Abstract

Research has documented significant relationships between sexual and gender minority stress and higher rates of suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation and attempts) and substance use problems. We examined the potential mediating role of substance use problems on the relationship between sexual and gender minority stress (i.e., victimization based on lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender identity; LGBT) and suicidality. A non-probability sample of LGBT patients from a community health center (N = 1457) ranged in age 19 to 70 years. Participants reported history of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts, and substance use problems, as well as experiences of LGBT-based verbal and physical attacks. Substance use problems were a significant partial mediator between LGBT-based victimization and suicidal ideation and between LGBT-based victimization and suicide attempts for sexual and gender minorities. Nuanced gender differences revealed that substance use problems did not significantly mediate the relationship between victimization and suicide attempts for sexual minority men. Substance use problems may be one insidious pathway that partially mediates the risk effects of sexual and gender minority stress on suicidality. Substances might be a temporary and deleterious coping resource in response to LGBT-based victimization, which have serious effects on suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Keywords: LGBT, victimization, suicide, substance use problems, sexual and gender minority stress

Sexual minorities (i.e., individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual) and gender minorities (i.e., individuals who identify as transgender) are at greater risk for suicidality than heterosexuals (Cochran & Mays, 2000, 2009; Haas et al., 2011). For instance, a recent meta-analysis found that gay and bisexual men are four times as likely to attempt suicide over their lifetimes as heterosexual men, and lesbian and bisexual women are twice as likely as their heterosexual counterparts to do so (King et al., 2008). Furthermore, sexual minorities are twice as likely to report suicidal ideation as heterosexual individuals (King et al., 2008). Gender minorities are also at a high risk for suicidality. Although these disparities exist, there is limited research addressing suicidality within sexual and gender minority communities (Haas et al., 2011); thus, the present study aimed to better understand factors that put sexual and gender minorities (i.e., LGBT individuals) at greater risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) provides a conceptual framework to understand LGBT health disparities. According to this model, sexual minorities experience unique and chronic stressors (e.g., victimization, internalized homophobia) that are specific to their identities, which in turn have deleterious effects on their mental health (Meyer, 2003). Experiences of sexual minority stress stigmatize sexual minorities and can lead to isolation and suicidality. Some aspects of this model can be extended to gender minorities due to their unique experiences with gender minority stressors. In fact, experiencing discrimination and oppression is related to suicidality for LGBT individuals (Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz, 2006; Diaz, Ayala et al., 2001; Savin-Williams, 1994). However, research has not adequately examined mediating factors that explain these relations (Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Due to heterosexism and barriers to seeking support and sensitive health services (Dean et al., 2000), experiences of minority stress may influence some LGBT individuals to use substances as a way to cope with negative minority stressors. Substance use and abuse can be conceptualized as methods to regulate or avoid negative affect and to reduce tension (Cabaj, 2000; Cooper et al., 1995; Greeley & Oei, 1999; Hughes, Matthews, Razzano, & Aranda, 2002). Experiences of discrimination are related to negative affect (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 1999; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 1995); thus, LGBT individuals may misuse substances as a means of coping with discrimination and regulating negative feelings as a result of minority stressors (McKirnan & Peterson, 1988). In fact, sexual minority stress is related to increased substance misuse (Amadio, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008; McCabe et al., 2010).

