Abstract

Objective

To describe the history and evolution of the collaborative depression care model and new research aimed at enhancing dissemination.

Method

Four keynote speakers from the 2009 NIMH Annual Mental Health Services Meeting collaborated in this article in order to describe the history and evolution of collaborative depression care, adaptation of collaborative care to new populations and medical settings, and optimal ways to enhance dissemination of this model.

Results

Extensive evidence across 37 randomized trials has shown the effectiveness of collaborative care vs. usual primary care in enhancing quality of depression care and in improving depressive outcomes for up to 2 to 5 years. Collaborative care is currently being disseminated in large health care organizations such as the Veterans Administration and Kaiser Permanente, as well as in fee-for-services systems and federally funded clinic systems of care in multiple states. New adaptations of collaborative care are being tested in pediatric and ob-gyn populations as well as in populations of patients with multiple comorbid medical illnesses. New NIMH-funded research is also testing community-based participatory research approaches to collaborative care to attempt to decrease disparities of care in underserved minority populations.

Conclusion

Collaborative depression care has extensive research supporting the effectiveness of this model. New research and demonstration projects have focused on adapting this model to new populations and medical settings and on studying ways to optimally disseminate this approach to care, including developing financial models to incentivize dissemination and partnerships with community populations to enhance sustainability and to decrease disparities in quality of mental health care.

Keywords: Collaborative depression care, Dissemination, Sustainability

Over the last three decades, tremendous progress has been made by mental health services researchers in improving recognition and quality of treatment for patients with affective disorders within primary care systems. In the United States, this research was initially stimulated by the findings from the Epidemiology Catchment Area Study that showed that over half of the community respondents in the United States with depressive and anxiety disorders were treated exclusively in primary care settings [1]. This finding led Regier et al. [1] to label the primary care system the “de facto” mental health care system of the United States.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, health services researchers documented that 5% to 12% of primary care patients met DSM-IV criteria for major depression [2]. Patients with major depression in primary care systems were also shown to have high numbers of medically unexplained symptoms [3], a greater degree of comorbid medical illness [4], as much or more functional impairment as patients with other common medical disorders such as diabetes or heart disease [5], and up to twofold higher medical utilization and costs [6,7].

Researchers in the 1980s and 1990s also documented the gaps in quality of depression care in primary care systems. Studies showed that only 25% to 50% of patients with depression were accurately diagnosed by primary care physicians and, among those who were accurately diagnosed, few received adequate dosage and duration of either pharmacotherapy or evidence-based depression psychotherapy [8,9]. Naturalistic primary care-based studies found that approximately 40% of patients discontinued antidepressants in the first 4–6 weeks of treatment [10]. This was largely because the frequency of follow-up in primary care clinics was quite limited: the median performance of 247 health plans on the HEDIS depression performance criteria that recommended that patients initiating treatment with an antidepressant have three follow-up visits in the first 90 days has been only 20% for over a decade [11]. Even when close follow-up occurs, treatment is often not adjusted according to need, based on severity of residual symptoms [12]. Large-scale studies have also shown that approximately 40% to 50% of patients with depression referred by primary care doctors to mental health specialists fail to complete the referral [13]. The result is that only approximately 40% of primary care patients with depression who were accurately diagnosed recovered over a 4- to 6-month period [14]. These gaps in treatment were documented to be even more problematic in minority populations and in those living below US poverty levels [15].

Early research attempts to improve quality of care and outcomes of patients with depression and anxiety in primary care tested whether providing physicians with evidence of depression based on depression rating scales would increase detection, provision of evidence-based treatment and enhanced outcomes. These studies randomized patients screening as depressed into two groups: patients whose physicians were notified of their depression status vs. those in whom physician notification did not occur. These studies showed that physician notification of depression status resulted in slight improvements in quality of depression care, but no replicable effects on improved depression outcomes [16]. Several later studies built on these initial failures to attempt to enhance depression outcomes by randomizing depressed primary care patients into those whose physicians were notified about a major depression diagnosis and provided with an algorithm of recommended depression care vs. those allowed to remain in usual care [17,18]. Again, no replicable effects on patient-level outcomes were demonstrated.

