Abstract

Background

Insulin may promote breast cancer directly by stimulating the insulin receptor or indirectly by increasing the plasma concentration of active sex hormones. The association between insulin and breast density, a strong breast cancer risk factor, has not been thoroughly studied. We measured associations between c-peptide (a molar marker of insulin secretion), breast cancer risk, and breast density measurements in case-control studies nested within the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II cohorts.

Methods

Breast cancer associations were estimated with multivariate logistic regression models and then pooled across cohorts (total n=1,084 cases and 1,785 controls). Mammographic density associations (percent dense area, dense area, and non-dense area) were estimated as the difference in least-square means of the density parameters between quartiles of c-peptide concentration in all breast cancer controls with available screening mammography films (n=1,469).

Results

After adjustment for adiposity, c-peptide was not associated with any measure of breast density. However, c-peptide was associated with an approximately 50% increased risk of invasive breast cancer (top vs. bottom quartile, adjusted OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.1, 2.0) that was robust to adjustment for plasma free estradiol and SHBG. The association was stronger for ER-negative disease (adjusted OR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.2, 3.6).

Conclusions

Our data suggest a positive association between hyperinsulinemia and breast cancer risk that occurs through non-estrogenic mechanisms, and that is not mediated by breast density.

Impact

Primary prevention of breast cancer in women with hyperinsulinemia may be possible by targeting insulin signaling pathways.

Introduction

Insulin has been hypothesized to promote breast tumor growth by stimulating the insulin receptor and by increasing the bioavailability of active sex hormones through attenuated expression of sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) (1). Insulin and c-peptide are produced by enzymatic cleavage of proinsulin. C-peptide’s one-to-one stoichiometry with insulin in this reaction and its longer circulating half-life make it an appealing plasma marker of insulin secretion (2). Several earlier studies of insulin or c-peptide in relation to breast cancer risk suggested a positive association, though some were impaired by imprecise association estimates or the collection of samples after breast cancer diagnosis (3-11). Several other studies showed no evidence for a positive association between c-peptide or insulin and breast cancer risk (12-18), and two reports suggest that a positive association exists only with postmenopausal breast cancer (19,20). A 2008 meta-analysis of this topic reported a modest positive association (summary relative risk=1.26, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.48), but observed heterogeneity by study design and did not stratify estimates by menopausal status at diagnosis (21).

Mammographic breast density is one of the strongest known predictors of breast cancer risk (22). Independent associations have been reported between dense and non-dense breast area and breast cancer incidence, with greater dense area consistently associated with higher risk (23,24). Greater non-dense area has been associated with both lower (23) and higher (24) risk. Only two studies have evaluated the association between plasma insulin or c-peptide level and percent dense area on mammogram, and both showed no association (25,26).

Our objective was to evaluate the association between plasma c-peptide concentration and breast dense area, non-dense area, percent dense area, and breast cancer risk in prospective case-control studies nested within the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II cohorts.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and all subjects consented to participate.

Source population: Nurses’ Health Study

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) began in 1976 with the enrollment of 121,700 female U.S. registered nurses between the ages of 30 and 55. Participants returned a baseline questionnaire to report medical history and reproductive information. New data have been collected biennially to update exposures and ascertain new diagnoses, and the response rate at each questionnaire cycle has been approximately 90 percent. In 1989 and 1990, 32,826 NHS participants provided blood samples for measurement of genetic and plasma biomarkers. For this analysis we used a breast cancer case-control study nested within the NHS blood sub-cohort, consisting of women diagnosed with invasive or in situ disease between 1990 and 1996 and matched controls. Eligible controls were identified from the risk set of each case, with index dates defined as the date of the matched case’s diagnosis. One or two controls were matched to each case on age (±2 years), menopausal status, current use of postmenopausal hormones (PMH), and the month, time of day (in 2-hour increments), and fasting status (≥8 hours vs. otherwise) at the time of blood collection.

Associations between circulating c-peptide level and incident breast cancer were evaluated for 762 cases and 1,146 matched controls. Associations between c-peptide and mammographic density measurements were estimated in the 993 NHS breast cancer controls with available mammography films and data on c-peptide. Films from screening mammograms conducted close to the date of blood draw were requested from the 2,857 controls who were alive at the start of collection. Collection permission was granted by 2,512 controls, from whom we successfully obtained 2,406 films. We excluded 35 women whose mammography dates were after, or within the month preceding, a breast cancer diagnosis. Another 9 women were excluded because they provided premenopausal mammography films but were diagnosed with breast cancer while postmenopausal. Of the remaining 2,362 women with mammography data, 993 also had data on c-peptide.

Source population: Nurses’ Health Study II

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) began in 1989 with the enrollment of 116,430 female U.S. registered nurses between the ages of 25 and 42 (27). NHSII participants also complete biennial questionnaires (~90% response rate per cycle), and a subset of 29,611 women provided blood samples between 1996 and 1999. We used a breast cancer case-control study nested within the NHSII blood sub-cohort to assess the association between c-peptide levels and breast cancer incidence [as previously reported in a stand-alone NHSII study (18)] to obtain a more precise estimate of this association by combining data from the two Nurses’ Health Study cohorts. Between the blood collection and the end of 2005 we ascertained 322 incident cases of invasive and in situ breast cancer confirmed by medical record review. To these cases were matched 639 controls on age (±2 years), menopausal status, current use of PMH, and month, time of day (in 2-hour increments) and fasting status (≥8 hours vs. otherwise), all defined at the time of blood collection.

Associations between c-peptide levels and mammographic density measurements were evaluated in the 476 NHSII breast cancer controls with available mammography films and data on c-peptide. Films from screening mammograms conducted close to the date of blood draw were requested from 1,593 controls who were alive at the start of collection. We successfully obtained 1,223 films from controls. We excluded 11 women whose mammography dates were after, or within the month preceding, a breast cancer diagnosis. Another 85 women were excluded because they provided premenopausal mammography films but were diagnosed with breast cancer while postmenopausal. Of the remaining 1,077 women with mammography data, 476 also had data on c-peptide. The earlier report of c-peptide and breast cancer risk in NHSII did not evaluate mammographic density (18).

