Abstract

Children living in households affected by HIV face numerous challenges as they take on significant household-sustaining and caregiving roles, often in conditions of poverty. To respond to their hardships, we must identify and understand the support systems they are already part of. For this reason, and to emphasise the agentic capabilities of children, this article explores how vulnerable children cope with hardship through peer social capital. The study draws on the perspectives of 48 HIV-affected and caregiving children who through PhotoVoice and draw-and-write exercises produced 184 photographs and 56 drawings, each accompanied with a written reflection. The themes emerging from the essays reveal that schools provide children with a useful platform to establish and draw on a mix of friendship structures. The children were found to strategically establish formalised friendship groups that have the explicit purpose of members supporting each other during times of hardship. The children also formed more natural friendship groups based on mutual attraction, with the implicit expectation that they will help each other out during times of hardship. In practice, the study found that children help each other through sharing (e.g. schools material and food) as well as through practical support (e.g. with domestic duties, securing food, and income-generation) — thus demonstrating that children are able to both accumulate and benefit from ‘peer social capital.’ The study concludes that a key coping strategy of HIV-affected and caregiving children is to mobilise and participate in friendship groups which are characterised by sharing and reciprocity of support. Development responses to support children affected by the HIV epidemic need to take heed of children's ability to draw on peer social capital.

Keywords: community support, HIV/AIDS, participatory action research, PhotoVoice, social networks, sub-Saharan Africa, visual methods

Introduction

As parents fall ill from HIV, children may find themselves taking on significant household-sustaining and caregiving roles, often in contexts of poverty, which may compromise their education and psychosocial wellbeing (Skovdal & Ogutu, 2009). This is a cause for concern, encouraging both local and international organisations to develop strategies and responses that promote the wellbeing and growth of children affected by HIV. While service delivery organisations can play an important role in facilitating supportive and health-enabling environments for children affected by HIV, such efforts must resonate with children's agency and consider innate support systems. It is against this background, and in the interest of highlighting the opportunities for social participation that schools can provide for HIV-affected and caregiving children, that this article explores the nature of children's peer relations, looking explicitly at how they are formed and the ways they can be drawn upon by vulnerable children to successfully deal with hardship.

Extensive research from the ‘global North’ has highlighted the importance of peer groups in promoting reciprocity, collaboration and acceptance (Hartrup, 1983; Parker & Asher, 1993) and made great efforts to map out the organisation and dimensions of peer relations (see Brown, 2004; Gest, Graham-Bermann & Hartup, 2001), yet little research has explicitly focused on the importance of friendship for HIV-affected children in sub-Saharan Africa. The wider HIV/AIDS-related literature however does allude to the importance of friendships in a number of different ways. First, studies have expressed, albeit briefly and in passing, that friendships may be an invaluable source of support for HIV-affected children (Murray, 2010) and that peer connections might serve as a protective factor in helping HIV-affected children build resilience (Cluver, Bowes & Gardner, 2010; Wild, Flisher & Robertson, 2011).

Second, studies exploring children's experiences of HIV and AIDS have highlighted that children express concern that they might lose their friends. This has been demonstrated for example in studies that report on children moving in with extended family members to help them cope with the impact of HIV and AIDS, leaving their friendship groups behind (Evans, 2005; Skovdal, 2011a). In Lesotho and Malawi, one study found that children who migrate to stay with extended family following the deaths of their parents mentioned missing their friends and feeling isolated before new friendship groups had been established, forming part of the negative aspects of moving (Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006). But it is not migration alone that forces children to leave their friendship groups. Children who stay in their local community but drop out of school in order to cope with significant care and household-sustaining responsibilities (as their parents fall ill or die) have also been found to feel isolated after losing their friends (Skovdal & Ogutu, 2009; Yanagisawa, Poudel & Jimba, 2010). A study of orphaned children heading households in Uganda found children with extensive care and home duties struggling to nurture their friendships, primarily because they had to drop out of school and were busy generating income for their household (Dalen, Nakitende & Musisi, 2009). These studies all indicate that HIV-affected children value their friendships, but give no further background about what it is about these friendships that is so valuable.

Third, studies have found that children and youths, who may not necessarily be affected by HIV and AIDS themselves, represent and describe their HIV-affected peers as having supportive friendship groups. In Malawi, for example, young people suggested that HIV-affected youths had friends and peer groups who would provide them with advice and encouragement to adopt healthy attitudes and behaviours (Wright, Lubben & Mkandawire, 2007). Similar observations have been made in Zimbabwe where children aged 10 to 12 years spoke about the importance of friends in providing HIV-affected children with a break from their care and household-sustaining duties. The children also suggested that friends may go and help HIV-affected children with their care and household-sustaining duties (Campbell, Skovdal, Mupambireyi & Gregson, 2010). These studies have alluded to some of the more concrete ways in which friendships may help HIV-affected children, such as through encouragement and practical support during times of hardship.