From 1990 to 1996, NIMH with help from AHRQ funded nine depression collaborative care trials [19]. These trials were developed during the same era in which Wagner et al. [20,21] at Group Health in Seattle described four key elements of the organization of care that must be implemented to improve outcomes of populations of patients with chronic illness: the delivery system must be designed so that each patient's care includes proactive follow-up visits or telephone contacts, adherence monitoring and response to treatment assessments; information systems must be established to support the use of disease registries to track provision of care according to guideline and individual treatment plans; self-management training and support must be provided to patients and key family members so that they are equipped with the information and skills required to effectively manage their illness in order to develop an active partnership with the health care team; and decision support must be provided to primary care physicians, including facile access to guidelines, expert systems and specialty consultation within the context of a structured care program. Wagner et al. [20,21] emphasized that these organizational changes in practice usually required a team approach with an allied health professional such as a nurse providing the close monitoring and frequent contacts.

The key components of collaborative depression care developed for these initial federally funded trials included many of the key components of Wagner et al. [20,21], such as enhanced patient education with pamphlets, books and videotapes; use of either allied health professionals such as nurses or mental health professionals to provide closer follow-up to track outcomes, side-effects and adherence to treatment; use of a tool such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to track outcomes, and development of an electronic depression register to facilitate caseload supervision; a psychiatrist to provide caseload supervision of depression care managers and recommendations about changes in antidepressant medication; and stepped-care approaches that provided incremental increases in treatment for patients with persistent symptoms [22]. In some of these trials, depression case managers could also provide an option of brief evidence-based psychotherapy [22]. These collaborative care approaches enhanced the systematization and organization of primary care practice to provide closer follow-up; patient education and monitoring of symptoms, side-effects and adherence; and integrated specialty knowledge about antidepressant medication into primary care practice.

A recent meta-analysis reviewed 37 trials of depression collaborative care and found evidence compared to usual primary care of twofold higher rates of adherence to antidepressant medication over the first 6 months of treatment and improved depressive outcomes that often persisted for at least 2 years [23]. Six new trials have also tested collaborative care approaches to treating depression in patients with a chronic medical illness (diabetes, cancer, stroke and post-coronary bypass grafting surgery) and found significant improvements in quality of care and depressive outcomes compared to usual care [24–29]. Cost-effectiveness analyses demonstrated that total ambulatory costs associated with collaborative care increased approximately $125 to $600, but with significant and substantial gains in depression-free days over a 1- to 2-year period [23,30]. In some studies of more complex depressed patients, including those with major depression and diabetes [31,32], panic disorder and major depression [33,34], and those with ≥4 DSM-IV symptoms of major depression 8 weeks after the primary care doctor-initiated antidepressant treatment [35], there was evidence of a high probability of savings in total medical costs associated with collaborative care.

