Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The performance of blind closed pleural biopsy (BCPB) in the study of pleural exudates is controversial.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the diagnostic yield of BCPB in clinical practice and its role in the study of pleural exudates.

METHODS:

Data were retrospectively collected on all patients who underwent BCPB performed between January 1999 and December 2011.

RESULTS:

A total of 658 BCPBs were performed on 575 patients. Pleural tissue was obtained in 590 (89.7%) of the biopsies. A malignant pleural effusion was found in 35% of patients. The cytology and the BCPB were positive in 69.2% and 59.2% of the patients, respectively. Of the patients with negative cytology, 21 had a positive BCPB (diagnostic improvement, 15%), which would have avoided one pleuroscopy for every seven BCPBs that were performed. Of the 113 patients with a tuberculous effusion, granulomas were observed in 87 and the Lowenstein culture was positive in an additional 17 (sensitivity 92%). The overall sensitivity was 33.9%, with a specificity and positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 71%. Complications were recorded in 14.4% of patients (pneumothorax 9.4%; chest pain 5.6%; vasovagal reaction, 4.1%; biopsy of another organ 0.5%).

CONCLUSIONS:

BCPB still has a significant role in the study of a pleural exudate. If an image-guided technique is unavailable, it seems reasonable to perform BCPB before resorting to a pleuroscopy. These results support BCPB as a relatively safe technique.

Keywords: Blind closed pleural biopsy, Malignant pleural effusion, Pleural exudates, Pleuroscopy, Tuberculous pleural effusion

Abstract

INTRODUCTION :

La biopsie pleurale fermée à l’aveugle (BPFA) est controversée pour étudier les épanchements pleuraux exsudatifs.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer le rendement diagnostique des BPFA en pratique clinique et leur rôle dans l’étude des épanchements pleuraux exsudatifs.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont fait une collecte rétrospective des données chez tous les patients qui avaient subi une BPFA entre janvier 1999 et décembre 2011.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 658 BPFA ont été exécutées auprès de 575 patients. On a obtenu des tissus pleuraux dans 590 (89,7 %) des biopsies. On a constaté une effusion pleurale maligne chez 35 % des patients. La cytologie et la BPFA étaient positives chez 69,2 % et 59,2 % des patients, respectivement. Chez les patients dont la cytologie était négative, 21 présentaient une BPFA positive (amélioration du diagnostic, 15 %) qui aurait évité une pleuroscopie dans les sept BPFA exécutées. Chez les 113 patients présentant une effusion tuberculeuse, on a observé un granulome dans 87 cas, et la culture de Lowenstein était positive dans 17 autres cas (sensibilité de 92 %). La sensibilité globale s’élevait à 33,9 %, selon une spécificité et une valeur prédictive positive de 100 %, et une valeur prédictive négative de 71 %. Les chercheurs ont constaté des complications chez 14,4 % des patients (pneumothorax 9,4 %; douleur thoracique 5,6 %; réaction vasovagale, 4,1 %; biopsie d’un autre organe, 0,5 %).

CONCLUSIONS :

La BPFA continue de jouer un rôle important dans l’étude des épanchements pleuraux exsudatifs. S’il est impossible de recourir à une technique orientée par imagerie, il semble raisonnable de procéder à la BPFA avant de procéder à une pleuroscopie. Les présents résultats étayent la relative innocuité de la BPFA.

The blind closed pleural biopsy (BCPB) has an important role in the study of pleural exudates according to guideline recommendations from different sources (1,2). It is an inexpensive, sensitive technique with few complications (3) and does not require great experience (4). Its major indication is the study of malignant and tuberculous effusions (5), the two most common causes of pleural exudate in Galicia, Spain (6), with a higher diagnostic yield in tuberculosis (7). There does not appear to be any difference in the diagnostic yield between different needles (Abrams or Cope) (8), and the optimum number of samples required to achieve an adequate diagnostic yield is well established (9). However, in the past few years, several studies have shown that if the pleural biopsy is guided by an imaging technique (ultrasound or computed tomography), its yield is even better (10,11). These data, along with the appearance of other diagnostic procedures, such as pleuroscopy (12), the superiority of pleural fluid cytology in the diagnosis of malignant effusions (13), the low prevalence of tuberculous effusions in developed countries (14) and that performing the procedure is not essential in young patients who live in areas with a high prevalence of tuberculosis (15), has led to questions regarding the use of this technique (16) and is currently the subject of controversy (17–20).