Finally, an expanding body of literature argues that bringing children together and providing them with a space to share with peers and reflect upon their experiences is key to their psychosocial wellbeing (e.g. Thupayagale-Tshweneagae & Benedict, 2011). This has been attempted in different ways. In Tanzania, traditional healers have been observed to involve children and youths in traditional dances and theatre in order to integrate orphaned children into community life and give them the opportunity to form friendships (Kayombo, Mbwambo & Massila, 2005). In Kenya, a local nongovernmental organisation (NGO) mobilised youth clubs for caregiving children, providing them both with a space to meet and form friendships with children in similar circumstances as well as giving them resources to engage in income-generating activities — fostering team work while helping to address their immediate needs (Skovdal, 2010). Looking at children's experiences of going to school in Uganda, Meinert (2009) found that schools provide children with a unique opportunity to form friendship groups and develop peer cultures, which are key to their socialisation and how they experience the impact of HIV and AIDS. Schools are therefore seen as an important space for children to develop and nurture friendships, as illusterated by some of the many school-based peer-support programmes that have been set up to improve the mental health of HIV- and AIDS-affected children (e.g. Cluver, 2009; Kumakech, Cantor-Graae, Maling & Bajunirwe, 2009). In Uganda, a peer-group support programme met with orphaned children twice weekly over a 10-week period, encouraging them to participate in psychosocial exercises that encouraged sharing and reflection (Kumakech et al., 2009); the peer-group-support intervention led to improvements in reported levels of depression, anger and anxiety. The common denominator in these interventions is that they all draw on the premise that peer support and friendships play a role in helping HIV- and AIDS-affected children deal with hardship.

Although no previous study, to our knowledge, has set out to explore how children in the context of HIV draw on friendship networks to cope with hardship, there is plenty to suggest that friendship and peer support does have an impact on how HIV-affected children cope with hardship. The above review alludes to three possible networks, or forms of social capital, that can positively impact children's coping. These are: 1) the close friends of HIV- and AIDS-affected children (bonding social capital); 2) peers from the wider community (bridging social capital); and, 3) schools or other organisations facilitating peer-support (linking social capital). We now turn to use this brief review as a platform to develop a ‘peer social capital’ framework.

Towards a ‘peer social capital’ framework

The concept of social capital (see Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000) is increasingly used to understand the social psychological resources that children — at a micro-level — invest in and actively negotiate access to in dealing with life circumstances (Morrow, 1999; Barry, 2011). Coleman (1988 and 1990), combining the rationality of individuals and the social structures in which they are located, argues that children and young people actively develop friendship groups who can offer support in times of hardship. He goes on to argue that once friendship groups have been established, children and young people are ready to go to great lengths to sustain their friendships, particularly throughout adolescence and in times of domestic turmoil, where friendship networks can take on greater significance than the family (Coleman, 1990). Barry (2011), drawing on the work of Coleman and other social-capital theorists in relation to young carers in the United Kingdom, found friends to feature highly in the lives of young carers. The positive impact of having close friends was not only about having someone to talk to about their home situation, it was also about giving them the opportunity to be like other children and youths, escaping their caring role, to be free from worries (Barry, 2011).

As evidenced by the work of Barry and Coleman referred to above, theories of social capital provide a useful platform to investigate the importance of friendships for children to cope with hardship. However, social capital is by no means a straightforward concept. The theory of social capital has a significant intellectural history and has been pulled in different directions. In this article we draw on three varieties, or social psychological processes, of social capital as characterised by key theorists (cf. Putnam, 2000; Woolcock, 2001; Szreter, 2002). The first one relates to bonding social capital, where people develop supportive and close relationships with people similar to themselves, built on trust, reciprocity and a shared identity. Such relations are important for children and young people in order to ‘get by’ (Morrow, 1999). The literature reviewed above indicates that social ties and the closeness of established friendship groups are important for HIV- and AIDS-affected children, but gives no indication of the nature of these friendships and how they help children cope with hardship.

A second process of social capital relates to bridging social capital, where people interact with social networks beyond their own social group, but within a similar setting. Bridging social capital is based on the premise that no social groups are located in a vacuum, but will be influenced by other social networks. For example, children who are part of a peer group, characterised by support and trust, do not function in isolation. Peer groups interact with each other, for better or for worse. A peer group of HIV-affected children for example may be ostracised and bullied by children and youths from another peer group in the local area, which can have a negative influence on their psychological coping and ability to navigate for support (Cluver & Orkin, 2009). Morrow (1999) states that if children are to ‘get on’ (i.e. move beyond just getting by), they must gain the support of and work in partnership with other social networks.

A third category of social capital has been referred to as linking social capital. Linking social capital relates to the interaction between people and networks across social strata and institutionalised power hierarchies with the aim of accessing support and leveraging resources (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). For HIV-affected children, educational establishments and international organisations (through teachers and social workers) provide the linkages and opportunities for children to develop new peer relations (thus linking social capital).

‘Peer social capital’ may therefore relate to the opportunities and social resources that are available for HIV-affected children to develop close friendships (i.e. bonding social capital), be supported by peers from their school environment and wider community (i.e. bridging social capital) and participate in peer-support activities, facilitated by teachers, social workers or NGO staff (i.e. linking social capital). A ‘peer social capital’ framework can place greater emphasis on the role of friendship and peer-support in enabling or restricting children's coping with hardship. It also points towards some of the dynamics that need to be considered for any responses looking to facilitate children's coping through peer support and friendship.

Although this study alludes to the importance and relevance of HIV stigma in undermining friendships (negative bridging social capital) as well as the role of schools and international organisations in facilitating peer-supportive social spaces (linking social capital), the overall aim of this study is to explore how children actively organise themselves into friendship groups (generate bonding social capital) and make productive use of them to cope with hardship (utilise bonding social capital). In doing so, this study highlights their agency and latent coping strategies.