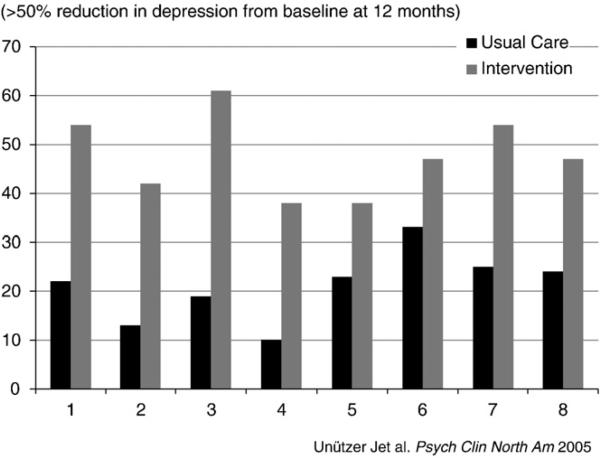

A key problem in the US health care system is that minority populations and people living below US poverty levels have been shown to have marked disparities in access to quality mental health care [15]. Several of the larger multisite collaborative care studies examined whether the benefits of this care model were found in populations living below US poverty levels and in minority patients. A recurrent finding from these trials has been that patients living below poverty levels and patients from ethnic minority groups have experienced equal or even greater benefits from collaborative care vs. usual care as Caucasian or more middle-class populations [25,36–38]. Fig. 1 shows data from the eight sites involved in the IMPACT trial that randomized 1801 adults age 60 and older from eight health care organizations in five states of the USA. Study sites with high proportions of ethnic minority participants (African Americans and Latinos) had similar or greater incremental collaborative vs. usual care differences in depression outcomes as sites serving largely whites [29]. More recent studies in which the collaborative care programs for depression were tested in primarily low-income ethnic minority groups confirm the relative effectiveness of this approach [25,26,39,40].

Fig. 1.

IMPACT: Depression outcomes are robust across eight diverse clinics and populations.

1. New collaborative care research initiatives

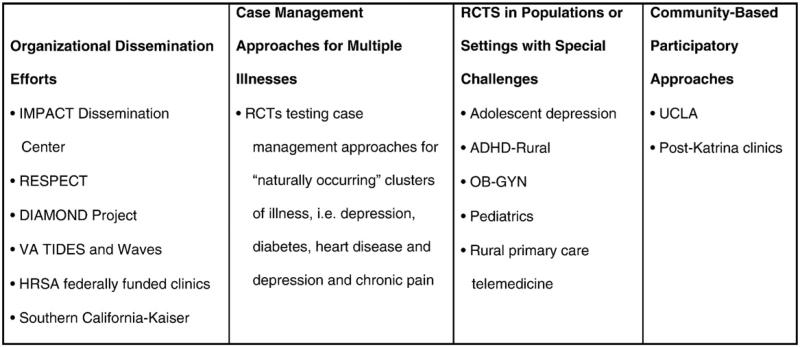

Fig. 2 describes four initiatives that are extending primary care research on collaborative care, including organized dissemination efforts to integrate collaborative care into large systems of care such as the Veterans Affairs (VA) system as well as primary care clinics throughout the state of Minnesota [the DIAMOND (Depression Improvement Across Minnesota: Offering a New Direction) project]; care management approaches for patients with depression and other medical illnesses that attempt to improve quality of care and outcomes for both comorbid medical illnesses and depression; randomized trials testing collaborative management in new settings (such as obstetrics and gynecology and pediatric settings) and populations (such as adolescents with depression and children living in rural areas with ADHD); and community-based participatory approaches to building enhanced depression care programs.

Fig. 2.

New efforts to enhance dissemination of collaborative care.

1.1. Organized dissemination efforts

Although the research evidence for collaborative depression care is robust and comprehensive [23], it can be a great deal more challenging to implement such programs in the real world than to conduct the research to establish the evidence base for such programs. Implementers need more than peer-reviewed publications in major medical journals. They need predictable ways to cover program startup and operational costs, tools such as job descriptions and disease management registries, and implementation support that helps their practices develop the necessary changes in roles to integrate such programs into usual primary care. Several regional and national efforts have developed over the past few years to support such implementation funded by regional purchasing and quality improvement collaboratives (e.g., the Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative [41] and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) [42]), foundations (e.g., McArthur Foundation [43], Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [44], California Endowment [45], Hogg Foundation for Mental Health [46] and John A. Hartford Foundation [47]) and large health care organizations (e.g., the Veterans Administration). These efforts have been collecting valuable information on optimum methods to move collaborative care from science to practice. For example, the IMPACT coordinating center funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation at the University of Washington has trained over 3500 clinicians in over 200 practices around the country in the IMPACT program [47,48]. The next sections briefly profile three examples of large-scale implementation of collaborative care.

After a decade of research on improving depression in primary care in the VA health care system [49–54], the VA has developed a robust effort to support the implementation of evidence-based collaborative care for depression throughout its facilities nationwide [55]. A national QUERI approach has developed systematic approaches to disseminating and implementing evidence-based approaches [56,57] and a national office was funded to support these efforts [55]. Over the past 2 years, VA leadership has supported the addition of several hundred staff to help implement collaborative care for depression in primary care clinics throughout the VA health care system nationally and funded VA researchers to study this dissemination process [51–55].