Purpose of Study

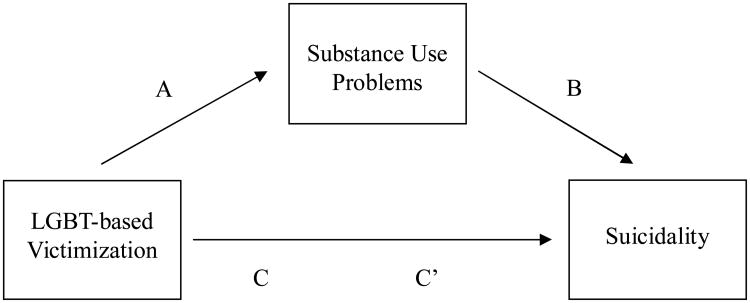

LGBT-specific stress and substance misuse are both related to greater risk for suicidality (e.g., Clements-Nolle et al., 2006); additionally, minority stress is related to increased risk for substance misuse (e.g., McCabe et al., 2010). Given that the relationships among these variables have not been adequately examined, the present study was designed to examine substance use problems as a mediator between LGBT-based victimization and suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) in a cross-sectional sample of LGBT individuals. Consistent with the basic assumptions of mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986), we hypothesized that LGBT-based victimization will be related to higher odds of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (path C in Figure 1) and higher odds of substance use problems (path A). Additionally, while accounting for LGBT-based victimization, we hypothesized that substance use problems will be related to higher odds of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (path B). Thus, substance use problems were hypothesized to mediate the relationship between LGBT-based victimization and suicidal ideation and between LGBT-based victimization and suicide attempts (path C′) for LGBT individuals. As such, the purpose of this paper is to illuminate some potential cross-sectional relationships that might have been often overlooked in the extant literature as well as to inform future longitudinal research and clinical interventions. Furthermore, since the literature has documented some gender differences in sexual minority risk for suicidality and substance misuse (King et al., 2008), we examined these relationships independently for sexual minority women and men as well as the aggregate sample of LGBTs

Figure 1.

Mediation model.

Method

Secondary data analyses were conducted on a survey of patients of an urban community health center serving the general community and with a specific focus on LGBTs in a New England city. From 2001 to 2003, patients were invited to complete the survey while they waited for their medical or mental health appointments. Participants took about two to six minutes to complete a 25-item questionnaire, which asked questions about demographics, clinical history, and experience at the health center. In the demographics section, participants were asked to identify their sexual orientation with the following response options: Homosexual (Gay/Lesbian), Heterosexual (Straight), Bisexual, Not sure/Undecided, and Prefer not to say. They were also asked to identify their gender identity with the following response options: Male, Female, or Transgender. A total of 3103 patients participated in the survey, including LGBTs and heterosexuals. For the purposes of this paper, only participants who identified as LGBT were included in the analysis (N = 1579).

Data were cleaned for missing values and 122 participants were removed for having missing data on the study's measures. The final sample size was comprised of 1457 LGBT participants. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 70 (M = 36.61, SD = 9.41), and were predominately male (77.6%), White (85%), and lesbian or gay (89.9%) identified. The sample had a total of 305 sexual minority women, 1130 sexual minority men, and 16 transgender participants who also identified as sexual minorities. Six participants had missing data for gender; however, they were still included in the aggregate sample analyses because they identified as a sexual minority. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics.

| Suicidal Ideation | Suicide Attempts | Total Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| n = 1048 | n = 409 | n = 1274 | n = 183 | N = 1457 | |

| Gender | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Female | 71.1 (217) | 28.9 (88) | 84.9 (259) | 15.1 (46) | 20.9 (305) |

| Male | 72.7 (821) | 27.3 (309) | 88.4 (999) | 11.6 (131) | 77.6 (1130) |

| Transgender/Other/Intersexed | 31.3 (5) | 68.8 (11) | 68.8 (11) | 31.3 (5) | 1.1 (16) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 77.8 (28) | 22.2 (8) | 88.9 (32) | 11.1 (4) | 2.5 (36) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 68.9 (51) | 31.3 (23) | 83.8 (62) | 16.2 (12) | 5.1 (74) |

| Hispanic/Latina(o) | 87.8 (65) | 12.2 (9) | 94.6 (70) | 5.4 (4) | 5.1 (74) |

| Native American | 42.9 (3) | 57.1 (4) | 85.7 (6) | 14.3 (1) | 0.5 (7) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 71.1 (880) | 28.9 (358) | 87.2 (1080) | 12.8 (158) | 85 (1238) |

| Multi-racial | 66.7 (4) | 33.3 (2) | 66.7 (4) | 33.3 (2) | 0.4 (6) |

| Other | 70.6 (12) | 29.4 (5) | 88.2 (15) | 11.8 (2) | 1.2 (17) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||||

| Lesbian/Gay | 73 (956) | 27 (354) | 88.3 (1157) | 11.7 (153) | 89.9 (1310) |

| Bisexual | 62.6 (92) | 37.4 (55) | 79.6 (117) | 20.4 (30) | 10.01 (147) |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 62.8 (86) | 37.2 (51) | 78.8 (108) | 21.2 (29) | 9.4 (137) |

| Some college or higher | 72.8 (960) | 27.2 (358) | 88.3 (1164) | 11.7 (154) | 90.5 (1318) |

