Abstract

Cystic fibrosis is a systemic disease involving defective mucus secretion in different parts of the body resulting in a wide range of systemic complications. We are presenting the histology of the lacrimal gland from a 25 year old male with cystic fibrosis using light microscopy. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, Lacrimal gland, Tears

Introduction

The tear film is approximately 8–9 μm thick and is comprised of 98.2% water and 1.8% solids. The three layers that make up the tear film are lipid, aqueous and mucous. The (outer) lipid layer consists of phospholipids, cholesterol and wax esters. The phospholipid end of the fatty acids interacts with the aqueous layer while the fatty acid end interacts with other lipids forming a layer 0.1–0.2 μm thick that mitigates evaporation of the tears. The lipid layer is secreted by the meibomian (tarsal) glands and the sebaceous glands of Zeis. The (middle) aqueous layer, provides nutrients to the non-vascularized ocular surface tissue and is secreted by the main and the accessory lacrimal glands. The aqueous layer is 7–8 μm thick consisting of water, electrolytes and glycoproteins. The Na+ concentration of tears is the same as serum, however, the concentration of K+ is 5–7 times greater than that in serum. Na+, K+, and Cl− concentration regulate the osmotic flow of fluids. The (inner) mucous layer is 1 μm thick and acts as a lubricating layer. The mucin layer is composed of high molecular glycoproteins, electrolytes, and water. It is secreted principally by the conjunctival goblet cells, the stratified squamous cells of the conjunctival and corneal epithelium and minimally by the lacrimal glands and their components.1,2

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is inherited as an autosomal trait characterized by defective mucus secretion in different parts of the body. CF is caused by a flaw, or mutation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR gene) occurring at a single locus on the long arm of chromosome 7. The damaged CFTR gene prevents function of the chloride ion channels in patients with CF resulting in excessive salt accumulation in the body, where some of it eventually is excreted through the sweat glands. Hence, salty skin is of diagnostic value in CF. As water follows salt movement, the predicted net flux of water would be from the lumen to the sub-mucosa and would be greater across CF epithelia. Normal water movement is required to produce thin, free-flowing mucus. The nonfunctioning chloride ion channels resulted in less water in the lumens of the ducts resulting in sticky, thick mucus that CF patients endure.3,4 Since the lacrimal glands contribute to the production of mucus we therefore, expect some changes in the structure of the lacrimal glands. In this report, we present the histological findings in the lacrimal gland of a patient with CF.

Case report

The orbital contents were evaluated of the lacrimal glands of two orbits from a 25 year old white male who died from CF related complications. The patient was diagnosed with CF at 10 months of age by the analysis of duodenal aspirate. The patient’s sister was also reported to suffer from CF. The pathologist report on autopsy of the patient revealed the multisystem involvement of CF including: (1) CF and atrophy of the pancreas, (2) chronic obstructive bronchial disease, (3) dilatation of the right ventricle, (4) passive congestion of the liver, (5) infertility with atrophy of the testis.

The orbital contents of the lacrimal glands were obtained immediately after death from 9 subjects without CF with age ranging between 30 and 60 years. The glands from all subjects were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 h, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned 6–8 μm thick with microtomes. All the sections from all subjects were stained5 with: 1. Hematoxylin–eosin (H&E), which is a popular stain in histology that stains the nuclei blue and the remaining tissue in different shades of red; 2. Periodic acid Schiff stain (PAS), which is a staining method used to detect polysaccharides such as glycogen, and neutral mucosubstance such as glycoproteins, glycolipids and neutral mucins in tissues; 3. Alcian blue stain, which is a copper phthalocyanine, stains acid mucopolysaccharides and glycosaminoglycans – the stained parts are blue to bluish-green. The sections were studied with light microscopy.

Results

By comparing the lacrimal gland from a subject with CF to the glands of normal subjects we observed the following:

-

1.

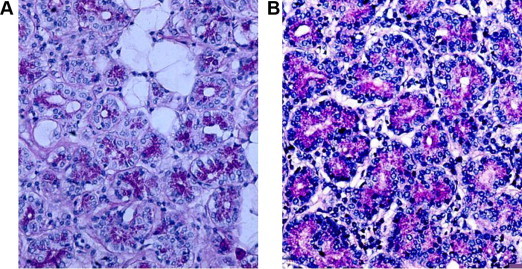

In the lacrimal gland from CF patient there were an increased number and size of vacuoles within the acini and outside the acini, (Fig. 1a and b).

-

2.

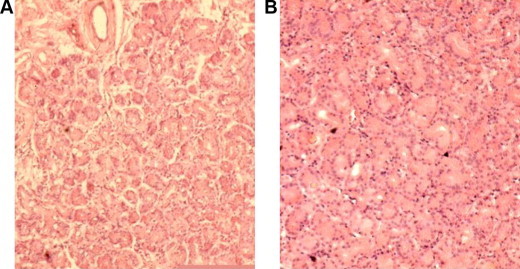

There was a definite decrease in the number of the acini as shown in Fig. 2.

