 (38) | 76 (38) | |

| Staff ≤ Customers | 24 (12) | 24 (12) | |

| Staff Gender | n.s. | ||

| Female | 76 (38) | 82 (41) | |

| Male | 24 (12) | 18 (9) | |

| Employment Position | n.s. | ||

| Pharmacist Assistant | 36 (18) | 34 (17) | |

| Pharmacist | 28 (14) | 32 (16) | |

| Pharmacist consulted (by assistant) | 6 (3) | 8 (4) | |

| Pharmacist referral (by assistant) | 20 (10) | 14 (7) | |

| Other/Unsure | 10 (5) | 12 (6) | |

| Estimated Staff Age (years) | n.s. | ||

| < 20 | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| 20 – 29 | 50 (25) | 54 (27) | |

| 30 – 39 | 18 (9) | 8 (4) | |

| 40 – 49 | 14 (7) | 20 (10) | |

| > 50 | 10 (5) | 18 (9) | |

| Visit Time (minutes) | 1.3 ± 1a | 1.5 ± 1.1a | n.s. |

| a mean ± standard deviation | |||

Table 3.

Outcome measures

| Guideline (n) n=50 |

Control (n) n=50 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Referral without supply | 10% (5) | 22% (11) | n.s. |

| Referral with supply | 32% (16) | 40% (20) | n.s. |

| Supply without referral | 58% (29) | 38% (19) | p<0.05 |

| Incidence of assessment | 84% (42) | 94% (47) | n.s. |

| Amount of assessment | 3.3 ± 2.7 a | 4.2 ± 3.1 a | n.s. |

| Incidence of counseling | 84% (42) | 90% (45) | n.s. |

| Amount of counseling | 2.8 ± 2 a | 3.2 ± 2.4 a | n.s. |

| a mean ± standard deviation | |||

Figure 1.

Consort diagram (differences in outcome p>0.05)

The incidence and amount of both assessment and counselling is presented in Table 3 and were not significantly different between groups. The most frequently asked questions are listed in Table 4. A significantly increased incidence was noted in the non-guideline group for assessment of prior history of thrush (chi-square=5.09, df=1, p=0.02), the reason for the medication request (chi-square=8.57, df=1, p=0.003), and a question regarding the location of the patient’s symptoms (chi-square=8.27, df=1, p=0.004).

Table 4.

| Guideline (n) n=50 |

Control (n) n=50 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Who is the medication for? | 30% (15) | 32% (16) | n.s. |

| Medication history? | 44% (22) | 28% (14) | n.s. |

| Have you had thrush before? | 28% (14) | 50% (25) | p=0.02 |

| Have you used the medication before? | 60% (30) | 48% (24) | n.s. |

| Why do you need the medication? | 14% (7) | 40% (20) | p=0.003 |

| What are your symptoms? | 14% (7) | 30% (15) | n.s. |

| Are you pregnant/breastfeeding? | 22% (11) | 10% (5) | n.s. |

| Have you taken antibiotics recently? | 16% (8) | 26% (13) | n.s. |

| Is it internal? | 2% (1) | 20% (10) | p=0.004 |

Discussion

A minority of pharmacy staff provided appropriate advice in both the guideline and the control groups. The minority of pharmacy visits resulting in an appropriate outcome is consistent with prior studies examining the provision of other non-prescription medication in the same population.10,11 The result is also consistent with international research assessing the provision of anti-fungal medication for vaginal thrush without prescription.8,12

From our results it is clear that the PSA guideline for supply of fluconazole for vaginal thrush is not performing its intended purpose of ensuring that supply is appropriate. This guideline was disseminated four years prior to the current study. When compared with Watson and colleagues' findings that appropriate pharmacy practice did not improve post-guideline implementation8, the results suggest that additional time post-dissemination does not result in practice improvement. Non-pharmacist members of staff may not be familiar with the guideline, however under Western Australian law, a pharmacist must be involved with the sale. In over one third of cases, this law was not followed in the current study.

Approximately half of the pharmacy staff that inappropriately provided antifungal medication also provided referral advice to "see a medical practitioner if symptoms persist". Visits in the guideline group were significantly more likely to result in antifungal medication supply without referral advice. When supplying medication that is inappropriate, lack of advice to the patient regarding what to do if symptoms persist may further delay appropriate patient care. Misdiagnosis may also involve vaginal thrush occurring alongside other vaginal infections such as bacterial vaginosis and Chlamydia trachomatis which require treatment with antibiotics and thus a consultation with a medical practitioner. In these cases, if women achieved symptomatic relief for their vaginal thrush, they may be less likely to seek medical treatment and continue to be affected by the other infection. Pharmacy staff in a small proportion of visits gathered adequate information to make an appropriate decision, accurately identified an appropriate reason for non-supply, yet proceeded to recommend use of an antifungal. These results suggest that decision-making is a discrete step in handling medication requests after information gathering and processing.