The aim of the present study was to determine the diagnostic yield of BCPB in clinical practice in our region, and to assess whether this technique still has a relevant role in the study of pleural exudates.

METHODS

Data were collected from all patients who underwent BCPB performed in the period between January 1, 1999 (the date when the histopathology department database was computerized) and December 31, 2011. The study was performed in a university general hospital in Galicia, located in the northwest of Spain, where the incidence of tuberculosis in 1996 (first year of available reliable data) was 72.3 per 100,000 inhabitants (21) and 28 per 100,000 (22) inhabitants in 2010, with an incidence of tuberculous pleural effusion (TBPE) in 2009 of 4.8 per 100,000 inhabitants (23). The protocol was evaluated and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Galicia (registry 2012/076) before commencement of the study.

The diagnostic algorithm used was that recommended by the Spanish Society of Chest Diseases and Thoracic Surgery (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica [SEPAR]) (2) with the difference that, depending on the clinical suspicion, the BCPB was occasionally performed at the same time as thoracocentesis, if pretest clinical suspicion was tuberculosis or malignancy, once an empyema or chylothorax was ruled out. The reason was the high prevalence of tuberculosis in the population and the low yield of pleural fluid in its diagnosis. Cases in which the pleural biopsy was performed using any imaging-guided technique were excluded. If the cytology and the BCPB were not diagnostic, the procedures subsequently performed to obtain a final diagnosis were reviewed (video-assisted thoracic surgery, fibrobronchoscopies, surgical biopsies, etc).

Pleural effusions were diagnosed as TBPE if: granulomas were found in pleural biopsy tissue samples; Ziehl-Neelsen stains or Lowenstein cultures of the effusion or biopsy tissue samples were positive; Ziehl-Neelsen stains or Lowenstein cultures of sputum samples were positive if the pleural effusion was accompanied by pulmonary infiltration; or patients <40 years of age with values of adenosine deaminase (ADA) >45 U/L and a percentage of lymphocytes >80% in the pleural fluid (15). Pleural fluid was considered to be a malignant pleural effusion (MPE) if the cytology or pleural biopsy was positive for malignancy. A paramalignant effusion was defined as a pleural effusion associated with a known malignancy and with no direct pleural involvement with the tumour when no other cause for the effusion could be found (24). The diagnoses of other pleural effusions were made according to previously defined criteria (2). The BCPB was performed, without distinction, with Cope (25) or Abrams (26) needles. At least four samples were sent to pathology and one to microbiology for culture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2). The follow-up period was at least one year after the diagnosis for all patients.