Measurement of plasma c-peptide, estradiol, and sex hormone binding globulin concentrations

Collection, processing, and storage of NHS and NHSII blood specimens is described in detail elsewhere (28). Briefly, whole blood samples were shipped overnight on ice and separated into plasma, erythrocyte, and leukocyte fractions upon arrival at our laboratory. Aliquots from these fractions were placed in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen units until assay. C-peptide was assayed from plasma samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratory, Webster, TX) in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Pollak (McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada). Free estradiol and SHBG were measured only in the subset of NHS subjects who were both postmenopausal and not using postmenopausal hormones (PMH) at the time of blood draw. Estradiol assays were conducted at the Nichols Institute (Quest Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, California, USA), and methods are detailed elsewhere (29). Briefly, estradiol was assayed by radioimmunoassay preceded by organic extraction and celite chromatography. Two batches of SHBG measurement were carried out by the University of Massachusetts Medical Center’s Longcope Steroid Radioimmunoassay Laboratory (Worcester, MA) with an immunoradiometric kit (Orion Corporation, Turku, Finland). All other SHBG measurements were carried out by the Reproductive Endocrinology Unit Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA) using the AxSYM Immunoassay System (Abbott Diagnostics, Worcester, MA). For each of these analytes, matched case/control sets were assayed in duplicate or triplicate in the same batch, and laboratory personnel were blinded to the case/control status of all samples. Coefficients of variation (CVs) for c-peptide measurement ranged from 2.8 to 11.6 (mean=6.6) over four assay batches; CVs for free estradiol ranged from 3.6 to 18.3 (mean=11.6) over four assay batches; and CVs for SHBG ranged from 3.3 to 21.9 (mean=8.6) over eight assay batches.

Measurement of mammographic breast density

A methodology of mammographic breast density measurement in the NHS and NHSII participants is reported in an earlier publication (30). To summarize, craniocaudal views of both breasts were digitized with a Lumisys 85 digital film scanner (Lumisys, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). We used Cumulus software (University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada) for computer-assisted threshold determination and measurement of dense area, non-dense area (dense area subtracted from total area), and percent dense area (dense area divided by total area) in each breast. Analyses of these measurements were based on values averaged across left and right breasts. There were 2 batches of density readings, each of which included random replicate mammograms to assess reader reliability. The mammogram reader was blinded to subjects’ case/control status and biomarker data. Replicate mammograms from each batch of density reading exhibited within-person intra-class correlation coefficients of ≥0.90.

Definitions of analytic variables

Plasma c-peptide concentrations were characterized as batch-specific quartiles due to inter-batch variability. Quartiles were represented by three design variables in regression models, with the first quartile serving as the reference category. Age at blood draw, age at menarche, waist to hip circumference ratio (WHR) at blood draw, breast dense area, non-dense area, and percent dense area were modeled as continuous variables. Body mass index at time of blood draw was represented by 13 design variables in regression models (see footnote to Table 2 for categories) to accommodate nonlinear effects of BMI. Menopausal status at blood draw and postmenopausal hormone (PMH) usage were combined into a single variable and modeled with design variables representing the following levels: premenopausal, postmenopausal/never used PMH, postmenopausal/ formerly used PMH, and postmenopausal/ currently using PMH. Alcohol intake was defined as the cumulative average daily consumption between the first year of alcohol assessment by questionnaire (1980 for NHS and 1989 for NHSII) and the follow-up cycle closest to the year of blood draw (1990 for NHS and 1995 for NHSII). Average alcohol intake was then summarized by the following categories, which were modeled as design variables: 0 (reference), 0.1—4.9, 5.0—9.9, 10—19.9, and ≥20 grams/day.

Table 2.

Associations between quartiles of c-peptide concentration and measures of mammographic breast density among controls, Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study 2 combined (n=1,469). Associations are reported as difference in least-square means (95% confidence intervals) between quartiles of plasma c-peptide concentration, with reference to the first quartile.

| Quartile of plasma c-peptide concentration (ng/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

| All women | ||||

| n=371 | n=393 | n=365 | n=340 | |

| Percent dense area: | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 38.6 (21.0) | 33.8 (20.4) | 26.7 (19.7) | 23.6 (19.7) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | −4.7 (−7.4, −2.0) | −10 (−13, −7.2) | −14 (−17, −11) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | −4.2 (−7.0, −1.4) | −8.6 (−11, −5.7) | −14 (−17, −11) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | −1.3 (−3.9, 1.2) | −1.2 (−4.0, 1.5) | −1.9 (−5.0, 1.2) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | −1.2 (−5.1, 2.7) | −1.0 (−5.1, 3.1) | −1.5 (−6.4, 3.4) |

| Dense area (cm 2 ): | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 53.2 (40.1) | 52.6 (43.9) | 44.8 (37.8) | 41.6 (37.9) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | −0.04 (−5.1, 5.0) | −3.1 (−8.2, 2.1) | −7.7 (−13, −2.4) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | 1.9 (−3.0, 6.8) | −3.3 (−8.4, 1.8) | −9.2 (−15, −3.8) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 3.1 (−1.9, 8.0) | 1.0 (−4.4, 6.3) | 1.3 (−4.7, 7.3) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | 3.0 (−4.2, 10) | 0.9 (−6.7, 8.6) | 1.2 (−8.4, 11) |

| Non-dense area (cm 2 ) | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 91.7 (65.7) | 110 (74.5) | 138 (83.5) | 161 (95.0) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | 20 (9.6, 30) | 49 (39, 60) | 73 (63, 84) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | 21 (11, 31) | 41 (30, 51) | 72 (61, 83) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 8.7 (0.4, 17) | 8.2 (−0.8, 17) | 13 (2.9, 23) |

