Abstract

Background: tools are required to identify high-risk older people in acute emergency settings so that appropriate services can be directed towards them.

Objective: to evaluate whether the Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR) predicts the clinical outcomes and health and social services costs of older people discharged from acute medical units.

Design: an observational cohort study using receiver–operator curve analysis to compare baseline ISAR to an adverse clinical outcome at 90 days (where an adverse outcome was any of death, institutionalisation, hospital readmission, increased dependency in activities of daily living (decrease of 2 or more points on the Barthel ADL Index), reduced mental well-being (increase of 2 or more points on the 12-point General Health Questionnaire) or reduced quality of life (reduction in the EuroQol-5D) and high health and social services costs over 90 days estimated from routine electronic service records.

Setting: two acute medical units in the East Midlands, UK.

Participants: a total of 667 patients aged ≥70 discharged from acute medical units.

Results: an adverse outcome at 90 days was observed in 76% of participants. The ISAR was poor at predicting adverse outcomes (AUC: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.54–0.65) and fair for health and social care costs (AUC: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.59–0.81).

Conclusions: adverse outcomes are common in older people discharged from acute medical units in the UK; the poor predictive ability of the ISAR in older people discharged from acute medical units makes it unsuitable as a sole tool in clinical decision-making.

Keywords: older people, acute care, screening

Introduction

Most UK acute hospitals operate a system whereby medical patients admitted for non-elective care are assessed on an acute medical unit (AMU) [1]. AMUs have an important role in triage—identifying those patients that require in-patient care and those who might be safely managed in the community setting. Some older people presenting to an acute medical unit who are discharged directly have poor outcomes and high resource use: in one series 58% subsequently re-presented to the AMU and 29% died over the subsequent 12 months [2].

These observations have led to the development of services based on acute medical units to deal with frail older patients [3]. For such services to be cost-effective, it is important to focus the intervention on a cohort of patients at risk of adverse outcomes that are likely to benefit. A review [4] of tools to do this showed that only the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) [5] (see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix S1) had evidence that it predicted a wide range of adverse health outcomes including death, institutionalisation, readmission, resource use and decline in physical or cognitive function. The ISAR includes six simple dichotomous questions, making it simple and acceptable for patients and staff alike. The ISAR has been tested in North America [6], many European countries [7–11] and Hong Kong [12] where its predictive value varied between ‘fair’ and ‘poor’ [determined using receiver–operator curve (ROC) analysis which takes both specificity and sensitivity into account], the difference depending upon the case mix and the health services available in different countries. For the ISAR to be used in the UK, it is important to demonstrate adequate predictive ability in UK settings, but this has not yet been done, and this was the purpose of this study.

Methods

Design

A two centre, observational cohort study in Nottingham and Leicester, East Midlands, UK was conducted comparing baseline ISAR scores to clinical outcomes and health service costs over 90 days following discharge from AMUs.

Participants

Recruitment was over 23 months from January 2009 (Nottingham January 2009–April 2010, Leicester December 2009–November 2010), and was performed by research staff embedded in the acute medical units during week-day office hours. Participants were recruited after a decision to discharge had been made by the medical team, and before they left hospital.

Patients were eligible if they were resident in the hospital catchment area, were ≥70 years and were expected to be discharged from the AMU within <72 h. Initially, patients were excluded if they lacked mental capacity to give informed consent and if there was no family consultee available. An amendment was subsequently approved in March 2010 by the research ethics committee to permit such potential participants to be recruited subject to agreement by the responsible physician. Other exclusion criteria were if staff advised against approaching the patient, or if neither the patient nor carer could communicate in English sufficiently to complete baseline assessments.

Baseline measurements

The ISAR score was completed by the researcher on recruitment. Other baseline variables included:

age, gender, residential status;

comorbidity—Charlson comorbidity index [13], a comorbidity score derived from a weighted list of medical conditions;

prescribed medications;

frailty—study of osteoporotic fractures index (SOF) [14], a 3-point scale;

malnutrition risk assessment—Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) [15], a six-item tool;

cognitive function—Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [16], a 30-point scale;

dependency in personal activities of daily living—Barthel ADL Index [17], a 10-item scale from 0 to 20;

quality of life—EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D) [18], a 5-item scale ranging from –0.59 to 1.0;

mental well-being—General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) [19], a 12-item tool ranging from 0 to 36, where lower scores denote better mental well-being.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes were ascertained at 90 days. After checking hospital and GP records for deaths and moves of addresses, outcomes were determined using postal questionnaires, with further checks of hospital and GP records, telephone prompts and home visits for those not returning questionnaires within 2 weeks.

