Abstract

Background

Most patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are prescribed antibiotics in general practice. However, there is little evidence that antibiotics bring any value to the treatment of most RTIs. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing may reduce antibiotic prescribing.

Aim

To systematically review studies that have examined the association between point-of-care (POC) C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for RTIs in general practice.

Design and setting

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies.

Method

MEDLINE® and Embase were systematically searched to identify relevant publications. All studies that examined the association between POC C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for patients with RTIs were included. Two authors independently screened the search results and extracted data from eligible studies. Dichotomous measures of outcomes were combined using risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) either by fixed or random-effect models.

Results

Thirteen studies containing 10 005 patients met the inclusion criteria. POC C-reactive protein testing was associated with a significant reduction in antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation (RR 0.75, 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.83), but was not associated with antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period (RR 0.85, 95% CI = 0.70 to 1.01) or with patient satisfaction (RR 1.07, 95% CI = 0.98 to 1.17).

Conclusion

POC C-reactive protein testing significantly reduced antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation for patients with RTIs. Further studies are needed to analyse the confounders that lead to the heterogeneity.

Keywords: antibiotic prescribing, meta-analysis, point-of-care C-reactive protein testing, primary care, respiratory tract infections

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are among the most common acute conditions leading to patients seeking consultations in general practice.1 About 80% of patients with RTIs are prescribed antibiotics.2 However, RTIs are most often self-limiting and seldom require antibiotics for treatment.3 The increased use of antibiotics is significantly associated with the development of drug-resistant bacteria. Clinical guidelines do not support routine antibiotic treatment for patients with RTIs.4

Diagnostic uncertainty often leads to increased inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.5,6 C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acknowledged biomarker to diagnose bacterial infection. The level of CRP can be measured by point-of-care (POC) testing, which is easy to perform in general practice. The robustness and accuracy of POC CRP testing have been proved by many diagnostic studies.7–9 POC CRP testing plays an important role in decreasing diagnostic uncertainty and guiding antibiotic treatment decisions.

To examine the impact of CRP measurement on antibiotic prescribing in patients with RTIs, many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies have been conducted.10–13 However, they did not reach consistent conclusions. For example, Bjerrum et al10 and Cals et al13 concluded that POC CRP testing significantly reduced antibiotic prescribing for patients with RTIs. However, Gonzales et al11 found there was no difference in antibiotic prescribing between POC CRP tested and control patients. In addition, these studies had small sample sizes and thus lacked a more convincing statistical power to clarify whether the use of POC CRP testing in general practice can reduce antibiotic prescribing.

This article describes a systematic review and meta-analysis that were conducted to study the association between family physician use of POC CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing for RTIs in general practice.

METHOD

Eligibility

Studies were included that examined patients who had been diagnosed with RTIs; and compared the antibiotic prescribing rate of a POC CRP testing group with a no-POC CRP testing group. Studies were included if they were RCTs (including parallel-group RCTs, cluster RCTs, crossover RCTs, and factorial RCTs) or observational studies.

Literature search

Literature searches were conducted on 6 June 2013 using the electronic databases MEDLINE® (1946 to present) and Embase (1980 to present). Appendix 1 shows the search terms used.

How this fits in

This study is the first to investigate the relationship between point-of-care C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections. The results indicate that point-of-care C-reactive protein testing significantly reduces antibiotic prescribing for patients with respiratory tract infections.