| Multivariate + BMI +WHR4 | 0. ref | 8.0 (−6.3, 22) | 6.8 (−8.8, 22) | 10 (−7.3, 28) |

| Premenopausal women | ||||

| n=105 | n=131 | n=82 | n=93 | |

| Percent dense area: | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 44.2 (20.1) | 41.6 (20.0) | 38.2 (20.8) | 33.2 (22.8) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | −2.4 (−7.6, 2.8) | −6.4 (−12, −0.5) | −11 (−16, −5.0) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | −1.8 (−7.1, 3.4) | −4.9 (−11, 1.1) | −12 (−18, −6.0) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 1.4 (−3.2, 6.0) | 4.0 (−1.4, 9.4) | 1.9 (−3.9, 7.7) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | 1.8 (−20, 24) | 4.6 (−18, 27) | 2.5 (−20, 25) |

| Dense area (cm 2 ): | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 68.1 (41.3) | 76.4 (51.4) | 72.7 (42.7) | 65.9 (47.8) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | 10 (−1.1, 21) | 6.4 (−6.4, 19) | −0.5 (−13, 12) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | 11 (−0.1, 22) | 1.7 (−11, 14) | −2.5 (−15, 9.9) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 11 (0.2, 22) | 4.7 (−8.0, 17) | 9.5 (−4.2, 23) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | 11 (−42, 63) | 4.5 (−48, 57) | 9.2 (−44, 63) |

| Non-dense area (cm 2 ) | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 99.3 (74.2) | 122.8 (87.8) | 144.8 (98.2) | 159.9 (98.4) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | 25 (4.3, 46) | 51 (28, 74) | 61 (39, 84) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | 23 (3.6, 43) | 36 (13, 59) | 63 (40, 86) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 7.9 (−8.5, 24) | −2.1 (−21, 17) | 5.0 (−16, 26) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | 4.9 (−100, 110) | −6.0 (−113, 101) | −0.9 (−103, 105) |

| Postmenopausal women | ||||

| n=229 | n=220 | n=248 | n=219 | |

| Percent dense area: | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 35.3 (21.0) | 28.4 (18.7) | 22.7 (17.7) | 18.9 (16.2) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | −6.2 (−9.6, −2.9) | −11 (−14, −7.8) | −15 (−19, −12) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | −5.7 (−9.1, −2.2) | −9.6 (−13, −6.1) | −15 (−18, −11) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | −2.5 (−5.8, 0.7) | −3.3 (−6.7, 0.05) | −3.2 (−7.0, 0.64) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | −2.5 (−7.7, 2.6) | −3.5 (−8.9, 1.8) | −3.3 (−9.1, 2.5) |

| Dense area (cm 2 ): | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 45.9 (38.3) | 37.9 (32.3) | 35.3 (31.2) | 31.1 (28.0) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | −5.6 (−11, 0.03) | −7.0 (−12, −1.4) | −11 (−17, −5.3) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | −2.6 (−8.2, 3.1) | −5.0 (−11, 0.6) | −11 (−17, −4.7) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | −0.8 (−6.5, 5.0) | −1.2 (−7.2, 4.8) | −1.3 (−8.0, 5.4) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | −0.8 (−9.7, 8.0) | −1.6 (−10, 7.3) | −1.7 (−12, 8.4) |

| Non-dense area (cm 2 ) | ||||

| Mean (sd) | 88.8 (61.3) | 105 (65.7) | 135 (77.3) | 164 (93.9) |

| Age adjusted1 | 0. ref | 19 (6.5, 32) | 49 (36, 61) | 81 (68, 94) |

| Multivariate2 | 0. ref | 21 (9.0, 34) | 43 (31, 55) | 78 (65, 91) |

| Multivariate + BMI3 | 0. ref | 10 (−0.4, 20) | 14 (3.5, 25) | 19 (6.7, 31) |

| Multivariate + BMI + WHR4 | 0. ref | 9.9 (−7.3, 27) | 14 (−3.1, 32) | 18 (−1.6, 38) |

Adjusted for age at blood draw (continuous) and batch of mammographic density reading (random effect).

Adjusted for all of the above and for age at menarche (continuous), menopausal/PMH status at blood draw (design variables: premenopausal, postmenopausal never used PMH, postmenopausal formerly used PMH, postmenopausal currently using PMH), cumulative average daily alcohol intake (design variables: 0, 0.1 to 4.9, 5.0 to 9.9, 10 to 19.9, ≥20 g/day), and fasting status at blood collection (≥8 hours or <8 hours).

Adjusted for all of the above and for BMI at blood draw (13 design variables: <20.0, whole number categories between 20 and 24, 25.0—26.9, 27.0—28.9, 29.0—29.9, 30.0—31.9, 32.0—34.9, 35.0—39.9, and ≥40.0 kg/m2).

Adjusted for all of the above and for waist to hip circumference ratio (continuous). Waist to hip circumference ratio was multiply imputed (n=10 imputations) for approximately 60% of subjects. See text for additional details.

Incident breast cancers were identified by self-report on biennial questionnaires and subsequently confirmed by physician review of medical records. Tumor details (e.g., hormone receptor status, pathology) were extracted from medical records during review. We assembled separate case-control datasets to examine the incidence of combined invasive and in situ disease, invasive disease, ER-positive invasive disease, and ER-negative invasive disease.