Other large health care systems have also moved from research to the widespread implementation of evidence-based collaborative care. Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC), a health plan that provides health care to over 3 million individuals in Southern California, participated as a study site in the IMPACT trial from 1999 to 2003. After completing the trial, leadership at San Diego KPSC continued the program in place without grant funding and KPSC conducted a study of a slightly adapted version of the IMPACT program. This study showed the program to be as effective as the intervention tested in the original IMPACT study and associated with lower overall health care costs [58]. Long-term confirmation of cost savings related to the IMPACT program [59] further strengthened the argument for widespread implementation of the program, particularly in high-risk (medically ill) patients. Collaborative care for depression has been incorporated into care management programs for cardiovascular and other chronic medical disorders in 11 of 12 regional medical centers and is now available to millions of KPSC members in Southern California [60].

Large-scale implementation of evidence-based collaborative care programs has been somewhat more successful in large capitated health care organizations such as the VA or Kaiser Permanente. In smaller clinics that bill a large number of insurance companies in a fee-for-service model, adaptation of such programs has been more challenging. One important example of how to accomplish such large-scale implementation in largely fee-for-service models is the DIAMOND program in Minnesota [42]. In this example, ICSI, a quality improvement organization chartered by health plans in the state of Minnesota, has led a collaboration of nine health plans and 25 medical groups to implement an evidence-based collaborative care program for depression based on the IMPACT model in over 85 clinics in Minnesota. ICSI supports five sequences of clinics entering the program, training and certifying staff in evidence-based depression care and facilitating ongoing program implementation and evaluation. Clinics are paid by health plans using a case rate that covers evidence-based collaborative care (care management and psychiatric caseload supervision and consultation) in addition to traditional fee-for-service billing by the patients’ regular primary care providers. This unique payment mechanism allows even moderate-sized primary care clinics to designate and train staff and implement such evidence-based programs. Early findings reported by ICSI [61] indicate that, at 6 months, response and remission rates achieved in the first 10 implementing clinics are as good as or better than rates found in the original IMPACT trial. The DIAMOND experience is creating important experience and knowledge in diverse real-world settings that may help inform similar implementation efforts and that may become an exemplary model for developing medical home programs in primary care. An NIMH-funded study using a novel quasi experimental design is evaluating the implementation of this state-wide program.

These early implementation experiences suggest that to successfully help “translate” the knowledge about collaborative care for depression into diverse practice settings will require an intense and persistent commitment of local and national leaders to overcome barriers to implementation of these evidence-based programs, and substantial implementation support to help create and support collaborative care teams that not only are structurally or physically integrated but that have truly shared clinical workflows, shared accountability for program effectiveness and client outcomes, and, perhaps most importantly, financing mechanisms to initiate and sustain such programs under diverse payment systems [62]. Federal and state agencies and funders such as the NIMH, AHRQ, HRSA, SAMHSA and CMS should work together to study optimum ways to disseminate collaborative care and funding to develop mechanisms that facilitate and encourage the implementation of such evidence-based programs in diverse health care systems.

2. Combined case management approaches for depression and comorbid medical illnesses

Despite evidence that collaborative care teams that are integrated into primary care improve the quality of care and outcomes of chronic illnesses like depression, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, most systems of care have struggled with how to pay for these quality-of-care improvements. Since it will be difficult to develop team approaches for each chronic illness and the most costly and time-consuming patients often have depression and other medical comorbidities [63], trials of collaborative care have been recently developed for patients with “natural clusters” of illnesses. These natural clusters can be defined as illnesses that tend to co-occur, maladaptively affect each other's course and for which there are often overlapping guideline recommendations. The importance of developing models of care for patients with these natural clusters of illness is emphasized by recent Medicare data showing that few beneficiaries suffer from only one chronic illness. Among Medicare beneficiaries, fewer than 4% of those with congestive hear failure, depression or diabetes have no other chronic conditions and most (80%, 71% and 56%, respectively) have four or more chronic conditions [64]. However, few quality improvement programs have been tested in patients with multiple chronic illnesses.

