Summary

Haptoglobin (Hp), a major acute-phase plasma protein, has been found in arthritic synovial fluid (SF). However, the function and structural modifications of Hp in arthritic SF are unknown. To investigate in vivo generation of modified Hp associated with inflammatory disease, we examined a new Hp isoform in SF from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Specific Hp fragments of 28 000 and 15 000 molecular weight were identified in SF of patients with RA, and the two polypeptides were presumed to be fragments of the Hp β-chain (43 000 MW) produced by cleavage with plasmin. The 15 000 MW fragment, which is a C-terminal region of Hp, was observed at higher frequency and levels in RA than in osteoarthritis. Plasmin activity was also higher in SF of RA patients. A recombinant 15 000 MW Hp fragment up-regulated interlukin-6 expression in monocytic cells. These findings indicate that the C-terminal Hp fragment is generated by plasmin in local inflammatory environments and acts as an inflammatory mediator. They further suggest that a specific Hp fragment might be applied as a novel biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of inflammatory diseases such as RA.

Keywords: biomarker, haptoglobin, plasmin, rheumatoid arthritis, synovial fluid

Introduction

Haptoglobin (Hp) is a major acute-phase glycoprotein and its concentration in the circulation increases twofold to fourfold during conditions of inflammation, injury and malignancy.1,2 Haptoglobin plays a critical role in tissue protection against haemoglobin-induced oxidative damage,4–5 and acts as an angiogenic factor for arterial restructuring and vascular repair.6,7 The protein participates in induction of haem oxygenase-1 and interleukin-10 in activated monocytes and macrophages.9 The inhibitory function of Hp in endotoxin-induced inflammation was also reported both in vitro and in vivo.10 Based on these findings, Hp has been considered an anti-inflammatory regulator and a tissue protector. However, Shen et al.11 showed recently that Hp stimulates the production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α via a MyD88-dependent pathway in CD11c+ dendritic cells and activates innate immunity in a mouse model of skin transplantation, which resulted in acute transplant rejection. These findings suggest a pro-inflammatory function of Hp. Although Hp is primarily synthesized in the liver, extrahepatic Hp expression has been also found in adipose tissue, lung and artery.12,13 Specifically, immune cells such as monocytes and neutrophils are known to participate in Hp synthesis and secretion.15,16 Therefore, it seems likely that Hp acts systemically or locally as either an anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory mediator depending on the cellular environment. However, it is not known whether native Hp acts conflictingly depending on the circumstances or whether Hp that is modified in specific environments exerts different activities.

In humans there are two major Hp alleles, Hp1 and Hp2, which result in three major Hp polymorphisms, Hp 1-1 (Hp1/Hp1), Hp 2-1 (Hp1/Hp2), and Hp 2-2 (Hp2/Hp2). These Hp isoforms manifest as functional differences in anti-oxidant and angiogenic activities; the Hp 2-2 phenotype is a weak anti-oxidant and a significantly higher risk factor for microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with diabetes mellitus.1 In addition, Hp proteins with different glycosylation states have been found. In particular, fucosylated Hp was identified in plasma from cancer patients and has been suggested as a useful biomarker for the diagnosis of pancreatic and colon cancers.18–19 These findings suggest that Hp may exist in various forms and exert diverse activities in vivo.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that results in the destruction of articular cartilage and bone. During the onset of the disease, RA synovial tissues express numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that participate in inflammatory cell recruitment, synovial hyperplasia, autoantibody production, cartilage matrix damage and bone erosion.20 Haptoglobin has been found in arthritic synovial fluid (SF) and its local expression in inflamed joints was reported.21–22 However, the function and structural modifications of Hp in arthritic SF are unclear. We hypothesized that a specifically modified Hp is formed in inflammatory environments such as RA and is involved in the induction of inflammation. To investigate whether modified Hp associated with inflammatory disease is generated in vivo, we examined a new Hp isoform in SF from patients with RA.

Materials and methods

Preparation of SF samples

Samples of SF were obtained from 20 patients with RA and 16 patients with osteoarthritis (OA), and diluted with one volume PBS. After removal of cells and debris by centrifugation at 500 g for 10 min, the supernatants were stored at −80° until use. The study methodologies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea.