Methods

The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the London School of Economics and Political Science, as well as the Department for Gender, Children and Social Development in Kenya. Observing the ethical guidelines of the British Psychological Society (2004), informed and written consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians with the agreement that confidentiality would be ensured. We therefore use pseudonyms throughout.

Study population and sampling

The study was conducted in the Bondo district of western Kenya. The district borders Lake Victoria and is predominantly inhabited by the Luo ethnic group who primarily engage in fishing and subsistence farming. Bondo is characterised by frequent droughts and laterite soils with poor water-retention capacity, which contribute to high levels of poverty and food insecurity (Government of Kenya, 2006). This, coupled with seasonal migration to fishing villages, has encouraged local people to engage in transactional sex, contributing to the rapid spread of HIV in the district. HIV prevalence in the district is conservatively estimated at 13.7%, still twice the national average of 7.4% (National AIDS Control Council, 2006; National AIDS and STI Control Programme/Ministry of Health, 2008; UNAIDS, 2008). The district was carved out of Siaya district in May 1998, which meant that the building of a district infrastructure and administration took precedence at the peak of the HIV epidemic. This resulted in a delayed response to the epidemic. Over the past decade, the district has therefore experienced an influx of nongovernmental organisations and bilateral support to help the district and its local population respond to HIV and AIDS. However, the combination of poverty, the early onset of HIV infection or AIDS illness and a delayed response to the management of HIV has led to a surge in the number of HIV- or AIDS-affected children in the district. A survey done by Nyambedha, Wandibba & Aagaard-Hansen (2003) in Bondo district found that one out of three children (33.6% of the 724 sample size) had lost one or both parents, and one out of nine children had lost both biological parents.

This study forms part of a participatory action research project that set up with two youth clubs for 48 caregiving children (between the ages of 12 and 17) in two rural communities in western Kenya. The sociodemographic characteristics of the children, as well as whom they care for, are presented in Table 1. The children and youths met weekly or fortnightly to spend time with children of similar circumstances, either through workshops, sports or income-generating activities as part of a life-skills programme. The youth clubs were facilitated by a local NGO and provided a platform to recruit and engage with HIV-affected and caregiving children for the purpose of this study. As the material drawn upon in this study was gathered at the very start of the project, the youth clubs do not feature as a source of social capital, and the children's perspectives are likely to reflect innate ties and networks and not those generated from their participation in the youth clubs.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participating caregiving children (n = 48), Bondo district, western Kenya

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||

| Girls | 28 | 58 |

| Boys | 20 | 42 |

| Age group: | ||

| 12–14 years | 29 | 60 |

| 15–17 years | 19 | 40 |

| Orphan status: | ||

| Paternal orphan (child has lost father) | 30 | 63 |

| Double orphan (child has lost both parents) | 9 | 19 |

| Social orphan (child is vulnerable to poverty and parental illness) | 6 | 12 |

| Maternal orphan (child has lost mother) | 3 | 6 |

| Guardian (whom the child lives with): | ||

| Mother | 24 | 50 |

| Grandmother | 10 | 21 |

| Aunt | 7 | 15 |

| Sister | 3 | 6 |

| Father | 2 | 4 |

| No one | 2 | 4 |

| Care recipient (whom the child currently cares for): | ||

| Mother | 25 | 52 |

| Grandmother | 9 | 19 |

| Aunt | 7 | 15 |

| Grandfather | 3 | 6 |

| Neighbour | 2 | 4 |

| Father | 1 | 2 |

| Sister | 1 | 2 |

Data collection and analysis

In our interest to do research “with children rather than on or for children” (Matthews, Limb & Taylor, 1998, p. 312), PhotoVoice was used a research method. PhotoVoice is a participatory research methodology that enables children to share their life experiences as well as reflect and develop perspectives on life challenges by producing and reflecting on images (Wang & Burris, 1997; Wang, 2006). PhotoVoice is traditionally used to involve lay-people and encourage them to identity challenges to their health and wellbeing, with the aim of increasing the awareness of policymakers. Here, PhotoVoice is used to highlight coping strategies, arguing that such a focus will bring forward both life challenges and indicators for action and change that are aligned with local resources (Skovdal, 2011b).

Through a series of workshops — facilitated by local NGO staff in the local Dholuo language — the children were sensitised to the PhotoVoice project. They were informed that the purpose of the exercise was to explore their coping strategies and they were taught how to use the disposable cameras. We also discussed some of the ethical implications of using PhotoVoice (for examples, see: Gold, 1989; Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001; Skovdal & Abebe, 2012). Through these discussions it was agreed by the children to not take undignified photos of parents or guardians who may be ill and bedridden. It was also agreed that if photos were to be taken inside their homes, these photos should be staged or acted (as opposed to a snapshot of ‘reality’). If children wanted to take photos of people, they were asked to first seek permission and consent to do so. In the workshops, the children practiced what they had to say in order to obtain informed consent. If the children wanted to share a story, but for ethical reasons or time constraints were unable to take the photo, they were encouraged to draw the scene and write a story about that.