One NIMH-funded project, the TEAMcare study, is testing collaborative care for patients with poorly controlled diabetes and/or heart disease (i.e., HbA1c ≥8.5%, LDL>130 or systolic blood pressure >140) who have comorbid major depression and/or dysthymia [65]. The guideline recommendations for diabetes and heart disease overlap for blood pressure and lipid control and use of aspirin and beta blockers for those who have had a myocardial infarction [66,67], and depression occurs in up to 20% of these populations [63]. Depression has been shown to maladaptively affect self-care for these illnesses and is associated with poor medical outcomes [63]. In turn, medical complications from diabetes and heart disease can provoke or worsen depressive episodes [68]. The nurse collaborative care intervention that is being tested in the TEAMcare study will attempt to improve medication management of depression, blood pressure, glycemic and lipid control, as well as improve self-care (adherence to diet, exercise and smoking cessation).

Two federally funded trials have also successfully tested nurse care management recommendations for patients with depression and chronic pain and showed significant effects compared to usual primary care in improving depression, pain and functional outcomes [69,70]. These trials are important because chronic musculoskeletal pain is a very common comorbid condition in those with depression [71], and pain and depression often have bidirectional adverse effects [71].

3. New populations and settings

In contrast to the 37 trials of collaborative care tested in adult populations with depression, there is only one trial testing collaborative care in child/adolescent settings [72]. NIMH has recently funded the second trial of collaborative care vs. usual primary care for adolescents with major depression and also funded the first trial of a telemedicine adaptation of collaborative care for rural children with ADHD. These are important trials given the high prevalence of depression [73] and ADHD [74] in youth, the fact that most youth with depression and ADHD are treated exclusively in pediatric settings, the marked gaps in quality of mental health care for these common psychiatric problems [75,76] and that there is a large workforce shortage for child mental health practitioners, especially in rural settings.

Approximately one-third of all visits for women ages 18 to 24 and the majority of nonillness visits for women under 65 are provided by ob-gyn practitioners [77], and studies have demonstrated even larger gaps in recognition and treatment of depression in ob-gyn compared to other primary care settings [78,79]. Most ob-gyn practitioners receive less training in diagnosing and treating depression, but often are the only physicians whom women seek care from for many of their medical problems as well as pregnancy and hormonal-related issues. NIMH has recently funded a trial of collaborative care for women with depression across the adult age span utilizing two large ob-gyn practices as well as a second study testing an adaptation of collaborative care for pregnant women screened for depression and other psychosocial problems by social workers from the Washington State Medicaid system. This latter study will enroll over 200 pregnant women with depression living below US poverty levels who are receiving benefits from a state Medicaid system.

3.1. Community engagement for collaborative care implementation in mental health

Implementing collaborative care at the community level in underserved communities of color raises the issue of the role of community engagement in planning, use and evaluation of collaborative care, particularly for health conditions such as depression that are subject to social stigma.

Community engagement refers to efforts to involve community agencies and members in leadership regarding the issues and technologies underlying an initiative, such as collaborative care for depression [80]. Community engagement follows a set of principles including promotion of respectful dialogue, development of trust, and honoring equal voice and power of all stakeholders across all phases of the initiative. The central process to achieve community engagement is knowledge exchange with an emphasis on facilitating mutual gain among stakeholders.

Approaches to implementing collaborative care in underserved communities following an approach referred to as community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) have been recently developed [80–82]. CPPR emphasizes co-equal partnership in all phases of research development, implementation, analysis, product development, and dissemination. A CPPR initiative is implemented in stages, including (1) planning and development of goals, framework and specific action plans; (2) implementation and evaluation of action plans; and (3) products, celebration of accomplishments, dissemination and planning for next steps. Each stage follows the engagement principles referred to above to develop a sustainable partnership that builds community capacity for planning and improvement while building partnered evaluation capacity to inform scientific and policy stakeholders [83]. CPPR initiatives are developed through a leadership council and a set of working groups that achieve community input and accountability through hosting forums and promoting dialogue. In this way, a CPPR initiative has core leadership partners, resident experts (academic and community) in working groups, and the broader community engaged in work across stages.