Purification and identification of the Hp fragment from the SF of RA patients

Samples of SF from RA patients were pooled and applied to a CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B gel (Sigma, St Louis, MO) coupled with anti-Hp antibody (Sigma). After washing with coupling buffer (0·1 m NaHCO3 containing 0·5 m NaCl, pH 8·3), bound proteins were eluted with 0·1 m glycine–HCl (pH 2·6). The eluted fractions were immediately neutralized by the addition of 1/10 volume of 1 m Tris–HCl buffer (pH 9·5) and concentrated 10-fold using a Centricon ultrafiltration apparatus with a 3000 molecular weight (MW) cut-off (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

The concentrated protein sample was electrophoresed on a 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R (Sigma). After washing with distilled water overnight, a protein band of 28 000 MW was cut from the gel and analysed by mass spectrometry with a Thermo Finnigan LCQ DeCa Xp Max mass spectrometer (C18 cartridge column) at the Korea Basic Science Institute (Seoul, Korea).

Digestion of Hp by plasmin

Purified human Hp (15 μg; Sigma) and plasmin (0·50 μg; Sigma) were mixed in 50 μl Tris–HCl buffer (0·05 m, pH 8·2) and incubated at 37° for 5 hr. Digested Hp was analysed by Western blot. In an experiment of Hp digestion by urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) system, the conditioned culture medium of MDA-MB 231 breast cancer cells was used as a source of uPA; MDA-MB231 cells were cultured to 80% confluence in RPMI-1640 medium (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco Life Technology, Gaithersburg, MD). After medium was replaced by serum-free RPMI-1640, the cells were cultured for a further 24 hr. The conditioned culture medium was collected and uPA in the medium was identified by Western blot using uPA antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). For Hp digestion in the cellular system, MDA-MB231 cells (5 × 105) were seeded in a 12-well plate. After the cells were attached, medium was changed to the conditioned medium (uPA source), and 2 μg/ml purified Hp 1-1 or 2-2 and 5 μg/ml of human plasminogen (Sigma) were added to the medium. The cells were incubated for 0·5–5 hr and C-terminal Hp fragment (C-term Hp) that had accumulated in the medium was detected by Western blot.

Determination of plasmin activity

Plasmin activity was measured using a SensoLyte AFC (7-amido-4-trifluormethylcoumarin) plasmin activity assay kit (AnaSpec, Inc., San Jose, CA), which is based on the quantification of AFC fluorophore released from a fluorogenic substrate upon plasmin activity. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western blot analysis of SF samples

Twelve microlitres of each SF sample was electrophoresed on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. The separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. For analysis, rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human Hp (Sigma), human Hp α, and C-term Hp were used as primary antibodies. The antibodies to Hp α and C-term Hp were prepared in our laboratory by immunizing rabbits with recombinant proteins. The immunoreactive proteins were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) using the luminescent image analysis system-3000 (Fuji film, Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of recombinant C-term Hp

DNA corresponding to C-term Hp was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, 5′-GCC ATA TGT TTA CTG ACC ATC TGA AGT ATG TC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCC TCG AGG TTC TCA GCT ATG GTC TTC TGA AC-3′ (reverse), and subcloned into NdeI and XhoI sites of pET22b+ vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The sequence of the cloned DNA was confirmed by a commercial service (Cosmo Genetech, Seoul, Korea).

The C-term Hp was expressed as a histidine-tagged fusion protein in DE3 cells (Escherichia coli strain BL21) and purified using Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) under denaturing conditions of 8 m urea according to the manufacturer's directions. The eluted protein was allowed to refold by gradual removal of the urea, which was performed by successive changes of dialysis solution into decreasing concentrations of urea. Finally, the protein sample was dialysed into PBS solution without urea. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contamination in the preparations was examined by chromogenic Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate-Kinetic QCL™ assay kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), and the endotoxin level was < 3 EU/μg protein (< 0·3 ng LPS/μg C-term Hp).

Cell culture and treatment

The THP-1 human monocytic cell line was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. To examine the effect of C-term Hp on IL-6 expression, cells were plated in a 24-well culture plate at a density of 3 × 105/well and treated with 10 μg/ml C-term Hp (LPS < 3 ng/ml) or LPS (1–10 ng/ml; Sigma) for 24 hr. For the inhibition assay, the cells were pre-incubated with 3 μm CLI-095 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) or 0·5 μm auranofin (Alexis, Lausen, Switzerland) for 1 hr before C-term Hp treatment.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan) in an MX-3000P thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Complementary DNA was amplified using the following specific primers: IL-6, 5′-GAA CTC TTC TCC ACA AGC GCC TT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAA AAG ACC AGT GAT GAT TTT CAC CAG G-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′ (reverse).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Protein concentrations of IL-6 were determined using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the unpaired Student's t-test to assess differences between the results. Data were analysed using graphpad prism (version 5·04) software (GraphPad software, Inc., San Diego, CA). A P-value < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of a specific Hp fragment in SF from patients with RA