The children had the disposable cameras for two weeks and were provided with four guiding questions: 1) What is good about your life? 2) Who helps you? 3) What keeps you strong? and 4) What needs to change? All 48 cameras were returned, but one camera turned out to be faulty and the child was given a new camera and a chance to repeat the exercise. After all the photographs had been developed, the children were gathered in a workshop setting and encouraged to select up to six photographs that would tell a story about how they get by, things they lack, and/or something or someone who is important to them. The children were then invited to reflect on their photographs and write down their reflections. To prompt the children, they were given three questions: 1) ‘I want to share this photo because…’; 2) ‘What is the real story this photo tells?’; and 3) ‘How does this story relate your life and/or the lives of people in your neighbourhood?’

This exercise generated a total of 184 photographs and 56 drawings, each accompanied with a written reflection. We draw on these written stories in this artcle. However, to exemplify the kind of photos the children produced, we have included a couple of the pictures in our presentation of findings (see Figures 1 and 2). The stories were translated from Dholuo into English and imported into Atlas. Ti — a qualitative data analysis software package. Following the steps of Attride-Stirling's (2001) thematic network analysis, text segments were coded with an interpretive title and subsequently clustered into basic themes. As we do not seek to report on all of the themes emerging from this analysis, the coding framework was revisited, this time guided by the literature presented in thisarticle in order to explore how the codes making reference to friendship were interconnected. Through this process, 13 basic themes were identified, each of which were clustered into three organising themes, covering: 1) how the school environment provides children with opportunities to form close friendship groups; 2) how the children coped through sharing; and 3) how the children coped by helping each other more practically at home.

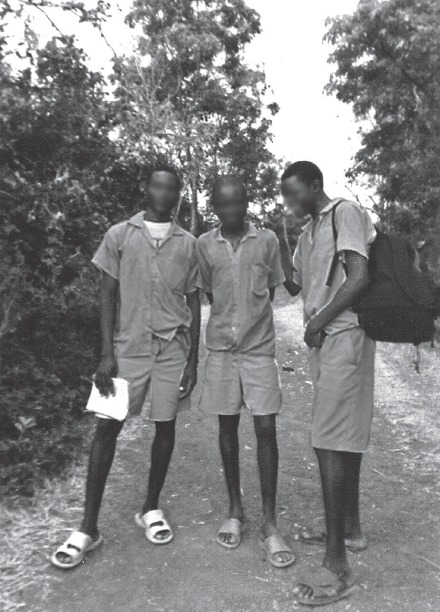

Figure 1:

Picture taken by Fanuel (age 17) showing his three best friends

Figure 2:

Picture taken by Lucy (age 12) showing her schoolmates

As we seek to map out the stock of resources and perspectives articulated by our informants in an exploratory manner, it is not our aim to draw links between individual children's accounts and their personal backgrounds (e.g. social and orphan status, number of friendship groups). However, we try to distinguish between majority and minority views, by clarifying whether the perspectives were held by many of the children or only some. Next, we discuss the primary themes emerging from this study with the aim of answering the research question: How do HIV-affected and caregiving children cope with hardship through friendship?

Findings

The combination of poverty and HIV can have catastrophic consequences for how children experience their schooling and peer relations. As parents fall ill from HIV or other related illnesses and require around-the-clock care and support, it is often the children of the household who step in. For example, one boy described his escalating experiences of caring for his mother, which eventually resulted in him having to drop out of school temporarily:

‘I drew a picture of my mother to share with you the kind of caring I did for her. I was caring a lot for my mother; I was washing her, bathing her, washing her feet, cooking for and feeding her. I had to ensure that she was asleep before I did. I only slept for a little while and woke up early to clean the house, washed her and fed her before going to school. But I had to drop school at some point; it was really bad for me. I left school at one time to be with her all the time and that wasn't good for me at all’ (Mark, age 13).

Not only do children like Mark drop out of school temporarily to provide care, some are denied the opportunity to go to school in the first place because the associated costs are unattainable for many families. Some children have the assets necessary to generate income that will allow them to attend school. In one of her written stories, 15-year-old Mildren explained how she grew and sold crops so that she could afford to go to school. However, rather than telling us that the school was providing her with invaluable life skills and knowledge, which is one of the primary aims of educational establishments, Mildren, when explaining the importance of going to school, placed her emphasis on how the school has helped her develop friendships:

‘At home we grow a variety of crops and we benefit a lot from the farm. We harvest and sell the crops to get money which we use to pay for school. This has helped me to socialise and meet many friends’ (Mildren, age 15).

Despite the fact that many of the caregiving children had experienced stigmatisation and bullying from peer groups at their school, many of our informants, like Mark, were deeply unhappy about having to drop out of school. Having noted this, there were occasions where children, like Everline, expressed bullying as a reason why some children did not want to go to school:

‘Sometimes I did not go to school because groups of children there who have never cared just talk bad about your name. They joke about the condition of your parent’ (Everline, age 14).

The experiences of our informants, as illustrated by Mark, Mildren and Everline (above), confirm what has been previously described in the literature. First, that HIV stigma may result in the bullying of HIV-affected children by other peers (a type of negative bridging social capital). Second, that HIV-affected children on the whole value going to school (a form of linking social capital), socialising with peers, and developing friendships (bonding social capital). But how are these friendship groups organised?

