Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the number, types, and locations of oral mucosal lesions in patients who attended the Admission Clinic at the Kuwait University Dental Center to determine prevalence and risk factors for oral lesions.

Subjects and methods

Intraoral soft tissue examination was performed on new patients seen between January 2009 and February 2011. The lesions were divided into six major groups: white, red, pigmented, ulcerative, exophytic, and miscellaneous.

Results

Five hundred thirty patients were screened, out of which 308 (58.1%) had one or more lesions. A total of 570 oral lesions and conditions were identified in this study, of which 272 (47.7%) were white, 25 (4.4%) were red, 114 (20.0%) were pigmented, 21 (3.7%) were ulcerative, 108 (18.9%) were exophytic, and 30 (5.3%) were in the miscellaneous group. Overall, Fordyce granules (n = 116; 20.4%) were the most frequently detected condition. A significantly higher (p < 0.001) percentage of older patients (21–40 years and ⩾41 years) had oral mucosal lesions than those in the ⩽20 years age group. A significantly higher (p < 0.01) percentage of smokers had oral mucosal lesions than did nonsmokers. Most of the lesions and conditions were found on the buccal mucosa and gingiva.

Conclusions

White, pigmented, and exophytic lesions were the most common types of oral mucosal lesions found in this study. Although most of these lesions are innocuous, the dentist should be able to recognize and differentiate them from the worrisome lesions, and decide on the appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Oral mucosa, Oral lesions, Prevalence, Kuwait, Screening, Tobacco use

1. Introduction

The oral mucosa serves as a protective barrier against trauma, pathogens, and carcinogenic agents. It can be affected by a wide variety of lesions and conditions, some of which are harmless, while others may have serious complications (Langlais et al., 2009). Identification and treatment of these pathologies are an important part of total oral health care. Hence, oral soft tissue examination is crucial, and it should be done in a systematic manner to include all parts of the oral cavity.

There are several studies from around the world on the prevalence of biopsied oral mucosal lesions (Ali and Sundaram, 2012; Carvalho Mde et al., 2011; Franklin and Jones, 2006). These studies do not represent all the lesions seen by dentists, since certain conditions such as hairy tongue, geographic tongue, Fordyce granules, chronic cheek biting, leukoedema, herpes simplex infections, and recurrent aphthous ulcers are rarely biopsied. Other studies have determined the overall prevalence of oral soft tissue lesions found during clinical examination and followed by biopsy when necessary (Byakodi et al., 2011; Cadugo et al., 1998; Kovac-Kovacic and Skaleric, 2000; Martínez Díaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Mehrotra et al., 2010; Pentenero et al., 2008). There is a paucity of such studies from Kuwait.

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients attending the Admission Clinic at the Kuwait University Dental Center (KUDC). This information can help determine the epidemiology and severity of oral lesions in Kuwait, and help identify risk factors for oral lesions. It will also serve as a baseline for future studies with the goal of finding ways to improve oral health in this country.

2. Subjects and methods

The Faculty of Dentistry of Kuwait University is the only dental school in Kuwait, and the KUDC offers free dental services to the general public. The present study was conducted on new patients attending the KUDC Admission Clinic between January 2009 and February 2011. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kuwait University. Informed consent was obtained from patients participating in the study.