| Individual/Family Income | |||||

| < $34,999 | 66 (371) | 34 (191) | 81.9 (460) | 18.1 (102) | 38.6 (562) |

| > $35,000 | 75.5 (645) | 24.5 (209) | 91.2 (779) | 8.8 (75) | 58.6 (854) |

| HIV Status | |||||

| HIV-negative | 74 (736) | 26 (259) | 88 (876) | 12 (119) | 68.3 (995) |

| HIV-positive | 64.4 (163) | 35.6 (90) | 84.2 (213) | 15.8 (40) | 17.4 (253) |

| Unknown | 70.4 (140) | 29.6 (59) | 87.9 (175) | 12.1 (24) | 13.7 (199) |

| Substance Use Problem | |||||

| No | 79.7 (907) | 20.3 (231) | 92.3 (1050) | 7.7 (88) | 78.1 (1138) |

| Yes | 44.2 (141) | 58.8 (178) | 70.2 (224) | 29.8 (95) | 21.9 (319) |

| LGBT-Based Victimization | |||||

| Physical Attacks | |||||

| No | 75.1 (910) | 24.9 (301) | 90.1 (1091) | 9.9 (120) | 83.1 (1211) |

| Yes | 56.1 (138) | 43.9 (108) | 74.4 (183) | 25.6 (63) | 16.9 (246) |

| Verbal Attacks | |||||

| No | 83.4 (512) | 16.6 (102) | 93 (571) | 7 (43) | 42.1 (614) |

| Yes | 63.6 (536) | 36.4 (307) | 83.4 (703) | 16.6 (140) | 57.9 (843) |

Note. LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

Measures

Participants reported basic demographic information, such as gender (i.e., male, female, or transgender), racial/ethnic background, sexual orientation, educational level, family income, and HIV status (i.e., HIV-negative, HIV-positive, Unknown, or Prefer not to say) prior to completing questions related to their mental health and victimization. Lifetime suicidal ideation was measured with the following item: “In your lifetime, have you ever thought seriously about killing yourself?” History of lifetime suicide attempts was measured with the following item: “In your lifetime, have you ever made a suicide attempt?” A self-reported lifetime problem with substances was measured with the following item: “In your lifetime have you ever felt you had a problem with substance use?” An LGBT-based victimization two-item index score was measured by summing responses of participants who reported being physically or verbally attacked when answering the following question: “Have any of the following happened to you because you are lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender?” Participants responded as No or Yes to all of the measures, which were coded as 0 or 1, respectively.

Data Analysis

Descriptive and regression analyses were conducted using PASW18.0 Statistical Software (SPSS Inc., 2009). Nine bivariate logistic regression analyses were used to examine the relationships among the variables and to test for mediation. The first three regressions were conducted to test for mediation and its assumptions for the suicidal ideation outcome variable; three additional regressions were conducted for the suicide attempts outcome variable. For each suicidality outcome variable and in alignment with mediation testing procedures (Baron & Kenny, 1986), the first regression examined the odds of sucidality related to LGBT-based victimization; the second regression examined the odds of substance use problems related to LGBT-based victimization; and the third regression model examined the odds of suicidality related to substance use problems while accounting for LGBT-based victimization. Since the mediator and outcome variables in the model are dichotomous, standardization procedures were conducted to correct for scaling issues as recommended by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Standardized coefficients were used for the Sobel test, which enabled a more formal and precise test of mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2002). The unstandardized unadjusted (UOR), adjusted odds (AOR) ratios, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Bivariate regression results testing the mediating effects of substance use problems on the relationship between victimization and suicidal ideation.

| Suicidal Ideation Mediation Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Aggregate Sample of Sexual and Gender Minorities | Sexual Minority Women | Sexual Minority Men | ||||

| Unadj. OR (S.E.) | AOR (95% CI) | Unadj. OR (S.E.) | AOR (95% CI) | Unadj. OR | AOR (95% CI) | |

| 1: Outcome: Suicidal Ideation | ||||||

| Victimization | .74*** (.09) | 2.11*** (1.78, 2.49) | .67** (.20) | 1.96** (1.34, 2.88) | .79*** (.10) | 2.20*** (1.82, 2.66) |

| 2. Outcome: Substance Use Problems | ||||||

| Victimization | 1.41 *** (.14) | 2.35*** (1.96, 2.81) | .68** (.22) | 1.98** (1.30, 3.03) | .89*** (.10) | 2.44*** (1.99, 2.99) |

| 3: Outcome: Suicidal Ideation | ||||||

| Victimization | .57*** (.09) | 1.76*** (1.48, 2.1) | .56** (.20) | 1.75** (1.18, 2.61) | .60*** (.10) | 1.82*** (1.49, 2.22) |

| Substance Use | 1.41***(.14) | 4.10*** (3.12, 5.38) | 1.18*** (.31) | 3.25*** (1.79, 5.91) | 1.45 *** (.16) | 4.24*** (3.11, 5.79) |