Selection of studies

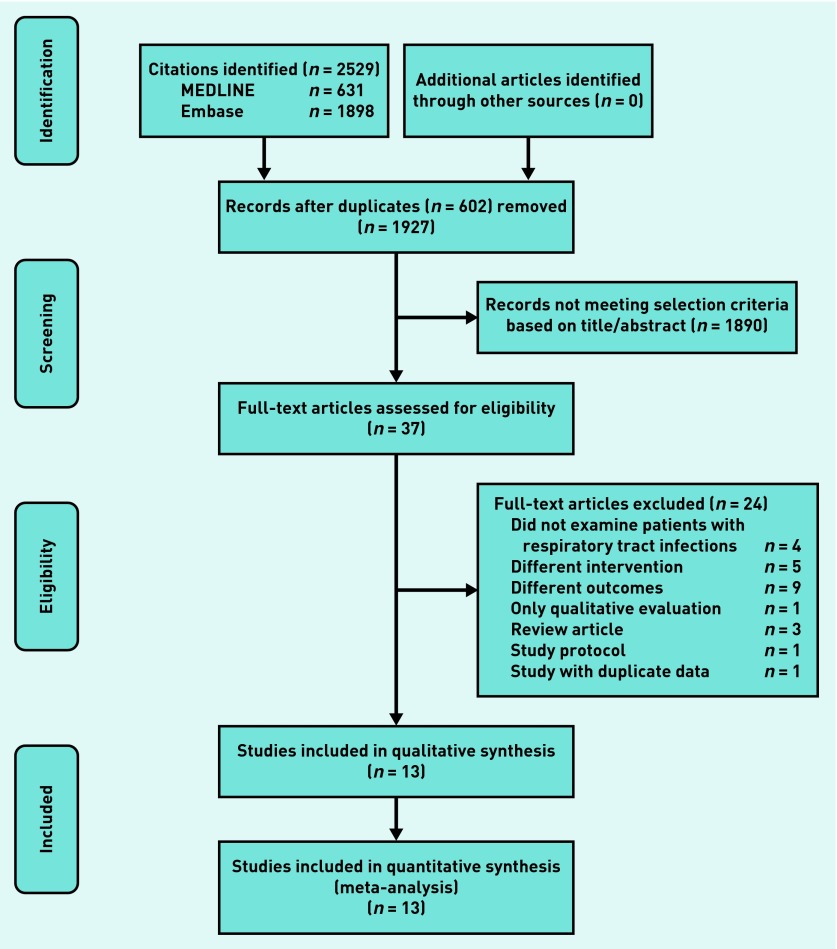

Two authors independently evaluated the articles for inclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by further discussion and consultation from a third author. The selection process by means of a flow chart is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction form was used. The following information was extracted: first author name, publication year, setting, study design, age, sex, location of RTIs, sample size (POC CRP testing/no-POC CRP testing) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Publication year | Setting | Study design | Mean age, years | Female sex, (%) | Location of RTI lower RTI (%) | Sample size (CRP testing/no CRP testing) | NOS score for OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjerrum et al10 | 2004 | Denmark | OS | NA | NA | 0 (0)a | 281/86 | 7 |

| Cals et al20 | 2009 | Netherlands | Cluster RCT | 49.8 | 265 (61.5) | 431 (100) | 227/204 | NA |

| Cals et al13 | 2010 | Netherlands | Parallel-group RCT | 44.3 | 179 (69.4) | 107 (41.5) | 129/129 | NA |

| Cals et al19 | 2011 | Netherlands | Cluster RCT | 48.5 | 135 (58.7) | 230 (100) | 110/120 | NA |

| Cals et al21 | 2013 | Netherlands | Cluster RCT | 49.9 | 235 (62.0) | NA | 203/176 | NA |

| Diederichsen et al25 | 2000 | Denmark | Parallel-group RCT | 37.0 | 465 (57.3) | NA | 414/398 | NA |

| Fagan18 | 2001 | Norway | OS | NA | NA | NA | 122/202 | 6 |

| Gonzales et al11 | 2011 | US | Parallel-group RCT | NA | 86 (65.6) | 88 (67.2) | 69/62 | NA |

| Jakobsen et al22 | 2010 | Norway | OS | NA | 438 (87.1) | NA | 372/131 | 7 |

| Kavanagh et al24 | 2011 | Ireland | OS | NA | NA | NA | 60/60 | 6 |

| Llor et al23 | 2012a | Spain | OS | NA | NA | 5385 (100) | 545/4840 | 6 |

| Llor et al12 | 2012b | Spain | OS | 39.8 | 543 (65.0) | 0 (0)a | 208/628 | 6 |

| Melbye et al26 | 1995 | Norway | Parallel-group RCT | NA | NA | 229 (100) | 108/121 | NA |

All patients had upper respiratory tract infections. CRP = C-reactive protein. NA = not applicable. NOS = Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. OS = observational study. RCT = randomised controlled trial. RTI = respiratory tract infection.