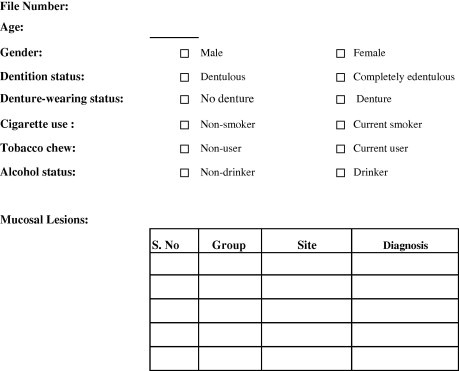

A screening examination including intraoral clinical exam was performed by an oral pathologist from the Department of Diagnostic Sciences using artificial light, dental mirror, dental explorer, gauze, and other materials as described (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Byakodi et al., 2011; Campisi and Margiotta, 2001). Personal data including age, gender, chief complaint, and social habits were recorded (Fig. 1). Using the Color Atlas of Common Oral Diseases (Langlais et al., 2009) as a guide for diagnosis and grouping, oral mucosal lesions were identified as either white, red, pigmented, ulcerative, or exophytic based on their prominent clinical appearance. Lesions that did not fit in any of the above groups were labeled miscellaneous. Cytologic smears were obtained when necessary and lesions which required histopathological confirmation were referred to the oral surgery clinic for biopsy. After biopsy, the lesion was added to one of the six groups based on the clinical appearance of the lesion.

Figure 1.

Data collection sheet.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The normal Z-test for proportions was used to compare the prevalence of the lesions based on the characteristics of age, gender, tobacco use, alcohol use, dentition, and denture wearing status, using GraphPad software (GraphPad, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). A p value of ⩽0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The demographic characteristics of the 530 patients in this study are shown in Table 1. Of the 530 patients, 308 (58.1%) had one or more lesions (174 males and 134 females). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of oral lesions between males (174/292; 59.6%) and females (134/238; 56.3%). A statistically significantly greater percentage of older patients had one or more oral lesion than patients ⩽20 years (p < 0.001). Seventy-one percent (147/207) of patients 21–40 years of age and 61.8% (134/217) of patients ⩾41 years old had one or more oral mucosal lesions. Only 25.5% (27/106) of patients ⩽20 years of age had oral lesions (Table 1). A significantly higher (p < 0.01) percentage of smokers (68/97; 70.1%) had oral mucosal lesions than did nonsmokers (240/433; 55.4%). All alcohol users (8/8; 100%) and all tobacco chewers (5/5; 100%) had oral mucosal lesions, a significantly higher (p < 0.001) percentage than that of nonusers of alcohol (300/522; 57.5%) and chewing tobacco (303/525; 57.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the patients in the study sample. (N = 530).

| Background characteristic | Patients screened (N = 530) | Patients with lesions (n = 308) (%)+ |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 292 | 174 (59.6) |

| Female | 238 | 134 (56.3) |

| Age group | ||

| ⩽20 years | 106 | 27 (25.5) |

| 21–40 years | 207 | 147 (71.0)⁎⁎ |

| ⩾41 years | 217 | 134 (61.8)⁎⁎ |

| Dentition & denture-wearing status | ||

| Completely/partially dentulous | 519 | 299 (57.6) |

| With denture | 38 | 25 (65.8) |

| Without denture | 481 | 274 (57.0) |

| Completely edentulous | 11 | 9 (81.8) |

| With denture | 8 | 7 (87.5) |

| Without denture | 3 | 2 (66.7) |

| Cigarette use | ||

| Non-smoker | 433 | 240 (55.4) |

| Current smoker | 97 | 68 (70.1)⁎ |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Non-user | 522 | 300 (57.5) |

| Occasional | 8 | 8 (100.0)⁎⁎ |

| Tobacco chewing | ||

| Non-chewer | 525 | 303 (57.7) |

| Current chewer | 5 | 5 (100.0)⁎⁎ |

p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

Percentage of the number of patients screened in each subcategory.

A total of 570 oral lesions and conditions, 354 in males and 216 in females, were found in the study (Table 2). Two hundred seventy-two (47.7%) lesions were white, 25 (4.4%) were red, 114 (20.0%) were pigmented, 21 (3.7%) were ulcerative, 108 (18.9%) were exophytic, and 30 (5.3%) were in the miscellaneous group. Overall, Fordyce granules (n = 116; 20.4%) were the most frequently detected condition, followed by linea alba (n = 65; 11.4%), generalized pigmentation (n = 64; 11.2%), hairy tongue (n = 32; 5.6%), leukoedema (n = 31; 5.4%), frictional keratosis (n = 30; 5.3%), and irritation fibroma (n = 28; 4.9%).