RESULTS

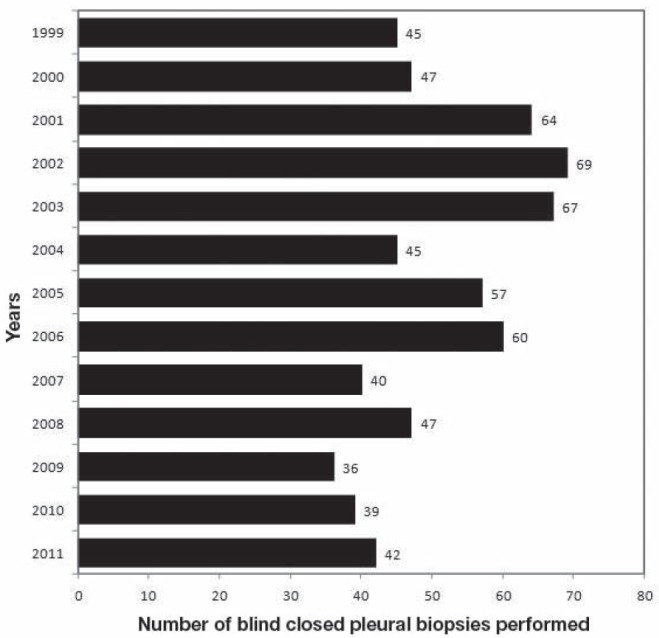

A total of 658 BCPBs performed in 575 patients were examined. Pleural tissue was not obtained in 68 patient samples (10.3%). A total of 83 patients underwent two biopsies, three patients underwent three and two underwent four. The biopsy was repeated if the pleural fluid and the previous biopsy had not been diagnostic, and the suspicion persisted that the effusion was of malignant or tuberculous origin. The characteristics of the patients studied are summarized in Table 1, and the numbers of BCPB/year performed over the study period are illustrated in Figure 1. The samples were examined by 14 different pathologists, but two (JA and IA) reported on 67.6% (n=453).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Effusion |

Age, years

|

Sex, M/F (% M) | Side of effusion (right/left/bilateral), % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | |||

| Malignant | 68.8±12.5 | 33–94 | 120/81 (59.7) | 106/65/30 (52.7/32.3/15) |

| Paramalignant | 70.1±11.2 | 37–90 | 50/26 (65.8) | 36/19/21 (47.4/25/27.6) |

| Tuberculous | 48.2±22.1 | 15–93 | 64/49 (56.6) | 61/52/0 (54/46/0) |

| Acute inflammatory pleuritis | 70±15.6 | 22–95 | 60/21 (74.1) | 45/36/0 (55.5/44.5/0) |

| Nonspecific chronic pleuritis/pleural fibrosis | 68.6±15.6 | 24–93 | 33/14 (70.2) | 24/18/5 (51/38.3/10.7) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0/2 | 1/1/0 (50/50/0) | ||

| No disease demonstrated | 69±16.8 | 28–91 | 43/12 (78.2) | 38/17/0 (69/31/0) |

| Total | 65±18 | 15–95 | 370/205 (64.3/35.7) | 311/208/56 (54.1/36.2/9.7) |

M Male; F Female

Figure 1).

Number of blind closed pleural biopsies performed according to year (n=658)

The final diagnoses of the patients studied are shown in Table 2, as well as the diagnostic yield of the BCPB for each diagnosis. Of the 575 patients included in the study, 201 had an MPE (35%). The cytology was positive in 139 patients (69.2%) and BCPB positive in 119 (59.2%). This technique diagnosed 21 patients with a negative cytology (diagnostic improvement 15%). The remaining 41 patients were diagnosed by performing video-assisted thoracic surgery (38 cases) and thoracotomy (three patients). Granulomas were observed in the BCPB in 77% (87 of 113) of the patients with a TBPE (19.7% of all patients) and, in an additional 17 (15%) in whom granulomas had not been observed, a positive Lowenstein culture was obtained in the biopsy (total sensitivity 92%). The other nine patients were <40 years of age, had a compatible clinical picture, and had an elevated ADA level and >80% lymphocytes in the pleural fluid.

TABLE 2.

Final diagnoses established in all patients (n=575) and diagnostic yield of pleural biopsies (n=658)

| Diagnosis | Biopsies, n | Patients, n |

Diagnosed, %

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCPB | Patients | |||

| Malignant | 225 | 201 | 119 (52.9) | 59.2 |

| Lung | 114 | 105 | 64 (56.1) | 61 |

| Non-small cell | 105 | 98 | 61 (58.1) | 62.2 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 79 | 79 | 48 (60.8) | 60.8 |