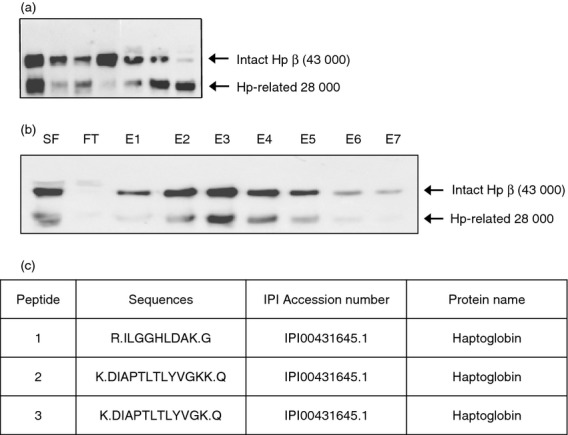

To identify an inflammation-related Hp isoform, SF from RA patients was analysed by Western blot with anti-Hp antibody. An unusual 28 000 MW band was observed in SF from RA patients (Fig. 1a). This Hp-related 28 000 MW band was present at a higher frequency in SF from RA patients than in patients with OA (data not shown). To isolate the 28 000 MW protein, we carried out affinity chromatography using pooled SF from patients with RA. Both the 28 000 MW protein and native Hp were detected in the fractions eluted from the affinity gel coupled with anti-Hp antibody (Fig. 1b). After electrophoretic separation of the eluted proteins on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel, the 28 000 MW band was excised from the gel and analysed by LC-Q mass spectrometry. Three peptides from the 28 000 MW protein matched the N-terminal region of the Hp β-chain (amino acids 1–9 and 55–67; Figs 1c and 2c). These findings indicate that the 28 000 MW polypeptide in SF of RA patients is a fragment of the Hp β-chain.

Figure 1.

Detection of haptoglobin (Hp)-related 28 000 molecular weight (MW) protein in synovial fluid (SF) from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and identification as a fragment of the Hp β-chain. (a) Equal volumes of SF samples were electrophoresed on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions. The separated proteins were analysed by Western blot using anti-human Hp antibody. In addition to the Hp β-chain of 43 000 MW, an unusual 28 000 MW band was also detected. (b) SF samples from RA patients were pooled, and affinity chromatography was performed using a CNBr-Sepharose gel coupled with antibody against human Hp. The intact Hp β-chain and the 28 000 MW protein were detected in the eluted fractions. Fractions E2–E5 were pooled and concentrated. SF, pooled SF sample; FT, flow through; E, eluted fraction. (c) After electrophoretic separation of the concentrated sample, the area corresponding to 28 000 MW was cut from the gel and LC-Q/mass spectrometry was performed. The results were analysed using sequest (version 3·31) software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA), and three peptides from the 28 000 MW protein matched the N-terminal region of the Hp β-chain (amino acids 1–9 and 55–67).

Figure 2.