The application of CPPR to implementing collaborative care for depression began with the Witness for Wellness initiative, which sought to initiate a dialogue concerning depression and improvement of services in South Los Angeles [84]. A council guided the initiative, hosted conferences and supported workshops to address stigma, improve services access and quality, and inform policy and advocate for vulnerable populations. Each working group developed and implemented action plans, ranging from arts events to generate community dialogue about depression [85,86], a web-based tool to promote depression screening and referral in social services agencies [87,88], to participation in county-wide planning to improve services under the California Mental Health Services Act [89]. These activities resulted in published evaluations, new agency relationships and programs, and funding of major initiatives, including a planning grant for centers of excellence for depression and substance abuse in South Los Angeles, and a new research initiative (Community Partners in Care or CPIC), designed to evaluate the effects on health outcomes of community engagement compared to more standard expert consultation to implement collaborative care for depression in under-served communities of color [88]. At the time of this writing, the CPIC initiative is implementing its intervention conditions in underserved communities in Los Angeles and has recruited nearly 100 community programs into a randomized trial.

These experiences provide a context from which to reflect on community engagement as an implementation strategy. The partnership has learned, for example, that community agencies already collaborate in addressing depression, based on experience, resources, and local and cultural histories. Community conceptions of depression often differ from the medical model and emphasize broader economic and social problems and histories of prejudice and racism. Owing to such factors, broad inclusion of diverse perspectives and active participation of stakeholders is necessary to achieve and sustain a community-based depression research initiative. Achieving such broad participation requires time to broker the fit of a rigorous implementation and evaluation of collaborative care to the realities and priorities of under-served communities, especially given the historical distrust of services and research in some communities.

This academic–community partnership has also found that the safety net of agencies serving vulnerable populations has many holes, and community members with depression often fall between gaps, because they are ineligible for programs based on income or residence requirements or categorical definitions of need. As a result, it can be difficult to implement all components of collaborative care, increasing the importance of understanding existing partnerships and “reweaving” the safety net to align agency resources with collaborative care requirements. Doing so, however, requires agency buy-in as well as building the partnerships and funding base — all important reasons to use a community engagement approach. More broadly, cultural competence and processes that respect and build on local agency histories and relationships are valued in underserved communities of color. Bringing in another top-down approach to “collaborative care” can be confusing or alienating, especially if familiar terminology (“collaboration”) is used in specific and unique ways that have meaning primarily in research and private sector circles. As a result of such factors, we suggest that, to implement collaborative care in underserved communities, local partnerships must work to align collaborative care goals with local histories and assets. Doing so may require an expanded language and set of implementation skills, based on community engagement.

To facilitate such approaches, the academic–community partnership has explored combining information technologies and community engagement strategies. For example, CPIC developed flash drives including toolkits for collaborative care for depression and distributed them freely at community engagement conferences that present both community-based and research-based approaches to collaboration. Such efforts are time consuming to formulate and implement. The planning phase for CPIC required 2 years, compared to 1 year for designing its predecessor Partners in Care, without extensive community engagement [90]. But community engagement may offer more complete and sustainable implementation of collaborative care for depression — an empirical question being explored in CPIC. In addition, community engagement may offer added value in terms of social justice outcomes, by promoting leadership of vulnerable populations in efforts to improve services available in their own communities and by reducing health outcome disparities for depression [91]. These potential gains are an important area for future research on community engagement and collaborative care.

4. Conclusion

Over 20 years of federal and foundation funding has created an extensive evidence base for collaborative care for depression and increasingly also other common mental disorders in primary care settings. Challenges now include local and federal collaboration on financing mechanisms to facilitate the implementation of such evidence-based approaches in diverse payment environments, and development of research to determine optimum ways to support and speed-up dissemination.