| Epidermoid | 18 | 14 | 9 (50) | 64.3 |

| Large cell | 8 | 5 | 4 (50) | 80 |

| Small cell | 9 | 7 | 3 (33.3) | 42.9 |

| Breast | 43 | 40 | 21 (48.8) | 52.5 |

| Lymphoma | 18 | 18 | 9 (50) | 50 |

| Stomach | 9 | 8 | 5 (55.5) | 62.5 |

| Kidney | 7 | 5 | 3 (42.9) | 60 |

| Pancreas | 6 | 4 | 3 (50) | 75 |

| Mesothelioma | 6 | 4 | 2 (33.3) | 50 |

| Others | 14 | 12 | 9 (64.3) | 75 |

| Unknown origin | 8 | 5 | 3 (37.5) | 60 |

| Paramalignant | 90 | 76 | ||

| Tuberculosis | 113 | 113 | 104 (92) | 92 |

| Acute inflammatory pleuritis | 86 | 81 | ||

| Nonspecific chronic pleuritis/pleural fibrosis | 67 | 47 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 | 2 | ||

| No disease demonstrated | 75 | 55 | ||

BCPB Blind closed pleural biopsy

The overall sensitivity of the BCPB was 33.9% if all the biopsies performed are taken into account. The specificity and positive predictive value for the diagnostic yield of MPE and TBPE was 100%. The probability of a case being neither tuberculosis nor pleural neoplasia (negative predictive value) when the pleural biopsy specimen was non-specific (taking into account the total of the procedures performed [n=658]) was 71%, although a negative result does not exclude these diagnoses.

There was no change in the diagnosis throughout the follow-up period. In the specific case of paramalignant effusions, 90 pleural fluid cytologies were performed in the follow-up year and none were positive.

A complication following BCPB was recorded in 95 (14.4%) of the procedures. A pneumothorax was documented in 62 (9.4%) and 12 (1.8%) required a chest drain. Intense chest pain following BCPB occurred in 37 (5.6%) procedures (34 with pneumothorax and three due to tearing of nerve fascicles in the biopsy). A vagal reaction occurred in 27 (4.1%) cases; in two cases, samples of lung were obtained and of the liver in another. No cases of hemorrhage, sepsis or death were reported.

DISCUSSION

When pleural fluid cytology is negative in a suspected case of MPE, there are several options for further investigations, including BCPB. However, in the past few years, several studies have shown that image-guided pleural biopsy and pleuroscopy have a higher yield in the diagnosis of MPE (10,12). The relatively low yield of BCPB is due to scarce, patchy and irregular distribution of the tumour invasion of the pleura, while the focal area of abnormal pleura can be biopsied with an image-guided cutting needle biopsy. With the emergence of pleuroscopy, the use of BCPB has declined significantly, especially in the developed world. Thus, some Western medical councils now no longer require competence in performing pleural biopsy by pulmonary and critical care specialists for their accreditation (27). While some authors consider the use of BCPB to be obsolete (28), others consider the decline in use to be a result of Western advancement (29) and vindicate its place in the study of a pleural exudate, particularly in countries were TBPEs are a problem and there is limited access to more expensive technologies (6). This is because, in these cases, BCPB has an increased diagnostic yield (7) similar to that of pleuroscopy (30) while there are no available data for image-guided pleural biopsy.

Our results suggest that BCPB is a technique that still has an important role in the study of pleural exudates. Thus, 59.2% of the MPE and 92% of the TBPE were diagnosed with this procedure, with an overall sensitivity of 33.9%. These results are similar to those obtained by Tomlinson (13) in a review of pleural biopsy yield from 2893 examinations performed between 1958 and 1985 (published in 14 articles), in which a diagnosis was obtained in 57% of the MPE and in 75% of the TBPE (13) (similar to ours, if we do not include the biopsy culture).