-

3.

There were positive staining in both PAS and Alcian Blue staining in both the normal lacrimal glands and the glands from CF patient.

-

4.

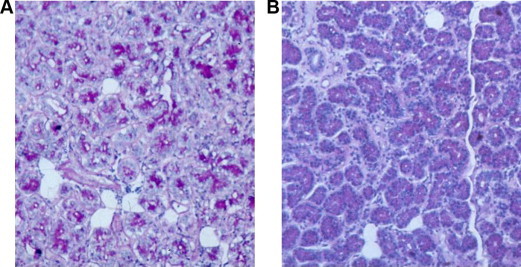

There was a decrease in PAS-stained material in the lacrimal gland from the CF patient compared to the normal lacrimal glands (Fig. 3a and b)

-

5.

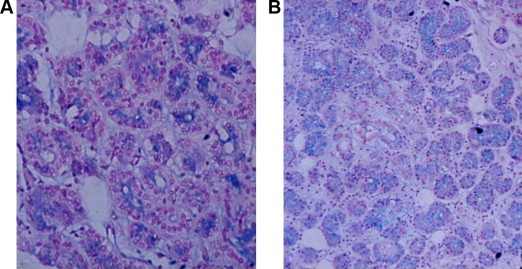

There was a decrease in Alcaine blue-stained material in the lacrimal gland from the CF patient compared to normal lacrimal glands (Fig. 4a and b).

Figure 1.

Section of the lacrimal gland stained with Periodic acid Schiff stain; Note the increase in the number and the size of the vacuoles in the patient with cystic fibrosis (A) as compared with normal patients (B).

Figure 2.

Section from lacrimal glands stained with Hematoxylin–eosin stain. Note the rarefication of the acini in the patient with cystic fibrosis (A) as compared with normal patients (B).

Figure 3.

Section from lacrimal glands stained with Periodic acid Schiff stain; note the decrease in the amount of the stained material and increase in the vacuoles (A) in patients with cystic fibrosis compared with normal patients (B).

Figure 4.

Section from lacrimal gland from a patient with cystic fibrosis (A) stained with Alcian blue. Note the decrease in the stained material as compared with the section from normal patients (B).

Discussion

In the present case; the patient’s sister was affected with CF; which goes with the known pattern of inheritance of the disease. In this comparison of the histopathology, of the lacrimal gland of one CF patient to a number of normal lacrimal gland samples we found some differences. There was a decrease in the PAS stained material as well as a decrease in the Alcaine blue stained material compared to normal. This may indicate that glycoprotein is a part of the lacrimal secretion and the decrease of this material in this patient might be primary or secondary to the complication of CF. The disturbance in chloride channels disrupted Na+ movement and subsequently water movement from the duct lumen to the submucosa causing the mucus in the lumen to thicken, clogging the small ducts within the lacrimal glands resulting in the degeneration of the acini. This is the likely explanation of the decrease in the acini and the presence of vacuoles noted in the present case and a previous report.6 Orzalesi6 in 1971 reported the presence of vacuoles and droplets which increase with age in the orbital section of normal human lacrimal glands. The vacuoles were large and numerous in our patient despite his young age. These vacuoles may contain fluid or fat lost during tissue processing. There was a decrease in glycoprotein (PAS and Alcaine blue positive material) which is likely secondary to the degenerative process of the acini.7

We expect CF may affect different ocular structures8–21 based on the following observations: (1) CFTR activity was demonstrated in the conjunctiva8 and the epithelial cells in the lacrimal gland ducts9; (2) In CF, conjunctival goblet cells were reported to be normal in some studies,10 and decreased in other studies.11 This difference may be related to the stage of the disease at the time of observation. Therefore the tear film is affected in CF. Patients with CF are expected to have an abnormal tear film and punctate keratitis. An abnormal tear breakup time12 and hypo-secretion of tear fluid13 have been previously reported in CF patients. It is therefore likely that the degenerative process (decreased acini and increased size and number of vacuoles) contributes to the decrease in tear secretion. Hence the stability of the tear film will be affected. Other mechanisms to explain the punctate keratitis in CF patients include high calcium levels which induce the precipitation of glycoprotein of tear as suggested for other glands.14 This decrease in water solubility of mucin causes instability of the tear film, which may lead to superficial punctate keratitis. Tissue culture findings suggest that metabolic error is going on in all the cells of the body though it gives rise to clinical manifestation in exocrine glands.