Statistical analysis

We tabulated summary statistics for key breast cancer and mammographic density risk factors among breast cancer controls according to quartile of plasma c-peptide concentration. For breast density outcomes, we combined the NHS and NHSII controls (n=1,469). We used general linear models to regress mammographic breast density outcomes on quartile of c-peptide concentration, with and without adjustment for candidate confounders. The distributions of dense, non-dense, and percent dense area were each unimodal and positively skewed. Square-root transformation yielded normal distributions for each of these parameters. We compared linear models using the original and root-transformed density parameters as regressands. WHR data were missing for approximately 20% of women. We therefore multiply imputed WHR (n=10 imputations) using a full Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. We then fit separate models adjusting for WHR and other covariates for each imputed data set and pooled the resulting parameter estimates so that variances reflected additional uncertainty due to imputed WHR values (31). All breast density models were adjusted for batch of mammography reading, which was modeled as a random effect. Density associations were calculated as the difference in least-square mean dense area, non-dense area, or percent dense area between c-peptide quartiles, with respect to the first quartile.

Breast cancer incidence was modeled as the occurrence of any breast cancer (invasive and in situ), only invasive disease, only ER-positive disease, or only ER-negative disease. We modeled associations with these outcomes separately for the NHS and NHSII case-control studies and pooled the results by calculating inverse variance weighted averages of the coefficients. In sub-analyses we combined pre- or postmenopausal women from both cohorts to estimate associations within these strata. We explored the impact of adjustment for plasma free estradiol and SHBG in the NHS cases and controls who were postmenopausal and either former or never-users of PMH at the time of blood collection (260 cases and 459 controls in total; 196 cases and 358 controls with measured estradiol and SHBG). We used conditional and unconditional logistic regression models with and without adjustment for additional candidate confounders to model associations between quartile of c-peptide and breast cancer incidence. We plotted confidence interval functions to evaluate heterogeneity of associations according to menopausal and PMH status at diagnosis and tumor estrogen receptor status (32). Because controls were sampled from cases’ risk sets, the case-control odds ratios approximate breast cancer incidence rate ratios (33). All analyses were carried out in SAS v.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

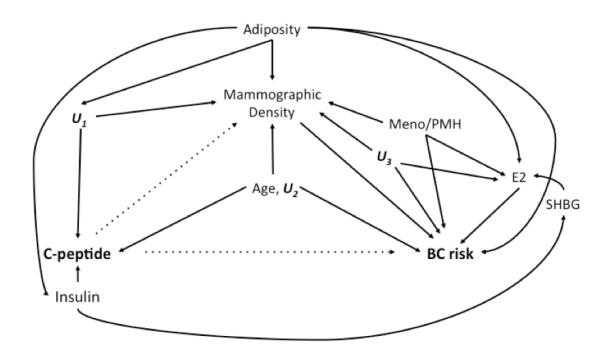

Figure 1 is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) depicting the hypothesized relationships among key analytic variables. We evaluated this DAG to identify minimally sufficient sets of confounders for which to adjust our regression models, and to avoid over- or unnecessary adjustment (34,35). Breast cancer incidence models were not adjusted for breast density measurements since mammographic density occupies a pathway between c-peptide and breast cancer incidence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graph depicting the hypothesized relationship between variables relevant to the estimation of associations between c-peptide levels, mammographic density measurements, and risk of invasive breast carcinoma.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the cohort according to plasma c-peptide concentration

Table 1 shows the distribution of NHS and NHSII breast cancer controls (n=1,785) according to demographic and lifestyle characteristics, within quartiles of plasma c-peptide concentration. Mean age at blood draw was similar across c-peptide quartiles. Among postmenopausal women, never or former users of PMH were more likely than current users to have c-peptide concentrations in the third or fourth quartile. C-peptide was strongly and positively associated with adiposity (both BMI and WHR) and quintile of plasma estradiol, and negatively associated with quintile of plasma SHBG. We saw no appreciable difference across quartiles for parity, age at first birth, age at menarche, smoking status, and alcohol consumption.

Table 1.

Characteristics of breast cancer controls at the time of blood collection, according to quartiles of plasma c-peptide concentration. Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study 2 combined (n=1,785).

| Characteristics | Quartile of plasma c-peptide concentration (ng/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 n=443 |

Q2 n=454 |

Q3 n=445 |

Q4 n=443 |

|

| Age, mean (sd) | 51.4 (8.4) | 51.4 (8.7) | 53.4 (8.7) | 52.6 (8.9) |

|

| ||||

| Menopausal/ PMH status, n (%) | ||||

| Premenopausal | 202 (49) | 218 (50) | 166 (40) | 189 (45) |

| Postmenopausal/ never or past | 96 (23) | 114 (26) | 154 (37) | 156 (37) |

| Postmenopausal/ current | 118 (28) | 101 (23) | 98 (23) | 73 (17) |

| (Missing) | 27 | 21 | 27 | 25 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index, mean (sd) | 22.6 (3.9) | 23.8 (4.3) | 26.1 (5.6) | 28.5 (7.0) |

|

| ||||

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (sd) | 0.76 (0.07) | 0.78 (0.08) | 0.80 (0.08) | 0.82 (0.13) |

| [Missing, n(%)] | 182 (41) | 178 (39) | 194 (44) | 183 (41) |

|

| ||||

| Reproductive history | ||||

| Parous, n (%) | 384 (87) | 404 (90) | 405 (91) | 397 (90) |

| Parity, median (mode) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Age at first birth, mean (sd) | 25.7 (3.6) | 25.5 (3.7) | 25.5 (3.9) | 25.7 (4.0) |

|

| ||||

| Age at menarche, mean (sd) | 12.0 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.3) | 11.9 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.0) |

|

| ||||

| Positive breast cancer history in mother or sister, n (%) |

43 (10) | 60 (13) | 50 (11) | 46 (10) |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol consumption, cumulative average g/day, median (q1, q3) |