The diagnostic yield obtained in MPEs (59.2%) was in the range reported by other authors (Table 3). Mungall et al (31) obtained a sensitivity of 47% in MPEs (which would have reached 72% if the cases with a suggestive diagnosis were considered). Edmondstone et al (32) and McLean et al (33) reported slightly lower diagnostic sensitivities of 60% and 62%, respectively. On the other hand, in another four series, the sensitivity varied between 43.8% and 48.5% (3,10,34,35). These data are important is assessing the improvement in the diagnostic sensitivity of the cytology that BCPB provides, which was 15% in our series, and would have avoided one pleuroscopy for every seven BCPB that were performed – figures slightly lower than those obtained in a review on this topic (an improvement of 19.4%, and the need for 5.2 BCPB to avoid one pleuroscopy) (36). This improvement varies between 7% and 27% in the literature (37,38) for a similar cytology yield (71% and 72.6%, respectively). Lung cancer was the most common origin of MPE in our series (the majority [75%] being adenocarcinomas), followed by breast cancer and lymphoma, with a slightly higher diagnostic yield of BCPB in the former (61% versus 52.5% and 50%, respectively). Few mesotheliomas are diagnosed in our region (6) (four cases in the present series), likely due to the limited settlement of industry associated with asbestos in our area. The BCPB was diagnostic in 33.3% (six biopsies were needed to diagnose two cases), much lower than the 71.4% of Beauchamp et al (39) and higher than the 20.7% reported by Boutin et al (40).

TABLE 3.

Diagnostic yield of blind closed pleural biopsy in other series

| Author (reference), year | n |

n/n (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MPE | TBPE | ||

| Chakrabarti et al (3), 2006 | 75 | 21/46 (45.7) | 0/3 (0) |

| Maskell et al (10), 2003 | 25 | 8/17 (47) | 0/1 (0) |

| Mungall et al (31), 1980 | 55 | 17/36 (47) | 7/8 (88) |

| Edmondstone (32), 1990 | 28 | 12/20 (60) | No cases |

| McLean et al (33), 1998 | 24 | 10/16 (62.5) | No cases |

| Prakash and Reiman (34), 1985 | 414 | 123/281 (43.8) | 6/6 (100) |

| Bhattacharya et al (35), 2012 | 66 | 32/66 (48.5) | No cases |

| Nance et al (37), 1991 | 385 | 49/109 (45) | 35/71 (49) |

| Salyer et al (38), 1975 | 95 | 53/95 (55.8) | No cases |

| Present study, 2013 | 658 | 119/201 (59.2) | 104/113 (92) |

MPE Malignant pleural effusion; TBPE Tuberculous pleural effusion

The diagnostic sensitivity of BCPB in TBPE (92%) was similar to that reported in previous studies by our group (7) and by other authors (5). The remaining cases were diagnosed based on the observation of patients <40 years of age, with an ADA level >45 U/L and lymphocyte count >80% (19 cases) (15). Our usual practice is to attempt to confirm the diagnosis by performing a pleural biopsy because ADA level and the percentage of lymphocytes are markers that are not provided in the culture or yield information on whether resistance is present. In areas with a high incidence of tuberculosis and a low level of resistance, an elevated ADA level, along with a lymphocytic exudate, could establish the diagnosis. If there is also a high level of resistance, it is very risky to have confidence in the diagnosis and treatment based only on these markers. In these cases, it is recommended to perform a biopsy and culture, and determine drug susceptibility (41). The practical consequence of this elevated diagnostic sensitivity is that pleuroscopy will only be needed on few occasions to diagnose this pleuritis. In a review of nine series, mainly performed in Europe and the United States, the sensitivity of BCPB in TBPE was 54% (48 of 89), and was 7.6% of the total cases studied (89 of 1167) (3,10,31–35,37,38). It may be that tuberculosis was not a problem in the geographical areas where these studies were conducted, but this is not the situation in emerging and developing countries where tuberculosis is a major public health problem and the resources that they have to combat it are limited.

The overall sensitivity of BCPB in our series was 33.9%. However, it does appear that this is the best indicator to assess the diagnostic yield of this technique because the results will depend on, among other factors, the case mix of each series (better yield when more TBPE are included) or on the number of cases included with diagnoses other than MPE or TBPE. Thus, in our series, the fact of having performed a BCPB simultaneously in 81 patients who were subsequently diagnosed with acute inflammatory pleuritis has led to the overall yield of BCPB being lower. This is because it is sometimes difficult to differentiate these cases from TBPE. Thus, it seems more useful to assess its diagnostic sensitivity in accordance with the yield obtained in the diagnosis of a particular condition. No false-positive results with BCPB have been reported in any of the series, including ours, which shows that it is a highly specific technique.