Note. Unadj. OR = unadjusted odds ratio; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; S.E. = Standard Error; CI = 95% confidence interval, which is noted in parentheses.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Bivariate regression results testing the mediating effects of substance use problems on the relationship between victimization and suicide attempts.

| Suicide Attempts Mediation Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Aggregate Sample of Sexual and Gender Minorities | Sexual Minority Women | Sexual Minority Men | ||||

| Unadj. OR (S.E.) | AOR (95% CI) | Unadj. OR (S.E.) | AOR (95% CI) | Unadj. OR | AOR (95% CI) | |

| 1: Outcome: Suicide Attempts | ||||||

| Victimization | .81*** (.11) | 2.24*** (1.8, 2.79) | .80** (.24) | 2.22** (1.38, 3.55) | .87*** (.13) | 2.39*** (1.84, 3.09) |

| 2. Outcome: Substance Use Problems | ||||||

| Victimization | .85*** (.09) | 2.35*** (1.96, 2.81) | .68** (.22) | 1.98** (1.30, 3.03) | .89*** (.10) | 2.44*** (1.99, 2.99) |

| 3: Outcome Suicide Attempts | ||||||

| Victimization | .59*** (.12) | 1.80*** (1.43, 2.27) | .62* (.25) | 1.87* (1.13, 3.07) | .65*** (.14) | 1.91*** (1.46, 2.51) |

| Substance Use | 1.40*** (.17) | 4.07*** (2.91, 5.69) | 1.62*** (.35) | 5.03*** (2.53, 10.01) | 1.35 *** (.20) | 3.84*** (2.59, 5.70) |

Note. Unadj. OR = unadjusted odds ratio; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; S.E. = Standard Error; CI = 95% confidence interval, which is noted in parentheses.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Results

Basic Group Comparisons

Basic demographic descriptive data are presented in Table 1. Preliminary group comparisons between the demographic characteristics and the suicidality outcome variables indicated some differences. Results from univariate analyses indicated that bisexual participants were more likely than lesbians and gay men to have suicidal ideation (χ2 = 7.07, df = 1, p < .05) and suicidal attempts (χ2 = 9.17, df = 1, p < .01). Additionally, participants with a high school degree or less were more likely than participants with some college education or higher to have suicidal ideation (χ2 = 6.22, df = 1, p < .05) and suicidal attempts (χ2 = 10.15 df = 1, p < .01). Similarly, participants with a family income less than $34,999 were more likely than participants with an income greater than $35,000 to have suicidal ideation (χ2 = 15.13, df = 1, p < .001) and suicidal attempts (χ2 = 27, 19, df = 1, p < .001). Moreover, participants who were HIV-positive were more likely than participants who were HIV-negative to have suicidal ideation (χ2 = 9.12, df = 1, p < .01) but they did not differ on suicidal attempts (χ2 = 2.69, df = 1, p = .11). Participants who were HIV-negative and participants who did not know their HIV status did not significantly differ on suicidal ideation (χ2 = 1.11, df = 1, p = .29) or suicidal attempts (χ2 = .002, df = 1, p = .97). Men and women also did not significantly differ on suicidal ideation (χ2 = .27, df = 1, p = .6) or suicidal attempts (χ2 = 2.7, df = 1, p = .1). Similarly, racial minority participants did not significantly differ from White participants on suicidal ideation (χ2 = 2.33, df = 1, p = .13) or suicidal attempts (χ2 = .19, df = 1, p = .66).

Mediation Analyses

Results for the regression analyses testing the mediation models are reported in Tables 2 and 3. It is important to note that we did not conduct separate regression analyses for participants who identified as transgender due to the small sample size (n = 16); However, they were only included in the aggregate sample.

Aggregate sample

As an aggregate sample of LGBT participants, LGBT individuals who reported experiencing LGBT-based victimization (i.e., verbal and physical attacks) reported higher odds of a lifetime substance use problem (AOR = 2.35), suicidal ideation (AOR = 2.11), and suicide attempts (AOR = 2.24) than LGBT individuals who did not report any history of victimization. When accounting for LGBT-based victimization, LGBTs who reported lifetime substance use problems reported higher odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 4.1) and suicide attempts (AOR = 4.07). The odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 1.76) and suicidal attempts (AOR = 1.8) related to LGBT-based victimization decreased when accounting for the mediating relations of substance use problems. Sobel tests indicated that substance use problems partially mediated the relationship between LGBT-based victimization and suicidal ideation (t = 6.07, SE = 0.01, p < .001) and between LGBT-based victimization and suicide attempts (t = 6.84, SE = 0.02, p < .001).