Children generate bonding social capital through mobilising friendship groups

Schools provide children with a space to identify and develop friendship groups based on mutual understanding, respect and support, loyalty, trust and fun. These friendship groups appear to be organised through a mix of formalised and informal friendship structures which transcend the school environment where they are formed.

Formalised friendship groups

A number of children spoke about being part of groups that were formed by children themselves on the mutual understanding that the group members would help each other during times of hardship. Often the groups were formed at school and with school friends, having the primary purpose of making sure that everyone in the group was able to attend school and do well in class. As 12-year-old Kevin highlighted, this more formal approach to mobilising friendship groups is rooted in their observations of the achievements of adult community-based groups in their local communities. Kevin and his peers knew that through team and collaborative work they were more likely to succeed at school:

‘It is good if we are in a group while being taught in school as there is an understanding amongst us and we can learn better. In our exams we do better than others from various areas and schools. I took this photo because of the good relationship we have amongst us, we cooperate. Team work helps. Being in a group has helped women in a village where they were weeding as a group, harvesting, and this ensured that their crops did well and they got a good harvest’ (Kevin, age 12).

But the support groups often extend beyond school-based encouragement and work. As 15-year-old Millicent highlighted, being part of a support group made a huge difference to her. She explained how her fellow group members, because of their shared love and respect, were able to assist her and her mother through a difficult time, providing them with both practical and emotional support through home visits:

‘I want to talk about this photo because these school children have formed a group, which I am a part of. We help each other. I once had a problem and they helped me through a difficult time. They regularly came to visit my mother and they also helped me fetching water and firewood. This photo shows us that we should love and visit each other, because if we respect one another we can assist one another. If I have problems, my fellow children help me. This picture shows that while some have plenty of things, a friend may have less and we can always join hands, so small fundraising to help someone through a situation’ (Millicent, age 15).

Thus Millicent recommended that friends ‘join hands’ in these more formal structures, since such structures can help someone through times of hardship.

Informal friendship groups

In addition to, or instead of, these more formalised friendship groups, children also form smaller and more naturally occurring friendship groups that ascend out of mutual attraction, with parity governing their social exchanges. Seventeen-year-old Fanuel took a photo of his three best friends (Figure 1) and described how important they were to him, both in helping him generate income, but also through encouragement and advice:

‘This picture shows three school children. These children come from the village where I live and go to the same school as me. I took a photo of them because they are happy and because I love them. They are important to me because they help me live well. The boy carrying a schoolbag on the photo is a close friend of mine; I love him very much because he takes the time to teach me many things and helps me with my studies. If he sees me playing and have left studies, he reminds me to go back to the books and says — Son of Alego, you came here to learn, learn, and this will help you in the future. Some friends when they see me playing, they just join me and encourage play. The other two boys I also love, because if they find me working they will join me and help me, even if it is hard work. They do help me and encourage me by saying that there is nowhere in the world where work is easy, saying that I should be prepared to work. And whenever I hear these wise words from them, I become happy and that is why I took a photo of them’ (Fanuel, age 17).

Fanuel loved his friends and appreciated the fact that they wanted what is best for him and helped him stay focused on living well and responsibly. Similarly, 15-year-old Janet expressed affection for a small group of close friends. For Janet, friends enabled her to escape her caregiving role temporarily. She was appreciative of the fun she could have with her friends as well as the opportunities to confide in them:

‘The people on this photo usually come around to my place. We play together, we chat, we play as a group, and have fun. The photo reminds me of how at times I can become very happy with my friends and the stories we share’ (Janet, age 15).

While the children greatly valued the benefits of more formal friendship structures, it is clear from both Fanuel and Janet that smaller and more naturally occurring friendship groups based on mutual attraction offered a level of intimacy and shared happiness that larger and more formalised friendship structures, based on mutual commitment to support each other during times of hardship, do not provide. Although we have presented these two types of friendship structures separately, the children are not part of either structure in isolation, but rather draw on both structures interchangeably as a way of optimising their bonding social capital. Having established the organisation of supportive peer relations, we now outline how friendship groups practically utilise this bonding social capital to cope with hardship.

Friends share what they have

One way friends help each other is through sharing. As 12-year-old Lucy suggested, friendship starts with sharing:

‘I want to talk about this photo [Figure 2] because they are my schoolmates. The one with the red jumper is my neighbour. It shows my classmates and children from other classes. I took the photo of them because of our good relationships and it reminds me of how we help one another and can share most things amongst each other’ (Lucy, age 12).

One way to sustain your participation in a friendship group is therefore to share and help out during times of hardship. Although the sharing of joys, pains, feelings and fun is fundamental to all friendships and relationships, in this particular context of poverty and disease, sharing more material items becomes symbolic of the quality of a friendship.

Friends share school materials

The school environment is the primary space for children to share and establish friendships. A number of children spoke about how friends helped them obtain school materials in times of need. Both Clare and Millicent explained that if they lacked anything in school, their school-attending friends would share their own items with them:

‘I want to talk about this photo because on it is my schoolmate and friend. She is also my neighbour. The photo reminds me of our good relationship; if I lack a pencil, I can share with her, the same goes for books’ (Clare, age 12).

‘I wish to talk about this photo as it shows my friends. My friends are good, they help me in school because at times I may lack a pen and if I go to anyone of them and ask them, they always give me one’ (Millicent, age 15).