2.6 (0.4, 8.6) | 2.6 (0.8, 7.9) | 2.0 (0.5, 6.1) | 1.6 (0.2, 5.7) |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never smoked | 257 (59) | 249 (55) | 225 (51) | 250 (57) |

| Former smoker | 145 (33) | 160 (35) | 173 (39) | 143 (33) |

| Current smoker | 37 (84) | 43 (10) | 44 (10) | 46 (10) |

| (Missing) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|

| ||||

|

Among NHS Postmenopausal

women who were never or past users of PMH at blood draw: |

n=95 | n=95 | n=132 | n=137 |

|

| ||||

| Quintile, plasma estradiol, n (%) | ||||

| Q1 | 18 (28) | 18 (26) | 15 (13) | 9 (8.0) |

| Q2 | 9 (14) | 7 (10) | 14 (12) | 13 (12) |

| Q3 | 25 (39) | 22 (32) | 42 (37) | 23 (20) |

| Q4 | 8 (13) | 14 (21) | 17 (15) | 23 (20) |

| Q5 | 4 (6.3) | 7 (10) | 25 (22) | 45 (40) |

| (Missing) | 31 | 27 | 19 | 24 |

|

| ||||

| Quintile, plasma SHBG, n (%) | ||||

| Q1 | 6 (8.0) | 5 (6.3) | 24 (19) | 48 (40) |

| Q2 | 8 (11) | 13 (16) | 34 (27) | 28 (23) |

| Q3 | 14 (19) | 20 (25) | 22 (18) | 18 (15) |

| Q4 | 14 (19) | 24 (30) | 27 (22) | 15 (12) |

| Q5 | 33 (44) | 17 (22) | 18 (14) | 12 (10) |

| (Missing) | 20 | 16 | 7 | 16 |

SHBG: Sex hormone binding globulin.

C-peptide and mammographic density measurements

Table 2 shows the associations between quartile of c-peptide and breast dense area, non-dense area, and percent dense area. The directions and relative magnitudes of associations were consistent between models using untransformed and root-transformed density parameters. Table 2 therefore reports results from regression of the untransformed variables to facilitate clinically meaningful interpretation. The median time difference between blood draw and mammogram was −5 months (that is, blood draw preceded mammogram by 5 months), with a range from −125 to 70 months.

In analyses adjusted only for age and batch of mammogram reading, c-peptide was positively associated with breast non-dense area (difference in least-square means, Q4 vs. Q1=73cm2, 95% CI: 63, 84), negatively associated with breast dense area (difference in least-square means, Q4 vs. Q1=−7.7cm2, 95% CI: −13, −2.4), and negatively associated with percent dense area (difference in least-square means, Q4 vs. Q1=−14%, 95% CI: −17, −11). Associations were not materially affected after additional adjustment for reproductive factors, menopausal status and use of PMH, and cumulative average daily ethanol consumption (multivariate adjusted difference in least-square means, Q4 vs. Q1; breast non-dense area=72cm2, 95% CI: 61, 83; breast dense area=−9.2cm2, 95% CI: −15, −3.8; percent dense area=−14%, 95% CI: −17, −11). However, further adjustment for adiposity (BMI and WHR) yielded near-null differences for all three breast density outcomes (fully adjusted difference in least-square means, Q4 vs. Q1; breast non-dense area=10cm2, 95% CI: −7.3, 28; breast dense area=1.2cm2, 95% CI: −8.4, 11; percent dense area=−1.5%, 95% CI: −6.4, 3.4). Conclusions were similar within strata of menopausal status at mammogram (Table 2).

C-peptide and breast cancer incidence

Table 3 reports associations between quartile of c-peptide and incident breast cancer. Associations with invasive and in situ disease, only invasive disease, and ER-positive disease were pooled across NHS and NHSII. Women in the highest quartile had a 40% higher incidence of invasive or in situ breast cancer (adjusted OR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.9) compared with women in the lowest quartile. Similar associations were observed for invasive disease alone (adjusted OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.1, 2.0), and for ER-positive disease (adjusted OR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.0).

Table 3.

Association between quartile of plasma c-peptide concentration and risk of breast cancer. Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II. Associations are relative to the first quartile (i.e., Q1).

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

|

Cases/ controls |

Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Nurses’ Health Study | ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Conditional2 OR (95% CI) Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

762/ 1,146 | 1.2 (0.87, 1.5) 1.1 (0.84, 1.5) |

1.2 (0.91, 1.6) 1.3 (0.93, 1.7) |

1.4 (1.1, 1.9) 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) |

|

| ||||

| Invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

636/ 1,146 | 1.1 (0.82, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.85, 1.6) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) |

|

| ||||

| ER(+) invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

438/ 1,146 | 1.1 (0.77, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.76, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) |

| ER(−) invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

122/ 1,146 | 1.1 (0.57, 2.0) | 1.7 (0.91, 3.1) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.2) |

|

| ||||

| Postmenopausal women, no PMH | ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) Adjusted (not for BMI)3 OR (95% CI) E2-adjusted4,5 OR (95 % CI) E2- and SHBG-adjusted4-6 OR (95% CI) |

260/ 459 | 1.2 (0.73, 2.1) 1.3 (0.80, 2.2) 1.3 (0.70, 2.6) 1.4 (0.72, 2.7) |

0.93 (0.55, 1.6) 1.0 (0.61, 1.6) 0.91 (0.49, 1.7) 1.0 (0.54, 2.0) |

1.5 (0.90, 2.6) 1.7 (1.0, 2.7) 1.5 (0.77, 2.8) 1.6 (0.81, 3.1) |

|

| ||||

| Postmenopausal women, current users of PMH |

||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

237/ 318 | 1.2 (0.76, 2.0) | 1.2 (0.69, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.3) |

|

| ||||

| Nurses’ Health Study II | ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Conditional2 OR (95% CI) Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

322/ 639 | 1.1 (0.75, 1.6) 1.1 (0.74, 1.7) |

1.1 (0.76, 1.7) 1.2 (0.77, 1.9) |

1.0 (0.68, 1.5) 1.1 (0.66, 1.8) |

|

| ||||

| Invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

230/ 639 | 1.0 (0.62, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.73, 2.0) | 1.1 (0.65, 2.0) |

|

| ||||

| ER(+) invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

200/ 639 | 1.1 (0.68, 1.9) | 1.1 (0.62, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.64, 2.1) |

|

| ||||

| Pooled (NHS and NHSII) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Conditional2 OR (95% CI) Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