The primary outcome of interest was antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation, which was defined as those patients using antibiotics immediately and those filling a delayed prescription.13 The secondary outcomes were antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period and patient satisfaction.

Assessment of risk of bias

The risk of bias for the included RCTs and observational studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias14 and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale,15 respectively. Two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of studies. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author.

Statistical analysis

Heterogeneity was quantified by means of I2, with a predefined significance threshold of 40%.16 If a significant trend for heterogeneity was observed, a random effect model via generic inverse variance weighting was used to combine the effect. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used to calculate the pooled effects.17 Results were expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous variables. Results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05. Revman software (version 5.2) was used. This software was available through the Cochrane Collaboration.

Subgroup analyses were carried out for the primary outcome with study design (parallel-group RCTs, cluster RCTs and observational studies) and location of RTIs (upper RTIs and lower RTIs). Sensitivity analyses were also performed for the primary outcome to restrict the analyses to European studies and to restrict the analyses to English language studies. No protocol of the present review has been published or registered.

RESULTS

Literature search

A total of 2529 citations were identified. After excluding 602 duplicate records, two authors screened 1927 titles and abstracts to identify the potentially relevant studies. In total 37 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 13 studies were included in qualitative synthesis,10–13,18–26 and subsequently all 13 studies met the final eligibility criteria for meta-analysis. The detailed selection process is outlined in Figure 1.

Description of studies

There were 13 studies with a total of 10 005 patients with RTIs,10–13,18–26 which studied the association between POC CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing. Of the 13 included studies, four studies were conducted in the Netherlands,13,19–21 three in Norway,18,22,26 two in Denmark,10,25 two in Spain,12,23 one in Ireland,24 and one in the US.11 Four studies were parallel-group RCTs.11,13,25,26 Three studies were cluster RCTs.19–21 Six studies were observational studies.10,12,18,22–24Table 1 summarises the basic characteristics of the included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias

Complete risk of bias assessment was performed for all studies. The six observational studies were scored using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale:10,12,18,22–24 four studies got six stars,12,18,23,24 and two studies got seven stars10, 22 (Table 1). Results of the assessment for the seven RCTs (four parallel-group RCTs and three cluster RCTs) are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The risk of bias of included RCTs and cluster RCTs

| Studies | Year | Selection bias | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias | Other bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Anything else, ideally prespecified | ||

| Cals et al20 | 2009 | H | H | H | U | L | L | U |

| Cals et al13 | 2010 | U | U | H | U | L | L | U |

| Cals et al19 | 2011 | H | H | H | U | L | L | U |

| Cals et al21 | 2013 | H | H | H | U | L | L | U |

| Diederichsen et al25 | 2000 | U | U | H | U | U | L | U |

| Gonzales et al11 | 2011 | L | L | H | U | L | L | U |

| Melbye et al26 | 1995 | U | U | H | U | U | L | U |

H = high risk of bias. L = low risk of bias. U = unclear risk of bias.

Antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation

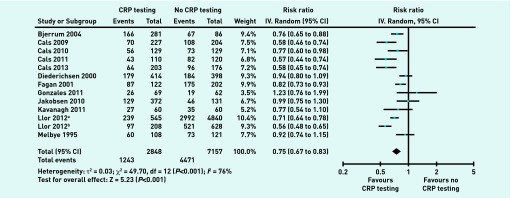

All the 13 studies provided information on antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation to calculate the overall effect size.10–13,18–26 Twelve of these studies reported a decreased antibiotic prescribing rate in the POC CRP testing group.10,12,13,18–26 Eight of them were significant.10,12,13,18–21,23 Pooling of the mean proportion showed that 43.6% of patients with RTIs in the POC CRP testing group and 62.5% of patients with RTIs in the no-POC CRP testing group were prescribed antibiotics. The meta-analysis showed that POC CRP testing was associated with a significant reduction in antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation (RR 0.75, 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.83; P<0.001 for heterogeneity; I2 = 76%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation. IV = inverse variance.

Antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period

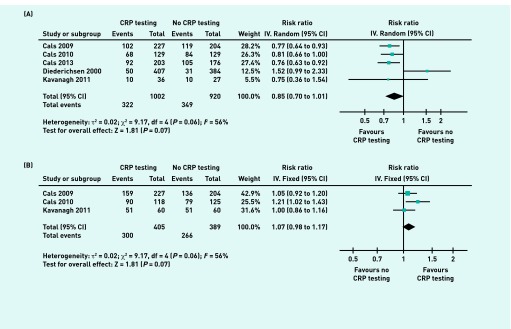

Five studies provided information on antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period, with a total of 1922 patients with RTIs to calculate the overall effect size.13,20,21,24,25 Four of these studies showed a decreased antibiotic prescribing rate in the POC CRP testing group.13,20,21,24 Two of them were significant.20,21 Pooling of the mean proportion showed that 32.1% of patients in the POC CRP testing group and 37.9% of patients in the no-POC CRP testing group were prescribed antibiotics. The meta-analysis showed a non-significant effect on antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period (RR 0.85, 95% CI = 0.70 to 1.01; P = 0.06 for heterogeneity; I2 = 56%) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period and patient satisfaction. IV = inverse variance.

Antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction estimated from meta-analysis of RTI patients with point-of-care CRP testing (intervention group) versus no point-of-care CRP testing (control group). (A) Antibiotic prescribing at any time during the 28-day follow-up period. (B) Patient satisfaction.

Patient satisfaction

Three studies reported patient satisfaction, with 794 patients.13,20,24 Two of these studies reported increased patient satisfaction in the POC CRP testing group.13,20 One of them was significant.13 The combined results indicated a non-significant increase of patient satisfaction in the POC CRP testing group (RR 1.07, 95% CI = 0.98 to 1.17; P = 0.24 for heterogeneity; I2 = 30%) (Figure 3B).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed for the primary outcome according to study design (parallel-group RCTs, cluster RCTs and observational studies) and location of RTIs (upper RTIs and lower RTIs). In the subgroup of cluster RCTs, observational studies, patients with upper RTIs and lower RTIs, the overall results all showed significant reductions of antibiotic prescribing in the POC CRP testing group. In the subgroup of parallel-group RCTs, the overall result demonstrated a non-significant reduction of antibiotic prescribing in the POC CRP testing group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of subgroup and sensitivity analyses for antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation

| Subgroup and sensitivity analyses | Number of studies | Weighted estimates, % (95% CI) | Heterogeneity test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup analyses | |||

|

| |||

| 1. Study design | |||

| Parallel-group RCTs | 4 | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.01) | I2 = 13%, P = 0.33 |

| Cluster RCTs | 3 | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.67) | I2 = 0%, P = 0.99 |

| OSs | 6 | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.85) | I2 = 76%, P<0.001 |

|

| |||

| 2. Location of RTIs | |||

| Upper RTIs | 3 | 0.68 (0.54 to 0.84) | I2 = 76%, P = 0.01 |

| Lower RTIs | 5 | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.83) | I2 = 63%, P = 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Sensitivity analyses | |||

|

| |||

| European studies | 12 | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.82) | I2 = 76%, P<0.001 |

|

| |||

| English language studies | 11 | 0.73 (0.64 to 0.82) | I2 = 76%, P<0.001 |

OS = observational study. RCT = randomised controlled trial. RTI = respiratory tract infection.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the robustness of the results, the analyses were restricted to the 12 European studies10,12,13,18–26 and to the English language studies.10–13,19–25 Pooled data from the European studies and pooled data from the English language studies continued to demonstrate a significant reduction of antibiotic prescribing in the POC CRP testing group (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This meta-analysis comprehensively summarised the current evidence from 13 studies on the association between POC CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing for RTIs in general practice. POC CRP testing was found to significantly decrease antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation. Although there was significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis, results from the sensitivity analysis were consistent, which strengthened the robustness of the conclusion.