Table 2.

Frequency of oral mucosal lesions and their distribution according to sex, age and smoking status (N = 570).

| Diagnosis | n (% of total) | Sex |

Age (years) |

Smoking status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 292) | Female (n = 238) | ⩽20 (n = 106) | 21–40 (n = 207) | ⩾41 (n = 217) | Non-smoker (n = 433) | Smoker (n = 97) | ||

| White | ||||||||

| Fordyces granules | 116 (20.4) | 88⁎⁎⁎ | 28 | 6 | 50⁎⁎⁎ | 60⁎⁎⁎ | 86 | 30⁎ |

| Linea alba | 65 (11.4) | 35 | 30 | 7 | 31⁎ | 27 | 55 | 10 |

| Leukoedema | 31 (5.4) | 26⁎⁎ | 5 | 2 | 17⁎ | 12 | 14 | 17⁎⁎⁎ |

| Frictional keratosis | 30 (5.3) | 24⁎⁎ | 6 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 16⁎⁎⁎ |

| Morsicatio Buccarum | 11 (1.9) | 8 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 |

| Lichen planus | 8 (1.4) | 3 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Nicotine stomatitis | 6 (1.1) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5⁎ |

| Tobacco pouch keratosis | 2 (0.4) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Othersa | 3 (0.6) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 272 (47.7) | |||||||

| Red | ||||||||

| Geographic tongue | 17 (3.0) | 9 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 4 |

| Purpura | 5 (0.9) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Mucosal burn | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Denture stomatitis | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Allergic contact stomatitis | 1 (0.2) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 25 (4.4) | |||||||

| Pigmented | ||||||||

| Generalized pigmentation | 64 (11.2) | 41 | 23 | 4 | 37⁎⁎⁎ | 23⁎ | 40 | 24⁎⁎⁎ |

| Hairy tongue | 32 (5.6) | 24⁎ | 8 | 3 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 18⁎⁎⁎ |

| Amalgam tattoo | 11 (1.9) | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 2 |

| Melanotic macule | 5 (0.9) | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Melanocytic nevus | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 114 (20) | |||||||

| Ulcerative | ||||||||

| Traumatic ulcer | 12 (2.1) | 8 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 3 |

| Recurrent Herpes Simplex | 6 (1.1) | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 21 (3.7) | |||||||

| Exophytic | ||||||||

| Irritation fibroma | 28 (4.9) | 12 | 16 | 2 | 11 | 15 | 26 | 2 |

| Torus/exostoses | 21 (3.7) | 9 | 12 | 0 | 14 | 7 | 17 | 4 |

| Frenal tag | 14 (2.5) | 8 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 3 |

| Parulis | 11 (1.9) | 3 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| Varicosity | 8 (1.4) | 6 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| Foliate papillitis | 6 (1.1) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Generalized gingival enlargement | 4 (0.7) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mucocoele | 4 (0.7) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Epulis fissuratum | 3 (0.5) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Hemangioma | 2 (0.4) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Localized reactive gingival lesion | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 | |||||

| Othersb | 5 (1.0) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Subtotal | 108 (18.9) | |||||||

| Miscellaneous | ||||||||

| Fissured tongue | 19 (3.3) | 11 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 3 |

| Scalloped tongue | 7 (1.2) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| Ankyloglossia | 4 (0.7) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Subtotal | 30 (5.3) | |||||||

| Total | 570 (100) | 354 | 216 | 40 | 279 | 251 | 406 | 164 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Leukoplakia (1), Lichenoid drug eruption (1), Candidiasis (1).

Periodontal abscess (1), Papilloma (1), Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (1), Ranula (1), Herniated fat pad (1).