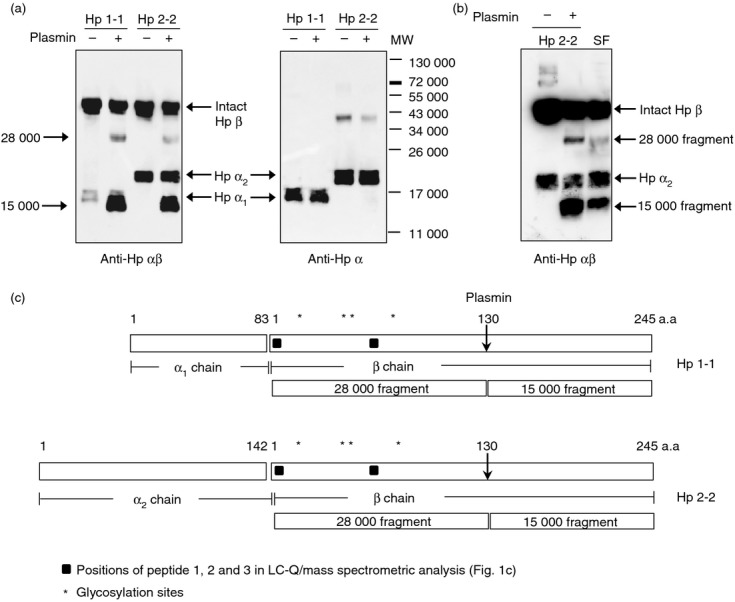

Production of 28 000 and 15 000 molecular weight (MW) fragments from the haptoglobin (Hp) β-chain by plasmin digestion. (a) Hp (15 μg) purified from human plasma was incubated with plasmin (0·5 μg) at 37° for 5 hr. The digested mixture was analysed by Western blot with antibodies against Hp (left) and Hp α-chain (right). Note that the antibody to the Hp α-chain does not detect plasmin-produced Hp fragments (28 000 and 15 000 MW). (b) Western blot comparing synovial fluid (SF) from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and undigested or plasmin-digested Hp 2-2 in the same gel. (c) Schematic of the structures of human Hp 1-1 and Hp 2-2. A cleavage site for plasmin and the resultant fragments of 28 000 and 15 000 MW are shown.

Cleavage of Hp β-chain by plasmin and production of 28 000 and 15 000 MW fragments

Synovial fluid of RA patients contains several proteases. Because Hp contains a cleavage site for plasmin,23 we investigated Hp fragmentation by plasmin. Incubation of purified human Hp 1-1 and Hp 2-2 with plasmin at 37° for 5 hr produced 28 000 MW and 15 000 MW polypeptides, with decreased amounts of the Hp β-chain (Fig. 2a, left). The Hp α-chain remained unchanged after the incubation. In the Western blot using antibody against Hp α-chain, Hp 2-2 showed another band of 40 000 MW besides the α2-chain (Fig. 2a, right). This was thought to be a dimer of Hp α2, because the same size band was detected in the preparation of recombinant Hp α2 (data not shown). Western blot results of plasmin-digested Hp 2-2 were identical to those of the SF sample from an RA patient with the Hp 2-2 phenotype (Fig. 2b) indicating that the Hp-related 28 000 MW polypeptide in SF may be a plasmin-cleaved Hp fragment. To identify the cleavage site, a reaction mixture of Hp 2-2 and plasmin was separated on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. A 15 000 MW band was cut from the gel, and N-terminal amino acid sequencing was performed. The results indicate that plasmin cleaved the Hp β-chain at Lys-130 (data not shown), which is consistent with results previously reported by Kurosky et al.23 Therefore, the 28 000 and 15 000 MW polypeptides correspond to the N-terminal and C-terminal fragments of the Hp β-chain, respectively (Fig. 2c).

Differential distribution of C-terminal Hp fragment in SF from RA and OA patients

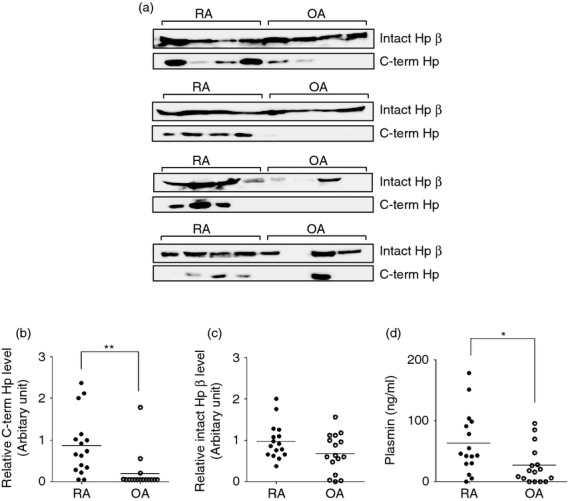

The 28 000 MW fragment from the Hp β-chain gradually degraded during storage whereas the C-terminal 15 000 MW fragment (C-term Hp) remained stable. Therefore, we decided to measure C-term Hp instead of the 28 000 MW fragment to verify the presence of plasmin-modified Hp in body fluids of patients. Because the size of C-term Hp is similar to that of the Hp α1-chain, the bands corresponding to C-term Hp and Hp α1 overlapped in Western blot analysis using anti-Hp antibody (Fig. 2a). To detect only C-term Hp, we prepared an antibody against recombinant C-term Hp and used it in Western blot analysis. Using this antibody, C-term Hp could be detected in most SF samples from RA patients (14/16 samples) but was observed at lower frequency (3/16 samples) in OA samples (Fig. 3a). Levels of C-term Hp were also significantly higher in SF samples from RA patients than in those from OA patients (P < 0·01; Fig. 3b). When the intact Hp β-chain was examined, we observed relatively higher levels in RA patients than in OA patients, although these results were not significant (Fig. 3c). However, C-term Hp levels were not directly proportional to native Hp levels in SF samples, indicating that the formation of C-term Hp in RA patients was not a result of higher levels of native Hp.