CF is a systemic disease with abnormal NaCl movement contributing to the production of thick, sticky mucus that clogs the secretory channels and damages various organs. The eye may also be affected indirectly. The thick secretion will clog the biliary and pancreatic ducts resulting in cirrhosis and impaired pancreatic function as seen in the present case. Both liver and pancreatic complications of this disease may cause repeated gastrointestinal disturbances such as diarrhea, constipation, diabetes, mal-absorption and mal-nutrition. Mal-absorption will cause vitamin A deficiency which may result in night blindness and xerophthalmia that are responsive to vitamin A treatment.15–17 In 1998 Suttle et al.18 reported an abnormal visual evoked potential and electroretinogram in patients with CF. Gorden et al.,19 reported the presence of drusen involving the macula. Schupp et al20 reported that adults with CF have dramatically low serum and macular concentrations of carotenoids (lutein and zeaxanthin), which may explain the previous macular involvement.

As in the present case the bronchioles may get clogged leading to repeated respiratory infection and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease resulting in polycythemia and subsequent retinal vein occlusion.21 The reproductive system may be affected especially in males (as in the present case) with infertility and atrophy of the testis may be secondary to clogging of the vas deferens. However, females with CF may become pregnant because the tubes are wider. Other CF common complications include nasal polyps of unknown etiology and sinusitis which might be due to the thick mucus.

In summary different ocular tissues may be affected by CF either directly or indirectly. In the light of these findings the lacrimal gland is being affected by this disease which can manifest on the ocular surface. Therefore we recommend that patients with CF should be evaluated for tear deficiency and tear stability.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University.

References

- 1.Egeberg J., Jensen O.A. The ultrastructure of the acini of the human lacrimal glands. Acta ophthalmol. 1969;47:400. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1969.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basic clinical and science course in Ophthalmology. Section 2. Fundamentals and the principles of ophthalmology American Academy of, Ophthalmology 2012.

- 3.Thomas F Boat: cystic fibrosis; chapter 393; in Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 17th edition (May 2003): by Richard E., Md. Behrman (Editor), Robert M., Md. Kliegman (Editor), Hal B., Md. Jenson (Editor) By W B Saunders.

- 4.Sharon Giddings. Chelsea House Publishers; 2009. Genes & disease cystic fibrosis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston D.A., Reid R., Burt A.D., Harrison D.J., Fleming S., editors. Muir’s text book of pathology. 14th edition. Book Power Publisher; 2008. p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orzalesi N. The structure of human lacrimal gland. Micr Cytol. 1971;3:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arlen R. The effect of parathyroid hormone on incorporation of 3H-glucosamine into hyaluronic acid in bone organic culture. Endocrinology. 1973;92(4):1282–1285. doi: 10.1210/endo-92-4-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner H.C., Bernstein A., Candia O.A. Presence of CFTR in the conjunctival epithelium. Curr Eye Res. 2002 Mar;24(3):182–187. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.24.3.182.8297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu M., Ding C. CFTR-mediated Cl-transport in the acinar and duct cells of rabbit lacrimal gland. Curr Eye Res. 2012 May;(11) doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.675613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm K., Kessing S.V. Conjunctival goblet cells in patients with cystic fibrosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 1975 Mar;53(2):167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1975.tb01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mrugacz M., Kasacka I., Bakunowicz-Lazarczyk A., Kaczmarski M., Kulak W. Impression cytology of the conjunctival epithelial cells in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eye (Lond) 2008 Sep;22(9):1137–1140. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall D.S., Goyal S. Cystic fibrosis presenting with corneal perforation and crystalline lens extrusion. J R Soc Med. 2010 Jul;103(Suppl 1):S30–3. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.s11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mrugacz M., Bakunowicz-łazarczyk A., Minarowska A., Zywalewska N. Evaluation of the tears secretion in young patients with cystic fibrosis. Klin Oczna. 2005;107(1–3):90–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DI Saint’ Agnese P.A., Grossman H., Darling R.C., Denning C.R. Saliva, tears and duodenal contents in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. Pediatrics. 1958 Sep;22(3):507–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi D., Dhawan A., Baker A.J., Heneghan M.A. An atypical presentation of cystic fibrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008 Jun;12(2):201. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindenmuth K.A., Del Monte M., Marino L.R. Advanced xerophthalmia as a presenting sign in cystic fibrosis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989 May;21(5):189–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha A., Jonas J.B., Kurlkarni M., Nangia V. Vitamin A deficiency in schoolchildren in urban central India: The central India children eye study. Arch Ophthamol. 2011 Aug;129(8):1093–1094. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suttle C.M., Harding G.F. The VEP and ERG in a young infant with cystic fibrosis. A case report. Doc Ophthalmol. 1998;95(1):63–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1001772327537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goren J.F., Shah S.P., Janzen G.P., Gross N.E., Duker J.S. Diffuse retinal pigment epithelial disease in an adult with cystic fibrosis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011 Jun;9:42. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110602-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schupp C., Olano-Martin E., Gerth C., Morrissey B.M., Cross C.E., Werner J.S. Lutein, zeaxanthin, macular pigment, and visual function in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Jun;79(6):1045–1052. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruce G.M. The eye and cystic fibrosis of the pancreas: a resume. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1964;62:123–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]