A composite adverse outcome was defined as any of the following during the follow-up:

death;

hospital readmission;

new entry into a care home or change of care home;

increased dependency in personal activities of daily living, defined as a decrease of ≥2 points on the Barthel ADL index;

reduced mental well-being, defined as an increase of ≥2 points on the GHQ-12;

reduced quality of life, defined by any decline in EQ-5D.

Health and social service costs

Health service resource use during the 90-day follow-up period was obtained by electronic extraction from routine databases: acute and subacute hospitals (including in-patient and day case lengths of stay); primary care (type of contact, procedures and drug prescription); ambulance services (dispatch category, call outs and those conveyed); intermediate care services (type and number of contacts) and mental health services (type and number/duration of contacts). Social service resource use was also obtained from service databases (contacts and services).

Complete health and social service resource use data were obtained only from the Nottingham cohort, because regulatory permission to access these data was granted only for this site. Within this cohort, general practice data were obtained for the subset of participants where general practitioners gave permission for their data to be extracted. Personal costs were not measured.

The resource use data were combined into one database to allow derivation of an overall cost for each participant. Costs were determined by applying standard NHS [20] and social care [21] reference costs in pounds sterling to the resource use data.

Sample size

A sample size of 700 was chosen to estimate the sensitivity of the ISAR tool to within 12% and the specificity to within 4% using 95% confidence intervals for these proportions, assuming an adverse outcome in 10% based on previous series [2].

Analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the study population and their clinical outcomes. Differences in participant characteristics at recruitment according to the conventional ISAR cut-off point of 2 were explored using t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. The diagnostic value of the ISAR tool for the composite adverse clinical outcome was analysed using a ROC to compare the sensitivity and specificity of different ISAR cut-off values to detect adverse outcomes. The positive and negative predictive values for different ISAR cut-off values were also calculated. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to describe the precision of the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value estimates. ROC analyses were performed for each component of the composite adverse outcome. The area under the curve (AUC) was interpreted, where 0.90–1.00 = excellent, 0.80–0.89 = good, 0.70–0.79 = fair, 0.60–0.69 = poor and 0.50–0.59 = no value.

Unit costs were applied to resource use data. The total costs of health and social care resource use were compared between participants with complete resource use data who scored <2 or ≥2 on the ISAR, using non-parametric bootstrapping in the view of the highly skewed distribution [22]. The discriminatory value of the ISAR to identify participants with high total health and social costs was explored using an ROC analysis, in which the sensitivity and specificity of the ISAR to predict a participant in the top 10% of total health and social care costs was calculated.