Strengths and limitations

Patients with upper RTIs and patients with lower RTIs were included in the analysis. The meta-analysis of primary outcome included 13 eligible studies. A previous systematic review that studied the association between POC CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing only included patients with lower RTIs and identified five studies.27 Comprehensive search strategies were performed to identify relevant studies. The search was not restricted to English language articles. Two grey literature articles18,26 were identified from non-English language journals and were included in the analyses.

Due to limitations of time, money and human resources, the meta-analysis was based on aggregated data extracted from the published full-text articles, rather than individual patient data requested from the researchers of the eligible studies. Meta-analysis that is merely based on aggregated level data has limitations in conducting subgroup analyses.28 It is not always possible to explore the sources of heterogeneity.29 In this study, significant heterogeneity was identified. Although subgroup analyses were conducted according to location of the RTIs and study design, the heterogeneity still existed within subgroups of upper RTIs, lower RTIs, and subgroups of observational studies. Future research needs to collect original data and conduct individual patient meta-analyses to find more potential reasons for the heterogeneity.

Comparison with existing literature

To the authors knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that aims to summarise all the research evidence that has studied the association between POC CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing in patients with RTIs. A systematic review conducted by Engel et al27 concentrated on patients with lower RTIs only. They included both randomised and observational studies. Their results showed that POC CRP testing was associated with a significant reduction in antibiotic prescribing (RR 0.6, 95% CI = 0.5 to 0.7). It is consistent with the subgroup result of lower RTIs in the current study.

Implications for research and practice

For each patient with a RTI, family physicians have to decide whether to prescribe antibiotics for them. POC CRP testing can facilitate RTI consultation and decision making in general practice. If POC CRP is tested and the test result shows that the CRP level is low, it is most likely that the family physician will not prescribe antibiotics for this patient.

Family physicians should be aware of the problems that arise from over-prescription of antibiotics, which may drive antibiotic resistance. Reduced antibiotic prescribing in general practice is associated with reduced local antibiotic resistance.30 The POC CRP test is an office-based and cost-effective test.19,31 There are few limitations for its applicability in general practice. This study has indicated that POC CRP testing in general practice is associated with significant reductions in antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation for patients with RTIs. Further individual patient data meta-analyses and studies with large sample sizes are needed to investigate the potential confounders that lead to the heterogeneity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the National Training Center for General Practice, Ministry of Health China.

Appendix 1.

Search terms

| ID | Search |

|---|---|

| #1 | ((exp Respiratory Tract Diseases/) OR (exp Respiratory Tract Infections/) OR ((respiratory adj3 (infection* or disease* or symptom*)).tw.) OR (exp Sick Building Syndrome/) OR (exp Otitis Media/) OR (exp Common Cold/) OR (exp Influenza, Human/) OR (exp Asthma/) OR (exp Rhinitis/) OR (exp Sinusitis/) OR (exp Cough/) OR (exp pharyngitis/) OR (exp laryngitis/) OR ((laryngotracheobronchit*). ti,ab.) OR (exp tonsillitis/) OR (exp peritonsillar abscess/) OR (exp croup/) OR (exp epiglottitis/) OR ((supraglottit*).ti,ab.) OR ((rhinosinusit*).ti,ab.) OR (exp otitis media/)) |

| #2 | ((C reactive protein).ti,ab.) |

| #3 | ((exp anti-infective agents/) OR (exp anti-bacterial agents/) OR ((anti-biotic* or antibiotic* or anti-infect* antiinfect* or antibacteria* or anti-bacteria*).ab,ti.) OR ((microbicide* or anti-microbi* or antimicrobi* or microbi*).ab,ti.) OR ((beta-lactam* or betalactam* or B-lactam* or aminoglycoside* or vancomycin).ab,ti.)) |