Pleural tissue was not obtained in 68 of the 658 BCPBs (10.3%). This result is consistent with those obtained by other authors in which the ranges varied between 9% by Koegelenberg et al (11) and 29% in the series by Walshe et al (42) (performed by nonrespiratory teams). Other series obtained pleural tissue in 79% (3) and 90% (43) of cases.

The complications recorded were limited to pneumothorax (62 [9.4%] patients, of whom 12 [1.8%] required a chest drain), chest pain (34 [5.2%] patients who had pneumothorax and an additional three in whom nerve fascicles were obtained in the biopsy), a vasovagal reaction (27 patients [4.1%]) and obtaining a specimen of other organs (two from the lung and one from the liver). The complications reported after BCPB in other series are, in general, also low, and are limited to a pneumothorax (with the need of a chest drain in 1% of cases), pain or bruising at the puncture site, vasovagal reaction, biopsy of other organs and hemothorax (1,3,5,13,32,43), although in one series, two deaths were reported after experiencing a hemothorax (37).

The most important limitation of our study was its retrospective nature. The phase of the disease at the time of diagnosis was also not taken into account, which could have influenced the diagnostic yield of BCPB. This should be higher in advanced phases because it is more likely that the outer pleura are also affected, in addition to the visceral pleura. Many different chest physicians (staff members or residents) performed the BCPB throughout the study, and their experience with the procedure, which could influence the results, as well as complications, were not taken into account. It could also be argued that some of the effusions labelled as paramalignant were, in fact, an authentic MPE in which the diagnostic tests may have been negative. This appears to be highly unlikely because, at the time of diagnosis, all of them had mediastinal lymph nodes in the computed tomography scan that would lead to a blockage of lymphatic drainage and the subsequent pleural effusion. Besides, no malignancy was found in the 90 pleural fluid cytologies that were performed during the year of follow-up.

That the diagnostic yield of image-guided pleural biopsy is superior to BCPB is unquestionable, due to the information that it provides (size of effusion, presence of loculations, pleural nodes, etc), which helps in selecting the ideal puncture site and avoids potential complications. Although the present study was not designed to assess economic aspects, the costs of image-guided pleural biopsy and pleuroscopy (training of doctors, hospital stay, etc) are considerable and, for these reasons, have a significant impact in financial terms. We should consider whether all radiologists are trained to obtain image-guided pleural biopsies and if they would be available when needed. The sensitivity of BCPB in the diagnosis of MPE and TBPE in our series was sufficiently high to take these factors into account. This is of particular importance in areas with limited resources and difficulties with access to pleuroscopy or to imaging tests needed to guide the biopsy. On the other hand, it is likely that BCPB would be better tolerated than pleuroscopy because patients with an MPE are generally in a poorer state of health and, therefore, the risk associated with any type of surgery is also avoided. Furthermore, if pulmonologists abandon BCPB, new generations would not be familiar with this technique and those working in hospitals with limited resources will not be able to perform pleural biopsies and must transfer patients to tertiary hospitals to obtain a small pleural tissue sample.

SUMMARY

Our results suggest that BCPB still has an important role in the study of pleural exudates, particularly when malignancy or tuberculosis is suspected. In the diagnosis of an MPE, if an image-guided technique is not available, it seems reasonable, given its sensitivity, to perform a BCPB before resorting to a pleuroscopy because it helps to improve the diagnostic accuracy of cytology and avoids one pleuroscopy for every seven BCPB that are performed. Similarly, the high sensitivity obtained in the diagnosis of TBPE, a widely prevalent disease in developing countries, suggests that resorting to pleuroscopy would only be required in a few cases. The number of complications documented, and the low severity of these, supports it as a relatively safe technique. In the suspicion of an MPE, further studies will be needed to predict which patient phenotype is more likely to benefit from this examination.