Friends share food

The children also spoke about the importance of sharing food, helping them to overcome food insecurity and to diversify their diet. Fifteen-year-old Carren, in highlighting the importance of friends in helping caregiving children cope with hardship, told how she could go and ask her friends for vegetables to cook if she was short of food:

‘The photo shows how important friends are to one's life. These friends of mine can help me in various ways. Some of them cultivate vegetables, and if I don't have food, I can go to them and ask them if they can help me. They will give me some vegetables to go and cook’ (Carren, age 15).

These subsections have highlighted sharing as a key strategy for HIV-affected and caregiving children to access the food and items they otherwise lack, illustrating that sharing is an integral part of friendship in this particular context.

Friends help each other in practical ways

Another way friends help each other cope with hardship is through practical support. They do this by assisting with household chores and caring duties as well as securing food and income-generation.

Friends assist with domestic responsibilities

As parents or guardians fall ill and children take on more and more responsibilities, it becomes increasingly difficult for the children to balance all their domestic and caring responsibilities with their social life and schooling. One way to overcome this challenge was to carry out these duties and responsibilities with a friend, making it a social activity:

‘I took this picture of my friend whom I always go with whenever we need to fetch something, like fetching water and firewood. We always go to the places together’ (William, age 14).

However, for some children the household chores and caring duties escalate and become so difficult that their friends decide to step in and help out. This was illustrated by Janet who stated that children in the community related well to each other, highlighting a sense of solidarity and understanding for the hardship that some children endure. As such, Janet's friends occasionally helped her fetch water, releasing her for some of her duties as a caregiver:

‘In our area, where we live, my fellow school children sometimes come to me, we play together, some love me very much and sometimes bring me water. The photo shows us how fellow children and others help me and bring for me water. We children relate well to one another in the community. At times they assist me and that is why I took this photo, to remind me of that’ (Janet, age 15).

But friends were not only found to help out with fetching firewood and water. Fifteen-year-old Paddy described how his friends, during times when his mother was ill, had assisted him with cooking, cleaning and washing clothes:

‘These children are my friends and they also help me when my mother is sick. They assist me with washing clothes, cooking, cleaning and fetching of water’ (Paddy, age 15).

Friends assist with food and income-generation

As parents or guardians fell ill, many children assumed responsibility for their home allotment (shamba) and livestock, which are key livelihood assets. In addition to helping out with domestic duties and the caregiving of a friend's parent, the children supported each other in providing for and sustaining their households. Fifteen-year-old Pascal for example took a photo of a friend who helped him during periods of hardship and parental illness, explaining that this friend not only assisted him with caring for his mother, but also helped look after their goats:

‘This photo shows my friend who assists me at times when my mother is sick. He comes to help me doing certain duties, such as washing clothes, utensils, tethering the goats and cleaning the homestead’ (Pascal, age 15).

Sixteen-year-old Zeddy also took a photo of one of his friends to show how important his friends were in helping him cope with his life's challenges. Zeddy struggled in school and spent many hours completing household duties. Assisting him was his friend, who despite coming from another community, would make the journey to come and help Zeddy with homework and working on the farm:

‘This is my friend and he assists me in school, even at home, despite the fact he lives in Lale, far away from us. He helps me with weeding, clearning the compound and in the farm. I also help him in ways he wants’ (Zeddy, age 16).

Zeddy importantly highlights the reciprocity involved in nurturing and accessing these supportive friendships. Zeddy pointed out that the help he received was not charity, but an outcome of his support of his friend. Not all caregiving children however are able to keep the sharing and support reciprocal, and this can have a devastating impact on their friendships. Seventeen-year-old Felicity explained how one of her friends, who had previously helped her out, got tired of supporting Felicity and broke all ties with her:

‘There was a certain child called Mercy in our village, that was coming to help me. We also spent the night together with her and another child; all the three of us slept together; she helped me until she became tired of me. After she had left I was just alone with some community health workers from our community’ (Felicity, age 17).

Felicity's example of losing a friend demonstrates that friendships must be nurtured through sharing and reciprocity. Children's friendship groups are not necessarily stable and children may break from the group and move on to another friendship group if they feel they give more than they get in return. Nevertheless, these sub-sections have illustrated the importance of friends in helping HIV-affected and caregiving children cope with home duties as well as with securing food and income-generating activities.

Discussion

The research aimed to explore the role of friendships in helping HIV-affected and caregiving children cope with hardship, and in so doing, to highlight children's agency as well as the opportunities for social participation and friendship formation that the school environment offers. To situate this study within the wider literature on the role of friendship networks and peer-support for HIV-affected children, we located the study within a ‘peer social capital’ framework. This framework argues that programme planners and policy actors need to consider the enabling or inhibiting roles of three types of social networks. These networks are: 1) children's close friendships (bonding social capital); 2) peers from the wider community and school environment (bridging social capital); and, 3) opportunities to participate in peer-support activities facilitated by teachers, social workers and NGO staff (linking social capital). Although the findings allude to the inhibiting role of peers in the wider community, who could be observed to bully the caregiving children, and point towards the importance of schools in facilitating peer-support programmes, the study has focused on children's close friendships. More specifically, we set out to explore how children who are affected by HIV and with significant careigiving roles, actively organise themselves into friendship groups (generate bonding social capital) and make productive use of these friendship groups to cope with hardship (utilise bonding social capital).