The frequency of Fordyce granules, leukoedema, frictional keratosis, and hairy tongue was significantly higher in males than in females (Table 2). Fordyce granules were significantly more (p < 0.001) frequent in older (21–40 years and ⩾41 years) patients than in patients ⩽20 years. Leukoedema and linea alba were more frequent in patients 21–40 years than in patients ⩽20 years (p < 0.05). Generalized pigmentation was more frequent in older (21–40 years and ⩾41 years) patients than in patients ⩽20 years (p < 0.001; p < 0.05, respectively). Interestingly, generalized pigmentation was also found to be more frequent in the 21–40 years patients than in the ⩾41 years patients (p < 0.05). The frequency of Fordyce granules, leukoedema, frictional keratosis, nicotine stomatitis, generalized pigmentation, and hairy tongue was significantly higher in smokers than in nonsmokers (Table 2).

We also noted the location of the 570 lesions and conditions identified. A total of 110 (19.3%) were found on the gingiva, 47 (8.2%) on the lip/labial mucosa, 280 (49.1%) on the buccal mucosa, 98 (17.2%) on the tongue, 5 (0.9%) on the floor of the mouth, and 30 (5.8%) on the palate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Site distribution of oral mucosal lesions (N = 570).

| Diagnosis | Site |

n (% of total)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gingiva | Lip/labial mucosa | Cheek | Tongue | Floor of mouth | Palate | ||

| Fordyces granules | 6 | 110 | 116 (20.4) | ||||

| Linea alba | 1 | 64 | 65 (11.4) | ||||

| Generalized pigmentation | 41 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 64 (11.2) | ||

| Hairy tongue | 32 | 32 (5.6) | |||||

| Leukoedema | 31 | 31 (5.4) | |||||

| Frictional keratosis | 18 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 30 (5.3) | ||

| Irritation fibroma | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 28 (4.9) | |

| Torus/exostoses | 9 | 12 | 21 (3.7) | ||||

| Fissured tongue | 19 | 19 (3.3) | |||||

| Geographic tongue | 17 | 17 (3.0) | |||||

| Frenal tag | 14 | 14 (2.5) | |||||

| Traumatic ulcer | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 12 (2.1) |

| Morsicatio Buccarum | 11 | 11(1.9) | |||||

| Amalgam tattoo | 9 | 1 | 1 | 11 (1.9) | |||

| Parulis | 11 | 11 (1.9) | |||||

| Lichen planus | 8 | 8 (1.4) | |||||

| Varicosity | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 (1.4) | |||

| Scalloped tongue | 7 | 7 (1.2) | |||||

| Nicotine stomatitis | 6 | 6 (1.1) | |||||

| Recurrent Herpes Simplex | 1 | 5 | 6 (1.1) | ||||

| Foliate papillitis | 6 | 6 (1.1) | |||||

| Purpura | 4 | 1 | 5 (0.9) | ||||

| Melanotic macule | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 (0.9) | |||

| Generalized gingival enlargement | 4 | 4 (0.7) | |||||

| Mucocoele | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 (0.7) | |||

| Ankyloglossia | 4 | 4 (0.7) | |||||

| Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis | 2 | 1 | 3 (0.5) | ||||

| Epulis fissuratum | 3 | 3 (0.5) | |||||

| Tobacco pouch keratosis | 2 | 2 (0.4) | |||||

| Melanocytic nevus | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | ||||

| Hemangioma | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.4) | ||||

| Localized reactive gingival lesion | 2 | 2 (0.4) | |||||

| Othersb | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 11 (1.9) | |

| Total | 110 | 47 | 280 | 98 | 5 | 30 | 570 (100) |

Percentage values calculated out of a total of 570 lesions.

Leukoplakia (1), Lichenoid drug eruption (1), Candidiasis (1), Mucosal burn (1), Denture stomatitis (1), Allergic contact stomatitis (1), Periodontal abscess (1), Papilloma (1), Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (1), Ranula (1), Herniated fat pad (1).