Figure 3.

Comparison of C-terminal haptoglobin (C-term Hp) levels in synovial fluid (SF) samples from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or osteoarthritis (OA). (a) SF samples from RA (n = 16) and OA (n = 16) patients (12 μl) were electrophoresed on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and the separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was cut into two parts: one contained the intact Hp β-chain (43 000 molecular weight) and the other contained C-term Hp (15 000 molecular weight). To detect the intact β-chain and C-term Hp, rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human Hp (Sigma) and C-term Hp (our laboratory), respectively were used as the primary antibodies. The immunoreactive proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit and luminescent image analysis system. The exposure times for the detection of intact β-chain and C-term Hp were 30 seconds in standard sensitivity and 60 seconds in high sensitivity, respectively. (b, c) The intensity of each band for C-term Hp (b) and Hp β-chain (c) was measured and expressed as an arbitrary relative value. The horizontal line shows the mean value. **P < 0·01 versus OA group. (d) Plasmin concentrations in SF from RA and OA patients were measured using a SensoLyte AFC plasmin activity assay kit. The horizontal line shows the mean value. *P < 0·05 versus OA group.

Because plasmin is required for C-term Hp generation, its enzymatic activity in SF was determined. As shown in Fig. 3(d), RA samples contained significantly higher levels of plasmin than OA samples (P < 0·05). It therefore appears that C-term Hp can be produced in inflammatory environments with sufficient Hp and plasmin.

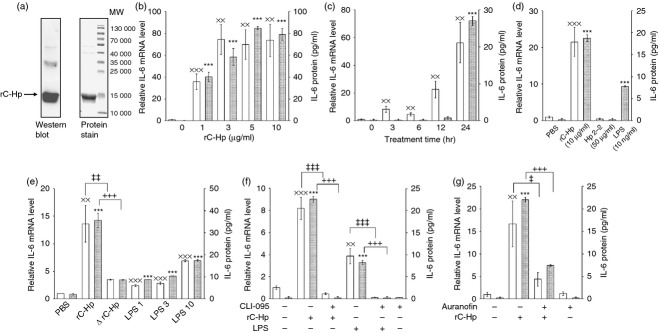

Up-regulation of IL-6 expression by C-term Hp in THP-1 monocytic cells

Inflammatory IL-6 is a pivotal cytokine in the pathogenesis of RA.20 To examine the effect of C-term Hp on IL-6 expression, we prepared recombinant C-term Hp (Fig. 4a). At a concentration of 1–10 μg/ml, C-term Hp increased the levels of IL-6 mRNA and protein in THP-1 monocytic cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4b,c). Unlike C-term Hp, native Hp did not show the IL-6-enhancing activity at 50 μg/ml, a concentration that corresponds to 10 μg/ml C-term Hp in terms of molar concentration (C-term Hp, 15 000 MW; (α-β) monomer of Hp 2-2, 63 000 MW) (Fig. 4d). Although the effect of LPS in C-term Hp preparation was not excluded, 10 μg/ml C-term Hp (< 3 ng LPS) was more potent than 3 ng/ml LPS with respect to IL-6 induction (Fig. 4e). The induction was significantly abrogated when heat-inactivated C-term Hp was used (Fig. 4e). Therefore, it seems that the IL-6 induction, partly at least, is an effect of C-term Hp. Unfortunately, an experiment using the LPS inhibitor Polymyxin B could not be carried out because C-term Hp was precipitated in the presence of Polymyxin B for an uncertain reason. When cells were pre-incubated with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) inhibitor CLI-095 before the treatment of C-term Hp, the IL-6 induction was completely blocked indicating that TLR4 signalling is involved in the functional mechanism of C-term Hp (Fig. 4f). In addition, the anti-rheumatic drug auranofin markedly inhibited the induction of IL-6 expression by C-term Hp (Fig. 4g). These results suggest that C-term Hp may play a role as a pro-inflammatory mediator via TLR4 signalling in arthritic environments.

Figure 4.