Stata version 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

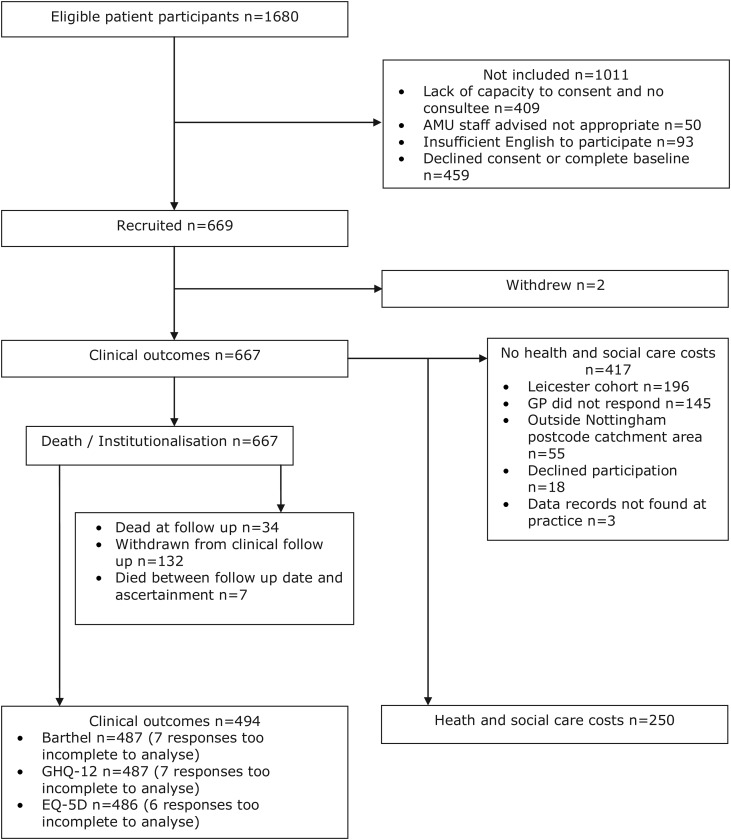

A total of 667 (40%) participants were recruited from 1,680 eligible patients: 409 (24%) were not recruited due to the lack of mental capacity and lack of a consultee and 459 (27%) declined to be recruited. Four hundred and seventy-one participants were recruited in Nottingham (71%) and 196 from Leicester (29%). Death and residential status were ascertained for all 667 participants, and re-admission was ascertained for 644 participants. Of 667, 132 (20%) withdrew from ascertainment of clinical outcomes at 90 days (23 gave explicit withdrawal, 20 were too ill to complete the outcome questionnaire and 89 did not respond). See the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

ISAR characteristics

Four hundred and sixty-two participants (69%) had an ISAR score of 2 or more. Of the questions making up the ISAR score, 118 participants (18%) had serious problems with memory, 165 participants needed more help than usual to take care of themselves since the acute illness (25%), 170 participants had sight problems (25%), 259 needed help on a regular basis before the acute illness (39%), 303 had been hospitalised in the past 6 months (45%) and 519 were taking more than three medications per day (78%).

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics according to the ISAR cut-off point of 2 or more are shown in Table 1. Participants with an ISAR score of 2 or more were older, more likely to be female, more likely to be widowed, more likely to be cognitively impaired, more dependent in activities of daily living, had higher scores on the GHQ-12, lower EQ-5D quality of life scores, were more likely to be malnourished or at risk of malnourishment and more likely to be classified as frail.

Table 1.

Participant baseline characteristics by the ISAR score

| ISAR <2 (n = 205) | ISAR ≥2 (n = 462) | Total (n = 667) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 78 (73–83) | 81 (76–85) | 80 (75–85) |

| Female+ (%) | 107 (52.2) | 279 (60.4) | 386 (57.9) |

| Residence* (%) | |||

| Lives alone | 85 (41.5) | 224 (48.5) | 309 (46.3) |

| Lives with spouse, partner | 116 (56.6) | 203 (43.9) | 319 (47.8) |

| Lives in care home | 4 (2.0) | 35 (7.6) | 39 (5.9) |

| White ethnicity | 200 (97.6) | 447 (96.8) | 647 (97) |

| Marital status* (%) | |||

| Married/partner | 113 (55.1) | 181 (39.2) | 294 (44.1) |

| Divorced/separated | 13 (6.3) | 34 (7.4) | 47 (7.1) |

| Widowed | 61 (29.8) | 219 (47.4) | 280 (42.0) |

| Never married | 16 (7.8) | 21 (4.6) | 37 (5.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0) | 7 (1.5) | 9 (1.4) |

| Charlson co-morbidity score* | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Diagnosis of dementia* (%) | 2 (1.0) | 32 (6.9) | 34 (5.1) |

| Presented with (%) | |||

| Fall | 48 (23.4) | 113 (24.5) | 161 (24.1) |

| Reduced mobility | 14 (6.8) | 46 (10.0) | 60 (9.0) |

| New or increased continence disorder | 1 (0.5) | 5 (1.1) | 6 (0.9) |

| Current pressure sores | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

| MMSE score* | 28 (27–30) | 27 (24–29) | 28 (25–29) |

| MMSE >24* (%) | 177 (86.3) | 346 (74.9) | 523 (78.4) |

| EQ-5D score* | 202 0.74 (0.66–0.85) | 450 0.62 (0.28–0.76) | 652 0.69 (0.36–0.80) |

| GHQ12 score* | 205 9 (7–11) | 453 12 (9–16) | 658 11 (8–15) |

| Barthel ADL score* | 205 20 (18–20) | 455 18 (16–19) | 660 18 (17–20) |

| Nutritional screening* (MNA) (%) | |||

| Malnourished/at risk of malnourishment | 38 (18.5) | 173 (37.4) | 211 (31.6) |

| Normal | 165 (80.5) | 274 (59.3) | 439 (65.8) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0) | 15 (3.3) | 17 (2.6) |

| SOF frailty* (%) | |||

| Robust | 31 (15.1) | 21 (4.6) | 52 (7.8) |

| Pre-frail | 70 (34.2) | 94 (20.4) | 164 (24.6) |

| Frail | 96 (46.8) | 331 (71.7) | 427 (64.0) |

| Unknown | 8 (3.9) | 16 (3.5) | 24 (3.6) |

Median (IQR) presented for continuous and scaled variables. Frequency and percentage presented for categorical variables.