4. Discussion

In our study, the prevalence of oral lesions was 58.1%, which is comparable to results of studies from Slovenia (61.6%), Philippines (61.0%), and Spain (58.8%) (Cadugo et al., 1998; Kovac-Kovacic and Skaleric, 2000; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002). The prevalence of oral lesions found in Thailand (83.6%) (Jainkittivong et al., 2002) and Italy (81.3%) (Campisi and Margiotta, 2001) was substantially higher than that reported here. However, these studies were limited to populations of specific age and gender. The prevalence of oral lesions found in studies by Pentenero et al. (2008) (25.1%) and Mehrotra et al. (2010) (8.4%), which excluded harmless oral conditions and included significant oral lesions only, was found to be much lower than that of our study. Table 4 provides a summary of studies assessing the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in various populations.

Table 4.

Prevalence of oral lesions in previous studies.

| Study (Country) | Study design | Sample size | Prevalence (%) | Common lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadugo et al. (1998) (Phillipines) | Preliminary screening | 41 | 61.0% | Betel nut chewer’s mucosa (44%), geographic tongue (16%), Fordyce’s spots (8%), melanin pigmentation (8%), fibroepithelial polyp (8%), leukoedema (6%). |

| Kovac-Kovacic and Skaleric (2000) (Slovenia) | Interview and clinical examination of 25–75 year old | 555 | 61.6% | Fordyce’s condition (49.7%), fissured tongue (21.1%), varices (16.2%), history of herpes labialis (16.0%), history of recurrent aphthae (9.7%) |

| MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo (2002) (Spain) | Epidemiological study on patients for perio and prostho treatment and not for oral mucosal disorders | 337 | 58.8% | Fordyce’s disease (50.4%), melanin pigmentation (24.6%), frictional keratosis (11.5%), linea alba (10.7%), cheek biting (6.8%), traumatic ulcer (4.7%). |

| Campisi and Margiotta (2001) (Italy) | Randomly selected male population (⩾40 years) | 118 | 81.3% | Coated tongue (51.4%), leukoplakia (13.8%), traumatic lesions (9.2%), actinic cheilitis (4.6%), squamous cell carcinoma (0.9%). |

| Jainkittivong et al. (2002) (Thailand) | Clinical examination of elderly dental patients (⩾60 years) | 500 | 83.6% | Varices (59.6%), fissured tongue (28%), traumatic ulcer (15.6%) |

| Pentenero et al., 2008 (Italy) | Retrospective study. Excluded harmless oral conditions | 4098 | 25.1% | Traumatic ulcers (2.98%), cheek/lip biting (2.24%), denture stomatitis (1.9%), fibrous hyperplasia (1.78%). |

| Mehrotra et al. (2010) (India) | Screening study. Significant oral lesions only | 3030 | 8.4% | Leukoplakia (40.7%), oral submucous fibrosis (9.7%), dysplasia (7.8%), smoker’s melanosis (4.17%) |

| Mathew et al. (2008) (India) | Screening study | 1190 | 41.2% | Fordyce’s condition (6.55%), frictional keratosis (5.79%), fissured tongue (5.71%), leukoedema (3.78%), smoker’s palate (2.77%), recurrent aphthae (2.1%) |

| Jahanbani et al. (2009) (Iran) | Questionnaire and clinical examination of referred dental patients (developmental lesions only) | 598 | 49.3% | Fordyce granules (27.9%), fissured tongue (12.9%), leukoedema (12.5%), hairy tongue (8.9%) |

| Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari (2009) (Saudi Arabia) | Interview, clinical and biopsy study | 2552 | 15.0% | Fordyce granules (3.8%), leukoedema (3.4%), traumatic ulcer (1.9%), fissured tongue (1.4%), tori (1.4%), frictional hyperkeratosis (0.9%) |

| Mumcu et al. (2005) (Turkey) | Cross sectional study | 765 | 41.7% | Melanin pigmentation (6.9%), fissured tongue (5.2%), varices (4.1%), hairy tongue (3.8%), geographic tongue (1.0%) |

Similar to previous reports, our results showed a higher prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among older patients, which emphasizes the importance of routine examination of the oral mucosa, particularly in adults (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Jahanbani et al., 2009; Pentenero et al., 2008). We also noted a higher prevalence of oral lesions among tobacco and alcohol users. Al-Shammari et al. (2006) have shown smoking to be a common habit in Kuwait and that smokers have significantly less knowledge about the negative effects of smoking on oral health than nonsmokers. Also, most of them reported that they would consider quitting the habit if a link between smoking and oral health is proven to them. Our data, along with the prevailing attitudes of Kuwaiti smokers, create an exceptional opportunity for dentists to educate patients about the link between smoking and potentially harmful oral lesions and to provide tobacco-cessation counseling.