The findings highlight a tremendous sense of empathy and mutual understanding among certain children in this community, arguably because of their shared experience of being impacted by poverty and disease. Children in this context were fully aware that by working together and supporting each other, they are more likely to cope with hardship. To achieve this, the children organised and established a mix of friendship structures that were either formed strategically with the explicit purpose of the children supporting each other during times of hardship (we have called these formalised friendship groups), or they formed friendships naturally based on mutual attraction, with the implicit expectation that they would help each other out during times of hardship (we have called these informal friendship groups). Both types of friendship groups constitute bonding social capital. In practice, the children helped each other cope with hardship in different ways. The children gave examples of how friends shared both school materials (e.g. books and pens) and food (e.g. vegetables or other crops grown by their friends) and helped each other practically with domestic duties (e.g. cleaning, washing, fetching water and firewood) as well as with securing food and income-generation (e.g. animal keeping and farming). These findings clearly demonstrate that HIV-affected and caregiving children are able to both accumulate and benefit from peer social capital.

Aside from illustrating how the agentic capabilities of children in this context help HIV-affected and caregiving children draw on peer social capital to cope with hardship, the findings also point towards some of the contextual factors that enable children to draw on their friendship networks during times of hardship. The school environment is clearly conducive for the development of close friendships and meeting like-minded peers who can lend a hand and share what they have during times of hardship. Although schools are often perceived as simply spaces of learning, we suggest that the school environment is a key space for the development of peer social capital. This being noted, schools are also a conducive environment for the generation of HIV stigma and the bullying of children affected by HIV (cf. Cluver et al., 2010).

Another contextual factor relates to the local understandings and expectations of friendship. Friendships in this poverty-stricken context appeared characterised by sharing and mutual support. While it can be argued that sharing between friends is a natural trait of friendship and may not pertain to their needs as caregiving and HIV-affected children, sharing in this context appeared to be integral to how the children evaluated the quality of a friendship. A final contextual factor contributing to these coping-enabling friendships relates to the children's observations and imitation of how adult members of community groups support each other by working together as a team and formally commit to reciprocity and sharing. Nyambedha & Aagaard-Hansen (2007) looked into the emergence of community groups in Bondo district and they argue that although duol and siwindhi, which are concepts signifying unity and solidarity within a lineage under the authority of elders, are no longer practiced in the traditional sense, new structures (e.g. church and community groups — thanks to church and donor assistance) dominate the way communities provide care and support for people affected by HIV or AIDS, including children. Unlike the traditional system, the current system transcends kinship patterns and other traditional and gendered relations in Luo social life — responding to contemporary challenges, including HIV and AIDS (Nyambedha & Aagaard-Hansen, 2007). It appears that children in this context will draw on this new structure and way of providing community support as they negotiate support from their friends.

These two contextual factors appear to have arisen from local responses to poverty and the HIV epidemic. This suggests that although the interaction between poverty and HIV is devastating for entire communities, children in these communities are able to adopt new practices (e.g. mobilise support from formalised support networks and their close friendship groups) and build on existing norms (e.g. friendship is characterised by material sharing and reciprocity) that help them cope. One might even suggest that the HIV epidemic has provided children and communities with new opportunities for social participation and social change.

A limitation of using PhotoVoice in this study is that it did not involve a formal dialogue, in the form of an interview, between the children and the researcher. Although the children wrote about reciprocity, perhaps indicating that the children within their friendship groups were both vulnerable and in need of support, we cannot comment on whether the children formed the friendship groups based on their individual life experiences and identities. Webb (2007) noted a tendency of orphaned children to form friendship groups as a result of stigma and discrimination, however; he warns that this may contribute to a social stratification of society.

The exploratory nature of the study leaves questions unanswered, but opens up opportunities for further investigation. Does the size of the friendship groups matter? Do children with many friends cope better? How do children who have just moved into a new area and joined a new school access these supportive peer groups? Is it a shared identity that nurtures these friendships?

Despite many unanswered questions, we conclude that ‘peer social capital,’ understood as the norms and practices that children draw on and adopt to secure benefits through membership in formalised and/or informal friendship groups, plays a key role in enabling HIV-affected and caregiving children cope with difficult circumstances. This coping strategy illustrates children's agency in responding to hardship and must be considered by programme planners and policy actors, together with an appreciation of the contextual factors that enable children to mobilise and participate in friendship networks.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children who participated in this study. We also thank Cellestine Aoro for her help with facilitating the PhotoVoice project.

The authors

Morten Skovdal (PhD) is a community health psychologist writing about children's health and community responses to HIV. He is with the Department of Health Promotion and Development at the University of Bergen and a Visiting Research Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Vincent Onyango Ogutu is a community development professional and the managing director of WVP Kenya, a nongovernmental organisation supporting children and youths made vulnerable by poverty and disease.