Induction of interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression by recombinant C-terminal haptoglobin (C-term Hp). (a) Recombinant C-term Hp (rC-Hp) was prepared as described in the Materials and methods. To check purity, the polypeptide was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (right) and analysed by Western blot using anti-Hp antibody (left) after electrophoretic separation on a 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. (b–g) The effect of rC-Hp on IL-6 expression was examined in THP-1 cells. (b) Cells were treated with rC-Hp (1–10 μg/ml) for 24 hr. (c) Cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml rC-Hp for the indicated times (3–24 hr). (d) rC-Hp (10 μg/ml), Hp 2-2 (50 μg/ml), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 ng/ml) were added to the cells for 24 hr. (e) Cells were incubated for 24 hr in media containing 10 μg/ml rC-Hp (LPS < 3 ng/ml) without or with heat-inactivation at 95° for 15 min (ΔrC-Hp). LPS1, LPS3 and LPS10 mean the treatment with LPS of 1 ng/ml, 3 ng/ml and 10 ng/ml, respectively. (f) After pre-incubation for 1 hr without or with Toll-like receptor (TLR4) inhibitor CLI-095 (3 μm), cells were treated with rC-Hp (10 μg/ml) or LPS (10 ng/ml). (g) Cells were pre-incubated for 1 hr without or with the anti-rheumatic drug auranofin (0·5 μm) before treatment with 10 μg/ml rC-Hp for 24 hr. After the incubation, relative levels of IL-6 mRNA in the treated cells were measured by reverse transcription–quantitative PCR and normalized to the corresponding GAPDH level. IL-6 protein concentrations were determined by ELISA using the corresponding cell culture media. The results are shown as means ± SD of data from triplicate assays. rC-Hp was prepared twice independently and the experiments were performed at least twice using each preparation. The results were similar between experiments and representative results are shown here. The mRNA levels and protein concentrations are revealed as white bars and grey bars, respectively. xxP < 0·01, xxxP < 0·001 versus vehicle-treated control group for mRNA level. ***P < 0·001 versus vehicle-treated control group for protein level. ‡P < 0·05, ‡‡P < 0·01, ‡‡‡P < 0·001 versus rC-Hp or LPS-treated group (mRNA). +++P < 0·001 versus rC-Hp or LPS-treated group (protein).

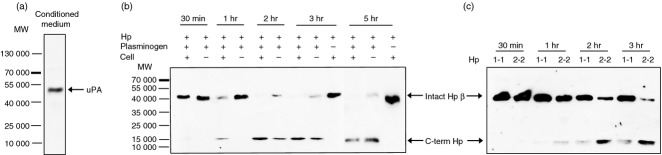

Generation of C-term Hp by uPA/uPAR/plasminogen system

The serine protease uPA activates plasminogen into plasmin, and the activation is amplified by its receptor uPAR on the cell surface. We examined whether C-term Hp could be generated by uPA/uPAR in the cellular system. As a uPA source, we used the conditioned medium of MDA-MB 231 human breast cancer cells to be cultured for 24 hr (Fig. 5a), because the cells constitutively express uPA and uPAR at high levels.24 When purified Hp 2-2 was incubated with plasminogen in the conditioned medium, Hp β-chain was degraded and C-term Hp was generated. The C-term Hp production was greater in the presence of cells possessing uPAR, but the cleavage did not occur without plasminogen (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that C-term Hp can be yielded in vivo by activated plasmin in the local inflammatory sites with abundant uPA and uPAR, although uPA/uPAR does not act directly on the Hp cleavage. To investigate whether uPA/uPAR-mediated C-term Hp generation is dependent on Hp polymorphism, Hp 1-1 and Hp 2-2 were incubated with plasminogen in the culture system of MDA-MB 231 cells. The result indicates that Hp 2-2 is a better substrate than Hp 1-1 with respect to C-term Hp generation (Fig. 5c), which suggests that individuals with the Hp2 gene may be associated more strongly with inflammatory diseases.

Figure 5.

Generation of C-terminal haptoglobin (C-term Hp) by plasmin activated by uPA/uPAR in cellular system. The conditioned culture medium of MDA-MB231 cells were collected as described in the Materials and methods. (a) uPA in the conditioned medium was identified by Western blot. (b) Hp 2-2 (2 μg/ml) and human plasminogen (5 μg/ml) were added to the conditioned culture medium in the presence or absence of MDA-MB231 cells. After incubation for 0·5–5 hr, the medium (30 μl) was analysed by Western blot using antibody against C-term Hp. Note that C-term Hp can be produced earlier in the presence of cells (uPAR source) but is not generated without plasminogen. (c) Hp 1-1 or Hp 2-2 was incubated with the cells in the conditioned medium containing plasminogen and analysed by Western blot. Note that more C-term Hp is generated from Hp 2-2.