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work was performed without funding.

DISCLOSURES: All authors have signed a conflict of interest form. There are no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Marco F Pereyra: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript. Esther San-José: Approval of the submitted and final versions, research design, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Lucía Ferreiro: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. Antonio Golpe: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. José Antúnez: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. Francisco-Javier González-Barcala: Approval of the submitted and final versions, research design, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting the manscript, critical revision of the manuscript. Ihab Abdulkader: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. José M Álvarez-Dobaño: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. Nuria Rodríguez-Núñez: Approval of the submitted and final versions, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. Luis Valdés: Approval of the submitted and final versions, research design, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting the manscript, critical revision of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maskell NA, Butland RJA, on behalf of the British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Group, a subgroup of the British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl II):ii8–ii17. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.suppl_2.ii8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villena-Garrido V, Ferrer-Sancho J, Hernández-Blasco L, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento del derrame pleural. Normativa SEPAR. Arch Bronconeumol. 2006;42:349–72. doi: 10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakrabarti B, Ryland I, Sheard J, Warburton C, Earis JE. The role of the Abrams percutaneous pleural biopsy in the investigation of exudative pleural effusions. Chest. 2006;129:1549–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D. Interventional pulmonary procedures: Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2003;123:1693–717. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escudero-Bueno C, García-Clemente M, Cuesta-Castro B, et al. Cytologic and bacteriologic analysis of fluid and pleural biopsy specimens with Cope’s needle: Study of 414 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1190–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.150.6.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdés L, Alvarez D, Valle JM, Pose A, San José E. The etiology of pleural effusions in an area with high incidence of tuberculosis. Chest. 1996;109:158–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valdés L, Álvarez D, San José E, et al. Tuberculous pleurisy: A study of 254 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2017–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.18.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouda AM, Dalati TA, Al-Shareef NS. A comparison between Cope and Abrams needle in the diagnosis of pleural effusion. Ann Thorac Med. 2006;1:12–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiménez D, Pérez Rodríguez E, Díaz G, Fogue L, Light RW. Determining the optimal number of specimens to obtain with needle biopsy of the pleura. Respir Med. 2002;96:14–7. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maskell NA, Gleeson FV, Davies RJO. Standard pleural biopsy versus CT-guided cutting-needle biopsy for diagnosis of malignant disease in pleural effusions: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1326–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koegelenberg CFN, Bolliger CT, Theron J, et al. Direct comparison of the diagnostic yield of ultrasound-assisted Abrams and Tru-Cut needle biopsies for pleural tuberculosis. Thorax. 2010;65:857–62. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.125146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michaud G, Berkowitz DM, Ernst A. Pleuroscopy for diagnosis and therapy for pleural effusions. Chest. 2010;138:1242–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlinson JR. Invasive procedures in the diagnosis of pleural disease. Semin Respir Med. 1987;9:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann MH, Nolan R, Petrini M, Lee YCG, Light RW, Schneider E. Pleural tuberculosis in the United States. Incidence and drug resistance. Chest. 2007;131:1125–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdés L, San José ME, Pose A, et al. Diagnosing tuberculous pleural effusion using clinical data and pleural fluid analysis. A study of patients less than 40 years-old in an area with a high incidence of tuberculosis. Respir Med. 2010;104:1211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emad A, Rezaian GR. Diagnostic value of closed percutaneous pleural biopsy vs pleuroscopy in suspected malignant pleural effusion or tuberculous pleuritis in a region with a high prevalence of tuberculosis: A comparative, age-dependent study. Respir Med. 1998;92:488–92. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann MH. Closed pleural biopsy. Not dead yet! Chest. 2006;129:1398–1400. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper C, Gary Lee YC, Maskell N. Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii4–ii17. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen JP. Why you do or do not need thoracoscopy. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:213–6. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00005410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koegelenberg CFN, Diacon AH. Pleural controversy: Closed needle pleural biopsy or thoracoscopy – which first? Respirology. 2011;16:738–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz-Ferro E, Fernández-Nogueira E. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Galicia, Spain, 1996–2005. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1073–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Informe da tuberculose en Galicia. Características dos casos de tuberculose de Galicia no ano 2010. Evolución do período 1996–2010 (publicación electrónica). <www.sergas.es/gal/DocumentacionTecnica/docs/SaudePublica/Tuberculose/Informe%20TB%202010_ampliado_galego.pdf> (Accessed January 12, 2013).