Classifying oral soft tissue lesions according to their clinical appearance is an important step in the diagnostic sequence. The dental practitioner should have information about the type and severity of lesions that tend to occur in a particular population to aid in the differential diagnosis. In this study of a Kuwaiti population, white lesions were the most common, which is consistent with studies from Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Mexico (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Castellanos and Díaz-Guzmán, 2008; Jahanbani et al., 2009; Mathew et al., 2008). It is clear that all the lesions are benign but few have malignant transformation potential such as tobacco pouch keratosis, lichen planus and leukoplakia. This emphasizes the importance of employing conservative measures such as habit cessation, periodic reevaluation and long-term follow-up.

Almost half the lesions (49.1%) in the present study were found on the buccal mucosa. Most of these lesions were related to mechanical friction or trauma which is common in this area as well as the lateral border of the tongue. Several other mucosal sites were also involved, therefore a thorough, systematic approach to the intraoral examination is important. Also, patients may have more than one lesion, so the step-by-step clinical exam should not stop once a lesion is encountered.

Fordyce granules were the most common type of oral lesion identified in this study and were more frequently found on the buccal mucosa, a finding consistent with several other studies (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Jahanbani et al., 2009; Kovac-Kovacic and Skaleric, 2000; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Mathew et al., 2008). Fordyce granules were also found more frequently among males and in the older age groups. This might be due to the high number of androgen receptors in the oral sebaceous glands (Whitaker et al., 1997). Androgens bind to these receptors, resulting in an increase in the size and metabolic rate of the sebaceous gland. Therefore, the activity and size of the glands vary according to age and circulating androgen levels. Patients with this condition can be reassured that they have no serious implications.

The second most common lesion in this study was linea alba, a white line on the buccal mucosa frequently associated with pressure, friction, or sucking trauma from the teeth (Neville et al., 2009). Linea alba was also a common finding in previous studies (Cebeci et al., 2009; Parlak et al., 2006), and was more common in older patients and in those with parafunctional habits (Khan et al., 1998).

After linea alba, the next most common lesion was generalized melanin pigmentation. Several other studies have also shown it to be one of the most common lesions (Cadugo et al., 1998; García-Pola Vallejo et al., 2002; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Mumcu et al., 2005). We observed it mostly on the gingiva, followed by the buccal mucosa, a finding similar to previous studies (Kauzman et al., 2004; Meleti et al., 2008). It occurred more frequently in this study among older patients and smokers, a finding consistent with several other studies (García-Pola Vallejo et al., 2002; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Mumcu et al., 2005; Pentenero et al., 2008). Hedin et al. (1993) have shown that increased melanin production in smokers may have a protective effect against the harmful substances in tobacco smoke.

Hairy tongue was the fourth most common lesion and also the most common tongue lesion followed by fissured tongue and geographic tongue. Similar to most previous studies, our study also found it to be more frequent in males and in tobacco users (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Campisi and Margiotta, 2001; Jahanbani et al., 2009; Jainkittivong et al., 2002; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Mumcu et al., 2005). In addition to tobacco use, hairy tongue has also been associated with poor oral hygiene and the use of specific antibiotics (Reamy et al., 2010). The dental practitioners should identify and eliminate the predisposing factors, advise regular brushing of the tongue and maintain proper oral hygiene. They should also be well- informed about the guidelines for the appropriate use of antibiotics in clinical dental practice.