+P-value < 0.05, *P-value < 0.01.

Outcomes at 90 days

At 90 days, 34 (5%) participants had died and 6 (1%) of the 633 surviving participants had moved to a care home. One hundred and seventy-two (27%) of 644 for whom data were available had an unplanned re-admission.

Clinical outcomes were ascertained for 494 (78%) of the 633 participants alive at 90 days. A greater proportion of participants who withdrew from ascertainment of clinical outcomes at follow-up were female (66 versus 56%), not married (68 versus 53%), had ISAR scores of 2 or more (77 versus 67%), were cognitively impaired (MMSE ≤24, 33 versus 19%), had lower EQ-5D quality of life scores (medians 0.64 versus 0.69) at baseline and had an unplanned readmission during the follow-up period (38 versus 24%).

The composite adverse outcome was observed in 399 (76%) of the 528 participants who died (n = 34) or had clinical outcome data revealing an increase in dependency in 20% (97/481), reduced mental well-being in 46% (220/484) and reduced quality of life in 49% (236/484): two hundred and twenty-three participants (42%) had two or more individual adverse outcomes.

Performance of the ISAR tool for detecting adverse outcomes

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the composite adverse outcome was ‘poor’ −0.60 (95% confidence interval 0.54–0.65, Table 2). The AUCs for individual adverse outcomes were ‘poor’ for death, care home admission, readmission and increased dependency. AUCs were ‘of no value’ for deterioration in mental well-being or quality of life (Table 2).

Table 2.

Receiver-operating characteristics analysis of the ISAR tool for detecting adverse outcomes

| Adverse outcome | Frequency (%) | ISAR ≥2, n (%) | Receiver-operating characteristic analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |||

| Death | 34/667 (5) | 462 (69) | 85 (69, 95) | 32 (28, 35) | 6 ( 4, 9) | 97 (94, 99) | 0.62 (0.53, 0.71) |

| Move to care homea | 6/633 (1) | 433 (68) | 83 (36, 100) | 32 (28, 36) | 1 ( 0, 3) | 99 (97, 100) | 0.65 (0.40, 0.91) |

| Readmission | 172/644 (27) | 446 (69) | 76 (69, 82) | 33 (29, 38) | 29 (25, 34) | 79 (73, 84) | 0.60 (0.55, 0.65) |

| Increase in dependencyb | 97/481 (20) | 315 (65) | 79 (70, 87) | 38 (33, 43) | 24 (19, 30) | 88 (82, 92) | 0.62 (0.56, 0.68) |

| Reduced mental wellbeingb | 220/484 (46) | 317 (66) | 65 (59, 72) | 34 (28, 40) | 45 (40, 51) | 54 (46, 62) | 0.50 (0.45, 0.56) |

| Reduced quality of lifeb | 236/484 (49) | 318 (66) | 72 (66, 78) | 40 (34, 47) | 53 (48, 59) | 60 (52, 68) | 0.56 (0.51, 0.61) |

| Any adverse outcomec | 399/528 (76) | 355 (67) | 71 (66, 75) | 43 (34, 52) | 79 (74, 84) | 32 (25, 40) | 0.60 (0.54, 0.65) |

| High total health and social care costsd | 25/250 (10) | 173 (69) | 88 (69,97) | 33 (27, 39) | 13 (8,19) | 96 (89, 99) | 0.70 (0.59, 0.81) |

CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under curve.

aFor participants surviving to the end of the follow-up period.

bFor participants surviving to the end of the follow-up period and completing clinical follow-up.

Change missing for 13 participants for ADL, 10 participants for GHQ and 10 participants for EQ-5D due to incomplete responses at baseline or follow-up.

cAny adverse outcomes defined as death, move to care home, readmission, increase in dependency, reduced mental wellbeing or reduced quality of life for participants who died during the study or completing clinical follow-up.

dParticipants in the top 10% of health and social (secondary, primary, intermediate and social) care costs.