While the rate and amount of both assessment and counseling between groups was not different, there was a significant difference in the type of assessment conducted. Literature has previously identified that different types of requests for non-prescription medication are associated with variation in the assessment pharmacy staff provide: direct-product versus symptom-based requests13,14,15, and requests for medication for differing medical conditions.16,17,18,19 In this study, a request for clotrimazole was significantly more likely to elicit assessment of the patient’s reason for the request and prior history than a request for fluconazole. This was despite both medications being indicated for the same condition and the same patient details being provided. As the disease state and the patient are controlled, our research suggests that variables related to the medication itself contribute to a difference in assessment. These variables may include pharmacy staff product knowledge, the fact that clotrimazole has been available over the counter for longer, that clotrimazole is indicated for more than one condition and is available in multiple preparations via more than one route of administration or indeed whether the medication has a guideline for supply.

Conclusions

In the majority of visits, pharmacy staff inappropriately supplied antifungal medication to the simulated patient, with symptoms inconsistent with vaginal thrush and without a prior history of the condition. The presence of an existing guideline for the supply of fluconazole did not increase the incidence of an appropriate outcome.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Carl R. Schneider, Faculty of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney. Sydney (Australia). carl.schneider@sydney.edu.au

Lyndal Emery, School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia. Crawley (Australia)..

Raisa Brostek, School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia. Crawley (Australia)..

Rhonda M. Clifford, School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia. Crawley (Australia).

References

- 1.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Standards for the provision of Pharmacy Medicines and Pharmacist Only Medicines in community pharmacy. Canberra: PSA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Supply of levonorgestrel as a Pharmacist Only Medicine for emergency contraception (EC) Canberra: PSA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Provision of orlistat as a Pharmacist Only Medicine. Canberra: PSA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Provision of oral fluconazole as a Pharmacist Only Medicine for the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Canberra: PSA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Provision of pantoprazole as a Pharmacist only medicine. Canberra: PSA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Provision of chloramphenicol for ophthalmic use as a Pharmacist Only medicine. Canberra: PSA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson MC, Bond CM, Grimshaw JM, Mollison J, Ludbrook A, Walker AE. Educational strategies to promote evidence-based community pharmacy practice: a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) Fam Pract. 2002;19:529–536. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson MC, Bond CM, Grampian Evidence Based Community Pharmacy Guidelines Group Evidence-based guidelines for non-prescription treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:129–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1024819515862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson MC, Bond CM, Walker A, Grimshaw J. Why educational interventions are not always effective: a theory-based process evaluation of a randomised controlled trial to improve non-prescription medicine supply from community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider CR, Everett AW, Geelhoed E, Kendall PA, Clifford RM. Measuring the assessment and counselling provided with the supply of non-prescription asthma reliever medication: a simulated patient study. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1512–1518. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider CR, Everett AW, Geelhoed E, Kendall PA, Murray K, Garnett P, Salama M, Clifford RM. Provision of primary care to patients with cough in the community pharmacy setting. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:402–408. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris P. Purchasing restricted medicines in New Zealand pharmacies: results from a "mystery shopper" study. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24:149–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1019506120713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benrimoj SI, Werner JB, Raffaele C, Roberts AS. A system for monitoring quality standards in the provision of non-prescription medicines from Australian community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bissell P, Ward PR, Noyce PR. Variation within community pharmacy. Part 1. Responding to requests for over-the-counter medicines. J Soc Admin Pharm. 1997;14:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson MC, Hart J, Johnston M, Bond CM. Exploring the supply of non-prescription medicines from community pharmacies in Scotland. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:526–535. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John DN, Krska J, Hansford D. Are customers requesting medicines by name less likely to be advised or referred? Provision of over-the-counter H2-receptor antagonists and alginate products from pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003;11:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly FS, Williams KA, Benrimoj SI. Does Advice from Pharmacy Staff Vary According to the Nonprescription Medicine Requested? Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1877–1886. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emmerton L, Shaw J. The influence of pharmacy staff on non-prescription medicine sales. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bissell P, Ward PR, Noyce PR. Variation within community pharmacy. Part 2. Responding to the presentation of symptoms. J Soc Admin Pharm. 1997;14:105–115. [Google Scholar]