Leukoedema was found to be more frequent in men and tobacco users as in previous studies (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Cadugo et al., 1998; Jahanbani et al., 2009; Mathew et al., 2008). It has been suggested that the cellular edema presenting in this condition results from chronic, mild irritation of the oral mucosa related to habits such as smoking (Versteeg et al., 2008).

After leukoedema, frictional keratosis was the next most common lesion in the study. As in other studies, it was found to be more frequent in males and smokers (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Castellanos and Díaz-Guzmán, 2008; García-Pola Vallejo et al., 2002; Mathew et al., 2008; Pentenero et al., 2008). It also occurred more often on the gingiva/alveolar mucosa. Natarajan and Woo (2008) have shown that it tends to occur on the alveolar ridge as a result of trauma from food being crushed on the gingiva/alveolar mucosa by unopposed teeth.

Similar to previous reports, fibroma was the most common exophytic lesion in this study (Byakodi et al., 2011; Castellanos and Díaz-Guzmán, 2008; Pentenero et al., 2008). The major cause of irritation fibromas is mechanical irritation from denture trauma, lip biting, calculus deposits, sharp margins of teeth and fillings, and long-term habits such as cheek biting and tongue thrusting. They can occur anywhere, but as in our study, the tongue, buccal mucosa, and lip are the most frequent sites (Barnes, 2001).

Traumatic ulcers were the most common ulcerative lesions, followed by recurrent herpes and aphthous ulcers. No malignant lesions were found in the present study, which confirms the rarity of these lesions in the oral cavity (Al-Mobeeriek and Al-Dosari, 2009; Cebeci et al., 2009; Kovac-Kovacic and Skaleric, 2000; MartínezDíaz-Canel and García-Pola Vallejo, 2002; Pentenero et al., 2008). Even though it is rare, the dental practitioner should remain alert for any suspicious lesion. Non-traumatic white patches, white patches with red areas, chronic non-healing ulcers, indurated lesions are some of the features which would make a lesion suspicious and should be investigated further. Opportunistic screening of high risk individuals will go a long way in detecting oral cancer and precancer at a relatively early stage. For the dentists to fully contribute to improvement of early detection, they must perform thorough examinations. Repeatedly training oneself to scrutinize the entire oral mucosa in a systematic fashion reduces the chance of missing any lesion.

5. Conclusion

The results of the present study provide important information about the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among patients seeking dental care in Kuwait. The information presented in this study adds to our understanding of the common oral mucosal lesions occurring in the general population. White, pigmented, and exophytic lesions were the most common types of oral mucosal lesions found. Although most of these lesions are innocuous, the dentist should nevertheless be able to recognize and differentiate them from worrisome lesions, and decide on the appropriate line of treatment. Periodic continuing education programs covering oral lesions will enhance the diagnostic ability of dental practitioners. Most lesions were more common in adults ⩾21 years and were frequently associated with tobacco use. Efforts to increase patient awareness of the oral effects of tobacco use and to eliminate the habit are needed to improve oral and general health. The results of this study should serve as the basis for a larger, nation-wide survey of oral lesions.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest associated with the study and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Ali M., Sundaram D. Biopsied oral soft tissue lesions in Kuwait: a six-year retrospective analysis. Med. Princ. Pract. 2012;21:569–575. doi: 10.1159/000339121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mobeeriek A., Al-Dosari A.M. Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental patients. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009;29:365–368. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.55166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari K.F., Moussa M.A., Al-Ansari J.M., Al-Duwairy Y.S., Honkala E.J. Dental patient awareness of smoking effects on oral health: comparison of smokers and non-smokers. J. Dent. 2006;34:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. second ed. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2001. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. [Google Scholar]