- 23.Valdés L, Ferreiro L, Cruz-Ferro E, et al. Recent epidemiological trends in tuberculous pleural effusion in Galicia, Spain. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:727–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahn SA. Pleural diseases related to metastatic malignancies. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1907–13. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10081907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cope C. New pleural biopsy needle. JAMA. 1958;167:1107–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.72990260005011a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abrams LD. New inventions: A pleural biopsy punch. Lancet. 1958;i:30–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)92521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stather DR, Jarand J, Silvestri GA, Tremblay A. An evaluation of procedural training in Canadian respirology fellowship programs: Program directors’ and fellows’ perspectives. Can Respir J. 2009;16:55–9. doi: 10.1155/2009/687895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvestri GA, Strange C. Rest in peace. The decline in training and use of the closed pleural biopsy. J Bronchol. 2005;12:131–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutt N, Aggarwal D. Closed needle pleural biopsy: A victim of western advancement? Lung India. 2011;28:322. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.85750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumann MH. Closed needle biopsy of the pleura is a valuable diagnostic procedure. Pro closed needle biopsy. J Bronchol. 1998;5:327–31. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mungall IP, Cowen PN, Cooke NT, Roach TC, Cooke NJ. Multiple pleural biopsy with the Abrams needle. Thorax. 1980;35:600–2. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.8.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edmondstone WM. Investigation of pleural effusion: Comparison between fibreoptic thoracoscopy, needle biopsy and cytology. Respir Med. 1990;84:23–6. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(08)80089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLean AN, Bicknell SR, McAlpine LG, Peacock AJ. Investigation of pleural effusion. An evaluation of the new Olympus LTF semiflexible thoracofiberscope and comparison with Abram’s needle biopsy. Chest. 1998;114:150–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prakash UB, Reiman HM. Comparison of needle biopsy with cytologic analysis for the evaluation of pleural effusion: Analysis of 414 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:158–64. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharya S, Bairagya TD, Das A, Mandal A, Das SK. Closed pleural biopsy is still useful in the evaluation of malignant pleural effusion. J Lab Physicians. 2012;4:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.98669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leddenkemper R. Thoracoscopy. State of the art. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:213–21. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11010213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nance KV, Shermer RW, Askin FB. Diagnostic efficacy of pleural biopsy as compared with that of pleural fluid examination. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salyer WR, Eggleston JC, Erozan YS. Efficacy of pleural needle biopsy and pleural fluid cytopathology in the diagnosis of malignant neoplasm involving the pleura. Chest. 1975;67:536–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.67.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beauchamp HD, Kundra NK, Aranson R, Chong F, MacDonnell KF. The role of closed pleural needle biopsy in the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma of the pleura. Chest. 1992;102:1110–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.4.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boutin C, Schlesser M, Frenay C, Astoul P. Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:972–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12040972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porcel JM. Pleural fluid biomarkers. Beyond the Light criteria. Clin Chest Med. 2013;34:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walshe AD, Douglas JG, Kerr KM, McKean ME, Godden DJ. An audit of the clinical investigation of pleural effusion. Thorax. 1992;47:734–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.9.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowie RL, Escreet BC, Goldstein BM, Langton ME, Leigh RA. Pleural biopsy. A report of 750 biopsies performed using Abrams’s pleural biopsy punch. S Afr Med J. 1983;64:92–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]