Sexual minority women

Sexual minority women who reported experiencing LGBT-based victimization reported higher odds of a lifetime substance use problem (AOR = 1.98), suicidal ideation (AOR = 1.96), and suicide attempts (AOR = 2.22) than sexual minority women who did not report any history of victimization. When accounting for LGBT-based victimization, sexual minority women who reported lifetime substance use problems reported higher odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 3.25) and suicide attempts (AOR = 5.03). The odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 1.75) and suicidal attempts (AOR = 1.87) related to LGBT-based victimization decreased while accounting for the mediating effects of substance use problems. Sobel tests indicated that substance use problems partially mediated the relationship between LGBT-based victimization and suicidal ideation (t = 2.44, SE = 0.02, p < .05) and between LGBT-based victimization and suicide attempts (t = 2.6, SE = 0.03, p < .01).

Sexual minority men

Sexual minority men who reported experiencing LGBT-based victimization reported higher odds of a lifetime substance use problem (AOR = 2.44), suicidal ideation (AOR = 2.20), and suicide attempts (AOR = 2.39) than sexual minority men who did not report any history of victimization. When accounting for LGBT-based victimization, sexual minority men who reported lifetime substance use problems reported higher odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 4.24) and suicide attempts (AOR = 3.84). The odds of suicidal ideation (AOR = 1.82) and suicidal attempts (AOR = 1.91) related to LGBT-based victimization decreased while accounting for the mediating effects of substance use problems. Sobel tests indicated that substance use problems partially mediated the relationship between LGBT-based victimization and suicidal ideation (t = 6.25, SE = 0.02, p < .001), but was not a significant mediator between LGBT-based victimization and suicide attempts (t = 5.27, SE = 0.02, p > .05).

Discussion

This is the first study of which we are aware to identify substance use as a partial mediator of the relationship between LGBT specific stress and increased odds of suicidality in a large and diverse LGBT patient sample. These findings are particularly relevant as they may suggest that substance use problems are one of the mechanisms relating LGBT-specific victimization to suicidality. Furthermore, our results are consistent with and extend prior research demonstrating that LGBT-victimization and substance use problems are related to increased suicide risk (e.g., Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Meyer, 2003; Savin-Williams, 1994). The results of our study build on this important work and provide more updated findings.

We found that LGBTs who experience victimization are more likely to report lifetime substance use problems. Substances can be utilized to regulate negative affect and tension (e.g., Cooper et al., 1995). Thus, this finding potentially indicates that substances might be a temporary but deleterious coping resource that LGBT individuals utilize in response to the negative feelings and experiences triggered by LGBT-based victimization. Concomitantly, developing a problem with substance use leads to serious suicide risk, as demonstrated by our findings that self-reported lifetime problems with substance use is related to significantly greater risk for suicidal ideation and attempt. Thus, substance use problems might be one potential pathway that mediates the risk effects of minority stress on suicidality.

Our findings underscore the need for culturally sensitive services and interventions for LGBT individuals. For instance, a survey conducted with LGBT-based substance use problems treatment programs found that only 7.4% of those programs provided specific services tailored to LGBT clients whereas 70.8% of the programs provided services that were similar to the general population (Cochran, Peavy, & Robohm, 2007). Clinical services for LGBTs may benefit from being placed within the context of minority stress and its impact on health.

Our results were nuanced by gender. Substance use problems were a consistent mediator for the aggregate sample and the stratified sexual minority women sample. For sexual minority men, however, substance use problems mediated the risk effects of LGBT-based victimization on suicidal ideation but not on suicidal attempts. It is conceptually unclear why this finding exists, but it is important to further investigate and understand in future research. Although this mediation process was not significant, it is pertinent to note that substance use problems were still related to three times greater risk of suicidal attempt for this subpopulation, while accounting for victimization. Thus, despite the non-significant mediation finding, it is important to research and clinically assess the dangerous effects of substance use problems on suicidality for all sexual minorities.

The study results are most appropriately interpreted within the context of the limitations of the study's cross sectional design. All study assessments were completed at the same time period. As such, neither causality nor the directionality of the findings can be inferred. Alternative pathways or reverse relationships cannot be ruled out with certainty. However, such relationships would provide for unclear results that are not theoretically or conceptually grounded. Moreover, study participants were patients of a single New England community health center which may limit the generalizability of study's findings to other patients.