1,084/ 1,785 | 1.1 (0.91, 1.4) 1.1 (0.88, 1.4) |

1.2 (0.94, 1.5) 1.2 (0.97, 1.6) |

1.3 (1.0, 1.6) 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) |

|

| ||||

| Invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

866/ 1,785 | 1.1 (0.84, 1.4) | 1.2 (0.91, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

|

| ||||

| ER(+) invasive breast cancer, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

638/ 1,785 | 1.1 (0.83, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.80, 1.5) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) |

|

| ||||

| ER(−) invasive breast cancer*, Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

173/ 1,785 | 1.1 (0.62, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) | 2.0 (1.2, 3.6) |

|

| ||||

| Premenopausal women 1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Conditional2 OR (95% CI) Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

187/ 519 | 1.0 (0.59, 1.8) 0.81 (0.49, 1.3) |

1.7 (1.0, 2.9) 1.5 (0.88, 2.5) |

1.7 (0.93, 3.1) 1.4 (0.79, 2.5) |

|

| ||||

| Postmenopausal women 1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Invasive and in situ breast cancer, Conditional2 OR (95% CI) Adjusted4 OR (95% CI) |

796/ 1,086 | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) |

1.2 (0.89, 1.7) 1.2 (0.88, 1.6) |

1.5 (1.1, 2.1) 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

ER-negative associations were not estimable in the NHSII case-control study; rather than pooling, these estimates are derived from combining NHS and NHSII ER-negative cases and controls.

Combining premenopausal or postmenopausal subjects (at time of diagnosis) across NHS and NHSII.

Models conditioned on matching factors, defined at time of blood draw: age (±1 year), menopausal status (premenopausal/unknown or postmenopausal), use of PMH (current or never/former), fasting status at blood collection (≥8 hours or <8 hours), and date/time of day of blood collection (±1 month, ±2 hours).

Models adjusted for matching factors and further adjusted for cumulative average daily alcohol consumption at blood draw (design variables: nondrinker, 0.1 to 4.9, 5.0 to 9.9, 10.0 to 19.9, and ≥20 g/day), age at first birth (continuous), age at menarche (continuous), and history of breast cancer diagnosed in mother or sister.

Models adjusted for matching factors and further adjusted for body mass index at blood draw (13 design variables, as listed in Table 2 footnote), cumulative average daily ethanol consumption at blood draw (design variables: nondrinker, 0.1 to 4.9, 5.0 to 9.9, 10.0 to 19.9, and ≥20 g/day), age at first birth (continuous), age at menarche (continuous), and history of breast cancer diagnosed in mother or sister.

Model additionally adjusted for quintile of free plasma estradiol level at time of blood collection (design variables).

Model additionally adjusted for quartile of plasma sex hormone biding globulin at time of blood collection (design variables).

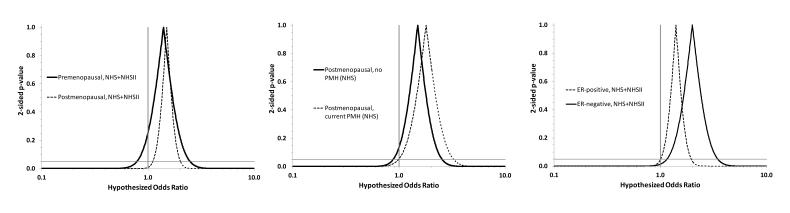

The association between c-peptide and ER-negative disease was estimable only in the NHS population (the NHSII data set had only 51 ER-negative cases), and showed a 120% increase in the rate of ER-negative disease comparing the top and bottom quartiles (adjusted OR=2.2, 95% CI: 1.2, 4.2). Analyses based on combining the ER-negative cases and matched controls from NHS and NHSII continued to show a stronger association for ER-negative disease (top vs. bottom quartile: adjusted OR=2.0, 95% CI: 1.2, 3.6). Associations were similar for breast cancers diagnosed before and after menopause (Figure 2 left panel; premenopausal, top vs. bottom quartile: adjusted OR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.79, 2.5; postmenopausal, top vs. bottom quartile: adjusted OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.1, 2.0).

Figure 2.

Confidence interval functions depicting heterogeneity of associations between c-peptide level and breast cancer incidence (4th quartile compared with the 1st quartile) according to menopausal status at breast cancer diagnosis, hormone therapy (PMH) status, and estrogen receptor status of the primary tumor

Without free estradiol adjustment, c-peptide was associated with a 50% increase in the rate of invasive and in situ breast cancer incidence among postmenopausal women not currently taking hormones (top vs. bottom quartile: adjusted OR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.90, 2.6). Serial addition to the model of plasma free estradiol and SHBG left this association materially unchanged (Q4 vs. Q1; estradiol-adjusted OR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.77, 2.8; estradiol and SHBG-adjusted OR=1.6, 95% CI: 0.81, 3.1). Results from the estradiol and SHBG-adjusted model were similar when BMI was removed from the vector of covariates (data not shown). The association among current users of PMH was similar to that among nonusers (Figure 2 center panel; current PMH users, top vs. bottom quartile: adjusted OR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.0, 3.3).

Discussion

Plasma c-peptide level was not associated with breast dense area, non-dense area, or percent dense area after adjustment for age and adiposity (BMI and WHR). Null associations remained after further adjustment for demographic, environmental, and reproductive risk factors. We observed a positive association between plasma c-peptide level and breast cancer incidence that persisted under more specific definitions of breast cancer which isolated invasive from in situ disease and which classified invasive tumors by ER status. We noted a somewhat stronger association between c-peptide and ER-negative breast cancer than between c-peptide and ER-positive breast cancer (Figure 2 right panel). Associations were similar according to menopausal status and PMH use at the time of breast cancer diagnosis (Figure 2, left and center panels).