Discussion

We identified, for the first time, a specific C-terminal Hp fragment of 15 000 MW in SF from patients with arthritis that appears to be produced by the action of activated plasmin. Although in vitro Hp cleavage by plasmin was previously reported,23 the disease-related existence of the resultant fragment in vivo had not been shown. C-term Hp was present at a higher frequency and levels in the SF of RA patients than in SF of OA patients. In addition, the polypeptide induced IL-6 expression in monocytes. These findings suggest that C-term Hp is generated specifically in the arthritic environment and may participate in the pathogenesis of RA by inducing inflammatory mediators.

Active plasmin has been found in arthritic SF and it is essential for the induction of inflammatory joint destruction in early phases of RA.25 Increased uPA in inflamed SF also contributes to RA induction.26 Moreover, Hp can be locally expressed in joints of inflammatory arthritis and is detectable in SF from RA patients.21–22 These findings support our results showing that C-term Hp can be generated by uPA/uPAR-mediated plasmin activity in inflamed arthritic SF. C-term Hp generation in the cellular system with uPA/uPAR was dependent on Hp phenotype and Hp 2-2 was a better source than Hp 1-1. Haptoglobin 2-2 shows polymer forms of (αβ)n (n ≥ 3) while Hp 1-1 is a heterotetramer of (αβ)n (n = 2). Therefore, it is likely that Hp 2-2 may be a better source of C-term Hp that is a plasmin-cleaved β-chain fragment. However, we do not know yet whether Hp polymorphism is associated with RA induction. To answer the question, further study is required.

Haptoglobin has shown contrary effects in inflammation, acting as an anti-inflammatory or a pro-inflammatory regulator.9,10 In the present study, C-term Hp induced IL-6 expression in monocytic cells, whereas native Hp did not show the activity of IL-6 induction at an equimolar concentration. This suggests that structural modifications or differences must be considered in terms of Hp action.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease accompanied by chronic inflammation. The disease affects approximately 1% of the population worldwide, and increases morbidity and mortality.20 While IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α are considered pivotal inducers of RA, the molecular mechanism involved in its pathology remains unidentified. To diagnose early RA, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are commonly measured; however, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are not specific for RA.27 As their combined use with other RA-associated factors is predicted to improve RA diagnosis in terms of specificity and sensitivity, several candidate proteins in SF and plasma from RA patients have been studied.28–29

Significantly elevated Hp levels in serum from RA patients compared with those from healthy individuals have suggested that Hp could serve as a biomarker of RA.30 However, individual differences in Hp expression have been shown, dependent on genetic polymorphism: individuals with the Hp 2-2 phenotype have relatively low levels of Hp in the circulation compared with those with the Hp 1-1 phenotype. Concentration of Hp in normal plasma varies from 0·3 to 3 mg/ml.1 If the generation of disease-specific Hp isoforms is considered together with increased Hp levels, the diagnosis of RA will be improved. In the present study, the RA-related, plasmin-mediated C-term Hp fragment was found in SF from patients with arthritis. Together, these findings suggest that plasmin-generated C-term Hp may be used as a novel biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of inflammatory diseases such as RA. A comparative study between C-term Hp and specific clinical data is required to verify this application. In the following study, we will investigate the function of C-term Hp and its relationship to RA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Wan-Uk Kim (Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea) for samples from RA and OA patients. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Programme through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0009165).