- Byakodi R., Shipurkar A., Byakodi S., Marathe K. Prevalence of oral soft tissue lesions in Sangli. India J. Community Health. 2011;36:756–759. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadugo M.A., Chua M.G., Feliciano M.A., Jimenez F.C., Jr., Uy H.G. A preliminary clinical study on the oral lesions among the Dumagats. J. Philipp. Dent. Assoc. 1998;50:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi G., Margiotta V. Oral mucosal lesions and risk habits among men in an Italian study population. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2001;30:22–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho Mde V., Iglesias D.P., do Nascimento G.J., Sobral A.P. Epidemiological study of 534 biopsies of oral mucosal lesions in elderly Brazilian patients. Gerodontology. 2011;28:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos J.L., Díaz-Guzmán L. Lesions of the oral mucosa: an epidemiological study of 23785 Mexican patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008;105:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebeci A.R., Gülşahi A., Kamburoglu K., Orhan B.K., Oztaş B. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions in an adult Turkish population. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2009;14:E272–E277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin C.D., Jones A.V. A survey of oral and maxillofacial pathology specimens submitted by general dental practitioners over a 30-year period. Br. Dent. J. 2006;200:447–450. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pola Vallejo M.J., Martínez Díaz-Canel A.I., García Martín J.M., González García M. Risk factors for oral soft tissue lesions in an adult Spanish population. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:277–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin C.A., Pindborg J.J., Axéll T. Disappearance of smoker’s melanosis after reducing smoking. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1993;22:228–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanbani J., Sandvik L., Lyberg T., Ahlfors E. Evaluation of oral mucosal lesions in 598 referred Iranian patients. Open Dent. J. 2009;3:42–47. doi: 10.2174/1874210600903010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jainkittivong A., Aneksuk V., Langlais R.P. Oral mucosal conditions in elderly dental patients. Oral Dis. 2002;8:218–223. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.01789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauzman A., Pavone M., Blanas N., Bradley G. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: review, differential diagnosis, and case presentations. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2004;70:682–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F., Young W.G., Daley T.J. Dental erosion and bruxism. A tooth wear analysis from south east Queensland. Aust. Dent. J. 1998;43:117–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb06100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovac-Kovacic M., Skaleric U. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a population in Ljubljana. Slovenia J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2000;29:331–335. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais R.P., Miller C.S., Nield-Gehrig J.S. fourth ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Illinois: 2009. Color Atlas of Common Oral Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- MartínezDíaz-Canel A.I., García-Pola Vallejo M.J. Epidemiological study of oral mucosa pathology in patients of the Oviedo School of Stomatology. Med. Oral. 2002;7:4–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew A.L., Pai K.M., Sholapurkar A.A., Vengal M. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in Southern India. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2008;19:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra R., Thomas S., Nair P., Pandya S., Singh M., Nigam N.S., Shukla P. Prevalence of oral soft tissue lesions in Vidisha. BMC Res. Notes. 2010;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleti M., Vescovi P., Mooi W.J., van der Waal I. Pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa and perioral tissues: a flow-chart for the diagnosis and some recommendations for the management. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008;105:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumcu G., Cimilli H., Sur H., Hayran O., Atalay T. Prevalence and distribution of oral lesions: a cross-sectional study in Turkey. Oral Dis. 2005;11:81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan E., Woo S.B. Benign alveolar ridge keratosis (oral lichen simplex chronicus): a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville B.W., Damm D.D., Allen C.M., Bouquot J.E. third ed. Saunders Elsevier; Missouri: 2009. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. [Google Scholar]

- Parlak A.H., Koybasi S., Yavuz T., Yesildal N., Anul H., Aydogan I., Cetinkaya R., Kavak A. Prevalence of oral lesions in 13- to 16-year-old students in Duzce. Turkey Oral Dis. 2006;12:553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentenero M., Broccoletti R., Carbone M., Conrotto D., Gandolfo S. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in adults from the Turin area. Oral Dis. 2008;14:356–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reamy B.V., Derby R., Bunt C.W. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am. Fam. Physician. 2010;81:627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg P.A., Slot D.E., van der Velden U., van der Weijden G.A. Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2008;6:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker S.B., Vigneswaran N., Singh B.B. Androgen receptor status of the oral sebaceous glands. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1997;19:415–418. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199708000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]