NIMH has recently funded new adaptations of collaborative care that are being tested in randomized trials in child and adolescent populations and in new settings such as obgyn, pediatric and community-based practices for under-served populations. Collaborative care interventions that can improve care for patients with natural clusters of chronic illness that are associated with adverse outcomes and high costs are also being tested in current trials. These trials have the potential of developing more cost-effective models of care for these complex and costly patients. NIMH has also funded community-based participatory research approaches that are being tried as a way to enhance academic and community partnerships to develop sustainable models of enhanced depression care. These community–academic partnerships have the potential to decrease disparities in care to underserved populations.

References

- 1.Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA. The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(6):685–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300027002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Somatization and psychiatric disorder in the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1494–500. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon W, Sullivan MD. Depression and chronic medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):3–11. [discussion 12-14] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):914–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):352–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katon W, Berg AO, Robins AJ, Risse S. Depression and medical utilization and somatization. West J Med. 1986;144(5):564–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research . Detection and Diagnosis. Vol. 1. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville (MD): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J. Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care. 1992;30(1):67–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Barlow W. Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15(6):399–408. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Druss BG. A review of HEDIS measures and performance for mental disorders. Manag Care. 2004;13(6 Suppl Depression):48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin EH, Katon WJ, Simon GE, et al. Low-intensity treatment of depression in primary care: is it problematic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(2):78–83. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grembowski DE, Martin D, Patrick DL, et al. Managed care, access to mental health specialists, and outcomes among primary care patients with depressive symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(4):258–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273(13):1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, McGuire T, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995–2005. Med Care. 2008;46(7):668–77. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katon W, Gonzales J. A review of randomized trials of psychiatric consultation-liaison studies in primary care. Psychosomatics. 1994;35(3):268–78. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(94)71775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. A randomized trial of psychiatric consultation with distressed high utilizers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(2):86–98. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valenstein M, Kales H, Mellow A, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis and intervention in older and younger patients in a primary care clinic: effect of a screening and diagnostic instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(12):1499–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katon WJ, Unutzer J. Pebbles in a pond: NIMH grants stimulate improvements in primary care treatment of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(3):185–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katon WJ, Seelig M. Population-based care of depression: team care approaches to improving outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):459–67. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318168efb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1042–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):706–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Norton K, et al. The Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) trial: design of a telecare management intervention for cancer-related symptoms and baseline characteristics of study participants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):240–53. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams LS, Kroenke K, Bakas T, et al. Care management of poststroke depression: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2007;38(3):998–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257319.14023.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2095–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Rutter CM. Incremental benefit and cost of telephone care management and telephone psychotherapy for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1081–9. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katon W, Unutzer J, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):265–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):65–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katon W, Russo J, Sherbourne C, et al. Incremental cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for panic disorder. Psychol Med. 2006;36(3):353–63. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katon WJ, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Cowley D. Cost-effectiveness and cost offset of a collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1098–104. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, et al. Long-term effects of a collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):741–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arean PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Med Care. 2005;43(4):381–90. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):613–30. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy-Byrne P, Sherbourne C, Miranda J, et al. Poverty and response to treatment among panic disorder patients in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1419–25. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Lee PJ. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with comorbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):224–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilmer TP, Walker C, Johnson ED, Philis-Tsimikas A, Unutzer J. Improving treatment of depression among Latinos with diabetes using project Dulce and IMPACT. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1324–6. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. [December 24, 2009];Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative. http://www.prhi.org/init_itpc.php.

- 42.Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) [July 28, 2009];Health Care Redesign. http://www.icsi.org/health_care_redesign_/diamond_35953.

- 43. [December 24, 2009];The MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care at Dartmouth and Duke. http://www.depression-primarycare.org.

- 44.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [December 24, 2009];Depression in Primary Care: Linking Clinical and System Strategies. http://www.lphi.org/dppc/.

- 45.The California Endowment [December 24, 2009];Integrated Behavioral Health Project (IBHP) http://ibhp.org/.