| #4 | (#1 AND #2 AND #3) |

No restriction was placed on the publication language. References were also screened from retrieved articles and reviews to identify additional articles that met the eligibility criteria.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Thorpe JM, Smith SR, Trygstad TK. Trends in emergency department antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(6):928–935. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheij TJ. Prescribing antibiotics for respiratory tract infections by GPs: management and prescriber characteristics. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(511):114–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowbotham S, Chisholm A, Moschogianis S, et al. Challenges to nurse prescribers of a no-antibiotic prescribing strategy for managing self-limiting respiratory tract infections. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(12):2622–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan T, Little P, Stokes T, Guideline Development Group Antibiotic prescribing for self limiting respiratory tract infections in primary care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotwani A, Wattal C, Katewa S, et al. Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):684–690. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold SR, To T, McIsaac WJ, Wang EE. Antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infection: the importance of diagnostic uncertainty. J Pediatr. 2005;146(2):222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk G, Fahey T. C-reactive protein and community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory care: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. Fam Pract. 2009;26(1):10–21. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attia MW. Review: C-reactive protein has moderate diagnostic accuracy for serious bacterial infection in children with fever. Evid Based Med. 2009;14(2):56. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.2.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindbaek M, Hjortdahl P. The clinical diagnosis of acute purulent sinusitis in general practice: a review. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(479):491–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjerrum L, Gahrn-Hansen B, Munck AP. C-reactive protein measurement in general practice may lead to lower antibiotic prescribing for sinusitis. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(506):659–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzales R, Aagaard EM, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. C-reactive protein testing does not decrease antibiotic use for acute cough illness when compared to a clinical algorithm. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llor C, Bjerrum L, Arranz J, et al. C-reactive protein testing in patients with acute rhinosinusitis leads to a reduction in antibiotic use. Fam Pract. 2012;29(6):653–658. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cals JW, Schot MJ, de Jong SA, et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):124–133. doi: 10.1370/afm.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biggerstaff BJ, Tweedie RL. Incorporating variability in estimates of heterogeneity in the random effects model in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1997;16(7):753–768. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970415)16:7<753::aid-sim494>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagan MS. [Can use of antibiotics in acute bronchitis be reduced?] (In Norwegian) Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2001;121(4):455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cals JW, Ament AJ, Hood K, et al. C-reactive protein point of care testing and physician communication skills training for lower respiratory tract infections in general practice: economic evaluation of a cluster randomized trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(6):1059–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cals JW, Butler CC, Hopstaken RM, et al. Effect of point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b1374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cals JW, de Bock L, Beckers PJ, et al. Enhanced communication skills and C-reactive protein point-of-care testing for respiratory tract infection: 3.5-year follow-up of a cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(2):157–164. doi: 10.1370/afm.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakobsen KA, Melbye H, Kelly MJ, et al. Influence of CRP testing and clinical findings on antibiotic prescribing in adults presenting with acute cough in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(4):229–236. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2010.506995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llor C, Cots JM, López-Valcárcel BG, et al. Interventions to reduce antibiotic prescription for lower respiratory tract infections: Happy Audit study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(2):436–441. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00093211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kavanagh KE, O’Shea E, Halloran R, et al. A pilot study of the use of near-patient C-Reactive Protein testing in the treatment of adult respiratory tract infections in one Irish general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diederichsen HZ, Skamling M, Diederichsen A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of CRP rapid test as a guide to treatment of respiratory infections in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18(1):39–43. doi: 10.1080/02813430050202541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melbye H, Aaraas I, Fleten N, et al. [The value of C-reactive protein testing in suspected lower respiratory tract infections. A study from general practice on the effect of a rapid test on antibiotic research and course of the disease in adults.] (In Norwegian) Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1995;115(13):1610–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel MF, Paling FP, Hoepelman AI, et al. Evaluating the evidence for the implementation of C-reactive protein measurement in adult patients with suspected lower respiratory tract infection in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2012;29(4):383–393. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyman GH, Kuderer NM. The strengths and limitations of meta-analyses based on aggregate data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koopman L, van der Heijden GJ, Glasziou PP, et al. A systematic review of analytical methods used to study subgroups in (individual patient data) meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(10):1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler CC, Dunstan F, Heginbothom M, et al. Containing antibiotic resistance: decreased antibiotic-resistant coliform urinary tract infections with reduction in antibiotic prescribing by general practices. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(543):785–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oppong R, Jit M, Smith RD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to inform antibiotic prescribing decisions. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(612):e465–e471. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X669185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]