There are two chief hypotheses for why elevated insulin/c-peptide levels might lead to increased breast cancer risk. The first of these posits a direct effect of insulin on breast cancer cell growth by potentiation of the insulin receptor (36), and the second posits an indirect effect of insulin on breast cancer cell growth by increasing the concentration of bioavailable sex hormones. Under the latter hypothesis, high insulin levels decrease expression of SHBG, leading to an increased concentration of free estradiol in the circulation (1,37), which would in turn drive the growth of estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells. Because adjustment for plasma levels of both free estradiol and SHBG did not fundamentally alter the association between c-peptide and breast cancer incidence, and because we observed a somewhat stronger association with ER-negative than with ER-positive disease, our results suggest that the putative causal effect of insulin/c-peptide on breast cancer promotion is exerted chiefly through non-estrogenic pathways. Null associations between insulin/c-peptide and breast density measures suggest that the breast cancer association is not a consequence of an insulin effect on breast density.

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this study are its use of high-quality exposure, covariate, and outcome data. Plasma samples from breast cancer cases and controls were assayed together in discrete batches for c-peptide, estradiol, and SHBG, and laboratory personnel were blinded to outcome status. Assay variation was addressed by calculating batch-specific quantiles, which served as the exposure categories in our analyses. Similarly, mammogram batch variation was addressed with a random effect batch variable in linear models of breast dense, non-dense, and percent dense area. Detailed lifestyle, demographic, and dietary data were available within both cohorts, so we were able to account in detail for the confounding effects of adiposity, reproductive factors, and lifestyle exposures (e.g., alcohol consumption) on the measured associations. Breast cancer incidence data were assessed prospectively with respect to blood collection, and specific subtypes of disease were verified by physician review of medical records for 98% of the cases.

Several limitations qualify our findings. Collected mammograms were performed close to the dates of blood draws, so the associations between c-peptide and breast density outcomes are cross-sectional. The null associations we observed may therefore have resulted from a failure to measure c-peptide at an etiologically relevant time with respect to effects on breast density. However, the 3-year intra-class correlation coefficient for plasma c-peptide was 0.58 in an analyte stability study (personal communication from Dr. Jing Ma, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA), which indicates relative stability of this biomarker over time. So our cross-sectional measurement of c-peptide likely represents the level of the biomarker at earlier times, when exposure is more likely to causally affect the outcome. Residual confounding could bias our breast cancer incidence associations. Adiposity is strongly associated with c-peptide level and modestly associated with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (38), and thus has the potential to explain our positive incidence associations. However, we were able to adjust carefully for adiposity using 13 finely divided categories of BMI, and additional adjustment for WHR did not further attenuate risk associations (data not shown). Together these points argue against substantial residual confounding by adiposity.

C-peptide was used as a proxy measurement for insulin, inherently causing misclassification of our primary exposure. Such misclassification is likely unrelated to breast cancer risk and probably cannot account for the positive associations we observed. However, c-peptide itself is a bioactive molecule (39,40), and while no currently understood downstream effect of c-peptide is linked to breast density and breast cancer risk, any attribution of our associations to insulin should be made with this qualification in mind.

Assessment of the impact of estradiol and SHBG levels on the c-peptide and breast cancer associations was hampered by a small number of cases and controls with data on all three of these plasma markers, however the main association between c-peptide and breast cancer risk among those with measured estradiol and SHBG was similar to the association in the total study population. These results also apply only to postmenopausal women who were not current users of PMH. Finally, it is possible that some or all of the observed association between c-peptide/insulin and breast cancer risk is due to confounding by a common cause of hyperinsulinemia and breast tumor promotion, for example genetic modification of signaling through the PTEN/PI3K pathway (41). In the absence of such a common cause, our results suggest that the association arises from a direct stimulating effect of insulin on breast cancer cell growth.

The current body of literature on the insulin/breast cancer association is rather heterogeneous, with reported associations ranging from negative to positive and in some cases being modified by menopausal status, use of hormone therapy, or tumor hormone receptor status (3-20). Our findings generally comport with those from most other prospective investigations (6,10,11,16,19,20). The largest of these, Verheus et al (19) and Gunter et al (10), reported positive associations between c-peptide and breast cancer risk that were not substantially affected by estradiol adjustment (10,19). However, the positive association in the Verheus study was apparent only for women older than age 60, and neither the Verheus or Gunter studies evaluated risk heterogeneity by ER status. An earlier study nested in NHSII reported a positive association only for ER+/PR+ disease, and the overall association strengthened upon adjustment for plasma estradiol (18). In the present study, ER-negative associations were similar when events were sub-classified by PR status (data not shown). Therefore, this discrepancy may be due to a stabilization of estimates owing to an increased number of breast cancer cases in the NHSII population since publication of the original report (18). Only two other studies have evaluated risk heterogeneity by ER status; Cust et al observed no heterogeneity (20), while Hirose et al observed a positive association only between c-peptide and ER-negative disease (7).

In conclusion, we observed a positive association between c-peptide, a proxy measurement of insulin secretion, and risk of breast cancer in pre- and postmenopausal women. We saw no evidence for an association between c-peptide and breast dense area, non-dense area, and percent dense area independent of adiposity. Our risk associations were stronger for ER-negative disease, and not attenuated by adjustment for free estradiol and SHBG. These observations suggest that the association between insulin and breast cancer risk is not a consequence of increased sex hormone concentrations nor of induced changes in breast density.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 CA49449, R01 CA67262, P01 CA87969, R01 CA50385, R01 CA124865, R01 CA131332, and T32 CA009001. We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY.

Abbrev.