Costs

Data from acute and subacute hospitals, ambulance services, intermediate care services, mental health services and social services were obtained for all 471 participants in the Nottingham cohort. The 471 participants were registered with 118 general practices, of whom 48 gave permission for their data to be extracted. Reasons why data were not obtained were: no response by practice to enquiries by research team (n = 145 participants); practice located outside the Nottingham postcode catchment area (n = 55 participants); practice expressly declined to provide data (n = 18 participants) or patient not registered with the stated practice (n = 3 participants). This provided general practice data and hence total health and social care costs for 250/471 (53%) participants recruited in Nottingham.

Total mean health and social costs were higher in the group with ISAR ≥2 (£2331, 95% CI: £1889–£2885, n = 173) than in the group with ISAR <2 (£1278, 95% CI: £862–£2442, n = 77), this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.018, t-test). The AUC for discriminating patients with high health and social care costs (highest 10%) was fair (AUC: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.59–0.81) (Table 2).

Discussion

Three quarters (76%) of older patients discharged from acute medical units had one or more adverse outcomes (death, institutionalisation, readmission, an increase in dependency or a decrease in mental well-being or quality of life) by 3 months. However, despite significances between the baseline health status of patients with ISAR scores above and below the cut-off level, the ability of the ISAR to predict adverse outcomes was poor, and its ability to predict health and social care costs was fair.

A large proportion of potential participants were not recruited, partly due to methodological issues related to the ability of potential participants who lacked mental capacity to give informed consent. As a result, patients with the worst outcomes were likely to have been excluded. Furthermore, a sizable proportion (20%) of those recruited declined ascertainment of clinical outcomes despite the protocol offering postal, telephone or face-to-face follow-up, and these patients tended to have more adverse characteristics than those in whom clinical outcomes were ascertained. Despite these two factors, the incidence of adverse outcomes was much higher than the 10% used for the sample size calculation, which will have increased the power of the study. However, exclusion of those who were probably at high risk (incapable, no consultee) would have increased sensitivity and reduced specificity, but the exclusion of low-risk people (who came and went quickly) would have had the reverse effect. This might have affected the overall discriminatory value.

Thus, we believe that the estimates of the ISAR to predict such adverse outcomes are broadly correct. The cost analyses were carried out in a smaller cohort than originally intended due to the inability to acquire resource use data from both centres and for all participants, but despite this a significant difference in costs between ISAR groups was seen.

Baseline and outcome questions were in multiple choice answer formats to reduce the potential for bias as the baselines scores were collected by researchers and the clinical outcome scores were collected by participants/carers.

This study is the first to study the ISAR in the UK. Our finding, that the ISAR has a poor discriminating value to predict adverse outcomes in older patients discharged from UK acute medical units, shows that the ISAR did not perform as well as in the original Canadian study [6], where the tool was shown to be ‘fair’ discriminating value (AUC: 0.71). However, our findings are compatible with more recent European and Asian studies [7–12] which have reported areas under the curves for the ISAR between ‘no value’ (0.5) and ‘fair’ (0.7). As our study only evaluated the ‘best’ 40%, further studies are warranted taking ‘all comers’ before the utility of this tool can be judged.

The fact that the ISAR has only poor predictive ability does not mean that it has no clinical value. Clearly, the ISAR is not suitable as a single tool in clinical decision-making such as to identify people suitable for specialist services—used alone it will miss many at high risk and misclassify as high risk many who are at low risk. However, given that the clinical issues related to the care of vulnerable older people are characterised by complexity, it is unlikely that any single simple tool will ever be found that has excellent or good predictive properties. Thus, the ISAR could be used as a standardised adjunct to clinical decision-making and recording, or as an indicator of case mix for service monitoring purposes, and in the stratification and selection process for patients in clinical trials. Given the limitation of such tools, further work is required to devise a simple, clinically acceptable process to identify high-risk patients. Such a process may require clinical judgment alongside simple standardised tools such as the ISAR.

Key points.

Tools are required to identify high-risk older people in acute emergency settings so that appropriate services can be directed towards them.

The ISAR tool was poor at predicting adverse outcomes and fair for health and social care costs.

The ISAR in older people discharged from acute medical units is unsuitable as a sole tool in clinical decision-making.

Authors' roles

All authors have contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. J.E.: contributor to study design, conduct, analysis; L.B.: analysis; J.R.F.G.: Principal Investigator, guarantor, contributor to design, conduct, analysis; M.F.: collection, methodology, and analysis of cost and resource use data; V.B.: methodology and analysis of cost and resource use data; R.E.: grantholder, contributor to study design; S.P.C. had initial idea for study, grant holder, contributor to study design, study conduct, analysis.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf.