Glossary

- AFC

7-amido-4-trifluormethylcoumarin

- C-term Hp

C-terminal region haptoglobin

- Hp

haptoglobin

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MW

molecular weight

- OA

osteoarthritis

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SF

synovial fluid

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- uPA

urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- uPAR

urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Levy AP, Asleh R, Blum S, et al. Haptoglobin: basic and clinical aspects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:293–304. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MK, Park HJ, Kim NH, Park SJ, Park IY, Kim IS. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α enhances haptoglobin gene expression by improving binding of STAT3 to the promoter. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8857–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YK, Jenner A, Ali AB, et al. Haptoglobin reduces renal oxidative DNA and tissue damage during phenylhydrazine-induced hemolysis. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1033–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SK, Moestrup SK. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid MC, Grant DS, Hoffman GS, Auerbach R, Fauci AS, Kleinman HK. Identification of haptoglobin as an angiogenic factor in sera from patients with systemic vasculitis. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:977–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI116319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleijn DP, Smeets MB, Kemmeren PP, et al. Acute-phase protein haptoglobin is a cell migration factor involved in arterial restructuring. FASEB J. 2002;16:1123–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0019fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Baek SH, Oh MK, et al. Enhancement of angiogenic and vasculogenic potential of endothelial progenitor cells by haptoglobin. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippidis P, Mason JC, Evans BJ, Nadra I, Taylor KM, Haskard DO, Landis RC. Hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 mediates interleukin-10 release and heme oxygenase-1 synthesis: antiinflammatory monocyte–macrophage responses in vitro, in resolving skin blisters in vivo, and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Circ Res. 2004;94:119–26. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109414.78907.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredouani MS, Kasran A, Vanoirbeek JA, Berger FG, Baumann H, Ceuppens JL. Haptoglobin dampens endotoxin-induced inflammatory effects both in vitro and in vivo. Immunology. 2005;114:263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Song Y, Colangelo CM, et al. Haptoglobin activates innate immunity to enhance acute transplant rejection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:383–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI58344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiellini C, Santini F, Marsili A, et al. Serum haptoglobin: a novel marker of adiposity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2678–83. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Ghio AJ, Herbert DC, Weaker FJ, Walter CA, Coalson JJ. Pulmonary expression of the human haptoglobin gene. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:277–82. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets MB, Pasterkamp G, Lim SK, Velema E, van Middelaar B, de Kleijn DP. Nitric oxide synthesis is involved in arterial haptoglobin expression after sustained flow changes. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:221–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IS, Lee IH, Lee JH, Lee SY. Induction of haptoglobin by all-trans retinoic acid in THP-1 human monocytic cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:738–42. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theilgaard-Monch K, Jacobsen LC, Nielsen MJ, et al. Haptoglobin is synthesized during granulocyte differentiation, stored in specific granules, and released by neutrophils in response to activation. Blood. 2006;108:353–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkova N, Gilbert C, Goupil S, Yan J, Korobko V, Naccache PH. TNF-induced haptoglobin release from human neutrophils: pivotal role of the TNF p55 receptor. J Immunol. 1999;162:6226–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi E, Nakano M. Fucosylated haptoglobin is a novel marker for pancreatic cancer: detailed analyses of oligosaccharide structures. Proteomics. 2008;8:3257–62. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Lee SH, Kawasaki N, et al. α1-3/4 fucosylation at Asn 241 of beta-haptoglobin is a novel marker for colon cancer: a combinatorial approach for development of glycan biomarkers. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2366–76. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes IB, Schett G. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:429–42. doi: 10.1038/nri2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinz A, Bantscheff M, Mikkat S, et al. Mass spectrometric proteome analyses of synovial fluids and plasmas from patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and comparison to reactive arthritis or osteoarthritis. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:3445–56. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200210)23:19<3445::AID-ELPS3445>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz ME, Wilson DC, Marinov AD, et al. Synovial fluid proteins differentiate between the subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1813–23. doi: 10.1002/art.27447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosky A, Barnett DR, Lee TH, et al. Covalent structure of human haptoglobin: a serine protease homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3388–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanivong C, Yu J, Huang S. Elevated urokinase-specific surface receptor expression is maintained through its interaction with urokinase plasminogen activator. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:165–75. doi: 10.1002/mc.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ny A, Leonardsson G, Nandakumar KS, Holmdahl R, Ny T. The plasminogen activator/plasmin system is essential for development of the joint inflammatory phase of collagen type II-induced arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:783–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxne T, Lecander I, Geborek P. Plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitors in synovial fluid. Difference between inflammatory joint disorders and osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekara S, Sachin S. Measures in rheumatoid arthritis: are we measuring too many parameters. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal MA, Woodworth T, Henriksen K, et al. Biochemical markers of ongoing joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis–current and future applications, limitations and opportunities. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:215. doi: 10.1186/ar3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lu J, Bao J, Guo J, Shi J, Wang Y. Adiponectin: a biomarker for rheumatoid arthritis? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cylwik B, Chrostek L, Gindzienska-Sieskiewicz E, Sierakowski S, Szmitkowski M. Relationship between serum acute-phase proteins and high disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Med Sci. 2010;55:80–5. doi: 10.2478/v10039-010-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]