- 46.HOGG Foundation for Mental Health [July 28, 2009]; http://www.hogg.utexas.edu/programs_ihc.html.

- 47.John A, Hartford Foundation [July 27, 2009];IMPACT: evidence based depression care. http://impact-uw.org/.

- 48.Unutzer J, Powers D, Katon W, Langston C. From establishing an evidence-based practice to implementation in real-world settings: IMPACT as a case study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):1079–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Parker LE, et al. Impacts of evidence-based quality improvement on depression in primary care: a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1027–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubenstein LV. Review: collaborative care was effective for depression in primary care in the short and longer term. Evid Based Med. 2007;12(4):109. doi: 10.1136/ebm.12.4.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S58–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubenstein LZ, Alessi CA, Josephson KR, Trinidad Hoyl M, Harker JO, Pietruszka FM. A randomized trial of a screening, case finding, and referral system for older veterans in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):166–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rubenstein L, Chaney E, Smith J. Improving treatment for depression in primary care. QUERI Quarterly. 2004;6:1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oslin DW, Ross J, Sayers S, Murphy J, Kane V, Katz IR. Screening, assessment, and management of depression in VA primary care clinics. The Behavioral Health Laboratory. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans Health Administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith JL, Williams JW, Jr, Owen RR, Rubenstein LV, Chaney E. Developing a national dissemination plan for collaborative care for depression: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:59. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luck J, Hagigi F, Parker LE, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Kirchner JE. A social marketing approach to implementing evidence-based practice in VHA QUERI: the TIDES depression collaborative care model. Implement Sci. 2009;4:64. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grypma L, Haverkamp R, Little S, Unutzer J. Taking an evidence-based model of depression care from research to practice: making lemonade out of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Integration of Mental Health/Substance Abuse and Primary Care [December 24, 2009];AHRQ Evidence Reports. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=hserta&part=B151103.

- 61.Korsen N, Pietruszewski P. Translating evidence to practice: two stories from the field. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bachman J, Pincus HA, Houtsinger JK, Unutzer J. Funding mechanisms for depression care management: opportunities and challenges. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(4):278–88. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. [January 6, 2010];Partnerships for Solutions: Better Lives for People with Chronic Conditions. http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/partnership/index.html.

- 65.Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Improving quality of depression and medical care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAMcare Study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010 Mar 27; doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith SC, Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113(19):2363–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 1):S4–S41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, et al. Depression and diabetes: factors associated with major depression at 5-year follow-up. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):570–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2099–110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1242–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(1):133–44. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Visser S, Lesesne C. Mental health in the United States: prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder — United States, 2003. [October 26, 2009];MMWR Weekly. 1995 54(34):842–7. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5434a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richardson LP, DiGiuseppe D, Christakis DA, McCauley E, Katon W. Quality of care for Medicaid-covered youth treated with antidepressant therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):475–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gardner W, Kelleher KJ, Pajer K, Campo JV. Follow-up care of children identified with ADHD by primary care clinicians: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr. 2004;145(6):767–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scholle SH, Chang JC, Harman J, McNeil M. Trends in women's health services by type of physician seen: data from the 1985 and 1997–98 NAMCS. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12(4):165–77. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric–gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):759–69. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kelly R, Zatzick D, Anders T. The detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders and substance use among pregnant women cared for in obstetrics. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):213–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K. The vision, valley and victory of community engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4):S3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N, et al. Begin your partnership: the process of engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4):S8–S16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S18–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking Wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S67–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jones D, Franklin C, Butler BT, Williams P, Wells KB, Rodriguez MA. The Building Wellness project: a case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S54–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones L, Koegel P, Wells K. Bringing experimental design to community participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass/John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2008. pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stockdale S, Patel K, Gray R, Hill DA, Franklin C, Madyun N. Supporting wellness through policy and advocacy: a case history of a working group in a community partnership initiative to address depression. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S43–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Halpern J, Johnson MD, Miranda J, Wells KB. The partners in care approach to ethics outcomes in quality improvement programs for depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(5):532–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]