References

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1(3):385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Barry M. ‘I realised that I wasn't alone’: The views and experiences of young carers from a social capital perspective. Journal of Youth Studies. 2011;14(5):523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson J.G., editor. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society. Guidelines for Minimum Standards of Ethical Approval in Psychological Research. Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In: Lerner R., Steinberg L., editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C., Skovdal M., Mupambireyi Z., Gregson S. Exploring children's stigmatisation of AIDS-affected children in Zimbabwe through drawings and stories. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(5):975–985. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L. Peer-group-support intervention reduces psychological distress in AIDS orphans. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2009;12(4):120. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.12.4.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L., Bowes L., Gardner F. Risk and protective factors for bullying victimization among AIDS-affected and vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34(10):793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L., Orkin M. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(8):1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(supplement):S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.S. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dalen N., Nakitende A.J., Musisi S. ‘They don't care what happens to us’: The situation of double orphans heading households in Rakai District, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009. p. 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans R. Social networks, migration, and care in Tanzania: caregivers’ and children's resilience to coping with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Children and Poverty. 2005;11(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gest S.D., Graham-Bermann S.A., Hartup W.W. Peer experience: common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Social Development. 2001;10(1):23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gold S. Ethical issues in visual fieldwork. In: Blank G., McCartney J., Brent E., editors. New Technology in Sociology: Practical Applications in Research and Work. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kenya. Bondo District Annual Monitoring and Evaluation Report. Vol. 2005. Government of Kenya, Ministry of Planning and National Development [Accessed from Bondo District Resource Centre]; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hartrup W. The peer system. In: Hetherington E., editor. Handbook of Child Psychology. Volume 4: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kayombo E.J., Mbwambo Z.H., Massila M. Role of traditional healers in psychosocial support in caring for the orphans: a case study of Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2005. p. 1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumakech E., Cantor-Graae E., Maling S., Bajunirwe F. Peer-group support intervention improves the psychosocial wellbeing of AIDS orphans: cluster randomized trial. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H., Limb M., Taylor M. The geography of children: some ethical and methodological considerations for project and dissertation work. Journal of Geography in Higher Education. 1998;22(3):311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert L. Hopes in Friction: Schooling, Health and Everyday Life in Uganda. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow V. Conceptualising social capital in relation to the wellbeing of children and young people: a critical review. The Sociological Review. 1999;47(4):744–765. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J.S. Collaborative community-based care for South African children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2010;15(1):88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Council (NACC) [Kenya] Kenya HIV/AIDS Data Booklet. Vol. 2006. Nairobi, Republic of Kenya: NACC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS and STI Control Programme/Ministry of Health (NASCOP/MOH) [Kenya] Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS) 2007 Preliminary Report. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP/MOH; 2008. Available at: < http://www.nacc.or.ke/2007/images/downloads/kais__preliminary_report_july_29.pdf> [Accessed 24 August 2009] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E., Aagaard-Hansen J. Practices of relatedness and the re-invention of duol as a network of care for orphans and widows in western Kenya. Africa. 2007;77(4):517–534. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E., Wandibba S., Aagaard-Hansen J. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(2):301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J., Asher S. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(4):611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M. Community relations and child-led microfinance: a case study of caregiving children in western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22(supplement 2):S1652–S1661. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M. Examining the trajectories of children providing care for adults in rural Kenya: implications for service delivery. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011a;33(7):1262–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M. Picturing the coping strategies of caregiving children in western Kenya: from images to action. American Journal of Public Health. 2011b;101(3):452–453. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M., Abebe T. Reflexivity and dialogue: methodological and socio-ethical dilemmas in research with HIV-affected children in East Africa. Ethics, Policy and Environment. 2012;15(1):77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M., Ogutu V. ‘I washed and fed my mother before going to school’: Understanding the psychosocial wellbeing of children providing chronic care for adults affected by HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. Globalisation and Health. 2009;5(8) doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szreter S. The state of social capital: bringing back in power, politics and history. Theory and Society. 2002;31(4):573–621. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter S., Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;33(4):650–667. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G., Benedict S. The burden of secrecy among South African adolescents orphaned by HIV and AIDS. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2011;32(6):355–358. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.576128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV and AIDS: Kenya. Vol. 2008. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Blerk L., Ansell N. Children's experiences of migration: moving in the wake of AIDS in southern Africa. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 2006;24:449–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Youth participation in PhotoVoice as a strategy for community change. In: Checkoway B., Gutiérrez L.M., editors. Youth Participation and Community Change. Binghamton, New York: Haworth Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Burris M. PhotoVoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behaviour. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Redwood-Jones Y. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from Flint Photovoice. Health Education and Behaviour. 2001;28(5):560–572. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb D. Interventions to support children affected by HIV/AIDS: priority areas for future research. In: Foster G., Levine C., Williamson J., editors. A Generation At Risk: The Global Impact of HIV/AIDS on Orphans and Vulnerable Children. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wild L.G., Flisher A.J., Robertson B.A. Risk and resilience in orphaned adolescents living in a community affected by AIDS. Youth and Society. 2011. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11409256.

- Woolcock M. Microenterprise and social capital: a framework for theory, research and policy. Journal of Socio-Economics. 2001;30:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wright J., Lubben F., Mkandawire M.B. Young Malawians on the interaction between mental health and HIV/AIDS. African Journal of AIDS Research (AJAR) 2007;6(3):297–304. doi: 10.2989/16085900709490425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa S., Poudel K.C., Jimba M. Sibling caregiving among children orphaned by AIDS: synthesis of recent studies for policy implications. Health Policy. 2010;98(2/3):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]