- CV

Coefficient of variation

- DAG

Directed acyclic graph

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- NHSII

Nurses’ Health Study II

- PMH

Postmenopausal hormones

- SHBG

Sex hormone binding globulin

- WHR

Waist to hip circumference ratio

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No author declares a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Singh A, Hamilton-Fairley D, Koistinen R, Seppälä M, James VH, Franks S, et al. Effect of insulin-like growth factor-type I (IGF-I) and insulin on the secretion of sex hormone binding globulin and IGF-I binding protein (IBP-I) by human hepatoma cells. J Endocrinol. 1990;124:R1–3. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.124r001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faber OK, Binder C. C-peptide: an index of insulin secretion. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1986;2:331–45. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruning PF, Bonfrèr JM, van Noord PA, Hart AA, de Jong-Bakker M, Nooijen WJ. Insulin resistance and breast-cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:511–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Giudice ME, Fantus IG, Ezzat S, McKeown-Eyssen G, Page D, Goodwin PJ. Insulin and related factors in premenopausal breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;47:111–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1005831013718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang G, Lu G, Jin F, Dai Q, Best R, Shu XO, et al. Population-based, case-control study of blood C-peptide level and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muti P, Quattrin T, Grant BJB, Krogh V, Micheli A, Schünemann HJ, et al. Fasting glucose is a risk factor for breast cancer: a prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1361–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirose K, Toyama T, Iwata H, Takezaki T, Hamajima N, Tajima K. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I and breast cancer risk in Japanese women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2003;4:239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schairer C, Hill D, Sturgeon SR, Fears T, Pollak M, Mies C, et al. Serum concentrations of IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and c-peptide and risk of hyperplasia and cancer of the breast in postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:773–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malin A, Dai Q, Yu H, Shu X-O, Jin F, Gao Y-T, et al. Evaluation of the synergistic effect of insulin resistance and insulin-like growth factors on the risk of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:694–700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, Manson JE, et al. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:48–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabat GC, Kim M, Caan BJ, Chlebowski RT, Gunter MJ, Ho GYF, et al. Repeated measures of serum glucose and insulin in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2704–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jernström H, Barrett-Connor E. Obesity, weight change, fasting insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels in women with and without breast cancer: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:1265–72. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toniolo P, Bruning PF, Akhmedkhanov A, Bonfrèr JM, Koenig KL, Lukanova A, et al. Serum insulin-like growth factor-I and breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:828–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001201)88:5<828::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaaks R, Lundin E, Rinaldi S, Manjer J, Biessy C, Söderberg S, et al. Prospective study of IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins, and breast cancer risk, in northern and southern Sweden. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:307–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1015270324325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mink PJ, Shahar E, Rosamond WD, Alberg AJ, Folsom AR. Serum insulin and glucose levels and breast cancer incidence: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:349–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keinan-Boker L, Bueno De Mesquita HB, Kaaks R, van Gils CH, Van Noord PAH, Rinaldi S, et al. Circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor I, its binding proteins -1,-2, -3, C-peptide and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:90–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falk RT, Brinton LA, Madigan MP, Potischman N, Sturgeon SR, Malone KE, et al. Interrelationships between serum leptin, IGF-1, IGFBP3, C-peptide and prolactin and breast cancer risk in young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98:157–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliassen AH, Tworoger SS, Mantzoros CS, Pollak MN, Hankinson SE. Circulating insulin and c-peptide levels and risk of breast cancer among predominately premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:161–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verheus M, Peeters PHM, Rinaldi S, Dossus L, Biessy C, Olsen A, et al. Serum C-peptide levels and breast cancer risk: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Int J Cancer. 2006;119:659–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cust AE, Stocks T, Lukanova A, Lundin E, Hallmans G, Kaaks R, et al. The influence of overweight and insulin resistance on breast cancer risk and tumour stage at diagnosis: a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:567–76. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisani P. Hyper-insulinaemia and cancer, meta-analyses of epidemiological studies. Vol. 114. Informa UK Ltd; UK: 2008. pp. 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd N, Martin L, Bronskill M, Yaffe M, Duric N, Minkin S. Breast tissue composition and susceptibility to breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 102:1224–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersson A, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Tamimi RM. Nondense mammographic area and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R100. doi: 10.1186/bcr3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokate M, Peeters PHM, Peelen LM, Haars G, Veldhuis WB, van Gils CH. Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: the role of the fat surrounding the fibroglandular tissue. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R103. doi: 10.1186/bcr3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolin KY, Colangelo LA, Chiu BC-H, Ainsworth B, Chatterton R, Gapstur SM. Associations of Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Insulin with Percent Breast Density in Hispanic Women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:1004–11. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diorio C, Pollak M, Byrne C, Mâsse B, Hébert-Croteau N, Yaffe M, et al. Levels of C-peptide and mammographic breast density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2661–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:388–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hankinson S, Willett W. Alcohol, height, and adiposity in relation to estrogen and prolactin levels in postmenopausal women. Journal of the …. 1995 doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.17.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Plasma sex steroid hormone levels and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1292–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.17.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99:1178–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SAS, Inc. The MIANALYZE Procedure. 2007. SAS OnlineDoc 9.1.3. 2002.

- 32.Sullivan K, Foster D. Use of the confidence interval function. Epidemiology. 1990;1:39–42. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland S. Interpretation and choice of effect measures in epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:761–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins J. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20:488–95. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maggio M, Lauretani F, Basaria S, Ceda GP, Bandinelli S, Metter EJ, et al. Sex hormone binding globulin levels across the adult lifespan in women--the role of body mass index and fasting insulin. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2008;31:597–601. doi: 10.1007/BF03345608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, Chlebowski RT, Hays J, Kuller L, et al. Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:741–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1020239211145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hills CE, Brunskill NJ. C-Peptide and its intracellular signaling. Rev Diabet Stud. 2009;6:138–47. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2009.6.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hills CE, Brunskill NJ. Intracellular signalling by C-peptide. Exp Diabetes Res. 2008;2008:635158. doi: 10.1155/2008/635158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith U. PTEN--linking metabolism, cell growth, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1061–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1208934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]