Additionally, participant assessment was through a brief patient questionnaire with each content area measured through one or two items only. Our questionnaire was brief because it was designed to be integrated into a primary care setting; as a result, the findings suffered from response biases (e.g., patient may have been reluctant to disclose or share traumatic information, they might have been pre-occupied with their medical visit). Therefore, assessment of distress, mental health, and substance use fell well short of clinician or diagnostic levels of assessment. Specifically, variables used in the study were based upon self-report dichotomous items, which limited the clinical and culturally sensitive assessment of suicidality and substance use problems (e.g., types of substances) for LGBTs. Similarly, our LGBT-based victimization index was a combination of verbal and physical, and it is limited in discerning the unique negative effects of each. Also, the measure lacked in the comprehensive examination of other forms of LGBT-based victimization, such as subtle-forms of discrimination, severity and type of victimization, as well as other forms of sexual minority stress (e.g., internalized homophobia). It is also limited in its self-report method as well as capturing structural forms of oppression (Schwartz & Meyer, 2010).

Furthermore, our study was limited because we aggregated sexual and gender minorities and did not test for differences in age. Due to differences in experiences of minority stress and health for varying sexual minority groups (e.g., Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, Stirratt, 2009; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012), researchers should examine sexual minority within-group differences (e.g., bisexuals) and understand the impact of multiple intersecting identities in these health disparities (e.g., sexual minorities of color). Moreover, gender minorities were aggregated with the total sample analyses and, due to the small sample size, were not included in the stratified gender analyses. More research is needed to examine the unique experiences of transgender individuals as they have greater risk for discrimination and suicidality (Haas et al., 2011; Grossman & D'Augelli, 2008). Additionally, age of first same-sex attraction has been found to be related to suicidality (Mustanksi & Liu, 2012); thus, future research should examine the effects of age and how it relates to suicide.

The results of the study have additional implications for future research. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine the casual mediating pathways examined in the present study. Other mediating factors may help explain these relationships (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Processes such as substance use expectancies (e.g., using substances to reduce tension reduction) may explain substance misuse vulnerabilities in relation to sexual minority stress (McKirnan & Peterson, 1988). Moreover, more research is needed to examine protective or resilience promoting factors and how they relate to suicide.

The present study responds to calls for research addressing LGBT health disparities (Haas et al., 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2011). In order to advance LGBT health research, researchers must continue to understand the deleterious effects of minority stress on suicide as well as factors that mediate or moderate these relations. These efforts can help inform and advance policies, clinical services, and prevention programs in ameliorating LGBT individuals' risk for suicide.

Contributor Information

Ethan H. Mereish, Boston College, Counseling, Developmental, and Educational Psychology, Campion Hall 309, 140 Commonwealth Avenue, Chestnut Hill, 02467 United States.

C O'Cleirigh, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Psychiatry, 1 Bowdoin Square BS-07B, Boston, 02130 United States.

Judith B. Bradford, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Center for Population Research in LGBT Health, Boston, United States

References

- Amadio DM. Internalized heterosexism, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social science research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaj RP. Substance abuse, internalized homophobia, and gay men and lesbians. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2000;3:5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51:53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Lifetime prevalence of suicide symptoms and affective disorders among men reporting same-sex sexual partners: Results from NHANES III. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:573–578. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:647–658. doi: 10.1037/a0016501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Peavy KM, Robohm JS. Do specialized services exist for LGBT individuals seeking treatment for substance misuse? A study of available treatment programs. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:161–176. doi: 10.1080/10826080601094207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51:53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, Sell RL, Sember R, Silenzio VM, Tierney R. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Findings and concerns. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 2000;4:101–151. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, Oei T. Alcohol and tension reduction. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2008;37:527–537. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D'Augelli AR, et al. Clayton PJ. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality. 2011;58:10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychology Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Erickson SJ. Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology. 2008;27:455–462. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Psychological sequelae of hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:945–951. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Matthews AK, Razzano L, Aranda F. Psychological distress in African American lesbian and heterosexual women. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2002;7:51–68. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:142–167. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, et al. Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70–78. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets VA. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Peterson PL. Stress, expectancies, and vulnerability to substance abuse: A test of a model among homosexual men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:461–466. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Liu RT. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Verbal and physical abuse as stressors in the lives of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths: Associations with school problems, running away, substance abuse, prostitution, and suicide. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:261–269. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Meyer IH. Mental health disparities research: The impact of within and between group analyses on tests of social stress hypotheses. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]