Ethical approval

Research ethics committee and local regulatory approvals were obtained (08/H0502/139).

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407-10147). The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements

Support for the recruitment of participants was obtained from Tony Stevens and the Trent and Leicester & Northampton Comprehensive Local Research Networks (Trent: Rachael Taylor, Clare Litherland, David Trevor, Mick Backner; Leicester and Northampton: Aidan Dunphy, Hilda Parker). The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Loraine Buck for helping recruit GP practices to participate in the study, Georgios Gkountouras for helping assign unit costs to secondary care and Melanie Titze for applying unit costs to the medication audit data. We would also like to thank the primary care trusts, general practices (unfortunately there are too many names to list), IT services at Nottingham University Hospitals and Kingsmill Hospital (Kate Moore, Rebecca Stevens and Samantha Cole), IT services in Leicester (Iain Sands), EMAS (Darren Coxon and Stacey Knowles), MHT (Lawrence Flatman), Intermediate care (Elaine Humber and Carol Foster) and the patient participants in the study. The authors would also like to acknowledge the wider Medical Crises in Older People study group which included Rowan Harwood, Anthony Avery, Sarah Lewis, Davina Porock, Rob Jones, Pip Logan, Justine Schneider, Jane Dyas, Adam Gordon, Sarah Goldberg, Bella Robbins.

References

- 1.Percival F, Day N, Lambourne A, Derek B, Ward D. An Evaluation of Consultant Input into Acute Medical Admissions Management in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodard J, Gladman J, Conroy S. Frail Older People at the Interface. JNHA. 2009;13((Suppl. 1): S308) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmans J, Conroy S, Harwood R, et al. Evaluation of comprehensive geriatric assessment compared with standard care, for older people scoring positive on a risk screening tool (‘Identification of Seniors At Risk’), who are discharged within 72 hours of attending an acute medical unit with a medical crisis. Trials. 2011;12:200. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmans JA, Gladman JRF, Havard D. Umbrella review of tools to assess risk of poor outcome in older people attending acute medical units (2012). Medical Crises in Older People Discussion paper series. issue 11 June http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/mcop/documents/papers/issue11-mcop-issn2044-4230.pdf. (23 April 2013, date last accessed)

- 5.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S, Verdon J, Ardman O. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1229–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Belzile E, Verdon J. Prediction of hospital utilization among elderly patients during the 6 months after an emergency department visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:438–45. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.110822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvi F, Morichi V, Grilli A, et al. Screening for frailty in elderly emergency department patients by using the Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR) J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:313–8. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Bari M, Salvi F, Roberts AT, et al. Prognostic stratification of elderly patients in the emergency department: a comparison between the ‘Identification of Seniors at Risk’ and the ‘Silver Code’. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:544–50. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deschodt M, Wellens NIH, Braes T, et al. Prediction of functional decline in older hospitalized patients: a comparative multicenter study of three screening tools. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;23:421–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03325237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buurman BM, van den Berg W, Korevaar JC, Milisen K, de Haan RJ, de Rooij SE. Risk for poor outcomes in older patients discharged from an emergency department: feasibility of four screening instruments. Eur J Emerg Med. 2011;18:215–20. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328344597e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braes T, Moons P, Lipkens P, et al. Screening for risk of unplanned readmission in older patients admitted to hospital: predictive accuracy of three instruments. Aging Clin Exper Res. 2010;22:345–51. doi: 10.1007/BF03324938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yim VWT, Rainer TH, Graham CA, Woo J, Lan FL, Ting SM. Emergency department intervention for high-risk elders: identification strategy and randomised controlled trial to reduce hospitalisation and institutionalisation. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;13(Suppl. 3):4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleves MA, Sanchez N, Draheim M. Evaluation of two competing methods for calculating Charlson's comorbidity index when analyzing short-term mortality using administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:903–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, et al. for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:382–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the Short-Form Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA-SF) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–72. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.m366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF FS, McHugh PR. Mini mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wade D, Collin C. The Barthel ADL index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Dis Studies. 1988;10:64–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brazier J, Walter SJ, Nicholl JP, Kohler B. Using the SF-36 and Euroqol on an elderly population. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:195–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00434741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg D, Hiller V. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Physiol Med. 1979;9:139–45. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UK Department of Health. NHS reference costs Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_131140. (23 April 2013, date last accessed).

- 21.Curtis L. 2010. Unit costs of health and social care PSSRU.

- 22.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med. 2000;19:3219–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001215)19:23<3219::aid-sim623>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.